Abstract

Community-based adaptation (CBA) programs are now widely used in developing countries to address climate change impacts in vulnerable communities. There has been considerable growth in academic publications on CBA in peer-reviewed journals. There also exists a plethora of gray literature in the form of reports and evaluative studies prepared by government entities, international development agencies, and non-governmental organizations. This chapter presents a review of the current state of knowledge on CBA. We begin by summarizing a review paper that explores the conceptual clarity of CBA. We then highlight key trends and takeaways from a review paper on the evolution of CBA in academic literature. This is followed by a summary from another review paper on CBA initiatives documented in gray literature. We discuss the barriers and challenges to successful CBA observed in these papers. Finally, we present three case studies from the Philippines, Thailand, and Ethiopia as examples of CBA in practice beyond South Asia. These case studies illustrate the diversity of ways national and international organizations are working with local partners to implement community-based solutions for climate change adaptation across the Global South. The literature review and case studies offer important context and examples for the future development and evolution of CBA in the post-COVID-19 pandemic world.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keyword

- Community-based adaptation (CBA)

- CBA in academic and gray literature

- CBA barriers and CBA opportunities

- CBA case studies

-

Community-based climate change adaptation (CBA) programs are now widely used in developing countries to address climate change impacts in vulnerable communities.

-

Growth in academic and gray literature provides insights into the concepts, evolution, and barriers of CBA.

-

Case studies from the Philippines, Thailand, and Ethiopia illustrate the diversity of ways national and international organizations are working with local partners to implement community-based solutions in developing countries outside of South Asia.

-

Lessons from literature review and case studies offer opportunities for the development and evolution of CBA beyond 2020.

1 Introduction

Without necessary reflection on lessons learnt from the recent history of CBA academic literature, as well as more substantial lessons from similar areas of practice, including community-based natural resource management and participatory approaches to development, CBA initiatives risk continuing as isolated interventions, limited in both scale and impact. (McNamara & Buggy, 2017)

The term “community-based adaptation” or CBA was promoted by Huq and Reid (2007), but the principles associated with “community-based” or “bottom-up” approaches are not new in climate change discourse (Piggott-McKellar et al., 2019). A widely cited definition of CBA was articulated by Reid et al (2009) as “a community-led process, based on community’s priorities, needs, knowledge, and capacities, which should empower people to plan for and cope with the impacts of climate change.” Ayers and Forsyth (2009) provided further deconstruction of the concept by emphasizing the need for CBA to focus on vulnerability at the local level, identify ways to augment the adaptive capacity of communities, foster active engagement of local stakeholders and practitioners, integrate existing cultural norms, and address the root causes of vulnerability.

Early climate change adaptation (CCA) initiatives were dominated by “command and control” approaches that resulted in techno-centric, engineered, and infrastructure-type solutions (McNamara & Buggy, 2017). These initiatives were mostly driven by external entities—national or international—with limited direct engagement of the local community in the planning and decision-making process. Grassroots level initiatives—whether self-directed or externally facilitated—have become more widespread in the global south in the new millennium (Ayers & Forsyth, 2009; Schipper et al., 2014). There is increasing awareness that vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity are best understood at the local level—contextualized within exogenous macro-level factors.

We conduct a survey on CBA using literature review and case studies. First, we draw key observations from a review paper on the conceptual clarity of CBA. Second, we summarize the lessons learned from review studies of both scientific literature and gray literature. Third, we distill lessons and observations from selected papers on the barriers to developing effective CBA programs. Fourth, we present three case studies from the Philippines, Thailand, and Ethiopia. These examples situate the South Asian CBA initiatives highlighted in this book in the broader context of other developing countries of the Global South. Finally, we summarize the opportunities and pathways for CBA beyond 2020—during and in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis.

2 Core Properties of CBA

Kirkby, Williams, and Huq (2017) have conducted a comprehensive study to explore the conceptual clarity of CBA. They trace the origin of the usage of the term to the early 2000s and note that there is a lack of unified definition and understanding of the term. They draw from discourses in the literature and experiences from CBA in practice. Here, we present four key takeaways from their paper that provide insights into the core properties of CBA programs.

CBA is bottom-up, participatory, and place-based

CBA requires direct engagement of communities over the life cycle of the projects and by all relevant local stakeholders. Vulnerabilities are identified based on both scientific information and indigenous knowledge. It is a process that manifests in the sociopolitical landscape of the community where local people are involved through formal and voluntary arrangements and their participation is often institutionalized. There is an emphasis on training and capacity building at the grassroots level. Solutions to short-term crises are situated within the goal of developing long-term resilience. CBA initiatives build on a community’s strengths, indigenous knowledge, and local resources to maximize sustainable and resilient solutions (Shammin, Firoz, & Hasan, 2021, Chap. 2 of this volume).

CBA directly addresses the needs of the poor and the vulnerable

Top-down initiatives that dominated adaptation efforts globally were focused on hard infrastructure, resulting in bureaucratic and costly measures that failed to improve the long-term adaptive capacity of the poor and the vulnerable. On the other hand, CBA focuses on building local capacity, fostering community participation, integrating indigenous knowledge, prioritizing community empowerment, and investing in long-term well-being and resilience that can deliver adaptation solutions that are cost-efficient, representative, better managed, transparent, and effective as observed in the Shyamnagar experience (Amin and Shammin, 2021, Chap. 5 of this volume). It is a vulnerability-led approach which necessitates a broader recognition of both climate and other preexisting socioeconomic and ecological factors affecting poor and marginalized communities. Since these communities do not always have the resources to develop adaptation solutions autonomously, there is a need for extensive and transformative adaptation initiatives that directly target their needs.

CBA initiatives are multilateral, multi-level and cross-sectoral

CBA is a movement that involves financial, technical, and project development support from international agencies (e.g., the World Bank), global regimes (e.g., the Paris Agreement), the academic and research community, national and local governments, and international and local NGOs. In practice, CBA is often implemented as small-scale, localized, stand-alone, short-term, NGO-led projects that need to be scaled up, scaled out, and mainstreamed to be broadly effective. Grassroots engagement in disaster management in Bangladesh is an example of successful integration of community-level interventions into a national framework (Shammin, Haque, & Faisal, 2022, Chap. 16 of this volume). Even though people and organizations in the local communities remain the central focus in implementing CBAs, external involvement is still necessary to support the development of appropriate policies and frameworks for defining the rules of engagement. However, their role must be facilitative and supportive through decentralization and devolution of decision-making authority and administrative control. Finally, CBA programs cannot deliver sustainable and resilient solutions without cross-coordination with other related sectors. Climate change response interacts closely with initiatives for economic development, livelihood solutions, reduction of poverty and hunger, and the pursuits of justice and equality.

CBA has a growing community of practice

Unlike top-down adaptation programs, CBA relies on the experiences of a growing community of practitioners. Learning and sharing of successes, failures, best practices, and persistent challenges take place through publications, reports, conferences, workshops, and online forums. Since 2005, 14 international CBA conferences have been held through partnership of organizations such as CARE, International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), and other international and local organizations with the most recent iteration taking place online in September 2020 (IIED, n.d.). One of the most comprehensive online platforms for CBA knowledge sharing is weADAPT that allows practitioners, researchers, and policymakers to access credible, high-quality information and connect with one another (weADAPT, n.d.).

3 CBA in Academic Literature

Academic literature on CBA has evolved significantly in the past two decades with contributions from scholars across disciplines. In this section, we summarize selected findings of McNamara and Buggy (2017) who reviewed the evolution of academic literature on CBA starting from the early 2000s based on 128 publications identified through a systematic database search. They accomplished it through keyword search of the Scopus database starting with the broad topic of climate change adaptation and subsequently narrowing down to community-based studies in the social sciences.

CBA discourses during 2000–2010

In the early years, CBA literature recognized a trend away from top-down, technological approaches to community-based initiatives that build on local knowledge and resources. Communities have embedded natural resource management strategies and coping mechanisms for dealing with natural disasters that evolved over generations and can inform and strengthen adaptation efforts. There was increasing focus on deconstructing climate change impacts and responses at different scales leading to a better understanding of how climate vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity manifest at the local level. CBA offered a different paradigm for adaptation solutions that are grounded in the sociopolitical, economic, and ecological landscape of affected communities. This led to the exploration of cross-scalar approaches that bridge the separation between top-down and bottom-up initiatives. Local knowledge paired with scientific knowledge created opportunities for the development of integrated, multi-level solutions. There was growing emphasis on preexisting social drivers of vulnerability such as poverty, economic inequality, social injustice, and marginalization that exacerbate vulnerability and exposure to climate change impacts. Subsequently, ideas about conflating CBA initiatives with other development agendas such as poverty reduction, food security, and economic mobility emerged. Instead of reactive projects to address the impacts of climate change, CBA began to emerge as a pro-poor, pro-development project that advances the broader goals of sustainable development while increasing the resilience and adaptive capacity of communities.

CBA discourses beyond 2010

Since 2010, there has been significant growth in CBA literature on enabling factors including an emphasis on the use of participatory approaches to actively engage communities and facilitate the use of local knowledge over the life cycle of adaptation programs. What emerges from this are place-based initiatives that build on existing social and ecological capital and coordinate with existing efforts. These programs seek to ensure equitable and just solutions with local priorities and ownership as central to the process. The outcomes were community empowerment, enhanced adaptive capacity, and resilient solutions inspired by indigenous knowledge and grounded in local leadership. As a result, CBA was increasingly considered as a social process that manifests within the existing sociopolitical landscape of the community leading to a positive environment for collective problem-solving and decision-making. This laid the foundation for transformative structural changes that increased community resilience. Since risks and vulnerabilities were approached broadly to include a range of other preexisting development challenges, a more nuanced identification of vulnerability was possible. Increasingly, the social and economic inequalities faced by women and other marginalized groups were considered and made part of the solutions to climate vulnerabilities. The relationships between existing heterogeneity of communities and issues of power and governance were considered to reveal the root causes of climate vulnerabilities.

Institutions, communication, and finances for CBA

A large body of work is called for developing support for CBA across multiple scales to foster synergies between infrastructure and community-based solutions and strengthen the necessary institutions, policies, and rules of engagement. One key component of these multi-scalar interventions was ensuring mechanisms for effective communication and information sharing—from the upper echelons of the government or international agencies to the grassroots microcosm of the community. Social movements, advocacy, and the work of local NGOs made considerable progress in this regard to preserve the voice of the vulnerable population from being overshadowed by vested interests within and beyond the communities. Another key component was ensuring the availability of necessary funds by leveraging international financing sources. The Global Environment Facility, Green Climate Fund, United Nations Development Program (UNDP), and NGOs such as CARE International created grants and programs to stimulate the proliferation of CBAs across the developing world.

Critical discourses on CBA

In recent years, there have been a few critical discourses on CBA in academic literature. There is a need to upscale CBA from isolated, unique projects to a coordinated, standardized framework that can be replicated for it to be broadly effective. CBA needs to be mainstreamed to integrate local climate change adaptation concerns and development priorities into national development planning objectives. There are untapped opportunities for CBA initiatives to also address preexisting development issues in a community. There is a push to re-conceptualize CBA to become a flexible, learning process as part of a comprehensive toolbox of approaches for tackling climate change impacts and pursuing sustainable development. Mainstreaming CBA to address multi-scalar and multifaceted challenges will also require calibrating local initiatives with transformative action at the national, regional, and international scales. Finally, there is a need to develop monitoring and evaluation tools and outcomes to facilitate the learning process. For example, Bahinipati and Patnaik (2021, Chap. 4 of this volume) have found through a systematic literature review that there is a gap in farm-level adaptation research in India.

4 CBA in Gray Literature

Detailed information on the design, delivery, and experience of CBA often exists in the domain of gray literature. These include reports and evaluative studies by international development agencies, national and local governments, and non-government organizations. Since CBAs are often small scale, community driven and local, many initiatives do not get attention from scientific communities and hence are never scrutinized using scientific techniques. Many of these initiatives are reported and evaluated in the gray literature.

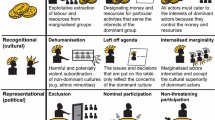

Piggott-McKellar et al. (2019) conducted an evaluative study on the barriers to successful CBA through a comprehensive review of gray literature available online and published in English between 2006 and 2016. They searched 21 Web sites from multilateral agencies and donors, 16 from CCA funding bodies, 71 from international NGOs, and 13 from research institutes and networks. The study found that the predominant issues addressed by these projects involved food security and agriculture followed by water security and coastal protection. Some projects also focused on broader issues such as conservation of natural resources, general livelihood solutions, and disaster risk reduction. The types of interventions used by these projects are summarized in Table 3.1.

There are a few challenges with gray literature on CBA. It is difficult to find publicly accessible online reports on CBA projects that offer detailed evaluation of outcomes and include adequate supplementary documents on project details. More comprehensive reporting and a systematic process of knowledge sharing would allow for useful learning experiences to be distilled from individual CBA projects across geographies and implementing agencies. The weADAPT platform mentioned earlier is a move in the right direction in this regard.

5 Barriers and Challenges to CBA

Piggott-McKellar et al. (2019) identified three overarching categories of barriers through their review of gray literature: sociopolitical, resource, and physical systems and processes. The sociopolitical barriers were divided into four thematic categories: (1) cognitive and behavioral (such as reluctance to adopt new technology or misalignment with cultural and religious values); (2) government structures and governance (such as poor resource and financing flows within the government); (3) communication and language (such as incompatible communication or unclear stakeholder roles and responsibilities); and (4) inequity, power, and marginalization (such as domination by the elite and powerful or gendered barriers for women). The resource-related barriers involved five categories: (1) financial (such as financial deficiencies or high implementation costs); (2) human resources (such as lack of oversight or high staff turnover); (3) time (such as limited time for relationship building, or long-term uncertainties); (4) access to information and technology (such as lack of access to information or communication hardware); and (5) infrastructural (such as poor quality of infrastructure or unintended consequences). Finally, the physical systems and processes constitute ongoing and potentially intensifying natural hazards induced by climate change that supersede the capacities of CBA interventions.Footnote 1

Kirkby, Williams, and Huq (2015) suggest that the aspirational goals of CBA to be inclusive, place-specific, and empowering, to support adaptation needs of the most vulnerable, are confronted with the following challenges:

-

Inadequate understanding of heterogeneity, internal differences, and uneven distribution of power in communities.

-

Difficulty in achieving meaningful participation of the poorest and the most marginalized.

-

Top-down perspectives embedded in the international scientific knowledge systems dominating local perspectives.

-

Excessive focus on the “local” downplaying important factors from outside the communities.

-

Insufficient and uncertain financing.

-

Lack of distinction between CBA and other development initiatives.

-

Inadequate integration of CBA into government policies and programs—sometimes due to corruption, political uncertainties, and lack of interagency coordination.

-

Deficiencies in the required technical expertise, funds, resources, and labor capacities to integrate CBA into government policies.

-

Improper sensitivity to local cultures inhibiting planned or autonomous adaptation.

McNamara and Buggy (2017) noted a few persistent questions regarding CBA that have been identified by scholars in the academic literature. While most CBA programs address local-level vulnerabilities of the present, they need to be transformed to be able to address long-term, unforeseen climate change scenarios. Unique local lessons need to be upscaled and mainstreamed for broader application. CBA needs to become multi-level and cross-sectoral to leverage greater long-term policy and financial support. CBA needs to adequately acknowledge and address the prevailing power dynamics and inequalities in communities. Short-term CBA goals need to be situated within longer-term projects and linked with other development priorities.

6 CBA in Practice

6.1 Urban Resilience in the Philippines

The World Risk Report 2018 ranks the Philippines as the nation at third-highest risk to climate change impacts worldwide (Kirch, 2018). In 2017, the country experienced 22 named typhoons and storms followed by 21 in 2018 as well as 21 in 2019 (PAGASA, n.d.). According to a recent IPCC report (IPCC, 2019), “Extreme El Niño and La Niña events are likely to occur more frequently with global warming and are likely to intensify existing impacts … even at relatively low levels of future global warming.” The urban poor in informal settlements is one of the groups most vulnerable to climate-related impacts, due in part to the additional pressures on urban systems created by rapidly increasing population growth (The World Bank, 2013). Figure 3.1 shows the progressively increasing occurrence of storms in the Philippines since 1900.

In September 2009, Typhoon Ketsana traversed aggressively through Metro Manila area, the national capital region and the most densely populated urban area of the Philippines with more than 12 million people living in its 636 square-kilometer land area near the coastline, causing unprecedented damages (GMMA READY Project Document, 2013). The typhoon caused more than 200 deaths and damaged more than 2 million homes in the Philippines (Scarano & Dunbar, 2009). The severity of impacts revealed the vulnerability of local systems and prompted Metro Manila to improve its disaster risk management. In addition to natural hazards, the vulnerability of the area is intensified by prevailing internal problems such as rapid urbanization and increased informal settlements (GMMA READY Project Document, 2013).

In 2009, Philippines passed the Climate Change Act that initiated the formulation of a National Framework Strategy on Climate Change which defined the overall parameters for the National Climate Change Action Plan (NCCAP)—the lead policy document guiding climate agenda at all levels of government from 2011 to 2028. The Climate Change Act and the NCCAP represent a clear evolution of priorities from mitigation to adaptation in the Philippines. The multi-agency READY project, a community-based adaptation program initiated before the Climate Change Act, was further expanded and integrated into emerging institutional frameworks. Supported by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and Government of Australia’s Australian Aid (AusAID), READY was implemented to target disaster risk management at the local level in 27 high-risk provinces in the Philippines. The project prioritized three main approaches (Sassa & Canuti, 2008): assessment of disaster/climate risk vulnerabilities; priority of local mitigation actions; and mainstreaming climate risk management (CRM) and disaster risk management (DRM) into local planning and regulatory processes.

In the aftermath of Ketsana, it made sense for the READY project to be implemented in the Greater Metro Manila Area (GMMA). The GMMA READY project conducted a risk-based vulnerability and adaptation (V&A) assessment of the GMMA based on short- and long-term climate scenarios to aid in the re-examination of land use (GMMA READY Project Document, 2013). Through analyzing multi-hazard maps, the project enabled local government units (LGUs) to re-examine land use development plans to determine the safest location of future public facilities and housing.

As part of local mitigation action to reduce climate risks, the GMMA READY project focused on educating and training local communities and established a community-based warning system. The early warning systems are neither cost-intensive nor highly sophisticated, functioning at the household level with simple and easily accessible instruments, such as rain gauges. Community members learn to install early warning systems, increase awareness, and allow LGUs to better implement priority mitigation measures. For example, pilot campaigns were implemented to perform drills and rapid assessments of the building structures under earthquake risk scenarios (GMMA READY Project Document, 2013).

Under mainstreaming CRM and DRM into local planning, software called Rapid Earthquake Damage Assessment System (REDAS) was developed to simulate and estimate the impacts of multiple hazards including earthquakes, floods, and tsunami. The REDAS was developed by Philippines Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) supported by local expertise and applied to the GMMA area. As an integrated risk assessment tool, REDAS allowed immediate mainstreaming of hazard data into resource planning. With free access and training, REDAS is used by 71 provinces, 30 state universities and colleges, private companies, and nonprofit and government institutions across the country (PHIVOLCS, 2018).

The READY project adopts a top-down approach to CBA. At the national level, the project institutionalizes and standardizes DRM measures, while at the local level, it prepares vulnerable communities in the Philippines to integrate DRM into their development plans (Agustin, 2016). However, community participation is the core accomplishment of this project. All three approaches used in the READY project are developed through pilot campaigns, public engagement, and leveraging local expertise. The READY project demonstrates a balance between local knowledge and technological innovation that offers a replicable model for other communities around the world.

6.2 Coastal Resilience in Thailand

Thailand, located in the southeastern region of Asia, has long coastlines mostly facing the Gulf of Thailand and partly exposed to the Andaman Sea and the Malacca Strait. The country has experienced changing temperatures and precipitation patterns for several decades. A period of recurrent and prolonged droughts between 2015 and 2016 led to critically low levels of water in reservoirs nationwide causing significant impact on agricultural productivity (Anuchitworawong, 2016). Thailand's susceptibility to extreme weather events such as tropical storms, floods, and drought makes it vulnerable to climate change. In addition to natural hazards, saltwater intrusion due to sea level rise is affecting rice fields, mangrove ecosystems, and coral reefs. Loss of ecosystem services from these natural resources and decline in fisheries across the coastal region of Thailand are endangering the livelihood of coastal communities. In recent decades, the local mean sea level has been increasing by 5 mm/year and can be attributed to land subsidence at the river mouth posing the impending threat of severe coastal recession in the Upper Gulf (Sojisuporn, 2013).

Recognizing the importance of indigenous knowledge in developing effective CBA programs, CARE Climate and Resilience Academy developed a Climate Vulnerability and Capacity Analysis (CVCA) method. This method facilitates the systematic collection of local knowledge on changes in living environments, resource scarcity in livelihood, local strategies against natural hazards, and past or even repetitive hazards. This is used to identify the most vulnerable resources and the critical institutions in the community, accessibility to essential services, and other key properties. The CVCA method was implemented in 20 coastal areas in Indonesia and 16 coastal areas in Thailand under the Building Coastal Resilience to Reduce Climate Change Impact in Thailand and Indonesia (BCR-CC) program. The BCR-CC program was a three-year project funded by the European Commission. This project focused on strengthening the capacity of coastal authorities and civil society organizations to deal with the challenges of climate change (Ketsomboon & Dellen, 2013). The BCR-CC project targeted four major categories in southern Thailand.

The first category was the promotion of climate-resilient livelihoods. Coastal communities in Thailand heavily rely on natural resources, such as fishing and agriculture, as their main source of income. Hence, it is necessary to provide resources and a knowledge-sharing platform for the local communities to understand the impact of climate change on their livelihoods. Climate data from national agencies should be converted into local languages and socioeconomic contexts to improve local community’s accessibility (Ketsomboon & Dellen, 2013). The process prioritized a bottom-up information flow since it can better address the specific needs and vulnerabilities of a community.

The second category was disaster risk reduction. Since mangrove forests play an important role in reducing the impacts of storms and floods in coastal areas, preventive measures were developed to protect the mangrove ecosystems. The measures included awareness of ecosystem services and restoration of degraded forest lands. The community in the village of Tambon Koh Klong Yang, one of the sixteen coastal areas, went through a series of educational programs about mangrove forests. This created incentives for the community members to safeguard the forests in an informed way. The restoration of mangrove forest in a deserted prawn farming location was initiated, and plans were put in place to expand the planting of additional mangrove forests (King, 2014).

The third category was capacity building for local civil society and government institutions. Prior to the intervention, the ministries on the provincial level in Thailand operated with a narrow focus on climate adaptation. This was most likely due to conflict of interest among different government agencies (Ketsomboon & Dellen, 2013). This created an institutional culture that resulted in inconsistencies and redundancies in adapting policies and programs. The BCR-CC program developed collaborative training on the big picture on climate change that educated people about the interconnectedness of climate adaptation initiatives with other development priorities. Climate and disaster-related information was put into context to make it accessible to local communities. Government agencies were encouraged to improve access to funding and opportunities for direct participation by community members.

The fourth category addressed the underlying causes of vulnerability. CBA programs often prioritize resource conservation and enforcement of laws and permits in the decision-making process. However, local communities who execute the national development strategies are most directly affected by the programs and outcomes. Their feedback, knowledge, questions, and concerns can better inform the national decision-making process. The BCR-CC project facilitated knowledge sharing by engaging community members in various stages of program development and implementation and integrating climate change education as part of those processes (Ketsomboon & Dellen, 2013). For example, in the village of Tambon Koh Klong Yang, students, community members, and tourists were engaged in planting mangroves during community events while learning about climate change in local communities. Moreover, a local regulation was drafted in a village meeting and shared with neighboring villages. The adopted regulation was written on a billboard, making it easily accessible to the community (King, 2014).

The BCR-CC project illustrates the links between ecosystem conservation and climate resilience. It also exemplifies the essential role of community working groups in knowledge sharing and implementing CBA programs.

6.3 Livelihood Resilience in Ethiopia

Ethiopia is a tropical landlocked country on the Horn of Africa. It is one of the most drought-prone countries in the world. Climate change has increased the incidence of drought due to rising temperatures, erratic rainfall, unpredictability of seasonal rain, and increased incidence of extreme events. The country also has high levels of food insecurity and ongoing conflicts over natural resources that exacerbate its vulnerability to climate change. These are projected to have significant impact on agriculture, livestock, water, and human health in Ethiopia (USAID, 2016).

The Graduation with Resilience to Achieve Sustainable Development (GRAD) project was designed to strengthen community resilience through livelihood solutions in Ethiopia. The focus was on building a system that facilitates financial management and loan access for poor households and engaging community members in analyzing key hazard maps. The main areas of focus of the GRAD project were to: enhance livelihood options, improve household and community resilience, and strengthen enabling environment to increase impact and sustainability. Between December 2011 and December 2016, the project helped build a more secure food network in 16 districts of Ethiopia through empowering women and developing sustainable farming practices.

GRAD was a USAID-funded project led and implemented by CARE, collaborating with local organizations. The essential tool established in the GRAD project is the Village Economic and Social Associations (VESAs) built on local traditions. VESAs provided community members, both men and women, with access to economic skills such as savings and credit, and financial literacy. Members of VESAs hold each other accountable to save money regularly. Those savings qualified them for small loans. According to a CARE report, 57,175 members had joined VESA by 2014 and 65% of VESA members have formal microfinance credit. Some other VESAs training sessions included good nutrition practices and climate change adaptations such as early maturing crop varieties and drought-tolerant crop types. By the end of the project, women made up 39% of the VESA participants (USAID, 2014).

GRAD prioritized livelihood solutions to climate-induced droughts. Although not related to the acronym, GRAD literally graduated participants from dependence on cash and food entitlements. It shifted the focus from aid and emergency assistance to building self-reliance and adaptive capacity—thus improving short-term well-being while building long-term resilience. Many of the GRAD interventions were designed to provide financial assistance to foster economic opportunities and enterprises. This was accomplished through provisioning of savings and credit, creation of production and marketing groups, and introduction of women-accessible economic activities. These economic interventions were accompanied by education initiatives on improving health and nutrition, gender relations, and harmful norms and practices.

GRAD instilled inner strength, ambition, and motivation among the participants. It promoted a culture of “aspiration” as opposed to “dependency.” “Before GRAD, I was alone in struggling for gender equality in my community,” and Kassa, a project participant, shared her experience with the GRAD project. Kassa started farming for her family when her father was getting old but did not receive much support from her family or the community because women did not traditionally work in the agricultural fields. GRAD triggered a shift in that tradition resulting in the engagement of both men and women to engage in and share household work and farming activities (CARE, 2016).

The GRAD project is an example of CBA initiatives delivering co-benefits of broader development challenges. In this case, co-benefits of building climate resilience were alternative livelihood opportunities, advancement in gender equality in the community, improved food security, development of community groups, and reduced dependency on external aid.

7 CBA Beyond 2020

At the time of writing this chapter, the entire world has been turned upside down by the COVID-19 pandemic. More than 85 million people worldwide have been known to be infected by December 31, 2020, with over 1.8 million confirmed deaths. The social order has been completely changed to combat this crisis—masks, social distancing, travel restrictions, and limits to the size of gatherings are among the most common measures taken globally. However, climate change impacts continue to take place in this transformed world and are making adaptation initiatives even more challenging. Developing community-engaged solutions is an intimate process. It involves staff from government departments, international agencies, and NGOs traveling to remote areas and interacting closely with many individuals and groups. Cyclone response involves directing people from vulnerable communities to congregate in the limited confines of cyclone shelters where any social distancing measure would reduce the capacity of the shelters to provide refuge. At least in the short run—assuming that this pandemic is a transient crisis—CBA initiatives are expected to face challenges that were not anticipated in the literature reviewed here. It does, however, pose the question of how future CBA programs can be designed to be resilient against unforeseen situations that may alter the social, political, or ecological order.

Building community resilience is at the heart of successful CBA. At the end of the day, vulnerable communities need to be able to withstand current and future threats of climate change—ideally on their own—and still be able to pursue their quest for improved well-being and a better quality of life. The literature review and case studies presented in this chapter illustrate that there have been exciting developments in the design, delivery, and outcomes of CBA initiatives in the last two decades. The importance of “community” in CBA has been established and fleshed out. For CBA to be successful, the community must be meaningfully engaged over the life cycle of the projects and local knowledge must be appropriately combined with scientific knowledge. Programs must be situated in the socioeconomic, cultural, and ecological realities of the communities including the nuances of preexisting inequities in power and privilege. This is true for programs administered by national or local governments and international agencies or NGOs—irrespective of whether the program is top-down, bottom-up, or some combination of the two. However, the extent and nature of community engagement may vary in these different circumstances. CBA initiatives also need to be multi-sectoral. The role of ecosystem conservation and natural resource management needs to be recognized and internalized through nature-based solutions. This is important because marginalized vulnerable populations are often disproportionately dependent on natural ecosystems for their survival.

Inclusive processes are likely to lead to building trust and ownership in the community which in turn would contribute toward long-term sustainability of the CBA solutions. The voice of the most vulnerable needs to be heard and meeting their needs should be the common denominator. There needs to be vertical and horizontal integration of institutions, information flows, and governance structures. The roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders need to be clearly defined. Improvements need to be made in documenting the details of CBA programs, instituting monitoring and evaluation processes, and sharing of lessons learned so that individual CBA initiatives can be upscaled and mainstreamed.

The GMMA READY, BCR-CC, and GRAD projects highlighted in this chapter illustrate a few of the myriad ways CBA programs are addressing some of these goals. Building on the successes of past initiatives and addressing the known barriers, CBA offers both immediate and lasting relief for climate-vulnerable communities in developing countries of the Global South. The scope of CBA solutions needs to be broadened to address other preexisting development issues as potential co-benefits. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) developed by the United Nations offer a well-established framework to integrate a broad range of social, economic, and ecological solutions with CBA initiatives. Shammin, Haque, & Faisal (2022, Chap. 2 of this volume) incorporates resilience principles and the SDGs into an integrated CBA framework for the development of climate-resilient communities. While the international community struggles to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to mitigate climate change, CBA solutions liberate people in these communities from relying on the mercy of developed countries who are responsible for the bulk of the emissions. CBA not only empowers vulnerable communities with climate resilience, but also provides them with the freedom of agency and hope for a better future—against all odds.

References

Agustin, N. (2016). GMMA READY Project terminal evaluation report. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Amin, R., & Shammin, M. R. (2021). A resilience framework for climate adaptation: the Shyamnagar experience. In A. K. E. Haque, P. Mukhopadhyay, M. Nepal, & M. R. Shammin (Eds.), Climate change and community resilience: Insights from South Asia. Singapore: Springer Nature.

Anuchitworawong, C. (2016). Analysis of water availability and water productivity in irrigated agriculture. Research Report. Thailand Development Research Institute Foundation.

Ayers, J., & T. Forsyth. (2009). Community-based adaptation to climate change. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 51(4), 22–31.

Bahinipati, C. S., & Patnaik, U. (2021). What motivates farm level adaptation in India? A systematic review. In A. K. E. Haque, P. Mukhopadhyay, M. Nepal, & M. R. Shammin (Eds.), Climate change and community resilience: Insights from South Asia. Singapore: Springer Nature.

CARE (2016). Aspire: Building resilience in the Ethiopian Highlands. CARE Ethiopia.

GMMA Ready Project Document. (2013). Philippines disaster and climate risks management. Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/dcrm-gmma-ready-project-pd.pdf. Last accessed September 17, 2020.

Huq, S., & Reid, H. (2007). Community-based adaptation: A vital approach to the threat climate change poses to the poor. International Institute for Environment and Development.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2019). Summary for policymakers. In H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N. Weyer (Eds.), IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. IPCC.

International Institute for Development Studies. (n.d.). https://www.iied.org/cba14-how-you-can-help-design-programme. Last accessed on August 14, 2020.

Ketsomboon, B., & Dellen, K. (2013). Climate vulnerability and capacity analysis report: building coastal resilience to reduce climate change impact in Thailand and Indonesia (BCR-CC). CARE Deutschland-Luxemburg E.V. and Raks Thai Foundation.

King, S. (2014). Community-based adaptation in practice: A global overview of CARE international’s practice of community-based adaptation (CBA) to climate change. CARE International.

Kirch, L. (Ed.) (2018). World Risk Report 2018. BündnisEntwicklungHilft and Ruhr University Bochum—Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV).

Kirkby, P., Williams, C., & Huq, S. (2015). A brief overview of Community-Based Adaptation. The International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD) at the Independent University, Bangladesh (IUB). Last accessed on July 29, 2019.

Kirkby, P., Williams, C., & Huq, S. (2017). Community-based adaptation (CBA): Adding conceptual clarity to the approach and establishing its principles and challenges. Climate and Development, 10(295), 1–13.

McNamara, K. E., & Buggy, L. (2017). Community-based climate change adaptation: A review of academic literature. Local Environment, 22(4), 443–460.

Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration. (n.d). Department of Science and Technology, Government of Philippines. http://bagong.pagasa.dost.gov.ph/. Last accessed September 12, 2020.

Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology. (2018). REDAS (Rapid Earthquake Damage Assessment System). Department of Science and Technology. https://www.phivolcs.dost.gov.ph/index.php/redas. Last accessed on September 20, 2020.

Piggott-McKellar, A. E., McNamara, K. E., Nunn, P. D., & Watson, J. E. M. (2019). What are the barriers to successful community-based climate change adaptation? A review of grey literature. Local Environment, 24(4), 374–390.

Reid, H., Alam, M., Berger, R., Cannon, T., Huq, S., & Milligan, A. (2009). Community-based adaptation to climate change: an overview. Special Edition on Community-Based Adaptation to Climate Change. Participatory Learning and Action. Nottingham: Russell Press.

Sassa, K., & Canuti, P. (2008). Landslides-disaster risk reduction. Springer.

Scarano, J., & Dunbar, B. (2009). NASA-Hurricane Season 2009: Typhoon Ketsana (Western Pacific). NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/hurricanes/archives/2009/h2009_Ketsana.html. Last accessed on September 20, 2020.

Schipper, E. L. F., Ayers, J., Reid, H., Huq, S., & Rahman, A. (Eds.). (2014). Community based adaptation to climate change: scaling it up. Routledge.

Shammin, M. R., Haque, A. K. E., & Faisal, I. M. (2022). A framework for climate resilient community-based adaptation. In A. K. E. Haque, P. Mukhopadhyay, M. Nepal, & M. R. Shammin (Eds.). Climate change and community resilience: Insights from South Asia. Singapore: Springer Nature.

Shammin, M. R., Firoz, R., & Hasan, R. (2021). Frameworks, stories and lessons from disaster management in Bangladesh. In A. K. E. Haque, P. Mukhopadhyay, M. Nepal, & M. R. Shammin (Eds.), Climate change and community resilience: Insights from South Asia. Singapore: Springer Nature

Sojisuporn, P., Sangmanee, C., & Wattayakorn, G. (2013). Recent estimate of sea-level rise in the Gulf of Thailand. Maejo International Journal of Science and Technology, 7(Special Issue), 106–113.

The World Bank. (2013). Getting a grip on climate change in the Philippines: overview (English). Washington, D.C.

United States Agency for International Aid. (2014). Graduation with resilience to achieve sustainable development (GRAD). https://www.careevaluations.org/wp-content/uploads/GRAD-MTE-Report-Vol-1-Main-Text-FINAL.pdf. Last accessed September 12, 2020.

United States Agency for International Development. (2016). Climate risk profile: Ethiopia. Climate links: A global knowledge portal for climate and development practitioners. USAID. https://www.climatelinks.org/resources/climate-change-risk-profile-ethiopia. Last accessed September 17, 2020.

weADAPT (n.d.). https://www.weadapt.org/. Last accessed on August 14, 2020.

Acknowledgements

Funding for student research assistants was supported by the Arthur M. Blank Fund through the Environmental Studies Program at Oberlin College. We thank Ramsha Babar and Leo Lasdun, student research assistants at Oberlin College, for assistance with literature review and data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Shammin, M.R., Wang, A., Sosland, M. (2022). A Survey of Community-Based Adaptation in Developing Countries. In: Haque, A.K.E., Mukhopadhyay, P., Nepal, M., Shammin, M.R. (eds) Climate Change and Community Resilience. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0680-9_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-0680-9_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-16-0679-3

Online ISBN: 978-981-16-0680-9

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)