Abstract

In Part III, titled “City Planning and New Technology,” we discuss two topics, namely, compact cities and real estate technology in Japan.

Promotion of compact cities is regarded as a high priority issue in urban policies in the era of population decrease. The Act on Special Measures concerning Urban Reconstruction in 2014 was revised to institutionalize the framework for the Location Normalization Plan, a plan for local governments to build compact cities to manage population decline and aging urban infrastructure while placing less burden on environment. Three chapters are devoted to issues related to this movement. In Chap. 18, Ishikawa (2020) discusses how urban functions can be guided by residents’ perspectives. To build a compact city, various day-to-day services must be placed proximal to residential areas; however, some services must be placed at a certain distance from residences because of land use restrictions. Therefore, we must determine the uses allowed in residential areas. In Chap. 19, Morimoto (2020) discusses the history of major contributions made by the development of transportation facilities to urban spread, the important role of traffic facilities to guide land use toward desirable purposes, and impact of self-driving vehicles on land use. In Chap. 20, Ogushi (2020) explains how the Location Normalization Plan in Niigata City was formed in detail.

Real estate technology refers to real estate business-related services that use new technology. Several new services based on new technology have been introduced in the field of real estate in Japan. Three chapters are devoted to issues related to real estate technology. In Chap. 21, Narimoto (2020) explains the outline of real estate technology services in Japan and identifies legal problems associated with handling of information. In Chap. 22, Nishio and Ito (2020) report on creating a sky view factor calculating system that uses Google Street View. Sky view factor is a term that refers to a configuration factor for the amount of sky in a hypothetical hemisphere. In Chap. 23, Kiyota (2020) explains the transition of neural network research and characteristics of deep learning and introduces a system that detects category inconsistencies in real estate property photographs submitted by real estate companies by using deep learning and a system that detects indexes associated with ease of living based on property photographs.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- City planning

- Compact city

- Location normalization plan

- Real estate technology

- Sky view factor

- Deep learning

1 Compact Cities

In Japan, as the population decreases, the urban land area required is also reducing; however, condensing urban areas that have already spread is difficult. Once constructed, buildings cannot be immediately demolished when no longer used. Vacant land and houses are not proximal to each other but are in a mosaic; thus, reduction of the surface area of urban areas is difficult (Asami, 2014). However, if the spread of urban areas is ignored and density decreases, urban administrative services will become inefficient and burden city finances.

The revision to the Act on Special Measures concerning Urban Reconstruction in 2014 considered these aforementioned concerns and led to the institutionalization of the framework for the Location Normalization Plan, a plan for local governments to build compact cities to manage population decline and aging urban infrastructure while placing less burden on environment (Asami and Nakagawa 2018). The Location Normalization Plan defines urban function development areas, which are urban centers and the base of day-to-day living to which urban functions (medical, welfare, and commercial) are guided to and consolidated in the future, and residential development areas, which are promoted as residential areas to maintain population density despite a declining trend in population and to sustainably secure day-to-day services and communities. The Location Normalization Plan further determines priority areas in modern urban areas where urban functions must be maintained in the future. Residential development areas are arranged around an urban function development area so that urban services can be used within walking distance. The Location Normalization Plan is designed to ensure that the use of the public transit system accommodates day-to-day transportation needs.

In Chap. 18, Ishikawa (2020) discusses how urban functions can be guided by residents’ perspectives. To build a compact city, various day-to-day services must be placed proximal to residential areas; however, some services must be placed at a certain distance from residences because of land use restrictions. Therefore, we must determine the uses allowed in residential areas. To do this, first, Ishikawa and Asami (2012) presented factors that explain the residents’ degree of satisfaction with residences, upon which, based on Ishikawa and Asami (2013a), discussions were introduced in relation to what kind of mixed use is acceptable in areas of residence. The result showed that essential services are well accepted, but mixing residential areas with unpleasant services tended not to be tolerated. In addition, based on Ishikawa and Asami (2013b), the relationship between the degree of satisfaction with convenience and allowances of mixed usages was shown, that is, residents dissatisfied with long distances to essential services may still not want these services near their homes.

In Chap. 19, upon reviewing the history of major contributions made by the development of transportation facilities to urban spread, Morimoto (2020) asserts that transportation has been improved to accommodate increases in traffic demand, which is a derived demand from land use. Based on this, Morimoto argues that because traffic demand decreases with declines in population, the use of traffic facilities (i.e., existing stock) is critical to appropriately guide land use toward desirable purposes. Morimoto suggests a next-generation streetcar system (Light Rail Transit: LRT) as a next-generation public transit system, which is being introduced to city development globally. In Japan, this system was introduced only in Toyama City, and Utsunomiya is a candidate city, which Morimoto describes in detail. Morimoto further discusses self-driving vehicles as a next-generation transit method with an impact on land use. Morimoto also argues that the formation of a transit transfer station between the trunk lines and feeder lines is a key aspect of creating a compact city.

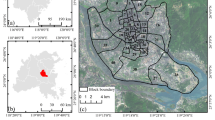

In Chap. 20, Ogushi (2020) explains the formulation of the Location Normalization Plan in regional cities, looking at the case of Niigata City. In 2007, the government merged 14 municipalities to create Niigata City. Seventy percent of Niigata residents use personal vehicles for transportation; thus, their dependence on automobiles is high. In 2015, the Bus Rapid Transit, which travels on trunk roads, was introduced as a public–private partnership, and surplus drivers and buses were assigned to the areas with limited transit services in an effort to improve access within the city. Ogushi describes how, at a roundtable conference on sustainable city planning that examined the Location Normalization Plan, it was emphasized that the allocation of development areas is intended to loosely implement appropriate land use and is not mandatory. Specifically, public transit improvement garnered increasing interest, and many opinions were expressed. Ogushi highlights how because each of the 14 municipalities that had been merged originally had a different background, there were strong arguments for the uniqueness of each municipality. Thus, holding a discussion on optimizing overall land use through strategic investment in specific areas was difficult.

2 Real Estate Technology

Real estate technology refers to real estate business-related services that use new technology. New services, which utilize information technology, such as systems with advanced search function, systems that match providers and consumers, systems that evaluate property values, and systems that allow for online viewing via virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality, have been and are being developed as businesses.

Real estate technology has revitalized and improved the real estate business and also has the potential to fundamentally transform the industry moving forward. However, the legal system for real estate is based on traditional business styles and does not address developments in real estate technology. Thus, beyond simply technology, reform of the legal system is also required.

In Chap. 21, Narimoto (2020) explains the outline of real estate technology services in Japan and identifies legal problems associated with handling of information. The types of real estate technology services are as follows:

Matching platform services for rental, purchase, and development: These match providers and customers online, and their status as an agency based on the Real Estate Brokerage Act is ambiguous. Simple provision of information and communication of intents are not interpreted as agency. From 2017, computerization of disclosure statements (i.e., when buying and selling real estate, if a residential real estate contractor mediates by explaining important matters about the contract to the consumer, the contractor must explain these matters to the consumer) was introduced in rental agreements, but paper documents remain to be a requirement.

Property value evaluation and information retrieval services: These estimate property values by introducing information technology such as artificial intelligence. However, when financially compensated, this service could be considered property appraisal.

Crowdfunding: A system that collects funds by connecting companies and investors online. It is worth noting relationship of this system to the Act on Specified Joint Real Estate Ventures, Financial Instruments and Exchange Act, and the Act on Prevention of Transfer of Criminal Proceeds.

Data analysis services: These include store analysis provided by images captured by cameras in stores.

Business efficiency services: These support the real estate industry by improving the efficiency of information technology.

VR technology: It is a service that presents completed images by using VR technology.

Narimoto identifies information technology as essential in real estate technology but stresses that caution is necessary regarding the protection of personal information, protection of privacy, and legality of crawling.

In Chap. 22, Nishio and Ito (2020) report on creating a sky view factor calculating system that uses Google Street View. Sky view factor is a term that refers to a configuration factor for the amount of sky in a hypothetical hemisphere. With the revision to the Building Standards Act in 2003, a regulation on sky view factor was introduced to provide relaxation to setback regulations (wherein a diagonal line is drawn inside a property at a constant angle from a certain height at the border, and construction is only allowed below the line). Basically, this regulation makes building super high-rise buildings easier but can be applied to the relaxation of the setback regulation for the road in low-rise systems. The method proposed by Nishio and Ito obtains longitude and latitude from Google Street View and calculates sky view factor through image processing. In addition, the sky view factor calculation system is used to calculate sky view factors in areas with different land use, road width, and distance from stations, and trends are reported. Although Google Street View is not a system for measuring sky view factor, it is a good example of obtaining new information provided by image processing.

In Chap. 23, Kiyota (2020) explains the transition of neural network research and characteristics of deep learning and introduces a system that detects category inconsistencies in real estate property photographs submitted by real estate companies by using deep learning and a system that detects indexes associated with ease of living based on property photographs. Kiyota provides massive datasets that include property photographs and layouts free of charge for academic purposes and reports that new research is underway.

References

Asami Y (ed) (2014) Reflecting on vacant land and vacant house in cities. Progres, Tokyo

Asami Y, Nakagawa M (eds) (2018) Reflecting on compact cities. Progres, Tokyo

Ishikawa T (2020) “Guidance of urban facilities and functions in compact mixed-use development from the perspective of residents: Residents’ perceptions of mixed land use and performance-based regulation” in this book

Ishikawa T, Asami Y (2012) Perception of the quality of urban living and residential satisfaction: in relation to residential characteristics, human values, and physical environments. J City Plan Inst Jpn 47(3):811–816

Ishikawa T, Asami Y (2013a) Urban residents’ perception of land-use and dimensional regulations: effects of reducing unpleasant factors and the possibility of performance-based regulation. Journal of the City Institute of Japan 48(1):1–8

Ishikawa T, Asami Y (2013b) Residents’ psychological evaluation of mixed land use in residential areas. J City Plan Inst Jpn 48(3):909–914

Kiyota Y (2020) “Frontiers of computer vision technologies on real estate property photographs and floorplans” in this book

Morimoto A (2020) “Advanced transport systems and compact cities: Compact city corresponding to the advanced transport systems” in this book

Narimoto H (2020) “The overview and legal issues regarding real estate tech” in this book

Nishio S, Ito F (2020) “Proposal of system for calculating sky view factor using Google Street View” in this book

Ogushi Y (2020) “Current status and issues for urban (regional area) formulation of the location normalization plan: The case of Niigata City” in this book

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Asami, Y. (2021). Introduction: City Planning and New Technology. In: Asami, Y., Higano, Y., Fukui, H. (eds) Frontiers of Real Estate Science in Japan. New Frontiers in Regional Science: Asian Perspectives, vol 29. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8848-8_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8848-8_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-8847-1

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-8848-8

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)