Abstract

This chapter explores emerging findings from the research question, “What characterizes a successful transition of a school from traditional classrooms to an innovative learning environment in the context of the design and construction process?” Many schools today are trading in their identical classroom model for activity-driven, technology-infused spaces and envision a future in which teaching, culture, and space align seamlessly resulting in the intangible “buzz” of engaged learning. However, research and experience show many of these schools fail to supplement the design and construction process with initiatives to align teaching practices, organizational structures, and leadership with the intended vision. This often results in a misalignment between the pedagogical goals of the building and its subsequent use. To provide a research-based course of action for transitioning schools and a basis for future Ph.D. study, exploratory case studies were completed of schools operating in new buildings and having achieved this “buzz”. Emerging best-practice processes and tools are shared.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alignment of School Design and Use

When categorizing spaces by the alignment of pedagogy and design intent, four scenarios emerge (Fig. 1). One represents the “status quo” in which teachers teach with predominantly direct instruction in a school with a traditional design (for example, double-loaded corridor, identical classrooms, rows of desks facing a teaching wall). The reverse of this is what this chapter deems “the buzz” in which teaching is predominantly student-led and multi-modal in a school with an innovative learning environment design, or ILE (defined as being multi-modal, activity-based, and technology-infused). There is also the “square peg, round hole” scenario in which there is student-led teaching and learning occurring in a traditional space and the “wasted investment” scenario in which there is an ILE design but still predominantly teacher-led, direct instruction.

Many schools end up in this “wasted investment” quadrant when they invest in new spaces but do not invest in developing new teaching and organizational practices (Saltmarsh, Chapman, Campbell, & Drew, 2015). Through case studies answering the question, “What characterizes a successful transition of a school from traditional classrooms to an innovative learning environment in the context of the design and construction process?” this research seeks to identify strategies to help schools and teachers transition from the “status quo” to “the buzz” while avoiding “wasted investment”.

Literature Review

When considering the transition into new spaces, the literature often focuses on the design with little regard for the “implementation and transition phase” (Blackmore, Bateman, O’Mara, & O’Loughlin, 2011). Blackmore et al. (2011) identified seven areas requiring further inquiry, three of which will be addressed through the Ph.D. research of which this chapter is the first step: “the processes and preparation required to transition…the types of practices that emerge in new spaces…(and) the organisational cultures and leadership that facilitate or impede innovative pedagogies” (Blackmore et al., 2011, p. v). Teaching and learning often remain traditional and explicit despite inhabiting new space types with broader teaching and learning potential (Saltmarsh et al., 2015). This is anticipated to be due to lack of focus on organizational structures, leadership, relationships, and/or teacher professional development. Previous research completed on school design often ignores these factors while literature on whole school change often ignores the impacts of school design.

It is important to note that this research does not focus on the design of space itself nor its impact on teaching and learning. Research here is well covered and ongoing (Barrett, Davies, Zhang, & Barrett, 2015; Blackmore et al. 2011; Cleveland & Fisher, 2014; HEFCE, 2006). Instead, this chapter operates under the assumption that the design team has created a space that, if used as intended, has the potential to function properly in regard to pedagogy, acoustics, technology, air quality, and lighting, among others. The focus instead is on the transition process implemented to shift the school organization and support educators to align their practices with the intended functions of the new space.

Research Design

The research question, “What characterizes a successful transition of a school from traditional classrooms to an innovative learning environment in the context of the design and construction process?” aligns with Yin’s (2014) scope of a case study in that the phenomenon of school transitions is a contemporary, real-world phenomenon highly impacted by its organizational, social, and political contexts. Further, the features of a case study apply in that multiple variables (rather, the characteristics of the transition) overlap and thus, multiple sources of evidence connected through theoretical basis are required to properly triangulate data and come to valid conclusions. The research process was both reflective with examination of the previous design and transition process and real-time with examination of the ongoing transitional efforts being made in the early years of occupying the school.

The unit of analysis is the entire school or in the case in which only part of the school was redesigned, the portion of the school residing in new space. The teachers are an embedded unit of analysis. The transition process includes, but is not limited to, the following elements: leadership; professional development; educator perceptions; presence and type of students; teacher, stakeholder, and community engagement; and, strategic messaging. The initial bounds were fluid due to the exploratory nature of the case studies.

Site Selection

To successfully answer the research question, participating schools must have (1) a newFootnote 1 ILE design; (2) been initially staffed with teachers used to teaching in traditional settings; (3) an indication that it is operating as intended or on track to do so (rather, on track to achieve “the buzz”); and (4) the ability to provide access to documentation of the design and transition process. For the research and analysis to remain feasible within the ten-month timeline of the Fulbright scholarship program, case study sites were limited to four. Case study sites were selected by applying these requirements to data collected through a survey conducted by the Innovative Learning Environments and Teacher Change (ILETC) research project led by the Learning Environments Applied Research Network from The University of Melbourne (Imms, Mahat, Byers, & Murphy, 2017). The main research question of the ILETC is “Can altering teacher mind frames unlock the potential of innovative learning environments?” (ILETC, 2016). A central component of this research is the relationship between types of learning environments, teaching practices, teacher mind frames, and student deep learning (Imms et al., 2017).

The ILETC survey was completed by 822 school principals and/or leaders throughout Australia and New Zealand. The survey classified the school’s physical environment design and measured its teacher mind frames, the presence of student deep learning, and teaching approaches, among other items (Imms et al., 2017). ILE design was determined by respondents indicating a learning space type of C, D, or EFootnote 2 from Dovey and Fisher’s spatial typologies (2014). Case studies with likely successful operations were identified as those scored with above-average ratings for teacher mind frames and student deep learning and having a predominantly student-centred teaching approach. An internet search on schools fitting the criteria was completed to rule out schools not residing in new facilities. A subsequent telephone census was conducted with schools passing the internet search to identify if teachers had come from traditional settings, that documentation of the design and transition process was feasible, and confirm willingness to participate as a case study site. Schools were approached for participation in descending order of their teacher mind frame scores.

The first four schools that passed the telephone census and expressed willingness to participate were selected for case studies, one of which contained multiple, separate ILE sites. Two of the schools were located in Australia and two in New Zealand. One was a Catholic school and the others were government schools. They support communities of varying levels of socio-economic backgrounds and were all at different points of their transition with some more established than others. Some were brand new schools to support population growth and others replaced existing facilities. Regardless, all schools were trying to take teachers from traditional teaching in traditional facilities to successfully inhabit an innovative learning environment.

Methods

Participants from each case study site included teachers, school leaders, and school designers. A total of 20 teachers, 4 school leaders, and 3 designers have participated in the study. Teachers participated in a focus group consisting of a transition game, the creation of a Journey Map, and completion of a letter written to a future teacher transitioning to an ILE. This focus group format was developed through workshops as part of the ILETC and tested through a pilot study at a school in Victoria, Australia. Images of these tools can be found in Figs. 2 and 3. Teachers also participated in a one-on-one interview following the focus group. School leaders participated in an interview and led a tour of the school. School designers, which encompass architects and/or educational planners or members of the establishment board, participated in an interview.

This chapter represents initial thematic analysis from the interviews and focus groups. Interviews and focus groups were transcribed by the researcher and inputted into Nvivo qualitative analysis software. A grounded theory approach was taken. The first step involved the assignment of one or more codes to each data point in the transcripts. These codes evolved from the data and were not pre-determined. As new codes were created throughout the process, the second round of coding was completed to ensure that all transcripts benefited from the full set of codes. These codes were then aggregated into broader themes and finally organized into the three broad categories, discussed later in this paper. Figure 4 indicates one example of the coding process followed by the researcher, using the example of Organizational Enablers. Indicative quotes are provided along with initial codes and their alignment to the final themes. It is anticipated that further theoretical sampling will be undertaken along with follow-up interviews and supplemental data collection.

Defining the “Buzz”

Defining success is not a goal of this research. Instead, this research sought to understand the alignment between what the school wished to see as success and the subsequent reality of the space and its use. Thus, one of the questions asked of all research participants at the four selected case study sites was how they personally define success in their new spaces. Deduced from the data was the concept of “the buzz” or rather, the palpable presence of student-driven, engaged learning. The following interview quotes are indicative of the conversation at all four schools around the definition of success in an ILE.

…it’s the start of the unit where they’re going off and doing a bit of searching about something they’re interested in—there’s a real buzz in the room and I think that’s a sign of success

The measure of success is in how it “just works”. Sometimes it’s not tangible. But the place is always alive and buzzing…I see a really cohesive group of people working together for the benefit of the students and that’s, that is tangible.

It’s like an idling engine so it kinda just hums along and (teachers) don’t have to be there for it to go like that but when (they) want it to accelerate then that’s where (teachers) come in.

(success is) that one on one individual, moving around…it’s the hum of learning together and discussing and you think, where’s the teacher?!

The “buzz” is not a prescriptive term, yet it elicits clear understanding regarding what expectations and activities underlie the word. It also lends itself as being broad enough to encompass an array of pedagogical goals of a school. Many things can result in the “buzz”; it is not created through the building itself but in the inhabitation of the facility and its corresponding culture, leadership, organizational structures, and teacher mindsets that coincide.

Emerging Themes

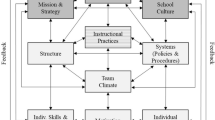

This paper reflects findings from early stages of analysis of exploratory case studies. At the moment, themes are aligning into three categories: pre-occupation enablers which are steps schools took before moving into their new facilities, organizational enablers which represent the ongoing cultural, leadership, and structural variables, and spatial enablers which are moments in which the spatial design itself plays a key role in helping teachers and students shift their practice. It should be noted that there are few clean breaks between themes. They interrelate with one another as the pre-occupation steps help set the stage for the culture to take hold or the space to have the leverage required. Further, their effectiveness depends on many moderating factors. Unpacking this process will occur through future Ph.D. research.

Pre-occupation Enablers included prototyping space and pedagogy, forming clarity around the purpose of the spatial design, and indoctrinating the “why” of the design through research. Organizational Enablers included establishing and embedding a shared language; focusing on relationships between teachers, between teachers and students, and between students themselves; maintaining a culture of risk; and purposeful structure across each level of the organization. The latter is what this chapter is calling “layered scaffolding” and is explored in more detail below. Spatial enablers included transparency and openness allowing for visible teaching, ongoing authentic observation, and implicit student behaviour management. The sense that spatial inflexibility could ‘nudge’ a teacher to shift pedagogically also arose from the data. Figure 4 uses the example of Organizational Enablers to provide indicative quotes and show initial codes and their alignment with the eventual themes.

An Example Strategy: Layered Scaffolding

All case study sites utilized an ongoing process this chapter calls “Layered Scaffolding”. This is the notion of providing the ideal amount of structure at each layer of the organization so that the level below experiences “just enough” guidance to allow innovation to flourish. The government level, which may be the Department/Ministry of Education or the establishment board, provided structure over which the principal was appointed and mandated to innovate. This may be the school design itself and/or a prescribed pedagogical direction, among other possibilities. The principal and other school leaders establish timetables, evaluation metrics, or other non-negotiables that align with this vision and provide a basis through which educators can have autonomy over their courses. These educators then establish routines for students or leverage purposeful relationships to guide student behaviour and allow appropriate amount of choice and self-regulation in their learning. One school leader interviewed summed this concept up well by saying “If you want the freedom at the student level then you need to be super structured up top”.

In schools or learning spaces in which such scaffolding was not done, or structure was not provided, teachers created their own which would trend towards the traditional. This concept aligns with other recent work on structuration in which teachers, when perceiving a lack of order, imposed their own inflexible spatial practices and didn’t make best use of either the space or materials. “Teachers see the imposition of (their own) additional structuring of both lessons and the daily timetable as the most appropriate pedagogic response to what they perceive as a lack of order” (Saltmarsh, et al., 2015, p. 322).

One example of such “layered scaffolding” is a strategy employed by one of the schools to assist teachers in modifying their pedagogy. This principal, when preparing teachers to inhabit a school with a prescribed vision of team teaching and spaces with flexible, non-traditional furniture developed a series of expectations for educators through the language of David Thornburg’s archetypes (Thornburg, 2001, revised 2007). These archetypes compare learning spaces to campfires, watering holes, caves, and the like and provide a shared language for space. The archetypes were then used as part of educators’ cultural and spatial induction. They were incorporated into teachers’ lesson planning, ongoing classroom management, and teachers’ own evaluation. With the expectation of their students sharing this language as well, some teachers created tangible icons, manipulatives, and displays. The discussions of space were thus ingrained in the daily operations and routines and became effective proxies for the envisioned pedagogy and student behaviour. For example, students knew that when they were in a “Watering hole” they should not just be socializing but sharing knowledge. Teachers as well were being challenged by leadership to reduce their “Campfire” time which effectively guided them from less lecture to more student-centred instruction. This use of archetypes as structure was effectively change management in disguise.

This strategy aligns with recent work on the sociomaterial view on the inhabitation of space in which “New school buildings matter…as effects of materializing processes in which school personnel and objects take part. The building gives the principal above ‘licence…to ask those bigger questions’ and to ‘crowbar’ the process of curriculum and pedagogic change” (Mulcahy, Cleveland, & Aberton, 2015, p. 10). The space is linked to text, technology, and artefacts in a circulatory fashion as pedagogic change and spatial change come to being together.

Next Steps and Future Application

The themes and examples presented here reflect early findings from initial thematic analysis and form the basis for further exploration. For example, the body of knowledge can be extended by broadening the suite of case studies beyond Australia and New Zealand and developing more in-depth analysis linking these to the original case studies. The highlighted example of “Layered Structuring” can be deepened, exploring both the relationship between the concentric layers of structure and identifying specific tools and strategies to be applied in each. The three categories of enablers can also be unpacked, each containing multiple specific strategies and tools, only one of which was highlighted in this chapter, that can inform future school design and transition processes. Another trajectory may be the refinement of these enablers and exploration of their relationships to one another to propose a systems-based approach to the school transition process.

While all of these proposed directions, among others, are feasible, it is desired that the next step for this research does focus on the applicability of this burgeoning knowledge. One opportunity is aligning with Phase 2 and 3 of the ongoing ILETC research in which tools and strategies to support the teacher transition process will be piloted and then disseminated at scale to test their efficacy (ILETC, 2016). This research focus is especially suited to the creation of tools to be applied alongside the design process of the ILE, leveraging most intensely the often-under-utilized period during construction to assist with the forthcoming educational transition. When done right, the goal is for schools to find their “buzz” sooner, rather than later.

Notes

- 1.

Two of the case study sites were within their first 2 years of occupation. One opened in 2011 and another in 2009. Participants in the older school were involved prior to opening and the design and transition process was well documented.

- 2.

Type C—Traditional classrooms with flexible walls and breakout space; Type D—Open plan with the ability for separate classrooms; Type E—Open plan with some adjoining spaces.

References

Barrett, P., Davies, F., Zhang, Y., & Barrett, L. (2015). The impact of classroom design on pupils’ learning: Final results of a holistic, multi-level analysis. Building and Environment,89, 118–133.

Biggs, J. B. (1987). Student approaches to learning and studying. Research monograph. Hawthorn: Australian Council for Educational Research.

Blackmore, J., Bateman, D., O’Mara, J., & O’Loughlin, J. (2011). Research into the connection between built learning spaces and student outcomes: Literature review. Victoria, Australia: Victorian Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

Cleveland, B., & Fisher, K. (2014). The evaluation of physical learning environments: A critical review of the literature. Learning Environments Research,17, 1–28.

Dovey, K., & Fisher, K. (2014). Designing for adaptation: The school as socio-spatial assemblage. The Journal of Architecture,19(1), 43–63.

HEFCE. (2006). Designing spaces for effective learning. UK: Higher Education Funding Council for England.

ILETC. (2016). Can altering teacher mind frames unlock the potential of innovative learning environments? Retrieved from https://www.flipsnack.com/iletc/flyerlayoutwebv1.html.

Imms, W., Mahat, M., Byers, T., & Murphy, D. (2017). Type and use of innovative learning environments in australasian schools. ILETC Survey No. 1, University of Melbourne, Melbourne. LEaRN, Retrieved from http://www.iletc.com.au/publications/reports/.

Mulcahy, D., Cleveland, B., & Aberton, H. (2015). Learning spaces and pedagogic change: envisioned, enacted and experienced. Pedagogy, Culture & Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2015.1055128.

Saltmarsh, S., Chapman, A., Campbell, M., & Drew, C. (2015). Putting “structure” within the space”: Spatially un/responsive pedagogic practices in open-plan learning environments. Educational Review,67(3), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2014.924482.

Thornburg, D. (2001, revised 2007) Campfires in cyberspace: Primordial metaphors for learning in the 21st century. Ed at a Distance 15(6). Retrieved from https://www.nsd.org/cms/lib/WA01918953/Centricity/Domain/87/TLC%20Documents/Other%20TLC%20Documents/CampfiresInCyberspace.pdf.

Yin, R. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods. Los Angeles: Sage.

Acknowledgements

Data utilized in this research was obtained in adherence to the required ethical protocol of the author’s host institution. All images and diagrams are the property of the author, or the author has obtained consent to use them from the appropriate copyright owner.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

French, R. (2021). School Change: Emerging Findings of How to Achieve the “Buzz”. In: Imms, W., Kvan, T. (eds) Teacher Transition into Innovative Learning Environments. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7497-9_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7497-9_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-7496-2

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-7497-9

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)