Abstract

The Sydney School of Veterinary Science (SSVS), University of Sydney, recognises the ever-increasing importance of cultural competence (CC) and cultural capacity in professional and research practice and has been working since 2012 on the embedding of CC into the pre-veterinary programmes: Bachelor of Veterinary Biology (BVB) and the Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM). During both their professional lives and while studying, veterinarians work in culturally and linguistically diverse teams and environments. Cultural perspectives can impact animal health, welfare and/or research outcomes and also relationships with communities. It is therefore important to build cultural capacity in graduates and prepare them with relevant skills such as the ability to reflect on cultural belief systems and worldviews present in themselves and in those with whom they interact. To address this, we introduced a broad framework (graduate qualities, learning outcomes and a rubric) that defines CC beyond the context of cultural and linguistic diversity and includes other self-defined cultural groups, and incorporates cultural awareness and competency for working across cultures. We embedded CC vertically into seven units of study within the pre-veterinary BVB and postgraduate DVM programmes. The major areas that were embedded include: Indigenous perceptions and knowledge about animals; principles of cultural competence; effective communication across cultures; and the impact of CC on professional practice, animal management and research. This initiative constitutes a crucial milestone for students and outcomes indicate that students have been inspired to develop core knowledge and skills in this critical area, skills which they will carry with them when approaching extramural rotations in remote communities and overseas, as well as in their future veterinary and animal science careers, including in their places of work. To date, one DVM class has graduated with an increased awareness of the importance of CC and ways to apply it, and many students have expressed that they see the relevance of CC in the curriculum and to their future careers.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

The Importance of Cultural Competence

There is a growing national and international recognition of the importance of cultural competence and capacity in education, professional practice and community work and its role in helping to facilitate development of relationships and creation of opportunities to work collaboratively and respectfully with groups from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds including First Nations Peoples (Bradley, Noonan, Nugent, & Scales, 2008, Universities Australia, 2011a, b). Aligning with this, international and local veterinary accrediting bodies and associations have recommended that cultural awareness, cultural competence and diversity competence should be incorporated as one of the core graduate qualities in veterinary education, and have developed a competency framework to guide their members in the endeavour to foster respect, and collaborate with and in culturally and socially diverse groups and environments to promote animal, human and environmental health and wellbeing (AVBC, 2016; Hodgson, Pelzer, & Inzana, 2013; Molgaard et al., 2018; NAVMEC, 2011).

The disciplines of health and medicine have developed foundational and best-practice approaches in cultural competence in professional practice (e.g., CARE, 2009; Goode, Harris Haywood, Wells, & Rhee, 2009; Kodjo, 2009; Kurtz & Adams, 2019; Sobo, 2009; Sobo & Loustaunau, 2010; Trudgen, 2000). This is also the case in One Health, when veterinarians are working in interdisciplinary environments and the following factors are also important: the human–animal–environment interface; understanding global issues; and community development (Kahn, Kaplan, Monath, & Steele, 2008; Maud, Blum, Short, & Goode, 2012; Zinsstag, Schellingm, Wyssm, & Mahamatm, 2005).

The 2016 Australian census highlights the richness and diversity of cultural and social groups which are the clients that veterinary students will be dealing with during their professional practice. Australia is a culturally, demographically and linguistically diverse country. This poses great challenges and opportunities for veterinarians, especially when Australia has the highest rate of pet ownership in the world (62% of households for ~24 million pets) (AMA, 2016). Here we describe and reflect on a journey we took to assist in servicing of these social realities that started in 2012 when we designed the rationale, learning outcomes, content and pedagogy to embed cultural competence into the curriculum of the combined Bachelor of Veterinary Biology (BVB) and Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (DVM) program at the Sydney School of Veterinary Science (SSVS).

Defining Cultural Competence in the Context of the Veterinary Programme at Sydney School of Veterinary Science

Cultural competence was the major focus of the current work, and it was defined as a graduate quality for the BVB and DVM programmes as follows: On graduation students will confidently and competently be able to demonstrate an understanding of the manner in which culture and belief systems impact delivery of veterinary medical care while recognising and appropriately addressing biases in themselves, in others and in the process of delivering their professional practices.

Elements of cultural humility (commitment to self-assessment to manage and reduce the power imbalances in the practitioner–client interface: Tervalon & Murray-García, 1998), intercultural competence (capacity to work productively and positively within professional, working and educational environments of diverse cultures and perspectives: Gurin, Dey, Hurtado, & Gurin, 2002; Lee et al., 2018) and multicultural competence (ability to work with and interact with others who are culturally different from oneself in meaningful ways: Chun & Evans, 2016; Pope, Reynolds, & Mueller, 2004), were also embedded into pedagogy and curriculum content.

Cultural Competence in the Veterinary Curriculum

Through a consultation process (meetings and workshops) that occurred during the design phase for the BVB and DVM programmes over two years, including Indigenous peoples and centres for cultural competence and benchmarking with other veterinary schools, we identified some guiding principles for our approach. These include making learning outcomes evident and assessable across the degree programme, focusing on a curriculum that is relevant and linked to the veterinary profession. Other principles include embedding cultural competence vertically across the programme in existing units that we thought suitable to presentation of the curriculum content in a way that demonstrates the relevance of the material for the veterinary profession. Thus, we designed a roadmap of learning outcomes, which correspond to 24 sessions of face-to-face teaching, tutorials and practicals and various pieces of independent work across seven units of study. Teaching of cultural awareness in particular about Indigenous cultures started in the pre-veterinary units of study while cultural competence and other levels of cultural capacity were further developed through years 1 to 3 of the DVM, so students were equipped with knowledge, skills and resources to prepare for their intramural and extramural, clinical and non-clinical, rotations that take place mainly in year 4 of the DVM programme.

We framed and mapped the learning outcomes in a progressive way. Specifically, we take students through cognitive and affective domains (Bloom, 1956; Krathwohl & Anderson, 2009; Lynch, Russell, Evans, & Sutterer, 2009; O’Neill & Murphy, 2010) when understanding principles of cultural competence, their application to approaching real and simulated case scenarios underlined by reflections on the impact of the human–animal bond, and unconscious biases on interactions with clients and communities across cultural settings.

After considering a range of potential pedagogical approaches, we agreed that using a repertoire of teaching and learning methods would suit the multicultural and diverse international and local student cohort of the BVB and DVM programmes. We supported a vision for the teaching of cultural competence so that the skills, behaviours and values developed in students are considered to go deeper than only outcomes related to awareness of concepts.

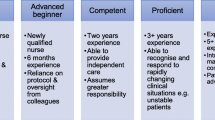

Through diverse pedagogical approaches (Brockbank & McGill, 2007; Gewurtz, Coman, Dhillon, Jung, & Solomon, 2016; Kapur, 2008; Roselli, 1999; Strijbos & Fischer, 2007; Solomon, 2005; Sugerman, Doherty, & Garvey, 2000), we facilitated and fostered transformational learning to give students the opportunity to make a major shift in their perspective on the world, including in relation to areas like gender, race and class. We also supported students to take a critical perspective on the dominant culture. We approached curriculum content by following an adapted cultural competence continuum from cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural sensitivity to cultural competence (Cross, Bazron, Dennis, & Isaacs, 1989, 2012; Chun & Evans, 2016; Farrelly & Lumby, 2009; Kiefer et al., 2013). We also enhanced understanding about the concept of cultural competence by introducing other dimensions and elements of cultural capacity such as diversity competence, cultural responsiveness, cultural humility, intercultural competence and multicultural competence (Abermann & Gehrke, 2016; Alvarez, Gilles, Lygo-Baker, & Chun, 2019; Bennet et al., 2004; Bennett, 2004; Bennett & Bennett, 2004; Brown, Thompson, Vroegindewey, & Pappaioanou 2006; Gallardo, Johnson, Parham, & Carter, 2009; Ippolito, 2007; Tervalon & Murray-García, 1998; Wagner & Brown, 2002) as illustrated (Fig. 6.1).

Highlights of the Implementation

Pre-veterinary Bachelor of Veterinary Biology Units of Study

The units of study topics included use of animals across cultures, non-human kin relationships in Indigenous cultures, Indigenous practices and knowledges in conservation and management of biodiversity, and weather knowledge related to animals (Green, Billy, & Tapim, 2010; Hart, 2010; Kutay, Mooney, Riley, & Howard-Wagner, 2012; Moller, Berkes, Lyver, & Kislalioglu, 2004). Various methods were used including co-teaching with Indigenous knowledge holders and development of or use of publicly available resources under the guidance of these knowledge holders. Students had the opportunity to engage with smoking ceremonies, cultural performances and workshops related to the presence and significance of animals in Indigenous dance, songs, paintings and storytelling.

Doctor of Veterinary Medicine

Cultural competence was introduced to DVM students as part of a One Health field trip activity in a local parkland frequented by humans, dogs, horses and wildlife. Students rotated through five learning stations focussing on: animal health; animal management; infectious diseases; zoonoses; and the impact of cultural competence and bias on the profession. This work is further described in Mor et al. (2018). Subsequently, we engaged students in individual and group reflections on their own and others’ perceptions of animals and the significance of this when interacting with clients, with use of pre-recorded talks by people from diverse cultural heritages. Students were engaged in learning principles of culture, cultural diversity and cultural competence with a particular emphasis on unconscious and conscious biases and stereotypes and strategies to manage these.

Students were engaged in a class reflection on potential questions about the benefits of veterinarians learning about effective communication in cross-cultural environments. The focus was on principles of culturally effective communication across cultural environments and social groups as well as strategies to deal with tensions in cross-cultural environments (Adams, 2009; Bonvicini & Keller, 2006; Kodjo, 2009; Kurtz, 2006; Shaw, 2006). Students were also engaged in strategies related to the practice of active listening, types of questions and communication strategies in cross-cultural settings.

Teaching was structured to give students the opportunity to work through case studies based on experiences of practitioners and students during overseas placements and a space for self-reflection on conscious and unconscious biases and power-imbalance between practitioner and client, and ways of managing these challenges. To provide a context for cultural competence, one case study focused on shelter practice, veterinary euthanasia and cultural influences in Bangkok, Thailand.

Cultural competence was integrated within the topic of Animal Management Systems. Case studies on animal husbandry and management in rural and remote Australia and overseas were used to reflect on cultural competence opportunities and challenges. This included management of a conservation programme, and animal health in remote Australian Indigenous communities.

The pedagogy and curriculum content was one of the most complex in the DVM programme. It focused on the relevance and practice of cultural competence in research practice (Papadopoulos & Lees, 2002; Shalowitz et al., 2009) and community-based work and included all of the cultural capacity aspects described in previous units, but developed further. Students were introduced to the general aspects of the ethical and working guidelines (Queensland Health, 2015; NHMRC, 2018; RACGP, 2012) and history of dispossession, trauma, sorry business, gender roles, non-human kinship relationships and ethical guidelines when undertaking research in Indigenous communities by using the University of Sydney’s Aboriginal Kinship Module and the Aboriginal Sydney Massive Open Online Courses.

Discussion

We have embedded diverse dimensions of cultural capacity, with an emphasis on cultural competence and some elements of intercultural competence and cultural humility, into pedagogy and content in seven units of study across the BVB and DVM programmes in the SSVS. This vertical integration of principles of theory and practice into veterinary curriculum addresses some of the recommendations by the international and local accreditation and association bodies for veterinary education (AVBC, 2016; Hodgson et al., 2013; Molgaard et al., 2018; NAVMEC, 2011). This work is a practical example of how to develop important non-technical skills in BVB/DVM students and graduates, so they are in a better position to engage effectively and respectfully with the global and local context of their professional practice, including in animal conservation, program management and community development (Brown et al., 2006; Graham, Turk, McDermott, & Brown, 2013; Kiefer et al., 2013; Shaw, 2006; Wagner & Brown, 2002).

The approach adopted was to introduce students to fundamental levels related to awareness which was scaffolded onto more complex levels of cultural competence and humility. The ultimate aim is to enhance students’ ability to reflect on the impact of cultural belief systems present in themselves and in those they interact with during their professional practice across different cultural environments, diverse social groups and within intercultural settings. Furthermore, this work provided opportunities for students to increase awareness of the historical context of dispossession, exclusion, inequity and injustice towards minorities and underrepresented groups such as Aboriginal peoples, and how this has generated intergenerational trauma (e.g., Atkinson, 2013; Brice, 2004; Bobba, 2019) that needs to be considered in professional practice. This awareness and the incorporation of some Indigenous perspectives as well as the contribution to a better climate and environment that celebrates and recognises Indigenous cultures is a first step towards decolonising (Harvey & Russell-Mundine, 2019) the veterinary curriculum.

The current work has contributed to the implementation of the principles recommended by Universities Australia (2011a, b) by enhancing the cultural capacity of veterinary students and developing a more inclusive veterinary curriculum that celebrates and recognises the contributions and cultures of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. We consider that this curriculum work is also having a positive influence in fostering inclusive classroom environments for the retention of and satisfactory achievement by Indigenous students (Drysdale, Chesters, & Faulkner, 2006; Oliver, Rochecouste, & Grote, 2013). The SSVS has also influenced cultural change across the University of Sydney as it has been considered one of the best practice examples for the integration of CC into curriculum. We found that when the University of Sydney established cultural competence as one of the graduate qualities for all academic programmes and developed a rubric to assess this, there was significant alignment of requirements with what we had developed for the BVB and DVM programmes since 2012.

Conclusions

We have enhanced cultural capacity in veterinary students by integrating cultural competence vertically into curriculum and developing contextual learning activities with increasing sophistication to align with students’ interests and to progress them along the cultural competence continuum. This work has contributed to a trend of positive change in behaviours and attitudes in veterinary students to give them foundational skills in cultural competence to effectively and respectfully interact within multicultural and diverse social environments. To achieve this, we have introduced students to the cultural competence concept, allowing them to identify the challenges when working in cross-cultural environments, develop strategies and then implement them through repetition, reinforcement and reflection.

References

Abermann, G., & Gehrke, I. (2016) The Multicultural classroom—a guaranteed intercultural learning space? Research Forum at the Austrian University of Applied Sciences 2016 (S. 1–7), Wien.

Alvarez, E. E., Gilles, W. K, Lygo-Baker, S., & Chun. R. (2019). Teaching cultural humility and implicit bias to veterinary medical students: a review and recommendation for best practices. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.1117-173r1.

Animal Medicines Australia. (2016). Pet Ownership in Australia. Barton ACT.

Atkinson, J. (2013). Trauma-informed services and trauma-specific care for Indigenous Australian children. Resource sheet no. 21 produced for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

Australasian Veterinary Boards Council. (2016). Accreditation standards Version 5.

Bennett, J. M., & Bennett, M. J. (2004). Developing intercultural sensitivity. an integrative approach to global and domestic diversity. In: DaLandis, J. Bennett, & M. Bennett (Eds.) Handbook of Intercultural Training, 3rd Edition. (pp. 147–165). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Bennett, M. J. (2004). Becoming interculturally competent. In J. S. Wurzel (Ed.), Toward multiculturalism: A reader in multicultural education (2nd ed., pp. 62–77). Newton, MA: Intercultural Resource Corporation.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain. New York: McKay, pp. 20–24.

Bobba, S. (2019). Ethics of medical research in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. Australian Journal of Primary Health. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY18049.

Bonvicini, K., & Keller, V. F. (2006). Academic faculty development: the art and practice of effective communication in veterinary medicine. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 33(1), 50–57.

Bradley, D., Noonan, P., Nugent, H., & Scales, B. (2008). Review of Australian higher education: Final report. Available from https://vital.voced.edu.au/vital/access/services/Download/ngv:32134/SOURCE2.

Brice, G. (2004). A way through? Measuring Aboriginal mental health/social and emotional well-being: community and post-colonial perspectives on population inquiry methods and strategy development. Monograph. Canberra: National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation Inc.

Brockbank, A., & McGill, I. (2007). Facilitating reflective learning in higher education. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Brown, C., Thompson, S., Vroegindewey, G., & Pappaioanou, M. (2006). The global veterinarian: The why? The what? The how? Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 33(3), 411–415.

CARE: Community Alliance for Research and Engagement. (2009). Principles and guidelines for community university research partnerships. CARE Ethical Principles of Engagement Committee: Yele Center for Clinical Investigation.

Chun, E., & Evans, A. (2016). The politics of cultural competence in higher education in: Rethinking cultural competence in higher education: An ecological framework or student development.

Cross, T. L., Bazron, B. J., Dennis, K. W., & Isaacs, M. R. (1989). Towards a culturally competent system of care: A monograph on effective services for minority children who are severely emotionally disturbed. Washington, DC: CASSP Technical Assistance Center.

Cross, T. L. (2012). Cultural competence continuum. Journal of Child and Youth Care Work, 24, 83–85.

Drysdale, M. M., Chesters, J. E., & Faulkner, S. (2010). Footprints forwards: Better strategies for the recruitment, retention and support of Indigenous medical students. In A. Larson, & D. Lyle (Eds.), A bright future for rural health: Evidence-based policy and practice in rural and remote Australian health care (pp. 26–30). Australian Rural Health Education Network.

Farrelly, T., & Lumby, B. (2009). A best practice approach to cultural competence training. Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal, 33(5), 14–22.

Gallardo, M. E., Johnson, J., Parham, T. A., & Carter, J. A. (2009). Ethics and multiculturalism: Advancing cultural and clinical responsiveness. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(5), 425–435. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016871.

Gewurtz, R. E., Coman, L., Dhillon, S., Jung, B., & Solomon, P. (2016). Problem-based learning and theories of teaching and learning in health professional education. Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, 4(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.14297/jpaap.v4i1.194.

Goode, T., Harris Haywood, S., Wells, N., & Rhee, K. (2009). Family-centered, culturally, and linguistically competent carte: essential components of the medical home. Pediatric Annals, 38(9), 505–512. https://doi.org/10.3928/00904481-20090820-04.

Graham, T. W., Turk, J., McDermott, J., & Brown, C. (2013). Preparing veterinarians for work in resource-poor settings. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 243(11), 1523–1528. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.243.11.1523.

Green, D., Billy, J., & Tapim, A. (2010). Indigenous Australians’ knowledge of weather and climate. Climatic Change, 100(2), 337–354.

Gurin, P., Dey, E. L., Hurtado, S., & Gurin, G. (2002). Diversity and higher education: Theory and impact on educational outcomes. Harvard Educational Review Home, 72(3), 330–367. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.72.3.01151786u134n051.

Hart, M. A. (2010). Indigenous worldviews, knowledge, and research: The development of an indigenous research paradigm. Journal of Indigenous Voices in Social Work, 1(1), 1–16.

Harvey, A., & Russell-Mundine, G. (2019). Decolonising the curriculum: Using graduate qualities to embed Indigenous knowledges at the academic cultural interface. Teaching in Higher Education, 24(6), 789–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1508131.

Hodgson, J. L., Pelzer, J. M., & Inzana, K. D. (2013). Beyond NAVMEC: Competency-based veterinary education and assessment of the professional competencies. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 40(2), 102–118. https://doi.org/10.3138/jvme.1012-092R.

Ippolito, K. (2007). Promoting intercultural learning in a multicultural university: Ideals and realities. International Journal of Educational Research, 12(5–6), 749–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510701596356.

Kahn, L. H., Kaplan, B., Monath, T. P., & Steele, J. H. (2008). Teaching ‘‘one medicine, one health”. American Journal of Medicine, 121(3), 169–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.09.023.

Kapur, M. (2008). Productive failure. Cognition and Instruction, 26(3), 379–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370000802212669.

Kiefer, V., Grogan, K. B., Chatfield, J., Glaesemann, J., Hill, W., Hollowell, B., ... & Urday, K. (2013). Cultural competence in veterinary practice. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 243(3), 326–328.

Kodjo, C. (2009). Cultural competence in clinician communication. Pediatric Review, 30(2), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.30-2-57.

Krathwohl, D. R., & Anderson, L. W. (2009). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Kurtz, S. (2006). Teaching and learning communication in veterinary medicine. Journal of Veterinary Medical Education, 33(1), 11–19.

Kurtz, S. M., & Adams, C. L. (2009). Essential education in communication skills and cultural sensitivities for global public health in an evolving veterinary world. Revue Scientifique et Technique, 28(2), 635–647.

Kutay, C., Mooney, J., Riley, L., & Howard-Wagner, D. (2012). Experiencing Indigenous Knowledge online as a community narrative. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education., 41(1), 47–59. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2012.8.

Lee, A., Poch, R., Smith, A., Kellym, M. D., & Leopold, H. (2018). Intercultural pedagogy: A Faculty Learning Cohort. Education Sciences, 8(4), 177. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040177.

Lynch, D. R., Russell, J. S., Evans, J. C., & Sutterer, K. G. (2009). Beyond the cognitive: the affective domain, values, and the achievement of the vision. Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 135(1), 47–56.

Maud, J., Blum, N., Short, N., & Goode N. (2012) Veterinary students as global citizens: exploring opportunities for embedding the global dimension in the undergraduate veterinary curriculum. (DERC research papers 32). Royal Veterinary College and Development Education Research Centre, Institute of Education.

Molgaard, L. K., Hodgson, J. L., Bok, H. G. J., Chaney, K. P., Ilkiw, J. E., Matthew, S. M., et al. (2018). Competency-based veterinary education: Part 1—CBVE Framework. Washington, DC: Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges.

Moller, H., Berkes, F., Lyver, P. O. B., & Kislalioglu, M. (2004). Combining science and traditional ecological knowledge: monitoring populations for co-management. Ecology and Society, 9(3), 2.

Mor, S., Norris, J., Bosward, K., Toribio, J., Ward, M., Gongora, J., et al. (2018). One health in our backyard: Design and evaluation of an experiential learning experience for veterinary medical students. One Health, 5, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.onehlt.2018.05.001.

NMHMR: National Health and Medical Research Council. (2018). Ethical conduct in research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and communities: Guidelines for researchers and stakeholders. Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra.

North American Veterinary Medical Education Consortium (NAVMEC). Roadmap for Veterinary Medical Education in the 21st Century. Report and recommendations. 2011.

O’Neill, G., & Murphy, F. (2010). Guide to taxonomies of learning. UCD Teaching & Learning. Available from http://www.ucd.ie/t4cms/UCDTLA0034.pdf.

Oliver, R., Rochecouste, J., & Grote, E. (2013). The transition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students into higher education. Sydney, NSW: Office of Learning and Teaching. Department of Education. Australian Government. Available from https://ltr.edu.au/resources/SI11_2137_Oliver_Report_2013.pdf.

Papadopoulos, I., & Lees, S. (2002). Developing culturally competent researchers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 37(3), 258–264.

Pope, R., Reynolds, A. L., & Mueller, J. A. (2004). Multicultural competence in student affairs. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Queensland Health. (2015). Sad News, Sorry Business: Guidelines for caring for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people through death and dying. State of Queensland (version 2). Available from http://healthbulletin.org.au/articles/sad-news-sorry-business-guidelines-for-caring-for-aboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people-through-death-and-dying/.

RACGP: Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (2012)- An introduction to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health cultural protocols and perspectives. South Melbourne, Victoria.

Roselli, N. (1999). El mejoramiento de la interacción sociocognitiva mediante el desarrollo experimental de la cooperación auténtica. Interdisciplinaria, 16(2), 123–151.

Shalowitz, M. U., Isacco, A., Barquin, N., Clark-Kauffman, E., Delger, P., Nelson, D., et al. (2009). Community-based participatory research: A review of the literature with strategies for community engagement. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 30(4), 351–361. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181b0ef14.

Shaw, J. R. (2006) Four core communication skills of highly effective practitioners. Veterinary clinics of North America. Small Animal Practice, 36(2), 385–396.

Sobo, E., & Loustaunau, M. (2010). The cultural context of health, illness and medicine. 2nd ed. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. Sobo, E. (2009). Culture and meaning in health services research: an applied anthropological approach. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; 2009.

Solomon, P. (2005). Problem-based learning: A review of current issues relevant to physiotherapy education. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 21(1), 37–49.

Strijbos, J., & Fischer, F. (2007). Methodological challenges for collaborative learning research. Learning and Instruction, 17(4), 389–393.

Sugerman, D. A., Doherty, K. L., & Garvey, D. E. (2000). Reflective learning: theory and practice. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Co.

Lee, A., Poch, R., Shaw, M., & Williams, R. D. (2012). Engaging diversity in undergraduate classrooms–a pedagogy for developing intercultural competence. ASHE Higher Education Report, 38(2), 1–132.

Tervalon, M., & Murray-García, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125.

Trudgen, R. (2000). Why warriors lie down and die: towards an understanding of why the Aboriginal people of Arnhem Land face the greatest crisis in health and education since European contact. Darwin: Aboriginal Resource & Development Services.

Universities Australia. (2011a). Guiding Principles for Developing Indigenous Cultural Competency in Australian Universities, October, DEEWR, 1–32. Canberra.

Universities Australia. (2011b). National best practice framework for indigenous cultural competency in Australian universities, October, DEEWR, 1–422. Canberra.

Wagner, G. G., & Brown, C. C. (2002). Global veterinary leadership. Veterinary Clinics of North America. Food Animal Practice, 18(3), 389–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-0720(02)00034-8.

Zinsstag, J., Schellingm, E., Wyssm, K., & Mahamatm, M. B. (2005). Potential of cooperation between human and animal health to strengthen health systems. Lancet, 366(9503), 2142–2145. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67731-8.

Acknowledgments

The offices of the Deputy Vice-Chancellor Indigenous Strategy and Services, and Education, University of Sydney, have supported this work financially through Indigenous compacts and grants. We would also like to acknowledge the valuable advice given during interactions with Dr Gabrielle Russell from the University of Sydney’s National Centre for Cultural Competence and A/Prof Tawara D. Goode from Georgetown University’s National Center for Cultural Competence.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gongora, J., Vost, M., Zaki, S., Sutherland, S., Taylor, R. (2020). Fostering Diversity Competence in the Veterinary Curriculum. In: Frawley, J., Nguyen, T., Sarian, E. (eds) Transforming Lives and Systems. SpringerBriefs in Education. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-5351-6_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-5351-6_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-5350-9

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-5351-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)