Abstract

Exogenous deaths occur more often than expected. According to demographic statistics, exogenous deaths such as suicide and accidental death make up around 5% of the total number of deaths in Japan [1]. These numbers also include accidental deaths such as falling, drowning, injuries from smoke and flame, asphyxiation, and poisoning, as well as murders. In other words, exogenous deaths cover almost all deaths other than those categorized as illness and natural causes. In 2006, suicide prevention was recognized as a crucial task in public health because of the succession of years in which the total number of suicides tallied over 30,000. This situation saw the establishment of the Basic Act on Suicide Prevention in 2006.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Exogenous deaths occur more often than expected. According to demographic statistics, exogenous deaths such as suicide and accidental death make up around 5% of the total number of deaths in Japan [1]. These numbers also include accidental deaths such as falling, drowning, injuries from smoke and flame, asphyxiation, and poisoning, as well as murders. In other words, exogenous deaths cover almost all deaths other than those categorized as illness and natural causes. In 2006, suicide prevention was recognized as a crucial task in public health because of the succession of years in which the total number of suicides tallied over 30,000. This situation saw the establishment of the Basic Act on Suicide Prevention in 2006.

Several research studies have clarified that there are strong correlations between exogenous deaths and socioeconomic factors (SES). For example, the Japan Collaborative Cohort (JACC) Study for Evaluation of Cancer Risk found that people with a low academic level (aged 15 years or younger; junior high school level) are 1.8 times more likely to die by exogenous means than those with a high academic level (aged 19 years or over; college or university level) [2].

Of the different exogenous deaths, this chapter focuses on suicide in particular, and introduces studies that have investigated its correlation with SES. Furthermore, the discussion also considers possible interventions against socio-environmental factors to prevent suicide.

2 Status Quo and Analysis

2.1 The Status Quo of Suicide in Japan

An international comparison by the World Health Organization (WHO) showed that the suicide rate in Japan has been the highest among the G7 countries (Fig. 9.1). Such trends can be used to explore negative correlations between each country’s suicide rate and social indicators such as marriage rate, gross domestic product, and natural population growth rate. Thus, committing suicide can be triggered by factors such as being single (or loneliness), low-income, and living in a depopulated area [3]. Temporal changes in Japan show that the number of suicide victims increased drastically in 1998 by about 8000 (30% increase from the previous year) to give an abnormally high number of suicide deaths surpassing 30,000 for 12 years in a row (Fig. 9.2). However, since 2010, the number of suicides has decreased each year to around 21,000 in 2016 (35% decrease from 2003).

International comparison of suicide and accidental death rate between G7 countries [population demographic statistics, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW)]. Note: “Mortality rate” refers to the number of deceased persons per 100,000 persons in the population. (Reference source: World Health Organization documentation (December 2016))

To help analyze the causes behind these trends, the National Police Agency (NPA) revised the suicide statistic registration slip in 2007, allowing up to three resources to corroborate that the death was suicide, and including attribution of the cause and motivation. The result showed that the most common reason for suicide was “health-related issues” with around 10,800 victims, followed by “financial and social problems” with around 3500 victims (Fig. 9.3) [4].

Around 70% of suicide victims in Japan are male. However, the lifelong prevalence rate of depression in Japan is around 5% for males and around 10% for females [5]. This implies that suicide ideation from mental illnesses cannot fully explain the causes of suicide. Thus, suicide may need to be analyzed by taking SES into account as one of the background factors.

2.2 Ecological Analysis Focusing on Regional, Ethnic, and Generational Factors

Fukuda et al. [6] compared samples by dividing into five groups, using SES (i.e., average income and academic history of residents) by municipalities in 1965. The municipalities with the lowest SES had more than 1.4 times higher suicide mortality rates than the municipalities with the highest SES. The trends in this data showed that the ratio had expanded to more than 1.6 times in 1990 [7]. In an Australian study conducted during the same period, regions were similarly divided into five groups. This study also indicated that the district with the lowest SES had a suicide mortality rate more than 1.4 times that of the district with the highest SES [8, 9].

Such disparities are not only seen among regions, but also among racial minorities that have historically been exposed to socioeconomic difficulties and received discrimination and abuse (Native Americans, Alaskan Natives, Maoris, Aborigines, and Korean residents in Japan). These groups have twice the suicide mortality rate than the average for where they are living (Fig. 9.4) [10, 11].

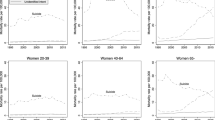

Although the suicide rate was low during World War II and during periods of high economic growth, studies have shown that suicide rate increased during the chaotic times immediately after the end of the War, from around 1955, around 1985, and when Japan experienced recession, as in 1998 (Fig. 9.5) [12, 13]. Sawada et al. [14] found a significant statistical correlation between unemployment rate and suicide mortality [15, 16]: correlation coefficient R = 0.911.

Furthermore, Émile Durkheim argued a birth cohort effect, in which a group born during the same generation exhibits a certain tendency in his Study of Suicide more than a century ago [17]. Experiencing major stress (i.e., poverty and militarist education during wartime) during one’s susceptible infancy instills mental vulnerability. Thus, as years go by, these infants grow up and become unable to tolerate major socioeconomic changes (i.e., recession and associated unemployment), leading to taking their own lives. Recent epidemiology trends have also seen a gradual verification of the long-term (life course) impact; the biological and social factors during infancy can later influence the health state and illnesses during adulthood [18]. For example, a birth cohort of over 5300 subjects in Finland showed that approximately 80% of 27 men who attempted or committed suicide had suffered psychological problems by the age of 8 years [19]. In other words, low SES factors such as divorce, low income, depopulation, unprivileged ethnicity, recession, unemployment, and poor historical environment during infancy may exist in the backdrop of suicide [20].

2.3 Analysis Focusing on Individual Factors

According to the population demographic statistics published by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) to investigate the background of suicide victims, 70% of victims are adult males, and, in particular, 63% are unemployed. However, from 1998 onward when the suicide increased drastically, it was revealed that the suicide rates of employed and self-employed individuals also increased as it did for unemployed individuals (Fig. 9.6). This fact may indicate that people take their own lives after becoming unemployed through corporate downsizing, but at the same time, people who have stayed in the workplace have considerable stress, which may be a consequence of excessive workload (after forced redundancies) or uncertainty about the future.

Because studies that investigate individual etiologies in detail use an individual’s private information, approval from the subject is required. However, it is impossible to earn the consent from victims of suicide. Furthermore, touching on the details of suicide may be considered taboo, and an individual analysis that goes back to the causes and motivation of suicide will be difficult. However, with the Basic Act on Suicide Prevention as an impetus, the Center for Suicide Prevention finally started to conduct psychological autopsy for clarifying actual conditions. They interviewed the family members and friends who knew the deceased well, based on the premise of providing care toward survivors [21].

Based on the data from over 300 suicide victims, there was an average of four reasons for people to take their own lives, confirming that the process that led up to suicide was by no means simple. The most common factors included family discord, exhaustion from taking care of senior citizens, multiple debts, bankruptcy, human relationships at work, unemployment, business slump, overwork, and depression.

3 Suggestion of Countermeasures

Partially because suicide has been considered as an individual issue, most administrative measures against suicide have only pertained to the health division such as depression countermeasures. However, suicide has been recognized as a significantly political issue involving the entire government and the focus was shifted from just the “cause” to the “cause of cause.” Furthermore, it was confirmed that suicide needs to be prevented using multilateral initiatives, such as measures against bullying at schools and mental health awareness at workplaces.

Finland is one of the countries that has achieved significant suicide prevention measures, and psychological autopsies have been conducted with almost all surviving families of the suicide victims. The national suicide prevention strategy has taken shape through support toward those who attempted suicide, collaboration with the police, and measures against drug and alcohol dependency. In addition, lifestyle support for youths and unemployment countermeasures were conducted even during the adverse time of an economic slump around 1990. As a result, Finland was successful in reducing the suicide mortality rate by 30% within a decade [13, 19]. Surprisingly the total participation-type countermeasures had been supported by the awareness of all citizens (Fig. 9.7). In South Korea, where the situation is very similar to Japan with its high suicide rate, a Comprehensive 5-Year Suicide Prevention Measure was formulated in which unemployed, divorcees, depression patients, and those who were close to suicide victims were perceived as a high-risk group. The policy aims for the society as a whole to take proactive responses, including enhancement of a consultation system and induction of early treatments.

In the previously mentioned Durkheim’s Study of Suicide, egoistic suicide was also discussed [17]. He described this type of suicide as being caused by the excessive loneliness and frustration resulting from the weakening of ties between individuals and the group. Egoistic suicide was said to have increased by the spread of individualism that took place after the industrial revolution [16]. At the time in Europe, the suicide rate was higher in the city than in the country, and higher among unmarried individuals than those that were married. Analysis of these trends found that modernized society weakened the bond of groups (i.e., regional and occupational) , causing the isolation of society members. Furthermore, Lane has also argued for the relation between the drastic increase in depression and the weakening of social ties caused by social pressure on saving time and the rise of a consumer culture [22, 23]. Motohashi et al. [5] claim that richness of social capital, which represents strong social bonds (i.e., social support, network, and sense of trust), is helpful in preventing suicide. In other words, having residents feel a sense of attachment to their region and having trust for one another, improves solidarity and brings about public safety [24].

Thus, an effort made by whole society in suicide prevention may be effective. The WHO also released A Guideline for National Strategies and Their Practice. This guideline advocates twelve comprehensive approaches (Table 9.1).

4 Summary

Suicide is an extremely individual issue. However, suicide is a social structural issue at the same time [4]. Based on past findings, countermeasure initiatives should not be limited to raising the awareness on mental health problems such as depression. Instead, for a more fundamental solution, it is necessary to focus on SES, which is indicative of the background factors behind suicide. Social security policies for income and livelihood should be positioned as a suicide prevention method along with policies of creating a livable regional society. Not only “health policy” but also “policy in health” is much anticipated.

References

Statistics and Information Policy Department, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Handbook of health and welfare statistics; 2018, pp. 1–30.

Fujino Y, et al. A nationwide cohort study of educational background and major causes of death among the elderly population in Japan (the JACC study group). Prev Med. 2005;40:444–51.

Watanabe N, et al. Regional differences of suicide. Mental Sci. 2004;118:34–9.

Health and Welfare for Persons with Disabilities Department, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. White Paper on comprehensive measures to prevent suicide; 2019, pp. 1–5, 14.

Motohashi Y, et al. Suicide can be prevented. Supika; 2005.

Fukuda Y, et al. Cause-specific mortality differences across socioeconomic position of municipalities in Japan, 1973-77 and 93-98: Increased importance of injury and suicide in inequality for ages under 75. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:100–9.

Fujita T. Rapid increase of suicide deaths in metropolitan areas. J Natl Inst Public Health. 2003;52(4):301.

Page A, et al. Divergent trends in suicide by socio-economic status in Australia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(11):911–7.

Taylor R, et al. Mental health and socio-economic variations in Australian suicide. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(7):1551–9.

Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander suicide prevention strategy; 2013, pp. 11–12.

Ishihara A, et al. Suicidology special. J Ment Health. 2003;49.

Cabinet Office. White Paper on suicide prevention; 2007.

Ministry of Health, Labour & Welfare. Population demographic statistics and labor force survey No 598; 2010, pp. 59.

Sawada Y, et al. Correlation between recession, unemployment and suicide, No 598; 2010, pp. 59.

Inoue K, et al. The report in the correlation between the factor of unemployment and suicide in Japan. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2008;29(2):202–3.

Shah A. Possible relationship of elderly suicide rates with unemployment in society; a cross-national study. Psychol Rep. 2008;102(2):398–400.

Durkheim É. The study of suicide; 1897.

Kondo K. Life course approach; prescription for health inequality society. Public Health Nurse J. 2006;62(11):946–52.

Sourander A, et al. Childhood predictors of completed and severe suicide attempts; findings from the Finnish 1981 birth cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(4):398–406.

Fujita T, et al. On the state of suicide seen from the population demographic statistics. 2nd national conference material for prefecture supervising managers on suicide countermeasure, 2009.

Fujino Y, et al. Prospective cohort study of stress, life satisfaction, self-rated health, insomnia, and suicide death in Japan. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35(2):227–37.

Center for Suicide Prevention. White Paper on the actual state of suicide; 2013, pp. 1–5.

Lane R. Friendship or commodities? The road not taken: friendship, consumerism, and happiness. Crit Rev. 1994;8(4):521–54.

Kawachi I. The health of nations: why inequality is harmful to your health. New York: The New Press; 2002.

WHO. Preventing suicide: global imperative (SUPRE); 2014, pp. 33–35.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Tanaka, G., Kondo, K. (2020). Suicide. In: Kondo, K. (eds) Social Determinants of Health in Non-communicable Diseases. Springer Series on Epidemiology and Public Health. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1831-7_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1831-7_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-1830-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-1831-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)