Abstract

An individual’s health is influenced not only by genetic inheritance and/or personal lifestyle but also by social factors, including socioeconomic status (SES), which may reflect income, years of education, or social status. Most research in the field of depression is concentrated on the symptoms, and the biological and cognitive-behavioral explanations and treatments. A socioeconomic perspective offers different possibilities to approach this disorder and to apply prevention measures. To date, studies in Japan and abroad have repeatedly demonstrated that people with lower SES are more susceptible to various forms of illnesses. This chapter explores the extent to which such health inequalities are present in depression.

Chiyoe Murata revised and added new findings to the original manuscript written in Japanese.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

An individual’s health is influenced not only by genetic inheritance and/or personal lifestyle but also by social factors, including socioeconomic status (SES), which may reflect income, years of education, or social status. Most research in the field of depression is concentrated on the symptoms, and the biological and cognitive-behavioral explanations and treatments. A socioeconomic perspective offers different possibilities to approach this disorder and to apply prevention measures. To date, studies in Japan and abroad have repeatedly demonstrated that people with lower SES are more susceptible to various forms of illnesses. This chapter explores the extent to which such health inequalities are present in depression.

Symptoms of depression include depressed moods, loss of interest in usual activities, and loss of appetite. If depression is prolonged, it will start to interfere with daily life, and, in some cases, it may even result in suicidal ideations or an actual suicide [1]. When we refer to the mental disorder, we usually use the term “major depression,” although “depressive state/episode” is used when a person scores above the critical threshold on a screening test for depression and shows a variety of depressive symptoms. In this chapter, we use the term “depression” to refer to a broader definition that includes both a depressive state and the depressive disorder.

The prevalence of depression is highest among people suffering from other mental disorders. According to the Global Health Estimates published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017 [1], more than 300 million people, or 4.4% of the world population, are suffering from depression. The report shows that the prevalence rate of depression increases with age. For example, almost 8% of women and 5.5% of men aged 60–64 years suffer from depression, compared with about 3% and 4.5%, respectively, for women and men aged 15–19 years. According to a study conducted from 2000 to 2001 [2] with 5363 senior citizens in four municipalities, 8.4–12.0% were found to be in a state of severe depression, scoring 10 points or higher on the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15). In another study from 2003 [3] that used the same scale to assess senior citizens of 15 municipalities (excluding senior citizens who had been issued the Certification of Needed Long-Term Care), 8.1% were found to be in a state of severe depression. The average prevalence rate of depression in North America and Europe is estimated to be 9% [4], with a report [5] claiming that the lifetime prevalence in the USA was up to 16.2%. According to research conducted between July and September 2017 by the Japan Productivity Center [6], 24.4% of the companies that took part in the research stated that mental disorders, including depression, had been increasing in the past 3 years. According to the study, the peak of this trend was in 2006, when the majority of the companies (61.5%) had reported mental disorders among their workers. The number of workers suffering from mental disorders remains high, which has led to an increasing societal concern about depression. Depression is not only closely related to suicide [1], but is also a risk factor for developing heart disease [7] and is a predictive factor for the need for long-term care in the future [8]. Furthermore, the relationship between depression and the onset of dementia has also been pointed out [9]. The impact of depression on society is significant; depression was ranked fifth out of all illnesses in 2016 in terms of its burden on society according to the forecast of the WHO in the Global Burden of Disease, based on the Disability-Adjusted Life Year (DALY) measurement [10].

2 Depression and Socioeconomic Status

Although the causes involved in the etiology of depression could be physiological (e.g., medication or illnesses such as cerebrovascular disease) as well as psychosocial (e.g., stress) [11], the following sections mainly examine the psychosocial factors related to depression. To date, reasonably consistent data have been reported about depression being common among groups with lower SES [11]. A meta-analysis [4] (statistical analysis after integrating data from multiple papers) of 56 research papers from 1979 onward that examined the relation between SES (income, education, and occupation) and depression showed that people with the lowest SES were 1.25 times more likely to develop depression than those with higher SES. Moreover, it was found that the duration of suffering from depression was 1.25 times longer and depression was 1.81 times more common among people from the lowest SES. The Whitehall II study11 with British public servants reported that depression was more common among people in lower-level job positions. A research paper [12] on 2472 Spanish workers reported that the workers with more unstable employment status had a lower level of mental health [scores of 3 or higher on the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) that measures depression and anxiety]. It was found that while 5.6% of full-time male workers suffered from depression, the rate was 26.7% among those employed without a contract. Similarly, 12.5% of full-time female workers suffered from depression, but the rate was 32.5% for women without a full-time contract.

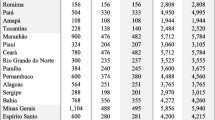

While there have been few studies in non-western countries that examine the relation between depression and SES, those studies have shown similar associations between depression and lower SES. According to a study based on the National Family Research of Japan survey in 1999 [13] that used a nationwide sample (6985 participants aged between 28 and 78 years), although no relation was found between depression and years of education, those from lower household income groups scored significantly higher on depression on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) . In a Japanese study conducted in 2003 [14] with 32,891 senior citizens, it was found that while 17.4% of males with less than 6 years of education were categorized as being in a depressive state (a score of 10 or higher on the GDS-15) , this was the case for only 5.4% of those with 13 or more years of education; approximately a threefold difference. Furthermore, the rate of depression among males from the lowest income group was 15.8%, while that in the highest income group for males was 2.3%, which is a difference between the two groups of 6.9 times. Regional variations were also observed in the prevalence of depression in this study because higher rates of depression were identified in economically disadvantaged rural areas [3]. In their study from 2006, Kawakami et al. [15] used the occupational hierarchy of the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) [16] to show that the risk of being in a depressive state (a score of 16 points or higher on the CES-D) increased 1.05 times for males and 1.13 times for females for each step down in the occupational hierarchy levels. ISCO is an eight-level ranking of employment ranging from managerial positions at the top level to physical labor at the bottom level; the classification is based on the educational and skill levels required for each particular occupation.

3 Background of Inequalities

There are two hypotheses as to how inequalities in terms of SES are related to depression: social causation and social selection. The social causation hypothesis states that various stress factors related to lower SES, such as illness or unemployment, would lead to depression. The social selection hypothesis, in contrast, refers to the idea that those who are susceptible to suffering from depression to begin with (i.e., genetic vulnerability owing to family history related to depressive disorders) fall behind in society, which finally results in lower SES [17].

A British study [18] aimed to verify the social causation and social selection hypotheses by following 756 children of depressive patients for 17 years. The study showed that low parental education was related to increased risk of developing depression among the children. Furthermore, neither the parents’ nor the children’s depression was related to the children’s future SES, such as income, educational level, and occupation. Thus, the results did not support the social selection hypothesis, which argues that suffering from depression will lead to a lower SES. A study [19] of 1803 American adolescents aged 18–23 years, found that adverse experiences such as long-term unemployment and divorce of their parents, unintended separation from parents, separation from one’s own children (including stillbirth), life-threatening accidents and illnesses, betrayal from one’s spouse, suicide or murder of one’s acquaintance, various forms of abuse, and being exposed to a robbery were related to the development of clinical depression and anxiety disorder. These adverse experiences were found to be more prevalent among the lower socioeconomic groups. This association was even more prominent if the subject had suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, drug addiction, and/or behavioral disorders in the past. Adverse experiences in childhood and being physically vulnerable at birth were also correlated with the development of mood disorders [11].

With regard to depression, the sense of control is also an important issue to consider. A state in which one’s sense of control over a situation is deprived creates a feeling of helplessness, which increases the risk of developing depression [20]. It has been reported that when dogs are put in a situation in which they are being given electric shocks, with no means to escape from the shocks or to stop them, the dogs gradually become lethargic and do not attempt to escape even when they are given a chance to do so later. Subsequently, it was discovered that a depressed state could be artificially created in people as well, by depriving them of control [20]. The formation of such a sense of helplessness is perhaps one of the reasons that the rate of depression is higher among people with lower SES, because depression is strongly related to adverse experiences from one’s birth onward. Such adverse experiences are frequently characterized by a lack of control over the events.

Although 33%–48% of the incidences of depression may be explained by genetic vulnerability, over half of the remaining depression cases are found to be caused by factors other than genetics [21]. This means that not only genetics but also the social environment, such as one’s home, workplace, and region of residence, are important. The high prevalence of depression among workers from lower occupational levels may be related to the high job demands (i.e., quantity and quality of work) and the low level of control they are able to exert (e.g., the extent to which they can determine their work method based on their own judgement) [11, 12]. A study [6] conducted in Japan that examined workplace conditions found that poor communication between co-workers and a lack of opportunities for training or promotion were related to an increase in mental disorders among workers. Furthermore, a Danish longitudinal study [22] of 4133 workers found that a low level of control at the workplace, a lack of support from managers, and an unstable employment situation were significantly related to the onset of a depressive state within the following 5 years. Depressive symptoms were measured using the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), a widely used quality-of-life scale. A similar correlation was also reported in the Whitehall II study [11]. The findings from the above-mentioned studies suggest that a lower SES increases an individual’s susceptibility to falling into a state in which the sense of control has been taken away or denied, which, subsequently, could lead to the development of depression. Thus, this pattern could be considered a valid explanation of the inequalities in SES with regard to depression.

4 Possible Countermeasures

As discussed above, depressive states and depression are more frequent among people with low SES, and the development of depression is influenced not only by individual factors but by one’s surrounding environment as well. There is no doubt that expansion of the knowledge on depression and early detection and treatment of depression are necessary [1]. According to the life course approach, which focuses on the impact of the environment during infancy on health during adulthood [11], an enhancement of health and welfare services is required to prevent depression in the socially vulnerable (i.e., the poor). Moreover, educational institutions, from preschool to university education, should take caution not to induce disadvantages for students based on differences in income. Hence, the coordination of related organizations, such as welfare, educational, or medical organizations, and the cooperation of local societies are indispensable.

Measures to prevent depression at the workplace are also crucial. As mentioned above, lower levels of control facilitate the development of depression [20]. Thus, there may be some merit in providing opportunities for workers to become involved in decision making. Furthermore, given that lack of support and unstable employment are predictive factors of depression, support at the workplace (i.e., appropriate work management and hiring external experts) and improvements in working conditions, including compensation and holidays, are also important.

In considering the topic of depression, natural disaster victims cannot be overlooked, because adverse life experiences are strongly associated with this disorder [12]. Recent evidence [23] from Japan demonstrated that group exercise reduced depressive symptoms among survivors of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Although the authors did not specify the type of group activities used, they reported that peer social support or enjoyment were found to mitigate the worsening depression symptoms. This study result indicates that promoting participation in such activities for those at risk of depression is a worthwhile approach. Another study [24] demonstrated that lower socioeconomic gradients of depression are observed among the senior members of communities that are rich in social capital and foster social activities.

5 Summary

Research in western as well as non-western nations has reported that depression is common among people with lower SES, resulting in health inequalities, particularly among those with lower income, lower education, and low-paid occupations [11]. Individuals with fewer years of education and low income are more susceptible to suffering from depression, while an unprivileged environment during childhood increases the likelihood of developing depression during adulthood [4]. Measures against depression often tend to focus on an individual’s genetic predisposition or are otherwise reduced to focus only on the individual. However, in addition to individual predisposition, adverse experiences also relate to depression. Furthermore, countermeasures for unstable employment and employment support for youths are essential. Given the impact that the social environment has on individual health, the discussion on countermeasures for depression should be widened to also focus on social environment factors.

References

World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates; 2017.

Wada T, Ishine M, Sakagami T, et al. Depression in Japanese community-dwelling elderly—prevalence and association with ADL and QOL. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2004;39(1):15–23.

Kondō K. Health inequalities in Japan: an empirical study of older people. Trans Pacific Press, Balwyn North; 2010.

Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, Ansseau M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(2):98–112.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–105.

Japan Productivity Center. The 8th corporate survey research result on “Initiatives on mental health” [In Japanese]. 2017. https://activity.jpc-net.jp/activity_detail.php. Accessed 14 June 2018.

Rugulies R. Depression as a predictor for coronary heart disease: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23(1):51–61.

Stuck AE, Walthert JM, Nikolaus T, Bula CJ, Hohmann C, Beck JC. Risk factors for functional status decline in community-living elderly people: a systematic literature review. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48(4):445–69.

Bennett S, Thomas AJ. Depression and dementia: cause, consequence or coincidence? Maturitas. 2014;79(2):184–90.

GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–59.

Marmot MG. Status syndrome: how your social standing directly affects your health. London: Bloomsbury; 2005.

Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Final report. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

Inaba A, Thoits PA, Ueno K, Gove WR, Evenson RJ, Sloan M. Depression in the United States and Japan: gender, marital status, and SES patterns. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(11):2280–92.

Murata C, Kondo K, Hirai H, Ichida Y, Ojima T. Association between depression and socio-economic status among community-dwelling elderly in Japan: the Aichi Gerontological Evaluation Study (AGES). Health Place. 2008;14(3):406–14.

Kawakami N, Takao S, Kobayashi Y, Tsutsumi A. Effects of web-based supervisor training on job stressors and psychological distress among workers: a workplace-based randomized controlled trial. J Occup Health. 2006;48(1):28–34.

Goldberg D, Williams P. A user’s guide to the general health questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-NELSON; 1988.

Costello EJ, Compton SN, Keeler G, Angold A. Relationships between poverty and psychopathology: a natural experiment. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2023–9.

Ritsher JEB, Warner V, Johnson JG, Dohrenwend BP. Inter-generational longitudinal study of social class and depression: a test of social causation and social selection models. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178(S40):84–90.

Turner RJ, Lloyd DA. Stress burden and the lifetime incidence of psychiatric disorder in young adults: racial and ethnic contrasts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(5):481–8.

Reivich K, Gillham JE, Chaplin TM, Seligman MEP. From helplessness to optimism: the role of resilience in treating and preventing depression in youth. In: Goldstein S, Brooks RB, editors. Handbook of resilience in children. Boston, MA: Springer; 2013. p. 201–14.

Hill MK, Sahhar M. Genetic counselling for psychiatric disorders. Med J Aust. 2006;185(9):507–10.

Rugulies R, Bultmann U, Aust B, Burr H. Psychosocial work environment and incidence of severe depressive symptoms: prospective findings from a 5-year follow-up of the Danish work environment cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(10):877–87.

Tsuji T, Sasaki Y, Matsuyama Y, et al. Reducing depressive symptoms after the great East Japan earthquake in older survivors through group exercise participation and regular walking: a prospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):e013706.

Haseda M, Kondo N, Ashida T, Tani Y, Takagi D, Kondo K. Community social capital, built environment, and income-based inequality in depressive symptoms among older people in Japan: an ecological study from the JAGES project. J Epidemiol. 2018;28(3):108–16.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this chapter or parts of it.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Murata, C., Kondo, K. (2020). Depression. In: Kondo, K. (eds) Social Determinants of Health in Non-communicable Diseases. Springer Series on Epidemiology and Public Health. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1831-7_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1831-7_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-1830-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-1831-7

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)