Abstract

In perennial woody plants, dormancy-induced alteration of potassium (K) localization is assumed one of the mechanisms for adapting and surviving the severe winter environment. To establish if radio-cesium (137Cs) localization is also affected by dormancy initiation, the artificial annual environmental cycle was applied to the model tree poplar. Under the short day-length condition, the amount of 137Cs in shoots absorbed through the roots was drastically suppressed, but the amount of 42K was unchanged. Potassium uptake from the rhizosphere is mainly mediated by KUP/HAK/KT and CNGC transporters. However, in poplar, these genes were constantly expressed under the short-day condition and there were no up- or down-regulation. These results indicated the suppression of 137Cs uptake was triggered by the short-day length, however, the key transporter and the mechanism remains unclear. We hypothesized that Cs and K transport systems are separately regulated in poplar.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

10.1 Introduction

In 2011, radionuclides were released into the environment due to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. Among the released radionuclides, radio-cesium (137Cs) has been considered the main environmental contaminant. A large part of the contaminated land was forested and, after the accident, the 137Cs deposition to tree canopies, uptake through leaves and/or bark, and the translocation to growing branch were actively investigated (Kato et al. 2012; Takata 2013; Kanasashi et al. 2015). However, 137Cs uptake from the contaminated soil through the root was not well investigated because of methodological challenges. Therefore, the physiological knowledge of Cs transfer from the soil and its distribution among the tree organs is limited.

Cesium has a chemical property similar to potassium (K), but it is not an essential nutrient for plants. Generally, the rhizosphere Cs concentration (almost all is stable 133Cs) is less than approx. 200 μM and not toxic to plant growth (White and Broadley 2000). Cesium uptake and translocation within the plant body are considered to be mediated by K+ transport systems (White and Broadley 2000). Arabidopsis HAK5 (AtHAK5) is one of the best investigated root K+ uptake transporters, and its mutant, athak5, showed a tolerance against 300 μM Cs treatment under low K conditions (Ahn et al. 2004; Gierth et al. 2005; Qi et al. 2008). AtCNGCs are Voltage-Independent Cation Channels (VICCs) type K+ permeable channels and AtCNGC1 is the candidate gene for Cs uptake identified by quantitative trait locus analysis in Arabidopsis (Leng et al. 1999; Kanter et al. 2010).

To understand 137Cs behavior within woody plants, Cs content in each organ should be revealed under each seasonal environment, because K distribution among tree organs is changed by the seasonal transition. To combine the seasonal change of Cs distribution and the genetic information related to Cs transport, we used poplar as an experimental plant, although it is not the major tree species in the Fukushima region. Poplar is a perennial deciduous tree and the seasonal cycle of growth and dormancy is distinct. The genome of Populus trichocarpa is available (Tuskan et al. 2006) and the findings related to the Cs and K transport mechanisms obtained from crop research are applicable. Moreover, the high transfer rate of Cs from soil to poplar leaves has been observed under 137Cs contaminated regions in Europe (International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) 2010).

In trees, the phase shift from growth to dormancy is a basic winter adaptation mechanism (Jansson et al. 2010) and the transition of meristems into dormant buds is crucial for cold adaptation to protect the meristems against hazardous frosts. By perceiving the change in photoperiod and temperature, woody plants can shift their growth stage (Welling et al. 2002), and the initiation of cold acclimation under the short-day length increases endogenous abscisic acid levels and reduces endogenous gibberellic acid levels (Olsen et al. 1997; Welling et al. 1997; Mølmann et al. 2005). In beech (Fagus sylvatica L.), leaf K content is rapidly decreased before shedding and the retrieved K is deposited in the cortex and pith tissues of the stem (Eschrich et al. 1988). Japanese native poplar (Populus maximowiczii) can decrease leaf K concentration after dormant bud formation (Furukawa et al. 2012). In addition, the increase of K concentration in xylem sap was observed during the winter period in field grown Populus nigra (Furukawa et al. 2011). These K behaviors implied the existence of a re-translocation mechanism and it is assumed that K and Cs are transported to K required organs for growth regulation and/or survival.

In this chapter, we will outline the experimental method of the artificial annual environmental cycle for cultivating small scale sterilized poplar and the investigation of 137Cs and 42K uptake through their roots under long and short photoperiod conditions.

10.2 Application of the Artificial Annual Environmental Cycle to Poplar

In poplar, dormancy is primarily initiated in response to short-day lengths (Sylven 1940; Nitsch 1957), and the recent genetic and physiological understandings of dormancy initiation and break make poplar a highly suitable model tree for investigating growth rhythms. And the Populus trichocarpa genome was sequenced and expressed sequence tags of Populus were also identified (Kohler et al. 2003; Sterky et al. 2004). To utilize these advantages, we used poplar Hybrid aspen T89 (Populus tremula x tremuloides) as our experimental plants for investigating the shift of K and Cs distribution.

Hybrid aspen T89 were cultured in half-strength Murashige & Skoog (MS) medium in a sterilized container (height 14 cm, diameter 11 cm) (Fig. 10.1a) under light- and temperature-controlled conditions; 16 h light (light intensity 37.5 μmol m−1 s−1) and 8 h dark cycle, 23 °C (Fig. 10.1b). Once a month, each plant was cut approx. 5 cm below the shoot apex and replanted in a container containing new MS medium under sterile conditions.

The annual cycle of poplar growth is re-created in the artificial annual environmental cycle, which is a modification of a similar method by Kurita et al. (2014). The poplar was treated with three stages: Stage-1 (Spring and Summer) 23 °C, 16 h light /8 h dark, Stage-2 (Autumn) 23 °C, 8 h light/16 h dark and Stage-3 (Winter) 4 °C, 8 h light/16 h dark (Table 10.1). Poplars can break its dormant bud after the return to Stage-1 within 2 weeks. In our artificial annual environmental cycle, in contrast to Kurita et al. (2014), the temperature in Stage-2 was set to 23 °C. Our preliminary experiments revealed that the dormant bud formation can be triggered by 4 weeks of short day-length treatment when the temperature is less than 23 °C. To minimize the environmental factors related to the dormancy initiation, the temperature was kept constant in Stage-1 and -2.

10.3 Measurement of 137Cs and 42K Distributions in Poplar

Under the artificial annual environmental cycle using Populus alba L., the shift of growth condition from Long Day (LD) to Short Day (SD) condition decreased the phosphate contents in lower leaves (Kurita et al. 2014). This change of phosphate content suggested the existence of a mechanism for the re-translocation of phosphate from lower leaves to younger upper leaves with seasonal changes. Regarding calcium (Ca) translocation, Furukawa et al. (2012) indicated the Ca transport from root to shoot is also regulated by the shift from LD to SD in Populus maximowiczii. To investigate if a similar shift occurs for 137Cs, Cs uptake through roots and its behavior within the plant body was compared in LD and SD conditions (Noda et al. 2016).

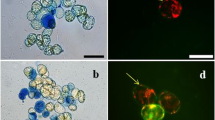

Poplars were grown under Stage-1 (LD) condition for 3 or 9 weeks (LD3 and LD9) in a light- and temperature-controlled environment. For investigating the effect of seasonal transition, a part of the LD3 plants were grown under Stage-2 (SD) conditions for an additional 2, 4 and 6 weeks (SD2, SD4 and SD6). After those cultivations, 137CsCl (25 kBq, with 0.1 μM 133CsCl) or 42K (8 kBq, with 0.1 μM 39KCl) (Aramaki et al. 2015; Kobayashi et al. 2015) solution was added to the growth medium to observe root absorption. Cesium-137 distribution was investigated with the autoradiography technique in LD3, LD9 and SD6 plants and the harvested plants were cut into four parts, apex (shoot apex and top three leaves), leaf (remaining leaves and petioles), stem and root.

Figure 10.2a displays the localization of 137Cs through root absorption under LD3, LD9 and SD6 conditions. In LD3 plants, 137Cs was localized entirely and the radiation intensity around the apex was higher than other organs. Similarly, LD9 which was the same age as SD6 plants and grown under LD condition also showed the same 137Cs behavior as LD3 plants. In SD6 plants, 137Cs was mainly localized in the stem and root, furthermore, the total 137Cs quantity seemed to have decreased. Comparing 137Cs in the shoot (all shoot organs) and root under LD3, LD9 and SD6, the quantity of 137Cs in shoots under SD6 condition was the lowest (Fig. 10.2b). However, 137Cs quantity in roots was similar under each condition.

Effect of short-day (SD) transition for 137Cs uptake activity in poplar. (a) Cesium-137 localization through root application under long-day (LD) conditions (LD3, LD9 and SD6). Upper images are photo and lower images indicate autoradiograph. Poplars were treated with 137Cs for 48 h. The color change from blue to red indicates 137Cs accumulation in autoradiography imaging. Bar = 1 cm. (b) Alteration of total amounts of 137Cs in poplar with SD transition. Poplars in each condition were treated with 137Cs for 48 h. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). [Modified from Noda et al. (2016)]

In respect to the amount of 137Cs in each organ, 137Cs mainly accumulated in leaves under LD3 condition (48.8% of applied 137Cs) (Fig. 10.3a); in the LD9 condition, accumulation pattern was similar to LD3. However, under SD6 condition, leaf 137Cs content was the second highest (32.1%) and 137Cs mostly accumulated in the stem (39.7%). As for the 137Cs concentration, the effect of SD transition on 137Cs distribution mainly resulted in suppressing Cs transport into shoot apices and leaves (Fig. 10.3b).

Detailed 137Cs accumulation patterns under different growth condition. Poplars were separated into apices (including upper three leaves), leaves, stem and roots. (a) Detailed 137Cs accumulation in each organ after 48 h treatment under long-day (LD) and short-day conditions (SD) (LD3, LD9 and SD6). (b) Cesium-137 concentrations in each organ after 48 h treatment under LD3, LD9 and SD6 conditions. Three plants were tested for each condition. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). [Modified from Noda et al. (2016)]

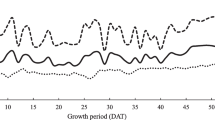

From the result of 137Cs uptake assays, it was expected that the amount of 42K absorbed through the root was also down-regulated by SD transition. To explain the K uptake activity with seasonal change, poplar was treated with exogenous 42K application to the root and the quantity of K in shoot and root under LD3, SD2, SD4 and SD6 conditions were measured after 24 h incubation (Fig. 10.4). Contrary to our expectations, there was no difference in the amount of 42K in either root or shoot among the four conditions. These data suggest that the K demand for the rhizosphere was not changed by SD transition in poplar up to 6 weeks.

Effect of short-day (SD) transition for 42K uptake activity in poplar. Total amount of 42K in poplar shoot and root with SD transition. 42K under each condition was treated for 24 h. Three plants were tested for each condition. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). (Modified from Noda et al. (2016))

Comparing the data presented in Figs. 10.2 and 10.4, 137Cs accumulation decreased under SD6 condition but 42K accumulation remained constant through the SD transition. This inconsistency suggests that Cs accumulation might be separately controlled, and not part of the major K uptake systems in poplar. In addition, it is also implied that the responsible transporter for poplar Cs uptake might be poorly involved in K uptake because no decrease of K accumulation was observed under the low Cs accumulation condition.

10.4 Expression of Potassium Influx Transporters in Poplar Root

To identify the Cs uptake responsible transporter, we investigated the expression patterns of some candidate genes under SD condition. Among various K+ uptake transporters, we focused on high-affinity K+ transporters, KUP/HAK/KT family (Rubio et al. 2000; Mäser et al. 2001; Gupta et al. 2008), and low-affinity channel, cyclic-nucleotide-gated channel (CNGC) (Hua et al. 2003; Harada and Leigh 2006; Ahmad and Maathuis 2014). As for one of the KUP/HAK/KT family genes, we focused on Populus tremula K+ uptake transporter 1, PtKUP1 (POPTR_0003s13370), identified from hybrid aspen. PtKUP1 was used for the complementation test using K uptake-deficient E. coli mutant. The addition of toxic level Cs to the culture media inhibited the growth of E. coli expressing PtKUP1 strongly, suggesting PtKUP1 can transport both K and Cs (Langer et al. 2002). In addition to PtKUP1, there are eight AtHAK5 orthologue genes in Populus trichocarpa. Arabidopsis HAK5 (AtHAK5) is a well-known root K+ uptake transporter and it has been reported that the induction of AtHAK5 is enhanced by K+ deficiency (Ahn et al. 2004; Gierth et al. 2005) or by Cs+ applications when there is sufficient K+ (Adams et al. 2013). Based on the similarity of those nine putative KUP/HAK/KT family K+ transporters, POPTR_0010s10450 and POPTR_0001s00580 were chosen as highly homologous genes with AtHAK5. We identified POPTR_0010s10450 and POPTR_0001s00580 homologues in hybrid aspen T89 and named those Populus tremula x tremuloides HAK-like1 (PttHAK-like1) and PttHAK-like2, respectively. Similar to HAK-like genes, two CNGC-like genes were selected from nine AtCNGC1 homologue genes in P. trichocarpa. POPTR_0012s01690 and POPTR_0015s02090 had a higher similarity to ATCNGC1 and those homologues in hybrid aspen T89 were named PttCNGC1-like1 and PttCNGC1-like2, respectively.

The expression patterns of these genes were measured during the transition to the SD condition (Fig. 10.5). There was no significant change in PtKUP1 expression. PttHAK-like1 showed steady expression until SD4 condition and was slightly up-regulated by about 1.5-fold under SD6 condition. PttHAK-like2 exhibited the decreasing tendency in SD2 and SD4 plants, but remained statistically constant through the SD transition. Two PttCNGC1-like genes also expressed relatively constantly under SD condition.

Effect of short-day (SD) transition on transcriptional expression of HAK and CNGC orthologue genes in poplar root. Total RNA was isolated from root and these gene transcript levels were analyzed by qRT-PCR. UBIQUTIN was used as the reference gene. All gene expression levels were normalized by expression level of LD3 condition. Error bars represent standard deviation. * indicated significant difference to the level of LD3 expression level (* <0.01). (Modified from Noda et al. (2016))

In this experimental condition, dormant buds were formed up to 4 weeks after starting the short-day treatment and, therefore, the re-translocation of K should have already commenced at SD6. However, the results showed that the 42K accumulation through root uptake and gene expression related to the root K uptake were almost constant. Steady-state of K requirement under SD condition seems to indicate abundant K was stored in the plant body and the change of K demand might be covered by the internal re-translocation.

10.5 Perspectives in Cs+ Transporter Research

Despite the constant K accumulation patterns under SD conditions, Cs accumulation was drastically decreased in SD6 plant (Figs. 10.2 and 10.4). Cesium uptake and translocation is considered to be regulated by plant K transport system, however, no down-regulation in candidate genes was observed at SD6 (Fig. 10.5). However, it is not known if elemental transport is only regulated by gene expression and not by protein activity (White and Broadley 2000). But the inconsistence of 42K+ and 137Cs+ localization patterns indicates a possible existence of an unknown Cs uptake system which preferentially transports Cs rather than K.

Based on our experimental design to identify permeable Cs transporters, it would appear that the mechanisms regulating the specificity of these transporters are very complex and it might be difficult to identify the responsible genes through reverse genetics. Our studies have also demonstrated that Cs uptake in poplar is regulated by the photoperiod, therefore, the mechanisms of the dormancy initiation might be involved in the suppression of Cs uptake. Using our data and the increasing knowledge of dormancy, the mechanisms of Cs uptake from contaminated soil to forest trees should be revealed and we hope that the understanding of Cs circulation within the forest ecosystem will be utilized in the prediction of Cs transfer among the terrestrial environment in the near future.

References

Adams E, Abdollahi P, Shin R (2013) Cesium inhibits plant growth through jasmonate signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Mol Sci 14:4545–4559

Ahmad I, Maathuis FJM (2014) Cellular and tissue distribution of potassium: physiological relevance, mechanisms and regulation. J Plant Physiol 171:708–714

Ahn SJ, Shin R, Schachtman DP (2004) Expression of KT/KUP genes in Arabidopsis and the role of root hairs in K+ uptake. Plant Physiol 134:1135–1145

Aramaki T, Sugita R, Hirose A, Kobayashi NI, Tanoi K, Nakanishi TM (2015) Application of 42K to Arabidopsis tissues using real-time radioisotope imaging system (RRIS). Radioisotopes 64:169–176

Eschrich W, Fromm J, Essiamah S (1988) Mineral partitioning in the phloem during autumn senescence of beech leaves. Trees 2:73–83

Furukawa J, Abe Y, Mizuno H, Matsuki K, Sagawa K, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Iwai H, Satoh S (2011) Seasonal fluctuation of organic and inorganic components in xylem sap of Populus nigra. Plant Root 5:56–62

Furukawa J, Kanazawa M, Satoh S (2012) Dormancy-induced temporal up-regulation of root activity in calcium translocation to shoot in Populus maximowiczii. Plant Root 6:10–18

Gierth M, Mäser P, Schroeder JI (2005) The potassium transporter AtHAK5 functions in K+ deprivation-induced high-affinity K+ uptake and AKT1 K+ channel contribution to K+ uptake kinetics in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Physiol 137:1105–1114

Gupta M, Qiu X, Wang L, Xie W, Zhang C, Xiong L, Lian X, Zhang Q (2008) KT/HAK/KUP potassium transporters gene family and their whole life cycle expression profile in rice (Oryza sativa). Mol Gen Genomics 280:437–452

Harada H, Leigh RA (2006) Genetic mapping of natural variation in potassium concentrations in shoots of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot 57:953–960

Hua BG, Mercier RW, Leng Q, Berkowitz GA (2003) Plants do it differently. A new basis for potassium/sodium selectivity in the pore of an ion channel. Plant Physiol 132:1353–1361

Jansson S, Bhalerao RP, Groover AT (2010) Genetics and genomics of populus. Springer, New York

Kanasashi T, Sugiura Y, Takenaka C, Hijii N, Umemura M (2015) Radiocesium distribution in sugi (Cryptomeria japonica) in eastern Japan: translocation from needles to pollen. J Environ Radioact 139:398–406

Kanter U, Hauser A, Michalke B, Dräxl S, Schäffner AR (2010) Cesium and strontium accumulation in shoots of Arabidopsis thaliana: genetic and physiological aspects. J Exp Bot 61:3995–4009

Kato H, Onda Y, Gomi T (2012) Interception of the Fukushima reactor accident-derived 137Cs, 134Cs, and 131I by coniferous forest canopies. Geophys Res Lett 39. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL052928.

Kobayashi NI, Sugita R, Nobori T, Tanoi K, Nakanishi TM (2015) Tracer experiment using 42K+ and 137Cs+ revealed the different transport rates of potassium and caesium within rice roots. Funct Plant Biol 43:151–160

Kohler A, Delaruelle C, Martin D, Encelot N, Martin F (2003) The poplar root transcriptome: analysis of 7000 expressed sequence tags. FEBS Lett 542:37–41

Kurita Y, Baba K, Ohnishi M, Anegawa A, Shichijo C, Kosuge K, Fukaki H, Mimura T (2014) Establishment of a shortened annual cycle system; a tool for the analysis of annual re-translocation of phosphorus in the deciduous woody plant (Populus alba L.). J Plant Res 127:545–551

Langer K, Ache P, Geiger D, Stinzing A, Arend M, Wind C, Regan S, Fromm J, Hedrich R (2002) Poplar potassium transporters capable of controlling K+ homeostasis and K+-dependent xylogenesis. Plant J 32:997–1009

Leng Q, Mercier RW, Yao W, Berkowitz GA (1999) Cloning and first functional characterization of a plant cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channel. Plant Physiol 121:753–761

Mäser P, Thomine S, Schroeder JI, Ward JM, Hirschi K, Sze H, Talke IN, Amtmann A, Maathuis FJ, Sanders D, Harper JF, Tchieu J, Gribskov M, Persans MW, Salt DE, Kim SA, Guerinot ML (2001) Phylogenetic relationships within cation transporter families of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 126:1646–1667

Mølmann JA, Asante DKA, Jensen JB, Krane MN, Ernstsen A, Junttila O, Olsen JE (2005) Low night temperature and inhibition of gibberellin biosynthesis override phytochrome action and induce bud set and cold acclimation, but not dormancy, in PHYA overexpressors and wild-type of hybrid aspen. Plant Cell Environ 28:1579–1588

Nitsch JP (1957) Growth responses of woody plants to photoperiodic stimuli. Proc Am Soc Hortic Sci 70:512–525

Noda Y, Furukawa J, Aohara T, Nihei N, Hirose A, Tanoi K, Nakanishi TM, Satoh S (2016) Short day length-induced decrease of cesium uptake without altering potassium uptake manner in poplar. Sci Rep 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep38360

Olsen JE, Junttila O, Nilsen J, Eriksson ME, Martinussen I, Olsen O, Sandberg G, Moritz T (1997) Ectopic expression of oat phytochrome A in hybrid aspen changes critical day length for growth and prevents cold acclimatization. Plant J 12:1339–1350

Qi Z, Hampton CR, Shin R, Barkla BJ, White PJ, Schachtman DP (2008) The high affinity K+ transporter AtHAK5 plays a physiological role in planta at very low K+ concentrations and provides a cesium uptake pathway in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot 59:595–607

Rubio F, Santa-Maria GE, Rodriguez-Navarro A (2000) Cloning of Arabidopsis and barley cDNAs encoding HAK potassium transporters in root and shoot cells. Physiol Plant 109:34–43

Sterky F, Bhalerao RR, Unneberg P, Segerman B, Nilsson P, Brunner AM, Charbonnel-Campaa L, Lindvall JJ, Tandre K, Strauss SH, Sundberg B, Gustafsson P, Uhlén M, Bhalerao RP, Nilsson O, Sandberg G, Karlsson J, Lundeberg J, Jansson S (2004) A Populus EST resource for plant functional genomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:13951–13956

Sylven N (1940) Lang-och kortkagstyper av de svenska skogstraden [Long day and short day types of Swedish forest trees]. Svensk Papperstidn 43:317–324, 332–342, 350–354

Takata D (2013) Distribution of radiocesium from the radioactive fallout in fruit trees. In: Nakanishi TM, Tanoi K (eds) Agricultural implications of the Fukushima nuclear accident. Springer, New York, pp 143–162

International Atomic Energy Agency (2010) Handbook of parameter values for the prediction of radionuclide transfer in terrestrial and freshwater environments, Technical report series No. 472, vol 472. International Atomic Energy Agency, Vienna, pp 99–108

Tuskan GA, DiFazio S, Jansson S, Bohlmann J, Grigoriev I, Hellsten U, Putnam N, Ralph S, Rombauts S, Salamov A, Schein J, Sterck L, Aerts A, Bhalerao RR, Bhalerao RP, Blaudez D, Boerjan W, Brun A, Brunner A, Busov V, Campbell M, Carlson J, Chalot M, Chapman J, Chen GL, Cooper D, Coutinho PM, Couturier J, Covert S, Cronk Q, Cunningham R, Davis J, Degroeve S, Déjardin A, dePamphilis C, Detter J, Dirks B, Dubchak I, Duplessis S, Ehlting J, Ellis B, Gendler K, Goodstein D, Gribskov M, Grimwood J, Groover A, Gunter L, Hamberger B, Heinze B, Helariutta Y, Henrissat B, Holligan D, Holt R, Huang W, Islam-Faridi N, Jones S, Jones-Rhoades M, Jorgensen R, Joshi C, Kangasjärvi J, Karlsson J, Kelleher C, Kirkpatrick R, Kirst M, Kohler A, Kalluri U, Larimer F, Leebens-Mack J, Leplé JC, Locascio P, Lou Y, Lucas S, Martin F, Montanini B, Napoli C, Nelson DR, Nelson C, Nieminen K, Nilsson O, Pereda V, Peter G, Philippe R, Pilate G, Poliakov A, Razumovskaya J, Richardson P, Rinaldi C, Ritland K, Rouze P, Ryaboy D, Schmutz J, Schrader J, Segerman B, Shin H, Siddiqui A, Sterky F, Terry A, Tsai CJ, Uberbacher E, Unneberg P, Vahala J, Wall K, Wessler S, Yang G, Yin T, Douglas C, Marra M, Sandberg G, Van de Peer Y, Rokhsar D (2006) The genome of black cottonwood, Populus trichocarpa (Torr. & Gray). Science 313:1596–1604

Welling A, Kaikuranta P, Rinne P (1997) Photoperiodic induction of dormancy and freezing tolerance in Betula pubescens. Involvement of ABA and dehydrins. Physiol Plant 100:119–125

Welling A, Moritz T, Palva ET, Junttila O (2002) Independent activation of cold acclimation by low temperature and short photoperiod in hybrid aspen. Plant Physiol 129:1633–1641

White PJ, Broadley MR (2000) Mechanisms of cesium uptake by plants. New Phytol 147:241–256

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Noda, Y., Aohara, T., Satoh, S., Furukawa, J. (2019). Application of the Artificial Annual Environmental Cycle and Dormancy-Induced Suppression of Cesium Uptake in Poplar. In: Nakanishi, T., O`Brien, M., Tanoi, K. (eds) Agricultural Implications of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident (III). Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3218-0_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3218-0_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-3217-3

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-3218-0

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)