Abstract

Internal migration in Indonesia has officially been recognized since 1930 when the country was still a Dutch colony (World Population Year 1974). It was historically a kind of forced migration initiated to redistribute the population over the country—that is, a form of transmigration (Hugo 2004). The government then had a programme to shift the population from the most densely inhabited area of Java to other less populated islands to improve the overall welfare of the ‘transmigrants’ as most of them were poor farmers. During the later decades, more and more people have been migrating voluntarily across areas in the country. This is a result of the massive restructuring and transformation of the economy as well as for other reasons.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Internal migration

- Current and return migrant

- Individual and family migrant

- Distance and urban-rural

- Poverty

- Panel data

- Indonesia

1 Introduction

Internal migration in Indonesia has officially been recognized since 1930, when the country was still a Dutch colony (World Population Year 1974)Footnote 1. It was historically a kind of forced migration initiated to redistribute the population over the country—that is, a form of transmigration (Hugo 2004). The government then had a programme to shift the population from the most densely inhabited areas of Java to other, less populated islands to improve the overall welfare of the ‘transmigrants’ as most of them were poor farmers. During the later decades, more and more people have been migrating voluntarily across areas in the country. This is a result of the massive restructuring and transformation of the economy as well as for other reasons.

As far as studies on internal migration are concerned, there have been very few due to the lack of data that can be used to study the issue comprehensively, among other reasons (McNicoll 1968; World Population Year 1974; Hugo 1982). This is partly because of the complexity involved in defining internal migration and the lack of migration data in the existing statistical system. The former is reflected from the fact that many authors have used different administrative boundaries to define migration such as district or province while the latter is evident from the fact that there is no systematic and consistent migration data collection effort at different administration levels. The problem is made worse by the dynamics of internal administration boundaries that keep changing following the changes in the administration boundaries of provinces, districts, subdistricts and villages as a result of their increasing numbers and changes in the extent of area development and decentralization. Many areas of villages, districts and provinces were merged, split or expanded during the period concerned (BPS http://www.bps.go.id).

This chapter tries to address a key issue related to the link between internal migration and poverty reduction. The two are complex issues, and therefore their links would be complex too. In general, internal migration can reduce or increase poverty for the origins and destinations. From the household perspective, internal migration can be a way for the poor to escape poverty through direct participation in the migration as well as from the effects of remittances to migrant and non-migrant households.

Given the nature of the panel data set used in the study, migration can be further classified into current and return migration to reflect the migration cycle issue. The current migrant is further grouped into ‘away’ and ‘staying’ within the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS) sampled households. On the basis of how migrants move, the migration can be classified into individual and whole family migrations , while in terms of distance covered, it is grouped into within district, within province and across province. Furthermore, the areas of origin and destination can be classified as rural or urban. The main reasons for migration are examined as well as the characteristics of the migrants themselves. All these aspects are directly related to the literature on (internal) migration, highlighting the important roles of the migration cycle, distance, areas and other characteristics, and are essential for understanding the link between internal migration and the poverty situation.

Therefore, this research contributes to the internal migration literature by analysing the issue and putting it in the context of whether the migration is done individually or with the whole family, the distance covered, the origin and destination areas of urban and rural and in relation to the main reasons for migration. All these factors are linked to the migrants’ poverty conditions before and after the migration. Moreover, the chapter considers other characteristics of migrants and their households to further shed light on how internal migration contributes to poverty reduction. The results from analysing the key dynamic factors driving different forms and patterns of internal migration in helping reduce poverty is not only an interesting topic but also have relevant and timely policy implications.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides the context of internal migration and poverty in Indonesia. Section 3 describes the data and concept of internal migration used in this research. Section 4 provides the methodology. Section 5 presents the results and analysis while the last section summarizes the findings and provides their policy implications.

2 The Context of Internal Migration and Poverty

Theoretically, migration is a spatial issue involving change in the residential place from the origin to the destination area. In terms of administrative boundaries, this could be within a district, within a province and across provinces. In terms of time, migration could occur over a given period of time such as a lifetime, 5 years or any other specific time interval.Footnote 2 In this context, a migration analysis attempts to explain the causes and/or consequences of migration in the context of answering key questions, such as who migrates, why, where, when and what are the consequences of migration, including in terms of poverty reduction. This is an important issue given that Indonesia, with more than 17,000 islands and a 245 million population, still has a relatively high percentage of poor people, and the geographical condition of the country has created a remarkable difference in poverty levels. The eastern part of the archipelago is relatively less developed than the western part, and this contributes to the main factors that influence people to move. Indonesia is also one of the countries that has shown an increasingly high population movement, which needs immediate policy actions, such as improving data and information related to migration, developing social security and financial services for migrants and building (urban and other) infrastructure and human capacities (Deshingkar 2006).

The internal migration examined in this chapter includes the movement of people individually, or as part of the whole family, from rural to urban, rural to rural, urban to rural and urban to urban areas by covering a distance within a district, within a province and across provinces for various different reasons. It has been observed that migrants seek better economic opportunities, particularly in cities and towns (Harris and Speare 1986). Internal migration is a result of a combination of ‘push factors’ from the original place and ‘pull factors’ from the destination areas. In between, there are always barriers to movement. The push factors include economic, demographic, political, social, cultural and environment issues. The pull factors are mostly better economic opportunities in the destination places, such as better employment and standard of living. Empirical studies show that economic factors are more important in driving internal migration in Indonesia (Hugo 2004; Lottum and Marks 2010). Other factors may also contribute to migration such as economic and demographic imbalances resulting from excess demand for some types of labour and ageing in some places, worsening opportunities in traditional/low-yield agriculture and increasing opportunities in urban areas, increasing globalization and the effects of the climate change (The House of Commons 2004).

2.1 Internal Migration in Indonesia

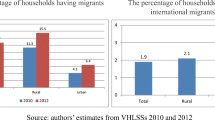

In terms of numbers, internal migration in Indonesia is at a much larger scale than international migration. As the fourth-most populous country in the world, internal migration of all types in Indonesia accounts for about 9% of the population (Lu 2008). The figure is still lower than internal migration in other developing countries, especially in terms of internal migration density relative to population movement (Bell and Muhidin 2009). On the other hand, the share of international migration in Indonesia is estimated as less than 3% of the population.

The transmigration programme initiated during the Dutch colonization is still implemented by the new Indonesian government. The policy basically offers free land, housing, transportation, food and fertilizers as incentives for the inhabitants of the island of Java to migrate to less densely populated areas in Sumatra and the eastern part of Indonesia, such as Papua, Kalimantan and Sulawesi. The transmigration programme was expanded, and in 1980–1990, there were more people resettling in transmigration provinces than before. However, the programme was stopped for a while due to lack of funds following the 1997–1998 Asian financial crisis that hit Indonesia hard (Lottum and Mark 2010). Currently, internal migration in Indonesia is more voluntary in nature, including for those joining the transmigration programme.

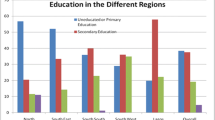

People migrate to different places in search of a better life, such as a higher income and living standard compared to the original place. In this context, distance is still an important factor in influencing migration. Recent research by Deb and Seck (2009) shows that most movement in Indonesia between 1993 and 2000 occurred within the same province, which could be seen as the most favourable distance for work-related opportunities, given that moving to the city brings with it many challenges. They also found that Indonesian households with internal migrants earn less than half of the top two quintiles of households in 1993, but the figure rose to nearly two-thirds of the top two quintiles in 2000. This means that internal migrants are not among the richest and the poorest and their income levels have relatively increased over the period. The study also found that households with more adult members and those in industrial areas are more likely to migrate than those that live in agricultural communities. Internal migrants (both urban and rural) are more likely to live longer and achieve higher education levels than non-migrants. An empirical study shows that internal migrants overall achieve a higher level of human development than non-migrants (Harttgen and Klasen 2009).

On the other hand, internal migration can also contribute to poverty conditions in the destination area in many different ways (Perlman 1976; Rondinelli 1985; Tacoli 2012), such as from a combination of poor and non-poor people moving from the original to the destination place and becoming the new poor in the destination area. With regard to the place of origin, the moving out of the poor and the non-poor can worsen or improve the poverty situation depending on the dynamic links between migrants and non-migrants. Therefore, the interlink between internal migration and poverty is a matter of empirical context, which cannot be predetermined by theory.

2.2 Poverty in Indonesia

Indonesia has experienced significant poverty reduction in urban and rural areas during the three decades before the Asian financial crisis in 1997/1998. This was due to mainly robust economic growth. The crisis, however, caused the poverty rate to increase from 18% in 1996 to 24% in late 1998. About two-thirds of the poor in Indonesia reside in rural areas, so poverty is more of a rural than an urban issue (BPS-Statistics Indonesia) . It is important to note that a person is considered to be poor if her average per capita expenditure per month is below the poverty line, which is defined at the provincial level with the poverty line for urban and rural areas calculated separately.Footnote 3 Therefore, poverty incidence at the provincial level in total is an aggregation of the poverty incidences in the rural and urban areas of the province.

The poverty incidence or headcount ratio from 1996 to 2013 has been declining, ranging between 11% and 24%. As mentioned earlier, the percentage of the poor has decreased every year, except in 1998 and 2006 when the numbers increased due to economic crises. Figure 6.1 shows the declining trend of poverty in Indonesia with the spikes in 1998 due to the Asian financial crisis and in 2006 due to the global financial crisis, both of which hit Indonesia hard. Despite the declining poverty incidence, poverty remains an important issue in Indonesia. For instance, a World Bank study in 2006 showed that 40% of the Indonesian population earned below US$ 2/day, 16.7% earned below US$ 1.5/day (close to the national poverty line ) and 7.4% earned below US$ 1/day. These figures highlight that poverty and low income are still a significant issue in the country.

It is also important to note that the country has experienced a rapid and continued increase in urbanization, which has helped reduce poverty. Poverty reduction in rural areas is higher than in urban areas. More than half of Indonesia’s total population now resides in urban areas while the share of the urban population 20 years ago was only about one-third. Despite the progress, the rural population is still relatively poor. Table 6.1 shows poverty incidences in rural and urban areas over time based on consumption outlays based on the national poverty lineFootnote 4, showing not only a higher poverty incidence but also a faster poverty reduction in rural areas. During the period of 1996–2012, the poverty incidence in rural areas declined from 20% to 15%, a reduction by 5 percentage points, while in urban areas, it declined from 12% to 9%, a reduction of 3 percentage points. This makes sense since the poverty incidence in urban areas is already low, and reducing it further would be difficult.

3 Data and Internal Migration Concept Used

This study is conducted using the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS) panel data in 2000 (IFLS3) and 2007 (IFLS4) from http://www.rand.org/labor/FLS/IFLS.html, which provide detailed information about individuals and households on many different aspects, including internal migration. The address and family relationship of each individual in the household can be traced back over the 7-year period of the two surveys. On the basis of this, information about how migrants move, where they move from/to, the distance covered, are they still away or have they returned and the main reason for the move can all be established. The poverty status of the individual/household before and after the migration can also be determined. Accordingly, the issue of internal migration and its links to poverty reduction can be analysed systematically and comprehensively.

When looking at rural-urban migration origin and destination, it is important to note that the movement from rural to urban areas, as part of ‘urbanization’ discussed in the literature, refers more to the movement of people from rural areas of the country to the big cities. On the other hand, the rural to urban movement in this chapter is defined as a movement of people from a village classified as rural to another village categorized as urban, which can be within the district or beyond. The destination urban village may not necessarily be part of a city so that the rural to urban movement is not a rural to city movement. This notion is important to keep in mind, as the definition of rural and urban used in the survey is determined at the village level, based on a combination of factors such as population density, share of nonagriculture in the economy and availability of urban facilities in the village (BPS http://www.bps.go.id). Accordingly, one needs to establish a city as a new category of destination (from the place identifiers used in the survey) to be able to address the urbanization issue.

The IFLS is arguably among the most comprehensive and complicated surveys due to its panel data approach and detailed coverage and content. The IFLS represents about 83% of the Indonesian population, covering 13 major provinces out of the total 27 provinces that Indonesia had at that time (Strauss et al. 2009). Provinces excluded from the IFLS are those in the eastern part of Indonesia, where the population density is still very low so that the cost of conducting a survey per household is very high. After cleaning the data such as dropping some household samples due to missing/incomplete data and nonresponse, this research uses about 35,679 panel household members from IFLS3 and IFLS4.

In relation to the internal migration issue, a lower-level administrative boundary of subdistrict is adopted to define internal migration. Accordingly, the shortest distance of migration is within a district so that any movement covering distances shorter than this such as within a village is not included as internal migration. This approach is different with those using the district or province to define internal migration, and this can better capture the dynamics of internal mobility. Therefore, internal migration in this research covers mobility within districts, within provinces and across provinces during the period of 2000 and 2007. Internal migration is then further classified by urban and rural origin and destination, whether it is done individually or with the whole family and different distances covered. In terms of how migrants move, internal migration can be seen as moving individually (split household) or moving with the whole family (whole household).

Figure 6.2 shows a complete classification of internal migration in Indonesia. As can be seen from the picture, the individual is first grouped into migrant and non-migrant based on the fact of whether they have moved or not, which is identified from their address between the two periods of 2000 and 2007. The migrant group is then further classified into current and return migrants, with the current migrant categorized into two types—‘away’ current migrant and ‘staying’ current migrant. The away current migrant is the current migrant originating from the previous IFLS household that was currently away from the household while staying current migrant is the current migrant coming from the same IFLS household that was currently staying in the household. To capture the dynamics of current migrants, both away and staying current migrant must be considered. Therefore, there would be three types of migrants: away current migrant, staying current migrants and return migrants. Given the complex nature of internal migration and the importance of considering the migration cycle in analysing the effect of migration, the analysis would be conducted for the current and return migrants. This is important, as their characteristics could be very different and the effects of migration on poverty reduction may take time to realize.

Classification of internal migrants in Indonesia. (Source: Authors’ classification based on the coverage of the research and data used from IFLS3 in 2000 and IFLS4 in 2007. [From http://www.rand.org/labor/FLS/IFLS.html])

4 Methodology

A combination of methods is used in this study. First, a cross tabulation and descriptive statistics are used to analyse the mobility of people within districts, within provinces and across provinces, including examining whether they migrate individually or with the whole family. The same methods are also used for analysing their movements from rural or urban areas to destinations in rural or urban areas. The reasons for migration of away current migrants could be work, family related, schooling and others. Understanding these patterns and dynamics of internal migration is an important aspect of understanding the internal migration issue. These patterns and dynamics are then linked to poverty conditions before and after migration by comparing with the condition of the non-migrant group as a benchmark. To examine the distribution of expenditures of migrants and non-migrants and where the migrants coming from, a quintile analysis of per capita expenditure is performed.

Second, an econometrics probit model based on the panel data is employed to further determine factors that drive migration. This is also to observe the different characteristics of migrants based on their urban and rural origin. As the intention is to see the effect of migrants’ characteristics, the analysis focuses on the main factors associated with the poverty condition, such as per capita expenditure, agriculture as the main income source and lack of housing ownership. The model also takes into account urban and rural areas as well as demographic factors, such as the number of family members in the household, the number of primary school children (aged 6 to 11 years), the number of middle school children (aged 12 to 14 years) and the number of persons in productive age (between 15 and 64 years), household head age, male household head and marital status of the household head. The inclusion of the variables is to improve the ability of the model to predict, as there can be some other variables that cannot be captured by the main variables but can be captured in the model with the additional variables. The study also looks at the role of education in influencing migration, which is why the variable of average length of study of the household members is also included.

To anticipate the selection effect that migrants might be poorer than non-migrants, an additional variable of squared per capita expenditures is included in the model to account for a possible non-linear relationship.

5 Key Findings and Analysis

The key findings and analysis of cross tabulations and descriptive statistics are presented as patterns and dynamics of internal migration, which cover an analysis of the population that migrated by distance and among urban-rural, the type of migration and whether it was individual/split or with the whole family. The analysis also examines the reasons for ‘away’ current migration, poverty status and gender. The econometrics method is presented in the analysis of what sort of people migrated.

5.1 Patterns and Dynamics of Internal Migration

Results in Table 6.2 show that 28% of the population has migrated over the 7-year period. Among the migrants, 17% are away current migrants and 56% are staying current migrants while the remaining 28% are return migrants. This implies that internal migration has been going on for a long time, and it is not a new phenomenon. Given that the IFLS has covered about 83% of the Indonesian population covering 13 major provinces out of the total of 27 provinces, then the higher share of staying current migrants compared to the away current migrants shows that more people stay in the same household rather than move to a new household outside the IFLS sample. This reflects the strong family connection among internal migrants, which can still be directly maintained in internal migration. This fact provides an additional explanation for why internal migration is theoretically more significant than international migration in terms of the number of people involved.Footnote 5

A majority of the migrants—60%—move as individual migrants, so the share of migrants who move with the whole family is about 40%. This is expected since individual migration is much more common, as it is relatively more flexible and relatively less ‘costly’ than whole family migration . The large share of migrants with the whole family migration (40%) undermines the dynamics of the Indonesian population as part of the significant structural transformation in the economy. This must also be related to flexibility and lack of restrictions for internal mobility in the country. Moreover, this finding also shows an encouraging phenomenon of a higher level of integration or unity within the country given that the country is home to a significant number of ethnic groups with different cultures and languages.

On the distance covered (Table 6.3), a majority of migrants move within provinces (58%), followed by moving across provinces (25%) and within districts (16%). In the context of existing migration literature that the longer the distance, the less the number of migrants (for instance, the gravity model), this finding seems to suggest that a district provides relatively more homogeneous characteristics that can be associated with similar opportunities. Therefore, migrants see moving within districts as the least desirable option, even though at the same time, it might be the most convenient way. In other words, moving within a district can be seen as providing the least favourable opportunity that the migrant is commonly looking for. Beyond the district, the migration distance is still an important factor in internal migration and consistent with the theory’s prediction of the longer the distance, the less the number of migrations.

Comparing current migrants and return migrants, there seems not much changing in the migrant destinations. Migration within provinces remains the most popular destination, but migration across or to other provinces has become less. This is interesting since one may expect that migration to other provinces should tend to increase given the increasing number of provinces. On the other hand, this finding suggests that the average distance of internal migration in Indonesia tends to decrease, which is in line with the increasing number of centres of agglomerations—that is, areas producing more job opportunities.

Among current migrants and return migrants, the share of migrants who move with the whole family has been increasing. Their share has increased by only less than 4% among return migrants, while it is about 18% among away current migrants and almost 80% among hosted current migrants. In other words, migration with the whole family has been increasing over time.

About 52% of migrants are from urban areas and the remaining 48% are from rural areas (Fig. 6.3a). Most migration movements are from the same type of areas, such as from urban to urban and rural to rural. Movements from rural to rural contribute to 40% of the total migration, while urban to urban migration is about 37%. Migration from urban to rural is about 15%, while rural to urban is only about 8%. Therefore, there are more numbers of migration from urban than from rural areas based on the classification used in this research.

5.2 Reasons for ‘Away’ Current Migration

Looking at the main reasons for ‘away’ current migration, the most dominant one is related to family, which contributes to about 39% of the total migration (Fig. 6.3b). This is followed by work (26%) and schooling (only 7%). This pattern is common for both individual migrants and migrants who move with the whole family, though it is more prominent in the case of the former.

In relation to distance, migration due to family reasons is highest among migrants who move within districts, followed by those who move across and within provinces (see Appendix Table 6.10) while the previous result indicates that most migrants move within provinces, followed by across provinces and then within districts. Therefore, there seems to be no clear and systematic pattern between family reasons and migration distance, though one may expect that family connections in the original place will make the number of migrations to farther destinations less—that is, strengthening the gravity model of the distance being negatively correlated to the number of migrations.

In terms of schooling, there is a catchment area system in primary and secondary schools that influences the decision of people or households to move to or stay in the catchment area depending on the location of their favourite (high-quality) school. For the tertiary education level, however, universities are not widely accessible and are commonly located in cities and/or provincial capitals. The number of specific faculties or courses in universities is even more limited. These factors may force people to move to get access to a university. Most migrants moving for schooling reasons move within districts, comprising 11 of the total migrants, followed by within provinces and across provinces, with 7% and 6% shares, respectively.

Looking at the linkages between the reason for migration and the destination areas, one finds that the work reason is more dominant among those moving from rural to urban areas, followed by within rural, urban to urban and urban to rural (see Appendix Table 6.11). For nonagricultural work, it is expected that urban areas will provide more job opportunities than rural areas, so migration to urban areas tends to be more dominant.

On the other hand, among migrants moving for family reasons, the highest share is movement within urban areas, followed by movement within rural, urban to rural and rural to urban. For schooling reasons, the highest share is of migration from rural to urban areas, followed by within rural, within urban and from urban to rural. The results indicate that the reasons for migration do influence the destination of migration (see Appendix Table 6.12, Table 6.13, Table 6.14, and Table 6.15).

5.3 Poverty Status Before and After Migration

On the poverty status, it is important to note that both migrant and non-migrant groups experience poverty reductions. Among the non-migrants, the poverty rates declined from 18% in 2000 to 4.7% in 2007, showing a reduction of 13.3 percentage points (Table 6.4). For the total migrants, the poverty rate in 2000 was 16%, declining to 3.3% in 2007—a reduction of 12.6 percentage points.

If the migrant households are classified further into current migrants and return migrants, the poverty reduction in the two groups is very different. The poverty rate among return migrants in 2000 was 17.4%, and it declined to 0.3% in 2007, showing a remarkable poverty reduction of more than 17 percentage points. For the away current migrants, the poverty rate in 2000 was 12.4%, and it declined to 7.4% in 2007—a reduction of only 5 percentage points. The poverty rate of staying current migrants was 16.2% in 2000 and it declined to 3.5% in 2007, showing a reduction of 12.7 percentage points. Therefore, the poverty reduction of staying current migrants is almost 8 percentage points higher than that of away current migrants. The findings show that the poverty reduction effect of internal migration takes time to realize, and there is also a worsening period when the migration is still in process. The success of returning migrants in reducing poverty is really remarkable to the extent that the poverty incidence among them is nearly eradicated. Moreover, the higher rate of poverty reduction among the staying current migrants compared to the away current migrants suggests that being with the family is helpful, as other family members may contribute to reducing the poverty incidence.

Looking further into a specific household group that was poor in 2000 and then became non-poor in 2007, one finds that the share of non-migrants is 16.1% while the share of away current migrants, staying current migrants and return migrants is 11.5%, 14.6% and 17.3%, respectively (see Appendices 3, 4, 5 and 6). Therefore, a complete cycle of internal migration helps further reduce poverty by about at least 3 percentage points.

On the other hand, there is also a household group that was not poor in 2000 but became poor in 2007. The share of non-migrants in this group is about 2.8% while the share of the away current migrants, staying current migrants and return migrants is 6.6%, 1.9% and less than 0.5%, respectively. This highlights that migrants struggle and some of them become poor in the process, even though by the end of the migration process, most of them manage to succeed.

Linking poverty reduction effects with the patterns and dynamics of migration, some interesting findings emerged. First, in terms of how people migrate, the highest share is movement within districts, followed by within provinces and across provinces (Table 6.5). This pattern is more common among individual migrants than those who move with the whole family. Individual migrants are much more successful in helping themselves escape poverty than migrants with the whole family. The poverty reduction among individual migrants reaches 14 percentage points, while that among whole family migrants is only 10 percentage points. Among the whole family migrants, poverty reduction among those moving within districts and across provinces is the same at about 11.3 percentage points migrant. The smallest poverty reduction is among those moving within provinces.

Among current migrants, the overall poverty reduction of individual migrants and those migrating with the whole family is about the same at 11.2 and 10.6 percentage points, respectively. Individual migration within districts experiences the least poverty reduction—only 6.9 percentage points.

Among return migrants, poverty reduction of individual migrants is almost 18 percentage points while the rate for whole family migration is less than 5 percentage points. There is no impact among return migrants moving with the whole family within districts, as there is no movement of poor migrants within the group. Overall, migrants moving within districts show the highest poverty reduction, while migrants moving across provinces experience a reduction of only 2 percentage points.

Second, Table 6.6 presents poverty reduction in relation to areas of movement. Overall, the highest poverty reduction is among migrants moving within urban areas, which is 14.9 percentage points, followed by those moving from urban to rural at 12.2, within rural at 11.7 and the least from rural to urban at 6.4 percentage points. These reductions are also observed among return migrants, but they are much higher—23.1 percentage points among those moving within urban areas, 15.7 from urban to rural, 15.4 within rural and 12.5 from rural to urban.

The poverty reduction situation among current migrants is very different. The highest is still among those moving within urban areas (13.2 percentage points), followed by movement within rural (10.4) and from urban to rural (8.5) and the lowest one is from rural to urban (2.9). The poverty reduction among return migrants is always higher compared to current migrants for all types of movements and the highest difference is among those moving within urban areas, which is almost 10 percentage points. The lowest difference is among those moving within rural (5 percentage points only) while the difference for those moving from rural to urban and from urban to rural is 9.6 and 7.2 percentage points, respectively.

Looking at the link between the way migrants move and the area of movement, one finds that individual migrants contribute significantly to poverty reduction for all types of migrants (i.e. current and return migrants), but the results are very different in the case of whole family migration . The poverty reduction of individual return migrants moving within urban areas is very high at 23.4 percentage points, followed by those moving within rural and from urban to rural, which is the same at 16.4 percentage points, and those moving from rural to urban at 13.9 percentage points. However, there are no effects on migrants who move with the whole family from rural to urban areas and within rural areas, as there are no poor migrants who move within these groups. The results for migrants moving with the whole family in this return migration should be interpreted more cautiously due to the small size of the sample. On the other hand, individual migrants and those who move with the whole family have a similar effect on poverty reduction at about 11 percentage points. The movement from rural to urban contributes the least, followed by migration from urban to rural, within rural and from rural to urban.

Finally, with regard to the migration reasons of the away current migrants and their relation to poverty reduction, those who move for schooling reasons show the highest poverty reduction, which is 8.9 percentage points, followed by those who move for family reasons at 4.6. The least poverty reduction is among those who move for work-related reasons, which is 1.7 percentage points only, while it is 7.4 points among those who move for ‘other’ reasons (Appendix Table 6.16).

5.4 Considering Gender

To consider the gender dimension in the analysis, cross tabulations of migrants by type with gender are made as well as with regard to the poverty impact. The results show that there are more male migrants than female migrants, but the difference is very small. This applies for different types of migrants and the differences are less than 1% (Table 6.7). This shows that women have been part of the internal migration in all cases.Footnote 6

On the poverty impact, it seems that gender is not a determining factor in influencing the internal migration results, and the effects across different types of migrants show no systematic pattern. The poverty reduction impact among female non-migrants is only slightly higher than the male—13.4 compared to 13.2 percentage points, but the impact among migrants is different, with males performing better, though the difference is again very small—12.7 for male migrants and 12.4 for female migrants (Table 6.8). The only noticeable difference is among the away current migrants, in which case the poverty reduction declined by 6.5 percentage points for males but was only 3.1 percentage points for females.

Looking at the initial condition in 2000, poor female migrants, both away and staying current migrants, are fewer than male migrants, while the number is higher among return migrants (see Appendix Table 6.17).

Who Migrate?

The quintile analysis of the per capita expenditures of migrants and non-migrants shows a very different result. Figure 6.4 presents the frequency distributions of migrants, which are concentrated in the upper levels of the quintiles, while it is the opposite in the case of non-migrants. More than 35% of away current migrants, about 25% of staying current migrants and 23% of return migrants come from the top quintile group, while it is only 19% in the case of non-migrants. This indicates that migrants are coming from richer groups.

Table 6.9 shows regression results on the factors influencing people to migrate. As can be seen from the results, the monthly per capita expenditure and housing ownership status have positive signs showing that people with stable incomes and the rich tend to migrate. The negative sign of the squared per capita expenditure coefficient strengthens the finding. This shows that migrants are less poor than non-migrants. Households with agriculture as the main income source show a negative sign, indicating that agriculture household do not tend to migrate. This may also indicate that the agriculture households need their members to do farm work, making them less likely to migrate. This finding is also in line with the result that migrant households are more likely to be from urban areas than from rural because agriculture jobs in urban areas are less than in rural.

Analysing the demographic factors, people in households with more family members, more members of productive age and a male household head tend to migrate. On the other hand, households with more older members and married household heads have a negative sign, showing that they are less likely to migrate. Looking at the role of education, households with a larger number of middle school children and higher education members show positive signs, reflecting that they are more likely to migrate. Households with more primary school children show a negative effect and are less likely to migrate. This may be related to the widespread availability of facilities for compulsory primary and secondary education in the catchment areas where they live.

The economic factors of the model results for urban and rural areas show similar results. All signs on household per capita expenditures and housing ownership status are the same. The squared per capita expenditure among those moving have the same signs except for those moving from rural to urban, which shows that migrants from rural to urban areas tend to be poorer than non-migrants. Other types of migrants who moved from urban to rural areas tend to be richer. An agriculture income source has the same negative results except among those moving from urban to rural, which is positive. This means that households with agriculture as the main income source are more likely to migrate from urban to rural to get back to farming in rural areas.

The demographic factors of all migrants based on areas of movement show a common pattern as in the overall model. Households with higher numbers of elderly members and married household heads are less likely to migrate, and households with higher numbers of male household heads are more likely to migrate. People from households with a larger household size are less likely to migrate except in the case of movement within urban areas. Therefore, the relationship between family size and migration is also affected by the origin and destination of migration. Household members of a more productive age are more likely to migrate except in the case of movement within rural areas. On the other hand, people from households with a larger number of middle school children are more likely to migrate in all the areas of movement, while those from households with larger numbers of primary school children are more likely to migrate in the case of movement within rural and from urban to rural areas. Finally, higher education household members are more likely to migrate in the movement from rural to urban and within rural areas, but it is opposite in the movement from urban to rural and within urban.

6 Conclusions and Policy Implications

The extent and effects of internal migration have increased and are becoming more significant. On the other hand, the dynamics and patterns of internal migration have become complex, especially with regard to how the migration is conducted, the main reasons, the distance covered and the origin, destination and characteristics of the migrants. There is a need for a rigorous analysis to address these issues.

More internal migration takes place at the individual level, with a majority of the individual migrants moving within provinces. More migrants are from urban areas, and most migrants move within the same area, such as urban to urban and rural to rural, while rural to urban migration is actually the least common. This is very different from the perception of internal migration from the literature, which is dominated by rural to urban migration (i.e. urbanization). This rural to urban migration primarily refers to movement from rural areas to cities.

The poverty effects of internal migration seem to be influenced by the migration type:

-

(i)

First, the poverty condition of both migrants and non-migrants has improved during the period studied.

-

(ii)

Second, poverty reduction among return migrants is higher than among current migrants. This highlights that the poverty reduction effect of internal migration takes time to materialize or that the poverty reduction effect on current migrants is not fully realized. In other words, migrants must struggle to escape poverty at the beginning, as the full impact on poverty reduction can only be seen when the cycle of migration is completed.

-

(iii)

Third, the strongest poverty reduction effect is among those moving within districts, showing that the shorter the distance, the stronger the poverty reduction effect. This seems consistent with the theoretical prediction that the longer the distance, the more costly and stronger the barriers to migration. The results also show that the shortest distance of migration is more pro-poor, as the poverty incidence of people moving within districts is the highest compared to those moving within provinces and across provinces.

-

(iv)

Fourth, poverty reduction in the case of individual migration performs better than in the case of whole family migration , which is a matter of concern and requires more attention. Whole family migration seems to be facing more barriers when it comes to poverty reduction.

-

(v)

Finally, those moving from urban to urban areas experience the most pro-poor effects than other types of movement, and those moving from rural to urban areas face more challenges.

The gender effect is less obvious and shows no clear pattern. Moreover, migrants tend to come from a rich background, with more productive age and higher education members. They are less likely to be from households that are dependent on agriculture and households with more primary school children, which are linked to migration reasons and household circumstances, such as the availability of jobs, higher-level schooling and the catchment area system implemented at the primary school level.

The overall findings indicate the complexity of the internal migration issue, especially in relation to its poverty reduction effects. This calls for further examination so as to distil more detailed policy implications. The more obvious conclusion from this research is that the migration cycle, individual or family migration, distance, origin and destination, migration reasons and characteristics of migrants are all significant in influencing the migration results. Therefore, these factors should be taken into account in addressing the various internal migration issues, including transmigration and introduction of barriers to migration to big cities.Footnote 7

It is clear from the different impacts for the different migrant groups that there will be no one strategy that can address all the issues, as each case requires a specific intervention. Whole family migration requires greater attention, and there is a need for better facilitation to complete the migration cycle, which will contribute positively to poverty reduction. Moreover, considering the migration dynamics, reducing the overall migration costs and improving the human capacity of the migrants will further augment the positive impact of internal migration.

Notes

- 1.

In the colonial period, the 1930 Indonesian census was the last census that had information on the place of birth and place of residence, and it was more reliable compared to the previous one in 1920. Post-independence, the Indonesian government conducted the first comprehensive census in 1961, followed by similar censuses every 10 years—1970, 1980, 1990, 2000 and 2010. In between the population census years, there have also been inter-census population surveys.

- 2.

Many have argued that the spatial aspect is not limited to the place of residence since migration can also be viewed as a result of spatial differences in many aspects that make people move from their original place to a new destination (Greenwood 2005).

- 3.

BPS-Statistics Indonesia has used the concept of the basic needs approach to estimate poverty incidence. The concept measures poverty based on consumption expenditure on basic goods and services as the poverty line.

- 4.

Consumption outlays based on the national poverty line Rp 302,735 (US$25) per month per person (Aji 2015).

- 5.

This is obviously different from international migration in which the migrants must stay away from their families.

- 6.

This finding is very different compared with international migration in which women international migrants are dominant.

- 7.

The capital city of Jakarta once introduced ‘a close city policy’ to prevent migrants with no jobs and other guarantees to enter the city. Many other big cities try to copy the policy but end up with no clear implementation or results.

References

Aji, P. (2015). Summary of Indonesia’s poverty analysis, ADB Papers on Indonesia, No. 4 https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/177017/ino-paper-04-2015.pdf. Accessed on 12 Dec 2017.

Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS). http://www.bps.go.id, Indonesia.

Bell, M., & Muhidin, S. (2009). Cross-national comparisons of internal migration, Human Development Research Paper 2009/30, UNDP.

Deb, P., & Seck, P. (2009). Internal migration, selection bias and human development: Evidence from Indonesia and Mexico. Online at http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/19214/. MPRA Paper No. 19214, posted 13. December 2009 06:54 UTC.

Deshingkar, P. (2006). Internal migration, poverty and development in Asia. Promoting growth, ending poverty ASIA2015. Institute Development Studies and Overseas Development Institute.

Greenwood, M. J. (2005). Modelling migration. Encyclopedia of social measurement, Volume 2, Elsevier Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Harris, J., & Speare, A. (1986, January). Education, earnings, and migration in Indonesia. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 34(2), 223–244 Published by: The University of Chicago Press.

Harttgen, K., & Klasen, S. A human development index by internal migration status. Human Development Research Paper 2009 / 54, UNDP.

IFLS 3. (2000). Available: https://www.rand.org/labor/FLS/IFLS.html

IFLS 4. (2008). Available: https://www.rand.org/labor/FLS/IFLS.html

The House of Commons International Development Committee. (2004). Migration and development: How to make migration work for poverty reduction, Sixth Report of Session 2003–04 Volume I.

Hugo, G. J. (1982, March). Circular Migration in Indonesia. Population development review, 8(1), 59–83 Published by: Population Council.

Hugo, G. J. (2004). Forced migration in Indonesia: Historical perspectives. In Revised paper presented to international conference on toward new perspectives on forced migration In Southeast Asia, organised by Research Centre for Society and Culture (PMB) at the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) and Refugee Studies Centre (RSC) at the University of Oxford, Jakarta, 25–26 November 2004.

Lu, Y. (2008). Test of the “healthy migrant hypothesis”: A longitudinal analysis of health selectivity of internal migration in Indonesia. Social Science and Medicine, 67, 1331–1339.

Lottum, J. V., & Marks, D. (2010). The determinants of internal migration in a developing country: Quantitative evidence for Indonesia, 1930–2000. JEL codes: J61; J68; N15; O15.

McNicoll, G. (1968). Internal migration in Indonesia: Descriptive notes. Published by: Southeast Asia Program Publications at Cornell University.

Perlman, J. E. (1976). The myth of marginality: Urban poverty and politics in Rio de Janeiro (pp. xxi–341). Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press.

Rondinelli, D. A. (1985, June). Population distribution and economic development in Africa: The need for urbanization policies. Population Research and Policy Review, 4(2), 173–196.

Strauss, J., Witoelar, F., Sikoki, B., & Wattie, A. M. (2009). User’s Guide for the Indonesia Family Life Survey, Wave 4. Working Paper Volume 2, 2009. RAND Labour and Population.

Tacoli, C. (2012). Urbanization, gender and urban poverty: Paid work and unpaid carework in the city. Urbanization and emerging population issues, Working Paper 7. United Nations Population Fund.

World Population Year. (1974). The population of indonesia. Lembaga Demography Universitas Indonesia. CICRED Series.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendices

Rights and permissions

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent.

ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.

By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term "country" in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area.

Open Access This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 IGO license (CC BY-NC 3.0 IGO)http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/igo/. By using the content of this publication, you agree to be bound by the terms of this license. For attribution and permissions, please read the provisions and terms of use at https://www.adb.org/terms-use#openaccess.

This CC license does not apply to non-ADB copyright materials in this publication. If the material is attributed to another source, please contact the copyright owner or publisher of that source for permission to reproduce it. ADB cannot be held liable for any claims that arise as a result of your use of the material. Please contact pubsmarketing@adb.org if you have questions or comments with respect to content, or if you wish to obtain copyright permission for your intended use that does not fall within these terms, or for permission to use the ADB logo.

Copyright information

© 2019 Asian Development Bank

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Sugiyarto, E., Deshingkar, P., McKay, A. (2019). Internal Migration and Poverty: A Lesson Based on Panel Data Analysis from Indonesia. In: Jayanthakumaran, K., Verma, R., Wan, G., Wilson, E. (eds) Internal Migration, Urbanization and Poverty in Asia: Dynamics and Interrelationships . Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1537-4_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1537-4_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-1536-7

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-1537-4

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)