Abstract

The impact of economic reforms of 1991 was quite significant on India’s economic growth. For example, the average growth rate of gross domestic product was significantly higher at about 6.96% for the years 1992–1993 to 2011–2012, at 2004–2005 prices. However, the main problem encountered by India economy is the unequal distribution of the benefits of higher economic growth, as evidenced by the lower increases in the standard of living of low-income groups, particularly for the lower castes. In recognition of this fact, the Twelfth Five-Year Plan (2012–2017) has fixed its main objective as ‘faster, sustainable and more inclusive growth’ so that benefits of higher economic growth are distributed more evenly to those sections of people who were left out.

The views expressed in the study do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of India.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

JEL Classification

1 Introduction

The impact of economic reforms of 1991 was quite significant on India’s economic growth. For example, the average growth rate of gross domestic product was significantly higher at about 6.96% for the years 1992–1993 to 2011–2012, at 2004–2005 prices. However, the main problem encountered by the Indian economy is the unequal distribution of the benefits of higher economic growth, as evidenced by the lower increases in the standard of living of low-income groups, particularly for the lower castes. In recognition of this fact, the Twelfth Five-Year Plan (2012–2017) has fixed its main objective as ‘faster, sustainable and more inclusive growth’ so that benefits of higher economic growth are distributed more evenly to those sections of people who were left out.

Currently, India like most other developing countries is going through a transformation from rural- to urban-based economy. This is evident in the high increase in the absolute number of urban population compared to rural population as of 2011; the percentage of urban population increased from 17.97% in 1961 to 31.16% in 2011. In fact, Indian cities are growing very fast. For instance, Delhi (25 million populations) became the second most populous city after Tokyo (38 million population) in 2014 (United Nations 2014) . According to the projections by McKinsey Global Institute (2010), Indian cities will accommodate about 590 million population by 2030. The number of million plus cities has increased sharply in India, from 35 in 2001 to 53 in 2011. The number and share of urban population of Class I cities (population with 1 lakh and more) also has increased from 107 (or 51.88% of total urban population) in 1961 to 468 (or 70.24% of total urban population) in 2011. This suggests that in the coming decades, more Indians will be living in Class I cities.

However, India is still relatively less urbanized compared to other countries, with an urbanization rate of 32% in 2014, which is much lower than the global level of 54%. This could be because of the lower rural-urban migration in India. The existing caste system; the diversity of language and culture, traditional values and joint family system; the lack of education; and the predominance of agriculture, semi-feudal land relation and traditional values are found to be the main reasons behind this lower rural-urban migration (Davis 1951). Census data in 2001 (as 2011 Census is yet to be published) shows that India’s interstate migration was about 4% (41 million) compared to 26% (268 million) intra-state migration (Bhagat 2010). Table 11.1 shows that about 35% of India’s urban population consist of migrants, according to the latest National Sample Survey (NSS) in 2007–2008. Table 11.1 also shows that the rate of migration declined from 1981–1983 to 1991–1993 of the Census and NSS years. Most importantly, after the Census and NSS year of 1991–1993, the rate of migration to urban areas has increased. The latest NSS data, i.e. 2007–2008, also confirms the increase in the rate of migration. Most importantly, NSS data of 2007–2008 shows that female migration rate to urban areas is much higher than male migration rate.

As India is going through a transformation from agriculture to industry- and service-based economy, it has increased the hope of the rural people of getting higher job opportunities, which in turn has resulted in higher rural-to-urban migration. On the other hand, slow agricultural growth and inadequate development of the rural non-farm sector have forced the rural poor and unemployed people to migrate to urban areas as urban areas provide higher wage rate through realization of higher productivity. Rural-to-urban migration in million plus cities was estimated at 20 million (56%) migrants in 2001. The proportion of male and female was almost equal at more than 55%.

It is also important to note that rural-to-urban migration for male (or female) was 34.2% (or 13.5%) as per the Census 2001. On the other hand, as per NSS data, in 2007–2008, rural-to-urban migration rate for male (or female) was 39% (or 14.8%). Table 11.2 lists the top 10 urban agglomerations which received the highest rural-to-urban migration in 2001. Table 11.2 confirms that the bigger (as per the population size) cities have received higher (more than 50%) migrants from rural areas. The economy of all the cities listed in Table 11.2 mainly depends on industry or service sector. This indicates that industry (such as textiles, diamond polishing, coal) and service sectors are the main drivers of rural-to-urban migration.

The growing urban economy is making a significant contribution to India’s GDP. The share of urban net domestic product (NDP) to national NDP increased from 37.65% in 1970–1971 to 52.02% in 2004–2005. Urban NDP growth rate (compound annual growth rate) was about 8.1% for the years 1993–1994 to 2004–2005, at 1999–2000 prices. The urban share in the total gross domestic product was about 63%, and according to Mid-Term Appraisal of the Eleventh Five-Year Plan projections, it will increase to 75% by 2030.

It is worth noting that despite this visible increase, urban India is also experiencing rise in inequality and decrease in poverty. For instance, consumption inequality (Gini coefficient) increased from 0.36 to 0.38 during the period of 2005–2012. In contrast, urban headcount poverty ratio, measured by Tendulkar’s recommended poverty line, declined from 25.76% to 13.69% during the period of 2005–2012. This indicates that though urban India is experiencing higher economic growth, it is not being distributed equally among the urban dwellers.

Several poverty alleviation programmes have also been made operational under different Five-Year Plans. For example, in 1995, the Prime Minister’s ‘Integrated Urban Poverty Eradication Programme’ incorporates the small towns’ urban poverty alleviation. The Swarna Jayanti Shahari Rozgar Yojana is another programme introduced to create self-employment for urban unemployed persons. The Twelfth Five-Year Plan (2012–2017) tries to address the problems (e.g. access to basic amenities such as education, sanitation, health care, water supply, social security and affordable housing) faced by urban dwellers working in urban informal sectors. Rajiv Awas Yojana (2013–2022) has been implemented to provide affordable housing to urban slum dwellers.

Several policies have been introduced by the Government of India in recent years to promote urbanization in India. For example, 100 Smart Cities Mission deals with promotion of mixed land use in area-based developments, expansion housing opportunities for all, creation of walkable localities, preservation and development of open spaces and promotion of variety of transport options. Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) focuses on providing basic services, such as water supply, sewerage and urban transport. It seeks to ensure that every household has access to piped water with assured supply and also sewerage connection. The Swachh Bharat Abhiyan is a massive movement that seeks to create a cleaner India. The programme includes building individual household toilets, community and public toilets and municipal solid waste management in the towns. The Digital India has a vision to transform India into a digitally empowered society and knowledge economy. It is hoped that all these major programmes and policies will reshape urban India for making higher contribution to economic growth along with reduction of poverty and inequality.

Government intervention has to be assessed so that right policies are taken up with scope for time-to-time revision. To plan, supervise and implement poverty reduction policies, it is very important to know the poverty figures not only for a particular time but also for different time periods. Therefore, evaluating of pro-poorness of growth is essential to ensure higher and sustainable development . Ultimately, we have to ensure proper distribution of the accruals from higher economic growth by formulating appropriate policies; otherwise it will lead to further increase in inequality and several socio-economic problems among the urban dwellers.

With this backdrop, the main objectives of this chapter are as follows: first to measure the poverty and inequality situation in urban India and second to empirically estimate the pro-poorness of distributive changes of urban economic growth; and finally, the chapter seeks to identify appropriate policies for efficient distribution of urban economic growth. The study covers the periods from 2004–2005 to 2011–2012, and the available unit-level data for three rounds—61st round for 2004–2005, 66th round for 2009–2010 and 68th round for 2011–2012—of urban monthly per capita expenditure (MPCE) have been used for analysis in conjunction with data from the National Sample Survey (NSS) conducted by the Department of Statistics of the Indian government (NSSO 2006, 2011, 2013) for analysis.

The framework proposed by Duclos (2009) based on the methodology of Araar et al. (2007, 2009) and Araar (2012) has been used to measure the pro-poorness of urban economic growth. Duclos (2009) formulated two approaches, i.e. relative and absolute, to measure poverty. Relative approach measures the pro-poor growth rate by considering some standard (usually the average growth rate of the median or the mean). Absolute approach measures the pro-poorness by considering absolute income of the poor. These frameworks are based on proper theoretical structure and analyse pro-poor growth in a dynamic manner by employing statistical rationale. The results are very important to formulate appropriate policies for proper distribution of higher urban economic growth.

The rest of the chapter is structured as follows: The following section provides a brief review of literature, the third section describes the poverty and inequality situation in urban India, the fourth section measures pro-poor growth by explaining the theoretical model and empirical results of pro-poor growth assessment and, finally, the last section presents the summary of findings, conclusions and discussions.

2 Review of the Literature

There are very limited numbers of studies that measure the pro-poorness of economic growth in India. Datt and Ravallion (2009) measured and compared the pro-poor growth in terms of reduction in poverty and elasticity of poverty with respect to economic growth by considering pre- and post-reform periods in India separately.Footnote 1 Using consumption expenditure data for the periods of 1958 to 2006, the authors found evidence for long-run decline of poverty as measured by poverty headcount ratio, poverty gap ratio and squared poverty gap ratio . But a higher proportionate rate of action against poverty after 1991 is also evidenced by them. This shows that post-reform India became less pro-poor. They also found evidence of the trickle-down effect of higher economic growth on reduction of rural poverty in the pre-1991 data.

Using 2009–2010 NSS data, Liu and Barrett (2013) investigated the patterns of job seeking, rationing and participation under Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) and found that the scheme is not pro-poor as it exhibits a middle-class bias. Dev (2002) examined the degree of pro-poor growth by measuring several quantitative and qualitative aspects of employment, such as employment elasticities of growth, labour productivity, wage rates and job security for the period of 1980 to 2000. The study found a declining trend in the quality of employment in different sectors (e.g. agriculture sector) . The growth rate of employment was positive, but it declined for the period of 1994–2000.

In the context of pro-poorness of the institutional interventions, a cross-sectional study of women beneficiaries under the Muthulakshmi Reddy Maternity Benefit Scheme in five districts of Tamil Nadu by Balasubramanian and Ravindran (2012) showed that scheduled caste landless women have received smaller benefits. Most importantly, Ravallion (2000) suggested a number of conditions which determine the poor’s share in economic growth in India. He recommended that higher and stable agricultural growth is essential for poverty reduction in the long run. Therefore, human and physical resource development in rural areas is essential. Ravallion and Datt’s (1999) study found that initial conditions and sectoral composition of economic growth determine the degree of economic growth and reduction in poverty in India. The above review of literature clearly shows that thrust of pro-poor growth in India is very limited. Therefore, this paper tries to fill this gap by using appropriate statistical techniques to measure pro-poor growth in India.

3 The Poverty and Inequality Situation in Urban India

This section seeks to present the poverty and inequality situation by considering different aspects of urban India by using latest unit-/individual-level data on consumption expenditure provided by NSS. The extent of inequality is measured by Gini coefficient. The poverty headcount ratio (PHR), the poverty gap ratio (PGR) and the squared poverty gap ratio (SPGR) are used to measure poverty. MPCE used in this study is based on Mixed Reference Period (MRP) and the Modified Mixed Reference Period (MMRP), and Gini coefficient is used to measure the extent of inequality in urban India. Inequality and poverty estimations are based on the Mixed Reference Period (MRP), and the Modified Mixed Reference Period (MMRP) is considered over the Uniform Recall Period (URP).Footnote 2

Following the suggestion of the Expert Group (Tendulkar Committee, GOI 2009), MRP-based poverty and inequality estimation is considered while using consumption expenditure data for the 61st, 66th and 68th NSS rounds. The consumption expenditure of a poor household on low-frequency items is better captured by MRP-based estimates compared to URP-based estimates. Following the recommendation of the Expert Group (Rangarajan Committee, (GOI 2014)), MMRP-based poverty and inequality estimation is considered while using consumption expenditure data for the 66th and 68th rounds, as MMRP-based estimates are expected to yield estimates that are closer to their ‘true value’ (Deaton and Kozel 2005).

Table 11.3 presents the poverty and inequality situation by considering different attributes of urban India in different periods of time, using the MRP-based consumption expenditure data based on the Tendulkar Committee’s recommended poverty line.Footnote 3 Urban PHR has declined from 25.8% in 2004–2005 to 13.7% in 2011–2012. This is because of the higher economic growth rate in urban India in recent decades, which led to a reduction in the poverty level. In this context, Tripathi (2013a) estimated that India’s large agglomerations have a robust and positive effect on the city output growth rate as large agglomerations provide higher productivity, wages and capital per worker due to higher economies of agglomeration, which ultimately increases economic growth and reduces the city poverty rate significantly.

The analysis involving the calculated values of the three poverty indices and for three different periods shows that poverty ratios are lower for groups of urban dwellers such as those who have an education level ‘postgraduate and above’, ‘graduate’, ‘diploma’, ‘higher secondary’, ‘secondary’ and ‘regular wage earner’. In contrast, the poverty ratios are higher for the urban dwellers in categories like ‘casual worker’, ‘not literate’, ‘scheduled castes’, ‘scheduled tribes’, ‘other religion group’ and ‘literate without formal schooling’. The extent of inequality has risen from 36.4 in 2004–2005 to 37.7 in 2011–2012. Most importantly, the inequality level is higher for groups like ‘other household type’, ‘other religion group’, ‘adult’, those with education level ‘postgraduate and above’ and ‘male’. The extent of inequality is lower for ‘not literate’, ‘middle-class’ educated people, ‘scheduled caste’, ‘casual labour’ and those who have passed ‘primary’ level education.

Table 11.4 presents the calculated figures of percentage decline of poverty ratios and percentage increase in inequality at different time points during the years 2004–2005 to 2009–2010. As can be seen from the table, PHR declined by about 47% in the periods 2004–2005 to 2011–2012. In contrast, the extent of inequality increased by about 4% during the same period. Categories which experienced a higher decline in the poverty ratio are ‘postgraduate and above’, ‘regular wage/salary earning’, ‘other social group’, ‘other household type’ and ‘scheduled tribe’ during this period. On the other hand, groups like those who have passed ‘middle/higher secondary/graduate/diploma’ experienced a lower percentage decline of poverty ratio in the same time span. Most importantly, those who have passed only secondary-level education experienced an increase in the poverty ratio during the years 2004–2005 to 2009–2010. Coming to the years 2009–2010 to 2011–2012, it was groups like ‘scheduled castes’ and ‘child’ that experienced a higher percentage reduction in poverty ratio. In contrast, categories which experienced a lower-level decline of poverty ratio are ‘postgraduate and above’, ‘higher secondary’, ‘scheduled tribes’ and ‘literate without formal education’. Most noticeably, ‘diploma’ holders experienced an increase in poverty ratio in the years from 2009–2010 to 2011–2012. However, in regard to the percentage of poverty decline for the years from 2004–2005 to 2011–2012, it is groups like ‘other religion’ and ‘female’ that have experienced a high level of poverty decline compared to other categories. Increase in the lower level of inequality is found for groups like ‘other religion’, those who have studied ‘postgraduate and above’ and ‘casual labour’ for the years 2004–2005 to 2009–2010. In contrast, groups like ‘scheduled tribes’, those who have passed ‘higher secondary’, ‘diploma’ holder and ‘scheduled castes’ are found to have experienced a higher rise in the level of inequality during the same period of time. Most importantly, there was a perceptible decline in inequality for the group ‘literate without formal schooling’ in the years 2004–2005 to 2009–2010. The categories that have experienced a decline in inequality in the years 2009–2010 to 2011–2012 are ‘scheduled tribes’, those who have passed ‘higher secondary’, ‘other household types’ and ‘diploma’ holders. On the other hand, there is evidence to show those who have passed ‘postgraduate and above’, ‘below-primary-school’ educated people, ‘literate without formal schooling ‘and ‘casual worker’ experienced a rise in inequality. However, during the time periods from 2004–2005 to 2011–2012, groups like ‘scheduled tribes’, ‘self-employed’ and ‘other household type’ did experience a lower increase of inequality. In contrast, those who have passed ‘graduate’-level education experienced a higher level of increase in inequality during the same period.

Table 11.5 presents the poverty and inequality situation in terms of the different attributes of urban India for the years 2009–2010 and 2011–2012; these figures are calculated by using the MMRP-based consumption expenditure data and by applying the Rangarajan Committee’s recommended poverty line. The poverty estimates show that groups like ‘casual labour’, ‘not literate’, ‘scheduled castes’, ‘scheduled tribes’ and ‘below primary educated people’ experienced a higher level of poverty in 2009–2010. On the other hand, those who have education levels ‘postgraduate and above’, ‘graduate’, ‘diploma’ and ‘higher secondary’ experienced a lower level of poverty in the same time period, while the group ‘literate without formal schooling’ suffered a higher level of poverty in 2011–2012. The extent of inequality was high for ‘other household type’, ‘scheduled tribes’, ‘adult’ and ‘female’ in 2009–2010. On the other hand, the extent of inequality was lower for the groups ‘scheduled castes’, ‘literate without formal schooling’, ‘not literate’ and ‘casual labour’ in the same period of time. In addition, groups ‘postgraduate and above’ and ‘other social group’ registered a higher level of inequality in 2011–2012. In contrast, those who have passed ‘primary’, ‘middle’ and ‘secondary’ experienced a lower level of inequality in 2011–2012.

Table 11.5 also shows that groups like ‘regular wage/salary’ earner, ‘other backward classes’ and those who have ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ level education also experienced a higher level of poverty decline in the periods of 2009–2010 to 2011–2012. Most importantly, as per the squared poverty gap ratio (SPGR) estimation, ‘literate without formal schooling’ and ‘other religion group’ are also found to have experienced a higher-level poverty decline during the same time period. In contrast, groups like ‘literate without formal schooling’, ‘scheduled tribes’, ‘diploma holder’ and ‘other household type’ also showed a lower decrease in the percentage of the poverty ratio during the period. Surprisingly, groups that have an education level ‘postgraduate and above’ also showed an increase in the poverty ratio in the periods 2009–2010 to 2011–2012. Similarly, the level of inequality increased for groups such as those who have passed ‘postgraduate and above’, ‘literate without formal schooling’ and ‘diploma holders’ in the periods 2009–2010 to 2011–2012. In contrast, the groups ‘scheduled tribes’, ‘higher secondary level education’ and ‘middle-class level of education’ experienced a fall in inequality. It is important to note that results arrived based on MRP and MMRP do not differ much from each other.

4 Measurement of Pro-Poor Growth

4.1 Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework developed by Duclos (2009) and Araar et al. (2007, 2009) is used to calculate pro-poor growth in this study.Footnote 4 In the case of India, a similar approach was used in Motiram and Naraparaju (2015). However, this chapter focuses mainly on different specific aspects of urban India only.

The framework such as developed by Duclos (2009) is explained as follows:

The vector of non-negative incomes is presented as\( {y}_{\mathbf{1}}=\left({y}_1^1,{y}_2^1,\dots \dots \dots {y}_{n1}^1\right)\in {\Re}_{+}^{n\mathbf{1}} \) at time 1 of size n1, and let \( {y}_{\mathbf{2}}=\left({y}_1^2,{y}_2^2,\dots \dots \dots {y}_{n1}^2\right) \) be an analogue vector of income set time 2 of size n2.

W(y1, y2,g,z) is the pro-poor evaluation function, where z > 0 represents the poverty line. It is characterized as the difference between evaluation functions π(y1, z) and evaluation function π∗ (y2, g, z), each for time 1 and time 2, respectively, which are analogous to poverty indices for each of the two time periods:

The change from y1 to y2 will be considered as pro-poor if W(y1, y2,g,z) ≤ 0.

The social welfare function of W satisfies the different axioms (i.e. focus, population invariance, anonymity, normalization, monotonicity, distribution sensitivity axioms).

4.1.1 Relative Pro-Poor Measurements

FGT indices in (11.2) are obtained using the assumption that Fj(y) is the distribution function of distribution j and Qj(p) is the quantile function for the distribution Fj. Qj(p) is defined as Qj(p) = inf {s ≥ 0| Fj(s) ≥ p} for p ∈ [0, 1]. If we assume that this is continuous distribution with a positive income density, then Q(p) is the inverse of the distribution function:

where Pj(z; α = 0) is the headcount index (and the distribution function) at z and Pj(z; α = 1) is the average poverty gap.

A measure of movement from y1 to y2 will be reflected as pro-poor by all such functions if

Equation (11.3) shows a distributional change. All pro-poor evaluation functions within Ω1(g, z+) find that it is pro-poor and this for any selection of poverty line within [0, z+] and any W complies with the already indicated axioms. Validating (11.3) accommodate examining the range of poverty lines[0, z+]. The headcount ratio in the initial distribution is higher than the headcount ratio in the subsequent distribution when that distribution is normalized by 1 + g. In other words, one can measure first-order relative by using the ratio of quantiles and(1 + g).

Therefore, we need to check whether for all p ∈ [0, F1(z+)]

The use of (11.4) is identical to ‘growth incidence curves’ as suggested by Ravallion and Chen (2003).

The class Ω2(g, z+) is the subset of Ω1(g, z+) where the evaluation function maintains the distribution sensitivity axiom. A movement from y1 to y2 will be considered pro-poor by all pro-poor evaluation function Ω2(g, z+) if

Equation (11.5) involves checking whether the average poverty gap of the initial distribution is greater than that in the later distribution when a distribution is normalized by (1 + g) over the range of poverty lines [0, z+]. The generalized Lorenz curve can be used to check alternatively. Second-order relatively pro-poor condition is if and only if p ∈ [0, F2(1 + g) z+)].

Through Eq. (11.6), one can compute the growth rates of the cumulative incomes of proportions p of the poorest and compare these growth rates withg. The ratio of mean income is 1 + g. Condition (11.6) helps us to check whether the Lorenz curve for y2 is above that of y1 for the range of p ∈ [0, F2(1 + g) z+)].

4.1.2 Absolute Pro-Poor Measurements

Absolute pro-poorness is calculated by comparing the absolute change in the income (or consumption) of the poor to some standard, denoted by a and usually set to zero. A change in income of the poor is good if it raises living standard of the poor people (Ravallion and Chen 2003). Therefore, the absolute axiom requires that if y + a = y′, then W(y, y′,a,z) = 0.

The formal definition of first-order absolute pro-poor evaluation functions \( {\tilde{\varOmega}}^1\left(a,{z}^{+}\right) \) comprises all functions W(., . , a, z) and needs to satisfy the population, anonymity, focus, monotonicity, normalization and absolute axioms, for which z ≤ z+.

Then a movement from y1 to y2 will be considered as first-order absolutely pro-poor, i.e. pro-poor by all evaluation functions W(., . , a, z) which are members of \( {\tilde{\varOmega}}^1\left(a,{z}^{+}\right) \) if and only if

Alternatively, the first-order absolute pro-poor can be measured by using the quantiles values for all p ∈ [0,F1(z+):

A similar condition holds good for the evaluation of absolute second-order pro-poorness. These assessments mainly depend on the \( {\tilde{\varOmega}}^2\left(a,{z}^{+}\right) \) class of indices, i.e. similarly to \( {\tilde{\varOmega}}^1\left(a,{z}^{+}\right) \). The second-order absolutely pro-poor is defined by

A sufficient condition for (11.9) is

4.1.3 Data Used

Urban MPCE from 61st round in 2004–2005, 66th round in 2009–2010 and 68th round in 2011–2012 are used for the analysis. Table 11.6 shows that real urban MPCE increased from Rs 326.8 to Rs 413.53 in the periods of 2005–2012, which accounts for about 27% growth rate.

4.1.4 Empirical Results

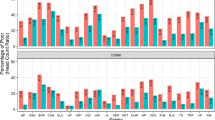

The Distributive Analysis Stata Package (DASP) developed by Araar and Duclos (2007) has been used for the empirical analysis. Figure 11.1 shows that the distribution of MPCE improved in the periods 2004–2005 to 2011–2012 as density curves shift to the right. Figure 11.2 and Table 11.3 show marginal increase in inequality in the periods 2004–2005 to 2011–2012. Figures 11.3 and 11.4 and the results in Table 11.3 recommend that absolute poverty, as measured by the headcount and poverty gap indices, had decreased in the years 2004–2005 to 2011–2012.

The first-order absolute and relative urban pro-poorness are calculated and presented in Figs. 11.5, 11.6, 11.7, 11.8, 11.9 and 11.10.Footnote 5 The absolute and relative pro-poor growth using the first-order and second-order approaches are presented in Table 11.5.

The top line of Fig. 11.5 presents the sample estimates of

For the difference between 2004–2005 and 2009–2010, the dotted bottom curve is the upper bound of the one-sided confidence interval:

As \( {\varDelta}^1(z)-\sigma {\hat{\varDelta}}^s{(z)}^{\zeta \left(\theta \right)}<0 \)in Fig. 11.5 is found accurate mostly for all reasonable poverty lines, it can be concluded that the growth was absolutely pro-poor in the years 2004–2005 to 2009–2010. The urban poverty line was Rs 860 in 2009–2010 (GOI 2014). It is clear from Fig. 11.5 that in Rs 860, the upper bound of the confidence interval for ∆1(z) is negative, and this indicates that growth was absolutely pro-poor for the periods 2004–2005 to 2009–2010. Similar results are obtained for the periods of 2009–2010 to 2011–2012. Figure 11.6 shows that the change in distribution was first-order absolutely pro-poor. The upper bound of the confidence interval for Δ1(z) is negative (the official urban poverty line was Rs 1000 in 2011–2012).

Figure 11.7 shows the test of pro-poorness for the years 2004–2005 to 2011–2012. The results show that the distributive change was first-order absolutely pro-poor. The lower bound of the confidence interval for P2011 − 12(z; α = 0) − P2004 − 05(z; α = 0) is negative for any reasonable poverty line. The official poverty lines estimated were Rs 579 in 2004–2005, Rs 860 in 209–2010 and Rs 1000 in 2011–2012.

The test of relative pro-poorness is calculated and presented in Figs. 11.8, 11.9 and 11.10. The sample estimates of P2009 − 10((1 + g)z; α = 0) − P2004 − 05 (z; α = 0) of distributive movement during the periods 2004–2005 to 2009–2010 were not first-order relatively pro-poor (Fig. 11.8). Also the confidence interval around the sample estimates makes it clear (Fig. 11.8) that the observed differences P2009 − 10((1 + g)z; α = 0) − P2004 − 05 (z; α = 0) are not statistically significant over a wide range of bottom poverty lines, i.e. the upper bounds of the one-sided confidence intervals extended above the zero line for z between Rs 400 and Rs 1200 rupees when tested for all urban India. The first-order relative pro-poor condition is not satisfied at 95% statistical confidence.

Figure 11.9 measures the relative pro-poorness for the years 2009–2010 to 2011–2012. The confidence interval of the sample estimates P2011 − 12((1 + g)z; α = 0) − P2009 − 10 (z; α = 0) is below zero for z after around Rs 700 and indicates no robust first-order relative pro-poorness. The test of second-order relative pro-poorness indicates a very strong anti-relative pro-poorness as the sample estimate of P2011 − 12((1 + g)z; α = 0) − P2009 − 10 (z; α = 0) is positive for z after around Rs 200. This supports the anti-relative pro-poor urban economic growth between 2009–2010 and 2011–2012.

Finally, Fig. 11.10 tests the first-order relative pro-poorness for the years 2004–2005 to 2011–2012. The confidence interval of the sample estimates of P2011 − 12((1 + g)z; α = 0) − P2004 − 05 (z; α = 0) is not always below zero, and it is positive between the ranges of Rs 300 and Rs 700. The robust result of anti-relative pro-poorness is calculated by testing the second-order relative pro-poorness, as the confidence interval is not below zero for any reasonable poverty line selected. Results are considered robust as no difference was found while testing first-order and second-order approaches for absolute and relative pro-poor judgements for the entire categories of urban India. Therefore, we conclude that India’s urban economic growth has been absolutely pro-poor but relatively anti-poor between the periods 2004–2005 to 2009–2010, 2009–2010 to 2011–2012 and 2004–2005 to 2011–2012. Table 11.7 summarizes the calculated results.

5 Conclusions

This chapter seeks to assess the pro-poorness of urban economic growth based on theoretical development by Duclos (2009) and Araar et al. (2007, 2009). As income data is not readily available for India, MPCE data provided by NSS for the years 2004–2005, 2009–2010 and 2011–2012 is used for analysis in this study.

The calculated poverty and inequality indices show that groups like ‘casual worker’, ‘not literate’, ‘scheduled tribes’, ‘scheduled castes’ and ‘other religion’ suffer higher levels of poverty than other groups. In contrast, groups like ‘postgraduate and above’, ‘graduate’, ‘diploma’ and ‘regular wage/salary earners’ have a lower level of poverty rate. Most importantly, the inequality level is high for groups like ‘other household type’, ‘other religion group’, ‘adult’, ‘those who have postgraduate and above level education’ and ‘male’. The extent of inequality is low for groups ‘not literate’, ‘middle-class’ educated people, ‘scheduled castes’, ‘casual labour’ and ‘those who passed primary-level’ education. The calculated results indicate that India’s urban economic growth has been absolutely pro-poor in general but relatively anti-poor in the years between 2004–2005 and 2009–2010, 2009–2010 and 2011–2012 and 2004–2005 and 2011–2012.

Notes

- 1.

For an overview of the various approaches to defining “pro-poor growth”, see Ravallion (2004).

- 2.

The details about URP, MRP and MMRP can be found in Tripathi (2013c) and NSS report on consumption expenditure. Though URP- or MRP-based consumption data is available for all the periods (61st, 66th and 68th NSS round surveys on consumer expenditure), MMRP-based consumption data is available only for the 66th and 68th NSS rounds.

- 3.

Latest Expert Committee headed by Dr. Rangarajan has considered MMRP-based MPCE to estimate poverty in India. However, MMRP-based consumption expenditure is available 2009–2010 onwards only.

- 4.

- 5.

The graphs that were generated from testing the second-order approach for absolute and relative pro-poor growth are presented here in the interests of space but available from the author.

References

Araar, A. (2012). Pro-Poor Growth in Andean Countries (Working Paper No. 12-25). CIRP EE.

Araar, A., & Duclos, J.-Y. (2007). DASP: Distributive Analysis Stata Package. PEP, World Bank, UNDP and Université Laval.

Araar, A., Duclos, J.-Y., Audet, M., & Makdissi, P. (2007). Has Mexican growth been pro-poor? Social Perspectives, 9, 17–47.

Araar, A., Duclos, J.-Y., Audet, M., & Makdissi, P. (2009). Testing for pro-poorness of growth, with an application to Mexico. Review of Income and Wealth, 55, 853–881.

Balasubramanian, P., & Ravindran, T. K. S. (2012). Pro-poor maternity benefit schemes and rural women: Findings from Tamil Nadu. Economic and Political Weekly, 47, 19–22.

Bhagat, R. B. (2010). Internal migration in India: Are the underprivileged migrating more? Asia Pacific Population Journal, 25, 31–49.

Bhagat, R. B. (2014). Urban migration trends, challenges and opportunities In India. Back ground paper of World Migration Report 2015, International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Datt, G., & Ravallion, M. (2009). Has India’s economic growth become more pro-poor in the wake of economic reforms? (Policy Research Working Paper No. 5103). World Bank, Washington, DC.

Davis, K. (1951). The population of India and Pakistan. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Deaton, A., & Kozel, V. (2005). Data and Dogma: The great Indian poverty debate. The World Bank Research Observer, 20, 177–200.

Dev, S. M. (2002). Pro-poor growth in India: What do we know about the employment effects of growth 1980–2000? (Working Paper No. 161). Overseas Development Institute.

Duclos, J.-Y. (2009). What is pro-poor? Social Choice and Welfare, 32(1), 37–58.

Government of India. (2009). Report of the expert group to review the methodology for estimation of poverty. New Delhi: Planning Commission.

Government of India. (2014). Report of the expert group to review the methodology for measurement of poverty. New Delhi: Planning Commission.

Liu, Y., & Barrett, C. B. (2013). Heterogeneous pro-poor targeting in the national rural employment guarantee scheme. Economic and Political Weekly, 48, 46–53.

McKinsey Global Institute. (2010). India’s urban awakening: Building inclusive cities, sustaining economic growth. San Francisco: McKinsey Global Institute.

Motiram, S., & Naraparaju, K. (2015). Growth and deprivation in India: What does recent evidence suggest on “Inclusiveness”? Oxford Development Studies, 43, 145–164.

National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO). (2006). 61st Round of household schedule 1.0 on Consumer Expenditure Survey data. Department of Statistics, Government of India.

National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO). (2011). 66th Round of household schedule 1.0 on Consumer Expenditure Survey data. Department of Statistics, Government of India.

National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO). (2013). 68th Round of household schedule 1.0 on Consumer Expenditure Survey data. Department of Statistics, Government of India.

Ravallion, M. (2000). What is needed for a more pro-poor growth process in India? Economic and Political Weekly, 35, 1089–1093.

Ravallion, M. (2004). Pro-poor growth: A primer (Policy Research Working Paper No. 3242). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Ravallion, M., & Chen, S. (2003). Measuring pro-poor growth. Economics Letters, 78, 93–99.

Ravallion, M., & Datt, G. (1999). When is growth pro-poor? Evidence from the diverse experience of India’s states (Policy Research Working Paper No. 2263). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2012). The price of inequality. London: Penguin Group.

Tripathi, S. (2013a). Do large agglomerations lead to economic growth? Evidence from urban India. Review of Urban and Regional Development Studies, 25, 176–200.

Tripathi, S. (2013b). Does higher economic growth reduce poverty and increase inequality? Evidence from urban India. Indian Journal for Human Development, 7, 109–137.

Tripathi, S. (2013c). Has urban economic growth in Post-Reform India been pro-poor between 1993–94 and 2009–10? (MPRA Paper 52336). Germany: University Library of Munich.

Tripathi, S. (2015). Determinants of large city slum incidence in India: A cross-sectional study. Poverty and Public Policy, 7, 22–43.

United Nations. (2014). World urbanization prospects: The 2014 revision, highlights. New York: United Nations, Population Database, Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

World Bank. (2011). Perspectives on poverty in India: Stylized facts from survey data. Washington, DC: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent.

ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned.

By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term "country" in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area.

Open Access This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 IGO license (CC BY-NC 3.0 IGO)http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/igo/. By using the content of this publication, you agree to be bound by the terms of this license. For attribution and permissions, please read the provisions and terms of use at https://www.adb.org/terms-use#openaccess.

This CC license does not apply to non-ADB copyright materials in this publication. If the material is attributed to another source, please contact the copyright owner or publisher of that source for permission to reproduce it. ADB cannot be held liable for any claims that arise as a result of your use of the material. Please contact pubsmarketing@adb.org if you have questions or comments with respect to content, or if you wish to obtain copyright permission for your intended use that does not fall within these terms, or for permission to use the ADB logo.

Copyright information

© 2019 Asian Development Bank

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Tripathi, S. (2019). Distribution of Urban Economic Growth in Post-reform India: An Empirical Assessment. In: Jayanthakumaran, K., Verma, R., Wan, G., Wilson, E. (eds) Internal Migration, Urbanization and Poverty in Asia: Dynamics and Interrelationships . Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1537-4_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1537-4_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-1536-7

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-1537-4

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)