Abstract

In this chapter, we explore the idea that wh-conditionals are interrogative conditionals.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

Three points need mentioning: first, Fine situation semantics of counterfactuals is not concerned with donkey binding but aims at providing a general theory of conditionals just as Stalnaker/Lewis/Kratzer—his main motivation for using situations is to invalidate substitution of logically equivalent antecedents and to validate simplification of disjunctive antecedents. Second, Fine situation-semantics and Kratzer (2012) situation-semantics have many differences (Fine ). But these differences are not relevant for our purposes so we choose to work with Kratzer formulation. Some terminology: whenever Fine says s is a p-state or s exactly verifies p, Kratzer says s exemplifies p. Whenever Fine says s inexactly verifies p, Kratzer says p is true in s (and sometimes we will say s supports p). Finally, to make another simplification, we will talk about exemplifying situations and minimal situations interchangeably, which is justified in our case for we are not going to talk about propositions that are divisive (such as propositions involve mass nouns and negative noun phrases). Standard definition of minimality based on part-of applies for now, but will be revised later.

- 2.

Formally, \(w \models A> C\; if \;u \Vert \!\!\!>\!C\) whenever \(t \Vert \!\!\!-\!A\) and \(t\rightarrow _w u\) (Fine 2012: 237), where > is the counterafactual symbol, \(\Vert \!-\) exact verification, \( \Vert \!\!\!>\) inexact verification, and \(t \rightarrow _{w} u\) means extending t to u according to facts (cf. Kratzer premise set) in w.

- 3.

Two points need mentioning: First, we need the outmost min because we have decided to choose Kratzer-style non-exact situation semantics and classical \(\wedge \). If we were to choose Fine-style exact situation semantics and non-classical \(\wedge \), the min would not be necessary. A non-classical situation semantics \(\wedge \) looks like this: s verifies \(A\wedge B\) iff s is the fusion \(s{_1}\sqcup s{_2}\) of a state \(s_1\) that verifies A and a state \(s_2\) that verifies B. Second, for simplicity, we are making a version of the Limit Assumption and the Unique Assumption (Stalnaker 1968); that is, for any \(s{*}\) there is exactly one maximal premise set that is compatible with p; we write (the conjunction of) the maximal premise set as \(C_{s*}\).

- 4.

- 5.

We use small capitals to refer to situations. Zhangsan-invited-John-Mary-&-Lisi-invited-John-Mary-Sue is the situation that exemplifies/minimally-supports the proposition that Zhangsan invited John and Mary, and Lisi invited John, Mary and Sue.

- 6.

min \(_\#\) is related to one of the two aspects of minimality—the individual minimality—discussed in Van Benthem (1989). Individual minimality itself comes from Logic Programming (Lloyd 2012). For instance, Prolog programs are supposed to ‘contain no individuals/objects except for those which are explicitly named in the language of the program’ (Van Benthem 1989: 334).

- 7.

Formalizing \(\textsc {No.Old}\) is doable. First, we take the set of situations that support the presuppositions of \(Q_A\) and \(Q_C\)—\(\{ s: \textsc {pre}(Q_A)(s) \wedge \textsc {pre}(Q_A)(s)\}\). We then apply min \(_\#\) to the set as what we did to \(S{_{13}}\); this gives us the unit set \( \{\textsc {Zs-inivted-Ls- \& -Ls-invited-Zs}\} \) =min \(_\#\{ s: \textsc {pre}(Q_A)(s) \wedge \textsc {pre}(Q_A)(s)\}\). Finally, \(\textsc {No.Old}\) in the case of \(S{_{13}}\) requires that none of the situations in \(S{_{13}}\) contain a subsituation that itself is a subsituation of any situation in min \(_\#\{ s: \textsc {pre}(Q_A)(s) \wedge \textsc {pre}(Q_A)(s)\}\). This is complicated, and I believe an intuitive understanding of \(\textsc {No.Old}\) suffices.

- 8.

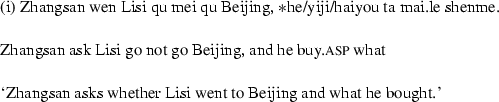

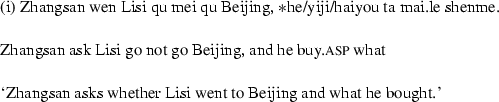

Here is an example:

- 9.

Our account is compatible with other ways of capturing the mention-some reading of questions, such as by appealing to pragmatic principles or partial answers. See Dayal (2016: \(Sect.\,\) 3) for relevant discussion.

References

Beck, S. 2012. Pluractional comparisons. Linguistics and Philosophy 35 (1): 57–110.

Beck, S., and H. Rullmann. 1999. A flexible approach to exhaustivity in questions. Natural Language Semantics 7 (3): 249–298.

Berman, S. 1987. Situation-based semantics for adverbs of quantification. In Studies in semantics, vol. 12, ed. J. Blevins, and A. Vainikka, 46–68., University of Massachusetts Occasional Papers in Linguistics Amherst: GLSA, University of Massachusetts.

Cheng, L.L., and C.J. Huang. 1996. Two types of donkey sentences. Natural Language Semantics 4 (2): 121–163.

Chierchia, G., and H.-C. Liao. 2014. Where do chinese wh-items fit? In Epistemic indefinites: Exploring modality beyond the verbal domain.

Chierchia, G. 2013. Logic in grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dayal, V. 1996. Locality in wh Quantification. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Dayal, V. 2016. Questions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elbourne, P.D. 2005. Situations and individuals. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Fine, K. 2012. Counterfactuals without possible worlds. The Journal of Philosophy.

Fine, K. Truthmaker semantics. In Blackwell companion to the philosophy of language. Blackwell. To appear.

Groenendijk, J., and M. Stokhof. 1982. Semantic analysis of wh-complements. Linguistics and Philosophy 5 (2): 175–233.

Haida, A. 2008. The indefiniteness and focusing of wh-words. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory 18.

Hamblin, C.L. 1973. Questions in Montague English. Foundations of Language 10: 41–53.

Heim, I. 1990. E-type pronouns and donkey anaphora. Linguistics and Philosophy.

Heim, I. 1994. Interrogative semantics and Karttunen’s semantics for know. In Proceedings of IATL 1.

Huang, C.-T.J. 1982. Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar. PhD thesis, MIT, Cambridge.

Huang, Y. 2010. On the form and meaning of Chinese bare conditionals: Not just whatever. PhD thesis, The University of Texas, Austin.

Karttunen, L., and S. Peters. 1976. What indirect questions conventionally implicate. In CLS 11.

Karttunen, L. 1977. Syntax and semantics of questions. Linguistics and Philosophy 1 (1): 3–44.

Kiss, K.É. 1995. Introduction. In Discourse configurational languages, ed. K.É. Kiss.

Kratzer, A. 1979. Conditional necessity and possibility. In Semantics from different points of view, 117–147. Springer.

Kratzer, A. 1981a. The notional category of modality. In Words, worlds, and contexts, 38–74.

Kratzer, A. 1981b. Partition and revision: The semantics of counterfactuals. Journal of Philosophical Logic 10 (2): 201–206.

Kratzer, A. 2012. Modals and conditionals. vol. 36. Oxford University Press.

Kratzer, A. 2014. Situations in natural language semantics. In The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, ed. E.N. Zalta. Spring. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/situations-semantics/.

Lewis, D. 1973. Counterfactuals. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lewis, D. 1981. Ordering semantics and premise semantics for counterfactuals. Journal of Philosophical Logic 10 (2): 217–234.

Lloyd, J.W. 2012. Foundations of logic programming. Springer Science & Business Media.

Reinhart, T. 1997. Quantifier scope: How labor is divided between qr and choice functions. Linguistics and Philosophy 20 (4): 335–397.

Rooth, M. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1 (1).

Rothstein, S. 1995. Adverbial quantification over events. Natural Language Semantics 3 (1): 1–31.

Schwarz, B. 1998. Reduced conditionals in german: Event quantification and definiteness. Natural Language Semantics 6 (3): 271–301.

Stalnaker, R. 1968. A theory of conditionals. In Studies in logical theory, ed. N. Rescher., American Philosophical Quarterly Monograph Series 2 Oxford: Blackwell.

Stalnaker, R. 1975. Indicative conditionals. Philosophia.

Van Benthem, J. 1989. Semantic parallels in natural language and computation. In Logic colloquium. Cranada 1987, ed. E. HD, 331–375. Elservier.

von Fintel, K. 1994. Restrictions on quantifier domains. PhD thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

von Fintel, K. 2004. A minimal theory of adverbial quantification. In Context dependence in the analysis of linguistic meaning, ed. H.K.B. Partee, 137–175. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Peking University Press and Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Liu, M. (2018). Proposal-A: wh-Conditionals as Interrogative Conditionals. In: Varieties of Alternatives. Frontiers in Chinese Linguistics, vol 3. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6208-7_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6208-7_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-6207-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-6208-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)