Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

A Tungussic language spoken in the southern part of Russian Far East. In (2), mi is a simultaneous.converb (sim.cvb) (Baek 2016), a verbal suffix indicating subordination.

- 2.

The names antecedent and consequent as well as wh-conditional presuppose that we are taking wh-conditionals to be a type of conditional (Cheng and Huang 1996; Lin 1996; Chierchia 2000), which however is debatable (Huang 2010; Crain and Luo 2011). We nevertheless have to start somewhere. I will in this section assume following Cheng and Huang; Lin; Chierchia that wh-conditionals are conditionals, postponing discussion to later sections.

- 3.

A fact that I will have to leave to future research.

- 4.

We construe the term PSI very broadly as including negative polarity items like ever, free choice items like any/irgendein as well as epistemic indefinites, following Chierchia (2013).

- 5.

De is a modification marker that appears between a noun and its modifiers (adjectives, possessors, relative clauses, etc.) in Mandarin.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

- 9.

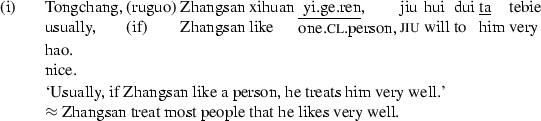

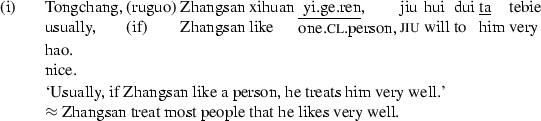

This is to assume that adverbs of quantification are able (at least sometimes) to quantify over individuals (eg. Lewis 1975). I will adopt this view for concreteness. The fact (to be shown in this subsection) that wh-conditionals do not exhibit real quantificational variability then suggests their antecedents are \(\sigma \)-closed. There is another approach that treats quantificational adverbs as exclusively (in any context) quantifying over situations (eg. Heim 1990; von Fintel 2004; Elbourne 2005). But in the situation-approach, we still need to distinguish between whether it is an indefinite in the restriction \(Q_{adv}[\lambda s.\exists x\ldots ][\lambda s.\ldots ]\) or a definite \(Q_{adv}[\lambda s.\sigma x\ldots ][\lambda s.\ldots ]\) (these two presumably have different behaviors). The discussion in this subsection according to this view can be taken to suggest that wh-conditionals belong to the latter category.

- 10.

Typical Mandarin donkey sentences having indefinites in the antecedent and pronouns in the consequent behave the same:

- 11.

- 12.

- 13.

To illustrate, a \(s_1\) where Zhangsan invites John is strictly smaller than a \(s_2\) where Zhangsan invites John and Mary, and both \(s_1\) and \(s_2\) satisfy \(\lambda s.\textsc {in}(\sigma x.\textsf {invite}(\textsf {zs},x,s),s)\). They satisfy the condition by being a situation where the individual(s) Zhangsan invites in that situation is in that situation.

- 14.

The corresponding English FRs seem to behave the same. If that’s true, what I suggest below as an explanation to the contrast between (16) and (19) applies to English FRs as well.

- 15.

English FRs seem to behave the same: whichever two win the game should buy me a drink presupposes that there will be exactly two winners.

- 16.

In (31), I suppress the situation variable (motivated in the previous subsection to handle adverbs of quantification) in the absence of adverbial quantifiers. I also treat na liang.ge.ren ‘which two.cl.persons’ in the consequent as an unanalyzed variable X. We could also take the consequent-na liang.ge.ren to be \(X\wedge \textsf {2.persons}(X)\), in which case the entire consequent will come out as \(\lambda X.\textsf {invite}(\textsf {ls},X)\wedge \textsf {2.persons}(X)\) and the resulting wh-conditional \(\textsf {invite}(\textsf {L},\sigma X.(\textsf {invite}(\textsf {zs},X)\wedge 2.\textsf {persons}(X)))\wedge \textsf {2.persons}(\sigma X.(\textsf {invite}(\textsf {zs},X)\wedge 2.\textsf {persons}(X)))\). Since the second conjunct of this truth-condition is vacuously true, this is equivalent to (31).

- 17.

We write \(\sigma x.P(x)\) for \(\sigma (\lambda x.P(x))\) and don’t distinguish sets and their characteristic functions. We also use: and . to enclose presuppositions (Heim and Kratzer 1998).

- 18.

Actually the consequent also carries uniqueness: (28) presupposes that Lisi invites exactly 2 persons. This cannot be captured by the correlative analysis sketched in this subsection, but is related to the exhaustive flavor to be discussed in Sect. 5.4.6.

- 19.

I thank Simon Charlow for asking me to be explicit about this.

- 20.

For a dynamic analysis of uniqueness effects, see (Brasoveanu 2008).

- 21.

- 22.

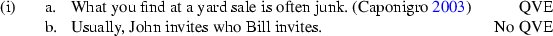

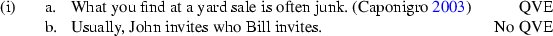

Chierchia and Caponigro (2013) makes this point for free relatives. To be fair, Caponigro (2003) discusses ways to constrain the distribution of existential free relatives. In particular, in Caponigro ’s analysis, free relatives are \(\lambda \)-abstracts/sets (with wh-words being set-restrictors) that undergo type-shift before combining with the matrix predicate. According to the ranking in Dayal (2004), existential shift is ranked lower than \(\sigma \)-shift, and thus existential free relatives are rare.

- 23.

The point is also stressed in Cheng and Huang (1996: \(Sect.\,\)6.1) as motivation for not adopting a correlative analysis for wh-conditionals.

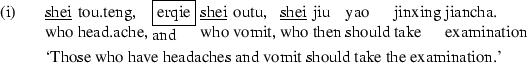

- 24.

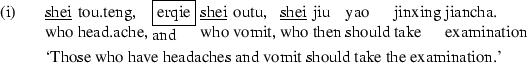

The judgment of (53-c) is not clear. I myself don’t like conjoining declarative clauses using yiji/haiyou; for me, a different and erqie has to be used, also shown in (53-c). In the literature, Lü (1980: 615) (page numbers from Lü 1998) says yiji can conjoin ‘clauses’, however, all of his examples use embedded questions. Finally, it seems that erqie (the one that conjoins clauses) is also able to participate in wh-conditionals, illustrated in (i).

What is surprising about (i) is its interpretation. Instead of collecting all individuals that have headaches or vomit as in (52), erqie seems to instruct us to collect individuals that both have headaches and vomit (again, the judgment is not stable). Since my argument in the main text relies on interactions between wh-phrases and the two connectives he and yiji/haiyou, I leave how erqie works and its interaction with wh-conditionals to another occasion.

- 25.

Lin works within the unselective binding paradigm, so he can talk about assignments of values to the whs in a wh-conditional and whether they co-refer. In the terms of a FR-based equative analysis where the wh-phrases are relative pronouns, the observation is that the antecedent and the consequent do not always co-refer.

- 26.

Hermione-Ron and Harry-Ginny are couples in Harry Potter.

- 27.

I thank an anonymous reviewer for SALT 26 for providing me with this example. The scenario in (56-b) (with the names N. Chomsky, M.A.K Halliday, Danny Fox, and J. R. Martin) is also due to the reviewer. Note that M.A.K Halliday and J. R. Martin are presumably famous functional syntacticians. Mary and John are assumed to be two random linguists, one a generative linguist, the other a functionalist.

- 28.

I thank Veneeta Dayal and Ivano Caponigro for discussion of this. My explanation of the asymmetry differs from how they would pursue the issue. Roughly, they would like to have a pragmatic story, where the antecedent and the consequent have different status in the information structure— for example, the entire antecedent could occupy a topic position, which might explain why it cannot be questioned. The explanation I will adopt however is a semantic one, which relies on the intuition that the consequent of a wh-conditional depends on its antecedent. Since you can answer a question by specifying what it depends on but not what it results in, the asymmetry (58)–(59) is explained. Details follow.

- 29.

Lin’s bare conditionals are just our wh-conditionals.

- 30.

The term ‘asymmetric’ has to be read loosely, not in its mathematical sense where an asymmetric relation R is such that\(\forall a, b(R(a,b)\rightarrow \lnot R(b,a))\). ‘depend on’ in the mathematical sense is neither symmetric nor asymmetric.

- 31.

I thank Gennaro Chierchia for urging me to explore this idea.

References

Aoun, J., and Y.-H.A. Li. 2003. Essays on the representational and derivational nature of grammar: The diversity of wh-constructions. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Baek, S. 2016. Tungusic from the perspective of areal linguistics: Focusing on the Bikin Dialect of Udihe. PhD thesis, Hokkaido University.

Beck, S., and H. Rullmann. 1999. A flexible approach to exhaustivity in questions. Natural Language Semantics 7 (3): 249–298.

Berman, S. 1994. On the semantics of WH-clauses. New York and London: Garland.

Brasoveanu, A. 2008. Donkey pluralities: plural information states versus non-atomic individuals. Linguistics and Philosophy 31: 123–209.

Bruening, B., and T. Tran. 2006. Wh-conditionals in vietnamese and chinese: against unselective binding. In Proceedings of the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society.

Caponigro, I. 2003. Free not to ask: On the semantics of free relatives and wh-words cross-linguistically. PhD thesis, UCLA.

Caponigro, I. 2004. The semantic contribution of wh-words and type shifts: Evidence from free relatives crosslinguistically. Semantics and Linguistic Theory 14: 38–55.

Carlson, G.N. 1977. A unified analysis of the english bare plural. Linguistics and Philosophy 1 (3): 413–457.

Champollion, L. 2010. Parts of a whole: Distributivity as a bridge between aspect and measurement. Ph.D thesis, University of Pennsylvania.

Chao, Y.R. 1968. A grammar of spoken Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cheng, L.L.S. 1997. On the typology of wh-questions. Taylor & Francis.

Cheng, L.L., and C.J. Huang. 1996. Two types of donkey sentences. Natural Language Semantics 4 (2): 121–163.

Cheung, C.C.H. 2006. The syntax and semantics of bare conditionals in chinese. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 11: 150–164.

Chierchia, G., and I. Caponigro 2013. Questions on questions and free relatives. In Handout for SuB 18.

Chierchia, G., and H.-C. Liao. 2014. Where do chinese wh-items fit?. In Epistemic indefinites: Exploring modality beyond the verbal domain.

Chierchia, G. 1998b. Reference to kinds across language. Natural Language Semantics 6 (4): 339–405.

Chierchia, G. 2000. Chinese conditionals and the theory of conditionals. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 9 (1): 1–54.

Chierchia, G. 2013. Logic in grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coppock, E., and D. Beaver. 2015. Definiteness and determinacy. Linguistics and Philosophy 38: 377–435.

Crain, S., and Q.-P. Luo. 2011. Identity and definiteness in chinese wh–conditionals. In Proceedings of SuB 15.

Dayal, V. 1991. The syntax and semantics of correlatives. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 9 (4): 637–686.

Dayal, V. 1995. Quantification in correlatives. In Quantification in natural languages: Springer.

Dayal, V. 1996. Locality in wh Quantification. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Dayal, V. 2004. Number marking and (in)definiteness in kind terms. Linguistics and Philosophy 27 (4): 393–450.

Dekker, P. 1993. Existential disclosure. Linguistics and Philosophy 16 (6): 561–587.

Elbourne, P.D. 2005. Situations and individuals. MIT Press Cambridge.

Fine, K. 2012. Counterfactuals without possible worlds. The Journal of Philosophy.

Heim, I. 1990. E-type pronouns and donkey anaphora. Linguistics and philosophy.

Heim, I. 1982. The semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases. PhD thesis, University of Massachusetts.

Heim, I., and A. Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in generative grammar. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hinterwimmer, S. 2013. Free relatives as kind-denoting terms. In Genericity, ed. A. Mari, C. Beyssade, and F.D. Prete. Oxford University Press.

Hinterwimmer, S. 2008. Q-Adverbs as selective binders. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Hole, D. 2004. Focus and background marking in Mandarin Chinese. London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon.

Horn, L.R. 1989. A natural history of negation. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Huang, Y. 2010. On the form and meaning of Chinese bare conditionals: Not just whatever. PhD thesis, The University of Texas at Austin.

Jacobson, P. 1995. On the quantificational force of english free relatives. In Quantification in natural languages, 451–486. Springer.

Kadmon, N. 1990. Uniqueness. Linguistics and Philosophy 13: 273–324.

Kamp, H. 1981. A theory of truth and semantic representation. In Formal methods in the study of language, ed. A. Groenendijk, T. Janssen, and M. Stokhof. Amsterdam: Mathematical Centre.

Karttunen, L. 1973. Presuppositions of compound sentences. Linguistic Inquiry 4: 167–193.

Kratzer, A. 1989. An investigation of the lumps of thought. Linguistics and philosophy 12 (5): 607–653.

Krifka, M. 1989. Nominal reference, temporal constitution and quantification in event semantics. In Semantics and contextual expressions, ed. R. Bartsch, J. van Benthem, and P. van Emde Boas, 75–115. Dordrecht: Foris.

Lasersohn, P. 1995. Plurality, conjunction and events. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer.

Lewis, D. 1973. Counterfactuals. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lewis, D. 1975. Adverbs of quantification. In Formal semantics of natural language, ed. E. Keenan. Cambridge University Press.

Li, C.N., and S.A. Thompson. (1981). Mandarin Chinese: A functional reference grammar. University of California Press.

Liao, H.-C. 2011. Alternatives and exhaustification: Non-interrogative uses of Chinese Wh-words. PhD thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge.

Lin, J.-W. 1996. Polarity licensing and wh-phrase quantification in Chinese. PhD thesis, University of Massachusetts.

Lin, J.-W. 1998. Distributivity in Chinese and its implications. Natural Language Semantics 6.

Lin, J.-W. 1999. Double quantification and the meaning of shenme ‘what’ in chinese bare conditionals. Linguistics and Philosophy 22 (6): 573–593.

Link, G. 1983. The logical analysis of plurals and mass terms: A lattice-theoretic approach. In Meaning use and interpretation of language, 302–323. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Lipták, A. (ed.). 2009. Correlatives cross-linguistically. John Benjamins Publishing.

Liu, M. 2017. Mandarin conditional conjunctions and only. Studies in Logic 10 (2): 45–61.

Lü, S. 1980. Xiandai hanyu babai ci [800 words of contemporary Chinese]. Shangwu Yinshuguan.

Luo, Q.-P., and S. Crain. 2011. Do chinese wh-conditionals have relatives in other languages? Language and Linguistics 12: 753–798.

Nikolaeva, I., and M. Tolskaya. 2001. A grammar of Udihe. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Partee, B.H. 1986. Noun phrase interpretation and type-shifting principles. In Studies in discourse representation theory and the theory of generalized quantifiers, ed. J. Groenendijk, D. de Jongh, and M. Stokhof, 143–153. Dordrecht: Foris.

Schwarzschild, R. 1996. Pluralities. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Sharvy, R. 1980. A more general theory of definite descriptions. The Philosophical Review 89: 607–624.

Stalnaker, R. 1968. A theory of conditionals. In Studies in logical theory, ed. N. Rescher., American Philosophical Quarterly Monograph Series 2 Oxford: Blackwell.

Sternefeld, W. 2009. Do free relative clauses have quantificational force? snippets.

Strawson, P.F. 1950. On referring. Mind 320–344.

von Fintel, K., D. Fox and S. Iatridou. 2014. Definiteness as maximal informativeness. In The art and craft of semantics: A Festschrift for Irene Heim, vol. 1, 165–174. MITWPL.

von Fintel, K. 2004. A minimal theory of adverbial quantification. In Context Dependence in the analysis of linguistic meaning, ed. H.K.B. Partee, 137–175. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Wang, X. 2016. The logical-grammatical features of the "Shenme\(\ldots \) Shenme" sentence and its deduction. Luojixue Yanjiu [Studies in Logic] 9 (1): 63–80.

Wen, B. 1997. ‘Donkey sentences’ in English and ‘wh\(\ldots \) wh’ construction in Chinese. Xiandai Waiyu 3: 1–13.

Wen, B. 1998. A relative analysis of Mandarin ‘wh-\(\ldots \) wh-’ construction. Modern Foreign Languages 4: 1–17.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Peking University Press and Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Liu, M. (2018). Mandarin wh-Conditionals: Challenges and Facts. In: Varieties of Alternatives. Frontiers in Chinese Linguistics, vol 3. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6208-7_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6208-7_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-6207-0

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-6208-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)