Abstract

The Courts in India have suggested that the process followed by the CCI for initiating an investigation of alleged abuse of dominance is merely a departmental inquiry and not adjudicatory in nature. This chapter, set in the backdrop of an investigation concerning alleged abuse of dominance in the ICT sector, observes the process adopted by CCI to initiate an investigation. This chapter illustrates that the practice adopted by CCI is more of adjudicatory in nature as opposed to what has been suggested by the Courts.

This chapter is a revised version of Working Paper Series No. 17002, which has greatly benefitted from presentation and discussion at ‘The Law and Economics of Patent Systems: A Conference of the Hoover Institution Working Group on Intellectual Property, Innovation, and Prosperity’ held on January 12–13, 2017, at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University and comments received from Mr. Richard Sousa, Research Fellow and Member of Hoover IP2, Working Group Steering Committee, Stanford University.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This chapter is premised on the recent judgement delivered by the Delhi High Court (henceforth “DHC”) in Ericsson v CCI. Footnote 1 This judgement looked at the jurisdiction of the Competition Commission of India (henceforth “CCI”) to investigate alleged abuse of dominance of a holder of standard essential patent (henceforth “SEP”). The jurisdiction of CCI, as suggested by the DHC is independent of any matter pending in a court of law and therefore, the CCI can continue to investigate abuse of dominance complaints.

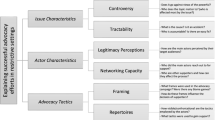

Trend of the nature of Parties in cases before CCI (The parties have been classified as Local, Foreign, Government and Unknown. Local parties are individuals of Indian nationality and companies registered in India. Companies such as AIR India, GAIL, NOIDA (state run entities) have been categorised as local parties. Parties have been categorized as foreign if one of the parties is a foreign entity. Departments of Indian government have been categorised as Government parties. In few instances government has been made a proforma party, and therefore classification as Government party has been disregarded. Anonymous and XYZ informants have been classified as Unknown parties.)

Trends in hearing the parties by CCI at the stage of Sections 26(1) and 26(2) (For the purpose of this study, a party is considered to be heard if the respective order states the same or if in the title clause, the respective party is said to be present in person or represented by a legal representative. If an order refers to written statements then it has been presumed that the opposite party has been heard. Informant are considered of been heard if apart from the initial information the commission considers the additional information, facts or data placed on record by the informant)

In the backdrop of an investigation concerning alleged abuse of dominance in the ICT sector, this chapter observes the process adopted by CCI to initiate such investigation.Footnote 2 The Supreme Court of India and other High Courts, although in non-ICT sectors, have provided some guidelines and interpretation about the nature of investigation undertaken by the CCI at the initial stage. The Courts in India have suggested that the process of initiating an investigation is merely a departmental inquiry and not adjudicatory in nature. Therefore, there is no need for the CCI to notify or hear any of the parties involved. The chapter shows that the practice adopted by CCI is different from what has been suggested by the Courts. Careful scrutiny of orders delivered by CCI in the last three years (2013–16) elaborates the ground realities that although there is no statutory requirement of informing the parties, increasingly parties are notified, and they have been allowed to present their submissions at the stage of deciding the course of an investigation. Relevant facts provided by the parties at the initial stage, including the complainant and the opposite party, are recorded, analyzed and relied upon at the time of deciding whether a particular complaint should be further investigated by the Director General (henceforth “DG”) (Section 26(1)) or dismissed altogether (Section 26(2)).

2 CCI v Ericsson: The Jurisdiction of CCI Upheld by Delhi High Court

The recent judgement involving CCI v Ericsson suggested a possible conflict and tension between the existing Patents and Competition regime in India.Footnote 3 In their argument, Ericsson contended that the existing Patents Act in India can handle all existing and future disputes involving an SEP holder and the licensee who is and will be using the patented technology.Footnote 4 The Patents Act, which has already the status of a special legislation, would eventually override the provisions (Competition Act) of a general legislation. With these arguments in place, Ericsson filed a writ petition under Article 226 of the Indian Constitution before the DHC. This writ petition challenged the role of CCI in a situation where there is a conflict between an SEP holder and the user of such patented technology. Upon receiving a complaint, the CCI under Section 26(1) of the Competition Act is empowered to initiate a detailed investigation particularly questioning alleged abuse of dominance of the holder of patented technology.

As a response to the writ petition, the CCI took the plea that any order of detailed investigation, against a holder of patented technology, is merely administrative in nature. Owing to its administrative nature, there is no scope of judicial review under Article 226 of the Indian Constitution.Footnote 5 In the process of substantiating their argument, CCI referred to the Supreme Court’s decision in Competition Commission of India v. Steel Authority of India Ltd. & Anr.Footnote 6 While judging a similar application of judicial review under Article 226 of the Indian Constitution, the Supreme Court in the Steel Authority of India case suggested that an order initiating a detailed investigation by the DG under Section 26(1) of the Competition Act was an administrative order and therefore, would not come within the ambit of an adjudicatory decision.Footnote 7 As a response to the plea taken by Ericsson in the DHC case, the CCI suggested that the provisions of both Acts i.e. The Patents and the Competition Act may be applied in a matter involving patent infringement and abuse of dominance without giving rise to any conflicting situation.Footnote 8

The DHC agreed with CCI’s line of argument and suggested that investigation undertaken by CCI concerning alleged abuse of dominance of a holder of patented technology may continue. This is despite the fact that a patent infringement matter is pending at the DHC. As a basis to their argument, the DHC suggested that both Acts have different objectives. With the objective of resolving competition issues in India, the Competition Act may continue to work independently of the Patent Acts. In fact, both legislations can act supplementary to each other.Footnote 9

As to the scope of Article 226, although the DHC suggested that the scope is wide, there are limitations as to the extent Courts can be involved in deciding its application.Footnote 10 The question of judicial review would arise only if the CCI has reached to the prima facie opinion concerning alleged abuse of dominance in a malafide way. However, a party filing a petition would not be denied a remedy under Article 226 only because of the existence of an alternative remedy.Footnote 11

The outcome of this judgement is important for more than one reason. It was the first instance when an Indian court was asked to decide on the role of CCI in a crucial matter relating to the high-priority ICT sector. There could be possible repercussion on the overall growth and development of the ICT sector, however, this chapter is not going to delve into assessing such repercussion. For the purpose of this chapter, we are going to concentrate on the developments surrounding orders of investigation by CCI in cases relating to abuse of dominance. We will investigate the ground realities as to the practice of CCI at the stage of communicating detailed orders of investigation based on complaints received under the Competition Act. Towards that end, relevant investigation orders and the processes followed in cases covering last three years have been considered.Footnote 12

3 Initial Investigation Orders by CCI

The CCI has been set up under Section 7 of the Competition Act. It consists of a Chairperson and six other members.Footnote 13 The DG who is appointed under Section 16 steers the process of investigating abuse of dominance inquiry initiated by the CCI. Duties and powers of the CCI have been assigned under Chapter IV of the Competition Act.Footnote 14

3.1 Abuse of Dominance Investigation Under the Competition Act

The complaint under Section 19(1), which precedes the process of investigation by the Commission (Chairperson and six members), may originate from either an informant, the central government, state government, statutory authority or as a result of a suo moto action taken up by the Commission.Footnote 15 Upon receiving a complaint, the Commission would decide on a prima facie case of abuse of dominance.Footnote 16 Based on the prima facie reading of the complaint the Commission may order the DG to initiate a detailed investigation (by an order under Section 26(1)) or dismiss the complaint altogether (by an order under Section 26(2)) under the Competition Act.Footnote 17

Table 1 represents all cases which were disposed of by passing orders either under Section 26(1) or Section 26(2). It suggests that majority of the complaints have been received from the informant. While the other source of complaints continue to be less, there is an extraordinary reliance on complaint filed by informants. The number of further orders of detailed investigation to the DG is lot less than the complaints that have been dismissed.

In the last three years the complaints have been mostly filed by individuals and companies of Indian origin. There is however a decrease in such complaints with the number of complaints slowly increasing from governmental agencies.Footnote 18 The parties against whom such complaints have been made are mostly persons and companies of Indian origin, however, there is a steady increase of complaints against foreign companies for abuse of dominance as well.Footnote 19

The orders suggesting further investigations against foreign companies have been in the range of 27%, while 65% of the total number of orders of investigation have been against persons and companies of Indian origin.Footnote 20 Most investigations against foreign companies have been in the agricultural and the mobile phone industry.Footnote 21

The Competition Act would not formally require the Commission to notify the informant or the opposite party or any other person before passing a formal order of investigation to the DG or at the time of dismissing a complaint.Footnote 22 This non-requirement, of course would not stop the Commission to call ‘any person’ or to call for any material that would help in deciding the prima facie case of abuse of dominance.Footnote 23

3.2 Prima Facie Order of Investigation: Guidelines from Non-ICT Cases

The Supreme Court in the Steel Authority of India judgement has given us some guidance about the nature of a prima facie order of investigation.Footnote 24 Following the existing structure of complaint under the Competition Act (Section 19(1) read along with Section 26(1)), Jindal Steel & Powers Ltd (henceforth “JSPL”/“the informant”) filed a complaint against Steel Authority of India (henceforth “SAIL”/“the opposite party”).Footnote 25 As a follow-up to the complaint received, the Commission asked the informant and the opposite party to furnish additional information.Footnote 26 Upon much deliberation, which included consideration of relevant records, hearing the representatives of JSPL, the Commission found a prima facie case of abuse against SAIL and extended the matter to the DG for a detailed investigation.Footnote 27 Contesting the appeal filed by the opposite party before the Competition Appellate Tribunal (henceforth “COMPAT”), the Commission suggested that the order instructing the DG to conduct an investigation “…was a direction simpliciter to conduct investigation and thus was not an order appealable within the meaning of [s]ection 53A of the [Competition] Act”.Footnote 28 The COMPAT held that the appeal was maintainable owing to the principles of natural justice.Footnote 29

The Supreme Court of India was entrusted with the task of deciding whether the appeal was maintainable in a case where the DG was asked to investigate abuse of dominance. While delivering the judgement, the Supreme Court reflected upon the prima facie order of investigation.

-

1.

The nature of order: departmental inquiry and not adjudicatory

The Supreme Court was of the opinion that the prima facie order of investigation from the Commission to the DG was nothing more than a departmental inquiry and it is inquisitorial in nature.Footnote 30 This order would not be more than an administrative action and not adjudicatory in nature.Footnote 31 Regardless of nature of the order, the Commission at the time of framing its opinion and forwarding a case to the DG for further investigation should record the reasons.Footnote 32 Recording of reasons follow the traits of administrative law and do not depend on the stage of ongoing investigation.

The Supreme Court went on to suggest that the order of initiating a detailed investigation would not bring upon any civil consequences on the opposite party in question. This argument posed by Supreme Court was followed in a decision of the Madras High Court as well.Footnote 33 From the perspective of keeping an order of investigation confidential, the Supreme Court relied upon the application of Section 57 of the Competition Act read with regulation 35. The combination provides assurance that strict confidentiality procedures would be followed at the time of investigating any matter before the Commission.Footnote 34

As a result, any order given under Section 26(1) to the DG to conduct detailed investigation is a departmental inquiry. This is unlike 26(2) where an appeal is maintainable as a follow-up action to the complaint dismissed by the Commission.Footnote 35

-

2.

Notifying parties and application of natural justice

Going by the interpretation of Section 26(1), the Supreme Court suggested that there was no formal requirement to notify the parties at a time when matters are being investigated upon at the preliminary stage.Footnote 36 This was in response to SAIL’s claim suggesting that parties should be notified about the developments at the prima facie stage.Footnote 37 Unlike Section 26(2), there was no reason to make an assumption about the requirement of a notice. This is primarily because any such requirement would have been explicitly spelled out in the provision itself.Footnote 38 There exists a discretionary power with the Commission to notify parties by calling them at the prima facie stage, however that discretionary power does not become an:

…absolute proposition of law that in all cases, at all stages and in all event the right to notice [a] hearing is a mandatory requirement of principles of natural justice… Different laws have provided for exclusion of principles of natural justice at different stages, particularly, at the initial stage of the proceedings and such laws have been upheld by this court. [Furthermore] such exclusion is founded on larger public interest and is for compelling and valid reasons, the courts have declined to entertain such a challenge.Footnote 39

The non-requirement of notifying the parties connects with the nature of the inquiry at the initial stage. The act of forming prima facie opinion and passing onto the DG for detailed investigation has already been established as an administrative inquiry.Footnote 40 In order to handle complaints of abuse of dominance in an expeditious manner, the Supreme Court further suggested that there is no requirement of notice and following such step would not be violating the principle of natural justice.Footnote 41 The direction of investigation under 26(1) is merely a ‘preparatory [step]’ and not a ‘decision making process’.Footnote 42

Although the Supreme Court suggested that natural justice requirement need not be fulfilled at the prima facie stage, the Commission on its own accord did inform the opposite party about the complaint filed by the informant. In fact, the opposite party did file their response documents to the Commission. Going by the process followed, the Commission had even asked the informant to file additional information. Further, the Commission had given the informant some additional time to furnish them.Footnote 43 While the opposite party was asked to submit comments in response to the complaint filed by the informant, the opposite party’s request to extend the time to file its comments was declined.Footnote 44

It is evident that the overarching requirements of natural justice has been followed by the Commission i.e. notification and a chance to the opposite party to present its response—Audi alteram partem.Footnote 45 Even the Madras High Court referred to the CCI’s practise of hearing both parties at the preliminary stage.Footnote 46 Interestingly, the Madras High Court noted that the issue of natural justice was never raised and argued before it.Footnote 47 In fact, with the plea of natural justice in place the court could have decided the case in a different way.

The Supreme Court and other courts have clearly established that the order of detailed investigation can be passed onto to the DG without notifying the parties. It will be however interesting to observe the process followed by the Commission while handling prima facie orders of investigation.Footnote 48

4 The Practice Followed by CCI in Prima Facie Orders and the ICT Sector

It is important to understand the extent of reliance on the information received from the informant as a part of the complaint. Of course, keeping just within the confines of a departmental inquiry and not hearing either the complainant or the opposite party would not be helpful to decide whether to proceed or dismiss the complaint altogether.

While the Supreme Court and the Madras High Court have talked about the statutory non-requirement of notice, the practice of the Commission has been generally different. In fact, there is enough evidence to suggest that at the prima facie stage the Commission in the last three years have informed at least one of the parties. There is a steady decrease in cases where none of the parties have been called at a stage of deciding the course of investigation. Starting with the trend of inviting only the complainant, there is an emerging trend of inviting the opposite party as well.Footnote 49 This trend is also true when complaints have been dismissed under Section 26(2). In the case of dismissed complaints, primarily the informant has been heard with a growing trend of both parties having been called in recent times.

So far, the three matters considered by the Commission in the ICT sector reflects a similar trend.Footnote 50 Regardless of not having a statutory requirement, the Commission subsequent to receiving complaints have accepted submissions from either the informant or from both parties.Footnote 51 The process adopted by the Commission provides a substantive route of inquiry, which goes beyond just deciding the course of an investigation based on a complaint.Footnote 52 By allowing submission of additional information and hearing advocates at the prima facie stage, the nature of departmental inquiry has changed considerably.Footnote 53 Even in the form, which is used for filing a complaint, there is a column for including name and address of the counsel or other authorized person.Footnote 54 Inclusion of these details is indicative of further opportunity provided to the parties who are involved in the complaint. Further, this form is not a result of a schedule and therefore, gives enough freedom to the Commission to engage with the parties at the prima facie stage.Footnote 55 Going by the indications, the process adopted by the Commission at the time of deciding the course of investigation has somewhat become quasi-adjudicatory. This situation is different from the position adopted by the Supreme Court and the Madras High Court.

5 Information Considered at the Prima Facie Stage in ICT Sector

One of the earlier cases in this sector involved Micromax and Ericsson. Micromax filed a complaint against Ericsson alleging abuse of dominance under Section 19(1)(a).Footnote 56 Contrary to the requirement of licensing the patented technology, which has also become a standard, as per FRAND (fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory) terms, the complainant suggested that the royalty demanded by Ericsson was unfair, discriminatory, exorbitant and excessive.Footnote 57 Further, Micromax alleged that Ericsson divulged details of the infringed patents and terms of FRAND license only after Micromax had signed a non-disclosure agreement (henceforth “NDA”).Footnote 58 According to Micromax, signing of an NDA also substantiated their claim that Ericsson was charging different rates of royalty and there was no uniformity in this regard.Footnote 59

It was alleged that the method adopted by Ericsson to decide the rate of royalty was incorrect. Micromax suggested that this rate should be based on the chipset or the technology instead of the final value of a phone that uses such technology.

Through written submission Ericsson suggested that Micromax has been inconsistent in the whole process.Footnote 60 While they had agreed to pay royalty before the DHC, Micromax alleged unfair and exorbitant royalty rate before the CCI.Footnote 61 On an overall note Ericsson challenged the jurisdiction of the CCI and specifically suggested that fixing of royalty rates should not come under the realms of CCI. Further, they noted that seeking an injunction due to infringement of a patent, which has also become an essential patent for a standard, is not a sign of abuse of dominance.Footnote 62

As a part of the order, the Commission held that by virtue of the technology owned by Ericsson they would be in a dominant position as compared to present and prospective licensees.Footnote 63 The Commission in its order suggested that Ericsson had violated the agreed FRAND norms. This is because they did not contest the allegation that they were indulging in different rates of royalty. So far as the royalty base is concerned, the Commission selected patented technology over the final product (mobile phone).Footnote 64 The argument in the order suggested that “charging of two different license fees per unit phone for use of the same technology prima facie is discriminatory and also reflects excessive pricing vis-à-vis high cost phones”.Footnote 65 Following these observations, the CCI ordered the DG to carry out detailed investigation.Footnote 66

Similar to the Ericsson-Micromax, there was another order of investigation against Ericsson.Footnote 67 This time it involved Intex Technologies. The informant following similar arguments as in the Micromax order suggested that Ericsson used unfair licensing terms in their Global Patent Licensing Agreement (henceforth “GPLA”).Footnote 68 They cited that the jurisdiction clause in GLPA was limited to the laws of Sweden.Footnote 69 Upon receiving the complaint Ericsson modified the jurisdiction clause to the laws of Singapore.Footnote 70 There was similar complaint about signing of an NDA agreement connected to the non-release of commercial terms, details of infringement and other licensing conditions.Footnote 71 Intex alleged issues of royalty stacking and patent hold-up in their complaint with a further claim of excessive and discriminatory pricing on Ericsson’s part.Footnote 72 Ericsson suggested that they had broadly offered uniform royalty rate to all prospective licensees.Footnote 73 Strangely, the argument of an unwilling licensee posed by Ericsson against Lava, which was accepted by the DHC, was not used before the CCI at the time of responding to the complaints made by either Micromax or Intex.Footnote 74

The CCI took serious exception and suggested that “NDA thrust upon the consumers by the [opposite party] strengthens this doubt after NDA, each of the user of SEPs is unable to know the terms of royalty of other users.”Footnote 75 This approach is against the “…spirit of… FRAND terms…”.Footnote 76 The CCI also under similar grounds found a prima facie case of abuse of dominance against Ericsson in the iBall matter.Footnote 77

There is no limitation on the kind of information that an informant can share with CCI as a part of the complaint. The standard form used for filing complaints includes: “Introduction/brief of the facts giving rise to filing of the information”; “Jurisdiction of CCI”; “Details of alleged contravention of the provisions of the Competition Act, 2002” and “Detailed facts of the case”.Footnote 78 There are considerable debates surrounding the arguments adopted by the CCI at the time of initializing the investigation.Footnote 79 It is beyond the scope of this chapter to look at those debates.

The matters so far investigated upon by the CCI in the ICT sector are few in number. Further to the process adopted by CCI at the stage of deciding the course of investigation, there is a strong possibility that they may want to consider all relevant facts as a part of submission by an opposite party. As in other cases and following the trend, it is likely that in case of future complaints in the ICT sector, the Commission would listen to both the complainant and the opposite party at the prima facie stage. With increasing representations from the SEP holders, CCI would have a range of information before issuing the detailed order of investigation. Looking beyond the shores of India we have certain guidelines emanating from Huawei v ZTE.Footnote 80 It essentially looks at the pre-licensing behaviour of both the licensor and licensee. To some extent these pre-licensing behaviour have been considered by the CCI at the prima facie stage and may be in future, provide additional guidance in assessing prima facie case of abuse of dominance.

6 Conclusion

It is difficult to estimate the outcome of an investigation initiated by CCI at a given instance when all relevant information have been provided. This is beyond the scope of this chapter. From what has been observed, CCI is willing to go into details of the submissions made even at the prima facie stage and appropriately giving, although to a lesser extent to the SEP holder, the parties a chance to represent themselves.

Notes

- 1.

Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ) v. Competition Commission of India, Case W.P.(C) 464/2014 & CM Nos.911/2014 & 915/2014 and W.P.(C) 1006/2014 & CM Nos.2037/2014 & 2040/2014 dt. 30.03.2016 (hereinafter Ericsson v CCI).

- 2.

For a detailed discussion on issues relating to jurisdiction and competition authorities, see SHUBHA GHOSH & DANIEL SOKOL, FRAND IN INDIA, COMPETITION POLICY AND REGULATION IN INDIA: A ECONOMIC APPROACH (Forthcoming).

- 3.

Ericsson v CCI. In about three cases involving Ericsson in India it was suggested that Ericsson failed to offer the use of SEPs on FRAND terms. FRAND commitment for Ericsson arises under clause 6 of the European Telecommunication Standard Institute (ETSI) IPR policy.

- 4.

Patents Act, 1970, Chapter XVI covers working of patents, compulsory licensing and revocation of patents. § 84(7) of the Patents Act includes grant of a compulsory licence in the case where a patent holder refuses to grant licences on reasonable terms. Ericsson cited cases like (General Manager Telecom v. M. Krishnan & Anr., JT 2009 11 SC 690; Chairman, Thiruvalluvar Transport Corporation v. Consumer Protection Council, 1995 2 SCC 479). Ericsson also suggested that § 4 of the Competition Act, 2002 was not applicable with regard to licensing of SEPs. This was because Ericsson was not an ‘enterprise’ as per § 2(h) of the Act. Further licensing of patents did not amount to the sale of goods and services and as a result would not fall within the ambit of the Competition Act.

- 5.

Following § 60 of the Act with reference to (Union of India v. Competition Commission of India, AIR 2012 Del 66; M/S Fair Air Engineering Pvt. Ltd. v. N K Modi, 1996 6 SCC 385) the provision of competition law will prevail in case of inconsistency with any other law.

- 6.

((2010) 10 SCC 744).

- 7.

Union of India v. Competition Commission of India, AIR 2012 Del 66; M/S Fair Air Engineering Pvt. Ltd. v. N K Modi, 1996 6 SCC 385.

- 8.

Gujarat Urja Vikash Nigam Ltd. v. Essar Power Ltd., 2008 4 SCC 755.

- 9.

Ericsson v CCI, at 165.

- 10.

Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ) v. Competition Commission of India, Case W.P.(C) 464/2014 & CM Nos.911/2014 & 915/2014 and W.P.(C) 1006/2014 & CM Nos.2037/2014 & 2040/2014 dt. 30.03.2016; Id., at 68; Dwarka Nath v. Income Tax Officer, 1965 57 ITR 349 SC [70]; State of A.P v. P.V Hanumantha Rao, 2003 10 SCC 121; Tata Cellular v. Union of India, AIR 1996 SC 11.

- 11.

Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ) v. Competition Commission of India, Case W.P.(C) 464/2014 & CM Nos.911/2014 & 915/2014 and W.P.(C) 1006/2014 & CM Nos.2037/2014 & 2040/2014 dt. 30.03.2016 [81].

- 12.

For the purpose of this chapter, all the relevant orders made available by CCI on its website under the heads ‘Section 26(1)’ and ‘Section 26(2)’ passed between (i) 1st April, 2013 to 31st March, 2014; (ii) 1st April, 2014 to 31st March, 2015; and (iii) 1st April, 2015 to 31st March, 2016 were considered. Some of the orders were combined orders dealing with multiple cases. Therefore, in this chapter the number of cases have been mentioned instead of the number of orders.

- 13.

Competition Act, 2002, § 8.

- 14.

Id., §18-39.

- 15.

For the purpose of this chapter we have not considered the suo moto actions taken by the commission; Id., §19; Competition Commission of India (General) Regulations, 2009, Regs 10-13, 23 & 49; CCI, How to File Information?, http://cci.gov.in/sites/default/files/cci_pdf/HowToFileInformation.pdf.

- 16.

Competition Act, § 3 & 4 (deal with prohibition of anti-competitive agreements and prohibition of abuse of dominant position respectively).

- 17.

Decision based on § 26(2) is appealable, Competition Act, 2002, § 53B (1) & 53A (1) (a).

- 18.

Figure 1.

- 19.

Id.

- 20.

Figure 2.

- 21.

Figure 2.

- 22.

Competition Commission of India v Steel Authority of India Ltd. and Another., (2010) 10 SCC 744 [11].

- 23.

Under regulation 17(2), the Commission has the power to call not only the informant but any party including the affected party, Competition Commission of India (General) Regulations, 2009, Regs. 17 (2) & 44 (1).

- 24.

Competition Commission of India v Steel Authority of India Ltd. and Anr., (2010) 10 SCC 744.

- 25.

JSPL invoked the provisions of § 19 read with § 26 (1) of the Competition Act, 2002 by providing information to the CCI alleging that SAIL had inter alia entered into an exclusive supply agreement with Indian Railways, for supply of long rails. JSPL alleged that SAIL had abused its dominant position in the market and deprived others of fair competition and therefore, acted contrary to § 3 (4) and 4 (1) of the Competition Act, Case No. 11 of 2009, CCI.

- 26.

After receiving the complaint, the Commission had a meeting with representatives of JSPL and also fixed a conference with representatives of SAIL. On 19th November, 2009 a notice was issued to SAIL enclosing all information submitted by JSPL directing SAIL to submit its comments by 8th December, 2009 in respect of the information received by the Commission. On 8th December when the matter was heard, SAIL wanted an extension of time by six weeks to file its comments and for conference with the Commission. However, without hearing SAIL, the Commission passed an order under Section 26(1) on 08.12.2009 directing the DG to investigate the case (2010) 10 SCC 744 [8]; Order dated. 20.12.2011, Case No. 11/2009, CCI [3], available at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/64217260/.

- 27.

Ericsson v CCI; (2010) 10 SCC 744 [8], Order dated 20.12.2011, Case No. 11/2009, Competition Commission of India, at 3, https://indiankanoon.org/doc/64217260/.

- 28.

Order dated 20.12.2011, Case No. 11/2009, Competition Commission of India [4], https://indiankanoon.org/doc/64217260/; (As per the Finance Bill, 2017, effectively from 26th May, 2017, the COMPAT has ceased to exist and NCLAT is now the Appellate Authority under the Competition Act, 2002,) Part XIV of Chapter VI of the Finance Act, 2017. Accordingly, § 2(ba) & 53A of the Competition Act; (2010) 10 SCC 744 [9].

- 29.

Competition Act, 2002, § 53A; SAIL also suggested that, since § 53A suggests that appeal is allowed on any direction issued or decision made or order passed by the Commission. The contention was that use of “or” in the provision would also include the direction of the Commission to the DG under § 26(1). Hence this direction would be appealable, (2010) 10 SCC 744 [29]. This argument was not considered by the Supreme Court. The court suggested that the Statute has clearly laid down under § 53A, the grounds of appeal and there, unlike § 26(2), § 26(1) has been omitted. It stated that the “..right to appeal is a creation of statute and it does require application of rule of plain construction. Such provision should neither be construed too strictly nor too liberally, if given either of these extreme interpretations, it is bound to adversely affect the legislative object as well as hamper the proceedings before the appropriate forum”, (2010) 10 SCC 744 [35].

- 30.

“Investigating power granted to the administrative agencies normally is inquisitorial in nature”, Krishna Swami v Union of India [1992] 4 SCC 605.

- 31.

(2010) 10 SCC 744 [28].

- 32.

This is contrary to the situations where the Commission acts in the adjudicatory capacity. Competition Act, 2002, § 19, 20, 26, 27, 31, 33; (2010) 10 SCC 744 [24]; The court went on to say “…Even in a direction… the Commission is expected to [support his action] based on some reasoning … not detailed. [However] when “…decisions and orders, which are not directions simpliciter and determining the rights of the parties should be well reasoned.” (2010) 10 SCC 744.

- 33.

Chettinad International Coal v. The Competition Commission of India and others, W.P.No.7233 of 2016, Madras High Court, Order dated 29.03. 2016; In this case a writ petition was filed questioning whether an order made under Section 26(1) can be challenged, [18]. Under Art. 226 of the Indian Constitution a writ remedy is an extra –ordinary power that is vested with the High Court that examine the correctness or orders passed by forums subordinate to it [21].

- 34.

Competition Act, 2002, § 57; Competition Commission of India (General) Regulations, 2009, Reg. 35.

- 35.

(2010) 10 SCC 744 [28].

- 36.

(2010) 10 SCC 744 [61].

- 37.

(2010) 10 SCC 744 [53].

- 38.

Id. Another example is the requirement of notice under Reg. 14(7)(f) and Reg. 17(2). The secretary of the Commission is empowered to serve the notice of the date of the ordinary meeting of the Commission to consider the information or reference or document to decide if there exists a prima facie case, Competition Commission of India (General) Regulations, 2009, Reg. 14(7)(f); The Commission may invite the information provider and such other person as is necessary for the preliminary conference, Competition Commission of India (General) Regulations, 2009, Reg. 17(2).

- 39.

(2010) 10 SCC 744 [63].

- 40.

Krishna Swami v Union of India [1992] 4 SCC 605.

- 41.

(2010) 10 SCC 744 [27].

- 42.

Competition Commission of India v Steel Authority of India Ltd. and Anr., (2010) 10 SCC 744.

- 43.

(2010) 10 SCC 744 [8].

- 44.

Gujarat Urja Vikash Nigam Ltd. v. Essar Power Ltd., 2008 4 SCC 755.

- 45.

Audi Alteram partem states that a decision cannot stand unless the person directly affected by it was given a fair opportunity both to state his case and to know and answer the other side’s case, R v Chief Constable of North Wales Police, ex p Evans (1982) 1 WLR 1155 (HL); An order which infringes a fundamental freedom passed in violation of the audi alteram partem rule is a nullity, Nowabkhan Abbaskhan v State of Gujarat, AIR 1974 SC 1471.

- 46.

Chettinad International Coal v. The Competition Commission of India and others, W.P.No.7233 of 2016, Madras High Court, Order dated. 29.03.2016.

- 47.

Krishna Swami v Union of India [1992] 4 SCC 605.

- 48.

The COMPAT which has now been dissolved in a recent matter in the same context suggested that “…the Commission cannot make detailed examination of the allegations contained in the information or reference, evaluate/analyse the evidence produced with the reference or information in the form of documents and record its findings on the merits of the issue relating to violation of Section 3 and/or 4 of the Act because that exercise can be done only after receiving the investigation report [from the DG]”, Gujarat Industries Power Company Limited v. CCI and GAIL, Appeal No. 3 of 2016, COMPAT, Order dated 28.11.2016.

- 49.

Figure 3.

- 50.

Case No. 50/2013 pursuant to information filed by Micromax Informatics Limited, Case No. 76/2013 pursuant to information filed by Intex Technologies (India) Limited, Case No. 04 of 2015 pursuant to information filed by M/s Best IT World (India) Private Limited (iBall), all against Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ), Competition Commission of India.

- 51.

Case No. 50/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 12.11.2013 [10]; Case No. 76/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 16.01.2014 [10]; Case No. 04 of 2015, Competition Commission of India, Order dated. 12.05.2015, at 7.

- 52.

CCI, How To File Information?, http://cci.gov.in/sites/default/files/cci_pdf/HowToFileInformation.pdf.

- 53.

Infra 4.3 & Annexures; Competition Commission of India (General) Regulations, 2009, Reg. 17 (2) & 44 (1).

- 54.

CCI, supra note 55.

- 55.

Competition Commission of India (Procedure in regard to the Transaction of Business, etc.) Regulations, 2011, Form I in Schedule II.

- 56.

Case No. 50/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 12.11.2013.

- 57.

See SHUBHA GHOSH & DANIEL SOKOL, FRAND IN INDIA, COMPETITION POLICY AND REGULATION IN INDIA: A ECONOMIC APPROACH (Forthcoming); Ericsson v CCI; Gujarat Urja Vikash Nigam Ltd. v. Essar Power Ltd., 2008 4 SCC 755.

- 58.

Ericsson v CCI; Micromax made a request for details of the FRAND license in the month of July, 2011. A Non-Disclosure Agreement was executed on 16.01.2012. The terms of the FRAND licences were disclosed to the Micromax on 05.11.2012, Id., [4]; Ericsson thereafter on 4th March, 2013, filed a patent infringement suit, Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ) v Mercury Electronics & Another, CS (OS) No. 442/2013, Delhi High Court. An ex parte interim order against Micromax was passed, Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ) v Mercury Electronics & Another, CS (OS) No. 442 of 2013, Order dated. 06.12.2013. As per an interim arrangement Micromax had deposited 29.45 crores towards payment of royalty as on 31.05.2013, Case No. 50/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 12.11.2013, at 7.

- 59.

Case No. 50/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 12.11.2013, at 8.

- 60.

Id.

- 61.

Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ) v Mercury Electronics & Anr, CS (OS) No. 442 of 2013, Order dated 19.03.2013; Case No. 50/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 12.11.2013.

- 62.

Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ) v Competition Commission of India & Another W.P.(C) No. 464/2014.

- 63.

Case No. 50/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 12.11.2013; Competition Act, § 3 & 4.

- 64.

CCI favored a royalty base based on smallest saleable patent practicing unit (SSPPU) as opposed to entire market value rule (EMVR).

- 65.

Case No. 50/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 12.11.2013, at 17.

- 66.

Id., at 19 & 20.

- 67.

Case No. 76/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 16.01.2014.

- 68.

Id., at 6.

- 69.

Id.

- 70.

Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ) v. Competition Commission of India, Case W.P.(C) 464/2014 & CM Nos.911/2014 & 915/2014 and W.P.(C) 1006/2014 & CM Nos.2037/2014 & 2040/2014 dt. 30.03.2016 [13.2].

- 71.

Case No. 76/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 16.01.2014, at 7.

- 72.

Id., at 8.

- 73.

Id., at 7.

- 74.

Telefonktiebolaget LM Ericsson (Publ) v Lava International Ltd, I.A. Nos.5768/2015 & 16011/2015 in CS(OS) No.764/2015, Judgment dated 10.06.2016; Case No. 50/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 12.11.2013.; Case No. 76/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 16.01.2014.

- 75.

Case No. 76/2013, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 16.01.2014, at 17.

- 76.

Id.

- 77.

Case No. 04/2015, Competition Commission of India, Order dated 12.05.2015.

- 78.

CCI, supra note 55.

- 79.

Gregory Sidak, The Meaning of FRAND, Part I: Royalties, 9(4) J. COMP’N. L & ECON. 931–1055 (2013); Mark Lemley & Carl Shapiro, Patent Holdup and Royalty Stacking, 85 Texas L. REV. 1992 (2007); Kirti Gupta, Technology Standards and Competition in the Mobile Wireless Industry, 22 GEO. MASON L. REV. 865 (2014-2015); Kristian Henningsson, Injunctions for Standard-Essential Patents Under FRAND Commitment: A Balanced, Royalty-Oriented Approach, 47 INT’L. REV. INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY & COMP’N. L. 438 (2016); Anne Layne-Farrar, et al., Preventing Patent Hold Up: An Economic Assessment of Ex Ante Licensing Negotiations in Standard Setting, 37 AIPLA Q. J. 445 (2009); Gregory Sidak, Injunctive Relief and the FRAND Commitment in the United States, in CAMBRIDGE HANDBOOK OF TECHNICAL STANDARDIZATION LAW, VOL. 1: ANTITRUST AND PATENTS, (Jorge L. Contreras, (ed.), forthcoming 2017), https://www.criterioneconomics.com/docs/injunctive-relief-and-the-frand-commitment.pdf; Gregory Sidak FRAND in India, in CAMBRIDGE HANDBOOK OF TECHNICAL STANDARDIZATION LAW, VOL. 1: ANTITRUST AND PATENTS, (Jorge L. Contreras, (ed), forthcoming 2017), https://www.criterioneconomics.com/docs/frand-in-india.pdf.

- 80.

Case C-170/13, Huawei Techs. Co. v. ZTE Corp. (July 16, 2015), http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?text=&docid=165911&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=603775.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Additional information

Disclosure:

Opinions expressed in the chapter are independent of any research grants received from governmental, intergovernmental and private organisations. The authors’ opinions are personal and are based upon their research findings and do not reflect the opinions of their institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gupta, I., Devaiah, V.H., Jain, D.A. (2018). CCI’s Investigation of Abuse of Dominance: Adjudicatory Traits in Prima Facie Opinion. In: Bharadwaj, A., Devaiah, V., Gupta, I. (eds) Complications and Quandaries in the ICT Sector. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6011-3_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6011-3_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-6010-6

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-6011-3

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)