Abstract

Patents on standardized technologies are being issued with increasing frequency, and large multinational firms based in developed economies hold the majority of these patents. As a result, firms from less-developed economies with sparse patent holdings may be disadvantaged in both domestic and foreign markets. While protectionist governmental policies can address these disparities, such measures are potentially contrary to international treaty obligations and often unsuccessful in the long term. An alternative approach involves greater participation in international SSOs by firms from less-developed economies. This increased participation is likely to benefit such firms both in terms of technology development, strengthening of patent positions, and influence over SSO policies. To facilitate increased participation, subsidies may be required from local governments, NGOs, multinational organizations or SSOs themselves.

This chapter has benefitted from presentation and discussion at the Workshop on Mega-Regionalism: New Challenges for Trade and Innovation (MCTI), Honolulu, Hawaii, USA—January 20–21, 2016, and from helpful comments and discussion with Ashish Bharadwaj, Dieter Ernst and Brian Kahin.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Today’s technology product markets, particularly in the information and communications technology (henceforth “ICT”) sector, are inherently international. Products designed in California may be assembled in Taiwan from parts sourced from Korea, Germany and Malaysia for sale to end consumers in India. The global character of technology markets underscores the importance of technical interoperability standards such as those enabling wireless networking (Wi-Fi, Bluetooth), wireless telecommunications (4G LTE), digital media storage (DVD, SDRAM) and digital content encoding (MP3/MP4). These standards enable products and components manufactured by different vendors to work together without customization or firm-to-firm interaction. Stakeholders affected by technology interoperability standards span the globe, from product designers to manufacturers to consumers. This chapter considers the impact of patents on international technical standardization activities. In particular, it assesses the impact that patents have on individual firm behavior and intra-firm dynamics in the context of international standard-setting, and evaluates available options to reduce disparities between large patent holders and firms from less-developed economies.

2 Standards and the International Standard-Setting Landscape

While many health, safety and environmental standards are developed by governmental agencies, the vast majority of interoperability standards originate in the private sector.Footnote 1 In the U.S., there is an express governmental preference for privately-developed standards over government-developed standards,Footnote 2 and elsewhere this preference has generally been supported by the market. Some widely adopted interoperability standards (e.g., Microsoft’s .doc and Adobe’s PDF electronic document formats) are single-firm proprietary formats (de facto standards). Over the past two decades, however, most successful interoperability standards have been developed by groups of firms that collaborate within voluntary associations known as standards-development organizations or standards-setting organizations (henceforth “SSOs”). The resulting standards are often referred to as “voluntary consensus standards”, which will be the principal focus of this chapter.

SSOs vary greatly in size and composition. The European Commission identifies three broad categories of SSO:Footnote 3

-

(1)

those that are formally recognized by governmental bodies. These include:

-

International groups [e.g., the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Telecommunications Union (ITU)],

-

regional groups [e.g., the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI)], and

-

national groups [e.g., Germany’s Deutsches Institut für Normung (DIN), the Japanese Standards Association (JSA), China’s National Institute for Standardization (CNIS) and the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS)].Footnote 4

-

-

(2)

“quasi-formal” groups that are typically large international organizations that share many of the characteristics of formally recognized groups [e.g., the IEEE Standards Association, ASTM International and the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF)], and

-

(3)

smaller, privately-organized consortia (also known as special interest groups or fora), including groups such as the Bluetooth SIG, HDMI Forum, USB Forum and hundreds of others.Footnote 5

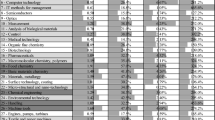

Table 1 lists a number of widely-adopted ICT standards and the organizations in which they were developed.

3 Firm-Level Participation in Standard-Setting

Firm-level participation in SSOs varies according to the type and nature of the SSO. ISO, probably the most prominent Category 1 SSO, allows participation solely on a national basis, so that each member state has a delegation that represents its interests at the SSO. Criteria for participation in a national delegation are determined at the national level. The U.S. representative to ISO, for example, is ANSI. Other Category 1 SSOs may limit participation to firms and institutions engaged in business in a particular geographic area. For example, the members of the European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardization (CENELEC) comprise the national electrical standardization committees of each European state. Other Category 1 SSOs, such as ETSI, open membership to all interested parties, but offer different membership categories and benefits to those within the region of focus (Europe, in the case of ETSI).

In contrast, Category 2 SSOs are generally open to all interested parties on an equal basis. Participation depends on firms’ interest in the relevant area of standardization, as well as its ability to bear personnel, travel and technology costs associated with SSO participation. It is no surprise that large global technology firms participate in upwards of fifty or more different SSOs, with the largest involved in more than one hundred SSOs each.Footnote 6 Participation in large, international SSOs in the ICT sector has traditionally been international in character, with representation from firms and institutions based in North America, Europe, Oceania, Japan, Korea and India. Over the last decade, Chinese firms have dramatically increased their participation in international SSOs, in some sectors surpassing participation from all countries other than the U.S.Footnote 7 Despite recent gains by China, SSO participation by firms in less-developed countries, particularly in Latin America and Africa, has remained at low levels.

Category 3 SSOs or consortia are usually formed by small groups of firms interested in developing a specific technology or standard. Often these “founder” or “sponsor” firms hold patents relevant to the technology in question.Footnote 8 Such founders are often large multinationals with substantial patent portfolios, but may also include smaller, specialized firms focusing on the target technology area.

4 Patents and Standards

4.1 Patenting Standards

Standards are sets of protocols and technical descriptions of product features enabling interoperability. While standards themselves are not patentable, products that are compliant with the technical requirements of standards (often referred to as standards-compliant products) generally satisfy the statutory requirements for patent protection. The owners of patents covering these standardized technologies (referred to as standard-essential patents or “SEPs”) are often the firms and institutions that employ individuals who make particular inventive contributions to standards. Some of these contributions may be made jointly and owned by multiple firms, but in most cases firms individually submit technical contributions to the standard-setting process and own the resulting SEPs.

Because standards documents are often quite lengthy and complex, sometimes running to hundreds or thousands of pages, multiple inventive concepts are frequently embodied in the same standard, leading to the possibility of multiple patents covering any given standard. For example, Blind et al. report large numbers of patent familiesFootnote 9 declared to be essential to various standards including WCDMA (1000 patent families), 4G LTE (1000 patent families), MPEG-2 and MPEG-4 (160 patent families), optical disc drive standards (2200 patent families), and DVB-H (30 patent families).

Ordinarily, if the vendor of a product that infringes a patent is unable, or does not wish, to obtain a license on the terms offered by the patent holder, that vendor has three choices: to stop selling the infringing product, to design around the patent, or do neither and risk liability as an infringer. With standards-compliant products, however, designing around the patent may be impossible or economically infeasible. Moreover, once a standard is approved and released by an SSO, market participants may make significant investments in plant, equipment and labor, based on anticipated implementation of the standard in products (a situation often referred to as lock-in).Footnote 10 In such cases, the cost of switching from the standardized technology to an alternative technology may be prohibitive, thereby increasing the patent holder’s leverage in any ensuing negotiation over licensing rates. This phenomenon has been termed patent “hold-up” and is discussed extensively in the literature.Footnote 11

As noted above, complex technological products may implement dozens, if not hundreds, of standards each of which may be covered by hundreds or thousands of patents. As such, the aggregation of royalty demands by multiple patent holders could lead to cost-prohibitive burdens on implementing standards-compliant products. This situation is sometimes referred to as “royalty stacking”.Footnote 12

4.2 SSO Patent Policies

Over the past two decades, SSOs have responded to the increasing number of patents covering standardized technologies and the perceived threats of patent hold-up and stacking by adopting a series of policy measures intended to address these concerns. SSO patent policies today fall into two general categories: disclosure policies and licensing policies, and often include elements of both. Disclosure policies typically require participants in the standards development process to disclose SEPs that they hold. Licensing policies typically require that participants grant manufacturers of standardized products licenses under their SEPs on terms that are “fair, reasonable and nondiscriminatory” (henceforth “FRAND”) or royalty-free (henceforth “RF”).

These commitments purport to assure manufacturers that they will be able to obtain licenses (which may sometimes involve a payment) to sell standards-compliant products covered by SEPs. Perhaps, in part, because FRAND commitments require relatively little administrative overhead to enact, their use has become widespread among SSOs.Footnote 13 Nevertheless, a consistent, practical, and readily enforceable definition of FRAND has proven difficult to achieve. No SSO defines precisely what FRAND means, and many affirmatively disclaim any role in establishing, reviewing, or assessing the reasonableness of FRAND licensing terms. This lack of certainty has contributed to recent litigation over FRAND commitments,Footnote 14 and leaves most of the details of licensing arrangements to bilateral negotiations among patent holders and potential licensees.

5 Impact of Patents on International Participation in Standard-Setting

5.1 Patenting by SSO Participants

Over the past two decades there has been a sharp increase in patenting within certain technology standardization sectors, particularly wireless telecommunications.Footnote 15 In addition, a core group of firms in the telecommunications sector accounts for the large majority of patent filings covering ICT standards. These firms include Qualcomm, InterDigital, LG Electronics, Nokia, Samsung, Ericsson and Motorola.Footnote 16 In addition, researchers have observed a rapid increase in patenting activity by Huawei in the area of Internet standardization.Footnote 17 These statistics suggest that patenting behavior is not concentrated among firms of any one country, but is distributed at least among firms based in the major developed economies [U.S. (Qualcomm, InterDigital and Motorola), Korea (LG and Samsung), Europe (Nokia and Ericsson), and China (Huawei)].Footnote 18

When considering levels of patent acquisition, it is important to note that a firm’s home jurisdiction is relatively immaterial to the jurisdictions in which it seeks and obtains patents. That is, a large firm with a global market is likely to seek patents in all major markets, no matter where it is based. Thus, in 2014, the ten firms to which the greatest number of U.S. patents were awarded were: IBM (US), Samsung (Korea), Canon (Japan), Sony (Japan), Microsoft (US), Toshiba (Japan), Qualcomm (US), Google (US), LG (Korea) and Panasonic (Japan).Footnote 19 It is likely that a comparable distribution exists in most other jurisdictions, with at most a modest “head start” advantage for local firms. Thus, in India, research conducted by the author and the Centre for Internet and Society has found that nearly 100% of Indian patents covering mobile device technologies are owned by foreign companies.Footnote 20 These are, by and large, the same major international technology firms that are active throughout the world.

These findings suggest that in terms of standard-essential patents (and, most likely, all patents), firms can be classified as either “Haves” or “Have-nots”. The Haves are generally large multinational technology-focused firms based in North America, Europe and the Asia Pacific economies. The “Have-Nots” are all others. It is important to note that not all firms based in these key jurisdictions are Haves. Smaller firms and new market entrants in developed economies may also be Have-Nots. Likewise, not all firms based in developing nations are, or must remain, Have-Nots. A key example is China-based Huawei which, in the span of just a few years, rose from insignificance to prominence in the area of Internet standardization and related patent holdings.Footnote 21 Other large firms in China, India, Brazil and other emerging economies may also be situated to invest the resources necessary to increase their patent portfolios in this manner. However, it appears that most firms in these jurisdictions are likely to be classified as Have-Nots.

5.2 Patent Licensing Dynamics

As noted above, most SSOs require that their participants license SEPs to product manufacturers on terms that are either FRAND or RF. Thus, at least as to standardized technologies, patent acquisition and enforcement is unlikely to result in outright exclusion of competitors from a market. However, in markets characterized by FRAND (as opposed to RF) licensing, transactions are not always smooth or equitable, particularly in relation to transactions between Have and Have-Not firms.

The situation often plays out as follows: a standard is developed at an international SSO. Firms that participate in the SSO obtain patents covering the standard throughout the world. The standard then becomes implemented in products that are sold globally. By the time firms in less-developed countries become aware of the potential for sales of such products in their own countries (possibly with locally-attractive features, lower costs or domestically-sourced components), the basic product technologies have already been patented by foreign Have firms. Local Have-Nots must thus seek licenses from foreign Haves in order to manufacture standardized products for their domestic markets. The royalties sought by foreign patent-holding firms, while arguably reasonable on an international basis, may be viewed as excessive in local markets. The royalty burden owed to foreign firms can thus be viewed as inequitable by local firms and governments, particularly if foreign Have firms enter the market and compete with the local Have-Nots.Footnote 22 Such sentiments surfaced in China during the development of 2G wireless telecommunications standards, leading to China’s adoption of a domestic 2G standard known as TD-SCDMA, which enjoyed limited success.Footnote 23

The perception of unfairness can be exacerbated when foreign firms actively enforce their patents against local market participants in their domestic markets. This situation has recently occurred in India where, over the past three years, multinational telecommunications vendor Ericsson has brought patent infringement suits against several Indian and Chinese handset vendors serving the domestic Indian market.Footnote 24

6 Potential Responses

There are several potential responses, both public and private, to the perceived inequity implicit in foreign Have firms’ practices relating to the patenting and licensing of technical interoperability standards to domestic firms in less-developed countries. In many cases, these responses are not mutually exclusive and may co-exist within a country or region. The principal categories of such responses are considered below:

6.1 Embrace the Status Quo

Action is required to address a situation only if a problem exists. There are many who would argue that the current patent imbalance between Have and Have-Not firms is a natural result of market-based global trading. The situation is no different than it is in many other industries including pharmaceuticals, automotive and aviation, in which a handful of firms from developed countries dominate the market. In such a market, all firms have the potential to succeed based on superior innovation and technical skill.

This potential is particularly salient in the area of technical standardization, in which SSO participation is, in many cases, open to all interested organizations irrespective of national origin. The success of firms from small countries [e.g., Philips (Netherlands), Nokia (Finland) and Ericsson (Sweden)], and from developing economies [e.g., Huawei and ZTE (China)] demonstrates that the “club” of successful market entrants is not limited to firms from the largest developed economies. Thus, special measures designed to create a greater balance between the interests of Haves and Have-Nots could be misguided and counterproductive.

6.2 Adopt Protectionist Measures

When a government perceives that its domestic producers are being disadvantaged by foreign interests, a natural reaction is to implement regulations, and undertake enforcement actions, intended to protect the local industry. Of course, expressly protectionist regulation generally flies in the face of widely-adopted international treaty obligations such as the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (the TRIPS Agreement),Footnote 25 as well as more recent bilateral and multilateral trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).Footnote 26 Nevertheless, protectionist measures that target the actions of foreign patent holders may be disguised as prohibitions of unfair business practices and anticompetitive behavior, and may remain on the books for years before they are successfully challenged.

For example, in the early 2000s, after realizing that foreign firms had dominated the market for 2G wireless telephony devices, the governments of both Korea and China sought to assist their domestic industries in the area of 3G standardization. Korea supported Qualcomm’s CDMA One wireless telecommunications technology in exchange for presumably favorable terms for Korean vendors. China, in contrast, embarked on a go-it-alone approach to 3G standardization, producing a competing TD-SCDMA technology that was not heavily patented by Western interests.Footnote 27 Neither of these approaches proved to be successful, and the telecommunications markets in both Korea and China have now gravitated toward international interoperability standards, with Korean and Chinese firms playing significant roles in international SSOs.Footnote 28

Another protectionist approach is the targeted enforcement of existing regulations against foreign entities. There has been a spate of recent competition law investigations and enforcement actions against large Western holders of standards-essential patents in China, Korea and India.Footnote 29 For example, in February 2015, China’s National Development and Reform Commission (henceforth “NDRC”) fined Qualcomm approximately US$975 million for a host of alleged violations of China’s Antimonopoly Law in connection with its licensing of standards-essential patents. The Korean Fair Trade Commission is also reported to be investigating Qualcomm. In India, the Competition Commission of India (henceforth “CCI”) has investigated Ericsson in connection with Ericsson’s patent infringement suits against Indian and Chinese manufacturers of mobile phones for the domestic Indian market.Footnote 30

A final way that governments can seek to reduce the dominance of foreign patent holders in domestic markets is through the imposition of compulsory licensing for particular patents or products. This power, which is permitted under TRIPS in special circumstances, has to-date been exercised primarily in pharmaceutical markets in developing economies. Nevertheless, the possibility of compulsory licensing exists in other industries that have a significant impact on health, safety and welfare of local populations.Footnote 31 In response to the dominance of the local Indian mobile devices market by foreign patent holders, some have proposed the imposition of a compulsory licensing regime in this market.Footnote 32

6.3 Increase Patenting by Local Firms

As the competitive advantage possessed by Have firms derives to a large degree from patents on standardized technology, some have suggested that it would benefit local firms to increase their own patenting activity.Footnote 33 Increased patenting by local firms would, it is argued, give such firms greater bargaining power in licensing negotiations with existing Have firms. While this conclusion is correct on a theoretical level, it may oversimplify the issue. The acquisition of patents is not itself a productive activity, but a by-product of technological innovation. Thus, unless one seeks to encourage speculative patenting divorced from technical development (a goal that most would agree is undesirable), obtaining patents must be coupled with technological development. To the extent that patents cover technical standards, that technical development usually occurs in connection with participation in an SSO.Footnote 34 Thus, to enhance their bargaining position Have-Not firms should seek not to increase their patenting activity, but their participation in international standardization activities.Footnote 35 If they do, their ability to obtain patents covering their technical contributions should follow.

It is, of course, a separate matter whether local governments should facilitate patenting by domestic providers. Doing so in a manner that discriminates against foreign firms would generally run afoul of TRIPS and other treaty obligations.Footnote 36 However, governments can help their domestic industry by funding additional R&D and SSO participation.

6.4 Benefits of Increased SSO Participation by Local Firms

The potential benefits that Have-Not firms can derive from increased participation in international SSOs are numerous. First, SSO participants can influence the direction of standardized technologies in a manner that favors, or at least takes into consideration, local markets or local technology/patent positions. Involvement in charting the future direction of technology standards can also give firms insight into and advance notice of product development and evolution opportunities. Participation may also offer local firms opportunities to export interoperable products beyond the domestic market. It may also afford increased opportunities for patenting in domestic markets and abroad, and will inform foreign firms of the technology and patent assets that local firms have available for licensing.

From a policy standpoint, increased involvement in SSOs would give Have-Not firms opportunities to influence SSO policies and practices, particularly in ways that might facilitate licensing and technology dissemination in developing markets. For example, SSO policies could provide that offering lower royalty rates for deployment of standards-compliant products in developing markets would not violate the SSO’s requirement of non-discriminatory treatment.Footnote 37 Likewise, SSOs could mandate reduced-royalty or royalty-free licensing in certain markets or under certain conditions.

6.5 Incentivizing Increased SSO Participation

Despite these potential advantages, with a few exceptions, Have-Not firms have not yet made meaningful and sustained contributions to major international SSOs. This absence is rendered more notable by express policies intended to ensure broad participation in such SSOs. For example, participation in international Category I SSOs such as ISO and ITU is often determined on a national basis.Footnote 38 The national delegations to bodies such as these present good opportunities for involvement by firms from less-developed countries. Some Category I SSOs such as ETSI, and most Category II SSOs, such as IEEE, ASTM and IETF are, by their own policies, open to participation by all interested organizations. Accordingly, the only barriers to participation in these SSOs, which represent a significant portion of global standardization activity,Footnote 39 arise from a lack of technical skill, financial resources and interest among Have-Not firms. These deficiencies are, of course, very real and very serious. However, they can be overcome, at least in part, through national and philanthropic programs that provide resources for technical training and participation in international SSOs.Footnote 40 The example of Chinese firms such as Huawei and ZTE,Footnote 41 illustrate that it is possible for local firms, with sufficient determination, governmental support and expenditure of resources, to become significant forces in international standardization activities.Footnote 42

Trade agreements, despite their potential to facilitate the involvement of local firms in international SSOs, have, to date, done little in this regard. Though the recent Trans-Pacific Partnership agreement (TPP) includes an entire chapter devoted to standards, its goal is ensuring that locally-developed standards, generally those relating to health and safety, are open and transparent and do not discriminate against foreign producers.Footnote 43 The standards focus of the TPP is thus inward looking with respect to less-developed countries, ensuring that they allow international firms to enter without standards-based barriers, rather than outbound, or helping them to participate in the broader global standardization community.

In addition, future trade agreements could encourage greater openness to Have-Not participation in nationally-based SSOs, require that nationally-adopted standards originate from open SSOs, and establish international bodies designed to support Have-Not participation in international SSOs.

More important than trade agreements, however, may be international and local capacity building efforts to support greater international SSO participation by representatives from Have-Not firms. Such support could come in the form of grants from local governments, non-governmental organizations (henceforth “NGOs”),Footnote 44 and multi-governmental organizations [e.g., the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)]. SSOs themselves could also offer financial support to Have-Not firms wishing to participate, underwritten by the membership dues paid by their existing multinational firm members. With such support programs in place, the steep costs of international SSO participation could be defrayed for Have-Not firms, thus broadening overall participation and promoting broader representation in these critical global organizations.

A final component of this governmental and institutional support for standardization is educational. Countries such as India already possess world-class educational institutions in the science and engineering disciplines. However, it is not clear that these institutions uniformly emphasize standards education and training. The need for greater education in the area of standards has been noted even within the United States by the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST), which has funded efforts at several U.S. universities to promote curriculum and program development relating to standards, and itself offers various training programs relating to standards for U.S. government agencies and the private sector.Footnote 45

6.6 Applications in India

The types of support mechanisms described in Part 6.5 above may seem superfluous in jurisdictions such as India, which are already major markets for ICT products and possess a sophisticated governmental and private sector organizational infrastructure devoted to standardization. For example, the Indian government’s Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) conducts standardization activity in fourteen industry sectors including computer communications, networks and interfaces.Footnote 46 The Telecommunications Engineering Center (TEC) operated by the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, coordinates with international SSOs including ETSI, ITU, IEEE and IETF in developing telecommunications standards.Footnote 47 Private trade associations such as the Telecom Standards Development Society of India (TSDSI), the Global ICT Standardization Forum for India (GISFI), and the Development Organization of Standards for Telecommunications in India (DOSTI) facilitate the development of standards for the Indian ICT sector, often in cooperation with international SSOs.Footnote 48

But it may be the very existence of this domestic standardization infrastructure that inhibits greater direct Indian participation in international SSOs. The seemingly sophisticated network of Indian standardization activities may have made the Indian government and industry somewhat complacent about participation in leading international standardization efforts. But these activities are by no means equivalent in importance or impact. While domestic standardization efforts may facilitate the adoption and adaptation of international standards for local Indian needs (admittedly, a necessary function), they appear largely to follow the lead of the dominant international SSOs, rather than participate in their leadership. Participation in domestic standardization activities is thus no substitute for active engagement at the international SSO level. Thus, it seems that the Indian government and private standards groups could increase their prominence internationally by supporting (institutionally and financially) greater engagement by Indian firms in international SSOs.

7 Conclusion

Patents on standardized technologies are being issued with increasing frequency, and the majority of these patents are held by large multinational firms based in developed economies. As a result, firms from less-developed economies with sparse patent holdings are disadvantaged in both domestic and foreign markets. While protectionist governmental policies can address these disparities, such measures are potentially contrary to international treaty obligations and generally unsuccessful in the long term. An alternative approach involves greater participation in international SSOs by firms from less-developed economies. This increased participation is likely to benefit such firms both in terms of technology development, strengthening of patent positions, and influence over SSO policies. To facilitate increased participation, both financial and institutional support will be required from local governments, NGOs, multinational organizations and SSOs themselves. However, if participation in international SSOs by firms in countries such as India can be increased, it could have a meaningful impact on domestic innovation, job creation, technical capability and manufacturing output.

Notes

- 1.

Dieter Ernst, America’s Voluntary Standards System – A Best Practice Model for Innovation Policy?, East-West Center Working Paper No. 128, (2012); Brad Biddle, et al., The Expanding Role and Importance of Standards in the Information and Communications Technology Industry, 52 Jurimetrics 177 (2012).

- 2.

Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Circular A-119 (1998).

- 3.

European Comm’n – Directorate-General for Enterprise and Indus. (EC). 2014. Patents and Standards: A Modern Framework for IPR-Based Standardization.

- 4.

The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) presents a somewhat unusual case, in as much as it is a private organization which is recognized in certain capacities by the U.S. government. ANSI oversees, accredits and establishes policy for national SSOs that wish to develop American National Standards. Among other things, ANSI-accredited SSOs must adopt due process and intellectual property policies that comply with ANSI’s “Essential Requirements”.

- 5.

Updegrove catalogs more than 1,000 such groups. Andrew Updegrove, “Standard Setting Organizations and Standards List” CONSORTIUM INFO. (2015), http://www.consortiuminfo.org/links/#.VarhPnjDRD0.

- 6.

Justus Baron & Daniel F. Spulber. Technology Standards and Standard Setting Organizations: Introduction to the Searle Center Database (2015), http://www.law.northwestern.edu/research-faculty/searlecenter/innovationeconomics/documents/Baron_Spulber_Searle%20Center_Database.pdf.

- 7.

Dieter Ernst, Indigenous Innovation And Globalization: The Challenge For China’s Standardization Strategy (2011); Jorge L. Contreras, Divergent Patterns of Engagement in Internet Standardization: Japan, Korea and China, 38 Telecomunications Pol’y. 914-932 (2014).

- 8.

Brad Biddle, et al., The Expanding Role and Importance of Standards in the Information and Communications Technology Industry, 52 Jurimetrics 177 (2012).

- 9.

A patent “family” consists of all individual patents deriving from a single, initial patent application. These may include individual patents in multiple countries, as well as multiple patents in the same country derived from the same initial application (e.g., continuations, continuations-in-part and divisionals in the U.S.). See Knut Blind et al., Study on the Interplay between Standards and Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs), Final Report (2011), http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/european-standards/files/standards_policy/ipr-workshop/ipr_study_final_report_en.pdf.

- 10.

Carl Shapiro & Hal R. Varian, Information Rules: A Strategic Guide To The Network Economy (1999).

- 11.

Jorge L. Contreras, Technical Standards, Standards-Setting Organizations and Intellectual Property: A Survey of the Literature (With an Emphasis on Empirical Approaches), in RESEARCH HANDBOOK ON THE ECONOMICS OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW, VOL. II - ANALYTICAL METHODS (Peter S. Menell & David Schwartz, eds., Edward Elgar: 2017, forthcoming).

- 12.

Mark A. Lemley & Carl Shapiro, Patent Holdup and Royalty Stacking, 85 TEX. L. REV. 1991-2049 (2007); Jorge L. Contreras, Patents, Technical Standards and Standard-Setting Organizations: A Survey of the Empirical, Legal and Economics Literature, in Research Handbook On The Economics Of Intellectual Property Law, Vol. II – Analytical Methods (Peter S. Menell & David Schwartz, eds., 2017, forthcoming).

- 13.

FRAND commitments (or similar commitments to license patents on a royalty-free basis) are required of all SDOs accredited by ANSI.

- 14.

Jorge L. Contreras, Fixing FRAND: A Pseudo-Pool Approach to Standards-Based Patent Licensing, 79 Antitrust L.J. 47-97 (2013).

- 15.

Rudi Bekkers & Joel West, The limits to IPR Standardization Policies as evidenced by Strategic Patenting in UMTS, 33 Telecom. Pol. 80-97 (2009).

- 16.

Blind et al., supra note 9; Justus Baron & Tim Pohlmann, Mapping Standards to Patents using Databases of Declared Standard-Essential Patents and Systems of Technological Classification (2015), http://www.law.northwestern.edu/research-faculty/searlecenter/innovationeconomics/documents/Baron_Pohlmann_Mapping_Standards.pdf.

- 17.

Contreras, supra note 7.

- 18.

Though Japanese firms such as Sony, Toshiba, Sharp and Panasonic have played major roles in many areas of ICT standardization, particularly consumer electronics and digital media, they are comparatively underrepresented in telecommunications and networking SSOs, due largely to early policies adopted by the Japanese government. See Contreras, supra note 9.

- 19.

U.S. Patent & Trademark Office. 2015. All Technologies (Utility Patents) Report, http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/ac/ido/oeip/taf/all_tech.htm#PartB.

- 20.

Jorge L. Contreras & Rohini Lakshané, Patents and Mobile Devices in India: An Empirical Survey, 50 Vanderbilt Transnat’l. L.J. 1-44 (2016).

- 21.

Contreras, supra note 7.

- 22.

In addition, the royalty burden on local Have-Not firms is often greater than the burden on other foreign Have firms that hold patents that may be used as bargaining chips in cross-licenses with other Have firms. The result is that Have firms that have entered into cross-licensing networks generally have a low monetary royalty burden as compared to Have-Not firms that lack patents essential to relevant standards.

- 23.

Dieter Ernst, Indigenous Innovation And Globalization: The Challenge For China’s Standardization Strategy (2011).

- 24.

Dept. Industrial Policy & Promotion (DIPP), Indian Ministry of Commerce & Industry, Discussion Paper on Standard Essential Patents and their Availability on FRAND Terms, Mar. 1, 2016; Contreras & Lakshané, supra note 20; Dieter Ernst, Global Strategic Patenting and Innovation – Policy and Research Implications, East-West Center Working Papers: Innovation and Economic Growth Series, No. 2 (2015), http://www.eastwestcenter.org/system/tdf/private/iegwp002.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=34977.

- 25.

World Trade Organization, Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization, Annex 1C, 15 April 1994, in World Trade Organization, The Legal Texts: The Results of The Uruguay Round of Multilateral Trade Negotiations 321 (1999), available at http://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/27-trips.pdf.

- 26.

Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Chapter 8 (Technical Barriers to Trade).

- 27.

ERNST, supra note 7.

- 28.

Contreras, supra note 7.

- 29.

To some degree, these investigations echo similar investigations by U.S. and European competition law authorities.

- 30.

DIPP, supra note 24; Contreras & Lakshané, supra note 20.

- 31.

Jorge L. Contreras & Charles R. McManis, Compulsory Licensing of Intellectual Property: A Viable Policy Lever for Promoting Access to Critical Technologies?, in TRIPS AND DEVELOPING COUNTRIES – TOWARDS A NEW IP WORLD ORDER? (Gustavo Ghidini, et al., eds., 2014).

- 32.

Rohini Lakshané, Letter to Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modi, Mar. 24, 2015, http://cis-india.org/a2k/blogs/open-letter-to-prime-minister-modi.

- 33.

Florian Ramel & Knut Blind, The Influence of Standard Essential Patents on Trade, (paper presented at IEEE-SIIT Conference, Sunnyvale, California, Oct. 6, 2015).

- 34.

While individual firms often develop technologies internally which they then bring to SSOs for standardization, a significant amount of revision, compromise and development also occurs within the collaborative SSO setting.

- 35.

See, infra section 6.4.

- 36.

These obligations require local patent offices to afford “national treatment” to foreign applicants, treating them on the same basis as local applicants.

- 37.

Major research universities around the world have adopted a similar stance in a 2007 document entitled “In the Public Interest: Nine Points to Consider in Licensing University Technology”. The “Nine Points” document expressly acknowledges that “responsible licensing includes consideration of the needs of people in developing countries and members of other underserved populations”.

- 38.

See, supra section 2.

- 39.

Because Category 3 SSOs (consortia) are typically formed by small groups of firms with an existing technology and patent position, it is not realistic to hope that they will be fruitful avenues for greater Have-Not firm participation.

- 40.

For example, the Internet Society, a US/Switzerland-based NGO, regularly sponsors a number of Fellows from developing countries to participate in meetings and other activities of the IETF. http://www.internetsociety.org/what-we-do/education-and-leadership-programmes/ietf-and-ois-programmes/internet-society-fellowship.

- 41.

Contreras, supra note 7.

- 42.

Of course, China underwent a phase during which it concentrated significant resources on the development of local standards without heavy foreign patent coverage (see supra section 6.2) discussing initiatives such as China’s TD-SCDMA 3G mobile telephony effort, as well as Ernst (2011), which details several such efforts). While many would argue that these efforts were ultimately of limited success, it is possible that they did serve the unexpected purpose of preparing Chinese firms to participate in international standardization efforts.

- 43.

See Trans-Pacific Partnership, Chapter 8 (Technical Barriers to Trade).

- 44.

For example, the IETF fellows program sponsored by the Internet Society (see supra note 40).

- 45.

See www.nist.gov.

- 46.

DIPP, supra note 24.

- 47.

Id.

- 48.

Id.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Contreras, J.L. (2018). National Disparities and Standards Essential Patents: Considerations for India. In: Bharadwaj, A., Devaiah, V., Gupta, I. (eds) Complications and Quandaries in the ICT Sector. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6011-3_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-6011-3_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-10-6010-6

Online ISBN: 978-981-10-6011-3

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)