Abstract

The report observes that – with context-driven caveats – the Romanian Constitution could be categorised as representing ‘legal’ or post-authoritarian constitutionalism. The report outlines weaknesses in Romanian constitutionalism, including issues that have necessitated the EU post-accession monitoring procedure. At the same time, it also documents a number of ways in which EU law has caused strain on the constitutional culture. In particular, it emerges that many of the key adverse impacts of EU law explored in the present research project were raised by Romanian courts. For example, the Romanian Constitutional Court was the first to annul the national law implementing the EU Data Retention Directive, and a lower instance court was the first, in Radu, to send a question about the presumption of innocence and liberty in the context of the automaticity of extraditions in the European Arrest Warrant system to the ECJ. The constitutional adjudication by the Constitutional Court is marked by a high proportion of annulments, especially on substantive grounds. The report also outlines the adjudication regarding the European Commission and IMF austerity programmes, social rights and the economic emergency regime. Regarding the discourse, the report makes insightful observations about the way the constitutional language and logic are changing through EU and transnational law, e.g. as regards the adaptation of the proportionality analysis from protecting the individual to benefitting commercial freedom. The report observes that the older methodological predilection for ‘simplistic legal positivism with a thin Marxist sauce’ (Czarnota) has been replaced by an equally simplistic and often instrumental internationalisation.

The author is Associate Professor (Comparative Constitutional Law and Constitutional Theory), University of Bucharest, Faculty of Political Science. e-mail: Bogdan.Iancu@fspub.unibuc.ro.

All websites accessed 5 October 2015. Text submitted 9 October 2015 with minor changes added on 7 February 2017.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- The Constitution of Romania

- Constitutional amendments regarding EU and international co-operation

- The Romanian Constitutional Court

- Constitutional review statistics and grounds

- Fundamental rights and the rule of law

- European Arrest Warrant

- Radu, presumption of innocence and liberty

- Data Retention Directive and surveillance

- Supremacy

- Changing language of constitutionalism at the transnational level

- Limitation of rights

- The principle of proportionality and Omega, Laval and Viking Line

- IMF and European Commission austerity and conditionality programmes, social rights and economic emergency

- Parliamentary reservation of law

- Anti-corruption as a form of quasi-constitutional discourse

- International arbitration treaties and public protests

1 Constitutional Amendments Regarding EU Membership

1.1 Constitutional Culture

1.1.1 The current Constitution of Romania was adopted in 1991, two years after the collapse of state socialism, and was extensively revised in 2003, in prospect of the country’s impending NATO membership (2004) and EU accession (2007).

Due to the fact that pre-totalitarian constitutional traditions were (correctly) perceived as fused at the hip with the monarchical form of government and since restoration of the monarchy was not a feasible option in the early 1990s, the post-communist fundamental law bears little resemblance (e.g. in terms of institutional framework) to the pre-WWII liberal-democratic experiences of the country under the Constitutions of 1866 and 1923.Footnote 1

Even though some general institutional choices were predicated by the Constitutional Committee upon the rationale of tradition and continuity,Footnote 2 for example the bicameral option and the names of the houses of Parliament (Chamber of Deputies and Senate), the actual composition and functioning of the two houses do not correspond to earlier Romanian parliamentary practices. In other crucial aspects, the break with the past is more apparent still: for instance, the 1990/1991 constituent assembly opted for a constitutional court, instead of reviving the early twentieth century tradition of judicial review by all the courts of general jurisdiction or by the High Court of Cassation and Justice.Footnote 3

Consequently, most provisions of the current fundamental law are adapted foreign transplants (for instance, semi-presidentialism). Many norm aggregations simply reflect the results of open-ended, post-communist ‘bricolage’.Footnote 4 Rights and liberties were copied verbatim but somewhat haphazardly from various Western bills of rights and international documents, whereas some institutional choices were transplanted wholesale, without a clear idea of whether and how they would fit into the overall structure. In the case of the Ombudsman, for example, the office was provided for by the 1991 Constitution but was not established by an organic law until 1997; due to the lack of effective powers, the ‘Advocate of the People’ remained until very recently a purely decorative institution.

A boilerplate remark concerns alleged affinities between the French model and Romanian constitutional practice.Footnote 5 On closer inspection, one can notice few functional similarities between the French Fifth Republic and the Romanian system. For instance, although a few of the President’s powers were initially inspired by the design of the French Constitution, Romanian semi-presidentialism is a much weaker form of its French institutional counterpart.Footnote 6

With context-driven caveats regarding legal culture, one could categorise the Romanian Constitution under ‘legal’, post-authoritarian rather than ‘evolutionary’ constitutionalism (according to Besselink’s taxonomy as per the Questionnaire).

1.1.2

In the logic of the initial, pre-2003 version of the Constitution, the accent or centre of gravity fell on sovereignty and the organisation of the state. The Constitution opens (compare and contrast, for instance, with the structure of the German Basic Law) with an article on ‘The Romanian State’, described in the first paragraph as ‘a sovereign, independent, unitary and indivisible National State’, followed by provisions on ‘Sovereignty’ (Art. 2), ‘Territory’ (Art. 3), and ‘Unity of the People and Equality among Citizens’ (Art. 4). The first paragraph of the ‘eternity clause’ (Art. 152, ‘Limits of Revision’) shields the ‘national, independent, unitary and indivisible character of the Romanian State’ from subsequent amendments.

By the same token, the initial version of the fundamental law provided for a relatively weak Constitutional Court (its findings of unconstitutionality could be overridden by Parliament, by a two-thirds supermajority) and judiciary.

The 2003 amendments and constitutional practice have to a certain extent shifted the focus towards checks and balances, by way of entrenching the autonomy of certain key institutions from the political branches. For instance, by virtue of these amendments, the Constitutional Court, the Superior Council of the Magistracy and the Ombudsman acquired more prominent roles within the system. The position of the Superior Council of the Magistracy (SCM) as ‘guarantor of judicial independence’ (Art. 133(1)) was virtually insulated from all kinds of overt democratic-majoritarian control by way of appointments. Moreover, the institution was entrusted with all decisions concerning the career of ‘magistrates’ (i.e. both prosecutors and judges). Likewise, in the case of the Constitutional Court, the parliamentary override was eliminated, additional attributions were introduced (e.g. ruling on ‘conflicts of a constitutional nature between public authorities’, Art. 146(e)) and procedural remedies were added (e.g. the Ombudsman can trigger concrete review by way of an exception of unconstitutionality raised directly before the Court, Art. 146(d)). Nonetheless, this realignment – in the context of an unsettled constitutional system and culture – is not necessarily devoid of ambiguities and tensions of its own. Although the changes can in principle and generally be categorised as conducive to the rule of law, checks and balances and fundamental rights, one has to take this description with a contextual grain of salt.Footnote 7

1.2 The Amendment of the Constitution in Relation to the European Union

1.2.1

In view of the expected accession to the EU in January 2007, the Constitution was amended by Law No. 429/2003 on the revision of the Constitution.

Title VI, ‘Euro-Atlantic Integration’, consisting of Arts. 148 (Integration into the European Union) and 149 (Accession to the North Atlantic Treaty) was included in the text in 2003, interspersed between the titles on the Constitutional Court and Constitutional Revision, respectively.

Article 148 reads as follows:

- (1)

Romania’s accession to the constituent treaties of the European Union, with a view to transferring certain powers to community institutions, as well as to exercising in common with the other member states the abilities stipulated in such treaties, shall be carried out by means of a law adopted in the joint sitting of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, with a majority of two thirds of the number of deputies and senators.

- (2)

As a result of the accession, the provisions of the constituent treaties of the European Union, as well as the other mandatory community regulations shall take precedence over the opposite provisions of the national laws, in compliance with the provisions of the accession act.

- (3)

The provisions of paragraphs (1) and (2) shall also apply accordingly for the accession to the acts revising the constituent treaties of the European Union.

- (4)

The Parliament, the President of Romania, the Government, and the judicial authority shall guarantee that the obligations resulting from the accession act and the provisions of paragraph (2) are implemented.

- (5)

The Government shall send to the two Chambers of the Parliament the draft mandatory acts before they are submitted to the European Union institutions for approval.Footnote 8

Other amendments have concerned electoral rights and the acquisition of property. Article 16(4) protects the right of European citizens ‘who comply with the requirements of the organic law’ to elect and be elected ‘to the local public administration bodies’ (i.e. mayors and local or county council positions).Footnote 9

Article 38 provides for the right (N.B!) of Romanian citizens to be elected to the European Parliament: ‘After Romania’s accession to the European Union, Romanian citizens shall have the right to elect and be elected to the European Parliament.’

Article 44(2) provides that ‘[f]oreign citizens and stateless persons shall only acquire the right to private property of land under the terms resulting from Romania’s accession to the European Union and other international treaties Romania is a party to, on a mutual basis, under the terms stipulated by an organic law, as well as a result of lawful inheritance’.

Only supremacy is mentioned in the text, which does not mean that direct effect is not recognised.Footnote 10 It has also been noted in the doctrine that, whereas the article requires the same supermajority for the parliamentary adoption of ratification legislation (of both the accession treaty and subsequent revisions of the constitutive treaties) as that mandated for constitutional amendments, the two procedures differ markedly. In the case of the ratification of EU treaties, the majority is computed on the basis of the total number of deputies and senators convened in a joint session of Parliament, whereas in the case of amendments, a two-thirds supermajority must be obtained in each house. If this is not achieved and the conference committee procedure fails, a three-fourths majority in joint session is needed to adopt the amendment law.Footnote 11

1.2.2 The Constitution can be revised (subject to observing the limits of revision, according to Art. 152) by adopting an amendment law. The right of initiative belongs to the President on the proposal of the Government, one-fourth of the deputies or senators, or 500,000 citizens, provided that 20,000 signatures in support of the amendment are collected from at least one-half of the counties (including the Municipality of Bucharest) (Art. 150).

The bill has to be passed by each house with a two-thirds majority or by a three-fourths majority in joint session, should the conference committee procedure fail to build a consensus on a common draft of the bill. Once adopted, the revision law is submitted to a referendum, which must be organised within 30 days (Art. 151). The Constitutional Court decides on the constitutionality of revision initiatives (Art. 146(a) and Arts. 19–23 of Law No. 47/1992 regarding the organisation and functioning of the Constitutional Court) within ten days, upon receipt of the draft bill accompanied by the opinion of the Legislative Council, before the initiative is laid before Parliament. A finding of unconstitutionality must be supported by a two-thirds majority of the Court, i.e. at least six justices (Art. 21(1), Law 47/1992). The Court also decides ex officio on the revision law, within five days of its adoption. The competence of the Court includes the verification of both procedural forms and substantive elements concerning the limits of revision (‘extrinsic’ and ‘intrinsic’ constitutionality). In the case of a finding of unconstitutionality, the law is sent back to Parliament for reconsideration.

Amendments must be approved by referendum. In the case of the ‘EU amendments’ of 2003, massive absenteeism could have hampered the entire process, which would have been stalled by an eventual invalidation of the referendum. The 50% participation quorum was only met due to a last-minute extension of the poll to two days.

In 2013, the Referendum Law was amended and the quorum was reduced to a 30% participation rate and 25% validly cast ballots, numbers to be computed on the basis of the permanent electoral lists. Hypothetically, a constitutional revision could be approved by 12,5% of the registered voters. These changes have been applicable since 2014, one year after the publication of the 2013 amendments to the Referendum Law, according to a decision of the Constitutional Court that upheld the amendments but postponed the application of this new rule by one year.Footnote 12

1.2.3 Article 148 and the provisions regarding rights were perceived in 2003 as sufficient legal bases for accession and integration.

Joint constitutional drafting committees of Parliament routinely co-opt legal scholars and experts, both at the stage of stakeholder and ‘civil society’ consultations, prior to committee debates (‘Constitutional Forums’) and at the drafting stage. The extent to which societal or academic advice is taken into consideration depends on political vagaries and imponderables, as does the selection process of academic committee memberships. Such consultative procedures are often window-dressing.

For instance, a 2008 presidential expert committee on constitutional revision co-opted academics (experts in political science and public law), charged with discussing the flaws of the constitutional system and proposing amendments. When a considerable number of the initial membership resigned, some of them making accusations of pressures to conform, the ‘defectors’ were quickly replaced and the committee’s work continued unabated. In the end, the incumbent President selected the recommendation that suited his institutional preferences and worldview predilections from the report. The writer of this report was appointed to a consultative academic committee attached to the parliamentary drafting committee, in the course of a recent (2013) parliamentary revision initiative. The comments initially made by the academics on drafts and minutes forwarded by the joint parliamentary committee were disregarded and, after a couple of weeks, the MPs broke communication and simply ignored the consultative expert body.

1.2.4

An amendment proposal initiated by the Presidency in 2011 sought to make marginal changes to Art. 148, introducing a new paragraph according to which the ratification of the accession of a new state to the Union would be ‘made by a law adopted by Parliament, with the majority of two-thirds of its members’. Another proposed change was the elimination of a paragraph in Art. 44, regarding ‘the presumption of lawful acquisition of property’, in a context where this clause was seen as impeding the fight against corruption and in particular the transposition of Framework Decision 2005/212/JHAFootnote 13 on extended confiscation (see infra, Sect. 1.3.3). This project eventually got bogged down in the legislature, due to the lack of a clear supporting majority, more pressing agenda issues and, eventually, the change of government in early 2012.

The 2013 parliamentary revision proposal, initiated by the governing coalition, included some amendments related to EU membership. One of the proposed alterations was declaratory if not superfluous, concerning an additional paragraph in Art. 10 (International relations): ‘Romania is a Member State of the European Union.’

Another modification concerned the form of the second paragraph of Art. 148, which after amendment would have read: ‘Romania shall guarantee the application of EU law in the internal legal order, in accordance with the Act of Accession and other treaties concluded within the Union’ (emphasis added).

The revision also sought to ‘clarify’, to the detriment of the President, the constitutional deadlock concerning the country’s representation in European Council meetings. Article 91, which concerns presidential attributions in the field of foreign affairs, would have comprised an additional paragraph, reading as follows: ‘The President shall represent Romania in (sic!) European Union meetings and conferences (reuniunile Uniunii Europene) concerning foreign relations, the common security policy and the revision of the constitutive treaties.’ Conversely, the proposal would have introduced a new paragraph to Art. 102 (Role and Structure of the Government), which read: ‘The Government shall represent the country at all EU meetings, with the exception of those mentioned in Art. 91(1).’ These two proposals were rejected by the Constitutional Court. In the case of the former, the argument of the Court rested on constitutional supremacy. The reasoning is relevant to this volume and worth quoting at some length:

To establish a rule according to which EU law would apply without any qualification in the internal legal order, without distinguishing between the Constitution and subordinate legislation equates the subordination of [Romanian] constitutional law to the legal order of the EU. From this perspective, the Court notes that the fundamental law of the state – the Constitution – is an expression of popular will and cannot forfeit its binding force as a result of contradictory EU law. Accession to the Union does not affect the supremacy of the Constitution over the entire internal legal order.Footnote 14

In the matter of European Council participation, the Court held in essence that the proposed changes, due to both faulty drafting and neglect of precedent, would have further confused the constitutional powers of the President and Prime Minister and fostered constitutional deadlocks.Footnote 15

The revision law was not adopted, due to the numerous invalidations and recommendations to reformulate it made by the Court; furthermore, the government coalition was meanwhile dismantled, resulting in the absence of a parliamentary majority able to carry the vote.

1.3 Conceptualising Sovereignty and the Limits to the Transfer of Powers

1.3.1 Supremacy of EU law is mentioned expressly in the Constitution, whereas direct effect is accepted by the Constitutional Court in practice as implied.Footnote 16 Problems arose and a protracted constitutional battle ensued with respect to representation in the European Council (see e.g. above Sect. 1.2.4).

1.3.2 In its first decision touching on the transfer of sovereign powers to the EU (the decision concerning the constitutionality of the 2003 amendment law), the Constitutional Court stated:

Member States have decided to exercise certain functions in common that traditionally pertained to the purview of national sovereignty. It is undeniable that in our age of globalised human concerns, intensified inter-state interactions and worldwide means of communication among individuals, the concept of sovereignty cannot be conceived as absolute and indivisible without incurring the unacceptable risk of international isolation.Footnote 17

1.3.3

Article 152, regarding the limits of revision, rests on the premise of a core of unalterable constitutionality and could, at least in principle, form the basis for the emergence of a constitutional jurisprudence that would put the brakes on integration (just as the constitutional core established by the eternity clause of the German Basic Law has led to the jurisprudence regarding ‘identity control’, Verfassungsidentität). This supposition is however an academic exercise. As things stand at the moment, the Constitutional Court has taken a consistently ‘EU-friendly’ stance in terms of the actual results, albeit not necessarily in the evolution of its argumentation (see Sect. 1.2.4).

Further, legislation transposing the Data Retention DirectiveFootnote 18 has twice been declared unconstitutional. In neither case was a preliminary reference sought; the first decision assailed the failure of the lawmaker to avail itself of the transposition leeway, whereas the second ruling followed the lead of the European Court of Justice (see Sect. 2.4).

A proposal to modify the Constitution in order to eliminate the ‘presumption of lawful acquisition of property’ from the text of Art. 44 (right of private property) was declared unconstitutional, although the Court hastened to add that nothing prevented the lawmaker from transposing the Justice and Home Affairs acquis (in particular the Framework Decision 2005/212/JHA on confiscation of crime proceeds, instrumentalities and property) at the level of ordinary legislation.Footnote 19

1.3.4 As in the case of other Eastern European systems,Footnote 20 some early post-accession decisions evidenced a degree of unfamiliarity with the new jurisdictional setting. For instance, in a decision on an exception of unconstitutionality concerning a challenge to a state aid granted to small and medium-sized enterprises in the beer industry, the Court interpreted the direct effect of Arts. 87–89 EC Treaty and held that the principle of direct effect implied the use of different interpretive methods in domestic constitutional adjudication.Footnote 21

Obversely, once the principles of ‘cooperative federalism’ were internalised, the balance shifted to a sort of categorical positivistic stance, according to which conflicts of competence and jurisdiction could not arise, since the two legal orders were clearly separated.

1.4 Democratic Control

1.4.1 The constitutional amendment regarding parliamentary participation (Art. 148(5)) was mentioned in Sect. 1.2. There are standing Committees on European Affairs in both the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. Members of these committees are appointed by the houses, upon nomination by the parliamentary factions, negotiated according to the proportional breakdown of the parties’ parliamentary representation. The two bodies have symmetrical powers concerning the national legislative process (committee debates of draft legislation transposing EU directives) and EU lawmaking (reporting opinions concerning the application of the Subsidiarity Protocol back to the houses). In addition to their legislative functions, both committees hold advice and consent hearings regarding national appointments to EU institutions and the nomination of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and hold inquiries into the exercise of the country’s mandate and vote in the Council.Footnote 22

Law No. 373/2013 regarding the Relations between Parliament and the Government in the Field of European AffairsFootnote 23 regulates the procedure for exercising the national parliamentary prerogatives according to the second protocol to the Treaty of Lisbon, as well as the supervision of harmonisation, and the right of Parliament to be informed with regard to all appointments to EU institutions and to hold appointment hearings with respect to European Commissioner nominations.

1.4.2 Even though the 2003 revision did not exclusively concern the EU and NATO-related amendments (Title VII, Arts. 148–149 and the rights provisions), the revision was primarily presented to the citizenry as a prerequisite to European integration and was perceived as being focused on and linked with EU accession.

In the end, participation reached the 50% validity threshold only as a result of the extension of the poll by emergency ordinance, from one to two days. Out of the 55.7% of registered voters who did eventually turn out, 89.7% voted in favour of the amendments. This discrepancy between the lack of interest in going to the poll and quasi-unanimous approval of the revision (constitutionalism without a constitutional moment, as one might say) can be explained as a result or consequence of the top-down, hasty nature of the pre-accession negotiations and of an instrumental perception of integration. Accession as such, the desideratum of ‘returning to Europe’ was widely supported, yet people perceived themselves as having little voice and choice in the scope and pace of integration.

1.5 The Reasons for, and the Role of, EU Amendments

1.5.1 Even though it contains few clauses that are directly related to the EU, the Constitution has been considerably overhauled due to EU accession, albeit in less apparent ways.

For example, as a result of the pre-accession monitoring along the Copenhagen Criteria, the Superior Council of the Magistracy (SCM) was insulated in 2003 from almost any kind of meaningful political (democratic majoritarian) or social form of influence. The transplantation or rather importation of a version of the French-Italian high judicial council model, proffered by international bodies as a ‘best practice’ of judicial organisation,Footnote 24 was a direct consequence of pre-accession recommendations of the European Commission, coupled with a readily available ‘Ikea [institutional] model’Footnote 25. This understanding of judicial independence, which in the Romanian context encompasses, under the institutional umbrella of the SCM, both judges and prosecutors, has produced significant ripple effects in the functioning of the Romanian political-constitutional system. Likewise, the EU-induced, quasi-constitutional feature of anti-corruption policies and entrenched institutions has considerably influenced the actual functioning of the Romanian constitutional system. Moreover, Romania, together with Bulgaria, is under post-accession monitoring within the framework of the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism (CVM). The European Commission reporting in the framework of the CVM started in 2012 to include a section on the constitutional system. Commission delegations have liaised more recently with the Constitutional Court. Furthermore, one can observe increasing cross-hybridisation and cross-citation between the European Commission and the Venice Commission in recent years.

All these factors, even though they cannot be subsumed under positive constitutional law (black letter law EU-clauses), have a significant impact on the context and operation of the domestic system. These changes will be further discussed below in Sects. 2.3.6 and 2.13.

1.5.2 Although the amendments are relatively numerous, some were poorly formulated. The limitations are to a certain extent due to a lack of foresight. For instance, in the matter of representation in the European Council, the constitutional conflict between the President and the Prime Minister could have been anticipated, given the bifurcated nature of the executive branch, a notorious characteristic of semi-presidential systems. The issue, like many other gaps in the fundamental law of Romania, was partly clarified by an interpretive gloss by the Constitutional Court. A narrow and contested 2012 rulingFootnote 26 attributed the competence to the President, based on the rationale that the office of ‘the head of state’ was constitutionally entrusted with preeminent attributions in the field of foreign affairs. According to this holding, the Prime Minister can only take part in European Council meetings in the President’s stead, on the basis of an explicit delegation by the latter.

However, a subsequent majority decision muddled the 2012 ruling, by holding that the President has only a fettered discretion in the matter and, according to ‘the principle of loyal cooperation among state institutions’, he must take into account, in deciding whether to delegate this competence to the Prime Minister,

certain objective criteria, such as i. the institution best placed in what concerns the topics on the agenda of a European Council meeting; ii. Whether the position of the President or the Prime-Minister is validated by a congruent standpoint of the Parliament; iii. the difficulties related to the implementation of European Council decisions.Footnote 27

1.5.3 The perception of the role of national constitutions vis-à-vis internationalisation is highly charged with normative presuppositions about the limits and scope of national constitutions, and indeed about the proper limits of delegation to international bodies. To wit, a Habermasian sees the state as a transitional instrument and would find little common ground on this matter with an advocate of purely administrative-regulatory supranational or international integration as coordination.Footnote 28 An inextricably linked question is whether traditional constitutional principles, norms and institutions can be translated outside their original environment, in order to offset and compensate displacements of decisional competence beyond the nation state.

In my view, national constitutions remain for now the primary locus of legitimacy and the main point of democratic decisional ascription. Hence, their role is, at least for the foreseeable future and at least as the primary legitimacy transmission belts, secure. This is not to deny the considerable pressures put on national constitutions by integration, especially in the crisis context of the current acceleration of EU-related developments.

Constitutions and their safe-keepers, constitutional courts, with their focus on normativity and the ends of political community, also serve (or at least have the potential to serve) the important function of censoring and disciplining the supranational institutions, by constantly restating the normative questions about the kind of European constitutionalism that is feasible at any given juncture. According to Dieter Grimm, constitutional courts are even ‘the only institutions that in the current configuration constitute a counterweight [Gegengewicht] to the democracy-averse mechanisms [demokratie-mindernden Mechanismen] which are at work within the EU’ [emphasis added].Footnote 29

2 Constitutional Rights, the Rule of Law and EU Law

2.1 The Position of Constitutional Rights and the Rule of Law in the Constitution

2.1.1 Fundamental rights are codified in the Constitution. Title II (fundamental rights and freedoms) comprises a relatively long list of rights and liberties, without a clear analytical delineation according to subject-matter, so that social and economic rights defined as state duties to protect (Art. 35, right to a healthy environment) are interspersed between classical civil and political rights. Title III lists duties, namely faithfulness towards the country, the duty to defend the country, financial contributions and the prohibition of abuse of rights. Proportionality is defined in the text of the Constitution (Art. 53(2)).

The rule of law, human dignity and the free development of personality are protected as general constitutional principles; Art. 1(3) defines them as ‘supreme values’.

2.1.2 Article 53 (restriction on the exercise of certain rights and freedoms) reads:

- (1)

The exercise of certain rights or freedoms may only be restricted by law, and only if necessary, as the case may be, for: the defence of national security, of public order, health, or morals, of the citizens’ rights and freedoms; conducting a criminal investigation; preventing the consequences of a natural calamity, disaster, or an extremely severe catastrophe.

- (2)

Such restriction shall only be ordered if necessary in a democratic society. The measure shall be proportional to the situation having caused it, applied without discrimination, and without infringing on the existence of such right or freedom.

The principle of proportionality is methodologically understood as comprising the familiar steps (provided by law, legitimate objective, necessity and proportionality in the narrower sense (balancing)).

2.1.3

The rule of law (‘statul de drept’) is mentioned as a ‘supreme value’ (Art. 1(3)). Article 1(5) defines the principle of legality: ‘the observance of the Constitution and its supremacy and of the laws is mandatory’ (the two provisions are often interpreted in conjunction).

The term ‘stat de drept’ (neologism of French inspiration, État de droit) is sometimes used in the literature in conjunction or even interchangeably with the notion ‘domnia legii’ (the rule of law, in an ad litteram translation). However, the latter concept means (in its Romanian conceptual context) only legality, subordination of the state to the law.

The concept of ‘stat de drept’ is understood in the doctrine as encompassing not merely the supremacy of the Constitution and the principle of legality of administration but also qualitative-substantive criteria, such as stability and certainty, predictability, the duty to give reasons (not only for judicial decisions but also for administrative action) and proportionality.Footnote 30

The principle of the rule of law has been invoked as an argument in constitutional review. In Romania, there are two types of cases of constitutional review by the Constitutional Court: ‘objections of constitutionality’, which denote ex ante abstract review, and ‘exceptions of unconstitutionality’, which mean ex post concrete review.Footnote 31 The rule of law is invoked in both types of cases.

However, the Constitutional Court refrained until relatively recently from encouraging or even lending credence to its use as a justiciable principle; it intimated that the rule of law was too grand a concept to have practical justiciable bite. For example, in rejecting an exception of unconstitutionality to a law ratifying a government ordinance concerning foreign currency transactions, the Court noted:

In what concerns the degree to which the impugned norm fulfils the exigencies of the rule of law principle … the Court notes that the said principle defines the major objectives of state activity, as envisioned by what is customarily called the supremacy or rule of law (domnia legii), which means subordination of the state to legality, the existence of structures that allow law to censor political options, and within this framework enable the law to ponder the abusive or discretionary tendencies of state institutions. The rule of law guarantees the supremacy of the Constitution, the constitutionality of inferior legal norms, and the separation of powers, which are only to act within the bounds of law and more particularly within the limits of a law expressing the general will [emphasis added].Footnote 32

The rule of law has been used sparsely by the Court, for instance as a complementary argument for affirming the erga omnes character of Constitutional Court decisions solving exceptions of unconstitutionality, namely the effect of constitutional decisions on the adjudication by referring courts of general jurisdiction.Footnote 33

However, more recently, the Constitutional Court has given more clout to rule of law guarantees, perhaps also as a result of institutional interaction and socialisation with international structures, such as the EU Commission and the Venice Commission in whose institutional discourses the rule of law concept looms large. The rule of law (and the principle of legality, Art. 1, Paras. (3) and (5)) was used as an argument to strike down, in its entirety, a 2015 legislative proposal which, ostensibly in anticipation of the draft EU Network and Information Security (NIS) Directive,Footnote 34 would have entrusted all policy and regulatory decisions in the field of informational security to the Romanian Intelligence Service. The NIS directive, proposed by the European Commission in 2013, has not yet been adopted and thus cannot be transposed. Therefore, this argument was an attempt to make a controversial domestic policy more palatable for a national audience, by reference to a presumptively respectable and unquestionable EU ‘standard’. No access to a court was provided in the bill. The Court declared the law unconstitutional on grounds of a breach of privacy rights, access to justice and due process, and legality (clarity, precision and predictability of the norm). It cited its decision 70/2000, adding this time that the principle of the rule of law is not purely procedural but also presupposes ‘a series of guarantees, including jurisdictional safeguards, to ensure the protection of rights and liberties by means of limiting the state’.Footnote 35

In the field of anti-corruption legislation, the rule of law argument was used by the Court to strike down a proposed amendment to the Criminal Code, which sought to shield appointed or elected officials from prosecution for misfeasance or abuse of office and corruption crimes by restricting the definition of ‘public servant’ to low-level civil servants. The Court reasoned that such an amendment would have hampered the fulfilment of international commitments (anti-corruption treaties ratified by the country prior to EU accession), the stability of state institutions and, by implication, the trust of the citizens in state institutions.Footnote 36

2.2 The Balancing of Fundamental Rights and Economic Freedoms in EU Law

2.2.1 The balancing of fundamental rights with economic free movement rights has not raised constitutional issues in Romania so far, due to the relatively idiosyncratic economic circumstances of the country.

2.3 Constitutional Rights, the European Arrest Warrant and EU Criminal Law

2.3.1 The Presumption of Innocence

2.3.1.1 The Constitutional Court has thus far rejected all exceptions of unconstitutionality regarding the transposition law, Law No. 302/2004.Footnote 37 It has stressed that the internal surrendering procedure meets all constitutional requirements and that all due process guarantees will be surely respected in the Member State requesting the extradition. The position of the Constitutional Court is that the executing court has no authority to rule on the merits of the measure taken by the judicial authority requesting the surrender. According to the Court, ‘[c]hallenges regarding the merits will be made in the Member State from which the warrant was issued, where all [fair trial] guarantees will be observed’.Footnote 38

The Court of Appeal of Constanța made a preliminary reference to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) questioning the way in which the presumption of innocence might be infringed in the case of an automatic surrender for the purposes of prosecution, where the surrendered person has not previously been heard by the issuing judicial authorities.Footnote 39 The referring court asked whether deprivation of liberty and forcible surrender under a European Arrest Warrant (EAW), without the consent of the person, constitutes interference with the right to individual liberty on the part of the state executing the warrant, and whether such a forced surrender satisfies the requirements of necessity in a democratic society and of proportionality in relation to the objective actually pursued. The reference was based on Arts. 6, 48 and 52 of the EU Charter and Arts. 5 and 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Constitutional rights were not mentioned in the preliminary reference. The question whether constitutional rights could be considered by the referring court, on the basis of Art. 20 in the Constitution, upon determining whether international law or the Constitution or national laws comprise more favourable provisions is fraught with jurisdictional and procedural difficulties. Conflicting views persist with respect to the question whether ordinary courts can rely on Art. 20 and consider autonomously which provisions (national or international) provide a more favourable treatment to a fundamental right; the prevailing opinion is that problems of constitutionality are a monopoly of the Constitutional CourtFootnote 40 (see also Sect. 3.2.2). Thus, the referring court motivated the request for a preliminary reference exclusively on the basis of fundamental rights guarantees deriving from EU law (the Charter and general principles of EU law, which include the ECHR).Footnote 41

The Grand Chamber of the CJEU found that Framework Decision 2002/584Footnote 42 must be interpreted as meaning that the executing judicial authorities cannot refuse to execute a European Arrest Warrant issued for the purposes of conducting a criminal prosecution on the ground that the requested person was not heard in the issuing Member State before the arrest warrant was issued.

2.3.1.2 Preliminary review is granted by the courts of appeal; these are the courts which, according to the transposition law, are charged with deciding in first instance on the execution of European Arrest Warrants.

Whilst no statistical studies are available, examples of refusal to execute an EAW, grounded in breaches of fair trial guarantees, can be found in the practice of the appeal courts.Footnote 43

2.3.2 Nullum crimen, nulla poena sine lege

2.3.2.1 The principle of legality of incrimination is guaranteed by Art. 23(12) of the Constitution, according to which ‘[p]enalties shall be established or applied only in accordance with and on the grounds of the law’. According to the Constitutional Court, this provision entails the premise that the primary lawmaker, by parliamentary statute, or the delegated legislator (i.e. the Government, by means of an ordinance or an emergency ordinance) must legislate with clarity and not simply incorporate by reference and analogy subordinate normative instruments or administrative interpretations in the definition of a criminal offence.Footnote 44

Problems arose in the matter due to conflicting interpretations and the ensuing jurisdictional turf wars between the Constitutional Court and the High Court of Cassation and Justice. For instance, when a 2007 Constitutional Court decision declared the decriminalisation of libel and slander unconstitutional on the grounds of a breach of dignity, conflicting interpretations arose in practice. Some courts held that the consequence of the decision was the ‘abrogation of the abrogation’ and consequent re-criminalisation, whereas some courts deemed the decision inconsequential until such time as the lawmaker should decide to heed it and recriminalise defamation. Conflicting decisions by the Constitutional Court (2013, exception of unconstitutionality) and the High Court of Cassation and Justice (2010, recurs în interesul legii (extraordinary appeal on points of law)), with neither jurisdiction yielding to the other’s interpretation, did little to clarify this legal quagmire.Footnote 45

A more recent clash occurred in the context of the entry into force of the New Criminal Code, with divergent decisions over the interpretation of the lex mitior principle and its application to the so-called autonomous criminal law institutions (such as repeat offences, plurality of offences, statutes of limitations).Footnote 46 The High Court considered that, during the overlap, judges could combine provisions concerning the crimes and ‘autonomous institutions’ rules, in order to compute the sanctioning regime most favourable to the offender, whereas the Constitutional Court interpreted penal retroactivity to mean choosing the most favourable regime to the defendant, as established by either of the two codes taken as a whole.

The overall complexity entailed by the interpretation of the principle of legality of incrimination is not yet reflected in, and no jurisdictional conflicts have as of yet arisen with regard to, the interpretation of the EAW transposition law, due to the institutional reservations to deal with the matter of judicial cooperation. The Constitutional Court invariably rejects all exceptions of unconstitutionality concerning Law No. 302/2004; the High Court routinely orders the execution of warrants on appeal.

2.3.3 Fair Trial and In Absentia Judgments

2.3.3.1 The right to a fair trial is guaranteed under Art. 21 of the Constitution. Paragraph 3 reads: ‘All parties shall be entitled to a fair trial and a solution of their cases within a reasonable term.’ According to Art. 24, throughout the trial parties have the right to be represented by a court-appointed defender or a private lawyer. The general fair trial guarantee also implies ECHR standards since, the Romanian Constitution adopts a ‘monist-comparative’ solution with respect to human rights treaties, which means that the higher level of protection, domestic or international as the case may be, will be applied (Art. 20).

The Constitutional Court has interpreted Art. 21 to imply the principle of equality of arms in criminal law. For instance, a very recent decision declared unconstitutional an article of the new Criminal Procedure Code which authorised the rendering of rulings on granting revision relief (an extraordinary appeal) with the participation of the prosecutor but without citing the parties.Footnote 47 According to the new Criminal Procedure Code that entered into force on 1 January 2014 (Art. 466), a criminal trial can be reopened if the initial judgment resulted from an in absentia procedure. In absentia is defined as justified impossibility to take part in the proceedings and inability to notify the court of the matter or lack of citation or official notice. The term for introducing such action is relatively stringent, i.e. a month from the date of having knowledge of the conviction.

The European Court of Human Rights has ruled against Romania (violation of Art. 5) in a case involving the reopening of an in absentia trial, pursuant to surrender on the basis of an EAW. The former criminal procedure code did not provide for the possibility of the court to suspend the execution of the initial sentence after reopening the proceedings.Footnote 48

2.3.4 The Right to a Fair Trial – Practical Challenges Regarding a Trial Abroad

2.3.4.1 Neither public nor private funding is available for covering the legal expenses of individuals surrendered pursuant to an EAW.

The rate of acquittal is well under the European average. Recurrent public debates have revolved around the somewhat higher percentage of acquittals in anticorruption cases (as compared with ‘regular’ criminal law trials), which, according to statistics and annual official releases of the National Anticorruption Directorate, levels around 9% yearly.Footnote 49

2.3.4.2 No official data or statistics of any kind exist regarding extradited individuals who have subsequently been found innocent.

2.3.5 The Right to Effective Judicial Protection: The Principle of Mutual Recognition in EU Criminal Law and Abolition of the Exequatur in Civil and Commercial Matters

2.3.5.1 Not applicable.

2.3.5.2 Debates on the suitability of transposing mutual recognition from (ostensibly less problematic) internal market and regulatory matters to criminal law and civil and commercial disputes presuppose an internalisation of legal debates that have gradually, incrementally grappled with the legislative and judicial developments in ‘old Europe’, in slow lockstep with the evolution of practices.

Romania is a recent Member State where enthusiasm for accession was not yet been blunted by qualifications and reservations regarding the proper course of integration. By the same token, Romanian legal doctrine is still characterised by a strong positivistic penchant (and a relatively rudimentary strain of positivism). The ‘mechanical jurisprudence’Footnote 50 and doctrine entailed by this post-communist methodological propensity are not very useful in the context of sophisticated new practices, such as the emerging European ‘constitutionalisation’.

2.3.5.3 Concerns about the shift in the role of the judiciary have thus far not been adequately addressed, whereas the dearth of commentary on these issues is a ground for concern. More generally, few writings exist on the impact of Europeanisation on judicial culture.Footnote 51

In the case of the younger generation of judges and scholars, the older methodological predilection for ‘simplistic legal positivism with a thin Marxist sauce’Footnote 52 has been replaced by or seasoned with an equally unselfconscious, simplistic and often instrumental internationalisation. That is to say that international documents, case law, developments, soft law and doctrine are cited in an often encomiastic and rather haphazard manner, without clear distinctions or an analytically disciplined assimilation (‘internalisation’) of the developments and practices concerned.

In the case of the judiciary as such, the openness towards dialogical incursions and international networking are coupled with an increasing isolation from all internal accountability mechanisms: in the name of judicial independence, the Superior Council of the Magistracy has been virtually isolated from all social or political levers of responsibility and, moreover, this original transposition of the French-Italian model has subsequently been progressively shielded by the Constitutional Court from future amendments (see Sects. 1.1.2 and 2.3.6).Footnote 53 A recent decision of the Constitutional Court rendered even a recall procedure, by virtue of which the Superior Council was accountable to the system as such, inoperative.Footnote 54

2.3.5.4 In the context of an increased use of EAW execution requests and the trivial matters at stake in some requests, the introduction of a proportionality test would be welcome.

2.3.6 EU Monitoring of Anticorruption Measures in Romania

Romanian criminal law and penal policy have been significantly influenced by pre- and post-accession conditionalities relating to anticorruption measures. One could safely say that anticorruption criminal policy functions almost as a quasi-constitutional phenomenon, insofar as it significantly affects both the operation of the political-constitutional systems as such, and patterns of institutional discourses and structures of justification.

The focus on anti-corruption as a determining criterion in the monitoring of the new Member States is a more general recent tendency of the UnionFootnote 55 which may by virtue of a ratchet effect generate new EU constitutional vocabularies and institutional developments.Footnote 56 To wit, the Vice-President of the European Commission at the time, Justice Commissioner Viviane Reding, recently floated the idea of a post-accession new constitutional mechanism, analogous to the Copenhagen criteria. The Justice Commissioner supported her plan to solve the ‘Copenhagen dilemma’ (i.e. the non-democratic derailment of a Member State after accession) by reference to the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism for Romania and Bulgaria.Footnote 57 The proposal of squaring the circle between soft power and the ‘nuclear option’ of Art. 7 TEU (in Reding’s words) by way of a ‘post-Accession Copenhagen’ is now under consideration in the European Commission and European Parliament. Whether or not it will be explicitly called so in the constitutive treaties, a European constitutional area (which includes quasi-constitutional vocabularies such as anti-corruption) has crystallised at the interface of national and international guarantees.

The post-accession CVM mechanism was initially scheduled to lapse after three years (in 2010) but has in the meanwhile been extended, seemingly indefinitely. The judicial reform and the related anti-corruption benchmarks have taken the upper hand in the monitoring. In the aftermath of a protracted domestic constitutional crisis in 2012, the European Commission has included general references to the ‘Romanian constitutional system’ as such in its biannual reports. This was supported with/based on the argument that judicial reform is related to the rule of law and, although not technically a part of the judicial system, the Constitutional Court and the Constitution are essential to the rule of law.

More concretely, anti-corruption policies are implemented in the field of penal policy by the National Anticorruption Directorate (NAD), a structure ostensibly subordinate to the General Prosecutor’s Office Attached to the High Court of Cassation and Justice (in the vernacular, it is still referred to by its former title, the General Prosecutor’s Office of Romania). NAD has jurisdiction over mid- and high-level corruption, defined ratione materiae by the value of the bribe or prejudice that has to exceed 10,000 and 200,000 EUR, respectively. Ratione personae, the institution has jurisdiction over corruption crimes committed by enumerated categories of public officials, according to Law 78/2000 on the Prevention, Investigation and Sanctioning of Corrupt Acts. In practice, the office is fully autonomous, since the symmetrical modes of appointment and tenures of both the General Prosecutor and the Chief Prosecutor of the NAD in practice guarantee the functional independence of the anti-corruption prosecutorial office within the Public Ministry.Footnote 58

A wave of high-profile arrests and convictions have nearly captured the public sphere. There are neatly divided camps, on the one hand of detractors of anti-corruption prosecutions, which are perceived as politically motivated and/or a form of ‘televised justice’ and, on the other hand, supporters, who see anti-corruption policies and institutions as a panacea or – in the extreme version of the discourse – even a substitute for a corrupt political system.Footnote 59 The very autonomy of the structure, which is monitored effectively only by the High Council (itself a fully autonomous body), lends itself easily to speculative journalism about the ends and means of anti-corruption.

2.4 The EU Data Retention Directive

2.4.1 The Romanian Constitutional Court was first confronted with national legislation implementing the Data Retention Directive in 2009, prior to the annulment of the Directive by the Court of Justice.

The Romanian Constitutional Court ruled on an exception of unconstitutionality regarding Law No. 298/2008 and held that the open-ended authorisation to collect traffic data and ‘related data (date conexe)’ was a disproportionate infringement of the constitutional guarantees of the freedom of expression, the right to secrecy of correspondence and the general right to privacy.Footnote 60 Proportionality played a crucial role in the analysis, since Art. 53 on restriction of certain rights and liberties is the reference norm for assessing rights limitations.

The Court emphasised the way in which blanket retention of data affected the rights of the addressees of electronic or mobile phone communications: ‘[t]he rights to privacy of the addressee of a communication are thus exposed in the absence of any element of volition, as a result of someone else’s behaviour, without having the possibility to counter the latter’s bad faith or intention to harass or blackmail the addressee.’Footnote 61 The Court also stressed the way in which blanket retention has a chilling effect on rights and inevitably creates a general climate of suspicion.

A new transposition law, Law 82/2012, brought before the Court by an exception of unconstitutionality, was struck down in July 2014 (the law was invalidated in toto).Footnote 62 Law 82/2012 had purported to heed the prior constitutional ruling by making marginal or cosmetic changes to the impugned provisions (so that, for instance, ‘related data [date conexe] needed for the identification of the subscriber or user’ became, simply, ‘necessary data’). The Court noted that such amendments were not of a nature to alter its position, insofar as the provisions continued to be open-ended and the law did not seek to limit the number of individuals and officials with access to such data to the greatest degree possible.

In its reasoning, a unanimous Court stressed that:

[T]he infringement of fundamental rights regarding private and family life, secrecy of correspondence, and freedom of expression is very wide in its scope and reach [de mare amploare] and must be considered extremely serious [deosebit de gravă], whereas the fact that such data are subsequently stored and used without informing the subscriber or registered user is of the nature to imprint in the consciousness of concerned individuals the feeling that their private lives are subject to constant surveillance [emphasis in original].Footnote 63

Interestingly, the 2014 ruling considered that implementation of the Directive concerns two stages, namely, blanket storage of data and use of the stored information, respectively. Only unsupervised access to data was deemed constitutionally suspect, insofar as privacy and secrecy of correspondence are concerned. According to the Court,

[T]he Court appreciates that the nature and specificities of the first stage, insofar as the lawmaker deems the storage necessary, does not in and of itself impinge upon the exercise of the right to private and family life or the secrecy of correspondence. Neither the Constitution nor Court precedents forbid preventive retention and storage, inasmuch as use of the data is accompanied by adequate safeguards and is not disproportionate in nature.Footnote 64

The structure of the reasoning, in this respect, tracks that of the annulment judgment of the CJEU.

A significant part of the 2014 ruling grappled with a peculiarity of recent Romanian legislation, i.e. the large scope of delegations to the intelligence services. Thus, the 2014 decision invalidated an authorisation to the intelligence services, which, according to the law, would have received a generous access to traffic data ‘concerning the prevention and combatting of threats to national security’. This mandate, the justices observed, unlike the request of a prosecutor (which must be sanctioned by the judge of rights and liberties), was not controlled by a court or indeed by any external body.

Moreover, whereas two national institutions, the Data Protection Agency (Autoritatea Națională de Supraveghere a Prelucrării Datelor cu Caracter Personal (ANSPDCP)) and a regulatory agency (Autoritatea Națională pentru Administrare și Reglementare în Comunicații (ANCOM)) are nominally entrusted with the supervision of the way in which public service providers fulfil their legal obligations with respect to data retention, storage and access, and can impose sanctions (misdemeanour fines), the Court noted that ‘no authentic control mechanism exists, to ensure that such institutions permanently and effectively implement the law [i.e. in monitoring the public services providers]’.Footnote 65

In September 2014, a majority decision declared unconstitutional legislative provisions which introduced an obligation, incumbent upon service providers, to retain and store identification data pertaining to purchasers of prepaid SIM cards and users of open access internet services. The reasoning departs from the logic of the earlier ruling in July, insofar as in the paradigm of the newer decision blanket retention and storage as such (‘first stage’) are described as negatively affecting constitutional rights.Footnote 66 This volte face in argumentation was duly pointed out and criticised by the three dissenting justices.

In early 2015, a unanimous Court rendered a decision on a germane issue, declaring the Law on ‘Cybersecurity’ unconstitutional in its entirety. The impugned act would have in effect granted broad, almost unfettered supervisory discretion over data and internet network security policy to the Romanian Intelligence Service (SRI). The ‘Cybersecurity Law’ purported to ‘transpose’ avant la lettre the draft NIS Directive (see supra Sect. 2.1.3).Footnote 67

In early 2015, in the wake of this series of decisions of unconstitutionality concerning the legislation transposing the Data Retention Directive, the retention of identification data pertaining to purchasers of prepaid SIM cards, and the Law on ‘Cybersecurity’, the President of the Constitutional Court publicly accused the SRI of exerting undue pressure on the justices (i.e. to render constitutionality rulings). In response, the incumbent Director of the Romanian Intelligence Service, George Maior, charged the Court for its alleged lack of moral responsibility and good faith and subsequently resigned, arguing that the unconstitutionality decisions had crippled the pursuit of his institution’s objectives and mission and consequently the fulfilment of his own mandate as Director of internal intelligence.Footnote 68

In October 2015, another data retention law (also dubbed the ‘Big Brother Law’) was passed in Parliament. Law 235/2015 Amending Law 506/2004 On Personal Data Processing and the Protection of Privacy in the Field of Electronic CommunicationsFootnote 69 explicitly provides that all requests for traffic data, ‘made by prosecutors or state authorities with national defence or intelligence attributions’, have to be authorised by a judge; traffic, location or equipment identification data must be deleted or anonymised within three years at most. When a request from a court or prosecutor’s office or state authority with defence or intelligence attributions is made for such data, the obligation of service providers to store and preserve such data extends to a maximum term of five years from the date of the request or the date of the rendering of a final court judgment, respectively. This last ‘Big Brother’ law was prepared by extended consultations among party factions, under the patronage of the Presidency, and consequently passed by a landslide in Parliament. Thus, it was not challenged before promulgation, and the Ombudsman raised no direct exception of unconstitutionality before the Court. Nonetheless, the lack of an ‘abstract’ challenge leaves still open a possible ‘concrete’ challenge by exception of unconstitutionality raised by a party in the course of a future criminal trial, should the evidence issue from application of this law.

2.5 Unpublished or Secret Legislation

2.5.1 Unpublished or secret measures would not pass the constitutional muster, insofar as they were normative in nature. In this respect, the curbing of Romanian Intelligence Service attributions by virtue of the ‘Cybersecurity Decision’ of 2015 is apposite. The reluctance of the Constitutional Court to sanction the incorporation by reference of administrative acts (e.g. ministerial orders and circulars) is also relevant in this vein.

2.6 Rights and General Principles of Law in the Context of Market Regulation: Property Rights, Legal Certainty, Non-retroactivity and Proportionality

2.6.1 Not applicable.

2.7 The ESM Treaty, Austerity Programmes and the Democratic, Rule-of-Law-Based State

2.7.1 Not applicable.

2.7.2 Not applicable.

2.7.3

Romania was subject to EU-related Balance-of-Payments (BoP) ‘economic emergency’ measures right after the onset of the sovereign debt crisis.Footnote 70 In 2009, the Council agreed to make medium-term financial assistance of up to 5 billion EUR available, in conjunction with a Stand-by Agreement with the IMF (in the amount of 11.4 billion SDR, approximately 12.9 billion EUR), with a further 2 billion EUR being provided by the World Bank (WB), the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) (the WB provided 1 billion under a Development Policy Loan, whereas the EBRD and the EIB provided 1 billion combined).

The measures agreed with the lenders did not single out pension or salary cuts (see, for instance, the Memorandum of Understanding with the European Commission of 23 June 2009, which recommended only foregoing scheduled salary increases and replacing departing public employees at a rate of 1 to 7).Footnote 71 Yet the agreed budgetary and fiscal discipline targets were such that few alternatives to salary and pension cuts were available.

Law 329/2009Footnote 72 was passed in furtherance of obligations undertaken by Romania through memoranda concluded with the European Commission and the IMF. It provided for a restructuring of public institutions (entailing also, under certain conditions, the firing of redundant public service employees), the rationalisation of public expenditures by 15.5% monthly reductions in October-December 2009, and the obligation of public employees drawing a pension higher than the average gross salary to opt between the pension and the salary.

The Constitutional Court was seized of the issue in abstract review, by virtue of an objection of unconstitutionality raised by the parliamentary minority. The objection identified various procedural and substantive flaws. In terms of procedural flaws, the complainants argued that the plea of necessity under Art. 53, under which the law had been adopted, did not conform to the constitutional conditions regarding the declaration and imposition of a state of emergency. This argument was important, since a national state of emergency on the ground of ‘defence of national security’ constitutes a legitimate purpose for restriction of rights according to Art. 53, which provides for the proportionality principle. According to the argument of the complainants, since the law was justified as an emergency measure, the requirements of Government Emergency Ordinance 1/1999 on the state of siege and the state of emergency should have been applied. Moreover, the parliamentary challenge was based on the reasoning that, according to Art. 93 (on emergency powers), the President should have instituted a state of siege or state of emergency and asked for parliamentary approval within five days at the latest. The Constitutional Court dismissed this objection to the austerity measures adopted under a plea of necessity, with the reasoning that the term ‘defence of national security’, as used in Art. 53, has a wider meaning than the term ‘state of siege or state of emergency’ envisioned by Art. 93. What is worthy of note is that the Court thus confirmed that restriction of rights in the context of an economic crisis qualifies as part of ‘defence of national security’ under Art. 53.

A second procedural argument was less dramatic in nature. The complainants alleged that the law unlawfully presumed (in the case of restructuring) that a positive clearance would in fact be issued by the audit authority, the Court of Accounts.Footnote 73

The complainants additionally put forth a number of substantive objections, arguing that the law infringed the right to property (Art. 44) and the right to ‘labour and social protection of labour’ (Art. 41), insofar as it compelled publicly employed pensioners to opt between the two incomes. Further, the general prohibition of discrimination in Art. 16 was also invoked with regard to the firing criteria.

The law was upheld by a majority of the Court, except insofar as it covered ‘constitutionally entrenched offices and mandates’ (an interesting and perhaps not fully public-spirited exception). The majority opinion insisted upon the proportionality and especially the time limitation of most restrictions:

We must emphasise that the essence of the constitutional legitimacy of rights or liberties restrictions is the exceptional and temporary character of a measure. … It falls upon the state to find solutions to counteract the economic crisis, by adequate economic and social policies. The reduction of public sector employees’ incomes cannot constitute, in the long term, a proportional measure. Contrariwise, the extension of such measure may result in unintended effects and disturb the good functioning of public institutions and state authorities.Footnote 74

There were three dissenting justices, who emphasised that the complainants were correct to raise the procedural argument regarding the requirement for the Court of Accounts to authorise cases of institutional reorganisation by means of government decree (Hotărâre de Guvern). Additionally, they stressed the substantively distinct levels of constitutional protection which ought to apply to pensions and public sector salaries, respectively. This minority caveat resurfaced in subsequent majority opinions.

A series of constitutional decisions (Nos. 872, 873, 874) was rendered by the Constitutional Court on 25 June 2010 on conditionality-related austerity measures. The most prominent ruling was Decision 872/2010,Footnote 75 which resulted from an objection of unconstitutionality raised (referred) by the High Court of Cassation and Justice.Footnote 76 Law 118/2010 on Measures Necessary to Restore Budgetary Balance welded together a string of restrictions, among which were the reduction of pensions by 15%, a 25% public sector salary cut and a 15% diminution of unemployment benefits and child allowances. According to the High Court, the reductions were disproportionate and discriminatory, the reiteration of the restrictions in 2010 breached the principle according to which restrictions ought to be temporary in order to be considered proportionate, and was also – insofar as the cuts were applicable to the judicial system – in breach of judicial independence.

Most of the challenges were held by the Constitutional Court to be unfounded, either in proportionality review (salaries) or in principle. In the case of the argument regarding judicial independence, the Court insisted that judges ought to shoulder common burdens and that judicial independence comprises many elements, ‘none of which must be either neglected or absolutised’. Some challenges were rejected by the Court with the procedural reasoning that not all social benefits are protected constitutionally to begin with, and thus can be either granted or stripped at the legislative level.

However, the Constitutional Court upheld the challenge of unconstitutionality referring to the scheduled pension cut, with the argument that constitutional protection in Art. 47(2) and the special character of pensions, which are partly contributory in nature, shielded them from state interference. The state could not invoke hardship in defence of such measures, as the good husbandry of the social insurance budget is incumbent on the state. According to the Court,

[T]he aim of the pension is to compensate during the passive life of the insured person the latter’s contribution to the State social security budget under the contributory principle and to ensure the means of subsistence of those who have acquired this right by law (contributory period, retirement age, etc.). Thus, the State has a positive obligation to take all means necessary to achieve that objective and to refrain from all conduct likely to limit the right to social security.

In terms of reasoning, although the tenor of the argument of the High Court in its referral was that pension would be a form of property under the Constitution and the ECHR, and although the Constitutional Court did cite in support of its own reasoning the well-known decisions of the Hungarian Constitutional Court from 1995 and 1997, the decision did not rest upon the argument that some parts of the social insurance scheme would be accorded ‘property-like protection’.Footnote 77 Article 44 (right to property) was not mentioned in the court’s reasoning. The finding of unconstitutionality with respect to pension reductions rested entirely on Art. 47(2) (living standard), which refers to the right to pensions in the same vein as the right to maternity leave, public health care, unemployment benefits ‘and other forms of public or private social securities’, generically referred to as ‘the right to social assistance, according to the law’.

Another referral from the High Court, adjudicated on the same day, concerned the 2010 Law Concerning some Measures with Respect to Pensions. The act sought, in the crisis context, to subject the so-called ‘special pensions’ (i.e. pensions of Members of Parliament, members of the military and diplomatic services, the judiciary, prison system, police, etc.) to the general legislative regime applicable to the contributory pension scheme. Whereas the austerity measures were generally upheld on the basis of the argument that such pensions were not calculated on the basis of the ‘contributory principle’ and were thus not constitutionally immune from changes, the rule seeking to eliminate the service pension of judges, prosecutors and ‘assistant magistrates’ of the Constitutional CourtFootnote 78 was struck down. This seems somewhat paradoxical in the light of the Court’s previous ruling; the reasoning of the Court was that it would have infringed upon the principle of judicial independence and prosecutorial impartiality, as guaranteed by Arts. 124(3) and 132(1) of the Constitution.Footnote 79

In another decision rendered on the same date, Decision 874/2010,Footnote 80 the Constitutional Court adjudicated on a further objection regarding the Law on Measures Necessary to Restore the Budgetary Balance, raised by deputies and senators. The objection revisited in part the analytical structure of the High Court referral, previously addressed by Decision 872 (regarding the constitutional definition of emergency, the nature of acquired rights, the special status of pensions, etc.). An additional and somewhat eccentric argument in the MPs’ objection was that the salary cuts not only breached legitimate expectations but also imposed a levy on the public sector, analogous to a tax burden. The logic was that, should the cut be considered a form of taxation, this would lead to the conclusion that the general prohibition of discrimination in Art. 16 and the requirements contained in Art. 56(2) (fair distribution of the tax burden) were also breached, since private sector employees would contribute 16% of their revenue to the state budget whereas their counterparts in the public sector would suffer a burden of 41% of their income. Since the issues mirrored in good part those addressed in its prior decision, the Constitutional Court reiterated and refined the main tenets of its prior reasoning. First, emergency has an autonomous meaning in Art. 53. Here, the Court renewed its extensive references to IMF and EU Commission reports in order to substantiate the existence of an economic emergency. Secondly, all forms of social protection mentioned in the Constitution can be restricted if proportionality is observed. And thirdly, the right to a pension has a special status, which implies legitimate expectations that are opposable to the state and immunises this right from arbitrary governmental intrusions. Again, the Court refused to explain the special constitutional character of pensions by exclusive reference to contributiveness, i.e. in terms of a property-oriented justification. It held the pension cut to be unconstitutional solely by reference to Art. 47. Had the argument been formulated in terms of property, the extension of the unconstitutionality finding to the reduction of allowances paid for the attendants of disabled pensioners would have been difficult to justify, as such pensions and attendant allowances are based on need.Footnote 81

The logic of the Court strikes therefore a mild ‘Solomonic’ chord in this respect, since the exclusive reliance on the ‘living standard’ guarantee of Art. 47 fails somewhat to explain the complete denial of protection to other rights enumerated in that article and affected by the austerity measures (maternity, unemployment benefits, etc.). Arguably, another Solomonic inconsistency of the austerity-related case law of the Constitutional Court is the use of the principle of judicial independence to single out and immunise the special pensions of magistrates from reduction (but not their salaries).

2.8 Judicial Review of EU Measures: Access to Justice and the Standard of Review

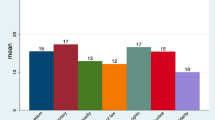

2.8.1 Romanian courts (with the exception of the Constitutional Court, which has made no request for a preliminary ruling as of yet) have been increasingly active in making referrals to the CJEU. To date, 104 requests for a preliminary ruling have been made, originating from all jurisdictional tiers (Judecătorii, Tribunale, Curți de Apel, Înalta Curte de Casație și Justiție).Footnote 82 Out of these referrals, 29 are still pending and 75 have been finalised. Out of the latter, 32 resulted in preliminary rulings, 17 were rejected as inadmissible, another 17 were disposed of by reasoned order on the basis of Art. 99 of the Rules of Procedure and 9 were removed from the docket at the request of the referring court.

One can notice a steady increase in references over the last few years. Over half of the requests for preliminary references (57) have been registered with the Court of Justice during the past three years alone (the breakdown is: 12 since 1 January 2015, 38 in 2014, 17 in 2013, 13 in 2012, 14 in 2011 and 17 in 2010).

The subject matter of the cases runs almost the full gamut of prerogatives of the Union, e.g. from rights attached to European citizenship to the interpretation of the non-discrimination directive and the free movement of goods.