Abstract

The Portuguese Constitution of 1976 shares some of the main features of the constitutions adopted after the fall of an authoritarian regime, such as detailed rules and enforceability in court. The constitutional culture is mostly influenced by continental constitutional traditions, especially the French constitutional experience as regards the organisation of the state, and Germany in relation to the rule of law and fundamental rights. Rights from the first to the fourth generation are protected in some sixty articles, with detailed sub-clauses, and with a particularly strong social solidarity dimension and social rights. In the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court, measures have often been annulled on the grounds of violation of the principles of equality, proportionality and the protection of legitimate expectations. This approach was enhanced in relation to the drastic austerity measures resulting from the European Union and IMF bailout programmes. The so-called austerity case law has been praised by some commentators, but criticised by others who have accused the Court of insularity, inconsistency and of engaging in judicial activism. Other areas where transnational law has presented challenges include retroactive effect of EU regulations, publication of IMF decisions and international extraditions. The European Arrest Warrant and Data Retention Directive did not raise constitutional issues. Amendments of the Constitution with a view to EU and international co-operation are extensive. These include removal of several programmatic provisions regarding the social orientation.

Francisco Pereira Coutinho is Professor at Faculdade de Direito da Universidade Nova de Lisboa (NOVA School of Law) and Member of CEDIS – Centre for Research in Law and Society. e-mail: fpereiracoutinho@fd.unl.pt.

Nuno Piçarra is Professor at Faculdade de Direito da Universidade Nova de Lisboa (NOVA School of Law) and Member of CEDIS – Centre for Research in Law and Society. e-mail: np@fd.unl.pt.

Francisco Pereira Coutinho wrote Part I, Part II (Sections 2.4, 2.5, 2.7 and 2.8.1) and Part III. Nuno Piçarra wrote Part II (Sections 2.1–2.3, 2.6, 2.8.2–2.8.6, 2.9, 2.10–2.13).

All websites accessed 1 March 2015. Text submitted 24 August 2015.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- The Constitution of Portugal

- Constitutional amendments regarding European and international integration

- The Portuguese Constitutional Court

- Constitutional review statistics and grounds

- Fundamental rights and the rule of law

- European Union and IMF austerity programmes

- The principles of legal certainty, legitimate expectations and non-retroactivity

- Social rights and the social state

- European Arrest Warrant

- Data Retention Directive

- Publication of IMF decisions

1 Constitutional Amendments Regarding EU Membership

1.1 Constitutional Culture

1.1.1 The Portuguese Constitution was, and to some extent still is, a by-product of the revolutionary years that followed the military coup that overthrew the authoritarian right-wing regime of the ‘Estado Novo’ (1926–1974). The ‘Carnation Revolution’ was made by middle-rank military officers but was quickly taken over by leftist political parties and movements. The military organised under a movement called ‘Movimento das Forças Armadas – MFA’ (‘Movement of the Armed Forces’).

An assembly was democratically elected on 25 April 1975 to enact a new constitution, but during the following year its proceedings were heavily influenced by the military. Two pacts with the main political parties represented in the assembly were signed to assure that the ‘spirit’ of the revolution was not lost. The Constitution that entered into force on 25 April 1976 stated that the MFA exercised sovereign powers in order to safeguard the conquests of the revolution, and foresaw the creation of the ‘Council of the Revolution’ (Conselho da Revolução). The latter was composed of military officers and had the competence to review the constitutionality of laws.

The 1976 Portuguese Constitution shares some of the main features of the constitutions adopted after the fall of an authoritarian regime, such as detailed rules and enforceability in court. From the outset it was also very programmatic and ideological, as it was envisioned as a transitional tool for the creation of a socialist society through the collectivisation of the means of production.Footnote 1 Some of the most ideological provisions were removed in 1982, and others became obsolete after the accession to the European Communities in 1986.

The extent of the revolutionary DNA that remains is still a topic of contention in Portugal. As we will see below, it was tested in the context of the constitutionality review of the austerity measures adopted after the 2011 international bailout.

Portuguese constitutional culture is mostly influenced by continental constitutional traditions. The French constitutional experience was preferentially chosen for the adoption of the main tenets of the political system and the organisation of the state. Germany’s fundamental law was mirrored for the basic principles of the rule of law and the protection of fundamental rights.Footnote 2

1.1.2

Article 1 of the Portuguese Constitution establishes that ‘Portugal shall be a sovereign Republic, based on the dignity of the human person and the will of the people and committed to building a free, just and solidary society’.Footnote 3 The next 295 articles establish the sovereignty and organisation of the state and, simultaneously, limit its powers through the protection of individual rights and liberties, the adoption of the rule of law and the separation of powers with due checks and balances. The Constitution also encapsulates the core values of the political community, which is to achieve an ‘economic, social and cultural democracy’ (Art. 2). To this end, the state is given a wide range of objectives in several programmatic provisions that recognise a vast array of social and cultural rights, such as the right to employment (Art. 58), social security (Art. 63), health (Art. 64), housing (Art. 65) and education (Art. 73). The Portuguese Constitution inaugurated a tradition of ‘analytical constitutional texts’ that was quickly followed in Spain (1978) and Brazil (1988), which are characterised by the thoroughness of the constitutional provisions and by the inclusion of novel subject matters in the Constitution.Footnote 4

None of the main purposes of the Constitution could be said to have an edge over the others.

1.2 The Amendments of the Constitution in Relation to the European Union

1.2.1 The original version of the text of the 1976 Portuguese Constitution did not mention European integration. Although arguably the majority of the Portuguese political elites were then already pro-European, the correlation of forces was still dominated by Marxist political parties and the military. The latter was able to impose some ideas that were simply at odds with accession to a political project that pursued the creation of a single market based on liberal fundamental freedoms. The ‘transition to socialism’ was declared as an objective of the state (Art. 2). A mixed economic model was adopted, which included several provisions inspired by the socialist experiences of the former Eastern socialist bloc, such as the collectivisation of the sectors of production and wealth (e.g. Arts. 9(c) and 80) or the irreversibility of nationalisation carried out after the revolution, said to be ‘a conquest of the working class’ (Art. 83(2)).

An inconclusive doctrinal debate over the compatibility of the Constitution with the Treaties of Paris and Rome followed. Some argued for the introduction of structural amendments in the Constitution, especially in the economic chapter,Footnote 5 while others referred to a constitutional praxis that was already compatible with the European project.Footnote 6

The first constitutional amendments were introduced in 1982 also with the purpose of preparing a path for accession to the European Communities. The subsequent six constitutional revision processes were also based, albeit in different degrees of intensity, on the necessity to keep pace with the European integration project. For the sake of simplicity, the constitutional amendments related to European integration are schematically described in Table 1.

1.2.2 Title II of Part IV of the Constitution establishes two amendment procedures: (i) the ordinary, initiated by Parliament at least five years after the publication of the last ordinary constitutional revision law (Art. 284(1)); (ii) the extraordinary, initiated at any moment by a four-fifths majority of the Members of Parliament in exercise of their office (Art. 284(2)). In both cases, constitutional amendments need the approval of a two-thirds majority of the Members of Parliament who cast a vote (Art. 286). Of the seven constitutional revisions, three were extraordinary and motivated by the necessity to introduce amendments related to the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty (1992), the ratification of the Statute of the International Criminal Court (2001) and a referendum on the European Constitutional Treaty (2005).

1.2.3 Since the accession, we can identify three sets of amendments aimed at answering constitutional questions related to the EU.

The first regarded the democratic legitimisation of Portugal’s participation in the European integration process, namely through the adoption and continuous update of a provision that delegates the exercise of sovereign powers to the EU (Art. 7(6)) and through several amendments introduced to the legal framework for referendums to allow for a popular consultation on the text of the European treaties (Arts. 115(5) and 296).

The second set of amendments sought to tackle the problem of the so-called European democratic deficit. The intergovernmental nature of decision-making in the Council and the ever-increasing competences delegated to the EU challenged the pre-eminence of the national Parliament as ‘the house of Democracy’.Footnote 7 In 1992 and 1997 provisions were introduced to increase Parliament’s powers to monitor and exercise control over Governmental intervention within the European institutions.

The third set of amendments aimed at preventing conflicts between the Portuguese and the European legal orders. Some amendments were rather surgical and did not raise significant legal debates. This was the case for the amendment included in 2001 to allow for the adoption of the European Arrest Warrant (EAW).Footnote 8 Moreover, no relevant discussions arose regarding the obligation to transpose directives through legislative acts adopted in 1997 and 2004. This amendment was introduced to remove any doubts about the legal notice of national acts of European origin. Other amendments were more contentious, such as the transformations introduced in Art. 8 in order to prevent conflicts between constitutional law and EU law. Although the Constitution already contained a provision on the domestic incorporation of international law, that provision was specifically revised before Portugal’s accession to the European Communities so that it covered secondary law. It was further revised to resolve any doubts regarding the direct effect of directives in 1989 and on the magna question of the supremacy of EU law in 2004.

1.2.4 Most of the EU-related amendment proposals or constitutional reforms were enacted. Some, for example the amendment to the referendum procedure to allow for popular consultations on European treaties, were postponed for a while (see below Sect. 1.4.2), but materialised in the end. Recently, there was some discussion over the inclusion of the so-called deficit ‘golden rule’ adopted by the ‘Fiscal Compact’ in the Constitution, but no agreement was achieved between the main political parties to reach the necessary two-thirds majority to amend the Constitution (see below Sect. 2.7.1).

Notwithstanding the revision undertaken in 1989, several social and economic provisions of the Constitution are still regarded as in need of amendment to reflect the evolution of European integration. In this context, one constitutional scholar refers to an interpretative reorientation of the constitutional text in conformity with EU law in social and economic matters that could even lead to the ‘marginalisation or ignorance of constitutional provisions contrary or barely compatible with certain imperatives that stem from EU law’.Footnote 9

1.3 Conceptualising Sovereignty and the Limits to the Transfer of Powers

1.3.1 Article 7(6) of the Constitution governs the delegation of powers to the European Union by stating:

Subject to reciprocity and with respect for the fundamental principles of a democratic state based on the rule of law and for the principle of subsidiarity, and with a view to the achievement of the economic, social and territorial cohesion of an area of freedom, security and justice and the definition and implementation of a common external, security and defence policy, Portugal may agree to the joint exercise, in cooperation or by the Union’s institutions, of the powers needed to construct and deepen the European Union.

This provision develops the general commitment, expressed in Art. 7(5), to the reinforcement of the European identity and the strengthening of ‘European states’ actions in favour of democracy, peace, economic progress and justice in the relations between peoples’.

Supremacy and direct effect are indirectly recognised in Art. 8(4) of the Constitution:

The provisions of the treaties that govern the European Union and the norms issued by its institutions in the exercise of their respective competences are applicable in Portuguese internal law in accordance with Union law and with respect for the fundamental principles of a democratic state based on the rule of law.

1.3.2 The Portuguese Constitution follows a traditional notion of absolute sovereignty. Article 3(1) states that ‘sovereignty is single and indivisible and lies with the people’. This explains the absence of a clause for the transfer of sovereign powers to the EU. The majority of Portuguese constitutional scholars consider Art. 7(6) as a mere delegation of powers through inter-governmental cooperation.Footnote 10 It is as if European integration could be subsumed as ‘a mere participation in an inter-governmental process where the powers transferred by the States would be a priori clearly defined and subject to consensus decision-making’.Footnote 11 Remarkably, it was only on the eve of the ratification of the Maastricht Treaty, when the commitments assumed by the Portuguese state in the European integration process assumed a more pronounced political nature, that a provision regarding the exercise of competences by the EU was included in the Constitution. More recently, some authors have been advocating the need to recognise the EU’s claim of being an independent constitutional authority that exercises sovereign powers transferred by the Member States.Footnote 12

1.3.3 The delegation of powers to the European Union is limited by satisfaction of the general conditions set forth in Art. 7(6) of the Constitution, which include reciprocity, and respect for the fundamental principles of a democratic state based on the rule of law and for the principle of subsidiary. There are no specific limits to the extent of delegation.

The amendments introduced over the years in Art. 7(6) were aimed at legitimising Portuguese participation in European integration in areas more akin to the exercise of the state’s traditional sovereign competences.

1.3.4

Article 8(4) of the Constitution recognises that the legal authority of EU law in the Portuguese legal order must the established according to the parameters laid out by the EU legal order. This recognition is not unconditional, as it must comply with the fundamental principles of a democratic rule of law. In other words, the Portuguese Constitution recognises the primacy of EU law as long as both legal systems are compatible in systemic terms. This compatibility can be found in the mutual respect of the fundamental principles of a democratic rule of law. This means that the recognition of the supremacy of EU law in Art. 8(4) is not a constitutional capitulation, as it is limited by respect of the fundamental values of the Portuguese constitutional order. It is precisely this systemic identification between these two legal orders that will ultimately prevent the existence of any conflicts of normative authority.Footnote 13

The Constitutional Court has declared that the legislative branch is bound to respect the obligations stemming from EU law,Footnote 14 but has never accepted the supremacy of EU law over the Constitution. However, it has always shown restraint in reviewing the constitutionality of EU law. The Court seems to follow the generalised perception within Portuguese legal doctrine that the core legal values of the Portuguese Constitution are shared by the EU legal order and, therefore, it is unlikely that an EU legal act will go against the Constitution. This reasoning was clear in a decision from 14 August 2014. The case concerned the review of austerity measures which the Government contended were implemented to comply with binding recommendations of the European Commission adopted in the context of an excessive deficit procedure initiated against Portugal in January 2010. The Constitutional Court declared that the applicable EU law only set objectives to be reached by the Member States, and added that:

In a multilevel Constitutional system, in which several legal orders interact, internal legal norms cannot breach the Constitution (being that it is for the Constitutional Court, according to the Constitution, to administer justice in constitutional matters).

EU law respects the national identity of the Member States, reflected in the fundamental political structures of each of them [Art. 4(2) TEU]. Moreover, in this case there is no disagreement between EU law and Portuguese constitutional law. The Constitutional principles of equality, proportionality and the protection of legitimate expectations that have been used by the Constitutional Court to assess the constitutionality of internal norms in matters related to those that are being reviewed are at the core of the rule of law and the common European legal traditions that also bind the EU.Footnote 15

1.4 Democratic Control

1.4.1 Parliamentary control of Governmental participation in the EU’s decision-making procedure was marginal until the approval of Law 43/2006 of 25 August 2006 regarding the intervention of the Portuguese Parliament (Assembleia da República) within the scope of the process of constructing the European Union. This law, with the amendments introduced in 2012 (Law 21/2012 of 17 May), transformed the Portuguese Parliament into by far the most active Parliament based on the number of opinions sent to the European Commission,Footnote 16 especially after the adoption of an ‘enhanced scrutiny procedure’ in 2010 by the European Affairs Committee (EAC) for what it regards as priority initiatives.Footnote 17 The assessment procedure for European legislative initiatives takes a maximum of eight weeks and is better described in the following diagram (Fig. 1).

European legislative initiatives assessment procedure (Source European Affairs Committee (http://www.en.parlamento.pt/). Reproduced with the authorisation of the Portuguese Parliament.) The abbreviations refer to the following: AR – Portuguese parliament; EAC – European Affairs Committee; LAAR – Legislative Assemblies of the Autonomous Regions.

The EAC receives draft legislative initiatives sent by the European institutions or by the Government. The latter is obliged to keep Parliament informed of any relevant European legislative initiatives and is bound to ask for an opinion whenever such initiatives fall within the scope of Parliament’s reserved legislative competence (see Arts. 164 and 165 of the Constitution). The EAC then sends the draft legal acts to the parliamentary standing committees that are competent on the matter and, eventually, to the Legislative Assemblies of the Autonomous Regions, which have to be consulted if the subject matter of the draft legal act falls within their sphere of competence. After the reception of the report made by the parliamentary standing committee(s), the EAC approves a final written opinion. The written opinion, together with the report of the competent committee, is sent by the President of the Parliament to the European institutions and to the Government. If the draft legal act is deemed to breach the principle of subsidiarity or is considered to be politically relevant, the EAC will submit a draft resolution for the approval of the Plenary of Parliament. This procedure is applicable mutatis mutandis to the scrutiny of other European initiatives.

Parliament has proven extremely effective in monitoring EU policy documents and proposals for action, but less so in detecting breaches of the principle of subsidiarity. In fact, the number of reasoned opinions on the application of the principle of subsidiarity (Protocol 2 to the EU Treaties) has averaged only one a year, which is below the average of other European parliaments.

1.4.2

Since accession, the idea of calling a referendum on European integration has been discussed but has never materialised. At the time of accession, the Constitution only foresaw local referendums. The 1989 amendments introduced national referendums, but did not allow the people to be called upon to decide on questions included in international treaties. After two failed attempts to amend the Constitution for this purpose in 1992 and in 1994, the possibility of a referendum on matters included in international treaties was introduced in 1997. However, the referendum could not be on the text of the treaty itself. For that reason, two proposals for a referendum on the Amsterdam Treaty (1997) and on the Constitutional Treaty (2004) were both rejected by the Constitutional Court, with the argument that the questions drafted by Parliament were misleading.Footnote 18 To overcome this legal hurdle, in 2005 an extraordinary constitutional revision procedure was initiated to include the possibility of consulting the people directly on the text of a treaty aimed at deepening European integration (Art. 295).Footnote 19 Ironically, no vote was called on the Constitutional Treaty because other Member States in the meantime had abandoned its ratification, after popular rejections in France and in the Netherlands in the spring of 2005. Notwithstanding all the efforts to let the people have a direct say on Europe, political constraints determined that in 2008 a referendum was not called in the process of ratification of the Lisbon Treaty. More recently, on 12 June 2012, proposals for a referendum on the ‘Fiscal Compact’ treaty were also rejected by Parliament; it is likely that this proposal would have been rejected by the Constitutional Court, as the Constitution does not allow for referendums that concern budgetary or financial issues (Art. 115(4)(b)).

1.5 The Reasons for, and the Role of, EU Amendments

1.5.1

Although the Portuguese constitutional amendment procedure is very rigid – it establishes several formal, material and temporal conditions – the Portuguese constitutional culture is very favourable to the introduction of constitutional amendments as soon as a question of importance for society emerges. This is probably connected to a contentious constitutional history and to the lack of a national consensus on the original text of the 1976 Constitution, which soon became disconnected from the mainstream political choice towards European integration. Amendments were introduced to legitimise this option and to prevent conflicts with EU law.

European integration is a common trend in Portuguese constitutional revision procedures. In 1982 amendments were introduced to pave the way for accession to the European Communities. In 1989, 1992, 2001 and 2004 a systemic revision of the Constitution was implemented in order to prevent the risk of collisions with the EU legal order. These revisions involved the suppression of national provisions that could breach EU law (1989, 1992 and 2004) and a limited recognition of the supremacy of EU law (2004). Finally, the constitutional revisions of 1997 and 2005 were justified by the will to legitimise European integration through a referendum (1997 and 2005) and by the need to include safeguards to guarantee the democratic control of the actions of the Government in the European institutions (1992, 1997 and 2004).

1.5.2 Not applicable (see Sect. 1.5.1).

1.5.3

Over the years, constitutional amendments have been introduced ex ante to reflect treaty developments in the EU. For this reason, some argue that Treaty ratification reflects the only real exercise of constitutional authority in Europe.Footnote 20 This position, which is a reminiscence of a classic voluntaristic public international law perspective according to which no effects could emerge from treaties except those expressly foreseen by states, stems from a conception of absolute sovereignty that is still enshrined in Art. 3(1), but contradicts the constitutionalisation process that is ongoing both in the international and European legal sphere. The introduction of Art. 8(4) may have been a turning point. This provision indirectly recognises the autonomy of the European legal order. It was within this novel legal framework that the Constitutional Court mentioned the existence of a ‘multilevel constitutional system’Footnote 21 and referred to the principle of supremacy as imposing obligations that emerge directly from EU law, as well as from Art. 8(4) of the Constitution.Footnote 22 This recognition does not imply a constitutional surrender. The Constitution remains the basic law that defines and protects the core values of the political community and the basic rights and liberties of individuals. This implies that the Constitutional Court is not bound to recognise the supremacy of a supranational legal order in the unlikely event of a breach of those values, rights and liberties.

2 Constitutional Rights, the Rule of Law and EU

2.1 The Position of Constitutional Rights and the Rule of Law in the Constitution

2.1.1

The 1976 Constitution begins with a general introductory part, titled ‘Fundamental Principles’. It includes the protection of human dignity and the rule of law and its corollaries or sub-principles: legal certainty, the protection of legitimate expectations and proportionality. Part I opens with a section dedicated to the general principles that belong to the regime governing fundamental rights: the principle of universality (Art. 12), the principle of equality (Art. 13), etc. This part of the Constitution includes an extensive and detailed (perhaps too detailed) catalogue of fundamental rights encompassing rights from the first to the fourth generation (Art. 24 to Art. 79). This catalogue distinguishes between (i) civil rights, freedoms and guarantees (safeguards), (ii) rights, freedoms and guarantees concerning political participation, (iii) workers’ rights, freedoms and guarantees and (iv) economic, social and cultural rights. Amongst civil rights, freedoms and guarantees, Arts. 27 to 32 provide extensive and detailed provisions on deprivation of liberty, defence rights and guarantees in criminal proceedings, on the application of criminal law and on limits on sentences and security measures. Such an extensive and detailed list of rights, freedoms and guarantees for the individual in the criminal justice system is unusual from a point of view of comparative constitutional law.

The dividing line between each of these sets of rights and freedoms is not always very clear, although it is possible to say that each of the sets delimits a field of human activity: personal life, political life and work life.Footnote 23

The so-called ‘rights, liberties and guarantees’, be they civil, of political participation or, more specifically, of workers, are submitted to a common legal framework (which does not extend to economic, social and cultural rights). This framework is foreseen in Art. 18(1), which states that the ‘Constitutional provisions with regard to rights, freedoms and guarantees shall be directly applicable to and binding on public and private persons and bodies’.

On that constitutional basis, such rights, freedoms and guarantees, as well as the above-mentioned principles, are generally enforceable in courts, and their enforcement by ordinary courts may be submitted to a final review by the Constitutional Court (see above Sect. 1.1.2).

Furthermore, Art. 21 states that everyone has ‘the right to resist any order that infringes their rights, freedoms or guarantees and, when it is not possible to resort to the public authorities, to use force to repel any aggression’.

2.1.2 The constitutional provisions stipulating the conditions under which restrictions can be imposed on rights are found in Art. 18(2) and (3). They provide:

A statute may only restrict rights, freedoms and guarantees in cases expressly provided for in this Constitution, and such restrictions shall be limited to those needed to safeguard other rights and interests protected by this Constitution. … Statutes restricting rights, freedoms and guarantees shall possess an abstract and general nature and shall not have a retroactive effect or reduce the extent and the scope of the essential content of the provisions of this Constitution.

2.1.3 According to Art. 2 of the Constitution, the Portuguese Republic is a democratic state based on the rule of law, the sovereignty of the people, on plural democratic expression and organisation, on respect for and the guarantee of the effective implementation of fundamental rights and freedoms, and the separation and interdependence of powers.

Jurisprudence and legal literature conceptualise the rule of law as a structuring constitutional principle encompassing a variety of sub-principles: not only legal certainty, proportionality, non-retroactivity and legitimate expectations, as already mentioned, but also the separation of powers (Art. 111(1)), the independence of judicial power (Art. 203) and access to law and effective judicial protection as established in the detailed Art. 20. The rule of law principle is normally justiciable through its sub-principles. The argument of the violation of, for instance, the principle of proportionality, contained within the principle of the rule of law in Art. 2 of the Constitution, is frequently invoked by applicants and by ordinary courts exercising judicial review of constitutionality under Art. 204, and naturally by the Constitutional Court, as ‘the court with specific responsibility for administering justice in matters of legal and constitutional nature’, under Art. 221.

Access to courts and the right to judicial review are foreseen by Art. 20(1), according to which everyone shall be guaranteed access to the law and the courts in order to defend their rights and legitimate interests, and justice shall not be denied to anyone due to a lack of financial means. The same article also states that everyone has the right to secure a ruling in any lawsuit to which he or she is a party, within a reasonable period of time and by means of a fair process (para. 4).

The rule that only published law can be enforced, the rule that any imposition of obligations, administrative charges or penalties and criminal punishments is only permissible on the basis of a parliamentary statute or of a governmental legislative act previously authorised by Parliament, and the rule according to which sanctions cannot be applied either retroactively or by analogy, are also considered as core elements of the rule of law principle (and incorporated e.g. in Art. 103(2) and (3) regarding the tax system).

2.2 The Balancing of Fundamental Rights and Economic Freedoms in EU Law

2.2.1 Until the zenith of the financial crisis in Portugal in 2010, which culminated in an international bailout in the first semester of 2011, the balancing of constitutional fundamental rights with economic free movement rights did not raise noteworthy issues. Since then and especially within the framework of the privatisation of relevant public enterprises with their shares made available for acquisition by foreign economic entities, the balancing of the main constitutional goods at stake is becoming more controversial: on the one side, the freedom of establishment – inasmuch as it allows the possibility of transferring the head office of a privatised enterprise to another Member State; on the other side, the fundamental rights of workers, and namely their right to take collective action, which are possibly affected or limited by such transfer. In cases such as the privatisation of TAP Air Portugal (the national airline), these questions were openly discussed.

It has yet to be seen if the national courts will adjust their balancing towards generally favouring workers’ rights over economic freedoms to match the approach of the Court of Justice (ECJ).

2.3 Constitutional Rights, the European Arrest Warrant and EU Criminal Law

2.3.1 The Presumption of Innocence

2.3.1.1

According to Art. 32(2) of the Constitution, ‘[e]very defendant shall be presumed innocent until a sentence has been pronounced, and shall be brought to trial as quickly as it is compatible with the safeguards of the defence’. We are not aware that such constitutional provision has been invoked in the Portuguese legal literature or in the case law in the context of the European Arrest Warrant (EAW) with a view to raising concerns about a hypothetical weakening or jeopardising effect of the EAW on the principle of the presumption of innocence.

Therefore, a conclusion that such principle can no longer be fully granted the same level of protection as prior to the entry into force of the EAW Framework DecisionFootnote 24 (EAW FD) cannot be drawn. In the context of the Portuguese experience with the EAW, that conclusion seems indefensible. Furthermore, it presupposes an ideological conception, according to which beyond the framework of the national state the protection of fundamental rights and liberties is always weaker than inside, and therefore such shift represents a loss in terms of the rule of law.Footnote 25

2.3.1.2 In the context of the execution of international conventions on extradition binding on the Portuguese state, national judges must be more ‘pro-active’ than in the framework of the EAW. As a matter of fact, in the context of extradition they have to observe constitutional provisions that are not applicable to the EAW by virtue of Art. 33(5) of the Constitution. According to the latter, the provisions of the previous paragraphs of Art. 35 (limiting extradition) shall not ‘prejudice the application of such rules governing judicial cooperation in the criminal field as may be laid down under the aegis of the European Union’, and namely the rules of transposition of the EAW FD.

It follows that cases of refusal of extradition are more frequent than cases of refusal of execution of an EAW. In the former, revision of evidence by the courts is not excluded when the person whose extradition is requested claims his or her innocence.

2.3.2 Nullum crimen, nulla poena sine lege

2.3.2.1 Article 29(1) of the Constitution provides that ‘[n]o one shall be sentenced under the criminal law unless the action or omission in question is punishable under the terms of a pre-existing law, nor shall any person be the object of a security measure unless the prerequisites therefor are laid down by a pre-existing law’.

The fact that the list in Art. 2(2) of the EAW FD includes merely ‘types’ and not well-defined offences does not jeopardise eo ipso the principle nullum crimen.Footnote 26 As a matter of fact, such types are not directly applicable, and the national criminal law cannot include ‘types’ but only precisely defined offences, according to the principle of legality, which is very strict in this context. As the ECJ stated in Advocaten voor de Wereld:

… even if the Member States reproduce word-for-word the list of the categories of offences set out in Article 2(2) of the Framework Decision for the purposes of its implementation, the actual definition of those offences and the penalties applicable are those which follow from the law of ‘the issuing Member State’. The Framework Decision does not seek to harmonise the criminal offences in question in respect of their constituent elements or of the penalties which they attract.

Accordingly, while Article 2(2) of the Framework Decision dispenses with verification of double criminality for the categories of offences mentioned therein, the definition of those offences and of the penalties applicable continue to be matters determined by the law of the issuing Member State, which, as is, moreover, stated in Article 1(3) of the Framework Decision, must respect fundamental rights and fundamental legal principles as enshrined in Article 6 EU, and, consequently, the principle of the legality of criminal offences and penalties. Footnote 27

The Portuguese act transposing the EAW FD (Law 65/2003 of 23 August) reproduces the list of the categories of offences set out in Art. 2(2) of the EAW FD, but the Criminal Code defines, in strict conformity with the legality principle, such offences and the penalties applicable.

In any case, it should not be forgotten that the offences included in the EAW FD list, due to their gravity, are inevitably foreseen by the criminal laws of the Member States, and some of them had already been harmonised at EU level before the entry into force of the EAW FD. Furthermore, this legislative harmonisation did not stop after the entry into force of the EAW FD, since its development is crucial in this area, as the TFEU itself recognises in Art. 82(1). According to this provision, ‘judicial cooperation in criminal matters in the Union shall be based on the principle of mutual recognition of judgments and judicial decisions and shall include the approximation of the laws and regulations of the Member States in the areas referred to in para. 2 and in Art. 83’. The latter coincide largely with the offences listed in Art. 2(2) of the EAW FD.

At the level of national case law, the Portuguese Supreme Court of Justice, in a judgment of 4 January 2007, held that the abolition of the double criminality test presupposes that the executing authority verify, in accordance with the principles of trust and mutual recognition, whether the acts underlying the EAW, as qualified by the issuing authority, integrate the ‘material domains of criminality’ defined in Art. 2(2) of the EAW FD or are rather ‘manifestly beyond them’.Footnote 28 In the latter cases, where double criminality is effectively absent, it is generally assumed by the national courts that such a situation constitutes a ground for optional and not mandatory non-execution. This solution has given rise to criticism in the legal literature, which generally considers that non-execution is mandatory in such cases.Footnote 29

In any case, a conclusion that the principle of nullum crimen can no longer be fully granted the same level of protection as prior to the entry into force of the EAW FD does not seem objectively permissible in this context. The observation made above (Sect. 2.3.1.1) is fully transposable to this context: such conclusion would be mainly ideological and not based on sound evidence.

2.3.3 Fair Trial and In Absentia Judgments

2.3.3.1 According to Art. 32(6) of the Constitution, ‘[t]he law shall define the cases in which, subject to the safeguarding of the rights of defence, the presence of the defendant or the accused at procedural acts, including trial hearings, may be dispensed with’. It follows that in absentia judgments, being exceptional, are not necessarily contrary to the Constitution and to the safeguards for the defence that criminal proceedings must ensure by virtue of Art. 32(1).

Furthermore, that constitutional provision is in accordance with the ECHR jurisprudence according to which the right of the accused to appear in person at the trial is not absolute, and under certain conditions the accused may, of his or her own free will, expressly or tacitly but unequivocally waive this right.

The cases of judgments in absentia foreseen by the EAW FD as amended by FD 2009/299/JHA of 26 February 2009, which do not allow the executing authority of a Member State to impose conditions on the execution of an EAW issued by another Member State, are cases of so-called false in absentia judgments where:

-

(i)

the person was summoned in person and thereby informed of the scheduled date and place of the trial which resulted in the decision and was informed that a decision might be handed down if he or she did not appear for the trial;

-

(ii)

the person was not summoned in person but by other means actually received official information of the scheduled date and place of the trial which resulted in the decision, in such a manner that it was unequivocally established that he or she was aware of the scheduled trial, and was informed that a decision might be handed down if he or she did not appear for the trial;

-

(iii)

being aware of the scheduled trial, the person had given a mandate to a legal counsellor, who was either appointed by the person concerned or by the state, to defend him or her at the trial, and was indeed defended by that counsellor at the trial.

In these cases, the execution of an EAW by a national court does not raise any constitutional issues and does not prompt any revisiting of the established standards of protection.

2.3.4 The Right to a Fair Trial – Practical Challenges Regarding a Trial Abroad

2.3.4.1 Beyond standard consular assistance, the Portuguese state does not usually provide assistance to its extradited citizens or residents.

The introduction of a publicly funded state or non-governmental body to provide assistance to residents of Portugal who are involved in trials abroad could make sense, especially in cases where the state in which the trial is held is not governed by the rule of law, or where the death penalty is applicable. The criteria for the intervention of such a body should be very clear in order to limit it to cases where it would be indispensable. In principle, the intervention of such body would be excluded regarding trials in other EU Member States, considering the general safeguards of defence ensured in the framework of their criminal proceedings.

2.3.4.2 We were unable to gather data concerning the number of individuals extradited by Portugal who have subsequently been found innocent.

2.3.5 The Right to Effective Judicial Protection: The Principle of Mutual Recognition in EU Criminal Law and Abolition of the Exequatur in Civil and Commercial Matters

2.3.5.1 The move to mutual recognition is not incompatible with the requirements of the rule of law and the right to effective judicial protection, provided that the states among which mutual recognition is put in effect are themselves governed by the rule of law and guarantee the right to effective judicial protection, as are and do in principle the EU Member States.

Contrary to the idea that underlies this questionnaire, a supranational or transnational framework of judicial cooperation in criminal matters does not necessarily imply a loss or a minus in terms of the rule of law when compared with the national framework. In the legal framework of the EU, mutual recognition should even be taken as an opportunity to improve the rule of law in the Member States. For instance, if in a Member State there is a deficit in judicial protection, the fact that the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (Charter) and its Art. 47 (‘Right to an effective remedy and to a fair trial’), which are fully justiciable, become applicable in the context of the issuing and execution of an EAW can contribute to improving such deficit at the national level.

Since a right of appeal is an essential element of the right to effective judicial protection (according to Art. 29(1) of the Constitution, the right to appeal is a necessary safeguard for the defence in criminal proceedings), it has to be put in ‘practical accordance’ (balanced) with the principle of mutual recognition. Although ‘the full exercise of the right of defence against the accusation must take place in the courts of the issuing State, because the EAW is based on the principles of judicial cooperation between Member States, mutual recognition of their respective legal systems and trust between the said States’,Footnote 30 if such defence really does not take place, it is the duty of the executing judge of the other Member State to guarantee that Art. 47 of the Charter is not violated in that case. The same is applicable mutatis mutandis to civil and commercial matters.

For all these reasons, the answer to the sacramental question whether a conclusion can be drawn that the principle of effective judicial protection and the rule of law can no longer fully be granted the same level of protection as prior to the introduction of the mutual recognition rule in criminal law and the abolition of the exequatur in civil and commercial matters, is negative.

2.3.5.2 It is a fact that the principle of mutual recognition was an ECJ creation in the framework of the freedom of movement of goods when it was not yet decided whether that freedom of the common market presupposed the general harmonisation of national legislation on the production and commercialisation of goods, or could coexist with different national legislation on those matters. In that context, the principle of mutual recognition rendered a considerable quantity of EU harmonising legislation unnecessary.

It was with the purpose of limiting the legislative competence of the EU that the principle of mutual recognition was extended to the fields of judicial cooperation in criminal and civil matters. However, the material differences between those areas and the internal market have as a consequence that the necessity of approximation of the laws of the Member States is much higher in the former areas than in the latter. While in the internal market mutual recognition can be seen as a real alternative to approximation of the legislation of the Member States, in the areas of judicial cooperation in criminal and civil matters, one of the indispensable conditions for the effectiveness of the principle of mutual recognition of judgments and judicial decisions is that such judgments and decisions are based on harmonised legislation reflecting the same fundamental substantive and procedural principles.Footnote 31

In conclusion, in the areas of judicial cooperation in criminal and civil matters mutual recognition and legislative harmonisation are more closely associated than in other areas. These are the main aspects of the national debate.

2.3.5.3 For all the above mentioned reasons, a supposed change in the role of the Member States’ courts, from providing judicial protection against unwarranted national measures to becoming actors of loyal co-operation, efficiency and trust as ‘EU law courts of ordinary jurisdiction’ is, in our view, somewhat of a false dilemma. Mutual recognition does not suppress the fundamental role of every court to protect against illegal measures.

The EAW FD is sufficiently clear on this point. According to its recital 12, nothing in the EAW FD

may be interpreted as prohibiting refusal to surrender a person for whom a European arrest warrant has been issued when there are reasons to believe, on the basis of objective elements, that the said arrest warrant has been issued for the purpose of prosecuting or punishing a person on the grounds of his or her sex, race, religion, ethnic origin, nationality, language, political opinions or sexual orientation, or that that person’s position may be prejudiced for any of these reasons.

Furthermore, according to Art. 1(3), ‘[t]his Framework Decision shall not have the effect of modifying the obligation to respect fundamental rights and fundamental principles as enshrined in Article 6 of the Treaty on European Union’. An evolutionary approach to this provision obliges the interpreter to add the following normative segment: ‘and as enshrined in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union’.Footnote 32

2.3.5.4 Extradition requests for trivial offences should not happen, simply because the relevant conventions generally exclude ‘trivial offences’ from their scope. The required courts must deny requests for extradition that are not based on the applicable convention, as duly interpreted.

In the context of the EAW, the FD is clear. According to Art. 2(1), ‘[a] European arrest warrant may be issued for acts punishable by the law of the issuing Member State by a custodial sentence or a detention order for a maximum period of at least 12 months or, where a sentence has been passed or a detention order has been made, for sentences of at least four months’. Such acts are not, in principle, ‘trivial offences’.

In our view, recommendations that undermine the essential logic of the EAW should not be supported. On the other hand, concerning the classic institute of extradition, several forms of judicial and political review are foreseen by the applicable conventions aimed at ensuring that there is sufficient evidence that the offence is sufficiently serious and that there is a sufficient link between the offence and the country to which the individual is extradited.

There is no point to call for amendments in the extradition legal framework when the reasonable solutions already flow from this framework.

2.4 The EU Data Retention Directive

2.4.1 The Portuguese Constitution protects the privacy of personal life in Art. 26(1), according to which

[e]veryone shall possess the right to a personal identity, to the development of their personality, to civil capacity, to citizenship, to a good name and reputation, to their likeness, to speak out, to protect the privacy of their personal and family life, and to legal protection against any form of discrimination.

According to Art. 35(4), ‘[t]hird-party access to personal data shall be prohibited, save in exceptional cases provided for by the law’. Article 34(1) proclaims that ‘[p]ersonal homes and the secrecy of correspondence and other means of private communication shall be inviolable’, and Art. 32(8) forbids evidence obtained by improper tampering with personal telecommunications. Limits to the privacy of electronic communications may be allowed in criminal cases (Art. 34(4)). Any restriction has to be established by law, which has to be necessary, abstract, general and cannot have retroactive effect or reduce the extent or the scope of the essential content of the constitutional right to privacy (Art. 18(2) and (3)).

Law 32/2008 of 17 July that transposed the EU Data Retention Directive 2006/24Footnote 33 is in force. It was never contested prior to the annulment of the directive, and it is unlikely to be challenged based on the rules regarding safeguards for access to and time limits for data retained. Data are preserved for one year and can only be accessed with the permission of a judge (Arts. 6 and 7 of Law 32/2008). This explains why Portugal has only had a few hundred requests for access to data retained compared to millions in the United Kingdom.Footnote 34

Prior to the decision of the ECJ that invalidated the EU Data Retention Directive 2006/24, it was unclear whether the rule on blanket data protection was compatible with the Constitution. In 2010, a decision of the Portuguese Supreme Court of Justice adopted a strong stance against ‘fundamental readings’ of the right to privacy that could jeopardise the safety of the community.Footnote 35 After the Digital Rights decision,Footnote 36 this position is no longer sustainable.

Law 32/2008 still implements EU law, even if it was originally enacted to transpose an EU legal act that has in the meantime been invalidated.Footnote 37 It thus falls within the scope of the Charter (Art. 51). As ‘EU law courts of ordinary jurisdiction’, Portuguese courts are thus under the obligation to apply the principle of supremacy and trump its application.

Moreover, the Constitutional Court, if called to decide on the constitutionality of Law 32/2008 of 17 July, would be likely to declare the unconstitutionality of the latter, with the argument that automatic blanket retention of data for one year is a mechanism of ‘mass surveillance’ that involves a disproportionate restriction on the right to privacy (Art. 26(1) of the Constitution), since it allows for the retention of data of citizens who are not involved in any criminal activity (Art. 34(4) of the Constitution). Such a decision would follow its case law that recognises the existence of a ‘multilevel’ system of protection of fundamental rights,Footnote 38 but it could have the effect of reopening criminal cases that have been decided based on access to data retained under Law 32/2008.

2.5 Unpublished or Secret Legislation

2.5.1 We are unaware of any cases concerning the constitutionality of unpublished or secret measures. Article 119(2) of the Constitution establishes that unpublished legal acts ‘do not have legal force’. This means that they are valid but cannot produce any effects on individuals.Footnote 39

2.6 Rights and General Principles of Law in the Context of Market Regulation: Property Rights, Legal Certainty, Non-retroactivity and Proportionality

2.6.1 Until the recent economic and financial crisis, issues regarding constitutional standards of protection of property rights, legal certainty, legitimate expectations, non-retroactivity and proportionality had arisen rarely in practice in relation to EU measures on market regulation (some cases regarding constitutional non-retroactivity of tax law in the case of an EU legislative corrigendum are summarised below 2.8.1).

2.7 The ESM Treaty, Austerity Programmes and the Democratic, Rule-of-Law-Based State

2.7.1

Capital calls that could be requested from Portugal under the Treaty Establishing the European Stability Mechanism (ESM Treaty) amount to a maximum of 17,564,400,000 EUR,Footnote 40 or approximately 10% of the annual GDP (at market prices) and 9% of the annual state budget (2013).Footnote 41 Notwithstanding these impressive figures, in the parliamentary commission reports we found no reference to specific constitutional problems related to this financial commitment of the Portuguese state under the ESM Treaty.Footnote 42

Constitutional arguments were discussed during the ratification of the Fiscal Compact Treaty.Footnote 43 There were some discussions on the inclusion in the Constitution of annual limits to the public deficit and debt. Parliament decided to include such limits, but only in the ‘budget framework law’ (Law 91/2001 of August 20), which is an act that has a parametric nature in relation to ordinary laws (Art. 112(3)). Some concerns were also articulated regarding the powers at the disposal of the European Commission to determine substantive public policies in Member States that are experiencing budgetary and debt problems. A Member of Parliament declared that these powers breached the principle of national sovereignty, the principle of popular sovereignty, the principle of democracy and the principle of budgetary sovereignty.Footnote 44

2.7.2 With a crumbling banking sector and a chronic public debt, there is a wide agreement in Portugal in favour of Eurobonds and of a stronger Banking Union as quickly as possible. No relevant discussions have arisen with regard to potential constitutional problems related to exposure to other countries’ debt or banking failures.

2.7.3

The Portuguese Constitutional Court emerged during the financial crisis as a key protagonist in the political system when it had to address the compatibility with the Constitution of legislative acts that established increases in taxes and reductions of expenditures that included drastic cuts in the wages of public servants and in several social benefits, including pensions.

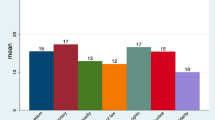

Austerity measures were enacted between mid-2010 and May 2011 to avoid an international bailout, between May 2011 and May 2014 to reflect the requirements of the Financial Assistance Programme set forth in several memoranda of understanding imposed by the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund (the so-called Troika), and have been enacted since May 2014 to comply with the Commission’s recommendations adopted in the context of an excessive deficit procedure initiated against Portugal in January 2010.Footnote 45 Table 2 portrays all of the high profile decisions taken by the Constitutional Court during this period.

The Portuguese Constitutional Court cannot be identified as a sort of ‘Don Quixote’ fighting the windmills of austerity. Such an image would be completely at odds with the fact that from the outset of the crisis, the Court made every effort to internalise the European and international obligations of the Portuguese state.Footnote 46 In case 396/2011, the Court declared that the austerity measures were important to enforce the Growth and Stability Pact obligations, in case 353/2012 the Court recognised (wrongly) that the memoranda signed by the Portuguese Government with international and European institutions were legally binding to the extent that they were based on international law and EU law instruments, and in case 602/2013 the Court went through a detailed examination of how the provisions under review were a result of a direct transposition of the memoranda into national law. More recently, in case 575/2014, although any declaration on the legal nature of the European Commission’s recommendations adopted in the context of the excessive deficit procedure was avoided, the Court considered that the objective set forth in the recommendations was binding (see above Sect. 1.3.4).

The Constitutional Court has always made the caveat that the austerity measures adopted during the international bailout to comply with the conditionality programmes imposed by the Troika were approved within the limits of the discretion given by international and European Union law. In other words, they were a direct result of a political option and, therefore, had to be reviewed according to the usual constitutional standards of adjudication. In this context, the Court rejected the adoption of a ‘crisis law’ criterion that would imply accepting the argument of the financial emergency of the state as a justification for austerity measures.Footnote 47 Instead it went through a case-by-case analysis of each measure, which determined the acceptance of some (mostly transitory) and the rejection of others because they breached the principle of equality, failed the proportionality test or did not meet legitimate expectations. This case law, which in several decisions was adopted with a slim majority inside the Court, was praised by some authorsFootnote 48 but contested by others who accused the Court of inconsistency and of engaging in judicial activism.Footnote 49

2.8 Judicial Review of EU Measures: Access to Justice and the Standard of Review

2.8.1

We found three cases since 2001 in which a preliminary ruling regarding the validity of an EU law act was requested by an applicant in a Portuguese court, but only in one was a preliminary reference sent to Luxembourg.

The first two were identical and concerned a corrigendum to Council Regulation (EC) 1771/2003 of 7 October 2003 regarding quotas for certain fishery products.Footnote 50 The corrigendum was published on 31 March 2004 and clarified that the quotas were applicable from the date of the entry into force of the regulation (13 October 2003) and not from the beginning of 2003, as it was stated in the original version of the regulation. The applicant in the national proceedings argued that the corrigendum had a retroactive effect and thus materially should be considered as an amendment and not a correction to the regulation. The corrigendum was thus deemed invalid by the national court, as it had not followed the EU legislative procedure, namely voting by qualified majority in the Council, and could not be considered as an EU legal act, since it was not foreseen in Art. 288 TFEU.Footnote 51

The Portuguese administrative court of appeal refused to apply the corrigendum based on a violation of the constitutional principle of the non-retroactivity of tax law (Art. 103(3) of the Constitution). These are, as far as we know, the first decisions on the unconstitutionality of an EU law act adopted in the Portuguese legal order. According to the Court:

the (EU) law provisions in question breach … the constitutional principle of non-retroactivity of tax law … Art. 204 of the Constitution grants a national judge the competence to judicially raise and declare the unconstitutionality and, therefore, the internal inapplicability of the (EU) law provision.Footnote 52

These decisions are also noteworthy because the Portuguese court went on to declare in an obiter dictum that the corrigendum was invalid but a preliminary reference was not mandatory: according to the ‘acte clair doctrine’ set forth in Cilfit, the grounds of invalidity argued by the applicant were said to be in these cases ‘completely clear’.Footnote 53

In the third case, the respondent in the national proceedings invoked several infringements of Art. 107 TFEU to argue for the invalidity of the Commission Decision 2011/346/EU of 20 July 2010 on the State aid C 33/09, which was implemented by Portugal in the form of a state guarantee to a bank. This claim was dismissed by the ECJ.Footnote 54

2.8.2

A systematic contrast in the standard of judicial review applied by the EU courts and by the Portuguese courts has not been generally perceptible until now. However, we should be aware of the possibility of a more serious and systematic contrast between the case law of the ECJ and that of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), with unavoidable repercussions on the scrutiny powers of the national courts. The most recent example is the judgment of the ECtHR, Tarakhel v. Switzerland,Footnote 55 of 4 November 2014, concerning the enforcement of the Dublin III regulation, which contrasts, to some extent, with the judgment of the ECJ in N.S. and Others.Footnote 56, Footnote 57

For its part, Opinion 2/13 of 18 December 2014 of the ECJ,Footnote 58 having seriously obstructed the accession of the EU to the ECHR, does not contribute to the solution of this problem. As it is well known, EU Member States are all Contracting Parties to the ECHR and in that quality they are bound by the latter, even when they enforce EU law. Furthermore, according to Art. 2 of Protocol No 8 relating to Art. 6(2) of the TEU on the accession of the Union to the ECHR, the agreement relating to this accession ‘shall ensure that nothing therein affects the situation of Member States in relation to the European Convention, in particular in relation to the Protocols thereto’.

It is to be seen if the above-mentioned divergences are sufficient to make a case for a stricter standard of judicial review of EU measures.

2.8.3 The Constitutional Court and the two Portuguese Supreme Courts (Supreme Court of Justice and Supreme Administrative Court) take in general a more deferential than vigorous approach to the review of constitutionality and of legality, oriented by a conception of self-restraint imposed by the principle of the separation of powers. The idea is that such courts do not want to become alternative legislators or administrators when exercising their judicial review.

This does not mean that a considerable number of legislative and executive acts are not annulled not only on grounds of lack of competence or infringement of formal or procedural requirements,Footnote 59 but also due to infringement of substantive constitutional law (fundamental rights and principles). Some of the judgments referred to above in Sect. 2.7.3 (Table 2) are good examples of annulment judgments of the Constitutional Court on grounds of the violation of the fundamental principles of equality, proportionality and the protection of legitimate expectations, as concretised by a previous, consolidated jurisprudence, which did not change substantially in those judgments (notwithstanding some occasional and limited adaptations). They also show that it is not correct to affirm in general terms that the Constitutional Court became significantly more vigorous in its approach during the economic and financial crisis and that it built upon the principles and tests developed before the crisis. It was rather the legislator, urged by the Memorandum of Understanding signed with the Troika, that revealed a controversial political will to go even ‘beyond the (bailout) agreement’.Footnote 60 This voluntary stance led to the adoption of a considerable number of austerity measures, including of budgetary nature (e.g. cuts in public servants’ wages, suspension of two months’ salary for public servants and pensioners, cuts in unemployment and health benefits) in contradiction with the above-mentioned constitutional principles, in their previously stabilised interpretation, on an unprecedented scale.

2.8.4 On several occasions the Constitutional Court and the two Supreme Courts have reviewed national measures implementing EU legislation through the application of internal constitutional and legal standards. Concerning EU measures, such courts have so far not expressly adopted a position similar to the German Constitutional Court’s Solange IIFootnote 61 judgment. However, Art. 7(6) of the Constitution – in so far as it subjects ‘the joint exercise, in cooperation or by the Union’s institutions, of the powers needed to construct and deepen the European Union’ to ‘respect for the fundamental principles of a democratic state based on the rule of law’ – creates a basis for a claim by the Constitutional Court of the competence to review, as a last resort, EU measures on grounds of inconsistency with one of those fundamental principles, in the not very likely case of failure to safeguard such principles at the EU level.

2.8.5 Article 2 TEU, in so far as it enumerates the list of common fundamental values and principles binding on the EU and also the Member States, allows, in principle, the Member States to fill any potential gap in judicial review. However, if the contrast between the case law of the ECJ and the case law of the ECtHR becomes aggravated, the national courts cannot continue to refrain from scrutinising acts of EU law from the perspective of their compatibility with the ECHR. As a matter of fact, Member States fully maintain their quality of Contracting Parties in that Convention in the sense that their obligations are not reduced or suspended because of EU membership. Moreover, with or without accession to the ECHR by the EU, the fundamental rights guaranteed by the ECHR are general principles of EU law. From this point of view, the use by national courts of the standard of human rights protection under the ECHR to scrutinise EU measures and not the standard used by the EU itself would not be problematic vis-à-vis the principle of sincere cooperation enshrined in Art. 4(3) TEU, even if through this kind of scrutiny the primacy, unity and effectiveness of EU law could eventually be compromised (see below Sect. 2.11.1).

Furthermore, in circumstances of a growing contrast between the case law of the ECJ and of the ECtHR, the latter might be led to re-examine its BosphorusFootnote 62 judgment.

2.8.6

The broader issue of equal treatment of individuals falling within the scope of EU law and those falling within the scope of domestic protection of constitutional rights is a permanent question which did not have to wait for the Advocaten voor the Wereld case to arise. This issue is very present for instance in respect to reverse discrimination or discrimination against a Member State’s own nationals who have not exercised their rights of free movement.

In our view, this ECJ judgment demonstrates sufficiently that the risk of discrimination within the scope of the EAW FD in what concerns the nulla poena sine lege principle is very low. In any case, the courts of the Member States in question have an important role to play in preventing such discrimination (see above Sect. 2.3.2).

2.9 Other Constitutional Rights and Principles

2.9.1 Article 165 of the Constitution describes the list of matters of exclusive legislative competence of the Portuguese Parliament. However, from Art. 165(1)(c) and (d) we can conclude that, subject to previous authorisation by Parliament,Footnote 63 the Government may legislate, through an executive law (Decreto-Lei), on the definition of crimes, sentences, security measures, criminal procedure, disciplinary infractions and administrative offences. This dichotomy between ‘exclusive responsibility of Parliament to legislate’ (reserva absoluta de competência legislativa) and ‘partially exclusive responsibility of Parliament to legislate’ (reserva relativa de competência legislativa) applies generally and was established in the Constitution before the accession of Portugal to the EU. These provisions must be read in conjunction with Art. 112(8) of the Constitution according to which ‘the transposition of European Union legislation and other legal acts into the internal legal system shall take the form of a law (lei), an executive law (decreto-lei), or … a regional legislative decree’ (see above Table 1, 1997).

2.10 Common Constitutional Traditions

2.10.1 Article 2 TEU in conjunction with the ECHR encompasses the so-called Europe-wide common constitutional traditions. Principles like nullum crimen, nulla poena sine lege, the right to judicial protection, the right to a fair trial, etc., should be regarded as corollaries of the principle of the rule of law and, to that extent, also as common constitutional traditions.

Some of these common traditions coexist with idiosyncratic elements resulting from a national constitutional identity or simply from the national history, as is the case, for instance, with the requirements for the protection of the dignity of the human person consecrated in the Bonner Grundgesetz. This was already recognised by the ECJ in the Omega judgment.Footnote 64

2.10.2 It should not be forgotten that the concept of ‘common constitutional traditions’ was adopted by the ECJ at a moment when the then European Communities were not bound by a catalogue of fundamental rights of their own. Since nowadays the EU is bound by Art. 2 and Art. 6 TEU and by the Charter of Fundamental Rights, which are largely based on the common constitutional traditions of the Member States, the latter tend to be absorbed by the former. Therefore, we do not see much merit in the proposition that national courts refer to national constitutions before questioning the ECJ in the framework of the preliminary ruling procedure, except in cases in which the fundamental right or principle invoked has an idiosyncratic element which is deemed to be essential to the constitutional identity of the Member State in question.

In any case, the Charter, for its part, foresees in broader terms in Art. 52(4) that in so far as the Charter recognises fundamental rights as they result from the constitutional traditions common to the Member States, these rights shall be interpreted in harmony with those traditions. This provision is obviously mandatory for the ECJ.

2.11 Article 53 of the Charter and the Issue of Stricter Constitutional Standards

2.11.1

According to Art. 52(3) of the Charter, in so far as the Charter contains rights that correspond to rights guaranteed by the ECHR, the meaning and scope of those rights shall be the same as those laid down by the said Convention. This provision does not prevent EU law from providing more extensive protection. It also does not preclude the existence of cases in which the standard is increased to match that provided under national constitutions. This is expressly allowed by Art. 53 of the Charter, although such authorisation cannot be interpreted as absolute or unlimited.Footnote 65

As the ECJ stated in the Melloni judgment, the application of national standards of protection of fundamental rights is allowed at the stage of implementing EU law, provided that the level of protection granted by the Charter, as interpreted by the said Court, and the primacy, unity and effectiveness of EU law are not thereby compromised.Footnote 66 This judgment confirms that Art. 53, in fine, must be balanced with the fundamental principles of the EU legal order, namely those enumerated by the ECJ in Melloni.Footnote 67 However, this is not incompatible with a presumption (juris tantum) in favour of a ‘more extensive protection’ allowed, but not imposed, by Art. 53 of the Charter.

In any case, it should not be forgotten that the highest protection ensured by EU law may be the protection established by the Charter, by the ECHR or by national constitutions, as there may be ‘differences between the legally relevant levels of protection that derive both from the texts and from their interpretation/practical application, done by the different judicial organs of the different levels of the system’.Footnote 68 In that context, it becomes clear that the ECHR, as interpreted by the ECtHR, does not necessarily provide a ‘minimum floor’ of protection of fundamental rights and that the Charter and national constitutions do not always provide a higher level of protection. If a right recognised by the ECHR, as interpreted by the ECtHR, which corresponds to a right guaranteed by the Charter, provides more extensive protection than the latter, the national courts, when they are implementing Union law, must enforce the right as interpreted by the ECHR. As a matter of fact, Art. 52(3) of the Charter does not prevent courts from providing more extensive protection than the ECHR, but prohibits such courts from providing less protection than the latter.

2.12 Democratic Debate on Constitutional Rights and Values

2.12.1 At the time of the national transposition of the EAW FD and of the Data Retention Directive there was a mild debate in the national Parliament concerning the conformity of the transposition acts with the fundamental rights granted by the Portuguese Constitution. In both cases, a parliamentary majority considered that these legislative acts were not incompatible with the Constitution.

2.12.2 The fact that a national Constitutional Court is confronted with ‘important constitutional issues’ ‘at the stage of implementing EU law’ obviously does not preclude the exercise of judicial review of the national measures at stake, eventually in dialogue with the ECJ. If the measures are of EU origin, their validity must be challenged before the ECJ through a request for a preliminary ruling. In parallel with this multilevel judicial review, the democratic debate about national measures implementing the contested EU law may proceed at national level.

2.12.3 If the cases in which important constitutional issues have been identified by a number of constitutional courts concern EU measures directly, those constitutional courts must request the ECJ to give a preliminary ruling on their validity and seize the opportunity to explain in detail why they think such EU measures should be invalidated. If the cases in which such important constitutional issues concern national measures implementing EU law, the constitutional courts are usually competent to review such national measures.

2.13 Experts’ Analysis on the Protection of Constitutional Rights in EU Law

2.13.1

We share concerns on the reduction in the standard of protection and in the rule of law in some domains where rights arise directly from EU law, such as in immigration and asylum (see above Sect. 2.8.2). However, we do not consider it accurate to declare that an overall reduction in the standard of protection of national constitutional rights in the context of or due to EU law has occurred.

That is in principle not the case with regard to the so-called ‘personal rights, freedoms and guarantees’ enumerated in Arts. 24 to 47 of the Constitution, nor with regard to the ‘rights, freedoms and guarantees’ concerning participation in politics established in Arts. 48 to 52 (see above Sect. 2.1.1). The same cannot be said about the ‘workers’ rights, freedoms and guarantees’ (Arts. 53 to 57) and the ‘economic, social and cultural rights’ (Arts. 58 to 79). The 2011 Memorandum of Understanding signed with the Commission – which may be considered binding EU lawFootnote 69 – had indeed as its object or effect a reduction in the standard of protection of some of such rights, freedoms and guarantees (see infra Sect. 3.5.1).

In any case, it should not be forgotten, on the one hand, that some of the national legislative and executive measures implementing the Memorandum were rejected by the Constitutional Court, such as, for instance, a legislative act foreseeing the dismissal of workers without fair cause, in flagrant contradiction with Art. 53 (which expressly prohibits such dismissal to protect job security; see above Table 2). On the other hand, it should be borne in mind that the implementation and enforcement of economic, social and cultural rights is made under the so-called ‘reserve of the possible’, i.e. under the constraints of the financial and material resources of the state or under a ‘certain empirical situation’.Footnote 70 Furthermore, the constitutional case law concerning such rights, freedoms and guarantees has always been cautious, contained and ‘condescending regarding the margins of political option of the legislator’.Footnote 71 Neither does such case law interpret the Constitution as establishing a general principle of prohibition of ‘social retrocession’ i.e. of reversibility of the economic, social and cultural rights, freedoms and guarantees, except when the object or the effect of the measure is to jeopardise the essential core of a minimal existence which is inherent to the respect for the dignity of the human person.Footnote 72