Abstract

The aim of this qualitative study was to test how social and cultural research methods can be used to anticipate opportunities and barriers to the use of consumer mobile devices by community health workers (CHWs) for HIV/AIDS prevention, testing and treatment. An exploratory study was conducted with CHWs (n = 19) at the regional capitals of Denpasar and Makassar in Indonesia in order to build to a clearer picture of how the participants have integrated personal mobile handsets into their daily professional and personal routine. A communicative ecologies framework was applied to the research design which included a range of qualitative methods including in-depth interviews, focus group discussions and communicative ecology mapping. Our main findings revealed that there was no bottom-up impetus for the introduction of a formal mHealth system to support client interactions. Existing client data collection systems were locked into paper-based systems to ensure compatibility with local government and/or funding body administrative systems; hence, mobile device-based data collection would require additional processes by the participants. Boundary issues were reported with regard to out of hours contact by clients. Some CHWs sent SMS medication reminders to clients but the strong preference indicated by all participating CHWs was to meet clients face-to-face in order to build and maintain trust through the in-person counselling process, rather than introduce mobile-mediated interaction.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

5.1 Introduction

This chapter reports on a bottom-up qualitative field study of everyday mobile device behaviours by HIV/AIDS community health workers (CHWs) in the regional capitals of Denpasar and Makassar in Indonesia. In contrast to the rural mHealth pilot described by Tariq and Durrani in Chap. 2, both sites of investigation feature comparatively good infrastructure in terms of mains power and network access, as well as ready availability of consumer mobile devices and affordable network tariffs. Hence, many of the barriers to scalability identified by Evans et al. in Chap. 3 (see Sect. 3.1) were not present at the sites of investigation in this study. Rather, all participants had personal mobile devices and most were at least moderate users of social networks. Therefore, the introduction of any consumer mHealth initiative at these sites which seeks to support health behaviour change across the lifespan will not only have to adapt to existing device and network availability and usage patterns but will also have to contend with the evolutions in devices and usage over the long-term.

As stated in the Introduction, a key aim of this book is to highlight how social and cultural research can play a more prominent role in understanding vernacular uses of mobile devices and their possible impact on mHealth programmes. In response to this aim, this chapter describes an exploratory study at two sites of investigation which used a communicative ecologies framework in order to build a clearer picture of existing mobile behaviours by CHWs working in the area of HIV/AIDS. This research was not conducted on behalf of or in association with any development agency or mHealth initiative; rather, our purpose was to test how social and cultural research methods can be used to anticipate opportunities and barriers to the use of consumer mobile devices to support lifelong healthy behaviours.

5.2 Problem Definition: Optimising Adherence to Therapy

Established HIV/AIDS communication strategies can focus on awareness-raising messaging campaigns in order to boost numbers of patients being tested and identified as disease-bearing. Whilst effective in attracting possible HIV+ clients to initial testing, this top-down approach to health communication is less focused upon retaining patients throughout the later phases of diagnosis and ongoing treatment to achieve suppression of viral load across the lifespan. Therefore, despite significant advances in HIV/AIDS treatment, a high percentage of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) do not maintain their programme of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and therefore do not achieve full viral load suppression. The UNAIDS Prevention Gap Report (2016) indicates that from an estimated 5.1 million people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in the Asia and Pacific region, an average of 34% of diagnosed PLWHA continue antiretroviral treatment (ART) to full viral suppression.

This suboptimal percentage of retention of PLWHA in formal treatment continues to significantly degrade the long-term effectiveness of HIV/AIDS treatment in Indonesia and throughout the region. Provinces in Indonesia with high HIV/AIDS incidence include Bali, East Java, Central Java, West Java, Jakarta, West Papua and Papua (Jiamsakul et al., 2014). High-risk groups in Indonesia include men who have sex with men (MSM), female sex workers (FSW), clients of FSW, injecting drug users (IDUs) and so-called ‘general women’ (GW) (Republic of Indonesia Ministry of Health, 2012):

-

MSM may be homosexual, bisexual or primarily heterosexual. It has been suggested that young MSM who are primarily heterosexual and cohabit with female partners may form a significant infection bridge (Walsh, 2011, p. 1861).

-

FSW. Female sex workers occupy a high-risk category for HIV transmission. An interview-based study of commercial FSW in Bali reported very low levels of safe sex education and HIV transmission reduction skills, particularly in new FSWs who grew up in village environments (Januraga, Mooney-Somers, & Ward, 2014). The same study highlights the market pressure on FSWs to have unprotected sex with clients.

-

IDUs. Unsafe injecting drug use is a major driver of both HIV and hepatitis C in the Asia region (Stone, 2015). The illegal nature of injecting drug use means that some IDUs may not disclose either drug use or HIV status when accessing health services. As a result, IDUs can ‘have low HIV testing rates and, for those living with HIV, lower access to health services and lower viral suppression rates’ compared to other PLWHA (Pierce et al., 2015).

-

GW. ‘General women’ can refer to the heterosexual partners of MSM or male IDUs. This group may remain undiagnosed until symptoms develop or a child is lost due to HIV/AIDS; delayed detection in GW also impacts mother-to-child transmission as well as transmission to other partners (Rahmalia et al., 2015). A 2012 study forecasted that the GW group will become the second biggest category for new HIV infection in Indonesia after MSM (Republic of Indonesia Ministry of Health, 2012).

5.3 Grassroots Opportunities

In this context, the critical role of community health workers (CHWs) in supporting PLWHA to adhere to antiretroviral therapy across the lifespan) is clear. We uphold the discussion by Tariq and Durrani in Chap. 2 of this book regarding the critical function provided by community health workers (CHWs) within public health delivery (see also Perry, Zulliger, & Rogers, 2014). Our interest here is in exploring CHWs’ everyday uses of mobile phones, and in considering such uses’ promise for extending health services to marginalised groups.

A number of researchers have proffered assessments of mobile tools’ potential to enhance the work of CHWs. According to Giachandani, for example:

…besides their increasingly ubiquitous use in patients’ and caregivers’ day-to-day lives, mobile and interactive real-time tools can enable community health workers to support their dual role as providers of health care to individuals and communities, as well as sentinels for emerging health hazards and needs (Gianchandani, 2011, p. 125).

To support this view, a thematic review of simple mobile-based communication tactics in low/middle-income countries found that one-way SMS or voice medication notifications and clinical appointment reminders were already a common application (Kallander et al., 2013). Such reminders can be sent directly to patients or to an intermediary such as a CHW, especially when a patient may not have mobile access or may not wish their identity to be known by formal health services—see, for example, DeRenzi et al. (2012). Two-way communication via mobile can include SMS requests for health advice or information on clinic locations (Déglise, Suggs, & Odermatt, 2012). Since the recovery regimes for both HIV/AIDS and injecting drug use (IDU) require the precise regulation of time to enable both daily medication and daily abstinence, these kinds of simple reminder services would be expected to provide a useful service to patients. Dutta-Bergman (2004) differentiates between active (requiring user motivation) and passive (minimal user effort required) channels of communication and even a simple mobile handset can offer access to passive support such as daily SMS reminders sent by a health facility or CHW.

With specific regard to HIV/AIDS retention, there is some evidence to indicate that adherence to ART can be improved through regular and early counselling that proceeds in tandem with mobile social networking. A monitoring study of 12 clinical sites from Hong Kong, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines identified multiple influences on suboptimal adherence within the first 2 years of ART including mode of HIV exposure, ART regimen, time on ART and frequency of adherence measurement (Jiamsakul et al., 2014). The authors propose that ‘a greater emphasis on more frequent adherence counselling immediately following ART initiation and through the first six months may be valuable in promoting treatment and programme retention’ (ibid.). In some contexts, CHWs can provide counselling services as either an accompaniment or an alternative to an outpatient facility. With regard to marginalised PLWHA, CHWs and community-based organisations can be particularly effective since social support from friends and family may be scarce due to the stigmatised nature of professional sex work or injecting drug use (Weaver et al., 2014). For instance, CHWs can give initial pre- or post-HIV test counselling and an introduction to formal health services as required; they can also provide longer term regular counselling to PLWHA in order to build and maintain adherence to ART over time (Jiamsakul et al., 2014). Alongside formal counselling services, in better-connected regions, mobile social networking can contribute to ‘communities of support’ understood as ‘formally constituted, public structures such as support groups, self-help groups and mutual help groups’ (Barnes, 2012). The importance of online communities of support to those with chronic illness with low access to resources is increasingly recognised (e.g. Davis & Calitz, 2016).

5.4 Grassroots Challenges

Despite the promise mobile technologies hold for extending outreach work for PLWHA, significant challenges remain. Previous studies demonstrate that mobile channels of health support are not necessarily adopted by PLWHA. From the patient’s perspective, the receipt of regular SMS reminders—e.g. to encourage adherence to a daily ART regime or to support abstinence—may not be appropriate due to the perceived risk of ‘discovery’ by family, colleagues or others who may not know that the client is a PLWHA. For instance, a pilot test of mobile phone reminders (voice and text) to support adherence by 139 adult HIV patients at a Bangladesh clinic found that although 90% of participants reported the medication reminders as useful and did not perceive an intrusion of privacy, 87% reported a preference for a voice call over SMS (Sidney et al., 2012). These participants were largely urban-based and educated to at least a secondary level. A qualitative study of PLWHA participants conducted in Lima, Peru (n = 26) expressed positive perception of SMS reminders but with the significant proviso that the text replaced sensitive words such as HIV or antiretroviral with codewords or codephrases (Curioso et al., 2009). Furthermore, we should not assume that any SMS sent will actually be received: a 2014 interview-based US study (Gonzales, Ems, & Suri, 2014) argued that the multiple barriers presented by out-of-credit mobiles or by users who swap numbers regularly not only challenge simple communication strategies such as voice calls from health staff or automated SMS, they can also serve to further isolate the out-of-credit user from their wider online/mobile/social communities of support.

Neither should we assume that mobile-enabled systems will be embraced by all CHWs. A mixed-methods formative evaluation of an mHealth intervention at an HIV/AIDS clinic in Uganda found that some CHWs believed that mobile technology would threaten their jobs; others were uncomfortable with the confidentiality issues raised by having patient data on their mobile device, such as taking a patient’s photo (Chang et al., 2013, p. 877). Also in Uganda, a study of a text message campaign that disseminated and measured HIV/AIDS knowledge in at-risk populations found that the design of the campaign ‘failed to address several informational, economic, and sociocultural vulnerabilities’ and that community-based research should be included as part of future campaign planning (Chib, Wilkin, & Hoefman, 2013, p. 30).

Even where support services such as outpatient visitation and/or CHW support are available, continuation of ART over the life course should not be expected. An interview-based study of PLWHA in Bali who also use drugs found suboptimal adherence behaviours in the participants despite comparatively good access to health services. Amongst other factors, participants cited ART side-effects, low viral load and apparent good health or ‘knowing friends who had stopped treatment and were doing fine’ as reasons for suspending or stopping ART (McNally, Mantara, Wulandari, & Lubis, 2013).

5.5 Aim, Sites of Investigation

The aim of this study was to test how social and cultural research methods can be used to anticipate opportunities and barriers to the use of consumer mobile devices by community health workers in the area of HIV/AIDS. Specifically, we investigated how CHWs have integrated mobile phones and social networking into their daily professional and personal routine—not as a result of a formal mHealth development initiative but rather through personal choice, organisational preference and/or in response to localised factors.

A qualitative study was conducted with participants from two community health NGOs in Indonesia. Participants were recruited from (a) the Yayasan Kesehatan Bali NGO in Denpasar, Bali and (b) the Ballata HIV/AIDS drop-in centre in Makassar, South Sulawesi. These two regional sites offered some useful comparisons for an exploratory study of this nature. First, both organisations were accessible to the research team and shared a similar core mission to mediate between local health departments and hard-to-reach, high-risk segments such as commercial sex workers and intravenous drug users living with HIV/AIDS. Second, the sites offered interesting contrasts: Denpasar (pop. ≈ 459 k at 2016Footnote 1) is the capital city of Bali with a majority Hindu population. Denpasar is a rapidly developing business and tourism hub which attracts domestic and international tourists. Makassar (pop. ≈ 1.4 m at 2013Footnote 2) is the capital city of the South Sulawesi region with a majority Muslim population. The city is a major commercial port.

Established in April 1999, Yayasan Kesehatan Bali (the Bali Health Foundation) is an NGO known more widely by the abbreviation Yakeba. Focusing on drug and alcohol addiction in and around Denpasar, Yakeba employs a team of field-based CHWs to

-

Support drug users and people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA),

-

Provide information about drug abuse and HIV/AIDS to clients and

-

Facilitate client referrals to health services (Yayasan Kesehatan Bali, 2014).

Ballata is a drop-in centre in the city of Makassar, South Sulawesi where CHWs and outreach workers specialising in HIV/AIDS can share stories and information with colleagues. Ballata was established in 2012 as a provincial government initiative but today is maintained by a group of PLWHA and IDUs with various organisational affiliations.

5.6 Approach, Methods

Ten Yakeba community health workers or administrators were recruited (F4:M6) between 25 and 47 years old. Nine Ballata members were recruited (F3:M6) between 27 and 43 years old. Recruitment at both sites was facilitated a Bali-based NGO dealing with public information and journalism advocacy and with experience in HIV/IDU health communication. Regular use of mobile phones and social networks as part of the participants’ work with PLWHA was a requirement for participation in the study. Two workshops were conducted with each group in the second half of 2013 at different locations in Denpasar and Makassar, respectively. All activities were conducted in Indonesian language. Research assistants took notes of interviews and group discussions. Where appropriate audio recordings were also made, parts of which were later transcribed. Where necessary some data were translated into English language for further analysis. Participants were offered a modest remuneration for their time contribution to the project.

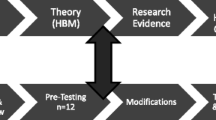

The research design was constructed within the theoretical framework of the ‘communicative ecology’ which draws upon the fields of social anthropology, human–computer interaction and communication for development. The communicative ecology framework considers media usage at the site of investigation ‘at both individual and community level as part of a complex media environment that is socially and culturally framed’ (Hearn & Foth, 2007). Therefore, in order to understand any single aspect of a media technology intervention at a particular site, the communicative ecologies researcher needs to understand how the intervention fits into wider contexts. Furthermore, the research design had to be responsive to the range of issues arising from an investigation of this nature including client identity and data confidentiality and negative attitudes towards PLWHA from some elements of the wider community. In order to construct a research environment in which participants would be able to feel comfortable and to speak freely, three data collection methods were employed (informed partly by a study of HIV CHWs in Haiti, see Mukherjee & Eustache, 2007):

-

Individual questionnaire on individual participants’ use of their mobile phone, e.g. network, tariff, place most used (e.g. home, work and on the move) and principal activities performed (e.g. music, SMS, voice, gaming and SNS).

-

Group survey on communication within the organisation (one interviewer per five participants). The survey consisted of four multiple choice questions on preferred formal versus informal sources of health management information (e.g. healthcare professional, social services, immediate family, friends, etc.) and four open questions on levels of trust in health information sources; self-perception of behaviour change due to health information sources; preference for health communication via phone, email or face-to-face; and the role of the mobile device in personal health management.

-

Communicative ecology (CE) mapping (one interviewer per two participants). Informed by sociological work on communication and social order (Altheide, 1994), CE mapping is a conceptual rather than a cartographic method which connects a respondent’s self-reported activity over a ‘normal’ 24-h to their communication behaviours during the same period, as part of an in-depth interview.

A second focus group was conducted 2 weeks later with the same group of participants. Participants were divided into two groups with one facilitator assigned to each group. Three main themes were explored during the workshops in order to generate further qualitative data on how each organisation has been impacted by mobile systems as well as the increasingly fuzzy border between personal and professional use of the mobile:

-

Impact of mobiles on work: do CHWs find that having a mobile phone with them all day is generally a help—due to constant contact with colleagues, friends and family—or a hindrance—due to the stress of being always contactable?

-

Mobile versus in-person interaction: to what extent can CHWs perform their work using mobile or other devices to communicate and share information? Do CHWs prefer dealing with challenging situations or clients in-person, by email or otherwise?

-

Personal connectivity: to what extent do the mobile phone and/or social networks facilitate contact with friends and family? Maintaining personal connectivity can be an important support for those in counselling roles, especially since most of the participants from the Yakeba organisation were themselves in recovery and/or living with HIV/AIDS.

A manual thematic analysis was conducted on all data collected from the interviews, focus groups and communicative ecology maps in order to generate results. Four main thematic categories used for analysis are discussed below:

-

Device and network usage,

-

Impact of the mobile phone on work tasks,

-

Preference for mobile phone versus in-person interaction and

-

Personal connectivity with friends, family.

5.7 Results: Denpasar Site

5.7.1 Usage

Based on the individual questionnaire, seven out of ten of the Yakeba participants reported the mobile as their most important personal communication technology, and all participants considered the mobile to be of ‘high importance’ in their lives. Analysis of the communicative ecology maps indicated different levels of device usage:

-

Five participants reported that all their working hours and much of their waking hours were spent engaging with their mobile device for both professional and personal interaction. Two participants reported a feeling of confusion (galau/bingung) if they were unable to connect.

-

Two participants reported the mobile device as their main daily communication technology interaction, which was restricted to a limited daily duration, i.e. each morning to confirm meetings and schedules.

-

Two participants reported laptop usage as their main communication activity, one reported television.

The communicative ecology mapping exercise indicated that television was the second most-used medium, with all Yakeba participants reporting TV watching as a common night-time activity. Some reported consuming news and current affairs content whilst others had the television on as ‘wallpaper’. Social media were widely used for work and/or personal networking including Facebook, Twitter, Foursquare and WhatsApp. Based on the responses from participants to the individual questionnaire on mobile device/social networking activities:

-

Average spend on mobile credit was reported to be between IDR 100,000 and 350,000 per month.

-

Eight participants used a BlackBerry (in some cases alongside a second Nokia handset).

-

Eight participants used BBM (BlackBerry Messenger) as their main communication portal.

-

Five participants checked their mobile immediately upon waking. Two participants checked their device in the early morning after domestic chores.

5.7.2 Impact of Mobiles on Work

The core philosophy of the Yakeba organisation is that people who have lived with drug or alcohol problems or who are HIV+ are best equipped to help clients with a similar condition or experience (Yayasan Kesehatan Bali, 2014). Therefore, a number of the Yakeba participants in this study were PLWHA and/or IDU, and a key feature of the NGO’s culture was that co-workers should provide a mutual community of support to their colleagues. As a result, one of the most significant daily interactions reported by Yakeba participants was the daily in-person Narcotics Anonymous morning meeting at the main office. The daily message of support generated by this meeting was sent via SMS to staff unable to attend.

With respect to interaction between CHWs and clients, boundary issues were reported by some participants since some clients would contact Yakeba CHWs at antisocial hours, perhaps to ask for needles or for medication. Yakeba’s Director had asked the CHW team to erect some boundaries in order to moderate such calls, e.g. that clients should warn CHWs when their ART supply was getting low, rather than waiting until their medication had run out to get in contact.

During the fieldwork for this project, the RIM BlackBerry was still the desired mobile device for much of the Indonesian market (Lee, 2014; Safitri, 2011) and partly as a consequence, the most popular network within the Yakeba organisation was the BlackBerry Messenger (BBM) app (although the BlackBerry is now being supplanted across Indonesia by the Android OS). The individual questionnaire flagged a gender-based and/or urban/regional digital divide within the participants: two female participants came from a regional area of Bali and had no BlackBerry, and hence no engagement with the various Yakeba activities facilitated by BBM—since BBM was only available on BlackBerry phones at this time.

5.7.3 Mobile Versus In-Person Interaction

A range of questions in the group survey responses on whether CHWs preferred to interact with clients via mobile phone (or other platforms) or via face-to-face meetings. An influential factor was the type of client with whom CHWs worked with. One CHW working with PLWHA stressed the importance of face-to-face meetings in order to accurately assess the health status of clients:

I communicate most often face-to face, on a home visit. For example, some clients say on SMS that they are OK, but when you visit them, some cannot get up because of poor health. So we make sure of their condition by visiting them. (Translated response to group survey, 08 Sep 2013).

This was confirmed another CHW who stressed that phone communication with institutions, health departments or contractors was often inappropriate:

To get to know a client’s condition, I have to physically visit him… Furthermore, institutional meetings must be done face-to-face. (Translated response to group survey, 08 Sep 2013).

Those who did not work with PLWHA felt less need for face-to-face client interaction. One respondent pointed out that although BBM was a popular platform for internal communication, it did not extend to clients:

To communicate with clients, I use the telephone and text messages the most. I rarely use BBM. Nowadays, clients rarely have or use BB. The intensity of my meeting with clients is also high. (Translated response to group survey, 08 Sep 2013).

The communicative ecology mapping exercise revealed that some core organisational interactions remained resolutely in-person. For example, the weekly team planning meeting remained a largely analogue affair: the agenda was circulated on paper, key weekly activities were written up on the whiteboard and staff members took notes on paper. Once the main aims and objectives for the week were established, individual staff members set up their appointments on BlackBerry or other available phones. In this way, the core business of Yakeba’s CHWs and administrators remained similar to the pre-mobile system, i.e. in-person team briefings, paper-based agendae and notebooks and an emphasis on face-to-face interaction. New client data were captured on paper forms and then input onto spreadsheets or databases by a data entry operator employed by the NGO. Some client information such as contact details and a personal photo were maintained on the personal phones of CHWs; Yakeba’s Director reported that the organisation had not received any complaints from clients about personal information storage despite the sensitivity of this information.

5.7.4 Personal Connectivity

Focus groups revealed that as well as communication with clients and colleagues, the mobile provided a social and emotional link to those Yakeba staff with family in other parts of Bali or Indonesia. When asked in the group survey about the impact of mobiles on their lives, some participants underlined the importance of their mobile phone and their main social network in connecting them to their family before discussing the use of the device for work. According to one team leader:

I use [BBM] to keep in contact with my family – many of my relatives live far away – but also to coordinate my team at work, to communicate with peers and with stakeholders at other agencies. (Translated response to group survey, 08 Sep 2013).

One CHW also spoke of the multiple ways in which she used BBM:

It’s really useful for communicating with family, keeping in contact with clients and peers. I also use BBM to communicate with workers at the community health service. (Translated response to group survey, 08 Sep 2013).

During focus group discussion, two participants described their phone as their second wife/husband, suggesting a significant emotional dependence. Other social networks used for work and personal communication included Facebook, Twitter, WeChat and WhatsApp. Interaction with mailing lists was popular with one team leader:

…other than participating in the office group on BB, I also join in many other groups too… a high school group; my friends; my relatives; my extended family. For networking, I use WhatsApp, it has a networking group of Indonesian friends of drugs victims… I have joined many mailing lists. They can be accessed via my mobile phone. So, in one mailing list owned by PKNI [a national network of drug user organisations] many teenagers with HIV have joined in. A social-orientated NGO from Australia often posts comments there. (Translated response to group survey, 08 Sep 2013).

5.8 Results: Makassar Site

Nine participants from the Ballata organisation based in the city of Makassar were recruited for this study. Their occupations were as follows: field coordinator, project manager, PLWHA buddy (×3), community organiser and NGO activist (×3).

5.8.1 Usage

Ballata participants reported the expenditure of between 100 and 300 K rupiah a month on phone credit which was similar to the figures reported by the Yakeba participants. All participants reported that their employer did not pay for or subsidise their phone or online connection costs, although in some cases an employer did provide a laptop for work tasks. Two participants owned multiple handsets. Most of the participants used a low-cost access plan with cheap voice calls and in two cases, separate plans were used across different handsets to source the best price deals.

5.8.2 Impact of Mobiles on Work

One of the primary objectives of the Ballata organisation is to provide a support centre in Makassar where PLWHA can seek vital information from ‘trusted friends’ about the highly stigmatised HIV/AIDS condition. As a result, one important theme to emerge from the group survey was the question of which sources of health information were accessed and/or trusted by the Ballata participants. One group of participants pointed to friends, colleagues and family as the most trusted sources, whilst doctors and healthcare workers were mentioned by all participants as sources. Due in part to a reportedly less-than-reliable mobile network availability, online desktops and laptops were used more frequently than mobiles for this kind of access. The reliability of online sources was an area of debate:

- Facilitator::

-

[Scripted question and response options]. Where do you get information about health?

- NGO activist::

-

I get it from the internet, friends, NGOs, community health centre and lastly from the doctor.

- Comm organiser::

-

I get it from friends, internet, NGOs, community health centre and the doctor

- NGO activist::

-

Friends, NGOs, internet, the doctor and the community health centre.

- Outreach worker::

-

I get info from friends, then look on the internet, from NGOs, from the community health centre and the doctor.

- Facilitator::

-

[Scripted question]. Which of these sources do you most trust?

- Comm organiser::

-

Friends. Why friends? Because I think they are best able to keep a secret.

- NGO activist::

-

Internet.

- Facilitator::

-

Why?

- NGO activist::

-

I don’t have a reason, I just trust it.

- Activist::

-

I trust colleagues, because they understand a lot of the information. Yep, friends and colleagues. I am with my friends every day. All the information that comes to me, I verify it on the internet, but that doesn’t mean I get information from the internet, and swallow it whole. I just use the internet information to compare with what friends have said.

- NGO activist::

-

I believe the internet. If you get information off people, you have to factor in human error.

- Activist::

-

Do you really think there is no room for human error on the internet?! Who do you think puts this stuff on the internet?! Sounds like you really believe the internet, then!

- NGO activist::

-

Yes, I believe the internet.

(Translated responses to group survey, 08 Dec 2013).

This exchange raises a number of important issues regarding health information literacy which are further explored in the Discussion (Sect. 4.8).

5.8.3 Mobile Versus In-Person Interaction

Both the focus group discussions and communicative ecology mapping indicated a common behaviour across participants:

-

Voice calls were preferred for work conversations, e.g. with external organisations and stakeholders.

-

SMS was used for personal communication but rarely for work.

-

No social network or platform was used for inter-organisation communication.

-

Face-to-face meetings with clients were preferred; in some cases, these meets were supported by voice calls to remind clients to take medication.

One Ballata CHW working with IDU clients suggested that face-to-face meetings were essential, since some IDUs did not trust the motivations of CHWs:

Developing a relationship of trust with IDUs takes a lot of time, because most of them assume that outreach workers are keen to move them into rehab, and many of them don’t want to go to rehab. Many of them are scared of outreach workers for that reason. So cultivating a good relationship with them is a long process. (Translated interview comment by male community health worker, 08 Dec 2013).

For example, the Ballata project manager used email to coordinate frequent meetings with health department officials, whereas one of the NGO activists who conducted paralegal work frequently browsed via mobile in order to keep up-to-date with developments in criminal law related to drug use. No comparable use of a shared social network—comparable to Yakeba’s used of BBM—was evident amongst the Ballata members, who worked for different organisations and had varying uses of mobile phones and Internet. Facebook was used by some participants for work contacts living in different regions including national bodies such as the National Drug Users’ Union. The less-than-reliable network reported by the Makassar-based participants may be responsible in part for the lower use of mobile social networks when compared to the Denpasar-based Yakeba participants.

5.8.4 Personal Connectivity

Responses to the group survey revealed some complexity in personal device management. The BlackBerry remained a preferred device for some participants, in some cases operating alongside other brands such as Nokia and Samsung. One of the NGO activists reported a particularly complex device strategy in which the more familiar strategy of separating family and work contacts was approached rather differently:

- Facilitator::

-

[Scripted question]. What apps do you have on your phone?

- NGO activist::

-

WhatsApp, Line, WeChat. Initially I had a Fleksi phone [i.e. CDMA handset]. Then I bought a BlackBerry and Android. Now I use all three. Fleksi for my mum and my boss, because I am close to them and often call them. The BlackBerry for friends who have a BlackBerry. For my girlfriend and for work friends, I use the BlackBerry.

- Facilitator::

-

Of those three devices, which is most important to you?

- NGO activist::

-

The Android. It has lots of apps.

(Translated response to group survey, 08 Dec 2013).

The PLWHA buddy also reported a multi-device strategy with a preference for social networking over voice and SMS:

- PLWHA buddy::

-

I use two phones, a Nokia and a BlackBerry. The BlackBerry is for friends and groups and I have eight BBM groups. I also use the BlackBerry for browsing, Twitter and WeChat.

- Facilitator::

-

Which do you use most?

- PLWHA buddy::

-

BBM. The Nokia is for voice calls and SMS.

(Translated response to group survey, 08 Dec 2013).

Another NGO activist reported a less ‘complicated’ device strategy which forewent mobile networking in preference for laptop access:

- NGO activist::

-

I only have one phone. I’m the kind of person who doesn’t want to be complicated. I don’t want to use a BlackBerry and I only have a BlackBerry by coincidence. I used to have a Nokia but if they get wet, Nokias are hopeless. BlackBerrys are good, strong. I have had a Samsung for two years

- Facilitator::

-

Can it access the internet?

- NGO activist::

-

It can.

- Facilitator::

-

What have you installed on it?

- NGO activist::

-

Facebook and Twitter. But I don’t use them. I access Facebook from my laptop. I just get notifications on my phone, so I can control my phone use.

(Translated response to group survey, 08 Dec 2013).

As indicated by the response from the NGO activist, the use of multiple devices by these CHWs cannot be understood using a simplistic segmentation such as the use of separate devices or social networks for family versus work. Furthermore, a multiple device environment also challenges the implementation of mHealth systems for CHW use. In principle, we could use a mobile web browser to facilitate compatibility across multiple mobile phones, but this could cause problems when the mobile cannot connect in low-/no-network reception areas which can be expected in the field. In contrast, the use of front-end apps might make offline work easier, but it may also require the implementation and maintenance of apps across multiple platforms. Assuming that some PLWHA clients also maintain multiple phones, the challenges multiply for even a simple system such as automated SMS medication reminders—how can CHWs and health authorities be sure that reminders are being sent to the correct device, that the device is in credit and is being monitored by the user?

5.9 Conclusion

Thematic analysis of the qualitative data collected from participants at both sites confirmed the ability of CHWs in both the Yakeba and Ballata organisations to mediate between health departments and hard-to-reach, high-risk segments such as commercial sex workers and intravenous drug users living with HIV/AIDS. Furthermore, the analysis demonstrated that the mobile phone was an important tool for CHWs at both organisations in terms of inter-organisation communication, supplementing or supplanting face-to-face interaction with clients, and maintaining important personal connections with friends and family. It has been suggested more generally that the possible application of mobile phones, networks and apps to community-level mHealth work ‘has intuitive appeal’ (Braun, Catalani, Wimbush, & Israelski, 2013). However, this appeal must be weighed against some of the barriers to informal mHealth adoption by CHWs revealed at the two sites of investigation, to which other comparable organisations may be susceptible. Building upon the thematic analysis, the barriers discussed in this section are as follows:

-

Health infrastructure,

-

FSW client mobility and

-

Information literacy.

5.9.1 Health Infrastructure

A number of policy reports have highlighted the need for the integration of mHealth solutions within a holistic healthcare delivery strategy (e.g. Lemaire, 2011). With regard to CHWs, it has been suggested that:

End-to-end patient care systems and point-of-care support for health workers are needed whereby mHealth applications are interoperable and integrated with provider systems linking the most remote community health worker with the most appropriate sources of information when and where it is needed (Mechael et al., 2010, p. 5).

As a result, the effectiveness of the CHW is necessarily curtailed when the availability of a wider system of end-to-end care and point-of-care support is lacking, and there is only a limited amount that mHealth systems can achieve in such an environment. This barrier was illustrated well by the two contrasting sites of investigation selected for this study. The city of Denpasar is distinctive in that it hosts one of Indonesia’s few drop-in HIV clinics for female sex workers, a very high-risk group. This clinic was also one of the few sites in the country where free access to ART medication for PLWHA was guaranteed. Access to medication and specialised clinics are two very important factors to longer term adherence to ART and from our analysis of data collected from the Ballata participants, it was inferred that access to ART medication was more limited for PLWHA in Makassar—which in turn limited the effectiveness of Ballata CHWs in keeping their clients on medication when compared to their Denpasar-based peers. In principle, ART medication has been free of charge for all Indonesians since 2006 (Jakarta Post, 2014). In practice, PLWHA have sometimes had to pay for ART due to insufficient supply of medication—and possibly some issues of graft in healthcare delivery (Buehler, 2008). Note that since the introduction of a new national healthcare scheme in 2013, there is evidence that the supply problems are being addressed: a 2015 estimate indicates 253 hospitals across 33 provinces where PLWHA can access free ART medication (Yayasan Spiritia, 2015).

5.9.2 FSW Client Mobility

CHWs are generally understood to be a member of the community in which they work (Kane et al., 2016) and by inference, it is understood that the CHW usually supports a geographically bounded population. Therefore, the modus operandi of all local health service providers—including CHWs—is challenged by a large transitory population which does not remain in one geographic location long enough to be able to connect with local health services. Although not specifically questioned on this point, the mobility of clients of HIV-infected female sex workers (FSWs) was raised by some Yakeba participants as a critical barrier to health service provision for HIV/AIDS. At the time of fieldwork, the Yakeba NGO had approximately 300 HIV and 90 IDU clients registered. However, the organisation’s client numbers fluctuated monthly often due to infrastructure projects which can attract construction workers from other parts of Indonesia, in turn boosting demand for FSWs. For example, the Nusa Dua toll road project and the new Denpasar airport terminal were estimated by Yakeba to have brought 13,000 construction workers from Java into Bali between January and October 2013 as part of infrastructure spending catalysed by Bali’s hosting of the 2013 Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit. It is extremely challenging for any regional NGO or health department to interact long-term with these highly transitory groups who may contract and spread the HIV virus to FSWs at their temporary work site and to wives and/or partners when they return to their home province. One can argue that the application of informal mHealth support could play a valuable role within this scenario via automated medication notifications or keep a transitory worker in touch with his/her own communities of support via social network. However, this would require the worker to be connected with mHealth providers in their home province, which may not be available in rural and regional areas. Based on group survey data from the Yakeba participants, other factors impacting client mobility include:

-

Phased closure of recognised prostitution areas in Surabaya which increased the numbers of sex workers to Bali.

-

Regular weekend movement of elite sex workers from Bandung and Jakarta to Bali in order to service clients.

-

Increased MSM (men who have sex with men) activity during holidays.

5.9.3 Information Literacy

A primary function of the CHWs at both the Yakeba and Ballata organisations was to offer support and reliable health information to PLWHA from marginalised groups who might not have access to authoritative health sources either physical or online. For example, a qualitative study of newcomer FSWs working in Bali found a lack of knowledge and self-efficacy about HIV prevention due to low levels of sexual education, as well as limited opportunities to interact with positive social networks around HIV prevention (Januraga et al., 2014). Such lack of health information literacy is certainly not unique to HIV/AIDS—for example, see work on the potential of mobile dissemination of information on sexual reproductive health in Indonesia (Gerdts, Hudaya, & Belusa, 2014). The provision of reliable health information as part of wider education and awareness was identified as a key objective for a range of mHealth initiatives in developing countries (Chigona, Nyemba, & Metfula, 2012). However, the multiple issues that can arise when untrained users access unreliable online health sources are well known and despite the potential harm that inaccurate or misunderstood online health information can play in patient safety, many formal online health-related information accreditation schemes remain underused (Wong, Yan, Margel, & Fleshner, 2013). The pros and cons of online health information within the context of community health work were evident in the discussion between Ballata members (reported in the Results section). Although multiple sources of health information were accessed by most—e.g. Internet, friends, NGOs, community health centre and doctor—the participants differed on what they considered their most trusted source. One reported friends, one reported friends and colleagues, and one reported an unwavering belief in the Internet despite criticism from a colleague.

Information literacy issues were apparent at the Yakeba organisation in terms of client data collection and processing. As stated, new client data were captured on a range of paper-based forms since different funders of the NGO had different information reporting requirements. For instance, data required by the health department were manually input into a spreadsheet and then uploaded to a department website by a data entry operator employed specifically for this purpose by Yakeba. Although the Yakeba leadership was aware that this process could be substantially accelerated via off-the-shelf or customised mobile apps, their funding bodies preferred paper-based systems, and the NGO itself did not have sufficient funding or expertise to establish mobile data solutions. Furthermore, protocols for securing extremely confidential client data remained fledgling. When considering how even simple mHealth systems could support PLWHA to adhere to daily ART programmes, it is evident that systematised and confidential data protocols are required to generate and follow-up automated medication notifications or meeting reminders. Neither organisation studied was close to this level of information literacy. Two Yakeba coordinators stated that they saw no reason to move away from paper-based client data collection.

5.10 Conclusion

The aim of this qualitative study was to test how social and cultural research methods can be used to anticipate opportunities and barriers to the use of consumer mobile devices by CHWs working in the area HIV/AIDS. Through the application of the communicative ecologies framework and qualitative methods, we found no bottom-up impetus from either NGO for the introduction of a formal mHealth system to support client interactions. Although mobile phones were used extensively at both sites of investigation to support work-related functions, the clear preference for CHWs at both the Yakeba and Ballata NGOs was to meet PLWHA clients face-to-face in order to build trust and conduct an unobtrusive visual health check. There was limited use of basic SMS medication reminders by some CHWs but no organisation-wide automated systems to support ongoing adherence to antiretroviral therapy were in place. Client data collection was conducted using paper-based systems to ensure compatibility with local government and/or funding body administrative systems. Some team leaders at the Yakeba organisation saw little reason to replace the paper-based process with a more automated system which would require substantial reformulation of and retraining in data protocols not just by the NGO itself but also by local health departments and funding bodies. As community health services may often operate on a minimal budget, it was unlikely that any such reformulation and retraining would be available over the medium-term. Furthermore, the priority placed on face-to-face client meetings by CHWs at both the Yakeba and Ballata organisations would continue to physically limit the number of clients that each CHW could handle as part of their daily caseload, thereby limiting the possible efficiency gains via mHealth automation that a policymaker or funding body might seek when considering how to increase the financial sustainability of ART adherence and retention programmes.

One of the objectives of this book is to recognise that mHealth initiatives cannot be executed as technical programmes in a vacuum, ignoring the complex social and cultural contexts in which they are implemented. Our study supports this view to some extent: by using a communicative ecologies framework to guide this study, we found that CHWs at both sites of investigation saw no significant opportunities for an mHealth intervention to improve their existing work processes or to more closely support client interaction. This is not to say that no such scope exists: rather, the significant organisational process changes that would be required by NGOs as well as local, regional and national health departments in order to introduce and maintain consistent mobile-friendly data collection, and security protocols would require resources that are not available at this time.

5.10.1 Limitations

This qualitative study was based upon two site-specific localised contexts which necessarily prevent any generalisation of the findings to a regional or national platform. Rather, this study should be considered alongside larger-scale quantitative reports such as the eHealth surveys conducted by the WHO Global Observatory for eHealth (WHO, 2016). However, our findings do confirm that multiple soft organisational and cultural barriers to adoption can be expected by any media technology-oriented project (Chang et al., 2013) and as a consequence, the adoption of formal or informal mHealth tools, methods or systems by CHWs and/or smaller scale NGOs should not be assumed by policymakers or system designers.

Notes

- 1.

http://bali.bps.go.id/linkTableDinamis/view/id/20 accessed 20 July 2016.

- 2.

http://sulsel.bps.go.id/linkTabelStatis/view/id/115 accessed 20 July 2016.

References

Altheide, D. L. (1994). An Ecology of Communication. Sociological Quarterly, 35(4), 665–683.

Barnes, J. (2012). Communities of support. Paper presented at the IST-Africa 2012 Conference Proceedings. www.IST-Africa.org/Conference2012.

Braun, R., Catalani, C., Wimbush, J., & Israelski, D. (2013). Community health workers and mobile technology: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS ONE, 8(6), e65772.

Buehler, M. (2008). No positive news. Inside Indonesia, 94.

Chang, L. W., Njie-Carr, V., Kalenge, S., Kelly, J. F., Bollinger, R. C., & Alamo-Talisuna, S. (2013). Perceptions and acceptability of mHealth interventions for improving patient care at a community-based HIV/AIDS clinic in Uganda: a mixed methods study. AIDS Care: Psychological and Socio-medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 25(7), 874–880.

Chib, A., Wilkin, H., & Hoefman, B. (2013). Vulnerabilities in mHealth implementation: A Ugandan HIV/AIDS SMS campaign. Global Health Promotion, 20(1), 26–32.

Chigona, W., Nyemba, M., & Metfula, A. (2012). A review on mHealth research in developing countries. Journal of Community Informatics, 9(2).

Curioso, W. H., Quistberg, D. A., Cabello, R., Gozzer, E., Garcia, P. J., Holmes, K. K. et al. (2009). “It’s time for your life”: How should we remind patients to take medicines using short text messages? Paper presented at the AMIA 2009 Symposium Proceedings.

Davis, D. Z., & Calitz, W. (2016). Finding healthcare support in online communities: An exploration of the evolution and efficacy of virtual support groups. In Y. Sivan (Ed.), Handbook on 3D3C platforms: Applications and tools for three dimensional systems for community, creation and commerce (pp. 475–486). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Déglise, C., Suggs, L. S., & Odermatt, P. (2012). Short Message Service (SMS) applications for disease prevention in developing countries. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(1), e3.

DeRenzi, B., Findlater, L., Payne, J., Birnbaum, B., Mangilima, J., Parikh, T., … Lesh, N. (2012). Improving community health worker performance through automated SMS. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

Dutta-Bergman, M. J. (2004). Developing a profile of consumer intention to seek out additional health information beyond the doctor: Demographic, communicative, and psychographic factors. Health Communication, 17, 1–16.

Gerdts, C., Hudaya, I., & Belusa, E. (2014). MHealth and safe-abortion: Improving information about and access to safe misoprostol abortions in Indonesia. Paper presented at the 142nd American Public Health Association (APHA) Annual Meeting and Exposition 2014, New Orleans, USA. https://apha.confex.com/apha/142am/webprogram/Paper297938.html.

Gianchandani, E. P. (2011). Toward smarter health and well-being: an implicit role for networking and information technology. Journal of Information Technology, 26, 120–128.

Gonzales, A. L., Ems, L., & Suri, V. R. (2014). Cell phone disconnection disrupts access to healthcare and health resources: A technology maintenance perspective. New Media & Society, 1–17.

Hearn, G. N., & Foth, M. (2007). Communicative ecologies. Electronic Journal of Communication, 17, 1–2.

Jakarta Post. (2014, August 19). Domestically manufactured ARV medication warmly welcomed. Retrieved from http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2014/08/19/domestically-manufactured-arv-medication-warmly-welcomed.html.

Januraga, P. P., Mooney-Somers, J., & Ward, P. R. (2014). Newcomers in a hazardous environment: A qualitative inquiry into sex worker vulnerability to HIV in Bali, Indonesia. BMC Public Health, 14, 832.

Jiamsakul, A., Kumarasamy, N., Ditangco, R., Li, P. C. K., Phanuphak, P., Sirisanthana, T., et al. (2014). Factors associated with suboptimal adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Asia. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 17(1), 18911.

Kallander, K., Tibenderana, J. K., Akpogheneta, O. J., Strachan, D. L., Hill, Z., ten Asbroek, A. H., et al. (2013). Mobile health (mHealth) approaches and lessons for increased performance and retention of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries: A review. J Med Internet Res, 15(1), e17.

Kane, S., Koka, M., Ormel, H., Otiso, L., Sidat, M., Namakhoma, I., et al. (2016). Limits and opportunities to community health worker empowerment: A multi-country comparative study. Social Science and Medicine, 164, 27–34.

Lee, T. (2014, October 02). BlackBerry losing popularity in Indonesia. übergizmo. Retrieved from http://www.ubergizmo.com/2014/02/blackberry-losing-popularity-in-indonesia/.

Lemaire, J. (2011). Scaling up mobile health: Elements necessary for the successful scale up of mHealth in developing countries. Retrieved from https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/ADA_mHealthWhitePaper.pdf.

McNally, S., Mantara, I. M. A., Wulandari, L. P. L., & Lubis, D. (2013). Stopping ARV treatment in Bali, Indonesia. Poster presented at the 11th International Congress on AIDS in Asia and the Pacific, Bangkok.

Mechael, P. N., Batavia, H., Kaonga, N., Searle, S., Kwan, A., Goldberger, A., … Ossman, J. (2010). Barriers and gaps affecting mHealth in low and middle income countries: Policy white paper. Retrieved from http://www.comminit.com/ict-4-development/content/barriers-and-gaps-affecting-mhealth-low-and-middle-income-countries-policy-white-paper.

Mukherjee, J. S., & Eustache, F. E. (2007). Community health workers as a cornerstone for integrating HIV and primary healthcare. AIDS Care, 19, 73–82.

Perry, H. B., Zulliger, R., & Rogers, M. M. (2014). Community health workers in low-, middle-, and high-income countries: An overview of their history, recent evolution, and current effectiveness. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 399–421.

Pierce, R. D., Hegle, J., Sabin, K., Agustian, E., Johnston, L. G., Mills, et al. (2015). Strategic information is everyone’s business: Perspectives from an international stakeholder meeting to enhance strategic information data along the HIV cascade for people who inject drugs. Harm Reduction Journal, 12(41).

Rahmalia, A., Wisaksana, R., Meijerink, H., Indrati, A. R., Alisjahbana, B., Roeleveld, N., et al. (2015). Women with HIV in Indonesia: Are they bridging a concentrated epidemic to the wider community? BMC Research Notes, 8, 757.

Republic of Indonesia Ministry of Health. (2012). Estimates & Projection of HIV/AIDS 2011–2016. Retrieved from http://www.ino.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/HIV-AIDS_and_sexually_transmitted_infections_Estimates_and_Projection_HIV_AIDS_ENGLISH.pdf.

Safitri, D. (2011). Why is Indonesia so in love with the Blackberry? BBC News. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/direct/indonesia/9508138.stm.

Sidney, K., Antony, J., Rodrigues, R., Arumugam, K., Krishnamurthy, S., D’Souza, G., et al. (2012). Supporting patient adherence to antiretrovirals using mobile phone reminders: Patient responses from South India. AIDS Care, 24(5), 612–617.

Stone, K. A. (2015). Reviewing harm reduction for people who inject drugs in Asia: The necessity for growth. Harm Reduction Journal, 12, 32.

UNAIDS. (2016). Prevention gap report. Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2016-prevention-gap-report_en.pdf.

Walsh, C. S. (2011). Mobile and online HIV/AIDS outreach and prevention on social networks, mobile phones and MP3 players for marginalised populations. Paper presented at the Global Learn Asia Pacific.

Weaver, E. R. N., Pane, M., Wandra, T., Windiyaningsih, C., Herlina, & Samaan, G. (2014). Factors that influence adherence to antiretroviral treatment in an urban population, Jakarta, Indonesia PLoS ONE, 9(9).

WHO. (2016). Atlas of eHealth country profiles 2015: The use of eHealth in support of universal health coverage. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/goe/publications/atlas_2015/en/.

Wong, L.-M., Yan, H., Margel, D., & Fleshner, N. E. (2013). Urologists in cyberspace: A review of the quality of health information from American urologists’ websites using three validated tools. Canadian Urological Association Journal, 7(100–6).

Yayasan Kesehatan Bali. (2014). Yakeba—profile. Retrieved from yakeba.org/?page_id = 111.

Yayasan Spiritia. (2015). Daftar Rumah Sakit Rujukan AIDS di Indonesia. Retrieved from http://spiritia.or.id/rsrujukan.php#SumateraUtara.

Acknowledgements

We thank both the Yakeba and Ballata organisations for their full and open participation in this study. This research was funded by the Australian Research Council Discovery Project scheme Mobile Indonesians, DP130102990. Initial findings were presented both to the International Communication Association regional conference, Brisbane 01–03 October 2014 and the Workshop on Mobiles and Social Media in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, University of Sydney, 12–13 November 2015. We thank the reviewers who have provided feedback to earlier versions of this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2018 Asian Development Bank

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Watkins, J., Baulch, E. (2018). Identifying Grassroots Opportunities and Barriers to mHealth Design for HIV/AIDS Using a Communicative Ecologies Framework. In: Baulch, E., Watkins, J., Tariq, A. (eds) mHealth Innovation in Asia. Mobile Communication in Asia: Local Insights, Global Implications. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1251-2_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1251-2_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-024-1250-5

Online ISBN: 978-94-024-1251-2

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)