Abstract

Versified mathematical algorithms and problems make their appearance in China around the end of the Song dynasty (eleventh century) and are widely spread among the sources of the Ming (1368–1644) and the Qing (1644–1911) dynasties.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

A list of Chinese dynasties and their respective dates is given in the appendix.

- 2.

Rote learning or learning by rote is learning things mechanically by repeating them without thinking about them or trying to understand them.

- 3.

Elman (2001, 268).

- 4.

Lee (2000, 623).

- 5.

Also called Trimetrical Classic, see Giles (1900, iv): “a hornbook for boys”.

- 6.

- 7.

Citation by Gui Yougang (1507–1571) according to McLaren (2005, 167–168).

- 8.

Full literacy is sometimes called vocality, meaning the ability to express oneself in writing.

- 9.

See Elman (2001, 261–270).

- 10.

In Chinese age reckoning newborns start at 1 year old, and according to the lunar calendar the person’s age is incremented each passing of a New Year.

- 11.

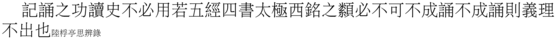

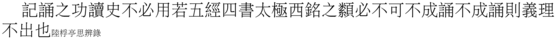

Cited from Lu Shiyi’s Notes on Reflections and Disputations according to Zhou (1895, 38A), a compilation of citations concerning the reading of books:

.

- 12.

Elman (2001, 262–263).

- 13.

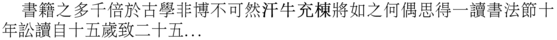

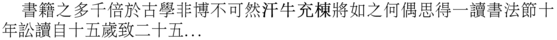

The Chinese saying “enough books to make the ox carrying them sweat” (han niu chong dong

) refers to an immense number of books. See Zhou (1895, 38A–40B):

.

- 14.

McLaren (2005, 167–168).

- 15.

Fishmongers for example used the Seven-words-a-line song of fish names (Yuming qi yan ge

. See Wang (1994, 55).

- 16.

The thirteenth-century book on divination Yuanhai ziping

by Xu Sheng

, for example, gives a seven- and a five-syllable-a-line verse for respectively memorizing the sequence of the 12 earthly branches and the 10 heavenly stems, as well as fortune-telling verses. See Wang (1994, 50–51).

- 17.

- 18.

The now still extant Ten Books of Mathematical Classics (Suanjing shi shu

) were especially compiled to serve as textbooks in a specific sequence. See Siu and Volkov (1999).

- 19.

See Lee (2000, 517–525).

- 20.

See Li (1954–1955) for a bibliography of extant and lost Ming dynasty texts.

- 21.

Cheng (1990, 991) even refers to one book which explicitly indicates versified content in the title, the now lost Sanyuan hua ling ge

.

- 22.

The texts were flawed by a mixture of simplified and variant writings of characters.

- 23.

- 24.

The expression ‘nine numbers’ probably refers to the multiplication table up to nine times nine. See for example the Outline in Zhu (1839, 1127), where this multiplication table is referred to as the ‘Method of the Nine Numbers’ (

).

- 25.

The Chinese term for heaps refers to an accumulation of discrete objects like grains, in a certain geometric shape, whereas ‘volumes’ refers to a continuous geometric solid.

- 26.

The terminology here refers to the method of double false position.

- 27.

This is necessary to solve systems of linear equations.

- 28.

Liu Hui’s commentary (dated 263) to the algorithm for square root extraction in the Nine Chapters makes use of colors to refer to the geometric entities in a square corresponding to the terms in the algorithm. See Chemla and Guo (2004, 322–329). For a further discussion of the algorithm of square root extraction in its versified form see Sect. 7.3.1.6.

- 29.

Denoting a set of multiplication jingles for x ⋅y, where x ≤ y and x, y ≤ 9.

- 30.

Technical term for division by one-digit numbers x ÷ y, where x, y ≤ 9 and x ≥ y.

- 31.

Mathematically meaning, that in division of 60 by 8, one obtains 7 and a rest of 4, when multiplying 6 by 8 one obtains 48. The smaller characters here reflect the fact that this phrase is typeset as a commentary in the original text.

- 32.

See Cheng (1990, juan 1: 9B).

- 33.

Cheng (1990, 800).

- 34.

- 35.

Translated from the preface to Wang (2008, xxiii).

- 36.

See the Table of contents (Wang 1524, xxxiii–xxxv). The tunes were Shuixian zi

(Ondine), Xijiang yue

(Moon of the Western River), Luomei feng

(Wind from Falling Plums), Shanpo yang

(Sheep on a Precipice), Chao tianzi

(Son of Heaven), Qing jiang yin

(Clear River, a Prelude), Zui taiping

(Drunk in a Peaceful Time), Hong xiuxie

(The Red Embroidered Shoes), Wu ye’r

(Leaves of Chinese Parasol Tree), Yan er luo

(Falling Swan), Zhegu tian

(A Partridge in the Sky), Pu tian le

(The World being Overjoyed).

- 37.

Cheng (1990, 888–890).

- 38.

The name of the tune stems from a Tang dynasty poem by Li Bai

, The Ruin of the Gu-Su Palace

.

- 39.

The patterns required a certain sequence of level/even tones (ping

) and oblique/non-level/uneven tones (ze

). The tune here follows the pattern:

where the middle tone (zhong

) in brackets signifies an optional choice between even and uneven tone.

- 40.

A number of variant and simplified character forms rarely used in formal writing before the Ming are included in the printed version I have consulted. I have adopted their nowadays standard form in my transcription.

- 41.

This is the case for example for the two homophone measure words for bottles: zhi is either printed as

or as

. There are also two different expressions used for a heap (or pile): a variant form of duo

and dui

.

- 42.

Author of a now lost book from 1424, entitled Entirely Understandable Mathematical Methods from the Nine Chapters (Jiu zhang tongming suanfa

). See Li (1954–1955).

- 43.

Reference to the Great Compendium of the Yongle Reign-Period (1403–1422) (Yongle dadian

).

- 44.

At least such is the case in the commented 1836 edition by Luo Shilin, which is the earliest printed edition preserved. There is an earlier manuscript version, dated 1819 in the National Library of China (Ancient Rare Books Section N ∘ 16000), and another manuscript in the National Palace Museum in Taipei, which was copied during the Jiaqing reign (1796–1820), but I have not had a chance to revisit these for this article. See Brard (1999, Chap. 4, n. 19).

- 45.

- 46.

See Cheng (1990, juan 16: 935).

- 47.

See Problem 9.6 in Chemla and Guo (2004, 711).

- 48.

Cf. the situation in medicine as described by Leung (2003, 132):

Yang highly praised the work [the Yijing xiaoxue

(Primary Study on Medicine), an important medical introductory textbook written in 1388], as its rhymes and verses written to facilitate memorization by beginners were based on classics.

- 49.

Cf. Leung (2003, 141):

Although the verse form could not express the exact composition of the various recipes, it provided the principles of the combination of various drugs in recipes for different purposes.

- 50.

- 51.

In modern terminology, the problem can be transcribed as a system of simultaneous linear congruence equations:

- 52.

- 53.

- 54.

Translated from Cheng (1990, juan 5: 430). Libbrecht (1973, 291–292) translates the passage as follows: Three septuagenarians in the same family is exceptional.

Twenty-one branches of plum-blossom from 5 trees.

seven brides in ideal union precisely the middle of the month.

Subtract 105 and you get it.

Volkov (2002, 401) says the text “may approximately be rendered as follows: Three men walking together, [then] seventy are rare/dispersed (?);

Five trees, 21 branches of plum-blossoms;

Seventh [month’s] gathering is in the middle of the month [=15th day];

Subtract 105 and then [you] can know [the answer].”

- 55.

The goal of these techniques, referred to as ‘the opening of the square’, is to eliminate successively surfaces of a square, having at the outset a surface equivalent to the number one wants to extract the square root of. The algorithm comes to an end, when one has exhausted the entire surface of the square. For a detailed discussion of the algorithm for square root extraction in the Nine Chapters and Liu Hui’s commentary to it, see Chemla (1994).

- 56.

Cheng (1990, juan 6: 1A (445)).

- 57.

Voir (Cheng 1990, juan 6: 1A–1B (445–446)).

- 58.

I will discuss such kind of jingles with further examples in Sect. 7.3.1.10.

- 59.

This sentence is printed in smaller characters. This usually marks a commentary or a later addition to the original edition.

- 60.

- 61.

Translated from Cheng (1990, juan 17: 3b (p. 946)).

- 62.

- 63.

See the appendix to Brard (2010), which gives the variant rhymes from four Jianyang imprints.

- 64.

See Xu (1573).

- 65.

Illustration from Yu (1599).

- 66.

Division by estimation of the quotient, originally using three lines on the calculation surface in counting rod calculation.

- 67.

Translated from Zhu (1839, 1127).

- 68.

See Cheng (1990, juan 2: 8b (78)).

- 69.

Ibid. juan 2: 9a (79).

- 70.

- 71.

A book by the same author, Yang Hui, the Xiangjie jiuzhang suanfa

, written in 1261.

- 72.

Elman (2001, 268).

- 73.

See also Lowry (2005, 93):

The bowdlerized written forms suggest that, though perhaps not the most discerning, the reading public for such materials had sufficient familiarity with the verses (as well as recognizing a number of characters) to make sense of variant forms used by printers or copyists.

- 74.

Whether variations were bound to regional dialects as to maintain the rhyme patterns, still needs to be explored.

- 75.

Illustration from Cheng (1882), originally published in 1592.

References

Brard, Andrea. 1999. Re-Kreation eines mathematischen Konzeptes im chinesischen Diskurs: Reihen vom 1. bis zum 19. Jahrhundert. Boethius, vol. 42. Stuttgart: Steiner Verlag.

Brard, Andrea. 2010. Knowledge and practice of mathematics in late-ming daily-life encyclopedias. In Looking at it from Asia. The processes that shaped the sources of history of science. Boston studies of philosophy of science, ed. Florence Bretelle-Establet et al. Dordrecht: Kluver.

Chemla, Karine. 1994. Similarities between Chinese and Arabic mathematical documents (I): Root extraction. Arabic Sciences and Philosophy 4: 207266.

Chemla, Karine, and Guo, Shuchun. 2004. Les Neuf Chapitres sur les procdures mathmatiques. Paris: Dunod.

Cheng, Dawei

(1533–1606). 1882. Zengbu Suanfa tongzong daquan

(1533–1606). 1882. Zengbu Suanfa tongzong daquan

(Complemented collection of the Unified Lineage of Mathematical Methods).

(Complemented collection of the Unified Lineage of Mathematical Methods).  Taishantang edn.

Taishantang edn.Cheng, Dawei

(1533–1606). 1990. Suanfa tongzong jiaoshi

(1533–1606). 1990. Suanfa tongzong jiaoshi

(Annoted edition of the Unified Lineage of Mathematical Methods). Hefei: Anhui jiaoyu chubanshe

(Annoted edition of the Unified Lineage of Mathematical Methods). Hefei: Anhui jiaoyu chubanshe

. Reprint of the 1716 edition.

. Reprint of the 1716 edition.Elman, Benjamin A. 2001. A cultural history of civil examinations in late imperial China, Reprint edn. Taibei: SMC Publishing Co. Originally published Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Friedsam, Manfred. 2003. L’enseignement des mathmatiques sous les Song et Yuan. In Éducation et instruction en Chine, vol. II. Les formations spcialises, ed. C. Despeux, and C. Nguyen Tri, 49–68. Bibliothque de l’INALCO, vol. 5. Paris – Louvain: Editions Peeters.

Giles, Herbert A. (trans.) 1900. Elementary Chinese. San Tzu Ching (

). Shanghai: Messrs. Kelly & Walsh. Reprinted in Peking, China 1940.

). Shanghai: Messrs. Kelly & Walsh. Reprinted in Peking, China 1940.Guo, Shuchun

et al. (eds). 1993. Zhongguo kexue jishu dianji tonghui. Shuxue juan

et al. (eds). 1993. Zhongguo kexue jishu dianji tonghui. Shuxue juan

, 5 vols. Zhengzhou: Henan jiaoyu chubanshe

, 5 vols. Zhengzhou: Henan jiaoyu chubanshe  .

.Honda, Seiichi

. 1994.

. 1994.  (“Children’s mathematical education during the Song, Yuan and Ming dynasties”). Kyūshū Daigaku Tōyōshi ronshū

(“Children’s mathematical education during the Song, Yuan and Ming dynasties”). Kyūshū Daigaku Tōyōshi ronshū

(Oriental studies), 37–72.

(Oriental studies), 37–72.Lam, Lay Yong, and Tian Se Ang. 2004. Fleeting footsteps: Tracing the conception of arithmetic and algebra in ancient China, Revised edn. Singapore: World Scientific.

Lee, H.C. Thomas. 2000. Education in traditional China. A history. Handbook of oriental studies, vol. 13. Leiden/Boston/Kln: Brill.

Leung, Angela Ki Che. 2003. Medical instruction and popularization in ming-qing China. Late Imperial China 24(1): 130152.

Li, Yan

. 1954–1955. Mingdai de suanxue shuzhi

. 1954–1955. Mingdai de suanxue shuzhi  (“Bibliography of mathematical works of the Ming Dynasty”). In Zhong suan shi luncong

(“Bibliography of mathematical works of the Ming Dynasty”). In Zhong suan shi luncong

. (Collected essays on Chinese mathematics), vol. 2. 86–102. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe. Reprinted from Tushuguan xue jikan

. (Collected essays on Chinese mathematics), vol. 2. 86–102. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe. Reprinted from Tushuguan xue jikan

(Library science quarterly) 1.4 (1926), pp. 667–682.

(Library science quarterly) 1.4 (1926), pp. 667–682.Libbrecht, Ulrich. 1973. Chinese mathematics in the thirteenth century. The Shu-shu chiu-chang of Ch’in Chiu-shao. Cambridge: MIT.

Lowry, Kathryn A. 2005. The Tapestry of popular songs in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century China: Reading, imitation, and desire. Sinica Leidensia series, vol. 67. Leiden/New York: Brill.

Martzloff, Jean-Claude. 1997. A history of Chinese mathematics. New York: Springer.

McLaren, Anne E. 2005. Constructing new reading publics. In Printing & book culture in late imperial China, ed. Cynthia J. Brokaw and Kai-Wing Chow, 152–183. Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Qian, Baocong

. 1963. Suanjing shi shu

. 1963. Suanjing shi shu

(Ten Books of Mathematical Classics). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju

(Ten Books of Mathematical Classics). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju  .

.Sakade, Yoshinobu

Ogawa, Yōichi

Ogawa, Yōichi  , and Sakai, Tadao

, and Sakai, Tadao  (eds). 2000. Chūgoku nichiyō ruisho shūsei

(eds). 2000. Chūgoku nichiyō ruisho shūsei

. Tokyo: Kyūko shoin

. Tokyo: Kyūko shoin  .

.Siu, Man-Keung, and Alexei Volkov. 1999. Official curriculum in traditional Chinese mathematics: How did candidates pass the examinations? Historia Scientiarum 9(1): 87–99.

Volkov, Alexei. 2002. On the origins of the Toan phap dai thanh (great compendium of mathematical methods). In From China to Paris: 2000 years transmission of mathematical ideas. Boethius, vol. 46, ed. Yvonne Dold-Samplonius, 369–410. Stuttgrat: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Wang, Wensu

. 1524. Xinji tongzheng gujin suanxue baojian

. 1524. Xinji tongzheng gujin suanxue baojian

(Mathematical mirror of old and new mathematical learning, newly collected and corrected). Manuscript copy of 41 juan from Beijing Library. Reprint in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 2: 337–971).

(Mathematical mirror of old and new mathematical learning, newly collected and corrected). Manuscript copy of 41 juan from Beijing Library. Reprint in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 2: 337–971).Wang, Ermin

. 1994. Zhongguo chuantong jisong zhi xue yu shiyun koujue

. 1994. Zhongguo chuantong jisong zhi xue yu shiyun koujue

(“Chinese traditional recitation methods and arts of rhyming”). Zhongyang yanjiuyuan Jindai shi yanjiusuo jikan

(“Chinese traditional recitation methods and arts of rhyming”). Zhongyang yanjiuyuan Jindai shi yanjiusuo jikan

(Journal of the Institute of Modern Chinese History at the Academia Sinica), 23: 31–64.

(Journal of the Institute of Modern Chinese History at the Academia Sinica), 23: 31–64.Wang, Wensu

. 2008. Suanxue baojian jiaozhu

. 2008. Suanxue baojian jiaozhu

(Critical edition of the Precious mirror of mathematical learning). Beijing: Kexue chubanshe

(Critical edition of the Precious mirror of mathematical learning). Beijing: Kexue chubanshe  .

.Wu, Jing

. fl. 1450. Jiu zhang suanfa bilei daquan

. fl. 1450. Jiu zhang suanfa bilei daquan

(Great compendium of analogical categories to the Nine Chapters of Mathematical Methods). Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 2: 1–333).

(Great compendium of analogical categories to the Nine Chapters of Mathematical Methods). Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 2: 1–333).Xu, Xinlu

. 1573. Panzhu suanfa

. 1573. Panzhu suanfa

(Methods for Calculating on an Abacus). Xiong tainan

(Methods for Calculating on an Abacus). Xiong tainan  edn. Complete title:

edn. Complete title:  (Newly engraved and corrected edition of the Method of Calculating on an Abacus , with verses for memorization transmitted secretly through family, for the use of scholars and commoners. Preserved in Japan, Naikau bunko,

(Newly engraved and corrected edition of the Method of Calculating on an Abacus , with verses for memorization transmitted secretly through family, for the use of scholars and commoners. Preserved in Japan, Naikau bunko,  56

56  5

5  . Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 2: 1143–1164).

. Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 2: 1143–1164).Yang, Hui

. 1275. Xugu zhaiqi suanfa

. 1275. Xugu zhaiqi suanfa

(Selection of Strange Mathematical Methods in Continuation of Antiquity). Manuscript edn. Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 1: 1095–1117).

(Selection of Strange Mathematical Methods in Continuation of Antiquity). Manuscript edn. Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 1: 1095–1117).Yang, Hui

. 1842. Chengchu tongbian suanbao

. 1842. Chengchu tongbian suanbao  (“Mathematical treasure of variations on multiplication and division”). In Yang Hui suanfa

(“Mathematical treasure of variations on multiplication and division”). In Yang Hui suanfa

,

,  yijiatang congshu edn.

yijiatang congshu edn.Yu, Xiangdou

(ed). 1599. Santai wanyong zhengzong

(ed). 1599. Santai wanyong zhengzong

(complete title: Santai’s orthodox instructions for myriad uses for the convenient perusal of all the people in the world, newly engraved Xinke tianxia simin bianlan Santai wanyong zhengzong

(complete title: Santai’s orthodox instructions for myriad uses for the convenient perusal of all the people in the world, newly engraved Xinke tianxia simin bianlan Santai wanyong zhengzong

). Housed in Tōkyō Daigaku Tōyō Bunka Kenkyūjo Niida Bunko

). Housed in Tōkyō Daigaku Tōyō Bunka Kenkyūjo Niida Bunko  (Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, Niida Collection). Reproduced in (Sakade et al. 2000, vols. 3–5).

(Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, Niida Collection). Reproduced in (Sakade et al. 2000, vols. 3–5).Zhang, Zhigong

. 1962. Chuantong yuwen jiaoyu chutan

. 1962. Chuantong yuwen jiaoyu chutan

(Preliminary inquiry into traditional language education). Shanghai: Shanghai jiaoyu chubanshe

(Preliminary inquiry into traditional language education). Shanghai: Shanghai jiaoyu chubanshe  .

.Zhu, Shijie

. 1839. Suanxue qimeng

. 1839. Suanxue qimeng

(Introduction to Mathematical Learning).

(Introduction to Mathematical Learning).  Yangzhou edn. Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 1: 1123–1200).

Yangzhou edn. Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 1: 1123–1200).Zhou, Yongnian

. 1895. Xianzheng dushu jue

. 1895. Xianzheng dushu jue

(Recipes of Effective Reading by Ancient Wisdom). Guiyang: Yan Xiu

(Recipes of Effective Reading by Ancient Wisdom). Guiyang: Yan Xiu  .

.Zhou, Mi

. 1969. Zhiyatang zachao

. 1969. Zhiyatang zachao

(Random Jottings from the Hall for Pursuit of Elegance). Biji xubian

(Random Jottings from the Hall for Pursuit of Elegance). Biji xubian  ; 31. Taibei: Guangwen shuju

; 31. Taibei: Guangwen shuju  .

.Zhu, Shijie

and Guo, Shuchun

and Guo, Shuchun  (trans.) and Chen, Zaixin

(trans.) and Chen, Zaixin  (Engl. trans.). 2006. Siyuan yujian

(Engl. trans.). 2006. Siyuan yujian

(Jade Mirror of Four Unknowns). Shenyang: Liaoning jiaoyu chubanshe

(Jade Mirror of Four Unknowns). Shenyang: Liaoning jiaoyu chubanshe  .

.Zhu, Shijie

and Luo, Shilin

and Luo, Shilin  (comm.). 1937. Siyuan yujian xicao

(comm.). 1937. Siyuan yujian xicao

(Detailed Explanations of the Jade Mirror of Four Unknowns). Wanyou wenku

(Detailed Explanations of the Jade Mirror of Four Unknowns). Wanyou wenku  , vol. 2–700. Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan

, vol. 2–700. Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan  . Originally published 1836.

. Originally published 1836.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bréard, A. (2014). On the Transmission of Mathematical Knowledge in Versified Form in China. In: Bernard, A., Proust, C. (eds) Scientific Sources and Teaching Contexts Throughout History: Problems and Perspectives. Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science, vol 301. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5122-4_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5122-4_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-5121-7

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-5122-4

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawHistory (R0)

(1533–1606). 1882. Zengbu Suanfa tongzong daquan

(1533–1606). 1882. Zengbu Suanfa tongzong daquan

(Complemented collection of the Unified Lineage of Mathematical Methods).

(Complemented collection of the Unified Lineage of Mathematical Methods).  Taishantang edn.

Taishantang edn. (1533–1606). 1990. Suanfa tongzong jiaoshi

(1533–1606). 1990. Suanfa tongzong jiaoshi

(Annoted edition of the Unified Lineage of Mathematical Methods). Hefei: Anhui jiaoyu chubanshe

(Annoted edition of the Unified Lineage of Mathematical Methods). Hefei: Anhui jiaoyu chubanshe

. Reprint of the 1716 edition.

. Reprint of the 1716 edition. ). Shanghai: Messrs. Kelly & Walsh. Reprinted in Peking, China 1940.

). Shanghai: Messrs. Kelly & Walsh. Reprinted in Peking, China 1940. et al. (eds). 1993. Zhongguo kexue jishu dianji tonghui. Shuxue juan

et al. (eds). 1993. Zhongguo kexue jishu dianji tonghui. Shuxue juan

, 5 vols. Zhengzhou: Henan jiaoyu chubanshe

, 5 vols. Zhengzhou: Henan jiaoyu chubanshe  .

. . 1994.

. 1994.  (“Children’s mathematical education during the Song, Yuan and Ming dynasties”). Kyūshū Daigaku Tōyōshi ronshū

(“Children’s mathematical education during the Song, Yuan and Ming dynasties”). Kyūshū Daigaku Tōyōshi ronshū

(Oriental studies), 37–72.

(Oriental studies), 37–72. . 1954–1955. Mingdai de suanxue shuzhi

. 1954–1955. Mingdai de suanxue shuzhi  (“Bibliography of mathematical works of the Ming Dynasty”). In Zhong suan shi luncong

(“Bibliography of mathematical works of the Ming Dynasty”). In Zhong suan shi luncong

. (Collected essays on Chinese mathematics), vol. 2. 86–102. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe. Reprinted from Tushuguan xue jikan

. (Collected essays on Chinese mathematics), vol. 2. 86–102. Beijing: Kexue chubanshe. Reprinted from Tushuguan xue jikan

(Library science quarterly) 1.4 (1926), pp. 667–682.

(Library science quarterly) 1.4 (1926), pp. 667–682. . 1963. Suanjing shi shu

. 1963. Suanjing shi shu

(Ten Books of Mathematical Classics). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju

(Ten Books of Mathematical Classics). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju  .

. Ogawa, Yōichi

Ogawa, Yōichi  , and Sakai, Tadao

, and Sakai, Tadao  (eds). 2000. Chūgoku nichiyō ruisho shūsei

(eds). 2000. Chūgoku nichiyō ruisho shūsei

. Tokyo: Kyūko shoin

. Tokyo: Kyūko shoin  .

. . 1524. Xinji tongzheng gujin suanxue baojian

. 1524. Xinji tongzheng gujin suanxue baojian

(Mathematical mirror of old and new mathematical learning, newly collected and corrected). Manuscript copy of 41 juan from Beijing Library. Reprint in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 2: 337–971).

(Mathematical mirror of old and new mathematical learning, newly collected and corrected). Manuscript copy of 41 juan from Beijing Library. Reprint in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 2: 337–971). . 1994. Zhongguo chuantong jisong zhi xue yu shiyun koujue

. 1994. Zhongguo chuantong jisong zhi xue yu shiyun koujue

(“Chinese traditional recitation methods and arts of rhyming”). Zhongyang yanjiuyuan Jindai shi yanjiusuo jikan

(“Chinese traditional recitation methods and arts of rhyming”). Zhongyang yanjiuyuan Jindai shi yanjiusuo jikan

(Journal of the Institute of Modern Chinese History at the Academia Sinica), 23: 31–64.

(Journal of the Institute of Modern Chinese History at the Academia Sinica), 23: 31–64. . 2008. Suanxue baojian jiaozhu

. 2008. Suanxue baojian jiaozhu

(Critical edition of the Precious mirror of mathematical learning). Beijing: Kexue chubanshe

(Critical edition of the Precious mirror of mathematical learning). Beijing: Kexue chubanshe  .

. . fl. 1450. Jiu zhang suanfa bilei daquan

. fl. 1450. Jiu zhang suanfa bilei daquan

(Great compendium of analogical categories to the Nine Chapters of Mathematical Methods). Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 2: 1–333).

(Great compendium of analogical categories to the Nine Chapters of Mathematical Methods). Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 2: 1–333). . 1573. Panzhu suanfa

. 1573. Panzhu suanfa

(Methods for Calculating on an Abacus). Xiong tainan

(Methods for Calculating on an Abacus). Xiong tainan  edn. Complete title:

edn. Complete title:  (Newly engraved and corrected edition of the Method of Calculating on an Abacus , with verses for memorization transmitted secretly through family, for the use of scholars and commoners. Preserved in Japan, Naikau bunko,

(Newly engraved and corrected edition of the Method of Calculating on an Abacus , with verses for memorization transmitted secretly through family, for the use of scholars and commoners. Preserved in Japan, Naikau bunko,  56

56  5

5  . Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 2: 1143–1164).

. Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 2: 1143–1164). . 1275. Xugu zhaiqi suanfa

. 1275. Xugu zhaiqi suanfa

(Selection of Strange Mathematical Methods in Continuation of Antiquity). Manuscript edn. Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 1: 1095–1117).

(Selection of Strange Mathematical Methods in Continuation of Antiquity). Manuscript edn. Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 1: 1095–1117). . 1842. Chengchu tongbian suanbao

. 1842. Chengchu tongbian suanbao  (“Mathematical treasure of variations on multiplication and division”). In Yang Hui suanfa

(“Mathematical treasure of variations on multiplication and division”). In Yang Hui suanfa

,

,  yijiatang congshu edn.

yijiatang congshu edn. (ed). 1599. Santai wanyong zhengzong

(ed). 1599. Santai wanyong zhengzong

(complete title: Santai’s orthodox instructions for myriad uses for the convenient perusal of all the people in the world, newly engraved Xinke tianxia simin bianlan Santai wanyong zhengzong

(complete title: Santai’s orthodox instructions for myriad uses for the convenient perusal of all the people in the world, newly engraved Xinke tianxia simin bianlan Santai wanyong zhengzong

). Housed in Tōkyō Daigaku Tōyō Bunka Kenkyūjo Niida Bunko

). Housed in Tōkyō Daigaku Tōyō Bunka Kenkyūjo Niida Bunko  (Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, Niida Collection). Reproduced in (Sakade et al. 2000, vols. 3–5).

(Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, Niida Collection). Reproduced in (Sakade et al. 2000, vols. 3–5). . 1962. Chuantong yuwen jiaoyu chutan

. 1962. Chuantong yuwen jiaoyu chutan

(Preliminary inquiry into traditional language education). Shanghai: Shanghai jiaoyu chubanshe

(Preliminary inquiry into traditional language education). Shanghai: Shanghai jiaoyu chubanshe  .

. . 1839. Suanxue qimeng

. 1839. Suanxue qimeng

(Introduction to Mathematical Learning).

(Introduction to Mathematical Learning).  Yangzhou edn. Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 1: 1123–1200).

Yangzhou edn. Reprinted in (Guo et al. 1993, vol. 1: 1123–1200). . 1895. Xianzheng dushu jue

. 1895. Xianzheng dushu jue

(Recipes of Effective Reading by Ancient Wisdom). Guiyang: Yan Xiu

(Recipes of Effective Reading by Ancient Wisdom). Guiyang: Yan Xiu  .

. . 1969. Zhiyatang zachao

. 1969. Zhiyatang zachao

(Random Jottings from the Hall for Pursuit of Elegance). Biji xubian

(Random Jottings from the Hall for Pursuit of Elegance). Biji xubian  ; 31. Taibei: Guangwen shuju

; 31. Taibei: Guangwen shuju  .

. and Guo, Shuchun

and Guo, Shuchun  (trans.) and Chen, Zaixin

(trans.) and Chen, Zaixin  (Engl. trans.). 2006. Siyuan yujian

(Engl. trans.). 2006. Siyuan yujian

(Jade Mirror of Four Unknowns). Shenyang: Liaoning jiaoyu chubanshe

(Jade Mirror of Four Unknowns). Shenyang: Liaoning jiaoyu chubanshe  .

. and Luo, Shilin

and Luo, Shilin  (comm.). 1937. Siyuan yujian xicao

(comm.). 1937. Siyuan yujian xicao

(Detailed Explanations of the Jade Mirror of Four Unknowns). Wanyou wenku

(Detailed Explanations of the Jade Mirror of Four Unknowns). Wanyou wenku  , vol. 2–700. Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan

, vol. 2–700. Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan  . Originally published 1836.

. Originally published 1836.