Abstract

“Beauty” is translated into Chinese as 美 (mei) and “Aesthetics” as 美学 (meixue) (literally meaning the studies of the beauty). The compound 美学 (meixue) is new in Chinese and its origin is due to translation in modern time. But indigenous in China is the word mei (beauty), which appeared as early as more than 3000 years ago. The very first question in aesthetics was probably “what is beauty?” The concept of beauty in the mind of ancient Chinese is not necessarily identical with that in the mind of modern people, but an investigation of it may be of some interest to today’s aesthetic inquiry, and, as we shall see, it already attracts attention of some scholars in the fields of both linguistics and aesthetics.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

Shuowen Jiezi (literally means “a description of simply characters and explanation of complex characters”) is a dictionary-like book which was intended to explain Chinese characters on the basis of their forms. It was compiled by Xu Shen (30–124 A.D.). This paragraph is quoted from the entry of the beauty of this book.

- 2.

Ci Yuan, (literally means “The Orgin of Words”, Beijing: The Comercial Press, 1988).

- 3.

Zhongwen Da Cidian, (literally means, “A Great Dictionary of Chinese Words”, Taibei: 1967).

- 4.

Zhu Guangqian, Letters on Beauty, (Shanghai, 1980) p. 25. Zhu published voluminous books and papers on aesthetics from 1920s to 1980s, as well as translated many important books, such as Hegel’s Aesthetics and Vico’s The New Science, into Chinese.

- 5.

Cf. Kasahara Chuji, The Aesthetic Consciousness of Ancient Chinese. Nohon Hoyu shoten 1979.

- 6.

Shell-and-bone script was the charcters used in the late Shang Dynasty. The Shang Dynasty existed from ca. the 16th century to ca. the 11th century B.C. The earliest characters on bones was written in circa 1395 B.C. (See Hu Houxuan, A Summary of the Research on the Shell-and-bone Script in Late 50 Years (The Commerse Press, 1951) p. 66. Shell-and-bone scipt, therefore, is the writing from c. 14th century to c. the 11th century B.C.

- 7.

Bronze script can be divided into inscriptions on the bronze objects of the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century–c. 11th century B.C.) and those of the Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century–221 B.C.). But what are concerned here is mainly those of the former.

- 8.

The Book of Documents was considered to be one of the oldest books in China. Some chapters of it were proved to be written in the early years of the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century B.C.). Although the authenticity of this book was questioned by Chinese scholars from the Qing Dynasty to the early this century, it is highly probable that part of this book was edited or even re-written by people in later generations. Anyway, we still have some good evidences showing that at least part the book was indeed taking shape in the early Zhou Dynasty. Xu Xusheng managed to present a remote history of China in The Legendary Ages in Ancient Chinese History Books (Chinese Science Press, 1960), in which a paper by a scientist, Zhu Kezhen was included. This paper proves the written time of The Book of Documents by means of certain astronomical evidence, which seems more convincing than barely textual analysis.

- 9.

The Book of Poetry was allegedly compiled by Confucius (551–479 B.C.). Thus it should be a collection of poems or folk songs appeared before or contemporary to Confucius.

- 10.

The Analects was allegedly written and compiled by Confucius’s students or student’s students. If this was true, the book should take shape in ca. 450 B.C.

- 11.

Yili was also allegedly compiled by Confucius, thus it should be emerged before Confucius. Liang Qichao, The Authenticity of the Ancient Books and Their Dating “the seventeen chapters available today probably came out of Confucius’s hand. The rites in Zhou Dynasty were overlaborate. Confucius sorted them out and thus made them suitable.

- 12.

Zhouli (The Rites of the Zhou) was written in the early years of the Warring States Period (475 B.C.–221 B.C.), and was revised in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.). Zhang Xincheng, A General Survey of Ancient Books of Dubious Authenticity: Zhouli is the overall scheme for establishing the country, drafted up by the Confucians who knew the law, rituals and economy in the early Warring States Period. In the early Western Han it was stored in the loyal stacks. Liu Xin saw it during the rule of Wang Mang (9–23 A.D.), and published it with his changes.

- 13.

Zhouyi (The Book of Change) roughly consists of two groups of texts. One was written before Confucius and compiled by him and was called Yijing (The Classic of Change). The other was written by Confucius or the followers of him in the Warring States Period, and was called Yizhuan (The Annotations to the Classic of Change) or Yidazhuan (The Great Annotations to the Classic of Change). Liang Qicao illustrate a more detailed picture on it in his The Authenticity of the Ancient Books and Their Dating: “We should date the drawing of Eight Trigrams to the remote past, date the coupling of two trigrams into hexagrams, Guaci (explanation of the text of the whole hexagram) and Yaoci (the explanation of the component lines) to the early Zhou Dynasty, date Tuanci (the commentary on Guaci) and Xiangci (the explanation of the abstract meaning of Guaci and Xiangci) to Confucius, date Xici (Apprended Remarks) and Wenyan (commentary on the first two hexagrams, the qian or Heaven and the kun or Earth) to the end of the Warring States Period, date Shuogua (The Remarks on Certain Trigrams) and Zagua (The Random Remarks on the Hexagrams) to the time between the Warring States Period, and the Qin and Han dynasties. [Thus we can] observe people’s mind and outlook on the world and life in different ages.”

- 14.

The Spring and Autumn Annals, which was allegedly written by Confucius. Ban Gu wrote in his “A Biography of Sima Qian” in The History of the Han Dynasty: “Confucius wrote The Spring and Autumn Annals based on The Records of the History of the Lu State.”

- 15.

Chunqiu Zuoshi Zhuan was said to have been written by Zuo Qiuming, but it is a disputing issue. It is generally considered to have been written in the early Warring State Period, and revised in the Han Dynasty.

- 16.

Guoyu was also said to have been written by Zuo Qiuming, according to the records of some ancient books, including the Records of the Historian by Sima Qian. Some modern Chinese scholars, however, believe that it was written by many historians from 400–300 B.C. Cf. Wei Juxian A Study of Guoyu.

- 17.

Gongyang Zhuan was said to have been written by Gongyang Gao in the Warring States Period.

- 18.

Guliang Zhuan, was said to have been written by Guliang Chi in the Warring States Period.

- 19.

Daodejing was allegedly written by Laozi (Lao Dan). The Records of the Historian by Sima Qian says that Confucius once asked Laozi about the rites (see the Records of the Historian, “The Biographies of Laozi, Zhuangzi, Shen Buhai, and Han Fei”) then Laozi should live contemporary to or even a little older than Confucius. However, it is still a disputed question about whether extant Daodejing was written by Laozi. Tang Lan, Hu Shi, among other famous scholars, believed that it was written by Laozi. Feng Youlan believed that it was written in the Warring States Period (Feng Youlan, The History of Chinese Philosophy). Most Chinese scholars now accepted Feng Youlan’s opinion.

- 20.

Zhuangzi was allegedly written by Zhuang Zhou (ca. 369–286 B.C.) and his followers. Thus it took shape in the Warring States period.

- 21.

Chuci (The Poetry of the Chu) was a collection of the poems by Qu Yuan (c. 340–278 B.C.) and his followers.

- 22.

The author of Zhanguoce (The Strategy of the Warring States) is unknown. Si Ku Ti Yao (Summaries of the Four Categories of Books) says that it was compiled by Liu Xiang (77?–6 B.C.) from various historical records. Luo Genze guesses that it was written by Kuai Tong, a persuasive talker in the early Han Dynasty.

- 23.

Guanzi, though traditionally attributed to Guan Zhong (?–645 B.C.), was generally believed not written by him, but by certain Legalists in the late Warring States Period.

- 24.

The Book of Mencius was allegedly written by Meng Ke (ca. 372–289 B.C.?), and there is not much disputation on this conclusion.

- 25.

Most chapters of Xunzi were written by Xun Kuang (331?–238 B.C.), except for a few by his students or followers. Liang Qichao wrote: “Xunzi is creditable on the whole. Only seven chapters such as…are probably not completely out of the hand of Xunzi. They were recorded either by Xun’s disciples or added by people in later generations.”

- 26.

Mencius: “Which among the sliced and fried meat or yangzao (a kind of fruit) is more beautiful?” Xunzi: “It is natural to human beings that their mouths like tasty food which is taken as beauty.”

- 27.

Guo Moruo, The Bronze Age: “The text of Mozi existing today is edited by people of the Han Dynasty.” Luo Genze, An Investigation of the Texts by the Pre-Qin Philosphers quoted the remarks by Ruan Diaofu: “Mozi became a book as such actually since the Han Dynasty.”

- 28.

He Yisun, Questions and Answers about the Eleven Classics: “Question: Who wrote Liji?” Answer: “Confucius made remarks. His seventy-two disciples recorded what they had heard. The Confucians in the Qin and Han period edited them into a book. Most of them are not the original remarks of Confucius. It is only someone else’s remarks under Confuscius’s name wherever it refers to Confucius’s remarks.”

- 29.

Lüshi Chunqiu is a book written by a group of scholars under Lü Buwei (?–235 B.C.), the prime minister of the Qin state.

- 30.

Han Feizi was written by Han Fei (280?–233 B.C.), an important Legalist writer. The authenticity of this book is generally creditable.

- 31.

Silk Books from Mawangdui Tombs of the Han Dynasty.

- 32.

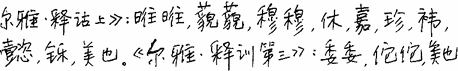

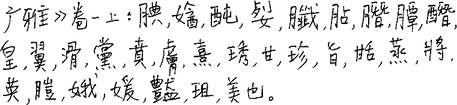

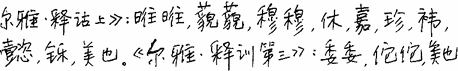

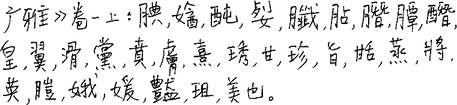

Zhang Xincheng, A General Survey of Ancient Books of Dubious Authenticity: “Erya should be a dictionary before and in the Han Dynasty. It was gradually accumulated and added, not by a single person.”

- 33.

- 34.

- 35.

Kong Kuangju, Inquisition into Shuowen should be explained as following (sheep) in its meaning and following (big) in its pronounciation. Ma Xulun, Exegesis of Suowen Jiezi: “In my mind mei must be following the meaning of (large), and following the pronounciation of yu.”

- 36.

Wang Xiantang, Collect Interpretations of Bronze Script. Kang Yin, The Souces and Development of Characters.

- 37.

Xiao Bing, “From ‘Beauty of Big Sheep’ to ‘Beauty of Sheep and Man’”, Beifang Luncong, 1980 No. 3.

- 38.

Li Zehou and Liu Gangji, Zhongguo Meixueshi (A History of Chinese Aesthetics). Vol. 1, pp. 79–82. Li Zehou, Chinese Aesthetics, pp. 2–10. Li Zehou, Four Lectures on Aesthetics, pp. 34–35. Li Zehou declares that he prefers the opinion and phrases it in rhetoric, but also acknowledges that further research is needed.

- 39.

The more recent writings on totemism, e.g. by Sigmund Freud and Claude Lévi-Strauss, seem of no direct relevance to our discussion.

- 40.

Goldenweiser, Alexander A. “Totemism: An Analytical Study”, Journal of the American Folk-Lore 23 (1910):179–293.

- 41.

J. G. Frazer, Totemism and Exogamy. Vol. II, pp. 338–339.

- 42.

Archeological evidences show that ancient Chinese began their agricultural life as early as 8000 years ago, whereas the Shang Dynasty existed only from 3500 to 3000 years ago.

- 43.

Even sheep was a sort of domestic animal.

- 44.

Cf. Chen Mengjia, A General Introduction of Bone Characters of the Yin Ruins.

- 45.

Cf. L. Lévy-Bruhl: La Mentalité primitive.

- 46.

The Book of Poetry, “Black Bird”.

- 47.

Sima Qian, Records of the Historian, “The History of the Yin (Shang)”.

- 48.

Li Zehou and Liu Gangji, A History of Chinese Aesthetics. Vol. 1, pp. 79–81. Li Zehou, Chinese Aesthetics, p. 2.

- 49.

Goodness is the translation of Chinese character 善 (shan), which also means virtue. I am going to write another paper to discuss the relation of beauty to goodness (or virtue) in ancient China.

- 50.

Cf. The so-called “great discussion of aesthetics” in China in 1950s and early1960s among Zhu Guangqian, Li Zehou, Cai Yi (1906–1991), and many other important Chinese scholars.

- 51.

Plato condemned in his dialogue Hippias Major the idea that delicious food could be beauty, too.

- 52.

That the character 美 (beauty) looks like a man wearing feathers on his head appeared earlier than that of Xiao Bing. But since it has little influence on aesthetic society, I would like to comment on it later.

- 53.

I merely plan to present specific discussions on some of his specific ideas in this paper. Li’s idea is the most influential one in China, and, even those who are challenging his ideas agree that Li’s idea is the most worthy to converse with. If this discussion has any potential theoretical meaning, that is beyond the limit of this paper. I put this issue to Prof. Li, and he considered what I was trying to do it is to add a new floor to the great mansion of human ideology. Is it possible that such a new floor provides aesthetics a new point of departure? Only a careful researching work can prove that, rather than an emotional criticism.

- 54.

Wang Xiantang, Collect Interpretations of Bronze Scripts. Kang Yin, The Sources and Development of Characters.

- 55.

This paper was written in the 1982 in Chinese and, after rejected by several journals, was published in an unimportant journal in 1988 in the end. I am delighted to know that Hanyu Dacidian (The Great Dictionary of Chinese Words, published in 1993) explains the first meaning of mei as meiguan “Good looking”, rather than “delicious” as given by Ciyuan and almost all the other important dictionaries. However, such a significant change has yet to be noticed by aestheticians in China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Foreign Language Teaching and Research Publishing Co., Ltd and Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gao, J. (2018). The Original Meaning of the Chinese Character for “Beauty”. In: Aesthetics and Art. China Academic Library. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56701-2_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56701-2_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-662-56699-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-662-56701-2

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)