Abstract

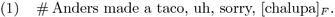

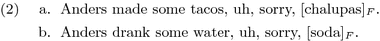

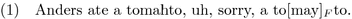

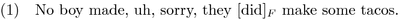

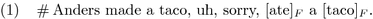

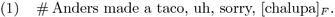

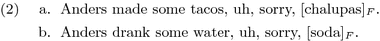

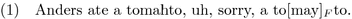

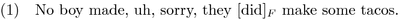

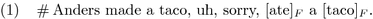

In each sentence, the speaker makes a mistake, signals that they’ve made a mistake (uh, sorry), and finally corrects their mistake.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

We expect that many of the generalizations we propose about self-corrections will extend to cross-speaker corrections, but we will not be discussing such data here.

- 2.

Note that a corresponding correction structure where the correction is a bare noun is infelicitous:

This appears to be an idiosyncratic property of singular count nouns, as the following felicitous examples demonstrate:

- 3.

Asher and Gillies (2003), Asher and Lascarides (2009), van Leusen (1994, 2004) already notice that the focus/background partition of the correction should be matched in the anchor. They ultimately propose a version of the snip & glue approach involving non-monotonic logics for Common Ground (CG) update.

- 4.

Contrastive focus can be applied to elements that differ only in terms of pronunciation (see Artstein 2004 for details), and, as expected if corrections are indeed contrast structures, such elements participate in correction structures as well:

- 5.

For example, the SDRT approach in Asher and Gillies (2003) has multiple layers of representation and multiple logics associated with these layers. Focus/background information is represented in a ‘lower’ layer and CG update is performed in a ‘higher’-level logic that non-monotonically reasons over and integrates the lower-level representations.

- 6.

Generally a plural pronoun strategy is preferred to the telescoping strategy, but telescoping is at least marginally grammatical. We’ve found in our own experimental work (not reported here) that the same is true for telescoping in corrections.

- 7.

We were first made aware of examples of this kind by Milward and Cooper (1994), though those authors do not note their theoretical significance.

- 8.

Cases like this are better with polarity reversal:

- 9.

We’ve represented the trigger uh, sorry as a lexical item contributing the crucial operator relating the correction to the anchor. This is a convenient notational choice that indicates no deep assumption of our theory; we assume that the correction operator is available independently of the way a speaker indicates that they’re making a correction, which may in principle be non-verbal.

- 10.

This step of the algorithm enforces the contrast generalization from Sect. 3.2. Note, however, that it does not rule out superfluous focus placement, as in the following infelicitous example:

In this case, the VP of the anchor is indeed a member of the focus semantic value of the correction, as taco is (trivially) of the same semantic category as itself. This problem could be solved by adding a constraint against triviality to the generation of focus alternatives, ruling out focus alternatives that include the ordinary semantic values of focus-marked elements.

- 11.

As we already indicated in Footnote 10, we assume that the multiple foci in the correction induce a suitable focus semantic value for the entire correction: assuming that ‘contrastive’ focus semantic values do not include ordinary values, we require that when multiple foci are present, any alternative that contains the ordinary value of any of the foci should be excluded from the focus value.

- 12.

To derive the correct truth conditions, we need to introduce an additional propositional dref and suitable subset relations between propositional drefs to capture the fact that anaphora from the correction to a quantifier in the anchor builds on part of the content contributed by the anchor. The subset relations \(p'_1\sqsubseteq p_1\) and \(p_2\sqsubseteq p_1\) need to preserve the full dependency structure associated with the worlds in \(p_1\). That is, for any \(p_1\)-world that we retain in the subsets \(p'_1\) or \(p_2\), we need to retain the full range of \(u_1\)-entities associated with that world.

References

Artstein, R.: Focus below the word level. Nat. Lang. Semant. 12, 1–22 (2004)

Asher, N., Lascarides, A.: Agreement, disputes and commitments in dialogue. J. Semant. 26, 109–158 (2009)

Asher, N., Gillies, A.: Common ground, corrections, and coordination. Argumentation 17, 481–512 (2003)

van den Berg, M.: The dynamics of nominal anaphora. Dissertation, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam (1996)

Brasoveanu, A.: Structured nominal and modal reference. Dissertation, Rutgers University (2007)

Clark, H.H., Tree, J.E.F.: Using uh and um in spontaneous speaking. Cognition 84(1), 73–111 (2002). doi:10.1016/S0010-0277(02)00017-3

Farkas, D.F., Bruce, K.B.: On reacting to assertions and polar questions. J. Semant. 27, 81–118 (2010)

Ferreira, F., Lau, E., Bailey, K.: Disfluencies, language comprehension, and tree adjoining grammars. Cogn. Sci. 28, 721–749 (2004)

Ginzburg, J., Fernández, R., David, S.: Disfluencies as intra-utterance dialogue moves. Semant. Pragmat. 7, 64 (2014)

Groenendijk, J., Stokhof, M.: Dynamic predicate logic. Linguist. Philos. 14(1), 39–100 (1991)

Heeman, P., Allen, J.: Speech repairs, intonational phrases and discourse markers: modeling speaker’ utterances in spoken dialogue. Comput. Linguist. 25(4), 527–571 (1999)

Hough, J., Purver, M.: Processing self-repairs in an incremental type-theoretic dialogue system. In: Proceedings of the 16th SemDial Workshop on the Semantics and Pragmatics of Dialogue (SeineDial), Paris, pp. 136–144 (2012). http://www.eecs.qmul.ac.uk/~mpurver/papers/hough-purver12semdial.pdf

van Leusen, N.: The interpretation of corrections. In: Bosch, P., van der Sandt, R. (eds.) Proceedings of the Conference on Focus and Natural Language Processing, vol. 3, pp. 1–13. IBM Working paper 7, TR-80.94-007. IBM Deutschland GmhB (1994)

van Leusen, N.: Compatibility in context: a diagnosis of correction. J. Semant. 21, 415–441 (2004)

Levelt, W.: Monitoring and self-repair in speech. Cognition 14, 41–104 (1983)

Merchant, J.: Sluicing, Islands, and the Theory of Ellipsis. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2001)

Milward, D., Cooper, R.: Applications, theory, and relationship to dynamic semantics. In: The 15th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING 1994), pp. 748–754. COLING 1994 Organizing Comm., Kyoto Japan (1994)

Muskens, R.: Combining Montague semantics and discourse representation. Linguist. Philos. 19(2), 143–186 (1996)

Nouwen, R.: Dynamic aspects of quantification. Dissertation, UIL-OTS, Utrecht University (2003)

Purver, M.: The theory and use of clarification requests in dialogue. Dissertation, King’s College, University of London (2004). http://www.dcs.qmul.ac.uk/mpurver/papers/purver04thesis.pdf

Roberts, C.: Modal subordination, anaphora, and distributivity. Dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst (1987)

Rooth, M.: A theory of focus interpretation. Nat. Lang. Semant. 1, 75–116 (1992)

Schegloff, E., Jefferson, G., Sacks, H.: The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language 53(2), 361–382 (1977)

Shriberg, E.: Preliminaries to a theory of speech disfluencies. Dissertation, University of California at Berkeley (1994)

Stalnaker, R.: Assertion. Syntax Semant. 9, 315–332 (1978)

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Pranav Anand, Donka Farkas, Andreas Walker, Paul Willis, Erik Zyman and the audiences at the UCSC S-Circle (October 2015), CUSP (Stanford, November 2015), the UCSC SPLAP Workshop (February 2016), CoCoLab (Stanford, March 2016) and three WoLLIC reviewers for discussion and comments on this work. The usual disclaimers apply.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

A Categorial Grammar Formulation

A Categorial Grammar Formulation

Here we present an alternative syntactic account of error correction structures in categorical grammar that preserves our semantic account. For reasons of space we suppress non-propositional drefs, and work through non-quantified cases only. For full sentence corrections, the correction denotes a binary relation between sentences that updates the common ground only with the proposition associated with the correction:

To handle partial corrections we generalize the type of the correction structure to denote a relation between verb phrases. The correction essentially builds a conjunction in which only the conjunct associated with the correction is added to the common ground.

The correction then takes the subject as its final argument resulting in the desired update:

We also need to handle error correction structures which contain material between the correction and the constituent that needs to be replaced. This material needs to be made available both to the anchor and the correction. We utilize a pair forming operator \(\circ \) that creates pairs of semantic values:

We now analyze error correction structures with intervening material in terms of pair formation. The correction, taking a verb to its right as its first argument, expects a verb-object pair to its left. It then feeds the object to both verbs:

The correction then takes the subject as its final argument, and generates the desired update:

This account avoids movement of the intervening material at the cost of introducing a pair-forming operator. This operator allows us to store the semantic value associated with the object so that it can be used to saturate the verb in both the anchor and the correction.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this paper

Cite this paper

Rudin, D., DeVries, K., Duek, K., Kraus, K., Brasoveanu, A. (2016). The Semantics of Corrections. In: Väänänen, J., Hirvonen, Å., de Queiroz, R. (eds) Logic, Language, Information, and Computation. WoLLIC 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 9803. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-52921-8_22

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-52921-8_22

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-662-52920-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-662-52921-8

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)