Abstract

In research, farm management may be approached from the perspective of economic rationality or studied using sociologically-inflected approaches. This article invites researchers to reflect upon the – often implicit – assumptions underlying their chosen research approach, regarding the rationality of family farmers and the dynamics of the broader context in which they manage their farm. To illustrate how different these assumptions may be, the article contrasts two ideal types, economic versus peasant rationality. They can be linked to different worldviews and lead to distinct recommendations for farm management: while one builds on a mechanistic worldview and promotes planning, the other builds on a complexity worldview and bolsters bricolage. Being aware of the assumptions underlying our research is important, not least given the performativity of research.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Broadly speaking, empirical research that focuses on the management of family farms may take either a normative, economic-inflected approach, or a descriptive, sociologically-inflected approach. The two approaches characterize farmers as following different rationalities: an ‘economic rationality’ framing farmers as rational decision-makers striving to improve the efficiency of resource use to ensure sound cost-benefit ratios, and to maximize income despite various constrains on how they can use their resources; or a ‘peasant rationality’, where subjective perception, individual preferences, and social norms play important roles in shaping farmers’ choices. By looking at the implicit assumptions underlying these two rationalities, it becomes evident that they are not only tied to different disciplinary backgrounds, but also to different worldviews. These assumptions about the world and its dynamics lead to quite different recommendations about how to effectively ensure the long-term survival of the farm, given that intra-familial succession is the ultimate aim of most family farmers (see Fischer and Burton 2014).

The aim of this article is to surface some of the – often implicit – assumptions underlying economic-inflected approaches and to contrast them with those of sociologically-inflected research on decision-making by family farmers. The focus is on two aspects that are key when studying family farms: first, assumptions about farmers’ rationalities, and second, conceptions of the dynamics of the broader context in which farmers manage their farm. The two conceptualizations, of rationalities and of the context, are interdependent, and result in quite different recommendations for family farm management.

By comparing and contrasting two ideal-type conceptualizations, I want to draw attention to the importance of being be aware of the assumptions underlying one’s chosen research approach, as they will guide what is perceived as relevant and effective in ensuring the long-term survival of the farm. This is consequential, not least given the performativity of research.

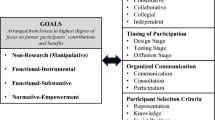

2 Economic versus Peasant Rationality

To clarify the assumptions that underly our approach to the logic of decisions made by family farmers, and thus what is considered as a ‘rational’ choice, I contrast two ideal-type rationalities: the economic manager and the peasant (see Table 1). Economic rationality is built on understanding farmers as ‘managers’, which is often done in farm management textbooks and is underlying many tools used in farm economics. This understanding frames the farm as an economic enterprise that should be managed like any other profit-oriented business, i.e., its management should follow an instrumental rationality, based on a systematic, objective calculation of profit and loss, thus allowing the efficient use of resources to produce goods and services, with the overall aim of capital accumulation. Farmers’ choices are thus guided by the logic of supply and demand in product markets, average interest rates in capital markets, and wage rates in labor markets.

Framing a farm as a for-profit business like any other implies that the distinctive features of family businesses (Simon 2012) and the specificities of family farms (see Schneeberger 2011, pp. 442) are not considered. However, the tight coupling of the family and the farm has major implications for the rationality underlying the choices in the use of two important production factors: capital and labor. Indeed, how a family deploys its capital is subject to a different logic than that of shareholders. These are likely to sell their shares on short notice, if they think their capital is better invested in another company which promises a higher rate of return. Yet, on a family farm, the capital (land, building, machinery, savings, etc.) has first and foremost a use value, i.e., it is a resource that enables the family to earn a living. Indeed, “if profit was the aim people would surely sell their land” (van der Ploeg 2013, p. 29). Similarly, it can be misleading to treat family labor like wage labor – which is implicitly done when family labor is valued at current wage rates. As Simon (2012, pp. 32) points out, there are numerous differences between the labor provided by employees and work performed by family members: the value of a family member cannot be reduced to the value of the labor he or she provides; family members are not interchangeable the way employees are; the role and function of family members change flexibly rather than being formalized in a contract; the ‘give and take’ is assessed subjectively over the long term rather than being set by formal contracts and monthly wages; within the family achievements are rewarded through emotional relations rather than in monetary terms; and the benefits of working on the family farm are primarily meaningful and identity-building rather than material or monetary.

The distinctive features of a family farm take a more prominent place in sociologically-inflected approaches such as the ‘peasant rationality’ (Niska et al. 2012; van der Ploeg 2008, 2013, 2018). Within this rationality (see Table 1), family farmers do not ignore profit, but they do not prioritize it, as the aim is not short-term profit maximization, but the long-term prosperity of the farm. The focus on the long-term implies juggling competing demands such as economic constraints and the wellbeing of all family members, or personal preferences in production methods, and social norms in peer networks and the local community. Focusing on the long-term, family farmers are aware of the need to adapt and fine-tune activities in response to changes in the social, economic, and technological environments off-farm, but also to changes on-farm such as shifts in the interests or preferences of family members or the available labor over the course of the family’s generational cycle. To account for these changes and enable adaptiveness, peasant rationality is characterized by a constant quest for relative autonomy, not least from market forces. This autonomy is understood as key to preserving the freedom to do things one’s own way by maintaining a self-controlled and self-managed resource base (Stock and Forney 2014).

3 Mechanistic versus Complex System Worldview

Differences between the ideal types of economic and peasant rationality are not limited to distinct emphases guided by disciplinary backgrounds such as focusing on market integration versus a search for autonomy, or whether family labor is akin to wage labor versus the two being incommensurable. Indeed, each rationality can be linked to an underlying worldview. This worldview is a set of assumptions about the world, i.e., the broader context in which farmers make choices, and in particular whether it is understood as stable and predictable or as ever-changing, often in unpredictable ways. Researchers’ assumptions about the dynamics of this context, which family farmers need to navigate to persist over the long-term, will influence what kinds of strategies are considered effective and thus recommended.

The world can be seen as broadly predictable, as unfolding along a determined, and thus knowable, trajectory. This understanding frames the world as a mechanistic system, a view that can be traced back to René Descartes, who stated in the 17th century that the universe is akin to a machine (Garber 2002). Viewing the world as a machine, allows to approach it through an engineering lens. Just like a machine, the world is assumed to be orderly and stable, its functioning known, the outcome of actions predictable. Thus, the relevant ecological, social, and political context, in which farmers take decisions, is seen as broadly predictable. The laws of supply and demand underlying agricultural markets are seen as unchanging. Since the world is stable and cause-effect relations can be understood well enough, the future can be predicted based on models. Thus, future changes in demand or prices can be considered in mathematical models, and the risks associated with long-term investments can be assessed. Volatility thus becomes a mathematical variable, that can be observed and calculated; the profitability of investments and ongoing activities can be predicted. This worldview allows for finding ways to control situations, i.e., to bring a farm into a predetermined, predictable state. The mechanistic worldview enables formal planning and design, and allows for the establishment of strategies to achieve predetermined goals (Duymedjian and Rüling 2010; Johnson 2012).

In farm economics, this worldview is expressed in the effort to optimize activities on a farm by using production functions, that assume a clear link between inputs and outputs, and their respective market prices. Linking these production functions to market demand and the resources available on a farm, allows to compute the optimal combination of activities and the most efficient production levels for each activity. Such models, with some sensitivity analyses, can be used for planning, since both the outcomes of choices and the probabilities of various outcomes are known. This allows to assess risks stemming from shifts in prices of inputs or outputs.

In a world understood as a mechanistic system, a farmer is akin to an engineer, working to implement a pre-set, well-defined project, executing a clearly laid-out plan, using raw materials efficiently, and employing machinery specially designed for each task (see Jacob 1977). The trajectory of a farm over time is thus the result of implementing a carefully planned strategy, based on the optimal use of available resources, and the closely controlled execution of a predefined plan. Such a ‘command-and-control’ approach implicitly assumes that “the problem is well-bounded, clearly defined, relatively simple and generally linear with respect to cause and effect” (Holling and Meffe 1996, p. 329).

The mechanistic worldview can be contrasted with conceptualizing the world as a complex system (see Table 2). A complex system is “a system that exhibits nontrivial emergent and self-organizing behaviours” as it changes and adapts via learning and evolution (Mitchell 2009, p. 13). In this worldview, future developments are unpredictable, surprises are the rule, and opportunities emerge in unexpected ways. The system is in an open process of becoming (Morin 2008). Any order is the precarious result of an ongoing process, it cannot be derived from a specific structure. There is no determinism, as cause-effect relations depend on various ecological, social, and political processes. As these processes interact, they change, often in unpredictable ways, i.e., there are many unforeseen developments and unexpected events (Chia 1999; Tsoukas and Chia 2002).

Assuming the world is a complex adaptive system, farmers are understood as part of an unfolding, open-ended process, in which they must take ‘appropriate’ action (Jullien 2004). What is appropriate depends on how the context unfolds and how desirable the various options appear. Since one cannot know in advance what is appropriate, what will ‘work’, it seems judicious to follow a trial-and-error process, a stepwise ‘tinkering’ (Jacob 1977), an approach akin to ‘improvisation’ by jazz musicians (Weick 1998). These strategies enable to work with the unforeseen by relying heavily on simple heuristics (Gigerenzer 2008), an intuitive grasp of the unfolding situation (Burke and Miller 1999), allowing a mix of routine and novelty. The trajectory of a farm is thus akin to biological evolution, in which current species reflect a historical process full of contingencies (see Jacob 1977).

4 Assumptions Shaping Recommendations for Farm Management

Researchers’ assumptions about farmer rationality and about the dynamics of the broader context are interrelated. The ideal type of economic rationality is well aligned with the view of a fairly predictable world, as this allows recommendations for farm management to be informed by rational planning, based on the assumption that key variables are known well enough, can be quantified, and thus integrated into economic models. If researchers assume the world to be orderly, i.e., developing along a predictable trajectory, they can develop plans for the future based on probabilities derived from past events. This assumption enables precise recommendations on the most efficient use of resources, materials, and technologies.

Any deviation from the plan is a digression, an irregularity that needs to be corrected. The challenge is primarily in the intellectual planning process. Once the strategy for a farm has been defined, the farmer only has to unroll it, as the implementation, the doing, is seen as unproblematic (see Fig. 1). And indeed, in organizational theory, emphasis is on stability, order, and control; reliance on routine, habit, and repetition; a privileging of reliability, formalization, and standardization (Weick 1998).

Illustration by Simon Kneebone for the author, CC BY 4.0, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16726444

Farm management guided by rational planning: A predefined plan derived from economic models is implemented as-is.

In contrast, peasant rationality and its emphasis on autonomy and adaptability is consistent with an understanding of the world as a complex, adaptive system, fraught with surprises. Indeed, complexity means that no matter how carefully a project is planned, many processes beyond the farmer’s control will influence how the project will actually unfold. Thus, the key to persistence over the long-term is not to plan ever more carefully, but to remain responsive, to nurture the ability to engage with processes as they unfold, by (re)assembling resources differently (Darnhofer 2021; St. Martin et al. 2015). Indeed, this enables a co-evolution between projects and contexts, responding to changing opportunities with new ways to achieve goals, a creative process that uses the emerging dynamics to the farm’s advantage (Fig. 2).

Illustration by Simon Kneebone for the author, CC BY 4.0, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16726441

Farm management guided by bricolage: Engaging in activities reveals new opportunities.

Thus, while farmers are understood as having aims and goals, e.g., regarding quality of life, income level, or preferred farming practices, the way in which these are realized remains open to the opportunities as they emerge, and they may well change as a result of experience and learning.

This leads to an understanding of farm management akin to ‘bricolage’. Bricolage is generally understood as taking whatever is at hand and recombining it to create something new; it implies often using things (or ideas) beyond purposes they were originally meant for (Duymedjian and Rüling 2010; Feyereisen et al. 2017; Johnson 2012). Bricolage builds on material and immaterial resources that are collected independently of a particular project. Bricoleurs accept that materials may not be ideal, embrace imperfections as they help them achieve their goals, allowing them to improvise and test solutions which are understood as provisional (Grivins et al. 2017). A bricolage approach conceptualizes farmers as ‘muddling through’ (Lindblom 1959), an ability built on knowing about the uses of things and their possibilities, a knowledge that comes through interacting with the world. Indeed, it is through this interaction that new ideas and new ways of doing emerge. This implies that sense-making, decision-making, and acting are not separate in time (Weick 1998). In other words, a bricolage approach implies that farmers do not primarily think ahead conceptually and intellectually, but think through being constantly immersed in practices with things and in activities with others.

5 In Lieu of a Conclusion: An Invitation to Reflect on the Implications of Assumptions Underlying Research

By comparing and contrasting two ideal-types that can be used to characterize farmer rationality and by linking them to broader worldviews, this article aims to illustrate the importance for researchers to be aware of the assumptions underlying the research approach of their choice. Indeed, assumptions influence the methods used in empirical studies, the data collected, the aspects considered relevant and thus foregrounded in the analysis, and those that are disregarded. As a result, they will guide the recommendations derived from empirical research, i.e., the possibilities considered feasible for future farm development and the management strategies perceived as promising to ensure that family farms thrive over the long-term.

Clearly, any research approach needs to make assumptions, and every empirical study has to select aspects on which to focus. Thus, each research approach will highlight some aspects while obscuring others, often leading to different recommendations. Approaching farm management through quantification, mathematization, and formalization, allows to gain rigor and derive specific recommendations intent to increase the economic profitability of farms. Yet, this approach may well reduce complexity by fragmenting the farm, by disjoining the actions, interactions, and feedback loops that link technical, biological, and social processes. Approaching farm management by taking complexity seriously, means acknowledging that many real-life situations are ‘wicked’ rather than ‘tame’ (see Rittel and Webber 1973). The future is thus conceptualized as ambiguous and uncertain, so recommendations will emphasize strategies for coping with unpredictability, ambiguity, contradictions, and surprises (see Law 2004). As a result, recommendations for farm management will privilege flexibility, adaptability, and bricolage.

The choices researchers make are not innocent. Researchers, who are aware of the assumptions underlying their approach will choose theories and methods carefully. This awareness will avoid inappropriately conflating concepts and will ensure that required distinctions are made. Indeed, it can be misleading to tame unpredictability through theories of chance, to reduce uncertainty to risk, and to conceptualize chaotic events as calculable (Mol and Law 2002). If a mechanistic approach is taken to comprehend a situation characterized by complexity, surprising events may be labeled as anomalies and thus marginalized, instead of being understood as a key dynamic of the system under consideration.

It might not be enough for researchers to ask themselves whether their assumptions fit the world or whether their simplifications are justified. For example, it is widely accepted that the behavioral assumptions underlying neoclassical economic theory and “homo economicus” lack realism (see e.g., Fullbrook 2004; Söderbaum 2008). Yet, they still form the implicit basis of many economic models, with the argument that they enable mathematical modelling and approximation.

Perhaps more importantly, researchers need to be aware that their assumptions about farmers influence the world that their research brings about. In other words, they need to consider the performativity of economics (Brisset 2019; Callon 2007; MacKenzie 2006; MacKenzie et al. 2007) and of research in general (Aggeri 2017; Daniel 2011). Taking performativity seriously invites researchers to consider the wider impact of their research, i.e., that it may be more ‘effective’ than anticipated. Indeed, research not only describes the world as it is, but also enacts it (Callon 2015; Law and Urry 2004; St. Martin et al. 2015). Researchers are therefore invited to reflect on the kinds of worlds their research performs, i.e., what it contributes to make visible and to bring about.

References

Aggeri, F. (2017). How can performativity contribute to management and organization research? M@n@gement, 20(1), 28–69. Retrieved October 1, 2021, from https://www.cairn-int.info/journal-management-2017-1-page-28.htm.

Brisset, N. (2019). Economics and Performativity. Exploring Limits, Theories and Cases. London, UK: Routledge.

Burke, L., & Miller, M. (1999). Taking the mystery out of intuitive decision making. Academy of Management Executive, 13(4), 91–99.

Callon, M. (2007). What does it mean to say that economics is performative? In D. MacKenzie, F. Miniesa, & L. Siu (Eds.), Do Economists Make Markets? On the Performativity of Economics (pp. 311–357). Princeton, NJ, US: Princeton University Press.

Callon, M. (2015). How to design alternative markets. The case of genetically modified/non-genetically modified coexistence. In G. Roelvink, K. St. Martin, & J. K. Gibson-Graham (Eds.), Making Other Worlds Possible. Performing Diverse Economies (pp. 322–348). Minneapolis, MN, US: University of Minnesota Press.

Chia, R. (1999). A ‘rhizomic’ model of organizational change and transformation: Perspective from a metaphysics of change. British Journal of Management, 10(3), 209–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00128.

Daniel, J.-F. (2011). Action research and performativity: How sociology shaped a farmers’ movement in the Netherlands. Sociologia Ruralis, 51(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2010.00525.x.

Darnhofer, I. (2021). Resilience or how do we enable agricultural systems to ride the waves of unexpected change? Agricultural Systems, 187, 102997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102997.

Duymedjian, R., & Rüling, C.-C. (2010). Towards a foundation of bricolage in organization and management theory. Organization Studies, 31(2), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840609347051.

Feyereisen, M., Stassart, P., & Mélard, F. (2017). Fair trade milk initiative in Belgium: Bricolage as an empowering strategy for change. Sociologia Ruralis, 57(3), 297–315, https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12174.

Fischer, H., & Burton, R. (2014). Understanding farm succession as socially constructed endogenous cycles. Sociologia Ruralis, 54(4), 417–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12055.

Fullbrook, E. (Ed.) (2004). A Guide to What’s Wrong with Economics. London, UK: Anthem Press.

Garber, D. (2002). Descartes, mechanics and the mechanical philosophy. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 26(1), 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4975.261061.

Gigerenzer, G. (2008). Rationality for Mortals. How People Cope with Uncertainty. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press.

Grivins, M., Keech, D., Kunda, I., & Tisenkopfs, T. (2017). Bricolage for self-sufficiency: An analysis of Alternative Food Networks. Sociologia Ruralis, 57(3), 340–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12171.

Holling, C., & Meffe, G. (1996). Command and control and the pathology of natural resource management. Conservation Biology, 10(2), 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10020328.x.

Jacob, F. (1977). Evolution and tinkering. Science, 196(4295), 1161–1166. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.860134.

Johnson, C. (2012). Bricoleur and bricolage: From metaphor to universal concept. Paragraph, 35(3), 355–372. https://doi.org/10.3366/para.2012.0064.

Jullien, F. (2004). A Treatise on Efficacy. Between Western and Chinese Thinking. Honolulu, HI, US: University of Hawai’i Press.

Law, J. (2004). After Method. Mess in Social Science Research. Abingdon, OX, UK: Routledge.

Law, J., & Urry, J. (2004). Enacting the social. Economy and Society, 33(3), 390–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/0308514042000225716.

Lindblom, C. (1959). The science of ‘muddling through’. Public Administration Review, 19(2), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/973677.

MacKenzie, D. (2006). Is economics performative? Option theory and the construction of derivative markets. Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 28(1), 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10427710500509722.

MacKenzie, D., Miniesa, F., & Siu, L. (2007). Do Economists Make Markets? On the Performativity of Economics. Princeton, NJ, US: Princeton University Press.

Mitchell, M. (2009). Complexity. A Guided Tour. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press.

Mol, A., & Law, J. (2002). Complexities: An introduction. In J. Law, & A. Mol (Eds.), Complexities. Social Studies of Knowledge Practices (pp. 1–22). Durham, NC, US: Duke University Press.

Morin, E. (2008). On Complexity. Advances in Systems Theory, Complexity, and the Human Sciences. Cresskill, NJ, US: Hampton Press.

Niska, M., Vesala, H., & Vesala, K. (2012). Peasantry and entrepreneurship as frames for farming: Reflections on farmers’ values and agricultural policy discourses. Sociologia Ruralis, 52(4), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2012.00572.x.

Rittel, H., & Webber, M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730.

Schneeberger, W. (2011). Der landwirtschaftliche Betrieb. In W. Schneeberger & H. Peyerl (Hrsg.), Betriebswirtschaftslehre für Agrarökonomen (S. 421–456). Wien, Österreich: Facultas.

Simon, F. (2012). Einführung in die Theorie des Familienunternehmens. Heidelberg, Deutschland: Carl Auer.

Söderbaum, P. (2008). Understanding Sustainability Economics. Towards Pluralism in Economics. London, UK: Earthscan.

St. Martin, K., Roelvink, G., & Gibson-Graham, J. K. (2015). An economic politics for our times. In G. Roelvink, K. St. Martin, & Gibson-Graham, J. K. (Eds.), Making Other Worlds Possible. Performing Diverse Economies (pp. 1–25). Minneapolis, MN, US: University of Minnesota Press.

Stock, P., & Forney, J. (2014). Farmer autonomy and the farming self. Journal of Rural Studies, 36, 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.07.004.

Tsoukas, H., & Chia, R. (2002). On organizational becoming. Organization Science, 13(5), 567–582, https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.5.567.7810.

van der Ploeg, J. D. (2008). The New Peasantries. Struggles for Autonomy and Sustainability in an Era of Empire and Globalization. London, UK: Earthscan.

van der Ploeg, J. D. (2013). Peasants and the Art of Farming. A Chayonavian Manifesto. Halifax, NS, Canada: Fernwood Publishing.

van der Ploeg, J. D. (2018). The New Peasantries: Rural Development in Times of Globalization. London, UK: Earthscan.

Weick, K. (1998). Introductory essay – Improvisation as a mindset for organizational analysis. Organization Science, 9(5), 543–555. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.9.5.543.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access Dieses Kapitel wird unter der Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de) veröffentlicht, welche die Nutzung, Vervielfältigung, Bearbeitung, Verbreitung und Wiedergabe in jeglichem Medium und Format erlaubt, sofern Sie den/die ursprünglichen Autor(en) und die Quelle ordnungsgemäß nennen, einen Link zur Creative Commons Lizenz beifügen und angeben, ob Änderungen vorgenommen wurden.

Die in diesem Kapitel enthaltenen Bilder und sonstiges Drittmaterial unterliegen ebenfalls der genannten Creative Commons Lizenz, sofern sich aus der Abbildungslegende nichts anderes ergibt. Sofern das betreffende Material nicht unter der genannten Creative Commons Lizenz steht und die betreffende Handlung nicht nach gesetzlichen Vorschriften erlaubt ist, ist für die oben aufgeführten Weiterverwendungen des Materials die Einwilligung des jeweiligen Rechteinhabers einzuholen.

Copyright information

© 2022 Der/die Autor(en)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Darnhofer, I. (2022). Researching the Management of Family Farms: Promote Planning or Bolster Bricolage?. In: Larcher, M., Schmid, E. (eds) Alpine Landgesellschaften zwischen Urbanisierung und Globalisierung. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36562-2_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-36562-2_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN: 978-3-658-36561-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-658-36562-2

eBook Packages: Social Science and Law (German Language)