Abstract

The focus in this chapter is on the local politics of Rotterdam and especially the local political turnover of power in 2002. Up until that year, during the time Rotterdam changed into a superdiverse city, the Labour Party had always been the largest political party in Rotterdam. In 2002 however, a new party won the elections with almost 37% of the votes. This victory is strongly associated with Pim Fortuyn, the party’s leader. Fortuyn, who by many was considered a populist, applied a fierce anti-establishment attitude and had been known for, among other things, critique on integration policy and the Islam. In this chapter, attention is given to the policy and political debate regarding immigration and integration before, during, and after this change of power. From an international perspective, this case sheds light on the question whether and how a populist/anti-establishment party can succeed to not only win elections, but to implement policy. Liveable Rotterdam was part of Rotterdam government from 2002 to 2006 (and became part of it again in 2014).

Parts of this chapter have previously been published in my dissertation: Van Ostaaijen 2010.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

The focus in this chapter is on the local politics of Rotterdam and especially the local political turnover of power in 2002. Up until that year, during the time Rotterdam changed into a superdiverse city, the Labour Party had always been the largest political party in Rotterdam. In 2002 however, a new party won the elections with almost 37% of the votes. This victory is strongly associated with Pim Fortuyn, the party’s leader. Fortuyn, who by many was considered a populist, applied a fierce anti-establishment attitude and had been known for, among other things, critique on integration policy and the Islam. In this chapter, attention is given to the policy and political debate regarding immigration and integration before, during, and after this change of power. From an international perspective, this case sheds light on the question whether and how a populist/anti-establishment party can succeed to not only win elections, but to implement policy. Liveable Rotterdam was part of Rotterdam government from 2002 to 2006 (and became part of it again in 2014).

1 Rotterdam Politics Up Until 2002

In the Dutch and Rotterdam system of local government, many actors are involved in policy-making. This makes the Dutch system a fragmented system in which power is divided among several directly and non-directly elected actors, among which a directly elected municipal council (gemeenteraad) and a day-to-day political executive (college). The executive consists of aldermen (wethouders) who are appointed by (a majority in) the council and a mayor (burgemeester), who is formally appointed by national government, but that appointment is influenced by the council (Van Ostaaijen 2010).Footnote 1

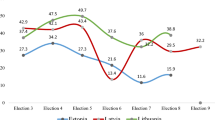

The municipal council in Rotterdam consists of 45 seats divided between several political parties. With an average of 20 municipal council seats in the post-war elections, the Labour Party had consistently been the largest party in the municipal council. It even received an absolute majority (23 seats or more) for 16 years, from 1962 to 1966, 1974 until 1982, and from 1986 to 1990.

In the first two decades after the Second World War, Rotterdam politics experienced a time of consensus and of little political differences (Van de Laar 2000). Everyone considered rebuilding the harbour and the city to be undisputed priorities. Political differences became evident only during elections. But after elections, the Labour Party normally granted other parties a place in the municipal executive and political disputes subsided. Even in 1962, when the Labour Party gained the absolute majority in the municipal council for the first time, it took the Liberal Party and Christian Democratic Party aboard as partners in the executive (Table 5.1).

During the elections of 1990 and 1994, the Labour Party lost a substantial proportion of its seats. However, it remained the largest party with a considerable number of council seats more than the second largest party (the Christian Democratic Party in 1990 and the Liberal Democratic Party in 1994). This gave the party influence in coalition negotiations in order to form the executive. And when the Labour Party was again able to win seats in 1998, it could make more demands. Compared to the previous period (1994–1998), the Labour Party received one alderman more and the Liberal Party had to hand over the harbour portfolio to the Labour Party. Criticism from opposition parties about this concentration of power was dismissed by the Labour Party (municipal council meeting 14/4/1998). Even though Rotterdam was thus up until 2002, a Labour Party dominated city – even the Rotterdam municipal service departments were often led by Labour Party members (e.g. see: Labour Party 2002: 7) – this does not mean, governing always went smoothly. The 1998–2002 executive continued some disputes from the previous executive. According to national newspapers, the 1994–1998 executive performed poorly and there was only minimal funding available to implement the new 1998 programme. Moreover, there were misunderstandings between some of the important Labour Party aldermen and (Labour Party) mayor Peper. Both aldermen at some point even complained about the mayor to the prime minister, also from the Labour Party. Nevertheless, the executive was able to make extra money available for the European Football Championship in 2000 and the appointment of Rotterdam as European Cultural Capital in 2001.

2 Coming to Terms with Superdiversity Prior to 2002

While Rotterdam’s political leadership remained relatively stable due to the Labour Party’s dominance, the city’s social structure changed substantially. That this change also caused social anxieties was for instance expressed in 1972, when some neighbourhood inhabitants threw the furniture of immigrants into the streets. This was later labelled as Rotterdam’s first race related riots after the Second World War. Afterwards, the executive proposed to distribute the population of ‘foreigners’ throughout the city, allowing only 5% in each neighbourhood (Dekker and Senstius 2001: 23). The Dutch Council of State however blocked the measure because of its discriminatory character (Van Praag 2004: 68). A few years later, Rotterdam tried again. This time, it won a legal fight to install a maximum of 16% non-Dutch people in any neighbourhood. However, this time the executive did not follow through with the plans.

The 1978 policy report ‘Migrants in Rotterdam’ (Migranten in Rotterdam) acknowledged that foreign immigrants – then referred to as guest labourers – were often not returning to their country of origin. This revelation paved the way for an integration policy (Dekker and Senstius 2001), even though the beginning of the report indicates otherwise: “no distinction is made between people of Dutch origin and people of foreign origin … one policy is waged for both groups” (quote of the 1978 programme cited in Rotterdam 1998b).

In 1986, civil servants from city hall organised a series of dialogues between mosque organisations and a Labour Party alderman. The themes included employment and gender relations. In the 1990s, more attention emerged regarding the efforts immigrants have to exert in order to make a living. The next phase of dealing with immigrants started in 1998. In 1998, the document ‘Effective Immigrant Policy’ (Effectief Allochtonenbeleid) acknowledged that the view of the 1978 report was no longer sustainable. Rotterdam no longer consisted of a homogenous Dutch population, but an ethnic heterogeneous one, which required the application of ‘specific arrangements’ (Rotterdam 1998b: 2). The executive strongly encouraged that all services in Rotterdam took this reality into consideration when developing policy. The executive encouraged hiring more inhabitants of foreign origin to make the city organisation more representative of its population. It also recommended the development of ‘diversity in communication’, e.g. addressing inhabitants in different languages (RD 10/11/2000).

Diversity is a fact, and as such does not require discussion… ‘Inclusive’ thinking (meaning diversity is the norm and the starting point in every policy area) should be stimulated within every executive plan, service, institution, and politics. This means that every activity, every policy proposal should be measured to see if it fulfils the aim of diversity… Too often it is forgotten that general policy starts from thinking from Dutch middle-class groups, while it already is necessary (especially in certain areas) to change towards diversity policy… [We have to] challenge inhabitants from a foreign origin to make their contribution to Rotterdam society concrete in the form of wishes, desires, and possibilities. (Rotterdam 1998a: 5, italics added)

Even though all these years the Labour Party remained the largest party in Rotterdam politics, some electoral signals emerged that not all inhabitants felt comfortable with the Labour Party’s stand on integration. In the 1980s, several extreme right parties made immigration and integration issues their main campaign themes, mainly by being against it. The extreme right won one municipal council seat in 1986, two in 1990, and six in 1994. In 1998, these parties did not win a single municipal council seat. However, the rapid growth of the extreme right parties had nevertheless also caused some of the public avoidance of problems with immigration and integration lest these issues be exploited for political purposes, and this avoidance contributed to the taboo on public debate over certain problems (e.g. Linthorst 2004: 212). According to some top city managers, the focus on diversity policy within the municipal services also meant that certain (socioeconomic) problems of these groups were not addressed.

The crime numbers came in and tilted strongly towards our coloured fellow human beings, especially the Moroccans. This was thus nuanced and trivialised, that was the sphere… It just was not politically correct to address it. (interview former top civil servant, Van Ostaaijen 2010)

In the evaluation of the 1998–2002 executive programme there was no reference to such tensions or problems. The executive mainly emphasised policy successes. In the evaluation of the ‘multi-coloured city’ programme, the executive regarded the focus on personnel policy as most successful as the percentage of employees of foreign origin grew from 16.3% to 18.1% (Rotterdam 2001: 48). As we can also see in Chap. 10, general opinion of Dutch citizens at this time was not always positive.

3 The Emergence of Pim Fortuyn, Liveable Rotterdam, and Local Populism in Rotterdam Politics 2001–2002

Pim Fortuyn (1948–2002) started his career in science. In 1990, Fortuyn was appointed as part-time professor at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the city where he had lived since 1988. In the 1990s, Fortuyn achieved attention with his writings, such as books and columns, and speeches where he mainly criticised the degradation of old urban neighbourhoods, the multicultural society, Islam, the educational system, bureaucracy, and the welfare state. In his appearance, Fortuyn was considered a dandy. He had shaved his head since 1997and was rarely seen without a fancy suit with thick tie. He spoke eloquently, lived alone with his butler and two dogs, and never hid the fact that he was gay when asked about it. In August 2001, Fortuyn declared on national TV that he entered Dutch politics to become prime minister of the Netherlands, either with an existing party or his own list of candidates. After his announcement to become a politician, the media started reporting on Fortuyn. His ambition and comments on immigration gave him more media coverage and increased his fame. In January 2002, Fortuyn became a member of Liveable Rotterdam, a local party in his home town of Rotterdam.

Liveable Rotterdam was established only 1 month earlier by a former school teacher called Ronald Sørensen, partly out of affinity with Fortuyn. Sørensen decided to take part in the municipal council election and he quickly established an organisation, a programme, and a list of candidates. He had to do that quickly since the election was only 3 months away (in March 2002). Some of Sørensen’s friends joined the party as well and he hoped to win five municipal council seats in the 2002 election.

After Fortuyn sent Sørensen an email to become a member of Liveable Rotterdam, things proceeded rapidly. One week after the email, there was a meeting in Fortuyn’s home where it was agreed that Fortuyn would become leader of Liveable Rotterdam, which meant that he would lead the list of municipal council candidates for the upcoming election in March 2002. Besides his affinity with Rotterdam, the reason for Fortuyn to accept was that he considered the Rotterdam municipal council election a good test case for his national ambitions and the national election in May 2002. At the meeting where the decision was made to make Fortuyn the leader of Liveable Rotterdam, someone asked about Liveable Rotterdam’s election programme. Sørensen wanted to answer, but Fortuyn interrupted him and mentioned issues such as safety, the deteriorated neighbourhoods, and flight of the middle-class (Chorus and De Galan 2002: 124–125; Oosthoek 2005: 40).

In 2002, the national media devoted more and more attention to Fortuyn, who appeared to take Dutch politics by storm. Proponents and opponents agreed that he knew how to use the media and the media were fond of reporting on him. Fortuyn’s national message, in which safety, immigration and Islam stood out as main themes, seemed to appeal to voters, also in Rotterdam. According to a poll in Rotterdam in the end of January, Liveable Rotterdam would be able to secure a maximum of ten municipal council seats, about 22% of the votes. By the beginning of February this had become 12 seats. In March the number fell back to ten. In these polls, however, Liveable Rotterdam never secured more council seats than the Labour Party. Those same polls also included a question about the problems in the city. In all three polls, safety and street crime were considered the largest problems (Oosthoek 2005: 82).

When Fortuyn became the leader of Liveable Rotterdam in January 2002, his views dominated the party agenda to a large extent. Therefore his (inter)views and writings together with the formal election program of Liveable Rotterdam determine the party’s agenda of which improved safety (policy), but also a stricter immigration and integration approach, or at least more open discussion about related problems, were important parts (Van Ostaaijen 2010).Footnote 2

Focusing on immigration and integration, a theme Fortuyn became known for in his writings, the election programme stated: ‘Liveable Rotterdam is a party that wants to fight all forms of racism and discrimination based on race, religious conviction, nationality, heritage, or gender’ (Liveable Rotterdam 2002). The party does not tolerate opposition to hard-fought changes, such as democracy, separation of church and state, women’s right to vote, workers’ rights, social insurance, and equality for women and gays; immigrants should receive educational support, but also have an obligation to integrate themselves (Liveable Rotterdam 2002).

Fortuyn was in favour of women’s emancipation, including ethnic women, but he did not believe in a multicultural society in the sense of different cultures living next to but not with each other. Fortuyn was very much in favour of ‘free speech’ to discuss these and other issues in the open. During the election campaign, Fortuyn even said that he wanted the ban on discrimination excluded from the Dutch Constitution as it limited the right to free speech too much. He was in favour of an open, rigorous debate (Chorus and Galan 2002: 199). He explained:

The leftist church, which includes part of the media, the Green Party and the Labour Party, has for years forbade discussions that deal with the multicultural society and the problems it brings forth, by continuously combining those with discrimination, with racism, and not in the last place, with the blackest page of the history of this part of the continent: fascism and Nazism. (Fortuyn cited in Chorus and Galan 2002: 198)

In the 1990s, Fortuyn wrote about Islam in a book called ‘Against the Islamisation of Our Culture’ (Fortuyn 1997). During the election campaign he said that the Islamic culture is a backward one and that if he could legally arrange it, there would be no Muslim allowed to enter the country (Volkskrant 9/2/2002). In the summer of 2001, he gave an interview in the Rotterdam local paper claiming that the number of immigrants was a problem:

The Netherlands is full. Rotterdam as well. In a couple of years, this city will consist for 56% of people who are not from the Netherlands… We allow too many foreign people to enter. In that way we get an underclass that consists of too many people who are badly equipped to contribute either economically or culturally. (Oosthoek 2005: 25)

Fortuyn believed that everyone who was already in the Netherlands could stay and should be taken care of, but no more should be allowed to enter before the country had solved its problems, since, he said, most newcomers have a difficult time taking care of themselves, let alone contributing to society. Moreover, he believed that people who had migrated should adjust to the dominant culture. Fortuyn was also a proponent of mixing different cultures throughout the city and of building more houses for the middle-class.

Fortuyn, party founder Sørensen, and party member Pastors (who later became alderman), denied being anti-immigrant or racists. Sørensen wanted the election programme to include measures for the integration of immigrants, but not their removal from the country. He also took a councilman candidate off the candidate list when he found out that he had been a member of an extreme-right party (Booister 2009: 59, 82). Fortuyn thought migrants could be good role models for other citizens and declared that he had many immigrant friends (Booister 2009: 48). When Pastors was invited to become part of Liveable Rotterdam, he wanted to know for sure that the party was no ‘right-wing club’ as he did not ‘hate foreigners’ (Booister 2009: 73). In the election campaign, it seemed that among the supporters of the party were also people from a non-Dutch background (Booister 2009: 118, 125).

The entrée of Fortuyn and Liveable Rotterdam, and especially the expectation that they would do well during the elections, made the electoral campaign fierce and harsh. Fortuyn and his political opponents often clashed hard and personally. Many opponents believed Fortuyn was a racist due to his proposal to abolish the ban on discrimination from the Dutch Constitution and to close the border for Muslim immigrants. In the last months before the election, when the polls indicated that Liveable Rotterdam could look forward to substantial electoral success, the election campaign became grimmer. The mainstream parties in Rotterdam, which were still taken somewhat by surprise by Fortuyn’s active role in Liveable Rotterdam, heavily opposed Fortuyn and rejected his call for restrictions on immigration and critique on Islam and the multicultural society. A number of Rotterdam organisations even lodged a complaint against Fortuyn for discrimination. Several national politicians, when talking about Fortuyn, referred to the Second World War and ‘the diary of Anne Frank’ (Booister 2009: 108). In Rotterdam, a Liberal Democratic Party councilman complimented the organisations that filed a complaint against Fortuyn for discrimination (Oosthoek 2005 32–33) and the Green Party leader talked about ‘deportations’ when talking about Fortuyn (Booister 2009: 107). Both the Labour Party leader and the Liberal Party leader labelled Liveable Rotterdam as an ‘extreme right’ party.

In the streets, there were people who supported Fortuyn, but others harassed him and called him the ‘Dutch Haider’ (referring to the leader of the right-wing Austrian Freedom Party (e.g. Oosthoek 2005: 100)). According to Sørensen, insults and threats by email increased. After an incident on the city’s south bank, where Fortuyn was harassed by a small group of young people from a non-Dutch origin, Liveable Rotterdam decided to stop campaigning on the street. The Liberal Party leader labelled Fortuyn a ‘spreader of hate’. Manuel Kneepkens from the City Party called him a ‘Polder Mussolini’ and compared him and his party with fascism on several occasions. Other (national) political party leaders also compared Liveable Rotterdam to extreme right parties. On top of that, the Labour Party, Christian Democratic Party, and the Liberal Party in Rotterdam refused to talk with Fortuyn about a coalition after the elections. According to the local newspaper, in one of the last political debates between the party leaders before the election, the debaters (Fortuyn and his opponents) avoided each other ‘as if contagious diseases can be transmitted’ (RD 4/3/2002).

-

Can Fortuyn be considered a populist?

-

The concept of populism is debated within the scientific literature. The concept nevertheless seems to have some core aspects most authors agree on: a reference to ‘the people’ and an anti-elite attitude, defending the man in the street or ‘the underdog’ (Canovan 1981: 294–297). These characteristics reappear in recent, popular, definitions of populism such as: “an ideology which puts virtuous and homogeneous people against a set of elites and dangerous ‘others’ who are together depicted as depriving (or attempting to deprive) the sovereign people of their rights, values, prosperity, identity and voice” (Albertazzi and McDonnell 2014: 3). This resembles the definition given by Mudde as: “an ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic groups, ‘the pure people’ versus ‘the corrupt elite’, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people” (Mudde 2004: 562, 2007). Within populism ‘the people’ is usually seen as a unity, indivisible and ‘good’ (Zaslove 2008: 322). Populists place the ‘good people’ against a corrupt elite, which leads to a firm ‘us versus them’ paradigm (Stanley 2008; Taggart 2000). Populists also turn against what they perceive as ‘dangerous others’ (Albertazzi and McDonnell 2014: 6). Whereas the elite is mainly an internal threat, the ‘dangerous others’ are external threats. These can be different groups such as immigrants, feminists and ecologists (Mudde 2007: 64–78; Zaslove 2008).

-

In general, Dutch scholars consider Fortuyn to be a populist (Koole 2010; Lucardie and Voerman 2012), and also regard his national party/list as such (Lucardie 2010; De Lange and Rooduijn 2011; Van Kessel 2015). To support that claim, these authors base themselves on the previous mentioned core criteria of populism, even though different scholars use different definitions and some use additional criteria. With a closer look, Fortuyn seems to fulfil the anti-elitist criteria more than the reference to ‘the people’ (Vossen 2013). This is certainly true in the Rotterdam case, where his anti-establishment attitude was a core aspect of his electoral campaign. Based on Taguieff (2002 in Te Velde 2010: 247) Fortuyn can at least be labelled a protest populist. Protest populists mainly focus on the anti-elitist factor, thus the enemy from above; the identity populists mainly focus on the people and identity, thus the enemy from outside. His attitude against the Islam falls nevertheless in the latter category.Footnote 3

4 Liveable Rotterdam in Power 2002–2006: Dealing with Superdiversity

The exact size of Liveable Rotterdam’s victory took everyone by surprise. The newcomer achieved more than one third of the Rotterdam vote, all major existing parties lost seats, and Liveable Rotterdam replaced the Labour Party as largest party.

After the initial shock, the existing parties upheld the unwritten rule that the largest party should take the initiative for coalition negotiations. And after a troublesome start, this led fairly quickly to a coalition between Liveable Rotterdam, the Liberal Party, and the Christian Democratic Party. Some reasons for this rapid agreement are that despite the aversion, Liveable Rotterdam’s priority of safety, was shared by most other parties in Rotterdam. And despite hard personal reprimands, the leaders of the different parties meet each other a couple of times during the campaign. The willingness of Fortuyn to give each coalition partner two aldermen positions in the new executive and his own party only three (a balance which did not resemble the electoral result) helped them to overcome their objections. Regarding content, there was enough to work with between the three parties. The Christian Democratic Party recognized itself in Fortuyn’s ideas on norms and values and the Liberal Party related to the desired attention for public safety and a more liberal economic policy.

When the new coalition was being formed, the media focused on Rotterdam intensively. It seemed that everyone was curious to find out how Fortuyn’s viewpoints would turn out in this first ‘test case’ of governing responsibility. People especially focused on Fortuyn’s controversial stands on immigration, integration, and Islam. It was thus to some a surprise that the two political coalition documents that appeared in 2002 were rather quiet regarding those themes. Both documents mainly focused on the word ‘respect’ in the way that people should behave towards each other, a compromise between Liveable Rotterdam and the Christian Democratic Party (Van Schendelen 2003: 258). The executive programme contained concrete measures to enhance social cohesion and to get citizens actively involved in their community. These projects were not always voluntarily, but nevertheless did not seem to resemble Fortuyn’s strong stands on the subjects of immigration, integration, and Islam (Rotterdam 2002: 33).

Addressing issues such as integration or Islam more directly after 2002 initially took place mainly ad-hoc. Several Liveable Rotterdam councilmen or aldermen made remarks or proposed ideas that included the obligation to speak Dutch in mosques, installing a maximum height for minarets on mosques, or to prohibit speaking Turkish or Moroccan in municipal services (interview service director). Such remarks, however, seldom led to policy changes, and over the years this led to unease among members of Liveable Rotterdam. Fortuyn at that moment was no longer present. He had been murdered in May 2002, shortly after the formation of the political coalition, causing a huge outbreak of protest in grief, in the Netherlands, but certainly also in Rotterdam.Footnote 4 Marco Pastors, one of the Liveable Rotterdam aldermen informally and later formally took over the party’s leadership. He formulated the unease of the initial silence about integration themes:

You cannot sit in a representative body with seventeen of Pim Fortuyn’s seats and then do nothing about integration. (Pastors 2006: 73)

The silence lasted until 2003, when the municipal research agency released a report that predicted that the overwhelming majority of certain areas in Rotterdam in 2017 would consist of people from a non-Dutch background (COS 2003). The first response to this report, surprisingly, came from a Labour Party member. A district alderman used it to publicly address the socioeconomic problems in his district and said that the city should mandate a maximum number of disadvantaged newcomers entering the city (RD 1/8/2003). This district alderman separated the socioeconomic situation from ethnicity. Liveable Rotterdam, entering the debate, did not. Alderman Pastors opted for a moratorium on immigration by ‘disadvantaged people from a foreign origin’ (RD 22/8/2003). This quickly led to a public discussion focusing on whether or not there should be a maximum of people from foreign origin in the city. According to a national news network survey, a majority of Rotterdam inhabitants was in favour of such a limit (RTL 23/8/2003). The executive responded by installing a committee to develop a report to understand what the demographic development noted by the Rotterdam research agency entailed for the city. The report appeared in December 2003 and was called ‘Rotterdam Presses On: The Way to a Balanced City’ (Rotterdam Zet Door. Op weg naar een stad in balans (Rotterdam 2003)). It contained proposals combining measures regarding migration, settlement, and integration. Some of the measures stirred controversy, especially the requirement that a person must earn 120% of the minimum wage to settle in certain Rotterdam neighbourhoods. Besides such repressive measures, there were also preventive measures such as ‘Welcome to Rotterdam’ (Welkom in Rotterdam), a project that tried to introduce new Rotterdam inhabitants to the city by connecting them with settled Rotterdam citizens. Another proposal was to provide subsidies for entrepreneurs who decided to start a business in one of the more disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

From this moment on, the topic of integration and Islam remained on Rotterdam’s public agenda. In 2005, Rotterdam organised the ‘Islam Debates’ (Islamdebatten), eight public gatherings about the role of the Islam. The debates dealt with themes such as the role of women, homosexuality, separation between church and state, education, and the economic situation. Liveable Rotterdam, more specifically alderman Pastors, used these debates to define his role of Islam critic. During the first Islam debate, Pastors and faction chairman Sørensen defended the statement: ‘the fear of Muslims is justified’. Other politicians at the debate and the overwhelming part of the visitors opposed that statement. According to Pastors, most other politicians did not dare to address problems surrounding the integration of immigrants. By that time, Pastors’ opinion on this topic was well known. In 2003, he wanted no more new immigrants to enter Rotterdam and in the beginning of 2005, he warned that Islamic law might be implemented in some Rotterdam districts if Islamic parties with ‘some idiots of the Green Party’ come to power. In November 2005, Pastors was quoted talking about the fact that Muslims often use their religion as an excuse for criminal behaviour. It reached the local press. Liveable Rotterdam’s coalition partner the Christian Democratic Party now lost confidence in Pastors. This meant that there was a majority in the municipal council to support a vote of no confidence and Pastors was forced to resign as alderman. Pastors later that same evening declared on national TV that he was the victim of ‘old politics’. According to him, the affair showed that it was still impossible to talk freely about all subjects even when there was support among citizens to do so. A few weeks later, when Pastors was officially elected as Liveable Rotterdam leader for the 2006 municipal council election, he repeated this message:

The last couple of weeks showed we are still needed. While other parties in Rotterdam politics now for years have talked about the fact that … the taboo on talking about integration and Islam has disappeared, they showed, with exception of the Liberal Party that the taboo as well as old politics is still there. (Liveable Rotterdam 2005)

Most people expected that the Labour Party would achieve a good result in the Rotterdam local election. The party was nationally doing well in the polls. And it achieved a large victory indeed, receiving more than 37% of the Rotterdam vote. Liveable Rotterdam became the second largest party with almost 30% of the votes. ‘A good result, but not good enough’, was the reaction of Liveable Rotterdam leader Pastors, thereby also referring to the result of the Labour Party. According to the media, it were for a large part ethnic votes that contributed to the victory of the Labour Party, implying that there was a clear division between the preference of Dutch and non-Dutch voters.

5 The Ethnic Vote in Rotterdam 1998–2014

In the Netherlands, non-Dutch residents can, in general, vote for the local elections if they have been living legally in the Netherlands for at least 5 years. In 1986, ethnic minorities were able to cast their vote for the first time. The turnout among them was (relatively) high, see Table 5.2. After that, turnout decreased. In 1998, turnout increased, probably as a response to the high support for the extreme right parties in 1994 (Van den Bent 2010: 286).

In a 1998 survey, it turned out that ethnic minorities in Rotterdam in general vote for either the Labour Party or the Green Party (Berger et al. 2001: 14). Among Turkish people, the Christian Democratic Party was also popular, but this probably had to do with the popularity of a specific Turkish candidate (Berger et al. 2001: 13). In 2002, turnout among ethnic minorities increased. The political programme of Liveable Rotterdam and especially (inter)views of Fortuyn might be the reason for this, but researchers have not been able to establish a direct link (see Table 5.3).

In 2006, turnout among ethnic minorities further increased. National influence probably played a role in this increase, e.g. the state secretary for integration that with her stern stances on integration attracted many supporters, but also many adversaries. However, research also pointed out that the foreign originated middle-class in Rotterdam held the opinion that local politicians should give a good example and not distinguish between Dutch people and people from foreign origin, something that they in their view did too often (Van den Bent 2010: 286, 255). This time, researchers also established a link between the ethnicity of the voter and the vote for Liveable Rotterdam: in neighbourhoods with more voters from a foreign origin, the percentage of people that voted for Liveable Rotterdam was lower (see Table 5.3). For 2010 and 2014, such conclusions are not available, but researchers pointed out that the electorate for Liveable Rotterdam since 2006 has been relatively stable (COS 2010; OBI 2014).

The profile of the Labour Party had already been clearer from the start. Even though information about ethnicity is not available for the 2002 election, researchers point out that the Labour Party in the elections of 2006, 2010, and 2014 received more votes in neighbourhoods with many people from a foreign origin. In 2006, more than one third of the extra votes can be traced back to votes for Turkish and Moroccan Labour Party candidates (COS 2010: 21). The researchers also note a strong correlation between the ethnicity of a candidate and that of the voters on neighbourhood level. In other words “Turks vote en masse for Turkish candidates and Moroccans vote en masse for Moroccan candidates” (COS 2010: 18). In 2006, the Labour Party had 5 Turkish candidates together achieving more than 13,000 votes and 4 Moroccan candidates receiving 8300 votes. In 2010, the Labour Party had 4 Turkish candidates with more than 13,200 votes and 3 Moroccan candidates with over 6200 votes (COS 2010: 21). This is about 9% of all Rotterdam votes.

In 2010 and 2014, the Labour Party lost many votes (see Table 5.4). On both occasions, for a substantial part due to the loss in votes from people from a foreign origin (COS 2010; OBI 2014). In 2010, almost half of the loss can be traced back to fewer votes for Turkish and Moroccan candidates (COS 2010: 21). In 2014, paradoxically, the Labour Party in Rotterdam received many votes in neighbourhoods with many voters from foreign origin, but has also faced its largest losses in those neighbourhoods (OBI 2014: 18–19). The lost votes mainly went to two parties: the Socialist Party (that won three seats compared to 2010) and a new party. NIDA Rotterdam, an Islamic party that won two seats in the municipal council.Footnote 5 While politically, NIDA opposes, among others, Liveable Rotterdam, electorally it turned out competition for the Labour Party. In neighbourhoods with the most people from foreign origin, the loss of the Labour Party compared to 2010 was the largest. And in several cases, Labour Party’s loss was NIDA’s win: the percentage voters for NIDA relates to the number of foreign people in a neighbourhood (R2 = 0.80) and the percentage of low incomes (0.60) (OBI 2014).Footnote 6 In 2018, the Labour Party loses more votes, NIDA again manages to win two seats, and DENK, an Islamic party already present in Dutch national parliament, wins four seats. The Freedom Party (the party of Geert Wilders) enters Rotterdam municipal council with one seat (Table 5.1).

6 Dealing with Superdiversity After 2006/The Labour Party Back in Power

After the 2006 election, Liveable Rotterdam and its former coalition partners did not possess a majority in the municipal council anymore. Another coalition therefore needed to be formed. This became a coalition with the Labour Party but without Liveable Rotterdam. The Labour Party however did not turn back all changes made in the previous years.

In the years before the Labour Party’s return to power, problems regarding the multicultural society were more publicly discussed and in some cases this led to policy (change). This was not limited to Rotterdam, but the Rotterdam executive with Liveable Rotterdam certainly had a frontrunner role. Apart from the Islamic debates and Rotterdam Presses On, criminal behaviour among certain ethnic groups was discussed more openly. For instance, problems regarding Antillean immigrants was the explicit topic of a Rotterdam conference in January 2006.

Approaching the new elections of 2006, media frequently asked (Rotterdam) citizens’ opinions. In Rotterdam there was support for a fiercer stand regarding integration and immigrants. From the Rotterdam voters, 62% agreed that it is regrettable that mosques increasingly dominate the street image (among Labour Party voters this support was 52%; among Liveable Rotterdam voters 82%). And a large majority, also from Labour Party voters, supported the statement that ‘criminal Antilleans should be deported’.

For the Labour Party, the electoral result of Liveable Rotterdam in 2002 was not only an expression of views it opposed. Some party members later called it a ‘wake up call’. They believed that views and problems, also related to Rotterdam’s superdiversity, were not to be ignored or trivialised anymore. A new party leader was one of the authors of a pamphlet in 2004 stating that:

The decrease of trust in government affected our party more than other parties. For many Rotterdam citizens the Labour Party was the face of government. Was the Labour Party not responsible for …. [among others] the insufficient integration of newcomers? The voters have punished us for this. And we have learned our lesson. (Labour Party 2004)

He and other Labour Party councilmen chose a strategy of not disapproving everything the Liveable Rotterdam executive proposed. Sometimes that also led to controversy when for instance the Labour Party leader “was attacked by the Cape Verdean community after the Labour Party released a report about sexual intimidation and incest within that community” (Volkskrant 8/5/2006). In the 2004 pamphlet, the Labour Party also clearly stated that groups such as young Moroccan and Antilleans people were overrepresented in crime statistics and it proposed stricter rules for immigration of young Antilleans and also that Antilleans already in Rotterdam should be registered (Labour Party 2004). For the 2006 election, a new Rotterdam Labour Party leader received this advice from his national party leader:

Choose exactly the same themes as Liveable [Rotterdam]. And do not campaign against the current executive policy. Say we will do the same, only much better. (RD 4/4/2005)

After the election, the Labour Party interpreted the election result as a dual assignment. The executive established a ‘social programme’ (sociaal programma) to make it clear that apart from continuing former executive policy the executive also wanted to improve the city mainly with more focus on social themes, such as improving employment, education, and social cohesion.

We face a large challenge. In some neighbourhoods over 40% of the working population is unemployed and over 15% depends on welfare... In many Rotterdam neighbourhoods more than 60% of the people have low to very low education. Too many Rotterdam inhabitants do not speak the language well enough. (Rotterdam 2006b: 9)

The executive regarded improving these statistics as the main challenge for its social programme. The social programme was aimed to improve the ‘weakest’ in society whose lives, according to one alderman, had not been improved under the former executive (interview). The executive announced that everyone should participate and no one would be left behind. It proclaimed that Rotterdam would once again be a city ‘where everyone counts’, and where all work ‘together towards a non-divided city’ (NRT 2006).

Nothing but positivity is coming from [City Hall]. [Alderman] Kaya (Green Party) believes that the gap between people from Dutch origin and people from foreign origin… will be somewhat more closed. Alderman Kriens (Labour Party) refuses even to think in those categories: ‘The gap for us is interpreted as between people who participate and people who keep other people from participating’. (Trouw 19/9/2006)

It quickly turned out that the executive, apart from its social programme to help the most needy, also continued taking a tough stance towards people that in the executive’s view ‘limit other people to participate’. This stance, developed under the previous executive legislature, is described as entailing a series of changes in common views of social issues … This approach was demonstrated through plans and projects. The 2006 coalition accord uses phrases such as ‘establishing clear borders’, ‘reciprocity’, and ‘firmly address people’ who ‘pass on opportunities’ (Rotterdam 2006a: 2). Such rhetoric and the desire to help people go hand in hand (Rotterdam 2006a: 4–11), also regarding integration.

From its start, the executive indicated that it would stop using the word ‘integration’. Instead, it promoted the word ‘participation’ to indicate that everyone should be included, with no distinction between groups of people (such as people from Dutch or foreign origin).

In the beginning of 2007, the executive and alderman Kaya (Green Party) presented a more elaborated vision on ‘participation’ in the report ‘City Citizenship: the motto is participation’ (Stadsburgerschap: het motto is meedoen). The report consists of five themes: city pride, reciprocity, identity, participation, and establishment of behavioural norms. The report emphasises the importance of participation in society and stresses that every inhabitant has duties as well as rights, such as ‘to use Dutch as the common language’ and to uphold Western values such as the equality of men and women, hetero- and homosexuals, believers and non-believers, and not to accept honour killing, or female circumcision’ (Rotterdam 2007: 6–7). The media noted that that the City Citizenship report contained several points the former executive had raised and alderman Kaya, at that time councilmen for the Green Party, had called discriminating (Parool 2007). Personal aides of alderman Kaya acknowledged that his vision was not that much different from that of his Liveable Rotterdam predecessor (interview). And even though words such as ‘ethnicity’ and ‘integration’ were avoided in the City Citizenship report, they were more evident in other aspects of executive policy. In 2008, following the Antillean Approach, a ‘Moroccan Approach’ was created to decrease the high rate of recidivism among Moroccans. This approach provides family coaches, homework assistants and a ‘case manager’ for several young Moroccans to help them find jobs, internships, and housing (Rotterdam 2009: 63–64). Later, also problems with Poles were discussed openly.

7 Concluding Remarks

The case of Liveable Rotterdam is interesting because it shows the sudden rise of a new protest populist party and the disruption it can cause to a relatively stable political landscape. It also shows how it can accomplish change.

The political change that took place in 2002 regarding integration and superdiversity was first and foremost a change in style and the way Rotterdam government and the executive dealt with integration problems. Fortuyn, party founder Sørensen, and alderman Pastors were very sceptical about the benefits of superdiversity and at the very least wanted to discuss related problems in the open. Their stances on integration often stirred controversy. They however did not always lead to policy changes. And when it did, this went slower and the results were often less ‘harsh’ than the initial proposals. For policy change, Liveable Rotterdam had to depend on others. In a consensual system such as in the Netherlands, it takes time to build the necessary coalitions, to persuade former adversaries, make compromises, and so on. And regarding integration, it was especially Liveable Rotterdam’s coalition partner the Christian Democratic Party that countered Liveable Rotterdam on several occasions, eventually also supporting a vote of no confidence, leading to Pastors’ dismissal. The changes that did succeed could generally count on broader support than only from the Liveable Rotterdam politicians. And this was important in 2006 when the Labour Party returned to power. In 2006, the first noteworthy change was the style of the new executive. It wanted to make no distinction between groups of people. However, there was policy continuity as well (just as there had been in 2002). Especially the obligations connected to being part of Rotterdam society such as to use Dutch as common language and to uphold Western values such as the equality of men and women, hetero- and homosexuals, believers and non-believer were strongly maintained. This continuity came forth from the belief of several Labour politicians thought/decided that some proposals originating from Liveable Rotterdam were not as bad as they had initially judged them to be, and – related to that point – from the electoral results. Both the elections of 2002 and 2006 showed that Liveable Rotterdam with its attention for the problems of integration had the support of a large part of the Rotterdam electorate – support that remains until this day. And in 2014, Liveable Rotterdam once again became part of the governing coalition. In 2006, the general feeling among most parties was that such problems should not be ignored as the Labour Party more or less did during the electoral campaign in 2002. When the Labour Party returned to power in 2006 it wanted to put this lesson in practice. This meant that on the one hand it wanted to implement policy its electorate expected: attention for the weaker in society. On the other hand, the Labour Party maintained some of the changes of the previous executive as it acknowledged the worries of a large part of the Rotterdam electorate as well.

Notes

- 1.

The municipal council nominates a candidate for mayor. National government in general will accept that preference.

- 2.

The election programme of Liveable Rotterdam included other themes as well, such as investment in education (especially personnel), requiring that Dutch becomes the main language in all Rotterdam schools, and creating more green spaces. The party was against the privatisation of the Harbour Company and the Public Transport Service, but it did want the Harbour Company to function more as a business and to stimulate more competition between companies in the harbour. The party wanted the Tweede Maasvlakte (a large extension of the harbour) to be developed immediately. Liveable Rotterdam was in favour of more night flights to and from Rotterdam airport. It felt that entrepreneurs and businesses should be supported, meaning, among other things, more subsidies and less bureaucracy. The party preferred building or renovating expensive houses to attract the richer part of the population [no mentioning of mixing people, JvO]. The party also supported the return of the ‘human measurement’ in culture policy, meaning among other things more investment in people and less in buildings and concrete (Liveable Rotterdam 2002).

- 3.

Several authors also have argued that populism in the Netherlands was present before 2002 and that Fortuyn was not the first politician or party leader with a populist style. In the 1990s, the extreme right parties and the Socialist Parties – both elected in the Rotterdam municipal council – were to some extent considered populist (e.g. Lucardie and Voerman 2012).

- 4.

The Parliamentary election was only 9 days after the murder. Fortuyn’s national list of candidates without its leader received 17% of the Dutch vote, making it the second largest national party.

- 5.

Islamic parties were not new. E.g. in 1998, 6% of Moroccans voted for the Islamic Party (Berger et al. 2001: 13).

- 6.

The loss of Labour Party votes in Rotterdam in 2010 and 2014 is in line with the result in other Dutch municipalities. On average, the Labour Party nationally achieved 24% of the votes in 2006, 16% in 2010, and 10% in 2014.

References

Albertazzi, D., & McDonnell, D. (2014). Twenty-first century populism: The spectre of Western European democracy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Berger, M., Fennema, M., van Heelsum, A., Tillie, J., & Wolff, R. (2001). Politieke participatie van etnische minderheden in vier steden. Amsterdam: Institute for Migration & Ethnic Studies (IMES).

Booister, J. (2009). Clash aan de Coolsingel: de wegbereiders van Pim Fortuyn. Soesterberg: Uitgeverij Aspekt B.V.

Bouwmeester, H. (2000). Ruimte voor de economie: dertig jaar ontwikkelen van Rotterdam. Samson: Alphen aan de Rijn.

Canovan, M. (1981). Populism. New York: Harcourt Brace Javonovich.

Chorus, J., & de Galan, M. (2002). In de ban van Fortuyn: reconstructie van een politieke aardschok. Amsterdam: Olympus.

COS: Rotterdam research agency. (2002). Analyse Gemeenteraadsverkiezingen Rotterdam. 6 maart 2002. Rotterdam: Centrum voor Onderzoek en Statistiek (COS).

COS: Rotterdam research agency. (2003). Prognose Bevolkingsgroepen 2017. Rotterdam: Centrum voor Onderzoek en Statistiek (COS).

COS: Rotterdam research agency. (2006). Analyse Gemeenteraadsverkiezingen 2006. Rotterdam: Centrum voor Onderzoek en Statistiek (COS).

COS: Rotterdam research agency. (2010). Analyse Gemeenteraadsverkiezingen 2010. Rotterdam: Centrum voor Onderzoek en Statistiek (COS).

De Lange, S. L., & Rooduijn, M. (2011). Een Populistische Tijdgeest in Nederland? Een Inhoudsanalyse Van De Verkiezingsprogramma’s Van Politieke Partijen. In R. Andeweg & J. Thomassen (Eds.), Democratie Doorgelicht (pp. 319–334). Leiden: Leiden University Press.

Dekker, J., & Senstius, B. (2001). De tafel van Spruit: een multiculturele safari in Rotterdam. Alphen aan de Rijn: Haasbeek.

Fortuyn, W. S. P. (1997). Tegen de Islamisering van onze cultuur. Utrecht: Uitgeverij A.W. Bruna.

Koole, R. (2010) Populisme en politieke legitimiteit in Nederland. In Vereniging van Griffiers, Het huis van de democratie na de gemeenteraadsverkiezingen: achterstallig onderhoud? (pp. 44–54). Den Haag: Sdu Uitgevers.

Labour Party. (2002). De PvdA en Rotterdam: living apart together? Rapport van de commissie Aubert naar aanleiding van de verkiezingsnederlaag van maart 2002.

Labour Party. (2004). Blijvend veilig Rotterdam, publication from Labour Party faction, written by Cremers, B., Kriens, J., Van der Meer, S.

Linthorst, M. (2004). De Partij van de Arbeid in Rotterdam: beschouwingen van een betrokken buitenstaander. In F. Becker, W. van Hennekeler, M. Sie Dhian Ho, & B. Tromp (Eds.), Rotterdam: het vijfentwintigste jaarboek voor het democratisch socialisme (pp. 208–218). Alphen aan de Rijn: Haasbeek.

Liveable Rotterdam. (2002). Leidraad, election programme of Liveable Rotterdam.

Liveable Rotterdam. (2005). Speech of Marco Pastors when elected as Liveable Rotterdam leader on 23/11/2005, published on www.leefbaarrotterdam.nl, consulted on 4/4/2006.

Lucardie, P. (2010). Tussen establishment en extremisme: populistische partijen in Nederland en Vlaanderen. Res Publica, 2, 149–172.

Lucardie, P., & Voerman, G. (2012). Populisten in de polder. Amsterdam: Boom.

Mudde, C. (2004). The populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 4, 541–563.

Mudde, C. (2007). Populist radical right parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

NRT. (2006). Nieuw Rotterdams Tij/Rotterdams Tij, Rotterdam municipal magazine, September 2006.

OBI: Rotterdam research agency. (2014). Analyse verkiezingen gemeenteraad en gebiedscommissies 2014. Rotterdam: Onderzoek en Business Intelligence (OBI).

Oosthoek, A. (2005). Pim Fortuyn en Rotterdam. Rotterdam: Uitgeverij Ad Donker B.V.

Parool; Dutch newspaper. (2007). Van de Fortuynrevolte rest alleen nog een standbeeld; ‘leefbaar light’ noemen ze het nieuwe college, 5/5/2007.

Pastors, M. (2006). Tot uw dienst: een politiek pamflet. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij van Praag.

RD. (2003a). We kunnen de problemen nu al niet meer aan. 1/8/2003.

RD. (2003b). Leefbaar wil limiet aan aantal nieuwkomers. 22/8/2003.

RD. (2005). Wouter Bos: ‘Kies dezelfde thema’s als Leefbaar’. 4/4/2005.

RD: Dutch newspaper. (2000). College erkent effect van inspraak niet zo te weten. 10/11/2000.

RD: Dutch newspaper. (2002). Afstand ook na debat groot tussen PvdA en Leefbaar Rotterdam. 4/4/2002.

Rotterdam. (1998a). Veelkleurige stad uitvoeringsprogramma 9. Executive document.

Rotterdam. (1998b). Effectief allochtonenbeleid. Rotterdam municipal service document.

Rotterdam. (2001). Woorden èn Daden. Een terugblik op de uitvoering van het Collegeprogramma 1998–2002. Executive document.

Rotterdam. (2002). Het nieuwe elan van Rotterdam …en zo gaan we dat doen. Collegeprogramma 2002–2006. Executive programme 2002–2006.

Rotterdam. (2003). Rotterdam zet door. Op weg naar een stad in balans.

Rotterdam. (2006a). Perspectief voor iedere Rotterdammer: coalitieakkoord 2006–2010. Political coalition document.

Rotterdam. (2006b). Rotterdam 2006–2010 “De stad van aanpakken. Voor een Rotterdams resultaat”. Executive programme 2006–2010.

Rotterdam. (2007). Stadsburgerschap: het motto is meedoen. Version 23/1/2007, document, not further specified.

Rotterdam. (2009). Safety index 2009. Municipal service document.

RTL: Dutch newsnetwork. (2003). Rotterdam juicht beperking allochtonen toe. Article on RTL website, www.rtl.nl, 23/8/2003.

Stanley, B. (2008). The thin ideology of populism. Journal of Political Ideologies, 1, 95–110.

Taggart, P. (2000). Populism. Buckingham: Open University Press.

te Velde, H. (2010). Van regentenmentaliteit tot populisme. Politieke tradities in Nederland. Amsterdam: Bert Bakker.

Trouw: Dutch newspaper. (2006). Rotterdam ademt positivisme. 19/9/2006.

van de Laar, P. (2000). Stad van Formaat: geschiedenis van Rotterdam in de negentiende en twintigste eeuw. Zwolle: Waanders Uitgevers.

van den Bent, E. A. G.. (2010). Proeftuin Rotterdam. Bestuurlijke maakbaarheid tussen 1975 en 2005 (Rotterdam as a testingground for governmental malleability between 1975 and 2005). PhD thesis, Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands)

Van Kessel, S. (2015). Populist parties in Europe. agents of discontent? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

van Ostaaijen, J. J. C. (2010). Aversion and accommodation: Political change and urban regime analysis in Dutch local government: Rotterdam 1998–2008. Delft: Eburon Academic Publishers.

van Praag, C. (2004). Rotterdam en zijn migranten. In F. Becker, W. van Hennekeler, M. Sie Dhian Ho, & B. Tromp (Eds.), Rotterdam: het vijfentwintigste jaarboek voor het democratisch socialisme (pp. 58–76). Alphen aan de Rijn: Haasbeek.

van Schendelen, R. (2003). ‘Katholieke’ of ‘protestantse’ coalitievorming? De formatie van het Rotterdamse college in 2002. Groningen: Documentatiecentrum Nederlandse Politieke Partijen.

Volkskrant. (2002). Fortuyn: grens dicht voor islamiet. 9/2/2002.

Volkskrant. (2006). Een ondankbare taak. 8/5/2006.

Vossen. (2013). Different flavours of populism in the Netherlands. In R. Stefano (Ed.), The new faces of populism. University of Rome.

Zaslove, A. (2008). Here to stay? Populism as a new party type. European Review, 3, 319–336.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

van Ostaaijen, J. (2019). Local Politics, Populism and Pim Fortuyn in Rotterdam. In: Scholten, P., Crul, M., van de Laar, P. (eds) Coming to Terms with Superdiversity. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96041-8_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96041-8_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-96040-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-96041-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)