Abstract

The specific characteristics of collective labor conflicts in Poland are related to the ownership structure of Polish companies. Frequently the company management is not a direct party in a conflict, rather it is the company owner, e.g. State Treasury (education, health care system), a parent company based overseas, or territorial self-governmental authorities (transport, water supply). This context often leads to stagnation and prevents conflict resolution. Apart from the structural problem, also the perception of the role of mediators is noteworthy. Parties may come to an agreement when choosing one, but afterwards it may result in applying for a mediator to be appointed by the Minister (to prevent either of the parties getting the feeling that “their own mediator” has been chosen). There are also

collective conflicts which are mediated by a local authority or someone considered as impartial.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

-

Case 1—Collective conflict in the Polish unit of an international company

-

In the Polish subsidiary of the company, the trade union has been rejecting management’s decisions for years. In this particular conflict, the union demanded a higher share in bonuses for line workers and a different meal plan. The management sought a mediator to help resolve the dispute since there was an imminent threat of a strike. At first, the mediator had a meeting with the management, an HR department employee and a lawyer, with the aim of collecting information about their negotiating position. Then, the mediator met the trade union representatives also in order to gather information regarding their negotiating position. Both parties’ positions and their individual expectations were very divergent. Negotiators were chosen, and legal, economic and HR arguments were prepared. The parties were trained for multi-stage negotiations. After this process, the strike alert was cancelled, a settlement was reached and a collective agreement was signed.

-

Case 2—The bus drivers’ strike

-

Mediation can be undertaken by various persons, and a bus drivers’ strike in the Municipal Transportation Company in Kielce in August 2007 may serve as an interesting example. As a result of the failure to reach an agreement with the City Mayor, the crew of the Municipal Transportation Company went on to strike under the motto of “Stop privatization at the workers’ expense”. Having the prospect of a takeover of the company by an international organization (Veolia Transport Polska), the workers demanded to be guaranteed a package of social services, including employment security, decent pay and the modernization of the bus fleet. On the eighteenth day they reached an agreement, the municipal transport company was converted into an employee-owned company and was guaranteed the monopoly of Kielce’s public transportation. The mediation was undertaken by a local bishop who got engaged in solving the conflict in the face of previous failures (Sieczkowski; Sukces biskupiej mediacji, strajk MPK zakończony; Wach, 2007).

1 Introduction

The specific characteristics of collective labor conflicts in Poland are related to the ownership structure of Polish companies. Frequently the company management is not a direct party in a conflict, rather it is the company owner, e.g. State Treasury (education, health care system), a parent company based overseas, or territorial self-governmental authorities (transport, water supply). This context often leads to stagnation and prevents conflict resolution. Apart from the structural problem, also the perception of the role of mediators is noteworthy. Parties may come to an agreement when choosing one, but afterwards it may result in applying for a mediator to be appointed by the Minister (to prevent either of the parties getting the feeling that “their own mediator” has been chosen). There are also collective conflicts which are mediated by a local authority or someone considered as impartial.

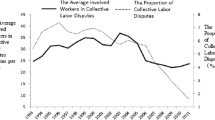

The Central Statistical Office of PolandFootnote 1 published another edition of the Yearbook of Labor Statistics in March 2016. Additionally, recent reports of the Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Policy show the data on mediation in collective conflicts. Reports indicate that the National Labor Inspectorate registered 1698 collective conflicts between the years 2014 and 2016. Most cases were registered in Mazowieckie and Śląskie Voivodships, in such branches as industrial processing, health care, social assistance, production of energy, mining and exploration, and the transport industry (Statistical Yearbook of Labor, 2015). Of these 1998 cases of collective conflicts, only 211 used mediations and/or facilitated negotiations.

On the other hand, during this period only 23 cases collective conflicts were finished after the negotiation stage and the parties signed an agreement after negotiations (that is, before mediation). This means that ca. 1, 5% of the collective conflicts ended in agreement after negotiations. At the same time, in a high percentage of cases (188 cases, 11%) the parties didn’t agree and strived for a strike, so they were forced to try mediation. The disparity in between the registered collective conflicts and those which ended after negotiations may suggest that the majority of conflicts remain in suspension (2014—187; 2015—1096; 2016—181), despite not going to strike or reaching an agreement. This situation, considering the persistent lack of agreements between conflicting sides, poses the threat of recurrent collective conflicts in the future, as issues seem to have not been fully solved.

Social dialogue in Poland is closely related to its history, the period of social and economic transformation, the post-socialist legacy and the structure of the system of trade unions (Kożusznik & Polak, 2015, 2016). The unions are the second biggest community of the non-profit sector in Poland (after the Roman Catholic Church). Currently, there are approximately 20,000 trade union organizations registered in Poland, of which about 60% are active. Meanwhile, the level of unionization according to recent data is at 5–11%,Footnote 2 which is one of the lowest in the EU (Feliksiak, 2017; Goś-Wójcicka & Sekuła, 2015).

The system for managing collective conflicts in Poland was established May 23, 1991 with the Act on Resolution of Collective Disputes.Footnote 3 Under this Act, a collective dispute between workers and an employer may refer to (1) working conditions, (2) pay, (3) social benefits, (4) trade union rights, or (5) freedoms of workers. Thus, the Act includes a number of specifications of general topics falling within the legal definition of a collective conflict. It is not permitted to manage an individual workers’ demand as a collective dispute if it’s feasible to process it through a body for resolving workers’ claims (a labor tribunal). It also means that all industrial actions regarding the reorganization of a company, its development, policy, ownership changes, management structure, the election of authorities, to name a few, cannot be the subject of a collective conflict in the eyes of the Act.

Here is an example of a real conflict which was not considered currently applicable to the statutory regulations as it didn’t fall within the legal regulations.

-

Case 3—The reorganization of a big Polish company

-

A collective conflict occurred in one department of a big company. The workers were deeply displeased with a decision about the reorganization of their department, a decision made by the previous management and executed by the current management. This decision entailed the transfer of the unit to another city. Even though it meant a significant change in the working conditions, following the Act on Resolution of Collective Disputes, the situation was not qualified as a collective conflict. This meant that the statutory regulation mechanisms were not applied in this case. The employees were transferred but remained deeply regretful, lost their trust in the management and were left with the conflict which remains unsolved…

At the same time, if the conflict issue results from a collective labor agreement or any other agreement in which a trade union has participated, then such an agreement should be previously terminated by a dismissal notice. The wording of these provisions causes a number of issues to not be covered by the statutory definition which in fact constitute causes of collective conflicts are, and consequently they are excluded from the scope of this legal regulation.

In the Polish studies conducted within the project covered in this handbook, most respondents indicated the limitations of the Act’s provisions while they simultaneously emphasized the need to implement changes to existing regulations in Poland so as to include the actual diversity of collective conflicts (e.g. in a situation of a company’s restructuring, ownership changes, providing an employment guarantee or redundancy packages for employees).

Parties in a collective conflict are workers—represented by a trade union- and an employer or employers who are represented by an employers’ organization (Kurzynska, 2008). Within the meaning of the Act, as referred to in article 3 of the Labor Code, an employer can be an entity, i.e. an organizational unit (also an entity without legal personality), or a physical person if they employ other workers. In organizations where there is more than one trade union organization, each trade union is entitled to represent their interests in collective conflicts. In the event of a lack of unions in a company, the Act provides that “on behalf of workers in a workplace where a trade union is not acting, a collective dispute may be dealt by a trade union organization as requested by the workers to represent their collective interests.”

Under the Act on Resolution of Collective Disputes, mediation proceedings are obligatory, that is, they must be conducted following a negotiation deadlock if employees’ are calling a strike. This means that the mediation proceedings must always precede the announcement of a strike decision. The obligatory nature of mediation is perceived by most of the research participants as a weakness of the Polish system. Experts emphasize that a number of disputes are subject to mediation without the aim of reaching a real agreement, rather to avoid being accused of breaking the law in case of employers, and in case of the trade unions, to create an opportunity to undertake industrial actions such as strikes. One of the interviewed mediators said: “Mediations on the basis of the law are pretended, because mediations should be voluntary. Now, mediations are only the other element of the dispute; employers approve them because they want to obey the law and Labor unions because they want to strike”.

In accordance to the provisions of the Act, collective conflicts are managed through negotiations, mediations and arbitration proceedings. Negotiations, mediations and arbitration proceedings constitute separate stages of resolving collective disputes at work. A strike is considered a final attempt at settling a collective conflict in case of a lack of agreement between parties, as a tactic of employees to gain a better negotiation position. An alternative to strikes in the event of a mediation failure, is voluntary submission to the proceedings before social arbitration boards, which occurs very rarely in Poland. Recent data from 2014 confirms that proceedings before social arbitration boards in courts practically haven’t existed during the last decade.

2 Characteristics of the System

The Social Dialogue System in Poland in accordance with the spirit of multi-level governance system consists of the Social Dialogue Council as a national forum for tripartite dialogue. “The tripartite dialogue engages employee representatives, employers and the government in the discussion about public issues, projects of legal solutions and other decisions made concerning the interests of the employers and employees” (Social dialogue) (https://www.mpips.gov.pl/en/social-dialogue/). At the regional level are the Voivodship Social Dialogue Councils. Sectorial dialogue also presents the tripartite formula. Employees are represented by trade unions and councils of employees; employers are represented by an employers’ organization (Fig. 10.1).

Moreover, organizations associating mediators and social arbitration should be also indicated, though there’s a relatively low development level in Poland. On the other hand, at the level of social partners, there’s considerable fragmentation and political involvement of trade union organizations. Further, the system of the employers’ organizations is quite stable and there’s a relatively poorly developed system of mediators’ organizations for solving collective conflicts. The differentiation between court mediators and mediators in collective conflicts also contributes to citizens’ confusions about the system.

Our research confirmed that mediation is considered a mandatory stage of conflict which allows the workers’ side to proceed with a strike call. Strikes have been registered and monitored during the past years in Poland (Krajewska, 2018). Furthermore, also the number of conflicts has been reported, specifying those conflicts which, thanks to negotiations and mediation, were settled, or for which a report of divergences was signed and the case was brought before social arbitration (Lukawska, 2008). The statistics and publications prepared for social reporting and accounting are supplementary to scientific research, which presents a wider context of collective conflict resolution in Poland.

The interviews and studies conducted for the NEIRE III project present a more individualized approach for the parties in collective conflicts, as well as mediators and policy makers.

Figure 10.2 presents the process for collective conflicts from the start till the stage of strike or arbitration. A collective conflict ends after an agreement or a court settlement is signed, or it remains suspended. There is no time limit for these conflicts, that’s why many conflicts remain unsolved and/or suspended.

The Act on Resolution of Collective Disputes determines that a conflict is collective when requirements are met with regards to a larger community, a clash and its relation to work (Żołyński, 2013). Following such definition, a dispute is an example of a real conflict existing between employees and an employer. It is formed along with the aim of gaining improved conditions for workers (all workers or part of the workforce) and an employer who refuses to meet their demands. An employee representative stated: “The current system reinforces “artificial” local disputes. In fact the problem concerns all of the country—(e.g. the system of healthcare and education). The dispute at local level doesn’t solve the general problems”.

3 Characteristics of the Mediators and Third Party Procedures

Under the Act, formal mediation starts if a stage of negotiations has been completed and the party initiating a dispute maintains the claimed demand. The conflict is managed by a person who guarantees impartiality, who is referred to as a mediator. Polish legislators prescribes the so called Multi-Steps-ADR, a path from less formalized towards more formal conflict resolution procedures. The Act does not specify the participation of any independent/informal institutions as third parties, such as consultants.

3.1 Choosing a Mediator

The parties can establish the possibility of allowing the consultant to solve a conflict. If a mediator claims that the resolution of a collective conflict requires a detailed or additional fact relevant to the subject of a dispute, he notifies the parties of that. Moreover, if it is necessary to establish the economic and financial situation of a workplace in relation to the demands in a dispute, a mediator may propose an assessment to be made in such cases. The author of the assessment actually does not participate in the mediation process but provides relevant documents for it. The system also allows combining mediation with other alternative ways of solving collective conflicts. When a mediation is not successful and the party initiating the conflict will not use its right to strike, then that party can request a solution from the Board of Social Arbitration. The Board of Social Arbitration is composed of the chairman—a judge—and 3 members appointed by the parties. The industrial conflict is recognized by the board at a regional court dealing with cases in the scope of labor law and social insurance, and in the case of multi-employer industrial disputes, they are arbitrated by the Board of Social Arbitration at the Supreme Court.

The role of mediator may be taken by a person or a group of people. Some argue that it is better not to engage a single mediator who also for example conducts consulting activities, and prefer a collective body, such as a conciliation committee. However, in most cases of collective conflicts, the parties appoint one mediator. During the mediation period, mediators are entitled to take a leave off work (up to 30 days a year).

3.2 Remuneration

Remuneration cannot be lower than the amount specified in a regulation of a competent minister responsible for labor matters. A mediator is also entitled to have transport and accommodation costs reimbursed as per an agreement with parties to a collective conflict. It is to be noted, however, that the amounts prescribed as minimal are quite low in comparison to the hourly rate which may be obtained by lawyers, psychologists and other specialists. As our experts stressed, these amounts have not been indexed for over 10 years so the professional mediator position is not an attractive one.

The Act provides that only a mediator who is trusted by the parties may be the third party. The mediation concludes with an agreement signed by all parties (including the mediator), and finally, a mediator appointed by the minister (in case the parties cannot appoint one) may not be cancelled by the parties. They have to submit an application to the minister for doing so, while in other cases parties may cancel a mediator if he loses their trust. In the event of mediations which don’t end in agreement or only a partial agreement and a report of divergences, these actions are also accompanied by a mediator. Apart from that, there are no other protection mechanisms for a mediation process. Mediators acting as third parties should provide the mediation process in accordance with the so-called Working Standards for Mediators (Kawalec, 2009).

Since February the 5th, 2018, there are 206 mediators on the list of the Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Policy, broken down into individual voivodships.Footnote 4 The names of mediators associated in professional mediators’ associations are also available (there is no obligatory professional self-government of mediators in Poland). There is also a possibility to use the list of mediators accredited by employers’ organizations. The difference is that in general they act in disputes with business partners, and not only in collective disputes. The list of mediators is established by the minister competent for labor issues in consultation with trade union organizations and employers’ organizations. From the interviews we understand that this list is however not checked by parties or updated.

The above figures do not reflect a complete picture since every person who safeguards impartiality in the opinion of conflicting parties may become a mediator and such a person does not have to be on the list of registered mediators. The research participants, in particular from a group of policy makers, stressed the need to professionalize the position of a mediator in the near future. Up to date, the people acting as mediators did their work without the need to demonstrate their additional qualifications or experience.

A mediator is appointed by the parties in a particular case. If the parties do not reach an agreement regarding the choice of a mediator within 5 days, further proceedings are conducted with the participation of the indicated mediator, upon request of either party, from the minister’s list of mediators. No information is given as to how frequently this list is updated. Interviews with the mediators confirm that the list is out of date.

3.3 Appointment of Mediators

The act does not determine any specific requirements for a mediator. Thus, a mediator doesn’t have to possess particular professional qualifications, e.g. to be a lawyer or to complete a course or training in the area of mediation, although, undoubtedly, legal or economic knowledge or practical skills as to how to conduct mediation should be taken into account when selecting a mediator. The most important aspect is impartiality and the likelihood to be accepted by the parties. This person cannot be related to either of the parties nor to the people representing them, in such a manner that it could result in challenging this person’s impartiality.

Some mediators are partly associated to the chamber of mediators or arbitrators and to other professional associations. According to the current working standards set for mediators, they are required to raise their qualifications, but it should be treated not as a statutory requirement but only as a recommendation. Mediators have access to training, for example courses or post-diploma studies, which are organized by different organizations (universities, associations, foundations, ministry, etc.).

Our studies confirm that, as a general rule, mediators are people with legal, psychological, sociological or industry-specific education (medical, mining, technical etc.). The interviewed mediators had 20-years professional experience on average and 10-years’ experience conducting mediations. Mediators often hold managerial positions in trade union organizations or work in HR units of companies, and they can be employed by both private and public companies. When they act as mediators they get time off work and they carry out the mediation process according to the act or the contractual agreement. The observations supported the assumption that Polish mediators’ strength is based on their professional competences and expertise. However, the statutory authority of mediation is quite weak and therefore, sometimes conflicting parties do not take mediation and mediators seriously. Thus, in the respondents’ opinion, the professionalization of the role of the mediator in social conflicts should be provided in the near future.

4 Description of the Facilitation or Mediation Process

The findings confirm that every mediator uses his or her own strategy. Some of them start with meeting each party separately, then they organize a joint meeting during which they outline the causes and dynamics of the conflict, and then, they help parties reach a consensus. Other mediators stated that if they did not observe real willingness to reach an agreement by the parties, they would terminate the mediation process. Some mediators (especially with psychological background) pay special attention to the sources of the conflicts (e.g. a dispute over values, a dispute of interests, etc.) and attempt to transform their differences into perception issues since parties are more likely to find an agreement in these cases.

During every step of the mediation, including meetings, presentation of positions and exchanging of expectations, agreements and minutes should registered. This is done to document all evidential reasons in the event of being used in possible further legal proceedings. A mediator who works under an employment contract is entitled to be off work throughout the duration of the mediation process. During that period, a mediator is not entitled to receive his regular remuneration for his regular employment contract.

A remuneration condition for a mediator from the ministry’s list is laid down by the relevant regulation. On the other hand, mediators who are selected outside of the ministry’s list have their remuneration and reimbursement of travel and accommodation expenses regulated by an agreement between the parties. The regulations apply the principle that the mediation proceeding costs—which are composed of remuneration for a mediator and his travel and accommodation costs—are to be incurred by both parties in equal parts, unless a different division of costs is agreed. Additionally, there is the Workplace Card and the Collective Dispute Card for statistical purposes (for the Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Policy). An interviewed employer said: “the mediation system is very rarely used. The mediations don’t bring profit to the law offices, that’s why lawyers do not develop these forms of coping with collective conflicts. On the mediators list we find names of people who do not work as mediators”.

The parties may also withdraw the power of the selected mediator and choose another one at any time during the mediation process. This decision is at their own discretion. The Act regulates that in case of mediations conducted by a mediator from the ministry’s list, the parties cannot cancel him. Our study shows that it’s a common practice that one party indicates three candidates and the other one also puts forward three candidatures, and it occurs that the names of mediators are the same on both lists. Each party may refuse mediators proposed by the other party, ask for another mediator, or propose their own. Our findings confirmed that parties are more likely to request help from local authorities, rather than from a list of mediators. The mediator usually works individually. It is a matter of a mediator’s experience and depends on the nature of a dispute itself. There are also mediators working in pairs or in groups of three (e.g. bringing in a psychologist or a lawyer creates a possibility of invoking content-related specialists). However, in most cases there is one mediator, but if he fails to meet the expectations, then there is a change (e.g. if he was not suitable for solving conflicts in a given field—there is no information available in this respect).

4.1 Starting the Mediation

Mediation proceedings may be conducted according to the rules applicable at the negotiation phase. Thus, it is important that all actions are taken in good faith, respecting the interests of the parties in conflict, as well as respecting the interests of these workers who are not directly involved in the collective conflict. Mediators act under a general formula of mediations which includes the essence of mediation (impartiality and neutrality of a mediator, confidentiality, voluntary participation, monitoring of the content of an agreement by parties). There are individual rules for contacting parties to provide information about a meeting—by post, by phone, responding to additional enquiries. As a general rule, there is an individual kick-off meeting with each party and then, they have a joint meeting. Explanations are given about the mediation process (the so-called mediator’s monologue), and a favorable atmosphere is created.

4.2 The Mediation

The Act does not include specific solutions in respect of a mediator’s rights, however, as it results from the essence of mediation and existing residual regulations, such rights may be divided into three types: organizational, analytic and research, and postulated ones. A mediator is granted the right to control the course of proceedings by establishing a schedule for meetings and monitoring their course. Initially, a mediator may establish the course of the mediation procedure with parties, and determine jointly with them when and meetings take place, including separate meetings (caucus). This also includes arrangements regarding the recording of the mediation meetings, and how to inform workers of a course of negotiations by parties. Then, there are rights for mediators to have access to all relevant documents, to analyze the claims and positions of the parties, the genesis of the conflict, and the course of negotiations. In some cases, the mediator may request or ask an additional expert to develop opinions and test the mediation process.

The postulated rights consist in a possibility to attract parties’ attention to the need to make detailed and additional arrangements regarding the subject of a dispute or to make use of experts’ opinions, e.g. economists or lawyers. Mediation can go on from a few hours to a week, with no legal time limitations.

4.3 Ending the Mediation

Mediation proceedings are finished by concluding an agreement or signing a report of divergences. Both the signing of an agreement and the report of divergences in the event of failure to reach an agreement, are executed with the participation of a mediator. The legal regulations in force do not contain any guidelines regarding the content of an agreement. The agreement binds parties and constitutes a source of labor law, within the meaning of article 9 of the Labor Code. In the event of failure to reach an agreement through the mediation procedure, the Act imposes an obligation to draw up a report of divergences with the participation of a mediator. A report of divergences should contain clearly formulated positions of the employer and the trade unions and it should also include information related to the course of the mediation and a difference of positions that prevented parties from reaching an agreement.

If a mediator fails to involve the parties in actual negotiations, he may, and should, finish his mission. It is to be noted that the legislator does not determine a time period for the mediation proceedings. Their duration depends on the parties’ will and a mediator’s assessment. The mediation should be conducted as long as there’s still likelihood to reach an agreement, from the perspective of its participants. A report of divergences is drawn up if the mediation fails. A report of divergences may exclude some matters, and leave the remaining ones to be reconsidered at a negotiation level. It is possible to suspend a collective dispute (if it’s is not covered by the employment law), which enables unions to save face, and it is also convenient for the management board which must excuse themselves before the supervisory board. Another option is to stop the mediation, referring back to the negotiation phase when a mediator is in a way. Another technique that mediators can use is to disagree to sign a report of divergences—giving some time for parties to discuss how to avoid a strike.

5 Effectiveness of the System

The interviewees are not in accord whether there is any documentation of success. As mentioned earlier, only few collective conflicts are subject to mediation, and there is no clear record of the agreement level. The respondents confirm that it is hard to assess in an unambiguous way whether mediation ended in success or failure. When mediation is only a formal condition to declare a strike, it may mean a short-term success of workers. Nevertheless, the evaluation of the situation may change in the long run. Success should be measured by a final outcome including profits and losses seen from the perspective of both parties to the conflict. Courts and mediation centers were indicated as being in possession of such documentation. Nevertheless, all the respondents unanimously expressed that the satisfaction level of mediation and the level of trust are not documented, although in the case of the latter, it can be dealt with at an individual level (collecting opinions about particular mediators) and at a group level (reported lack of confidence of employers towards active trade union members). It appears that there is no actual form of evaluating the mediation and mediator/mediators.

Certainly, it is possible to indicate numerous cases of collective conflicts in which the mediator’s work turned out to be a key player for reaching beneficial solutions. We can also find a number of professional mediators and persons advocating for mediation and understanding the idea of dialogue—both among employees and employers. There are still specific drawbacks and shortcomings of the mediation system in collective conflicts, which has a considerable impact on its effectiveness. According to the research subjects, the mediation procedure should be introduced at an earlier stage, not after negotiations are over. In this context, it appears that mediation today is too formal, as specified by the Act. The biggest weakness is the fact that mediation is activated at a specific stage because the Act provides so. This causes that in the current situation strikes do not occur, but disputes between employees and an employer remain in suspension for years and may trigger consecutive conflicts in the future. In the view of our respondents, mediation should be introduced (also) at the initial stage of a dispute. Another weakness is the limited number of situations which are formally considered collective conflicts. In such situations, mediation—if it is introduced—plays a role of a promotor of the dialogue culture and is not subject to the statutory regulation. Moreover, conflicting parties and mediators focus their attention on making the mediation procedure more flexible so that it could be possible to work with a co-mediator depending on actual needs.

Some corrective measures have been taken. In September 2016, the Labor Law Codification Commission preparing changes to existing regulations regarding both individual disputes (regulated by the Labor Code), as well as collective conflicts (regulated by the Act of Resolution of Collective Deputes) was established at the ministry level. The Commission’s task is to recodify the norms of individual labor law and to codify collective labor law according to the requirements of a changing labor market.

6 Conclusions

From the total of 1700 registered collective conflicts (2014–2016) (Krajewska, 2018), negotiations and mediations were provided in only 11% of cases and then in only 23 cases the parties reached an agreement after negotiations. Thus, there is a strong need to improve particular elements of the system and the dialogue culture. Mediation costs money and as long as the parties have to pay the mediator’s labor costs, they won’t hire them. Currently, there are no legal regulations regarding the compulsory fund created by employers to cover mediation costs.

On the other hand, the court in legal proceedings encourages parties to reach an agreement, which is an incentive for parties to show their efforts to reach an agreement, and also encourages the use of mediation.

An important question would be how to get parties interested in mediation. It might be helpful to know how long it will take to finalize the case. What is needed is a wider knowledge about mediators’ professional competences. Even among specialists, there is no conviction about the legitimacy of using mediation. Some of them treat mediation rather as a hobby and not as a profession that could be a permanent job. Mediators operating outside the area of collective disputes are sometimes considered as those who are taking clients away from lawyer’s offices. This suggests there is a lack of mutual understanding of parties’ needs. Mediation implements one of the functions of employment law—the irenic function. However, if the obligation of mediation is imposed from above, to some extent the idea of mediation is contradicted. A good idea could be to introduce a direct regulation regarding mediation in the Labor Code (for example, extending a catalogue of methods indicating how to enforce claims by workers).

The applicable Act in Poland comes from 1991, from the onset of the transformation period of Polish economy and is no longer adequate to current conditions, which contributes to the ineffectiveness of the mediation system. In a number of industries, conflicts are handled with indirect decision-makers, e.g. the minister of health or education, and not with direct decision makers, as for example the company director. This poses an obstacle for reaching an agreement, regardless of using mediation or not.

Collective disputes are most often of financial nature, as seen in the conflict involving the Polish Teachers’ Association regarding middle schools, which has a wider context. Some disputes are of formal nature—for example the teachers in conflict with the government must first handle the conflict at local level, which is affected when, for example, the city mayor supports their activities and postulates towards the government. Our study shows that on the list of registered mediators, information about their profession and experiences is lacking, i.e. specializing in health care system (it is unnecessary to clarify the operating rules in this individual discipline).

The subjects are aware that there’s a value-creating aspect to mediation in such that no one loses or wins—both parties are equally ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. It is value added in the working environment, since these persons may still work together and it is beneficial for the working environment. Mediation emphasizes the educational aspect—there is no time for that in court proceedings. On the other hand, the legal fees in court mediation might exceed the costs of conventional ADR’s. It might be appropriate to increase the number of trainings for both parties in conflict, focusing on more modern approaches to social issues and employment law, since one of the sources of conflict is the lack of knowledge. As for mediations not regarding collective disputes, it is necessary to align the legal environment and the issue of pay for mediators. It would be also important to promote mediation not only for collective disputes, but also as a method for resolving other types of conflicts. There is a need for institutional improvement, a change in the law, such as defining what a mediator can or cannot not.

There is no monitoring of how the conflict between the parties develops. Strikes are a form of indirect information about failed mediation. Some issues have been elaborated through practical operation, but they are not standardized; there is no definition for mediators and their legal powers. The competence level of mediators is not equal and the lists of mediators are not updated (for example, some of them are inactive but still appear on the list). One respondent would like mediators to have a bigger impact on the outcome of the mediation, and to have some possible sanctions to be imposed by the Minister of Labor on employers who are not cooperative in mediation.

Employers are sometimes unprepared for mediation and in some cases appear as arrogant, as expressed in the interviews. A mediator should have the possibility to report about such cases. Problems and conflicts may be similar for different employers, but at the moment there’s no option to negotiate regulations that affect them all, which means that mediation must be conducted separately for each work establishment, even if there is the same management body/owner (e.g. Governor of Voivodeship/city mayor). Wouldn’t it be easier to negotiate such discrepancies with the government in order to resolve them at national level, for the benefit of the whole country?

An additional issue which might appear, is the gender bias, regularly perceived towards female employee representatives. These are not always respected, and take serious, despite their better preparation and knowledge than other parties at the table. It is also worth considering the functioning of alternative methods for settling disputes in workplaces where trade unions don’t operate. How could workers be represented in places where there are no trade unions? The respondents also pay attention to the fact that there are psychological barriers in the Polish society regarding mediation, for example a lack of openness in communication and a low level of trust. To be able to apply mediation with a broader perspective, a change in the society is also needed.

Notes

- 1.

The data illustrating collective conflicts in Poland come from statistical yearbooks of the Central Statistical Office (2016) and reports published by respective ministries responsible for labor and social policy (2014–2016), as well as interviews conducted with mediation parties (2016–2018).

- 2.

The unions report higher level of unionisation, but recent survey on a representative sample of adults indicate that only 5% respondents declare affiliation to trade union (Feliksiak, 2017).

- 3.

Journal of Laws of 2015, entry 295. The provisions of labor law in Poland are divided into collective and individual. Collective conflicts regulate the so-called collective labor law as opposed to individual conflicts regulated by the labor code.

- 4.

The respondents complained that the list is rarely updated. In 2018, there were 206 mediators in the list in February, but at the end of May only 80 remained.

References

Act on Resolution of Collective Disputes (Journal of Laws of 2015, entry 295). Retrieved from http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19910550236/U/D19910236Lj.pdf.

Feliksiak, M. (2017). Działalność związków zawodowych w Polsce. Komunikat z badań. NR87/2, s. 1–11. Retrieved from http://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2017/K_087_17.PDF.

Goś-Wójcicka, K., & Sekuła, T. (2015, July 13). Związki zawodowe w Polsce w 2014 r. (Trade unions in Poland in 2014). Retrieved from https://stat.gov.pl/download/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5490/10/1/1/notatka_zz_1007_ost.pdf.

Kawalec, G. (2009). Standardy pracy mediatora. Retrieved from http://www.dialog.gov.pl/dialog-krajowy/spory-zbiorowe/standardy-pracy-mediatora/.

Kożusznik, B., & Polak, J. (2015). Employee representatives in Poland. How are they perceived and what are the expectations by employers in Poland? In M. Euwema, L. Munduate, P. Elgoibar, E. Pender, & García, A. (Eds.), Promoting social dialogue in European organizations (pp. 123–134). New York: Springer.

Kożusznik, B., & Polak, J. (2016). Regulation of influence. An ethical perspective on how to stimulate cooperation and trust in innovative social dialogue. In M. Euwema, L. Munduate, & P. Elgoibar (Eds.), Building trust and constructive conflict management in industrial relations (pp. 169–184). New York: Springer.

Krajewska, S. (2018). Monitoring konfliktów społecznych. Retrieved from http://www.dialog.gov.pl/monitoring-konfliktow-spolecznych/.

Kurzynska, K. (2008). Spory zbiorowe i mediacja (Collective disputes and mediation). Retrieved from http://www.dialog.gov.pl/dialog-krajowy/spory-zbiorowe/spory-zbiorowe-i-mediacja/.

Lukawska, I. (2008). Biuletyny/książki/broszury. Retrieved from http://www.dialog.gov.pl/promocja-dialogu/publikacje-dialogu/biuletyny-ksiazki-broszury/.

Rozporządzenie Ministra Gospodarki i Pracy z dnia 8 grudnia 2004 r. w sprawie warunków wynagradzania mediatorów z listy ustalonej przez ministra właściwego do spraw pracy. Dz.U. 2004 nr 269 poz. 2673. Retrieved from http://prawo.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20042692673/O/D20042673.pdf.

Sieczkowski, M. Kielecki case kryzysowy (Kielce crisis case). Retrieved from http://www.proto.pl/PR/Pdf/art_sieczkowski.pdf.

Social dialogue. Retrieved from https://www.mpips.gov.pl/en/social-dialogue/.

Statistical Yearbook of Labor. (2015). Rocznik Statystyczny Pracy (2015). Warszawa: Główny Urząd Statystyczny.

Sukces biskupiej mediacji, strajk MPK zakończony. (2007, August 30) The success of episcopal mediation, the MPK strike ended. Retrieved from https://www.wprost.pl/kraj/112991/Sukces-biskupiej-mediacji-strajk-MPK-zakonczony.html.

Wach, K. (2007). 18 dni strajku w MPK (18 days of strike at MPK). Retrieved from http://infobus.pl/18-dni-strajku-w-mpk_more_67156.html.

Żołyński, J. (2013). Strajk i inne rodzaje akcji protestacyjnych jako metody rozwiązywania sporów zbiorowych. Warszawa: Lex a Wolters Kluwer business.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Aleksandra Cichos for her help in gathering data for Study 1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kożusznik, B., Chrupała-Pniak, M., Brol, M. (2019). Mediation and Conciliation in Collective Labor Conflicts in Poland. In: Euwema, M., Medina, F., García, A., Pender, E. (eds) Mediation in Collective Labor Conflicts. Industrial Relations & Conflict Management. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92531-8_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92531-8_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-92530-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-92531-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)