Abstract

Collective conflict in organizations are costly, for all stakeholders, including society. Therefore, regulation of collective labor conflict is an essential part of industrial relations. Conciliation and mediation are part of these regulations. This chapter explores the different features of collective conflict and introduces a new model to analyze third party interventions, including conciliation and mediation.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

A BBC news headline on April 12th 2018 reads: “Lufthansa and Air France flights grounded by strikes. Two of Europe’s biggest airlines have been hit by strike action, grounding hundreds of flights and affecting tens of thousands of passengers. Lufthansa has been forced to cancel 800 of its 1600 scheduled flights because of a walkout by public sector workers. At the same time, Air France has cancelled one in four of its flights as airline staff takes action in support of a 6% pay claim.”Footnote 1

KLM-Air France was confronted with actions by their own staff. The conflict continued and escalated further. The CEO tried to force a way out, by making a poll among the employees. On May 7th: “KLM-Air France shares plunged after its chief executive pledged to resign because he had failed to quell labor unrest, throwing the company’s strategy into question. The French president Macron is expected to appoint a mediator now.”Footnote 2

Lufthansa was here facing major losses due to actions of civil servants who went on strike, as part of their negotiations with the government. Lufthansa was not a party in this conflict. “It is completely unacceptable for the union to impose this conflict on uninvolved passengers” said Bettina Volkens (Lufthansa’s head of human resources). This however was different one week later.

April 18th, Munich: “Today pilots went on strike at Lufthansa, knocking out 3200 flights according to the company’s skeleton timetable. The four-day work stoppage will be the biggest stoppage labor disruption in the German airline’s history. More than 4000 of Lufthansa’s 4500 pilots are members of the Cockpit Association, which in May demanded pay hikes of 6.4%, a no-layoffs promise and commitments from the airline not to outsource operations to lower-pay subsidiaries. With a deadlock after months of talks, Cockpit Association members voted last week to authorize an all-out stoppage.Footnote 3”

Also in January 2018, media worldwide reported on the public transport in Sydney, which came to a stop. Actions by the drivers—due to changes, quality issues, increasing workload, and for the drivers an unacceptable wage offer—created a deadlock in the negotiations between workers and management. A new strike was blocked by the Fair Work commission. In response the national secretary of the Rail, Tram and Bus Union, Bob Nanva, said “this decision marks the death of the right to strike in Australia”.Footnote 4

This last case clearly points to the third party in the conflict. The Fair Work commission playing a mediating role, however also ruling against the right to strike in the Sydney case. In each case an important question is: which third party is there to help the conflicting parties to come to a negotiated agreement? And were there third parties available earlier in the negotiations that could have prevented this escalation? Mediators, conciliators, facilitators and arbitrators all might play a role in preventing and ending collective conflicts.

Collective conflicts between employers and employees regularly escalate at high costs, and therefore most countries worldwide offer different third party interventions and mediation services to solve these conflicts. Also, preventive forms of third party training, facilitation, and conciliation are growing in many countries. In Europe, the EC actively promotes such initiatives under the legal framework of social dialogue. Different studies show the need among social partners, employers, unions and other stakeholders, to innovate industrial relations and social dialogue (Cutcher-Gershenfeld, Kochan, & Calhoun Wells, 2001; Euwema, Munduate, Elgoibar, Garcia, & Pender, 2015; Munduate, Euwema, & Elgoibar, 2012; Weltz, 2008). One of the essential components in this innovation is supporting social partners, especially when negotiations are stuck, agreements cannot be reached, or rights are not respected, and conflict escalation might occur. Traditions differ among countries in this sense, having different approaches in providing such mediation assistance. However, there’s a lack of knowledge on how these conflict resolution systems work and how to further promote development. This book focuses on the analysis of mediation systems in collective labor conflict, offering ways to prevent and manage these conflicts, bringing some light over the current knowledge gap about: (a) the actual functioning of these services; (b) the conditions to promote the use of mediation; (c) good practices of effective mediation interventions.

1 Collective Labor Conflicts

Collective labor conflicts are an inevitable part of organizational life. Tensions between the interests and rights of employees, management and owners, being shareholders or public agents, can easily escalate into destructive levels. For that reason, societies develop legal frameworks to regulate these conflicts. An important element in these regulations is the role of third parties in managing the conflict. In the traditional approach, parties go to court and make a claim towards the other, and the labor court has the final ruling. In the Australian case, the specific labor court decided that the Sydney transport’s announced strike was illegal. This leads to important considerations regarding the ongoing negotiations and the high societal costs, among others. Indeed, collective conflicts are frequently costly for organizations as well as for employees, but not less importantly, they can be costly for clients, users and society in general. The example of Lufthansa shows the impact of collective conflicts, not only for travelers, but also for other companies. Patients, students, clients or customers are not served, and communities can be disrupted. In that sense, labor conflicts can further escalate into societal conflicts. Although violence against people is less usual in most industrialized societies, injured and even dead people are not uncommon in labor and social conflicts in countries with a conflictive history and great power distance between companies and employees, for example in many South-American and African countries, including South-Africa (Medina, 2016).

Collective conflict management is a highly regulated process around the world. Most countries have labor laws, that defend the association of workers in unions, and in works councils, representing the employees in the organization. Furthermore, in a majority of countries around the world employees have the right to strike to defend mutual interests. However, in many countries, for example in France, the right to strike is limited or even absent for specific jobs which have high societal impact (such as the police or the military). As strikes and other collective actions have high costs, in many countries these actions are only legal when organized by official recognized organizations, such as unions. Furthermore, in some contexts strikes are only legitimate after serious attempts to negotiate and solve the conflict. Such attempts include negotiations and meetings guided by facilitators or mediators. Usually, parties have the option to go to court, however the judicial system is collapsed in some western countries, is costly for parties and government, and their decision might not solve the underlying issues. For this reason, states facilitate the use of mediation for managing labor conflicts.

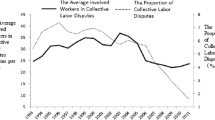

The court in Sydney declared the strike by the train drivers illegitimate. The response from the union’s side was that the ruling marked “the death of the right to strike in Australia”. A rather dramatic statement, demonstrating that rhetoric is a key element in escalated conflict. It however also signals a global trend, where the role of unions is shifting (Euwema et al., 2015), and the amount of strikes is decreasing. Brown (2014) reports a strong decline in union membership in most countries over the past 30 years as well as a reduction of strikes. This can be explained by three major trends: the reduced power position of unions; new and more cooperative models of industrial relations; and new models of third party assistance, also aiming at the prevention of strikes. This is clearly demonstrated for example in the UK (Dix, & Barber, 2015; Dix, & Oxenbridge, 2004). In Spain some mediation systems were introduced during 1990’s decade as a mandatory procedure for collective conflicts, preemptive to strike announcements or the initiation of a court demand. This substantially reduced costs related to strikes (Martinez-Pecino, Munduate, Medina, & Euwema, 2008; Warneck, 2007) (Fig. 1.1).Footnote 5

Average amount of days not worked between 2000–2016 in European countries. Source https://www.etui.org/Services/Strikes-Map-of-Europe (At the Etui website following this link more detailed information for each country and year is available.)

In most countries nowadays, also arbitration, conciliation and mediation are part of national conflict management systems, previous to the judicial court. According to Brown (2014), there is a global trend towards greater use of Alternative Dispute Resolution systems (ADR), where parties are assisted to come to an agreement, as alternative to the judicial system.

Brown (2014) argues that governments—inside and outside of the European Union—have promoted the creation of quasi-judicial processes, by the mean of institutions that offer conciliation or mediation which facilitate the resolution of these collective conflicts previous to strike. The most notable differences refer to the extent to which they can be considered judiciary as opposed to carried out by non-legal specialists. Despite the different economic and political backgrounds of each country, there are some important commonalities, especially during recent years (Valdés Dal-Ré, 2003). For example, countries which were at some point in time very judicial, such as Spain, are becoming less so. Likewise, systems which relied more on voluntary approaches such as Britain are increasing the regulation of collective disputes. A notable trend in European countries is the preference for voluntary approaches, as encouraged also by the European Commission in the year 2000. We can see a spread of voluntary conciliation, mediation and arbitration procedures for dispute resolution, due in part to the lower costs and fast resolutions that these practices often achieve, and the building, restoration and maintenance of relations between the parties on the long run.

Indeed, third parties in collective conflicts can have many different roles. And all over the globe, we find a large variety of such actors. There is a whole array of arbitrators, mediators and facilitators who might be acting as third parties. When the stakes are high, and the conflict is escalated, often public persons, politicians, religious leaders, or mayors, act as third parties. However, there are also often institutional third parties, professional mediators and facilitators.

Given the high stakes, it is worth to reflect on the design of conflict management systems in relation to these collective conflicts, and to explore how these third parties act and their effectiveness. This indeed is the aim of this book. Initiated by the EC, recognizing the importance of social dialogue and prevention of conflict escalation in labor relations, this book considers third party assistance in different stages of conflicts and aims to learn from good practices across countries and systems.

2 Collective Conflicts in Organizations

Conflict is a reality at many levels at work; between individuals, teams, departments and organizations. We define conflict between two or more parties (individuals or groups), if at least one of the parties is offended, or is hindered by the other (Elgoibar, Euwema, & Munduate, 2017). Collective labor conflicts traditionally are focusing on the relation between management and groups of employees (mainly unions). According to the ILO, the topic of these conflicts is often focused on the rights or interests of theses groups. This differs from individual labor disputes, which are those that arise within the relationship between an individual employee and his or her employer. Labor conflicts can take place at different levels within organizations, however also at sectorial level, or even national and international level. The ILO’s definition of labor conflict is essentially referring to only one type of relation within organizations: the relation between employer and employee. The organizational reality evidently presents many other forms of conflicts, such as interpersonal conflicts between colleagues, also at different hierarchical levels. For example, when a schoolteacher has a conflict with a school team leader over how to elaborate a syllabus, this is not a conflict with the employer. In the same school, the department of natural sciences might be in conflict with the department of arts over allocation of resources. Such conflicts between groups of employees also are conflicts where groups participate, but the conflict issues and conflict dynamics are not related to the employer-employee relation. However, when teachers negotiate about an increase of salary with the school owner, this is traditionally seen as a “collective labor conflict”, because the conflict parties are employer and employees, and the issue has an impact on a larger group of employees.

There is substantial literature focusing on handling interpersonal and intragroup conflicts in organizations (e.g. De Dreu & Gelfand, 2008; Rahim, 2017; Roche, Teague, & Colvin, 2014). This literature is mostly separate from the literature on intergroup conflicts that try to understand conflicts between groups and also separate from the ‘labor conflict’ literature, rooted in the employer-employee relationships. This literature is often more related to the legal analysis, formal regulations, social structures, collective bargaining and the influence and role of unions.

2.1 Collective Labor Conflicts Over Interests and Rights

In this volume we focus on collective labor conflict, that is focusing indeed on the relation between employees and employer. Many authors differentiate two types of collective labor conflicts: either over interests or over rights (Foley & Cronin, 2015; Martinez-Pecino et al., 2008). Disputes over interests are those in which parties attempt the modification or substitution of existing agreement terms, for instance, the negotiation of a collective agreement. Disputes over rights are those which deal with the interpretation and application of existent rules such as laws or collective agreements. There are differences in the effectiveness of negotiation in both types of conflict, with conflicts of interest easier to resolve than legal disputes (Medina, Vilches, & Otero, 2014). In the same way, third party interventions also differ in effectiveness and strategies in both types of conflict (Martinez-Pecino et al., 2008). Surprisingly, the scarce studies investigating collective conflicts, are limited to conflicts of interest. The social impact of these conflicts for society makes it necessary to gain a deep comprehension of them (Macneil & Bray, 2013). In this book, we certainly stretch beyond collective bargaining, as many conflicts in organizations occur related to different interpretation of rights. For example in the case of the Sydney train drivers, who are forced to work overtime, which in fact is an issue of rights.

2.2 Conflicting Parties

The conflicting parties and conflict issues in collective labor conflicts can be highly divers. This can be a first line supervisor in conflict with his or her team over the working hours; the director of a school in conflict with the sport teachers over the sports facilities at the school; management of a bank in conflict with the works council over payment of bonuses; or the top management of a mining company in conflict with unions over working conditions. Conflicting parties can also be at sectoral or national levels. For example primary school teachers went on strike in 2018 for better working conditions in the Netherlands.Footnote 6 Conflicts at sectoral and national levels bring usually other actors to the scene. Typically, from both sides, professional agents represent the interests of the primary parties, negotiating on behalf of employers, including governments, and employees. In this book we primarily focus on conflicts at organizational level. That is conflict between one employer and a group of employees. These conflicts can be at different levels within the organization, including site or departmental level.

2.3 Representing Employees: Unions and Works Councils

When we focus on representatives, in most countries world wide, and certainly within Europe, there are two basic institutional actors on the side of employees: inside the organization we find works councils and health and safety committees, and outside the organization we find unions representing the interests of workers. These bodies are usually involved in different types of conflict.

Unions, strikes and mediation

Within the EU, usually unions have the only right to call for a strike. Before going into social action there has to be in many countries an attempt to solve the conflict through conciliation or mediation. Such is for example the case in Spain, Portugal, and Belgium.

Works councils, deadlock in decision making and mediation

Works councils are the formal bodies of dialogue between management and elected employee representatives. Organizations in most EC member states have to inform, consult and even need the approval of the works council when it comes to decisions impacting the employees, such as restructuring. For example a Dutch health care organization facing financial losses proposed to restructure. The works council did not approve, which make progress impossible. Organized and free third party assistance to unfreeze these conflicts are offered for example in the Netherlands and Denmark.

3 Mediation and Other Third Party Interventions

The title of this book refers to ‘mediation’. Mediation is defined here as ‘any third party assistance to help parties preventing escalation of conflicts, helping to end their conflict, and find negotiated solutions to their conflict.’ The third parties in this definition can have different roles and positions, related to the society, culture, as well as level of escalation and specific parties involved. There is a wide array of terminologies used, which contribute to some confusion. In several countries we observe that what is officially called ‘mediation’, has mostly characteristics of arbitration, and often is a very formal process where representatives of the conflicting parties are negotiating for solutions, and the third party often acts in an evaluative way. This approach differs largely from the ILO promoted form of conciliation. Foley and Cronin (2015), updating the ILO instructions, refer to conciliation and consider this also as mediation, and promote clearly a non-evaluative approach, mentioning the conciliator should not offer opinions (2015; p 59).

-

$$ {\text{Mediating}}\,{\text{between}}\,{\text{CEO}}\,{\text{and}}\,{\text{works}}\,{\text{councils}} $$

In the fall of 2017, in Germany the conflict between the union IG Metall and ThyssenKrupp over the planned steel merger with Tata Steel is escalating. Oliver Burkhard is asked as mediator and arbitrator.Footnote 7

Trade unionist Oliver Burkhard has demonstrated his negotiating skills during the recent events, and for this reason, the HR director is just the man for the job.

With the assistance of deputy Supervisory Board member and IG Metall secretary Markus Grolms, it is planned that Oliver Burkhard will head a task force, ThyssenKrupp reported on Saturday during a meeting. This task force will then decide for or against the merger. Heinrich Hiesinger’s plan is for the two steel companies to join forces, becoming the second-largest steel group in Europe.

Thousands of steelworkers demonstrated last Friday against the merger of the two steel businesses. Whether the two steel groups will merge to form a giant still remains to be seen. “I feel cheated, betrayed, but still defiant,” said Director of the Works Council for the Steel Division, Günter Back.

The Supervisory Board now has the task of discussing this in depth and providing advice. Alongside Burkhard and Grolms, the task force represents the Management Boards of the two corporations, as well as the employee representatives from the various steel locations.

-

$$ {\text{Mediation}}\,{\text{between}}\,{\text{employees}}\,{\text{and}}\,{\text{the}}\,{\text{corporation}} $$

As mediator, Oliver Burkhard is right in the middle. Now he has to mediate between ThyssenKrupp CEO Hiesinger and the employee representatives. However, he is under particular pressure to prove his skills this time. The mood of the 27,000 steel employees is understandably at rock bottom over the merger plans. If the steel merger goes ahead, this would mean up to 4000 jobs being cut, and thus also 4000 people seeing the ground crumble beneath their feet.

Works councils and IG Metall are concerned that the 200-year-old traditional company could now be totally devastated. In early 2018, the Supervisory Board will again discuss further plans, but the whole transaction is expected to take until the end of 2018. If the employee representatives continue to vote “No” to the planned steel division, the Supervisory Board Chairman Ulrich Lehner will have to force the project through using a double voting right—absolutely taboo under normal circumstances!

“The Management Board has ignored all the warnings and bet everything on a single card. This does not mean we are going to endorse their decision,” criticises Günter Back, Director of the Works Council for ThyssenKrupp’s Steel Division.

According to Back, the Works Council is now obliged to help shape this decision. Back tells us that this should now take place in such a way that “the worst” is prevented. At the same time, he sees by no means just 2000 jobs eliminated in Germany, but far more—a catastrophe for many of those involved.

4 Regulations, Roles and Relations: 3-R Model of Mediation in Collective Conflicts

Inspired by Budd and Colvin’s (2008) ‘geometry of disputes resolution procedures’, Bollen, Euwema, and Munduate (2016) developed the 3-R model of workplace mediation. This model has been adapted to fit the analysis of mediation in collective conflicts. The 3-R model refers to three different dimensions that are important to consider when deciding for mediating and what form mediation takes: Regulations, Roles and Relations (Fig. 1.2). The three dimensions together create a three-dimensional pyramid that is built upon different layers, going from the broader context at the bottom, to specific third party tactics at the top.

At the bottom of the pyramid, we find more general characteristics of the context that determine the availability and use of mediation for a specific collective workplace conflict: (a) the wider context of conflict management and conflict in sector and society, (b) the organizational conflict culture and (c) the availability of different third parties. An important feature for example is the right to strike for employees, the position of unions, the role of works councils at organizational and local plant level, and the differences in legislation and practices between public and private sector.

The top of the pyramid represents first (d) the structuring of mediation, (e) mediation styles, (f) strategies and (g) tactics used, that result in a specific mediation outcome.

Structuring of mediation focuses on who acts as mediators; is there a regulated team of mediators, and are these different depending on the level of escalation of conflict? Do mediators always act in pairs, teams, or alone? Mediation styles refer to the different approaches in mediation—sometimes even ‘schools’ or ideologies—varying from evaluative and directive styles (Della Noce, 2009), to transformative and facilitative mediation (Folger & Bush, 1996). Traditionally, in industrial relations mediation showed similarities with arbitration or shifted towards this. Styles where mediators (almost) act as arbitrators, contrast with a non-directive and transformative mediation style (Bush, 2002).

The mediator strategy refers to a broad plan of action that may help to decide which actions are needed to achieve some objectives in particular conflict situations. As such, it refers to the mediator’s (or mediation team’s) general way of working in the mediation itself. An example could be the choice to rely solely on caucusing, work with a few representatives in the joint sessions, bringing in experts, etc. Evidently, the mediator strategy is highly influenced by the mediation style the mediator(s) adhere to. As Foley and Cronin (2015, p. 58) describe: “Ultimately, the personal style of the conciliator, and their relationship with the parties will influence the types of meetings that take place; but always the decision as regards meeting types should be based on what is most appropriate in seeking to assist the parties to move towards agreement or resolution.”

In the Netherlands, the Social Economic Council provides free mediation service for collective conflicts. The structure here is, that three different mediation committees are present for different sectors. The mediation style is officially in all cases facilitative. This is an important shift with the 20th century, when mediation was more evaluative, and took form of hearing parties and giving a non-binding advice. Nowadays, joint sessions are the standard where the mediator aims to facilitate a constructive dialogue.

Mediation tactics, refer to the most detailed level and thus the actual mediator behavior: the specific communication techniques and instruments used by the mediator in the pursuit of certain objectives. The tactics used are the behavioral specifics of the mediator strategy chosen by the mediator.

-

1.

Regulations

The dimension Regulations refers to different regulatory frameworks towards collective conflict at societal, sectoral and organizational level. On a societal and sectoral level, this includes labor laws, as well as negotiated agreements on conflict management between social partners. On an organizational level, this refers to specific human resources policies which define conflict management including regulations for mediation, and for example the conditions under which external or internal mediators can be used, also in collective conflicts (Constantino & Merchant, 1996; Pel, 2008). This also relates to legal rights of employers, unions, and works councils. For example to unilaterally ask for third party support.

-

2.

Roles

The dimension Roles refers to the role expectations of the conflicting parties as well as to the roles of all persons potentially involved as third parties in the conflict. Conflicting parties have perceptions and expectations of their own and each other’s roles in collective bargaining. In some cases, the intervention of third parties is not an element of the culture of how conflicts are managed: ‘We should be able to manage this ourselves’ is often the standard, and also part of the negotiation culture ‘Professionals are able to solve their own conflict’. Top management particularly might perceive bringing in third parties as loss of face, as they have not been able to manage the employment relations. These cultural norms could affect the acceptance of mediation as a valid resource when conflicts appear.

The second element of this role dimension, explores all possible others who might intervene as third party in the conflict. We see that people occupying different types of functions are involved in management of collective conflicts as well as in mediation: arbitrators, legal counselors, union specialists, judges, as well as coaches and specialized trainers (for the improvement of social dialogue) regularly might be involved in different stages of escalated conflict. Not to mention different types of leaders, from political (party politicians) to societal (mayors, or respected neutral persons), to religious leaders, regularly act as mediators. This might be particularly the case, when the collective labor conflict transforms into societal conflict.

-

3.

Relations

The last dimension refers to Relations and describes the characteristics of the relations between the conflicting parties, and their relationship with the mediator. What are the formal and informal power structures that influence parties’ interaction and as such the mediation? What are the specific needs of the parties in relation to the conflict and what are their expectations for assistance by a third party? All this determines if and what types of mediation are suitable, or that other types of interventions by third party, like conflict coaching, are more appropriate. In collective conflicts, parties are often represented by agents. This creates specific dynamics, also in terms of relationship qualities. Agents might be replaced, and have their own interests and agenda in negotiation and mediation.

It is important to analyze the structural qualities of the relation such as the formal power structure between parties and the legal rights they derive from this. To what extent are parties interdependent and how is the power balance? At the same time, it is important to take stock of the psycho-social qualities of the relationship given that most labor relations are more than just instrumental (García et al., 2016, 2017). How do parties perceive each other? To what extent do they wish to reconcile? What is their attitude: cooperative or competitive? To what extent do they perceive justice? Both structural and interpersonal characteristics will determine what type of mediator, strategy and tactics are used best to come to a mutually acceptable and satisfying solution.

The 3-R model of mediation helps to analyze mediation in its context. First, it helps to understand the extent to which mediation is used, for what conflicts and how the process of entering the mediation is organized and functioning. Secondly, the model offers a framework to understand the choice for certain mediation styles, strategies and tactics based on the interplay of regulations, roles and relations. Finally, the 3-R model offers a tool to understand and explain specific outcomes of mediation, given the characteristics of the Regulation’s, Roles and Relations and their interplay.

5 Conclusion

Collective labor conflicts are an inevitable part of labor relations. Such conflicts can take place at different levels; from the shop floor, within organizations, up to sectoral, and national levels. Internationally operating organizations might well face cross border conflict. Worldwide there is a decline of escalated conflicts, in terms of industrial actions such as strikes. Also worldwide, ADR is promoted, particularly forms of conciliation and mediation. Many countries, as well as the EC, promote constructive management of collective labor conflicts through legislation, social dialogue and mediation. Currently, academic empirical research is mostly lacking on the different arrangements for third parties, the perception and expectations of parties involved, and the effectiveness (Wall & Dunne, 2012).

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) works to protect labor rights, including the right to strike and the right to freely associate. The “Resolution concerning the Abolition of Anti-Trade Union Legislation in the States Members of the International Labour Organisation”, adopted in 1957, called for the adoption of “laws ensuring the effective and unrestricted exercise of trade union rights, including the right to strike, by the workers”. Similarly, the “Resolution concerning Trade Union Rights and Their Relation to Civil Liberties”, adopted in 1970, invited the Governing Body to instruct the Director-General to take action in a number of ways “with a view to considering further action to ensure full and universal respect for trade union rights in their broadest sense”, with particular attention to be paid, inter alia, to the “right to strike” (ILO, 1970, pp. 735–736).

- 6.

- 7.

References

Bollen, K., Euwema, M., & Munduate, L. (2016). Advancing workplace mediation through integration of theory and practice. The Netherland: Springer International Publishing.

Brown, W. (2014). Third party processes in employment disputes. In W. K. Roche, P. Teague, & A. J. S. Colvin (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Conflict Management in Organizations (pp. 135–149). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Budd, J. W., & Colvin, A. J. (2008). Improved metrics for workplace dispute resolution procedures: Efficiency, equity, and voice. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 47(3), 460–479.

Bush, R. A. B. (2002). Substituting mediation for arbitration: The growing market for evaluative mediation, and what it means for the ADR field. Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, 3, 111–117.

Costantino, C. A., & Merchant, C. S. (1996). Designing conflict management systems: A guide to creating productive and healthy organizations. London: Jossey-Bass.

Cutcher-Gershenfeld, J., Kochan, T., & Calhoun Wells, J. (2001). In whose interest? A first look at national survey data on interest-based bargaining in labor relations. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 40(1), 1–21.

De Dreu, C. K., & Gelfand, M. J. (Eds.). (2008). The psychology of conflict and conflict management in organizations. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Della Noce, D. J. (2009). Evaluative mediation: In search of practice competencies. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 27(2), 193–214.

Dix, G., & Barber, S. B. (2015). The changing face of work: insights from ACAS. Employee Relations, 37, 670–682.

Dix, G., & Oxenbridge, S. (2004). Coming to the table with ACAS: From conflict to co-operation. Employee Relations, 26(5), 510–530.

Elgoibar, P., Euwema, M., & Munduate, L. (2016). Building trust and constructive conflict management in organizations. The Netherlands: Springer International.

Elgoibar, P., Euwema, M., & Munduate, L. (2017). Conflict management. Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology (pp. 1–28). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Euwema, M., Munduate, L., Elgoibar, P., Garcia, A., & Pender, E. (2015). Promoting social dialogue in European organizations. Human Resources management and constructive conflict behaviour. The Netherlands: Springer.

Foley, K., & Cronin, M. (2015). Professional conciliation in collective labour disputes. Retrieved from: http://ilo.ch/wcmsp5/groups/public/europe/rogeneva/sro-budapest/documents/publication/wcms_486213.pdf.

Folger, J. P., & Bush, R. A. B. (1996). Transformative mediation and third-party intervention: Ten hallmarks of a transformative approach to practice. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 13, 263–278.

García, A., Munduate, L., Elgoibar, P., Wendt, H., & Euwema, M. (2017). Competent or competitive? How employee representatives gain influence in organizational decision-making. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research Journal, 10, 107–125.

García, A. B., Pender, E., & Elgoibar, P. (2016). The state of art: Trust and conflict management in organizational industrial relations. In Building trust and constructive conflict management in organizations (pp. 29–51). Cham: Springer.

Macneil, J., & Bray, M. (2013). Third party facilitators in interest-based negotiation: An Australian case study. Journal of Industrial Relations, 55, 699–722.

Martinez-Lucio, M. M. (Ed.). (2013). International human resource management: An employment relations perspective. London: Sage.

Martinez-Pecino, R., Munduate, L., Medina, F. J., & Euwema, M. (2008). Effectiveness of mediation strategies in collective bargaining. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 47, 480–495.

Medina, F. J., Vilches, V., & Otero, M. (2014). How negotiators are transformed into mediators. Labor conflict mediation in Andalusia. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 30(3), 95.

Medina, F. J. (2016). Conflicts that increase their intensity. In F. Palací (Ed.), Work Psychology [Psicología del Trabajo]. Madrid: Sanz y Torres.

Munduate, L., Euwema, M., & Elgoibar, P. (2012). Ten steps for empowering employee representatives in the new European industrial relations. Madrid: McGraw Hill.

Pel, M. (2008). Referral to mediation: a practical guide for an effective mediation proposal. Amsterdam: Sdu Uitgevers.

Rahim, M. A. (2017). Managing conflict in organizations. Oxford: Routledge.

Roche, W. K., Teague, P., & Colvin, A. J. (Eds.). (2014). The Oxford handbook of conflict management in organizations. Oxford University Press.

Valdés Dal-Ré, F. (2003). Synthesis report on labour conciliation, mediation and arbitration in the European Union countries. In Labour conciliation, mediation and arbitration in European Union countries. Madrid: Ministerio de Trabajo y Asuntos Sociales.

Wall, J., & Dunne, T. (2012). Mediation research: A current review. Negotiation Journal, 28, 217–244.

Warneck, W. (2007). Strike rules in the EU27 and beyond: A comparative overview. Brussels: European Trade Union Institute.

Weltz, C. (2008). The European social dialogue under Articles 138 and 139 of the EC treaty. Amsterdam: Kluwer Law International.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

García, A.B., Pender, E.R., Medina, F.J., Euwema, M.C. (2019). Mediation and Conciliation in Collective Labor Conflicts. In: Euwema, M., Medina, F., García, A., Pender, E. (eds) Mediation in Collective Labor Conflicts. Industrial Relations & Conflict Management. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92531-8_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92531-8_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-92530-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-92531-8

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)