Abstract

Ageing is commonly considered as a serious social problem. Older adults are often regarded as the consumers of social welfare rather than creators and they are thought to be “incapable” and “worthless”. This article advocated a strength-oriented or empowerment-oriented perspective. Based on different empowerment models, this paper proposed an influence and process model of empowerment. It provided a framework to map the strengths of “incapable” people (as traditionally believed) and barriers to empowering them, and a practical reference to take action for empowerment during which participation was emphasized. Cases of empowerment for older people was introduced and analyzed following the framework of the model by which we provided a reference of empowerment-oriented practice for researchers and practitioners.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The ageing of populations is rapidly accelerating worldwide. For the first time in history, most people can expect to live into their 60s and beyond [1]. On the one hand, this shows the dramatic development of human society. On the other hand, it also brings new challenges. From a stereotype viewpoint, ageing is often considered as a serious social problem. Older adults are regarded as the consumers of social welfare rather than creators and they are thought to be “incapable” or “worthless” [2, 3]. The public always neglects older adults’ diverse capabilities and their positive impacts on the society. Consequently, the government and families tend to hold a negative view when dealing with the age-related issues, which seriously hampers the functioning and self-actualization of older adults and makes them a burden to both the government and their families [4, 5].

However, a report by WHO provides evidence that age and physical decline are not linearly related, as traditionally believed [6]. Older people in fact are diverse in their capabilities. Some older people are equivalent to middle-age people in physical functioning [7]. With the right policies and services in place, population ageing can be viewed as a rich new opportunity for both individuals and societies. Therefore, there is a necessity to change the paradigm from problem-based to strength-based stance which encourages practice with a focus on individuals’ potential and capacities rather than their limits [8, 9]. The strengths and empowerment perspective places emphasis on individuals’ inner and environmental strengths and resources of people and their environment rather than their problems and pathologies. From this perspective, the focus to work with older people is to help them maintain agency and create a supportive environment for them [10].

Empowerment theories have been applied to many disciplines such as management, social work, nursing and education. Many models are developed for empowerment research and practice. In recent years, researchers and practitioners in design discipline show a growing interest in this field. In the social background of ageing, the question of how design can help to empower older people calls for answers from both theoretical and practical perspective. Manzini proposed the concept of “enabling ecosystem” and suggested that design activities should focus on facilitating users and stakeholders and help people to solve their problems by their own rather than provide design solution for them directly [11]. However, how to facilitate, enable or empower people from a design perspective is unclear and the theory of design empowerment is lacking.

In this paper, we compared and analyzed different empowerment models and developed one for the design discipline. In order to demonstrate how this model can be applied in design, several cases of design empowerment for older people were analyzed using this model.

2 Empowerment Models

2.1 1-A Linear Empowerment Process Model

Conger and Kanungo developed an empowerment model in 1988 that focused on the process and action to empowering subordinates in the organization management context [12]. In order to differentiate it with the later empowerment process model by Cattaneo and Chapman [13], we refer to The Linear Empowerment Process Model based on its linear process.

This model divides empowerment in five stages that include the psychological state of empowering experience, its antecedent conditions, and its behavioral consequences. The five stages are shown in Fig. 1. The first stage is the diagnosis of conditions within the organization that are responsible for feelings of powerlessness among subordinates. This leads to the use of empowerment strategies by managers in Stage 2. The employment of these strategies is aimed not only at removing the external conditions responsible for powerlessness, but also (and more important) at providing subordinates with self-efficacy information in Stage 3. As a result of receiving such information, subordinates feel empowered in Stage 4, and the behavioral effects of empowerment are noticed in Stage 5.

This process can by roughly divided into 3 stages—diagnosis, intervention and results. In intervention stage, we can see both measures targeted on internal and external factors are taken. This process gives a detailed and practical guideline for organizational management based on identification of factors effecting empowerment.

2.2 The Contextual-Behavioral Empowerment Model

Fawcett and his colleague developed the contextual-behavioral model of empowerment in 1994 [14]. It includes three dimensions: the person or group, the environment, and the level of empowerment. It is assumed that the level of empowerment results from the interaction between personal (group) factors and environmental factors. The personal dimension represents the degree of personal or group’s strength-from vulnerable to strong. People with physical disability or less knowledge and experience may be less empowered and vice versa. The environment factors including opportunity, discrimination, information access may facilitate or restrict the empowerment outcome and status. The surface of the model depicts the level of empowerment that will be effected by the dynamic interplay of personal and environmental factors (Fig. 2).

With this model, Fawcett and his colleague identified 4 main strategies encompassing 33 specific enabling activities, or concrete tactics for promoting community empowerment. Those strategies include enhancing experience and competence, enhancing group structure and capability, removing social and environmental barriers and enhancing environmental support and resources [15].

2.3 The Social Work Model for Empowerment-Oriented Practice

The social work model for empowerment-oriented practice with older people was developed in 1994 by Coxs and Parsons and introduced to Japan in 1997 [16, 17]. This model provides a framework containing both a theory base and a practice framework. The empowerment practice includes a 4-dimensional conceptualization of problems and focus of interventions from micro to macro aspects (Table 1).

The practical part of this model empathizes on understanding of the personal, interpersonal, and political aspects of at-risk population’s situation and developing interpersonal support network. It stresses recognizing and working with the strengths and resource of clients including respect for diversity, which transfers the traditional problem-based paradigm to a strength-oriented paradigm. What is more, it encourages participation and a partnership in action [18].

2.4 The Iterative Empowerment Process Model

The iterative empowerment process model was built on the understanding that an increase in power is an increase in one’s influence in social relations at any level of human interaction, from dyadic interactions to the interaction between a person and a system. Six components are identified, namely meaningful and powerful goal, self-efficacy, knowledge, competence, action and impact. The model defines empowerment as an iterative process in which a person who lacks power sets a personally meaningful goal oriented toward increasing power, takes action toward that goal, and observes and reflects on the impact of this action, drawing on his or her evolving self-efficacy, knowledge, and competence related to the goal. In this model, the author underlines the importance of social context. Social context influences all six components and the links among them.

As shown in Fig. 3, the process is not linear, and a person may cycle through components repeatedly with respect to particular goals and associated objectives. The successful outcome of the process of empowerment is a personally meaningful increase in power that a person obtains through his or her own efforts [13].

2.5 Comparison of These Models

The four models above provide rich information for empowerment. Comparing these models, we can see the different focus in the following three aspects.

Factors or Process.

Some models lay emphasis on describing the influence factors of empowerment, while others pay more attention to provide a practical guideline step by step. For example, the contextual-behavioral empowerment model identified and clarified personal and environmental factors that affect the behaviors and outcomes associated with empowerment. Although it proposes many strategies for empowerment at the same time, most of them were based on certain factors that do not show a practical sequence. How to apply them in practice is unclear. In comparison to the factors model, Conger and Kanungo’s linear empowerment process model and Cattaneo and Chapman’s iterative empowerment process model provide the practical guideline step by step. By a clear process, the practitioners can take empowerment-oriented actions. However, without a comprehensive recognition of influence factors of empowerment, the action may not work.

Different Dimensions of Factor Categories.

Different models divide influence factors in different way. The social work model for empowerment-oriented practice clarified the influence factors into 4 dimensions, which can be divided into 3 categories– personal, interpersonal, and political aspects. While in the contextual-behavioral empowerment model, the factors are divided into two categories, personal/group factors and environmental factors, even though the environmental categories can also include the political environmental factors. This model also discriminates the positive aspects (supports) and negative (stressors and barriers) aspects in its environmental factors, which shows a specific direction for action. For example, to deal with negative factors, the practitioners may try to restrict or remove them and verse vice.

Besides the 4 models which distinguish different categories by different criteria, Rich et al. examined different types of empowerment [19] and grouped them into 4 categories, namely “formal empowerment” (or societal empowerment, in which the larger political decision-making system allows some measure of meaningful local control), “intrapersonal empowerment”, “instrumental empowerment” (via individual citizen participation) and “substantive empowerment” (via group action).

Different terms were utilized in order to distinguish different influence factors or dimensions of empowerment. Some terms described the categories from different perspectives and some terms include other terms in their scope, which makes the clarification ambiguous. We divide these terms into two aspects. One refers to the domain of empowerment, such as personal, intrapersonal, and environmental aspects. The other refers to the properties of empowerment that make a distinction between the positive and negative factors.

Linear or Iterative.

In two empowerment process models, one presents the process in a linear form while the other is iterative. By the iterative empowerment process model, Cattaneo and Chapman argued that the components of the model influence each other in dynamic ways. In other words, the action of empowerment and reflection on impact after action will affect the initiative goals, thus start a new round of empowerment action. They cited Kieffer’s idea to convince readers.

“The longer participants extend their involvement, the more they come to understand. The more they understand, the more motivated they are to continue to act. The more they continue to act, the more proactive they are able to be. The more proactive they are able to be, the more they further their skill and effect. The more they sense their skill and effect, the more likely they are to continue [20]”.

Therefore Cattaneo and Chapman suggested take empowerment-oriented action in an iterative way. Since power is a rational construct, it is a relative concept rather than an absolute concept. We believe empowerment as a process has not a definite end.

3 An Influence Factors and Process Model of Empowerment

3.1 Introduction of the Model

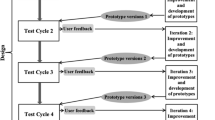

Based on the review of the prior four models, a process model of empowerment based on the influence factors was developed. As shown in Fig. 4, this model described empowerment from both spatial and temporal dimensions.

From a spatial dimension, this model identifies the influence factors of empowerment, including both the intrapersonal and interactional aspects. Intrapersonal aspects refer to the factors influenced by individuals’ internal condition such as knowledge and experience which may subsequently influence personal confidence and competence. Interactional aspects refer to the external factors including “person to person interaction” (interpersonal) and person to environment interaction (environmental, societal and political).

Additionally, distinguished from a problem-based paradigm to solve age-related issue, this model addresses the positive factors of older adults based on a strength-oriented paradigm and utilized “strengths” and “barriers” to replace “problems”. These two pairs of criterion–intrapersonal/interactional and strength/barriers divide the factors’ space into 4 subspaces, namely intrapersonal strengths, intrapersonal barriers, interactional strengths and interactional barriers.

From a temporal dimension, this model presents an iterative empowerment process. In order to empathies the agency of vulnerable people, this process encourages practitioners to start from working on intrapersonal factors. From a strength-oriented principle, people’s strength should be paid more attention in action. Therefore, an expected process of empowerment may start from enhancing intrapersonal strength and removing intrapersonal barriers to enhancing interactional strength and removing interactional barriers based on comprehensive identification of those factors. It should be noted that not all the steps must be addressed in practice, sometimes it only need to focus on one or two steps of them.

Participation is the key component of this model. Rappaport endorsed the Cornell Empowerment Group’s definition of empowerment as involving respectful, caring and reflective participation in a community group in order to gain equal access to and control of resource [21]. Zimmerman considered participation in community organizations is one way to exercise a sense of competence and control. Participation in a variety of community organizations has reported an increase in activism and involvement, greater competence and control, and a decrease in alienation [22]. Maton and Salsem’s paper also viewed empowerment in general terms as a process enabling individuals, through participation with others, to achieve their primary personal goal [23]. Based on the prior viewpoints on empowerment, participation is crucial for people to be empowered.

In the iterative empowerment process model, Cattaneo and Chapman adopted the term action as a component. They argue that participation is improper because it is only one of an almost limitless range of action. However, we think participation is precisely a specific way of taking action for empowerment. Empowerment as a relational construct describes a status that one controls resource and has power over others. It requires interaction with other people, organizations and resources. Someone may take actions by themselves without any interplay with others and this process can improve self-efficacy. Without participation, self-efficacy cannot transfer to social impact. However, empowerment addresses on social practice to promote social change [24].

3.2 Designing Participation as Empowerment

The above model illustrates the influence factors of empowerment and a generic process to empower people. How design can play an important role in this process? We consider participation as an essential aspect for empowerment-oriented design.

Reviewing empowerment in the design discipline, we find that empowerment related to participatory design frequently.

In the context of participatory design, users are encouraged to participate and exercise power in the design process. Correia and Yusop considered users’ democratic participation and empowerment as the core aspects of the Participatory Design [25]. Ertner et al. had conducted a review on 39 papers from the PDC (Participatory Design Conference) proceedings of 2008 and found 21 papers in which an enunciation of empowerment was evident [26]. In order to empower users via design participation, many approaches and tools were utilized and suggested. Visualization was suggested as a mediator for user participation and empowerment in neighborhood design [27]. Narratives have the ability to create imaginary worlds for the public and increase their active participation in social life via enabling social dialogue [28, 29]. Olivia’s research identified crafting activities as a way to allow older adults to participate in the design process [30].

Design outcomes can also be a mediator to encourage participation in empowerment-oriented design. Users can experience power by open-ended solution. Storni’s research shared a project on self-care technology for diabetes in which a mobile journaling tool was developed to enable the personalization of self-monitoring practices [31]. With this product, people with diabetes can participate in tracking the effects of their actions, thus improving a sense of control. In this case, users’ participation is an essential part of the solution. Therefore, the key of designing empowerment is designing participation. An open-ended and flexible solution may welcome participation with lower threshold and less restriction.

4 Cases of Design Empowerment for Older Adults

In this section, we illustrate four cases of design empowerment for older people.

A-Gingko house is a western restaurant with the value proposition of supporting senior employment enjoying life. In this restaurant, 90% of the employers are older people. Those people with rich life experience can amuse people when providing catering services for guests. Before joining the work, older people are required to attend repetitive training in order to overcome the problem of senior’s bad memory. The working duration is adjusted to 4–5 h one day with the consideration of their physical ability. All the vegetable in Gingko House comes from an organic farm where most of the employers are also older people who has many years of farming experience. Staffs transporting vegetables from the farm to the restaurant are also retired drivers [32].

B-“The Innocent Big Knit” is a public welfare program for helping people to overcome their loneliness in later life. This program asked older people and younger people to knit little woolly hats. They then put those hats on the drinks of smoothies. For every behatted smoothie sold, Age UK will receive 25p to help fund vital national and local services that combat loneliness for older people, in particular keeping people warm and well in winter. The idea snowballed and so far the people of the UK have knitted an astonishing 6 million hats. Together they’ve raised over £2 million for Age UK [33].

C-“Hosting a Student” is a co-housing program between independent elderly people and university students from outside Milan. Its initiative is based on a very simple idea: find lodging for students in the homes of elderly people who have a spare room. The young people do not pay rent as such, but contribute to the expenses of house-sharing by paying a monthly sum of about € 250–280, as well as performing practical tasks and providing company for the elderly person who, in addition to suffering less from loneliness, can enjoy the satisfaction of still feeling useful. Since 2004 over 650 house-sharing agreements have been established of which only eight were discontinued due to incompatibility [11, 34].

D-AARP Foundation Experience Corps is an intergenerational volunteer-based tutoring program to provide both older adults and children with opportunities to enrich their lives through literacy. This program inspires and empowers adults aged 50 and above to help students who have difficulties in reading in primary schools. Volunteers provide an average of 6–15 h of support each week throughout the school year. After one year, many students who work with Experience Corps volunteer tutors achieve as much as 60% improvement in critical literacy skills compared to their peers [35].

4.1 Mapping the Influence Factors to the Model

The above 4 cases identified different strengths and barriers of older people. Many activities in these cases are based on these strengths and barriers. We mapped them in the framework of the above model (see Fig. 5).

How to enhance or utilize the intrapersonal strengths and remove or avoid the intrapersonal barriers are evident in the case of “Gingko House”. For example, people who are employed by this restaurant are equipped with many skills such as farming and driving. Farming can be identified as a special strength of older people since farming is gradually lost in the rapid process of urbanization and the youth have few chances to learn it. These skills are identified and facilitated to produce value while matching to suitable work. Additionally, it is reported that guests speak highly of the senior waiters because of their rich experience since they might understand guests’ unique need better. What is more, some intrapersonal barriers of older people are also identified. With consideration of their memory loss and physical power limitation, the restaurant provided repetitive training and adapted staff time rota to a shorter duration.

In the case of “Hosting a Student”, most efforts are made based on identification of interactional factors of senior people. In Italy and many other countries, some older people often have a house with spare rooms. Meanwhile, they live alone in town and need help in everyday activities. The “Hosting a Student” program utilized their resource and bridge them with the needs of students who can not afford a relatively higher house rent but have spare time to company the elderly. However, the difficulty to enhance mutual trust between the older people and students is evident. In this case, The association Meglio Milano carried out a careful cross-analysis – of their psychological profiles – in order to match people who will be able to live their everyday lives together in the best possible way, and afterwards also provides support to avoid and solve tensions and misunderstandings [36].

4.2 Designing Participation

All of the four cases place great emphasis on designing participation. For example, “The Innocent Big Knit” provided many approaches calling for participation both online and offline. In order to lower the barrier of participation, many patterns of woolly hats were post on the website for beginners to easily find a pattern which is proper for their level. Video tutorials are also shown in website. In order to attract more expert participants, the organizers launched annually competition which allows participants to vote for their favorite hats. The winner hats will be promoted in Facebook. Offline activities included knitting together in senior house and at home. The website reported a story that an old mother teach her two daughters knitting hats at home. This report shows a Parent-Child Interaction scenario which attract much attention of participants.

“AARP Foundation Experience Corps” also provided diverse activities for participation. The organizers arranged a 30-hour training course for the senior volunteers during which they can build new social network and form mutual support group in 7–10 members. Each group will enter a primary school to help the young students in reading. Volunteers were encouraged to participate in regular meetings which allow them to make planning, discussion and socialize together. Those social participation activities proved to be beneficial for enhancing their physical and cognitive capabilities.

5 Conclusion

The shift from a problem-based paradigm to an empowerment-oriented paradigm shows a positive transformation to view population ageing. In the background of ageing society, the benefits of empowerment-oriented paradigm is widely accepted by many researchers and practitioners in many fields such as phycology, social work, and organization management. Many practices around the world also show the advantages for both senior individuals and the society. However, when this concept was introduced to the design discipline, it is important to think about how design can play a unique role for empowerment.

This paper proposed a design empowerment model which provides a framework to identify and map the influence factors of empowerment. This framework also gives a step-by-step guideline for practitioners to take action. More importantly, we argue participation as a key component in the process of empowerment since it bridges the action on the internal (intrapersonal) aspect with the external (interactional) aspect. We also argue that the key of designing empowerment is designing participation. The four cases provide a reference for empowerment for older people in practice. By these cases, we identified specific strengths and barriers and show the strategies to design for participation such as lowering the barriers to participation, attracting diverse participants in different capability levels and building networks between participants.

However, we have not provided a comprehensive list of strengths and barriers in the model. A survey will be conducted among older adults in the future to identify more strengths and barriers.

References

Dey, A.B.: World report on ageing and health. Indian J. Med. Res. 145(1), 150–151 (2017)

Guo, A.: Old-age social security research from a multi-discipline perspective. Sun yat-sen University Press, Guangzhou (2011)

Prince, M.J.: Apocalyptic, opportunistic, and realistic discourse: retirement income and social policy or Chicken Littles, Nest-Eggies, and Humpty Dumpties. In: Ellen, M.G., Gloria, M.G. (eds.) The Overselling of Population: Apocalyptic Demography, Intergenerational Challenges, and Social Policy. Oxford University Press, Toronto (2000)

Gao, S.: Financial burden of population aging and countermeasures. Local Finance Res. 1, 75–77 (2011)

Wu, P.: The dilemma and solution of one-child family in China Rural in the trend of the aging of population. Soc. Work 9, 87–89 (2012)

WHO: World report on ageing and health (2016)

Peeters, G., Dobson, A.J., Deeg, D.J., et al.: A life-course perspective on physical functioning in women. Bull. World Health Organ. 91(9), 661–670 (2013)

Cox, E.O.: Empowerment-oriented practice applied to long-term care. J. Soc. Work Long-Term Care 1(2), 27–46 (2001)

Moyle, W., Parker, D., Bramble, M.: Care of Older Adults: A Strengths-Based Approach. Cambridge University Press, UK (2016)

Chapin, R., Cox, E.O.: Changing the paradigm: strengths-based and empowerment-oriented social work with frail elders. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 36(3), 165–179 (2001)

Manzini, E.: Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation. The MIT Press, US (2015)

Conger, J.A., Kanungo, R.N.: The empowerment process: integrating theory and practice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 13(3), 471–482 (1988)

Cattaneo, L.B., Chapman, A.R.: The process of empowerment: a model for use in research and practice. Am. Psychol. 65(7), 646–659 (2010)

Fawcett, S.B., White, G.W., Balcazar, F.E., et al.: A contextual-behavioral model of empowerment: case studies involving people with physical disabilities. Am. J. Community Psychol. 22(4), 471–496 (1994)

Perkins, D.D., Zimmerman, M.A.: Empowerment theory, research, and application. Am. J. Community Psychol. 23(5), 569–579 (1995)

Cox, E.O., Parsons, R.J.: Empowerment Oriented Social Work Practice with the Elderly. Books/Cole Pub. Co., Pacific Grove (1994)

Inaba, M.: Aging and elder care in Japan: a call for empowerment-oriented community development. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 59(7–8), 587–603 (2016)

Gutierrez, L.M.E., Parsons, R.J.E., Cox, E.O.E.: Empowerment in Social Work Practice. A Sourcebook. Empowerment in social work practice. Brooks/Cole Pub. Co., Pacific Grove (1998)

Rich, R.C., Edelstein, M., Hallman, W.K., et al.: Citizen participation and empowerment: the case of local environmental hazards. Am. J. Community Psychol. 23(5), 657–676 (1995)

Kieffer, C.H.: Citizen empowerment: a developmental perspective. Prev. Hum. Serv. 3(2), 9–36 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1300/J293v03n02_03

Rappaport, J.: Empowerment meets narrative: listening to stories and creating settings. Am. J. Community Psychol. 23(5), 795–807 (1995)

Zimmerman, M.A.: Empowerment theory. In: Rappaport, J., Seidman, E. (eds.) Handbook of Community Psychology, pp. 43–63. Springer, Boston (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4193-6_2

Maton, K.I., Salem, D.A.: Organizational characteristics of empowering community settings: a multiple case study approach. Am. J. Community Psychol. 23(5), 631–656 (1995)

Freire, P., Moch, M.: A critical understanding of social work. J. Prog. Hum. Serv. 20(1), 92–97 (2009)

Correia, A.P., Yusop, F.D.: “I don’t want to be empowered”: the challenge of involving real-world clients in instructional design experiences. In: Tenth Anniversary Conference on Participatory Design, pp. 214–216. Indiana University (2008)

Ertner, M., Kragelund, A. M., Malmborg, L.: Five enunciations of empowerment in participatory design. In: Conference on Participatory Design, PDC 2010, pp. 191–194. DBLP, Sydney (2010)

Senbel, M., Church, S.P.: Design empowerment the limits of accessible visualization media in neighborhood densification. J. Plann. Educ. Res. 31(4), 423–437 (2011)

Anzoise, V., Piredda, F., Venditti, S.: Design Narratives and Social Narratives for Community Empowerment. In: STS Italia Conference. A Matter of Design: Making Society Through Science and Technology, Italy, pp. 935–950 (2014)

Prost, S., Mattheiss, E., Tscheligi, M.: From awareness to empowerment: using design fiction to explore paths towards a sustainable energy future. In: ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, pp. 1649–1658. ACM, New York (2015)

Olivia, K.R.: Exploring the empowerment of older adult creative groups using maker technology. In: CHI Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2017, pp. 166–171. ACM, New York (2017)

Storni, C.: Design challenges for ubiquitous and personal computing in chronic disease care and patient empowerment: a case study rethinking diabetes self-monitoring. Pers. Ubiquit. Comput. 18(5), 1277–1290 (2014)

Gingko House Homepage. http://www.restaurant.org.hk. Accessed 9 Jan 2018

The big knit Homepage. http://www.thebigknit.co.uk/about. Accessed 9 Jan 2018

MeglioMilano project page. http://www.meglio.milano.it/en/progetti/prendi-in-casa/. Accessed 9 Jan 2018

AARP Homepage. https://www.aarp.org/experience-corps/. Accessed 9 Jan 2018

Cipolla, C.: Relational services and conviviality. In: Satu Miettinen (Org.). Designing Services with Innovative Methods. 1 edn., pp. 232–243. TAIK Publications/University of Art and Design Helsinki, Helsinki (2009)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this paper

Cite this paper

Dong, Y., Dong, H. (2018). Design Empowerment for Older Adults. In: Zhou, J., Salvendy, G. (eds) Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Acceptance, Communication and Participation. ITAP 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10926. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92034-4_35

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92034-4_35

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-92033-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-92034-4

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)