Abstract

In this chapter we examine individual-level shifts in attitudes toward immigrants, government spending and the environment over sixteen years in Switzerland. We approach this inquiry with an eye toward the role of political parties in shaping people’s views on politically salient topics. We identify a great deal of year-to-year change in people’s views on these three issues, though they have stabilized significantly in recent years. We also find that individuals’ partisan leanings shape their stances on key issues over time and that this effect is strongest for young people’s views on immigration. This chapter contributes to our understanding of change and stability in Swiss politics and also adds to what we know about attitude development among democratic citizens.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

What explains changes in political attitudes? We consider the ways in which partisan choices relate to attitude change. While most studies of the partisan-attitude nexus use attitudes to explain party choices, we flip the script and consider the ways that partisan choices shape attitudes over time. The Swiss Household Panel Survey (SHP) provides an opportunity to evaluate shifts in individuals’ views on immigration, government spending and the environment over 16 years. This survey makes it possible to establish how stable these views and party choices are from year to year. It also allows us to model attitudinal changes to identify their chief predictors. These are essential inquiries if we are to understand the ways in which Switzerland has changed and remained the same since the turn of the century.

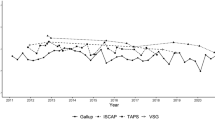

After decades of stability in Swiss electoral politics, recent elections have become less predictable. Notably, National Council elections are increasingly competitive. Notably, the Swiss People’s Party (SVP) has attracted hundreds of thousands of new supporters. Fig. 13.1 displays various parties’ electoral fortunes over the last two decades. The full, black line marks the ascent of the SVP across elections. The Greens have also grown in popularity, though more modestly. The remaining main parties, the Social Democrats, Christian Democrats and the Radical Democrats, weakened across these six elections (Swiss Federal Statistical Office 2016).

Swiss parties’ shares of National Council election votes

Source: Swiss Federal Statistical Office 2016

*As of 2011 election, Radicals’ (Free Democrats) share of votes includes Liberals: they merged in 2009 into FDP.The Liberals

These aggregate electoral patterns demonstrate that Swiss politics have changed significantly in recent years. Yet they do not offer much insight into shifts in people’s political views at the individual level. Our objective is to gain a better understanding of how (un)stable key political attitudes are for the Swiss. We also unpack the relationship between partisan choices and views on salient political issues over time.

Theoretical Framework

The partisan shifts depicted in Fig. 13.1 may indicate that people’s attitudes are changing and that parties’ electoral fortunes are shaped by these changes. For instance, it is possible that as anti-immigration attitudes rise in popularity, the SVP gains new voters over time as a result. But another interpretation is that increasingly competitive campaigns have attitudinal implications. In other words, it may be that parties shape the opinions of their supporters. Per this narrative, the SVP’s messaging influences its supporters’ views on immigration. Given the disjuncture between the post-war stability and more recent changes in Swiss politics, it is important to unpack these dynamics over time. It is imperative for our understanding of Swiss democracy to ask whether parties actively shape or passively reflect public opinion.

Political scientists debate the nature of the relationship between parties and attitudes. Classical theories of democracy and political behavior depict a citizen who decides which party to vote for based on his or her attitudinal preferences (Downs 1957; Campbell et al. 1960). This instrumental model of electoral choice puts policy preferences in the driving position; a citizen arrives at a party selection based on a sense of which party will deliver his or her optimal policies. Yet a contrasting view paints an image of electoral politics in which parties, themselves, shape public opinion. According to this psychological account, voters will shift their views in response to partisan cues. In order to remain consistent with a chosen party’s platform, voters will update their attitudes over time (Lodge and Taber 2000, Miller 2000, Sniderman and Levendusky 2007). These two narratives depict very different images of political behavior in democratic settings. We leverage the Swiss case to contribute to this big-picture debate. Given the high level of dynamism evident in Swiss politics over the past decade and a half, it presents an unusually propitious opportunity to test these accounts.

We focus on three attitudes in our analysis: views on immigrants, preferences for social spending levels, and opinions on environmental protection. We are specifically interested in understanding particular points of view on these subjects: choosing native Swiss advantage over immigrants with respect to opportunities, preferring support for decreased federal spending on social programs, and desiring more protection of the environment. These opinions relate directly to issues salient in recent Swiss elections. They are also central issues for particular parties and so they are well suited to testing ideas about the connection between certain attitudes and certain partisan preferences. The SVP, for instance, has made issues of immigration a central feature of its political platform (McGann and Kitschelt 2005). The Radicals’ ideology is economic liberalism with a preference for diminished government regulation and spending, and the main raison d’être of the Green party is to promote environmental protection (see Hug and Schulz 2007; Kriesi and Trechsel 2008). If parties are indeed shaping attitudes, the SVP, Radicals and Greens should be most closely affiliated with shifts toward anti-immigrant, anti-spending and pro-environment views, respectively.

With respect to attitude stability across issues, existing work leads us to expect that different kinds of attitudes should display different patterns. The most stable, according to existing research, should be views on immigrants. Studies of lifelong stability in attitudes point to the unusually static nature of racial and ethnic attitudes, which tend to form and crystallize early in life (Sears and Funk 1999). As a core value, environmentalism should be the next most stable over time at the individual level (Inglehart 1997). The least stable of the three should be spending ideas. Economic preferences such as support for government social programs, are the most likely to be updated over time (Brooks and Manza 2008). But given the high level of electoral volatility that characterized the years of the SHP survey, we expect a significant instability for all three issue areas from year to year.

Data and Methods

In most waves of the survey, the SHP asks individuals about their views on several important political issues. These waves are 1999–2009 (annual), 2011 and 2014. The relevant questionnaire items read as follows. The initial primer is: “A number of political goals are questioned; I would be interested to hear your opinion on some of them…”.

Anti-immigrant

“Are you in favour of Switzerland offering foreigners the same opportunities as those offered to Swiss citizens, or in favour of Switzerland offering Swiss citizens better opportunities?” The response options are: in favour of equality of opportunities, in favour of better opportunities for Swiss citizens. We code this 1 if the final option is selected, 0 otherwise.

Anti-spend

“Are you in favour of a diminution or in favour of an increase of the Confederation social spending?” The response options are: in favour of a diminution, neither, in favour of an increase. We code this 1 if the first option is selected, 0 otherwise.

Pro-environment

“Are you in favour of Switzerland being more concerned with protection of the environment than with economic growth, or in favour of Switzerland being more concerned with economic growth than with protection of the environment?” The response options are: in favour of stronger protection of the environment, neither, in favour of stronger economic growth. We code this 1 if the first option is selected, 0 otherwise.

For each variable, through our coding we isolate one specific response to highlight while collapsing the other categories. We do this to gain precision in our analysis by examining only one particular stance. The drawback is that we lose information on the other side of the spectrum. To be sure that this choice does not influence our findings, we replicate each analytical step with variables that reflect the full spectrum of response options. The patterns we present below are not substantively changed. Importantly, the collapsed, dichotomous coding that we use in the presented analysis yields conservative estimates of instability because they do not capture shifts within the “0” category over time. We interpret them with this in mind.

We also examine patterns in party support over time. In each annual wave (1999–2014) the SHP records party preference through the question, “If there was an election for the National Council tomorrow, for which party would you vote?” From this item we create a series of dichotomous variables to indicate support for each of the five main parties in modern Swiss federal elections. These are (roughly from left to right): the Green Party, the Social Democratic Party, the Christian Democratic People’s Party, the Radical Party,Footnote 1 and the Swiss People’s Party.

We also include a number of control variables in our models to offer a more detailed and precise analysis. These are Education level, Age and Female. These variables are derived from literature on attitude change in general and attitudes on immigration, spending and the environment more specifically. For instance, young people are more unstable than their elders in their political views (Alwin and Krosnick 1991). Women and the highly educated are most likely to hold anti-immigrant views (Fetzer 2000; Hainmueller and Hiscox 2007). Older citizens are less concerned about the environment (Inglehart 1997), and women tend to be more supportive of social spending than men (Blekesaune and Quadagno 2003; Funk and Gathmann 2006). While these studies provide guidance, little work examines shifts in these attitudes over time; our analysis provides uncommon insight into how these viewpoints develop.

Because we conduct this analysis with an eye toward isolating the impact of partisan preferences on attitude shifts, we include a lagged dependent variable in each model. To further subject the partisan thesis to a tough test, we include a left-right political ideology variable, Ideology. The highest values represent the most right-leaning position. These steps set up a high hurdle for partisan effects to appear in the results. Finally, we include a dummy variable for each canton to address the highly decentralized nature of the Swiss party system (Ladner 2001), and we cluster the observations by household number to address the non-independence of observations inherent in a household survey.Footnote 2

With respect to our methods, the descriptive correlations we report below are simple bivariate phi coefficients (in Stata 11), which are suitable for estimating the ways that two bivariate variables relate to each other. The statistical models are logit models that include a one-year lag of the dependent variable. This makes it possible to establish the factors predicting attitudinal position net their attitudinal position in the previous year. Functionally, this captures individuals who adopt the specific attitude of interest during the course of a particular year (since the previous wave of the survey). It also captures individuals who move away from a particular point of view. These models provide insight into the factors that distinguish individuals who hold a particular opinion (about immigration, the environment or social spending) from those who do not, net their previous year’s choices. They are therefore between-group (or inter-individual) comparisons that incorporate a dynamic component from 1 year to the next.

Descriptive Findings

From year-to-year, these three attitudes show different levels of stability. For this step in our analysis we utilize all respondents who answer the relevant questions in two consecutive years of the survey. This gives us approximately 50,000 observations.Footnote 3 The waves represented are 1999 through 2009. Later waves are not captured in this step of the analysis because the attitudinal questions become less regularly asked in the most recent waves of the survey. The correlation (phi) between support for Swiss advantage over immigrants at time t and the same variable at time t-1 is .54. The parallel correlation for environmental protection is .46; for anti-spending attitudes it is .44. These numbers point to a rather high level of instability overall, and in relation to each other they align with the expectations drawn from past work on attitudinal stability. Immigration attitudes are the most stable over time, environmentalism is the next most stable, and economic preferences are the least stable. With respect to individual-level shifts from year to year, the Swiss change their minds rather frequently, but they do so in predictable ways.

How does this compare to stability or instability in party choice? For our investigation into partisan preference over time, we use the same respondents (about 50,000 observations) from the same waves as we did to estimate year-to-year correlations in attitudes. Moving from left to right, the year-to-year correlation is .49 for the Greens (to refresh the memory, this is the correlation between Greens at time t and Greens at time t-1), .66 for the Social Democrats, .59 for the Christian Democrats, .59 for the Radicals and .63 for the Swiss People’s Party (see also Kuhn 2009). These figures reveal more stability in partisan preference as compared to the attitudinal stances. The exception is the Green party, which is the least stable partisan choice, and it is less stable over time than are immigration attitudes.

Another consideration is whether the prevalence of people changing their minds on key issues is increasing. Given the high level of electoral flux in Swiss politics, it is important to establish whether instability is rising or declining. For this step, it makes sense to examine only those respondents who participated in the survey in all sixteen available waves of the survey.Footnote 4 Fig. 13.2 details the patterns for the three attitudes of interest over time using the 1999–2009 waves and those 1580 individuals in the full panel. Each dot on the figure represents the phi correlation between a particular variable at time t and that same variable at t-1 (for instance Anti-immigrant in 2000 and Anti-immigrant in 1999). Over time we see that for each of these issues, people’s views are stabilizing across the years of the survey. This relative stability in the later 2000s (decade) as compared to the early 2000s continues into the later waves of the panel. Though we cannot establish year-to-year correlations for years since 2009, we fill in the blanks a bit using the 2011 and 2014 survey waves. For Anti-immigrant views the correlation between 2011 and 2009 is .61; between 2014 and 2011 it is .60. For anti-spending attitudes the correlation between 2011 and 2009 is .47; between 2014 and 2011 it is .43. And for pro-environmental views the correlation between 2011 and 2009 is .53; between 2014 and 2011 it is .51. These are the same individuals as those represented in Fig. 13.2, so we can say that attitudes toward immigrants and to a lesser extent the environment in recent years are much more stable than they were at the start of the survey.Footnote 5 The outlier is spending attitudes. The year-to-year stability gained in this issue area from 1999 to 2009 seems to have weakened more recently. If there is one attitude that is still in flux at the individual level, it is spending opinions.

Models

What factors account for attitudinal change over time? In other words, who is most likely to shift to a position of anti-immigrant, pro-environment or anti-spending? Furthermore, what is the role of partisan preference in promoting adoption of these attitudes? Table 13.1 presents six models of partisanship and political attitudes: models 1 and 2 focus on the effects of SVP partisanship on anti-immigrant attitudes, models 3 and 4 focus on the impact of Green party support on pro-environment attitudes, and models 5 and 6 focus on Radicals support and anti-spending attitudes. Each model includes canton fixed effects. Odds ratios represent relationships of interest: values less than one indicate a negative relationship, greater than one a positive relationship. An even 1 indicates no impact at all.

The first two models estimate the impact of support for the SVP on a desire for Swiss advantage over foreigners – net their desire for Swiss advantage over foreigners in the previous year. We find that the odds of shifting from 0 to 1 on this variable are nearly doubled for those who support the SVP as compared to those who do not. This corroborates an account of attitudinal change that is guided by partisanship. In model 2 we also see that Social Democrats and Greens are less likely to adopt anti-immigrant attitudes, though substantively the effect is weaker than that of SVP preference.Footnote 6 There is no effect of Christian Democrat or Radical partisanship on shifting toward an anti-immigrant position. Education keeps people from adopting a preference for Swiss; age, female and rightist ideology promote this change.

Models 3 and 4 present the results for pro-environment attitudes. Green party supporters are substantially more likely to adopt pro-environment views – the odds of moving from a 0 to a 1 double for Green partisans compared to others. Unlike other attitudes, the effect of partisanship is much weaker for the other parties and only supporters of the Radicals are slightly less likely to adopt pro-environment views. This makes sense given than economic growth is put forth as the opposing goal in the survey question about environmental protection. While Social Democratic and SVP partisanship are statistically significant, the effects are substantively minimal. Overall, these models point to a strong influence of the Green party on pro-environment attitudes. Education, age and rightist ideology make this shift less likely; female makes it more likely.

Models 5 and 6 present the results for aversion to social spending by the government. These attitudes offer the clearest divide along ideological lines with conservative party supporters more likely to favor a reduction in social spending and liberal parties less likely to favor a reduction in social spending. Nevertheless the expectation that the Radicals would exert the strongest effect on economic attitudes is not borne out – while the odds of Radical partisans favoring a reduction in spending is about 35% greater compared to the others, the odds of SVP partisans favoring a reduction is about 65% greater.Footnote 7 This result surprises us. We discuss it in our concluding section below. Green and Social Democrat supporters are much less likely to adopt an anti-spending perspective. Rightist ideology increases the odds of shifting to an anti-spending position; being well-educated, older and female reduces the odds of this shift.

Interestingly once prior attitudes and partisanship are accounted for the effect of ideology is modest in all of the models. For ideology to have an impact similar to SVP partisanship on anti-immigrant attitudes an individual would need to become substantially more conservative, moving about 3–4 positions on the left-right scale. Similarly, for pro-environment attitudes an individual would need to move at least 5 positions to the left to have an effect comparable to Green partisanship. Even on attitudes toward social spending, which arguably maps closest to the left-right scale of all the attitudes, the effect of ideology remains modest compared to partisanship. This supports the role of political parties in shaping attitudes on specific issues and suggests that those attitudes are not simply extensions of an individual’s ideological leaning.Footnote 8

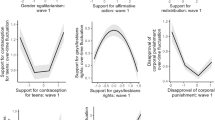

We take one additional step in this analysis. Interaction models enable us to establish the age at which people’s attitudes are most shaped by partisanship. This is important to examine for two main reasons. First, it serves as a robustness check. If in our models we are, indeed, capturing influence by parties, then this effect should be strongest for young people. Young citizens are the most malleable; their entry into the electoral system takes place during “impressionable years.” As such, our narrative stands to be further refined by considering whether this is the case. Second, an interest in stability and change should consider not only past trends but likely future ones. Examining how Swiss citizens at different ages respond to partisan cues can help to predict future patterns in political behavior.

Three lagged dependent variable logit models provide the relevant evidence. They parallel models 1, 3, and 5 in Table 13.1 with the addition of an interaction between SVP support and Anti-immigrant attitudes, Greens support and Pro-environment attitudes and Radicals support and Anti-spend attitudes, respectively. We use lincom in Stata to estimate interactive effects. Full models are available from authors.

Figure 13.3 presents the identified patterns for party influence on shifts in key attitudes across ages. Each interaction coefficient is statistically significant at the .05 level. Starting with views on immigrants, we see that the impact of SVP support is strongest among those who are young. The odds of shifting to an anti-immigrant position are about doubled for SVP supporters who are twenty-five and younger. They are increased by 50% among those in their seventies. The same slope is identified for spending attitudes as they are shaped by support for the Radicals, though the effect over all is weaker.Footnote 9 For the youngest of respondents, the odds of preferring less social spending are 50% higher among those who choose the Radicals as compared to those who do not. But at the highest age range this effect is about null and is not statistically significant. The outlier in this figure is environmental attitudes. The impact of Green party support on a preference for environmental protection actually strengthens across age groups. This implies that environmental opinions develop quite differently than do immigration and spending attitudes. We consider this below.

Discussion

Our theoretical point of departure for this chapter was contrasting narratives about partisan choice and attitudes. The classic model of electoral behavior in a democracy depicts a partisan choice motivated by policy preferences. A competing view posits that parties shape people’s views on key issues. While each plot likely tells part of a valid give-and-take story of citizen behavior in democratic systems, we pursue a better understanding of how the latter process works. By studying political behavior at the individual level in Switzerland, where the electoral system has been in relative disarray for over a decade, we gain new insights into the relationships between partisanship and attitudes. In this concluding section we summarize our findings and consider the extent to which previous research did or did not prepare us for various aspects of our results.

We find that there has been a great deal of instability from 1 year to the next in people’s views on immigrants, the environment and spending. The disorder of the electoral system previewed this finding. But these attitudes vary with respect to how stable they have been. Existing research predicted the relative patterns: immigration attitudes are the most stable, followed in succession by environmental attitudes and then spending preferences. For all three of these issues, attitudes appear to be stabilizing across the years of the survey; most of all for immigration attitudes, least of all for spending views.

We also find evidence that partisanship shapes people’s stances on key political issues. The most convincing account can be drawn from our findings on immigration attitudes. Supporting the SVP is strongly associated (more than any other party) with a shift to preferring Swiss advantages over opportunities for immigrants. As attitudinal change theories would predict, the most influence-able are the young. We interpret our models to mean that a person who likes the SVP will adopt key aspects of the party program into their own set of policy preferences over time. The rise of the SVP, therefore, can be at least partly attributed to the party’s ability to persuade voters to agree with them on matters associated with immigration. This is an important contribution to our understanding of electoral change in Switzerland, specifically the rise of the SVP.

The account of shifts in environmental and spending attitudes is less clear-cut. For the environment, the Green party plays a chief role, but its influence does not operate as attitudinal change theories would predict. Notably, the impact of Green party support on a pro-environment stance is strongest among the oldest, as opposed to the youngest respondents. Inglehart’s value change thesis posits that environmental attitudes (among other post-materialist values) are strongest among younger generations due to the conditions under which they were raised. Young people’s for the environment, therefore, would pre-date their entrance into the electoral process. Elder citizens may be the ones who need persuading, and the Green party picks things up from there.

As for opinions on spending, the Radicals have a strong effect on the choice to desire less social spending, but the SVP’s effect is—unexpectedly—greater. We suspect that the stronger impact of SVP than Radicals support on anti-spending views is a function of SVP rhetoric about government spending on immigrants. Past work shows that European publics consider immigrants to be particularly undeserving of welfare spending (van Oorschot 2006). This result might also be a function of SVP preference for devolved spending at the cantonal and communal levels since the survey question specifically asks about confederation spending. Both possible interpretations signal that the issue of spending may have morphed over the years in the public dialogue and the public mind.

Overall, our analysis tells a story of significant change but increased stability in recent years. Looking ahead, we predict greater tumult in citizen views on public spending. We also anticipate that the youngest voters will continue to be influenced by the SVP on immigration attitudes. In terms of theory building in political science, our findings signal that greater attention to the socializing role of political parties will enhance our understanding of democratic citizens’ political behavior.

Notes

- 1.

In 2009 the Radical party merged with the smaller Liberal party (technically now FDP-the Liberals). The SHP provides separate support for each party even after the merge. We find that combining these parties’ followers into one group as of 2009—as opposed to keeping Radicals supporters separate—does not influence the results of statistical models. Therefore, for the sake of consistency across waves, we do not include in the statistical analysis support for the much smaller Liberal Party or for the combined partisan entity.

- 2.

The results we report below are robust to inclusion of additional covariates. These include: occupation, income, religion and political interest.

- 3.

Observations throughout this analysis are person-years.

- 4.

If we open this up to include all individuals from all waves who participated in two consecutive waves of the survey, the basic longitudinal patterns are the same. Though the level of year-to-year stability in general is slightly lower.

- 5.

Support for each of the major parties in Switzerland also proves to be stabilizing throughout the course of the survey. Replicating the descriptive presentation for attitudes displayed above in Fig. 13.2, we find that the year-to-year stability at the end of the sixteen waves (2013 X 2014) is approximately .10 higher than it was in the earliest waves for three of the parties (1999 X 2000): SVP, Christian Democrats and Social Democrats. Stability in support for the Greens and the Radicals increased only about half as much as for the other parties. This is for those individuals who were in the survey in all waves, just as described for Fig. 13.2. All difference in year-to-year stability from the earliest to the latest waves of the survey are statistically significant. Results available from authors.

- 6.

The reference category for partisanship in models 2, 4 and 6 are supporters of parties not listed in the model, those who would prefer a particular candidate instead of a party, those who “don’t know” who they would vote for, and those who would not vote if an election were tomorrow.

- 7.

Dropping the ideology variable only widens the impact gap between the SVP and Radicals.

- 8.

One might suspect that these models do not capture stable partisanship’s effects; perhaps one changes one’s views and then adopts the relevant partisan preference. To be more confident in our interpretation of partisan effects on attitudes, we tried a number of different configurations such as introducing lagged partisan variables and controlling for supporting the same relevant party in both t and t-1. None of these changes resulted in substantively different findings.

- 9.

In response to Table 13.1, Model 6’s finding that SVP support is the chief predictor of shifting to an anti-spend position, we also tested the interactive effect of SVP and age on spending views. The effect is not statistically significant.

References

Alwin, D. F., & Krosnick, J. A. (1991). Aging, cohorts, and the stability of sociopolitical orientations over the life span. American Journal of Sociology, 97(1), 169–195.

Blekesaune, M., & Quadagno, J. (2003). Public attitudes toward welfare state policies: A comparative analysis of 24 nations. European Sociological Review, 19(5), 415–427.

Brooks, C., & Manza, J. (2008). Why welfare states persist: The importance of public opinion in democracies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. New York: Wiley.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

Fetzer, J. S. (2000). Public attitudes toward immigration in the United States, France, and Germany. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Funk, P., & Gathmann, C. (2006). What women want: Suffrage, gender gaps in voter preferences and government expenditures. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=913802 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.913802 . Accessed on 5 Sep 2016.

Hainmueller, J., & Hiscox, M. J. (2007). Educated preferences: Explaining attitudes toward immigration in Europe. International Organization, 61(2), 399–442.

Hug, S., & Schulz, T. (2007). Left-right positions of political parties in Switzerland. Party Politics, 13(3), 305–330.

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and post-modernization. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kriesi, H., & Trechsel, A. H. (2008). The politics of Switzerland: Continuity and change in a consensus democracy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Kuhn, U. (2009). Stability and change in party preference. Swiss Political Science Review, 15(3), 463–494.

Ladner, A. (2001). Swiss political parties: Between persistence and change. West European Politics, 24(2), 123–144.

Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2000). Three steps toward a theory of motivated reasoning.” Ch. 9 in. In A. Lupia & M. D. McCubbins (Eds.), Elements of reason: Cognition, choice, and the bounds of rationality (pp. 182–213). New York: Cambridge University Press.

McGann, A. J., & Kitschelt, H. (2005). The radical right in the alps: Evolution of support for the Swiss SVP and Austrian FPÖ. Party Politics, 11(2), 147–171.

Miller, W. E. (2000). Temporal order and causal inference. Political Analysis, 8(2), 119–146.

Sears, D. O., & Funk, C. (1999). Evidence of long-term persistence of adults’ political predispositions. Journal of Politics, 61(1), 1–28.

Sniderman, P. M., & Levendusky, M. S. (2007). Chapter 23: An institutional theory of political choice. In R. J. Dalton & H. Klingemann (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political behavior (pp. 437–456). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office. (2016). Available at http://www.bfs.admin.ch. Accessed Feb 2016.

Van Oorschot, W. (2006). Making the difference in social Europe: Deservingness perceptions among citizens of European welfare states. Journal of European Social Policy, 16(1), 23–42.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

<SimplePara><Emphasis Type="Bold">Open Access</Emphasis> This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.</SimplePara> <SimplePara>The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.</SimplePara>

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fitzgerald, J., Jorde, C. (2018). Dynamic Political Attitudes in Partisan Context. In: Tillmann, R., Voorpostel, M., Farago, P. (eds) Social Dynamics in Swiss Society. Life Course Research and Social Policies, vol 9. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89557-4_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89557-4_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-89556-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-89557-4

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)