Abstract

This case study aims to study and analyse what appears to be a successful co-created educational policy—the ‘Finnish National Curriculum 2016’. The author wished to understand the factors behind the success of the curriculum process, how ownership was created during the process and what school principals and other education professionals think about the curriculum content, as well as the processes and methodology. Questions abound. What are its strengths and weaknesses and does the curriculum pull schools closer towards their purpose? The Finnish education system has been celebrated as a twenty-first century global success story—what role does a national curriculum play in this story and how does it take the education system closer to enabling sustainable well-being? Does the progressive value-base and content of the curriculum successfully transfer to the classroom?

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Finland

- Curriculum

- Educational policy

- Transversal competences

- Teacher participation

- Co-creation

- Digitalization

- Sustainability

Welcome back to school. During the summer a revolution happened. This autumn the new national curriculum will become effective in Finnish schools. First at K-12 education and then at secondary school. Every school interprets the curriculum in their own way. The basis of the curriculum is national, municipalities do their own alignments and schools decide on the details. (Aalto 2016, translated by author)

Following the publication of an article in Helsingin Sanomat on August 6, 2016, many Finnish teachers reacted to the news piece saying that a ‘revolution’ was too big a word to accurately describe the effects of the new national curriculum. That said, Finnish schools undeniably faced something new starting in the autumn of 2016. Janne Hirvonen, a school principal from Rautjärvi, in Eastern Finland, described the curriculum thus, ‘This is an enormous change. Our aim (at Rautjärvi school) is that the everyday life of our school will change so that it reflects the new curriculum’ (Janne Hirvonen, personal communication, May 2016).

The National Curriculum of Finland

Finland’s national curriculum guides the nation’s whole education system. It sets the framework for school work by defining the values and objectives for all Finnish schools. There are no school inspections or national achievement tests covering entire age groups (though there are sample-based national achievement tests for two or three of the basic education subjects every year). This is why it is perceived to be important to have a shared framework. The curriculum defines the main objectives for different subjects and inspires the use of new kinds of learning methods (and later in this chapter you can read more about project-based learning and its aim of achieving a more collaborative learning). Despite the common framework offered, there remains considerable freedom for individual schools to interpret the curriculum as they wish. The 500-page document consists of values, objectives and general principles that number around 100 pages. The rest of the document covers the subject syllabi.

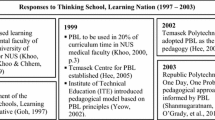

The origins of the national curriculum date from 1970 when the national curriculum committees report was released. The curriculum is now managed by the Finnish National Agency for Education (EDUFI) which leads the curriculum development work every ten years.1 The first curriculum, led by the EDUFI, was created in 1985 after which it was renewed in 1994 and 2004, with the latest work started in 2012. Over the course of the latest development cycle, the curriculum evolved from a fairly typical bureaucratic process to a leading example of co-created public policy. Hundreds of professionals participated in the 2.5-year long curriculum design process. The national core curriculum was completed at the end of 2014, with the local curriculums ready in 2016. The new curriculum became effective in August 2016.

This case study aims to study and analyse what appears to be a successful co-created educational policy—the Finnish National Curriculum 2016. The author wished to understand the factors behind the success of the curriculum process, how ownership was created during the process and what school principals and other education professionals think about the curriculum content, as well as the processes and methodology. Questions abound. What are its strengths and weaknesses and does the curriculum pull schools closer towards their purpose? The Finnish education system has been celebrated as a twenty-first century global success story—what role does a national curriculum play in this story and how does it take the education system closer to enabling sustainable well-being? Does the progressive value-base and content of the curriculum successfully transfer to the classroom?

A Co-created National Policy

What became clear during the research for this case study is that the Finnish national core curriculum is more about the complex process of creation than it is about the actual final product. Decade after decade, the curriculum process has developed into a more open and inclusive process. The now retired lead of the curriculum process, Irmeli Halinen, has described the national core curriculum and the local curriculums (based on the national curriculum) as having been created through open, interactive and co-operative processes. The curriculum work is seen as an ongoing dialogue and learning cycle that helps professionals in the education field identify the issues to be improved and promote the commitment of all stakeholders in the curriculum process. The curriculum also sets the agenda for education at a societal level; its core purpose, objectives and principles.

Arja-Sisko Holappa, the Counsellor of Education from EDUFI, is of the opinion that even though the groundwork is done by the Agency, it is understood that the best ideas to develop education generally do not come from the administration. This understanding explains why it is crucial to see the curriculum reform as a national learning process for the whole community of educators and other professionals in the field. The curriculum is based on legislation, and the local curriculums are binding for teachers. But when professionals are part of the process of designing the curriculum, there is no need to use coercive power. The Basic Education Act and Decree in Law sets the base for curriculum work. The Finnish parliament is responsible for defining the general national objectives and distribution of lesson hours for basic education (Arja-Sisko Holappa, personal communication, May 23, 2016).

The experts interviewed for this case study commented that the curriculum reform allows professionals from the field of education to take time and reflect on the big questions facing education. For example: what is the curriculum’s purpose? What is the role of a student, a teacher and society in terms of learning? What should the future look like and what is the role of professionals in the system?

Even though the curriculum is binding, there are no sanctions or other forms of punishment if schools or teachers do not adhere to it. To that end, the level of interest and commitment to bring the objectives of the curriculum to the classroom itself vary across different parts of Finland, as well as between different teachers working in the same school (Table 13.1).

Irmeli Halinen, who was the Head of Curriculum Development, describes the curriculum development as a ‘whole of society’ project with comments contributed by many stakeholders across Finnish society. Occasionally, some of the approaches proved surprising, like the Finnish police who wanted to give their support by writing chapters about safety and security. Three official commenting phases were open for anyone to comment. At the same time, EDUFI asked education authorities and schools to comment on the document through a survey planned for the precise purpose. Schools were also encouraged to include parents and students’ feedback.

The goal of EDUFI was to make all of the stakeholders ‘experts’ of the curriculum. During the process, it was noticed that a curriculum roadmap was needed so that it would be easier for municipal education authorities, principals, teachers and other education specialists to participate in the project which ultimately spanned across more than two years. One of the most important stakeholder groups were the municipal education managers who were responsible for writing the local curriculums. Local curriculums are based on the guidelines of the national curriculum, but acknowledge the local features, geographic-related influences and other specific needs of the regional demographics.

The author asked Arja-Sisko Holappa about the purpose of a curriculum. She did not have to think about the answer for long:

They exist to secure equal education for the whole of Finland. The curriculum is a way to guide the whole system and a tool for securing equality and providing professional development for teachers. But what has to be acknowledged is that there is the official, written curriculum, and then there is the lived one and the hidden one that influence cultural norms. (Arja-Sisko Holappa, personal communication, May 23, 2016)

In Sweden by comparison, the latest national curriculum dates back to 2011 at the time of this writing. The curriculum carries a strong emphasis of creating more equal schools across the country. Sweden has had challenges with respect to the pupils learning outcomes in general, and the latest curriculum is aimed at strengthening the steering of the schools at a national level.

The 2016 Finnish National Curriculum—What Makes It Special?

The new national curriculum of Finland is a progressive document. This can be seen in the value base set for Finnish education, how ‘wellbeing’ is defined in a holistic sense and how research has been utilised in the process of creating the curriculum. In practice, these are reflected in how transversal competences are being implemented in schools and how assessment practices are changing to support every child’s individual strengths.

The 2016 curriculum work started with the understanding that the impact of globalisation and the need for a sustainable future were reshaping the fundamentals of schooling. It was also understood that the skills and competences needed to succeed in society and working life were also dramatically changing and thus education, pedagogy and the role of the school itself needed to change in relation to these ongoing global shifts. In an article by EDUFI entitled ‘Making Sense of Complexity of World Today: why Finland is Introducing Multiliteracy in Teaching and Learning,’ the need to address these shifts within the curriculum was explained:

The increased need for transversal competences arises from changes in the surrounding world. In order to meet the challenges of the future, there will be much focus on transversal (cross-curricular) competences and work across school subjects. As structures and challenges of doing, knowing and being are changing essentially in our society, it requires us to have comprehensive knowledge and ability. Competences include a vision of the desirable future and the development of both society and education. (Halinen, Harmanen, & Mattila 2015, p. 139)

The national curriculum that was implemented in Finland in 2004 needed to be updated. The reasons for this are many, varied and include the following: subjects were too unattached, objectives for education and learning needed clarification, learning environments and methods had changed, student’s well-being needed more attention, more diverse assessment methods were needed, the collaboration between school and homes had changed, and finally, the national curriculum of 2004 no longer supported the future challenges of schools and learning to the standards and levels required.

Irmeli Halinen suggested that the key questions to support the curriculum work were: what will education ‘mean’ in the future? Furthermore, what kind of competences will be needed and what kind of practices would best produce the desired results in terms of both teaching and learning?

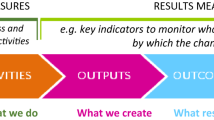

According to Halinen, the new national curriculum was built upon the core strengths of the Finnish education system, strengths that include a culture of co-operation and trust, as well as competent, committed and autonomous teachers, and an already well-functioning curriculum process. The starting point, from the view of the schools themselves, was to strengthen the pupils’ sense of coherence and to support them to take responsibility for their actions and choices that shape their (and therefore our) future (Fig. 13.1).

The defined values for the Finnish national curriculum are:

-

Uniqueness of every pupil and high-quality education as a basic right

-

Necessity for a sustainable way of living

-

Humanity, culture and civilisation, equity and democracy

-

Cultural variety as richness

The focus of the curriculum reform has been broken down into three key themes:

-

Rethinking learning: learning to learn in dialogue with others, importance of feelings, experiences and ideas and their joy of learning

-

Rethinking the school culture and the relationship between the school and the community

-

Rethinking the roles, goals and content of school subjects: moving towards transversal competences to support the identity development of a child and the ability to live in a sustainable way.

To summarise, the key challenges and changes arising from the curriculum from the school’s perspective are:

-

Developing school cultures to support curriculum values and goals and developing schools as real learning communities

-

Students’ role is more active and inclusive

-

Teachers’ role changes; reduced lecturing from a podium

-

Technology and digitalisation; e-books, coding and digital learning platforms more strongly implemented into schools’ eco-system

-

Project-based and multidisciplinary learning modules with transversal competences at least once a year in all schools and all grades.

-

Shifts towards self-assessment and peer-assessment (assessment as learning) and learning how to give feedback.

What Does the National Curriculum Mean for Schools?

The national curriculum defines seven transversal competences that need to be developed in all schools in Finland. The transversal competences reflect competence definitions from different institutions and organisations globally. These have been adjusted to the best Finnish educational traditions. There is clear inspiration from the European Union’s key skills (2005), OECD’s key competences (2005) and work life’s key competences (IFTF 2011). The background of the transversal competences lies within a wider framework of future skills and competences (Luostarinen and Peltomaa 2016, p. 50).

Transversal competences and project-based learning:

From the point of view of a teacher, the biggest change that the new curriculum brings is that the overall goal for basic education focuses on the learning of transversal competencies. This means that knowledge, skills, values, attitudes and will are seen holistically and it is understood that all of these have a fundamental impact on learning. Personal growth, studying, work life and being a citizen require know-how that surpasses the limits of individual subjects.

One notable way to practice and enhance transversal competences is through project-based learning. This means studying various real-world phenomena in groups or teams and making sure that through these phenomena that multiple subjects are touched upon. Katariina Salmela-Aro, Professor, Department of Education, University of Helsinki, has studied student’s attitudes towards school and written about ‘boredom’ felt towards school. The group of students who feel often bored at school are those young people who feel that they do not get enough challenges at school and also that the school system and the rest of their lives are disconnected.

Teamwork, an integral part of project-based learning, also gives children a chance to practice their interaction skills to help them identify, develop and exploit their strengths. According to the curriculum, each student has to have a project-based learning module at least once a year. What this means more concretely is to be more clearly defined by individual municipalities.

A project-based approach also significantly adds co-operation possibilities between teachers, which is another objective of the new curriculum. The underlying philosophy in project-based learning is that studying strictly unattached subjects is artificial and does not prepare children to both face and deal with real-world challenges. This does not have to mean solving highly complex challenges like climate change and poverty, but rather everyday life situations that require an understanding of how different systems relate to each other.

One year ago, the author participated in an event hosted by a group called Systems Thinking Applied. The purpose of the event was to experiment with what project-based learning actually means. During the event, the organisers acknowledged that project-based learning and teaching raises a lot of interest as well as puzzlement among teachers. The question of how you can teach project-based learning if you have never tried it yourself was one motivating factor behind the event (Honkonen and Lehmuskoski 2015).

To that end, people at the event came up with different phenomena that they were interested in and then organised themselves into small groups based on interest to research these phenomena further. Some findings from this experiment were:

-

No one has the right answers: neither the students, nor the teacher! Project-based learning then, means the willingness to act with uncertainty. More than teaching, it is about guiding a learning process.

-

Scoping the phenomena is challenging. Hypotheses or propositions that are too wide in scope can lead to individuals who are unmotivated. Conversely, a too narrow scope for a project can lead to a situation where valuable insights are left out.

-

Difficult phenomena are easier to understand when you can connect them to your everyday life. (2015)

The Ritaharju school in Oulu, Finland wanted to experiment with project-based learning for a week as a part of Sitra’s New Education Forum in 2015. The principal of Ritaharju school, Pertti Parpala, desired project-based learning to be tightly interlinked with a bigger change in school culture that needs to take place in Finnish schools. ‘Co-operation, openness and trust among teachers are central for developing a school,’ states Parpala (Pertti Parpala, https://www.sitra.fi/blogit/viikko-ilman-luokkarajoja/).

At Ritaharju, the pupils got to choose phenomena they wished to work with during the experiment week. It is argued here that this should be the starting point for project-based learning in order to motivate the pupils. Of course, there can be some guidance or overarching theme to further help or direct the pupils. At Ritaharju, the eighth-graders needed to choose a phenomenon related to Europe and more precisely to equity, sustainable development, media literacy, multi-literacy and inclusiveness. Examples of phenomena that the eighth-graders chose to study:

-

Auschwitz and Birkenau

-

Food culture in Germany, Finland, Spain and Turkey

-

Historical eras of European art and music

Outi Ruotsala, the principal and teacher at Raattama school in Lapland, states that in Kittilä municipality, the theme of the first project-based learning module is ‘I am a Kittilä resident’ (Outi Ruotsala, personal communication, August 30, 2016). As the module title suggests, the young pupils concentrate on researching what it means to be a Kittilä resident with the help of their own experiences. All of the schools in Kittilä will have the same theme and at the end of the project-based learning module there will be an event for all schools where the work the children have completed will be presented. Ruotsala is planning to use photography with the pupils, but she adds that the learning module needs to be planned together with the children as the new curriculum suggests.

At Simpele school, located in Rautjärvi in Eastern Finland, the theme of the first project-based learning module will be ‘Finland 100 years,’ according to the principal Janne Hirvonen because Finland is celebrating its 100th Anniversary of Independence in 2017. As a second option, Simpele had also thought of a theme focused on local issues similar to the school in Lapland. Likewise, Laihia school in Western Finland has also chosen a local theme for its first project-based learning module.

Aki Luostarinen and Iida Peltomaa wrote in their book National Curriculum—Implementing Recipes for Teachers 2016 (the author’s English translation), that using transversal competences as the base for education has two grand goals. Firstly, one cornerstone is to support student’s growth as a human being by finding ones’ own place and strengths in life. Secondly, it is about growing to become a member of society in its fullest meaning. The overarching goal is to evoke a desire in a student to be part of building a sustainable future. There needs to be competence building to secure that everyone has sufficient knowledge and skills to participate in society’s decision-making and other activities (Finnish National Board of Education 2016; Luostarinen and Peltomaa 2016, p. 49).

Digitalisation

Bringing digitalisation, digital learning methods and coding, for example, more strongly into the school eco-system, is one of the aims of the new curriculum. It is a widely discussed topic more generally in Finnish society. The program of Prime Minister Sipilä’s government that became effective in May 2015 has five key objectives, one of which has to do with education, learning and competences. One of the main objectives is that Finnish schools take a so-called ‘digi-jump’ so that digital learning materials and platforms would be incorporated into wider use. According to a widely cited European Commission report3 on Finland, only every fifth Finnish student uses ICT-technologies daily in school.

The Sipilä administration’s key program has received criticism because the government simultaneously carried out substantial cuts to the overall education budget. There are also commentators suggesting that the current situation appears to be that a school gets iPad’s, but no instruction in how to utilise them in the classroom or do not have any e-books or other materials to support digital learning. Digitalisation in recent years in Finland seems to be both a buzzword and a simplistic answer for everything, and that continues to create irritation and disillusionment for many in the education community.

When interviewing several school principals, they pointed out that focusing on digital learning is one of the key challenges for their school. Principal Ruotsala shared, ‘I have to admit that the world of iPad’s is quite unfamiliar to me, but I see the objectives of the new curriculum as an opportunity for myself also to learn together with the students’ (Outi Ruotsala, personal communication, August 30, 2016). Adds Principal Hirvonen, ‘There’s a couple of teachers in my school who have entirely given up books and use only digital learning materials. For me, it’s no problem to admit that many students are far more competent in using the devices than me and can teach me. For some teachers this is a challenge to admit that a child knows something better than you. They are scared that they lose their authority’ (Janne Hirvonen, personal communication, August 31, 2016).

Assessment

The new national core curriculum supported by Finnish law, states that verbal assessment can be used in grades 1–7. Numerical assessment should be started at the latest at 8th grade. The decision regarding when the numerical assessment begins is made at the local level in municipalities. Progressive Finnish teachers have even promoted the idea of giving up numbered assessments in order to make sure that no student feels they are below standard in certain subjects. The curriculum states:

School affects substantially in what kind of perception students have on themselves as both a learner and a human being. Especially significant is the feedback students get from their teacher.… Good collaboration with parents is part of a good assessment culture… Students and their performance are not compared to each other and assessment does not concern student’s personality, temperament or other personal attributes. (Finnish National Board of Education 2016)

The objectives for an assessment culture are outlined in the curriculum:

-

Encouraging atmosphere that supports all students to ‘have a try’

-

Versatile assessment methods

-

An assessment culture that supports students’ inclusiveness and dialogue

-

Supporting students to understand their own learning and to make the progress they are doing visible to them

-

Ethicality and fairness

-

Using the information that assessment gives to develop teaching

Principal Ruotsala from Raattama School states that after reading the chapter from the curriculum about assessment, its full meaning was still unclear to her. She understood assessment to be about constructing and encouraging feedback that helps the student to move forward in their learning and to recognise their strengths and places for development. However, Ruotsala says, it is extremely important that the joy gained in learning is not ‘killed’ by a number (Outi Ruotsala, personal communication, August 30, 2016).

Sanna Schöning, a principal from Laihia in western Finland, is of the opinion that assessment should not be forgotten, and that now with the new curriculum, new ways of assessment are being implemented. In practice, this means self-assessment, peer assessment and discussions with parents and the child about all aspects of learning and development (Sanna Schöning, personal communication, August 25, 2016).

Becoming Sustainable Citizens

One of the seven defined areas of transversal competences in the curriculum is about learning to live in a sustainable way. Niina Mykrä, Ph.D. researcher and executive director for LYKE-network (a supporting network for nature, environment and sustainable lifestyle education) has analysed the curriculum from the point of view of environmental education. Mykrä found that climate change is mentioned only four times in the entire 500-page document. Still, it has to be acknowledged that in the value base for basic education, it is quite heavily emphasised that eco-social well-being means an understanding of how significant the threat of climate change is for humanity and that learning to live in a sustainable way includes understanding many aspects, with climate change representing one of them.

Former school principal, Counsellor of Education and author Martti Hellström, has analysed the feedback that educators and other interested individuals gave to the Finnish National Agency for Education during the first phase of commenting on the curriculum in 2014. The commentators were supporting the future-orientation and the content descriptions of transversal competences. What was seen as lacking at that point was entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial skills. Sustainable development, environmentalism and global thinking were also seen as areas that needed to be substantially strengthened in the curriculum. Irmeli Halinen, says that these topics were given more emphasis as a result of the opinions expressed during the commenting phase (Irmeli Halinen, personal communication, February 2016).

Niina Mykrä expresses the opinion that, all in all, the curriculum for basic education is excellent from the point of view of sustainable lifestyle and environmental education, since a sustainable lifestyle is seen as the base for critical thinking, education and the whole curriculum. If this curriculum will be implemented in practice, the understanding by the young generation with regards to the preconditions of sustainable future is strong, Mykrä believes (Niina Mykrä, personal communication, February 2016).

Other principals who were interviewed for this case study also said that they appreciated the future-orientation of the curriculum, but when the author asked them what was most valuable for them in the new curriculum, no interviewees mentioned the focus on a sustainable lifestyle. It remains to be seen how the grand goals of the curriculum such as sustainability transfer to everyday school-life.

A Principal’s Thoughts About the New Curriculum

The school principals interviewed for this case study hail from diverse geographical regions of Finland to help achieve a fuller picture of how the national curriculum is perceived in different parts of the country. The distance from Lauttasaari school located in the capital Helsinki to Raattama school located in Kittilä, is around 1100 kilometres. These two schools differ from each other in various ways. At Lauttasaari school, there are more than 800 pupils and it is the biggest K-12 school in Helsinki. At Raattama school, there are 6 pupils and one teacher, Outi Ruotsala, who is also the school’s principal (Fig. 13.2, 13.3).

When the author traveled to Raattama school in the far north of Finland, together with the principal Outi Ruotsala, we saw only one car, the post car. The quietness and peacefulness is astonishing for someone like the author who lives in Helsinki. Raattama has around 150 inhabitants. The main sources of livelihood are reindeer ranches and seasonal work at the nearby skiing centres. During the research the author wanted to find out what the school principals thought about the curriculum process and its contents. Questions, for example, included: how does the new curriculum affect the school work in practice and what does the curriculum mean for the school?

On a beautiful day in May 2016, the author visited Lauttasaari school located on a residential island in western Helsinki. Entering the school yard, the pupils were having their afternoon break and one of the teachers were serving the pupils ice-cream. Everything was so idyllic, that it made the author rather nostalgic for her own school days.

Johanna Honkanen-Rihu, the principal of Lauttasaari school, was feeling relieved. Her school had, just the day before, sent their schools final version of the curriculum to the Helsinki City education department. The process of formulating the curriculum took 2.5 years. Honkanen-Rihu can claim a long career in the field of education, first as a teacher and then as a principal in three different schools in Helsinki. She has participated in all of the national curriculum processes in Finland.

The City of Helsinki education department provided schools with the frameworks and guidelines to help them develop their own school-based curriculum. That said, the teachers at Honkanen-Rihu’s school were a little bit hesitant to start the curriculum work because of the additional workload. Honkanen-Rihu, however, convinced the teachers that the in-depth discussions about the value base of education that the school provides, plus the myriad goals and objectives for learning and other curriculum related matters, would help their school to become a considerably better institution for both learning and teaching.

This seemed to be the case in all of the schools covered in this case study. The principals described a situation whereby due to the heavy workload that the curriculum process created, the teachers were not too eager to start the work. All of the cities in Finland seemed to have a similar working style with regards to the curriculum preparations: each teacher participated in one sub-working group. The theme of the sub-working group was either a school subject or related to the transversal competences or value base of the curriculum. Furthermore, the municipalities had somewhat different resources to invest in the curriculum work. A few municipalities had the financial budget to allow the hiring of a curriculum coordinator.

The process of translation from the national level to a local and even school level creates ownership and investment in the core principles. “The curriculum is something that is built together with your colleagues. Everything we do is based on the curriculum,” comments Honkanen-Rihu (Johanna Honkanen-Rihu, personal communication, May 24, 2016).

Outi Ruotsala from Raattama school, describes the process of creating the local curriculum in rather a different tone: ‘The process itself was quite disorganised. There were several months of meetings that were of no use because no one knew what to do. I was trying to find some instructions from the internet in order to make the work we were doing consistent between different subjects, but I did not find anything. We even had a joke that someone knows what we should do, but they just won’t tell us.’ Despite the difficulties that occurred during the local curriculum process, Ruotsala states that many teachers were enthusiastic about the new curriculum. ‘It is almost like there is now permission to do things differently in school,’ Ruotsala opines (Outi Ruotsala, personal communication, August 30, 2016).

From the authors perspective, it seems that the way in which the Finnish National Agency for Education gave freedom to the municipalities, cities and individual schools to define the curriculum themselves, embodied the spirit of the new curriculum; learning transversal competences to cope and thrive in a complex society and world. That said, teachers seemed to hope for some structure and guidance. They wanted to know that they were doing the right thing and that they were providing equal learning possibilities for every child.

When the author visited Saunalahti school to interview the principal Hanna Sarakorpi, there was a palpable sense of her passion for her work when she spoke about the practices in her school. On the walls of her office she had old Finnish poems that described the uniqueness of every child. The school is located in Espoo, which is a 250,000-strong residential city located next to the capital Helsinki.

Saunalahti school has been the focus of numerous magazines and articles around the globe because of the progressivity of both the architecture and surroundings of the school and the pedagogics. Sarakorpi is of the opinion that the new curriculum challenges every school in Finland to take a new perspective, for example, on the role of the students themselves. The majority of schools are located in small cities and municipalities.2 There are many schools in Finland that have not yet reached the former curriculum cycle objectives, Sarakorpi states (Hanna Sarakorpi, personal communication, May 24, 2016).

School Cultures Support (Or Do Not Support) The Implementation of the Curriculum

This brings this case study to the theme of actually implementing the curriculum i.e., in terms of bringing the policy to life in classrooms around the country. Most teachers support the contents of the curriculum and appreciate the future-orientation of the document, but what they yearn for is support to help with the implementation—namely how to make the curriculum’s progressive principles a reality in classrooms around Finland. Aki Luostarinen and Iida-Maria Peltomaa write in their book that the most essential part of the whole process is that the professionals in the field do not allow the curriculum to become simply just paperwork with no genuine links to the classrooms (Luostarinen and Peltomaa 2016, p. 28).

Hannu Simola, Professor of Education Sociology at the University of Helsinki, writes in his book The Finnish Education Mystery: Historical and Sociological Essays on Schooling in Finland, about the prerequisites for school reform projects to succeed. These are: a majority of the teachers, students and parents in every school have to understand what the reform is about and accept it; the reform has to somehow fit into the school’s institutional practices and traditions, i.e., the reform has to be designed so that the school is able to implement it. The reform also has to open up new societal learning possibilities for the students. Simola adds that only when the school is understood as a historical, political, cultural and social institution, it becomes possible to change it (Simola 2015).

Education manager Tuija Viitasaari, and director of early childhood education and basic education, Kristiina Järvelä, from the City of Tampere education department, state that the culture inside a school defines how the curriculum is perceived and ultimately how it is practiced. The school culture largely determines if the new curriculum is perceived as a threat, an opportunity, something to get excited about or simply another additional burden. The key themes for curriculum work from the school’s point of view are participation, creating a sense of belonging for students, and strengthening the interaction between school and other parts of society (Kristiina Järvelä, Tuija Viitasaari, personal communication, January 2016)

Both Honkanen-Rihu and Sarakorpi highlight the same challenge in curriculum implementation in their schools, as the Finnish National Agency for Education has taken up as a challenge for Finnish schools: strengthening students’ agency and role as learners responsible of their own learning. The teachers’ roles have traditionally been one of control and power. Shifting into a different kind of role of a coach or guide, or less hierarchical style ‘educator’ that supports children to find their own ways of learning requires a considerable amount of ‘unlearning’ and the willingness to change.

Another challenge regarding the teacher’s role, is persuading teachers to work collaboratively in teams. The lack of a team-centric approach may well be seen as a byproduct of high teacher autonomy. That said, the objectives of the new curriculum cannot be met without teachers working together. This, needless to say, will prove to be difficult for those Finnish teachers who are used to doing everything on their own. However, the interviewees for this case study revealed that the teacher’s role and school culture are slowly changing to a more communal way of working. In some schools, teachers already work in pairs or in small groups.

Pedagogical Leadership Needed

Despite the challenges, a distinctive success factor of the curriculum and the Finnish school system, in general, is the bottom-up culture that allows new practices to scale up from individual teachers classrooms to the level of an entire school. In principle, anyone from the community can influence the development of the school.

It is the opinion of principal Sarakorpi that in addition to the co-creative working style of the whole school community, a strong pedagogical leadership is needed at the implementation phase of the curriculum. States Sarakorpi, “The new curriculum challenges teachers and principals to develop a more student-centric school where students really feel like they are valued. This means that we should really put some attention to how children and adults in the school interact with each other” (Hanna Sarakorpi, personal communication, May 24, 2016).

Sanna Schöning is one of the three principals in Laihia, a municipality with 8000 residents. She states, “The effects of the new curriculum on schools is big and thus it has created all the elements of a change process: resistance to change and being skeptical if the new curriculum can bring anything valuable or new to schools.” Schöning continues that her strategy was to give space to these feelings and engage in discussion related to them:

The concepts from the curriculum have to be brought to the teacher’s room step by step. We need to constantly keep up the discussion, otherwise nothing is going to change. It requires a little bit of a shaking up of the status quo and a small amount of anxiety is natural in this process. It means that change is actually about to happen.

We started having conversations about the concepts of the curriculum already early on in the process. I gave teachers homework. We, for example, read various chapters from the curriculum and had pedagogical discussions about the texts. I also asked teachers to present to others what was the most important part of the curriculum to them, and how they wanted to practice it. This exercise really opened up the imagination of the teachers when they heard what their colleagues valued in the curriculum and why. (Sanna Schöning, personal communication, August 25, 2016)

Outi Ruotsala makes a valued point that the culture and community of teachers is different in each school. She has negative experiences from her previous career in certain schools where doing things in a new way were ‘prohibited’. “Everything had to be done like it always had been done. You have to be a real pioneer in order not to give in under the group pressure found in these kinds of schools,” Ruotsala states (Outi Ruotsala, personal communication, August 30, 2016).

Conclusion

Among Finnish teachers there is a joke that if you want to hide a 500 euro note, hide it between the pages of the national core curriculum, because no one ever opens or reads it. The joke is at least partly challenged by the over two-year co-creational process of building the Finnish national core curriculum in 2014. The aim of the Finnish National Agency for Education was to make teachers, principals and other stakeholders experts on the contents of the curriculum.

The national core curriculum has ambition, progressive content and it provides support and momentum for schools to renew or develop their pedagogies and practices. What is now needed is the courage to act and implement, as well as commitment and pedagogic leadership. The school principals’ role in creating the settings for the curriculum to start emerging in practice is important. They need to be enabling leaders who support the whole school community to make a shift toward more collaborative ways of working with the community and society, more collaboration between the teachers and between parents and schools and strengthening students’ agency.

There are variations in terms of the levels of commitment and implementation in schools across Finland and even among cities. Even so, it still has to be acknowledged that when looking at global comparisons, the Finnish school system is uniform and equal. There are still those taboos, like teachers’ fixed working hours, that do not allow for much development work and that creates an incentive for teachers to defend the amount of teaching hours their subject gets in the curriculum. This is especially true in secondary schools. This is not the easiest starting point for project-based learning approaches. That said, it is now defined in the curriculum that every Finnish student needs to have one project-based learning module a year.

The curriculum states that personal growth, studying, work life and being a citizen require know-how that surpass the limits of individual subjects. The overall starting point of updating the curriculum has been a deep understanding of our rapidly-changing society and the demands that this puts on the individuals and society both from the point of view of skills and character. This understanding has created an encouraging atmosphere for discussions of the purpose of schools and education, values and principles.

The curriculum has enabled change to start emerging. One sign of this are increasingly common questions by the media that focus on the teacher’s current and future role—questions that, amongst others, postulate whether teachers are truly allowed to be ‘teachers’ anymore when they have to be more like guides and co-learners. It is likely to be a much-debated question in the years to come and clearly reveals that the implementation of the new national curriculum then, has unequivocally begun to challenge conventions.

Information Box 1: A Teacher Explains: The Curriculum as a Tool for Teachers

School principal Pekka Rokka, now retired, writes in the foreword to his dissertation (2011) about his professional journey with the national curriculums of 1985, 1994 and 2004. In his dissertation he studied, with the help of these three documents, how schools integrated students into society, what kind of civic and societal skills and knowledge students learned, and what kinds of political themes were to be found in the curriculums from different decades. Rokka writes that national curriculums can be considered ‘bibles’ to teachers. “In my daily work as a teacher, I felt that the curriculum is the document that gives ground to my whole work and for my role as a teacher,” (translation by author) he states (Rokka 2011, p. 3).

Rokka posits that the curriculum of 1994 was a radical event in the education field in Finland because each school was supported to produce their own curriculum. This made it possible to do in-depth development work in schools and it made many schools able to take steps forward in their pedagogical and operational practices. Conversely, the curriculum of 2004 felt like a step backwards because it was not as co-creational as the previous one, Rokka explains. The work consisted of reading and commenting on material that others had written, but the deep participation was not there. The core curriculum of 1994 was school-specific, but there was little space for school-specificity in the core curriculum of 1985 and 2004. The core curriculums are guided by pendulous policy since the openness of the curriculum of 1994 was returned back into a more restrictive policy in 2004 (Rokka 2011, p. 9).

Rokka states that individuality, consumer citizenship, entrepreneurship, integration, internationality, the future and encountering the future, emphasis on equity, information technology and technology, effectiveness of media, youth culture, concern for the environment and nature, healthy life and safety awareness, as well as the assessment, development and effectiveness of education, all emerge as central political themes in national curriculums (2011).

Information Box 2: Me & My City—Learning by Doing

Me & My City is a Finnish learning concept for 12-year olds (6th graders) and 15-year olds (9th graders) developed by a former teacher, Tomi Alakoski, and his colleagues. The goal is to give the students the opportunity to develop their understanding of the economy, society, working life and entrepreneurship and transitioning to a circular economy and to strengthen their preparedness in these areas. Me & My City has operated for since 2010 in different cities in Finland. During that time around 250,000 students have visited Me & My City reaching around 75% of the 6th graders and around 40% of the 9th graders in Finland. In 2017 Me & My City started a big collaboration with the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra. Me & My City concept is updated so that it simulates the kind of sustainable practices needed in the future societies. In this circular economy and sustainable business models are emphasized.

Me & My City is organised by the Economic Information Office (TAT) and funded by the Ministry of Education, The Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra, companies, municipalities and foundations. The learning environment created by Me & My City simulates a city with a post office, city hall, supermarket, local newspaper and businesses. The goal is to give children a learning experience that is rooted in the everyday-life practices and operations of society. For one day, the young students work in different positions in the city and have tasks that they are responsible for. The pupils generate an income from their job which they can use to purchase groceries or small items that they can take with them at the end of the day. The young students who work in companies have to consider the reputation of the company and the status of their corporate social responsibility strategy.

Before the day spent on site, teachers and students prepare for the experience by working through job applications, simulating job interviews, learning about the economy, taxation and more. The learning concept includes teacher training and learning materials for ten lessons. An important part of the concept is to develop collaborative skills, learn more about what it means to be a consumer and to deepen the students’ media literacy.

Alakoski and his colleague, Minna Ala-Outinen, explain that one of the advantages of Me & My City is that it is made easy for schools to participate. Schools are an institution often seen as an answer for many different kinds of developments in society and schools are contacted frequently by different kinds of organisations. Often it is not clear why the proposed project would be beneficial for the school. Me & My City does not have that problem since it has been designed to directly support the goals of the national curriculum.

There is a new Me & My City learning environment for 9th graders focused on the global economy. In this concept, 9th graders work as the board of directors of a Finnish multinational industrial company Metso. Alakoski and Ala-Outinen explain that it is interesting to see how Me & My City has an impact on different students and teachers. For one day, the teachers’ role is simply to sit and watch how the students run the city. Often those lively students, who might have certain difficulties concentrating in the classroom, perform exceptionally well in Me & My City. The teachers are often astonished by how good these students are when they are in the right kind of learning environment. As a result, it is empowering for the 12-year olds as well as the 15-year olds to visit Me & My City. They are given responsibility and begin to understand their parents’ world a little bit better. Ala-Outinen adds that Me & My City has made some teachers realise what kind of resource the parents, companies and other organisations could be for learning purposes. This way, Me & My City is bridging the gap between schools and the rest of the society (Tomi Alakoski, Minna Ala-Outinen, personal communication, May 2016).

Questions Asked in Interviews with School Principals:

-

What does the curriculum mean for your school’s strategic plan?

-

What does the curriculum mean for your day-to-day work?

-

How do your teachers react to and work with the curriculum?

-

Do your staff feel like they have an ownership stake in the curriculum?

-

What is the most innovative aspect of the curriculum?

-

What needs more work?

-

What part do you value the most?

-

Should national education priorities be set in another way?

-

Does the curriculum pull schools closer towards their purpose?

-

How did you participate in the new national curriculum process?

-

Do you feel that it is relevant for your school?

-

What do you think about the value base in the new curriculum?

-

How are you going to implement the new curriculum?

-

What is going to change with this new Curriculum?

People Interviewed for this Case Study:

-

Irmeli Halinen, Head of National Curriculum Development, Finnish National Agency of Education (now retired)

-

Arja-Sisko Holappa, Counsellor of Education, Finnish National Agency of Education

-

Johanna Honkanen-Rihu, principal, Lauttasaari School, Helsinki

-

Hanna Sarakorpi, principal, Saunalahti School

-

Sanna Schöning, principal, Laihia School

-

Janne Hirvonen, principal, Simpele School, Rautjärvi

-

Outi Ruotsala, principal and teacher, Raattama School, Kittilä

-

Education manager, Tuija Viitasaari, & director of early childhood education and basic education, Kristiina Järvelä, City of Tampere Education Department

-

Executive director Tomi Alakoski & product manager Minna Ala-Outinen, Me & My City, Economic Information Office.

Notes

-

1.

The Finnish National Agency for Education (www.oph.fi) is a national agency that is responsible for the development of early childhood education and care, pre-primary, basic, general upper secondary, vocational upper secondary and adult education in Finland. The Finnish National Agency for Education is subordinate to the Ministry of Education and Culture and its tasks and organisation are set in legislation.

-

2.

In 2016 there were 2339 schools in Finland. The figure also includes secondary schools.

-

3.

European Commission report. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/survey-schools-icteducation.

References

Aalto, M. (2016, August 6). Kouluissa on kesän aikana tehty vallankumous – mitä uudesta opetussuunnitelmasta pitäisi ymmärtää? Retrieved May 1, 2018, from https://www.hs.fi/kaupunki/art-2000002914514.html.

Finnish National Board of Education. (2016). National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish National Board of Education.

Halinen, Harmanen, & Mattila. (2015). p. 139. http://www.oph.fi/download/173262_cidree_yb_2015_halinen_harmanen_mattila.pdf.

Honkonen, S., & Lehmuskoski, J. (2015, October 30). Systeemiajattelun keinoista apua ilmiöpohjaiseen oppimiseen. Retrieved May 1, 2018, from https://www.sitra.fi/blogit/systeemiajattelun-keinoista-apua-ilmiopohjaiseen-oppimiseen/.

IFTF. (2011). http://www.iftf.org/uploads/media/SR-1382A_UPRI_future_work_skills_sm.pdf.

Luostarinen, A., & Peltomaa, I. (2016). Reseptit OPSin käyttöön (1st ed.). Jyväskylä, Finland: PS-kustannus.

Rokka, P. (2011). Peruskoulun ja perusopetuksen vuosien 1985, 1994 ja 2004 opetussuunnitelmien perusteet poliittisen opetussuunnitelman teksteinä (Doctoral dissertation, University of Tempere, 2011). Tampereen Yliopistopaino Oy, Tempere, Finland.

Simola, H. (2015). The Finnish Education Mystery: Historical and Sociological Essays on Schooling in Finland. London: Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Lähdemäki, J. (2019). Case Study: The Finnish National Curriculum 2016—A Co-created National Education Policy. In: Cook, J.W. (eds) Sustainability, Human Well-Being, and the Future of Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78580-6_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78580-6_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-78579-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-78580-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)