Abstract

This paper reflects on the need for a collaborative approach among all stakeholders and service providers at universities to promote and enhance their internationalisation efforts within higher education institutions. As outlined by the last addition to the internationalisation cycle presented by De Wit (Internationalisation of higher education in the United States of America and Europe: A historical, comparative, and conceptual analysis. Greenwood Publishers, Westport, CT, 2002), a supportive culture that will facilitate the integration of internationalisation into all aspects of institutions is critical to success. It is emphasized that internationalisation is not a goal in itself but a means to enhance the quality of education, research and service function of the university. Further, internationalisation may be enhanced by adding a collaborative component into all university services, thereby engaging key stakeholders. This paper offers a fresh and innovative approach linking formal and informal services inside higher education institutions, in order to formulate the best strategies to integrate collaborative services and approaches into the regular activities of formal or institutional services.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

Internationalisation as a concept has been extensively researched in the field of higher education as well as in other fields. In an attempt to outline the concept, many authors have agreed on a number of broad definitions to conceptualise the new, global phenomenon. The Bologna process was a key component catalysing the internationalisation efforts of European institutions. It aimed to make higher education more attractive to students from other parts of the world and to facilitate intra-European mobility (Teichler 2009); moreover, it sought to standardise system-wide European higher education processes that indirectly supported the internationalisation efforts of European higher education institutions.

The number of mobile students has grown significantly in the last twenty years, reflecting the expansion of tertiary education systems worldwide: according to the last report from Education at a Glance, nearly five million students may be included in this category (OECD 2017). European higher education institutions have also been focusing on international strategies and cooperation agreement to attract international students from all parts of the world, the ERASMUS programme being the most well-known and successful evidence of the mobility exchanges within the European Union and an important part of the internationalisation efforts of institutions. Nevertheless, mobility is not all, and a more comprehensive approach to the internationalisation of higher education is called for (Hudzik 2014), increasing awareness that internationalisation has to become more inclusive and less elitist.

One of the key parts of the internationalisation as a process is to offer internationalisation opportunities for all stakeholders within the institution. In this sense, the Bologna Process has been a great initiative to provide an accepted structure of programmes and activities that affect all parts of the institutions.

The aim of the Bologna Process (1999) was to make higher education systems more compliant and to enhance their international visibility. This unique approach aimed to establish a system that provides a convergence of higher education systems in Europe, as well as to gain visibility in other parts of the world. In fact, the Bologna Process has reached other continents and create awareness of a system that connects different higher education institutions in different regions, and therefore also their staff members and students.

Thus, this paper focuses on a key aspect of the internationalisation cycle of higher education institutions. It encourages a supportive culture that will facilitate not only mobility schemas but also the integration of internationalisation in all aspects of institutions by using a collaborative approach between formal, informal services and all stakeholders.

How Do We Define Internationalisation to Be More Inclusive and Supportive of All Stakeholders Inside the Institution?

The term began to be used widely by higher education sector in the 1980s (Knight 2012, p. 27) and over the years, the meaning of the term internationalisation has changed and, in some cases, its purpose. This has resulted in differing definitions and agreements about terminology, leaving out some misconceptions about the term. The definition of internationalisation has evolved since 1994 when internationalisation was first defined by Knight (1994, p. 3) as “the process of integrating an international dimension into the teaching, research and service functions of higher education”.

The definition of internationalisation evolved to highlight its international and intercultural dimension: “Internationalisation of higher education is the process of integrating an international/intercultural dimension into the teaching, research and service functions of the institution” (Knight and de Wit 1997, p. 8). It is important to note that Knight and de Wit identify three components in this definition: internationalisation is, first, process and second a response to globalisation (not to be confused with the globalisation process itself). Third, it includes both international and local elements, represented in the definition by the term “intercultural” (Knight and de Wit 1997).

In 2002 Söderqvist (2002, p. 42) introduced a new definition that, for the first time, described internationalisation as a change process from a national to an international higher education institution. Moreover, she added a holistic view of management at the institutional level, an inclusive approach engaging more stakeholders in the process. In fact, definitions started to move forward to a more comprehensive understanding assessed by Hudzik (2011, p. 6) as a:

[…] commitment, confirmed through action, to infuse international and comparative perspectives throughout the teaching, research, and service missions of higher education. It shapes institutional ethos and values and touches the entire higher education enterprise. It is essential that it be embraced by institutional leadership, governance, faculty, students, and all academic service and support units.

Consequently, it is claimed that a more comprehensive approach to the internationalisation of higher education (Hudzik 2014) will increase the awareness that internationalisation has to become more inclusive and less elitist by not focusing predominantly on mobility but more on the curriculum and learning outcomes (de Wit et al. 2015). One indicator of the inclusiveness and the change of focus is the recent definition of internationalisation by the Internationalisation of Higher Education study, which was requested and published by the European Parliament (de Wit et al. 2015, p. 33):

the intentional process of integrating an international, intercultural or global dimension into the purpose, functions and delivery of post-secondary education, in order to enhance the quality of education and research for all students and staff, and to make a meaningful contribution to society.

This definition is heavily informed by the commonly-used definition provided by Knight (2003). However, it extends Knight’s definition to represent the inner culture of institutions and to reflect the importance of internationalisation as an ongoing, comprehensive and intentional process that gathers together all stakeholders as internationalisation agents, focusing on all students and staff rather than only the few who have the opportunity to be mobile. Indeed, more inclusive and supportive actions were taken towards a more comprehensive internationalisation process. The next part of the chapter focuses on internationalisation strategies and the internationalisation cycle of higher education institutions, where all stakeholders play a role.

Internationalisation Strategies and Support Services

University strategic management covers a series of actions and services taking place at the institution. There are different support services (formal and informal) that impact the internationalisation process. Bianchi (2013) identifies the provision of two types of services: core (which are related to teaching and learning) and peripheral (those related to the living conditions and the environment of the host country, such as security, cultural and social activities, accommodation, transportation and visa/entry requirements). Knight and de Wit (1995) highlight the relevance of extra-curricular activities and institutional services by identifying a list of special services that are needed to support a university’s internationalisation strategy: international students’ advice services, orientation programmes, social events and other facilities for foreign guests, international student associations, international houses for students and scholars, international guest organisations, and institutional facilities for foreign students and scholars (such as libraries, restaurants, medical services, sporting facilities, etc.). According to a recent doctoral study (Perez-Encinas 2017), as well as sources including the UNESCO Book titled “Student Affairs and Services in Higher Education: Global Foundations, Issues and Best Practices” (2009) by Ludeman et al., the ESNsurvey 2016 (Josek et al. 2016), and the ISANA guide (2011), among others, a list of services that universities can offer is presented. These include: admission offices, administrative services, academic support/advising, international offices, IT and system support, counselling services, careers advisory service/employability, library, language courses, buddy/mentor systems, orientation and welcome activities, healthcare and safety, accommodation offices, campus engagement, campus eating places, student organisations, disability support office, alumni service, emergency numbers, family support, community services, sports, cultural adaptation, student affairs assessment and city offerings.

The provision of the aforementioned support services can enhance and strengthen the internationalisation strategy of higher education institutions. As a first step, institutions should analyse and develop their internationalisation plans in accordance with their needs, aims and priorities. Second, they can incorporate some of the relevant activities and support services into their strategic plans (de Wit 2002; Knight and de Wit 1995). Third, they may seek to integrate the views of key stakeholders of higher education institutions in all actions and activities to promote a more inclusive and supportive educational environment. And, finally, they may re-assess the internationalisation plan in collaboration with these critical stakeholders on an intermittent basis.

Support services and diverse activities taking place in higher education institutions under the auspices of overall university strategies have been categorized by Knight and de Wit (1995) in two main groups: programme strategies and organisational strategies. The first category relates to academic activities and services that integrate the international dimension into the higher education institution. The second category refers to the development of appropriate policies and administration systems in order to maintain that international dimension (de Wit 2002; Knight and de Wit 1995). Therefore, we may observe that support services and internationalisation activities may fall under both of those categories, which are indeed of equal importance. In order to provide a holistic approach to the internationalisation of higher education, all aspects, activities, and university strategies (programme-based and organizational) must be in focus in order to reach the mission of the institution.

Trends and Issues in International Student Services

As stated previously, there are different activities and support services that universities can offer to (international) students to support the internationalisation process of universities. Internationalisation of higher education seeks to include not only foreign or mobile students but rather all types of students in higher education. In most cases, institutions offer support services specifically oriented for international or foreign students and have a designated office for that purpose. International student services (ISS) has been an evolving concept in some institutions of higher education, while it is regarded as a well-established practice in others. Although its definition might differ from country to country or among organisational types, institutions that host international students share one mutual goal: to support international students in their educational and cultural transition during their studies abroad.

Recognising the potential impact on the students’ experiences and success, as well as recruitment and retention efforts, some institutions are becoming more intentional about equipping their ISS with the necessary resources and staffing to serve the complex needs of international students and help them develop global and intercultural competencies during their stay on campus and in the community (Ward 2016). Although the structure of ISS might differ from institution to institution, and be organised in the form of centralised or decentralised services, it is tied to programmes and services provided to students in relation to their formal and informal education at postsecondary level (Osfield et al. 2016). According to the European Union’s Erasmus Impact Study (Brandenburg et al. 2014), the increase in the number of both inbound and outbound students has led to an increased awareness of the necessity of providing support services and streamlining administrative procedures. At many universities, this has, in turn, resulted in the establishment and further strengthening of support services for international students. Providing support services does not only enhance the internationalisation vision of a university but also has a potentially important role to play in terms of attracting and retaining international students (Kelo et al. 2010), as well as building momentum for the future recruitment of high-quality students.

These trends have been identified and categorised into five major groups (Ammigan and Perez-Encinas 2018): (1) increased responsibility for providing immigration services to the international community on campus; (2) the importance of developing strong support through a collaborative programming and outreach model; (3) using key strategic communication strategies to maintain contact with international students; (4) the need for assessing international student satisfaction as a way to improve support services; and (5) the preparation for managing crisis and response to emergencies.

Collaborative Services Inside Institutions

The role of international student support services is an important driver in the internationalisation efforts of a university (Perez-Encinas 2017). In fact, due to the growing numbers of mobile students, the provision of student services has become a key topic among academics and other stakeholders involved in the process of internationalising higher education. Therefore, providing support services and integration activities by and for staff members, faculty members and students will increase the internationalisation of the campuses and, moreover, enhance their attractiveness in comparison to other institutions (Perez-Encinas 2017).

Additionally, institutions seeking to attract and retain international students are adopting student services and programming to meet their expectations (ACE 2016), in order to not only create an international campus but also to offer an inclusive environment that meets the needs of international students, both academically and culturally, not to mention personally. Indeed, figuring out the best way to meet the needs of international students is not an easy process (ACE 2016), although more programmes and services are being provided to more international students because this is becoming central to the work of all student affairs professionals at the university, not just those who work in the international office (ACE 2016). Hence, a collaborative approach is encouraged for all stakeholders within higher education institutions, with the goal of working together towards supporting an international culture with international and domestic students and staff members. Student support is requested not only by international students; domestic students may well be “interculturally deficient”. Leask (2009) suggests that international educators “move away from deficit models of engagement, which position international students as interculturally deficient and home students as interculturally efficient, when both need support”.

Another important service where a collaborative approach is important relates to the integration of international and domestic students. Besides attracting and receiving international students to enrich the campus and provide an international atmosphere, the integration of international students on the campus is desired. Unfortunately, there is still much to be done to socially integrate international students and local students. Key actions to foster integration include: (1) to identify students’ needs in the institution, regardless of whether they are domestic or international students, (2) to include all stakeholders and community members to foster engagement and (3) to associate and collaborate with different services and organizations on campus for a better social integration provided by and with different agents. Social integration has been defined by (Rienties et al. 2012) as the extent to which students adapt to the social way of life at university. Some studies have addressed the integration of students in higher education. Tinto (1975, 1998) notes that students have a variety of educational experiences, competencies, skills and values, as well as family and community backgrounds before they enter into higher education. These previous personal experiences might influence how students integrate in higher education, socially and academically. Another interesting finding from Tinto (1975, 1998) is that students do not only need to focus on their studies to graduate and succeed academically, they also need to participate in the student culture that universities provide. Authors such as Wilcox et al. (2005) found that social support by family and friends (i.e. social networks of students) had a positive influence on the study success of first-year students. This data can be related to international students and to the efforts of an inclusive and comprehensive strategy for internationalisation.

Some recommendations for the strategic development of an international community include: to connect international initiatives with the institution’s existing strategic priorities; to focus on continuous data-driven approaches to decision making; and to forge flexible coalitions with key campus stakeholders. Another recommendation is to collaborate with the international student community, which involves empowering international students to participate in open forums, serve as representatives at fairs, be responsible for the organisation of events, etc.

All these endeavours may positively impact students’ social and academic experiences. The American Council on Education (2016), in their report on “Integrating International Students”, highlights four key methods to provide the best possible experience for international students: welcoming international students, adjusting services and programmes to meet their needs, facilitating interaction between international and other students, and assessing students’ experiences. Subsequently, de Wit has identified a missing component (related to a collaborative approach); this will be explored in the following section.

The Internationalisation Cycle and the Missing Component

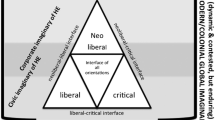

An internationalisation cycle has been developed to facilitate the phases and the process of internationalisation in higher education institutions. The modified internationalisation cycle described below by de Wit (2002) highlights that all phases of the internationalisation process in a given institution combine distinct points of view. The proposed cycle, a combination of Van der Wende and Knights’s internationalisation cycle, takes into account several variables. Van der Wende (1999) puts emphasis on the internal and external factors affecting the environment (the analysis of the context), and the implementation and long-term effects, while Knight’s cycle (Knight 1994) relates more to the awareness, commitment, planning, organisation and review. The internal circle, an addition by de Wit (2002), represents the supportive culture that will facilitate the integration of internationalisation into all aspects of institutions. There is an implicit emphasis that internationalisation is not a goal in itself, but a means to enhance the quality of education, research and service function of the university (Fig. 1).

Modified version de Wit (2002)

Internationalisation cycle.

In fact, de Wit’s (2002) modified version brings a comprehensive perspective to the internationalisation cycle by combining approaches and including the integration effect: it gathers together the six elements of Knight’s cycle (1994) with three elements from Van der Wende (1999). This means that the internal circle acts as an integration effect promoting a supportive culture in the institution. In addition, I argue that there is a missing component in the internationalisation cycle, highlighting the key inclusion of all stakeholders in the decision-making process, which undergirds the supportive culture of an institution. This is a collaborative approach. By including a collaborative approach into all services, I offer a more comprehensive and inclusive view of the internationalisation process. Internationalisation can be seen as a strategy in itself (de Wit 2009) that can be integrated into all the aspects, functions of higher education institutions, and collaborate with different networks and stakeholders. Thus, internationalization as an approach should be inherently collaborative. The distinction proposed here is to include collaborations among formal and informal services, as well as all stakeholders, to enhance the quality of education, research and service.

In Fig. 2, I offer a representation of the newly added component (on the left side) of the collaborative approach, to be taken into account along all parts of the internationalisation cycle of higher education institutions.

Conclusion

Throughout this paper, I present an evolving concept of how internationalisation is moving towards becoming more inclusive and collaborative within the internal culture at higher education institutions. The Bologna Process has been a great initiative to promote collaborative schemas and to internationalise higher education systems. Also, to create awareness for the need of an educational system that connects different higher education institutions and internationalization strategies, staff members and students in different regions. Indeed, the paper reflects on a missing component in the internationalisation cycle of higher education institutions. This is a collaborative approach that can be included as part of the internationalisation strategies to foster community engagement and more integration among students and staff members on campus.

It is important to note that internationalisation of a university is not only aimed at those mobile or foreign students but at all stakeholders playing a role in a higher education institution. In fact, it is ever more important to have an internationalisation strategy that not only focuses on programmes and actions abroad but also at home. Under the larger heading of internationalization strategy, I have identified trends in ISS in higher education institutions as falling in five major groups (Ammigan and Perez-Encinas 2018): (1) more responsibility in providing immigration services; (2) a collaborative programming and outreach model; (3) key strategic communication strategies; (4) the need for assessing international student satisfaction as a way to improve support services; and (5) the preparation for managing crisis and response to emergencies. In order to follow the aforementioned trends and actions to be taken into account, the participation and work together of all stakeholders in and outside the campus are essential. For this purpose, student affairs associations in different regions of the world serve as an umbrella for emerging issues and work to promote a social infrastructure at the higher education level.

A collaborative approach among support services at higher education institutions can enhance and strengthen the internationalisation strategy of higher education institutions by (1) identifying internationalisation needs, aims and priorities; (2) incorporating some of the activities and support services into their strategic plans; (3) integrating the view of all stakeholders of higher education institutions in all actions and activities to promote a more inclusive and supportive educational environment; (4) by assessing the internationalisation plan together with stakeholders’ perspectives intermittently. Thus, I propose that internationalization as an approach should be inherently collaborative between formal, informal services and all university constituents to enhance the quality of education, research and service function of the universities.

References

American Council on Education. (2016). Internationalizing the co-curriculum: Internationalization and student affairs. Washington, United States: American Council on Education. Retrieved from http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Pages/Internationalization-in-Action.aspx.

Ammigan, R., & Perez-Encinas, A. (2018). Encyclopedia of international higher education systems and institutions. In Trends and issues in international student services. Berlin: Springer.

Bianchi, C. (2013). Satisfiers and dissatisfiers for international students of higher education: an exploratory study in Australia. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 35(4), 396–409.

Brandenburg, U., Berghoff, S., & Taboadela, O. (2014). The impact study effects of mobility on the skills and employability of students and the internationalisation of higher education institutions. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Bologna Declaration. (1999). The Bologna process: Setting up the European higher education area.

de Wit, H. (2002). Internationalisation of higher education in the United States of America and Europe: A historical, comparative, and conceptual analysis. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishers.

de Wit, H. (2009). Internationalization of higher education in the United States of America and Europe: IAP.

de Wit, H., Hunter, F., Howard, L., & Egron-Polak, E. (2015). Internationalization of† Higher Education. Directorate-General for International Policies. Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies Culture and Education. European Union.

Hudzik, J. K. (2011). Comprehensive internationalization: From concept to action.

Hudzik, J. K. (2014). Comprehensive internationalisation: Institutional pathways to success. New York, NY: Routledge.

ISANA guide. (2011). From international education association, http://www.isana.org.au/.

Josek, M., Alonso, J., Perez-Encinas, A., Zimonjic, B., De Vocht, L., & Falisse, M. (2016). The international-friendliness of universities: Research report of the ESNsurvey 2016. Brussels, Belgium: Erasmus Student Network. Retrieved from https://esn.org/ESNsurvey.

Kelo, M., Rogers, T., & Rumbley, L. E. (2010). International student support in European higher education: Needs, solutions, and challenges. Bonn, Germany: Lemmens Medien.

Knight, J. (1994). Research monograph. Canadian Bureau for International Education.

Knight, J., & De Wit, H. (1995). Strategies for internationalisation of higher education: Historical and conceptual perspectives. In Strategies for internationalisation of higher education: A comparative study of Australia, Canada, Europe and the United States of America. Amsterdam: EAIE.

Knight, J. (2003). Updated internationalisation definition. International Higher Education, 33(6), 2–3.

Knight, J. (2012). The SAGE handbook of international higher education. London: SAGE.

Knight, J., & de Wit, H. (1997). Internationalisation of higher education in Asia pacific countries. Amsterdam, Netherlands: European Association for International Education, The EAIE.

Leask, B. (2009). Using formal and informal curricula to improve interactions between home and international students. Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(2), 205–221.

Ludeman, R. B., Osfield, K., Hidalgo, K., Oste, D., & Wang, H. (2009). Student affairs and services in higher education: Global foundations, issues and best practices. Paris, France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, UNESCO.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2017). Education at a glance 2017: OECD indicators. Paris, France: OECD Publishing.

Osfield, K., Perozzi, B., Bardill Moscaritolo, L., & Shea, R. (2016). Supporting students globally in higher education: Trends and perspectives for student affairs and services. In NASPA- Student affairs administrators in higher education.

Perez-Encinas, A. (2017). International Student exchange experience: Formal and informal support services in the host university. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Autonomous University of Madrid.

Rienties, B., Beausaert, S., Grohnert, T., Niemantsverdriet, S., & Kommers, P. (2012). Understanding academic performance of international students: The role of ethnicity, academic and social integration. Higher Education, 63(6), 685–700.

Söderqvist, M. (2002). Internationalisation and its management at higher-education institutions applying conceptual, content and discourse analysis. Helsinki, Finland: Helsinki School of Economics.

Teichler, U. (2009). Internationalisation of higher education: European experiences. Asia Pacific education review, 10(1), 93–106.

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropouts from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45, 89–125.

Tinto, V. (1998). College as communities: Taking the research on student persistence seriously. Review of Higher Education, 21(2), 167–178.

van der Wende, M. (1999). Quality assurance of internationalisation and internationalisation of quality assurance. Quality and internationalisation in higher education.

Ward, H. (2016). Internationalizing the cocurriculum: A three-part series, internationalization and student affairs. Retrieved December 16, 2016, from https://www.Acenet.edu/news-room/Pages/Internationalization-in-Action.Aspx.

Wilcox, P., Winn, S., & Fyvie-Gauld, M. (2005). It was nothing to do with the university, it was just the people: The role of social support in the first-year experience of higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 30(6), 707–722.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

<SimplePara><Emphasis Type="Bold">Open Access</Emphasis> This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.</SimplePara> <SimplePara>The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.</SimplePara>

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Perez-Encinas, A. (2018). A Collaborative Approach in the Internationalisation Cycle of Higher Education Institutions. In: Curaj, A., Deca, L., Pricopie, R. (eds) European Higher Education Area: The Impact of Past and Future Policies. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77407-7_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77407-7_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-77406-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-77407-7

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)