Abstract

Around 1970 anti-authoritarian groups rose up against industrialisation and the development of welfare. They were the vanguard of a broader societal sentiment. At the end of the 1980s environmental problems were at the core of social and political debate Despite increasing worries the pattern of consumption barely changed. Contrasting the monitor for 1970 with that of 2010, this chapter sketches the growth of material welfare and the development of quality of life. Smoking, overweight and unemployment became the new societal challenges. The domestic consumption of energy continued to grow. In this period pressure on natural capital, both domestic and foreign, increased dramatically. The Netherlands continued to be dependent on foreign lands for important material flows – in some cases to an extreme extent. 80% of Dutch grain, for example, was still imported. These developments led to shifts in the sustainable development of the Netherlands to foreign countries. The following chapters analyse the societal dynamics in the in the chains of agriculture and foods (Chap. 18), construction and building materials (Chap. 19) and energy and plastics (Chap. 20)

This chapter is written by Frank Veraart with contributions by Fred Lambert.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 The Mushroom of the New Society

How does a new society emerge from the old one? Like a mushroom on a rotting tree trunk. An alternative society emerges from the subculture of the existing order. The underground society of the rebellious youth surfaces and begins to manage itself independently of the still ruling authorities. This revolution is now occurring…

On February 5th 1970 the Amsterdam Gnome Party (Kabouterpartij) led by the former Provo activist Roel van Duijn, announced the establishment of the Orange Free State (Oranje-Vrijstaat). This had its own anthem, its own constitution and, via the Gnome Party’s city council seat, its own ‘embassy’ to the regular administration. Van Duijn and his comrades no longer wanted to remain in the opposition:

…This is the end of the underground, of protest, of demonstrating; from now on we devote our energy to building an anti-authoritarian society. We will take what we can use from the old society: knowledge, socialist ideals and the best of the liberal traditions. The mushroom of the new society feeds itself on the juices of the rotting tree trunk until it is decomposed.Footnote 1

Twelve ‘peoples departments’ were the administrative units that were to put the ideals of the new state into practice. For example, the ‘people’s department of public works’ was charged with cultivating parks and green spaces and with demolishing highways. The department of ‘environmental hygiene’ devoted itself to restoring biological equilibrium and the department ‘for need satisfaction’ aimed at building an ‘alternative economy that did not have profit as a goal, but the satisfaction of human needs.’ The Orange Free State was anti-authoritarian and pacifistic.Footnote 2

The Gnome movement was rooted in Provo, the anarchist movement that tarted public administration and authority with provocative, often one-off, demonstrations in the second half of the 1960s. Provo described itself as a ‘first, furious reaction to the emergence of a technocratic mass-culture.’Footnote 3 Provo agitated against the ‘petty folk,’ the greedy, hard-working, boring masses devoid of fantasy. The ruling elite had succeeded in suppressing the rebelliousness of workers with stimulants, drugs and amusement.Footnote 4

The proletariat has subjected itself to its political leaders and its TV. It has melted together with the old bourgeoisie into a big grey petty mass of addicted consumers.Footnote 5

Demonstrations targeted the monarchy and agitated against modern addictions like smoking, watching television and the automobile. The movement acquired international notoriety with the detonation of smoke bombs during the marriage of crown-princess Beatrix. At the end of the sixties the movement lost its momentum. Provo became just another part of ‘rebellious Amsterdam’ together with squatters and revolutionary students. This was even exploited as a tourist attraction. As part of a guided tour, and for a fee, tourists could let themselves be harangued by Provos. Authorities gave Provo a podium and took some of its criticisms to heart. This took the sting out of their actions. Provo became a victim of this ‘politics of assimilation’ and disbanded itself in 1967.Footnote 6

Parts of Provo survived in the Gnome movement. The founder, Roel van Duijn, cherished the ideal of restoring harmony between culture and nature and of searching for the ‘ideal marriage between city and countryside.’ Humans should see nature as their ally and not as an opponent that had to be conquered. With the founding of the Orange Free State, the Gnome movement wanted to give shape to societal changes and to work out prototypes of alternative ways of life. The first National Squatters day – May 5th 1970 – was a manifestation to demand a solution of the housing shortage. Gnome stores became the urban outlets for organic foods. The Gnome movement acquired a national following in more than sixty Gnome groups. Gnomes participated in the 1970 elections for municipal councils in fifteen places. Besides Amsterdam, Gnomes won seats in the city councils of Leeuwarden, The Hague, Alkmaar, Leiden, Arnhem, and Amersfoort.

But the Gnome movement was not destined for a long life. Internal conflicts took their toll and its influence declined rapidly after 1971. The movement was a typical sign of the times. Experiments and political demonstrations brought the problematic issue of well-being into the public limelight. Many other initiatives followed in the 1970s, each with its own perspective on dealing with nature, the environment and energy. In 1969, Otto Munters, a student at Leiden University, founded the ecological commune, ‘De Hobbitstee’ in the village of Wasperveen in Drenthe. Students at Wageningen Agricultural University founded the ‘Farmers’ Group’ (Boerengroep) in 1971, in which they worked together with small farmers in the search for a more equitable distribution of incomes for farmers within and without the European Community. They also mobilized protests against land reapportionments.Footnote 7 In Riethoven in the province of Brabant, the journalist Sietz Leeflang and his wife Anke founded the environmental-experimental farm ‘The Small Earth’ (De Kleine Aarde) in 1972. This project developed experiments with biodynamic agriculture and alternative energy production.Footnote 8

The environment became one of the most important societal issues. In the voter survey held prior to the national elections of 1971 and 1972, this issue headed the list of problematic issues (Table 17.1). Environmentalism was also embraced by political parties. Local initiatives and social concern acquired extra momentum with the publication of Limits to Growth, the report of the Club of Rome, that appeared in 1972 and of which half the copies printed worldwide were sold in the Netherlands.Footnote 9

Around 1970 the individual pleasures of modernisation came into conflict with collective needs. In the early 1970s, the Social and Cultural Planning Office noted the conflicts in the domain of the living environment

Recent developments, to put it in a nutshell, boil down to a scarcity of space (congestion) and increasing erosion of the quality of space as a living environment. Virtually everyone is affected by these developments: it is almost impossible to escape the smells, noise, traffic congestion, ‘horizon pollution’ and overfull vacation destinations.Footnote 10

According to the researchers, food security for the Netherlands came with a price: an enormous impact on the landscape as well as environmental degradation. The quality of nature and biodiversity declined precipitously due to developments in agriculture.Footnote 11 At the same time, increased recreation stimulated a broader appreciation of natural values and of the experience of landscapes. Land was no longer seen as solely a means of production in the food chain, but acquired new functionalities like nature and recreation. After massive bird mortality at the end of the 1960s, the pro-nature associations succeeded in bringing the negative impacts of agrarian developments into the limelight. Debates on pesticides produced the first rents in the fabric of the public-private agricultural bastion.

The environmental aspects of agricultural production also led to questions regarding food safety. Were we not busy poisoning ourselves? Consumer associations took the environmental aspects as the point of departure for a critical analysis of the food supply chain. Did we know where our food came from, what was added to it, and whether all this was healthy for us? – these were the questions. The same kinds of questions were also raised in and around the industrial zones of the Limburg mining region, the Rijnmond area and around the North Sea Canal. Did the smells, the soot pollution and the smog not compromise the health of nearby residents?

Concern about the environment and nature would wax and wane in subsequent decades. It declined in the course of the 1970s and 1980s, only to return with great force at the end of the 1980s and once again at the start of the present century. The results of the environmental movement were also variable. In some domains like sustainable energy and combating air pollution the Netherlands was quite advanced compared to other European countries. After 2000, the Netherlands fell behind in the implementation of alternative energy sources. Whence this variable performance? What were initiatives taken and by whom? What were the drivers and what were the obstacles? In this section we examine the difficult transformations in agriculture and nutrition, and the use of materials and energy between 1970 and 2015. Using the well-being monitor we first provide an overview of changes between 1970 and 2015.

2 Well-being ‘Here and Now’: Transition to a Postmodern Society, 1970 Versus 2010

Halfway through the 1970s a previously unheard of period of powerful economic growth came to an end. Labour-intensive industries, like the textile, tobacco and shoe manufactures suffered from increased foreign competition. Wages had increased substantially, so that the Netherlands was no longer a low-wage country. The growth potential of the most important key technologies, chemicals and electronics, was exhausted. This return to ‘normal’ coincided with international economic stagnation, reinforced by increasing oil prices and oil crises. The latter impacted in particular on sizeable energy-intensive industries, including chemical firms.Footnote 12 Originally the various crises had no direct effect. Exports and investments declined and fell behind international developments, but an increase in consumption nonetheless fostered economic growth. Unemployment remained low in the first few years. It was only at the end of the 1970s and well into the 1980s that the full impact was felt in the Netherlands.Footnote 13

Between 1970 and 2010 the Dutch population increased from 13 to more than 16.5 million inhabitants (Table 17.2). The consumptive expenditures of the Netherlanders increased during this period. After the mid-1980s, in addition to household appliances and a car, Dutch households possessed ever more electronic gadgets like video and cd players and computers. The economic recession at the end of the seventies slowed these developments. The 1990s witnessed a new upsurge of economic prosperity that lasted until the financial and economic crisis of 2008. Increased consumptive expenditures were reflected in continually increasing material welfare in the household (Graph 17.1).

The economic decline of the 1980s had a major impact in the area of income inequality. The decline that commenced in the late 1970s was followed by an increase after the mid-1980s. The reason was the lowering of the minimum wage and the extension of welfare benefits during the recession of the 1980s, followed by the restructuring of social security and tax reforms in the 1990s.Footnote 14 The end result was that income inequality in 2010 stood at nearly the same level as it had in 1970. The discrepancy in wages between men and women showed a more favourable development. The difference between men and women declined, but the hourly wage difference of 18% in 2010 was higher than the average for the European Union as a whole (16% in 2010).Footnote 15

In the personal sphere the differences between 1970 and 2010 show contradictory tendencies. In 2010, the average Netherlander lived longer, healthier and under ever better living conditions in comparison with 1970. Average life-expectancy and height increased. In 2010 life expectancy in the Netherlands reached 81 years. Men (78.5 years) were above the European average; women, at 82.6, just below. Increasing tobacco and alcohol consumption among women retarded increases in life-expectancy.Footnote 16 In general, alcohol use and overweight increased since the 1980s while smoking as an unhealthy habit declined (Graph 17.2).

Development of unhealthy lifestyle as a percentage of the population 1981–2011

Heavy smoking: >20 cigarettes per day

Heavy alcohol use: 1 × per week, >6 glasses alcohol in one day

Overweight: Body Mass Index (BMI) > 25 kg/m2;

Moderate overweight: BMI: 25–30 kg/m2

Serious overweight: BMI: >30 kg/m2

Source: CBS: Health, lifestyle, health care demand and supply, mortality; from 1900

This period was marked by continuing improvements in housing and utilities. Water, natural gas and electricity networks now penetrated into every corner of the country. In the 1970s and 1980s, the last slums fell prey to urban renewal projects. Investments in education manifested themselves in among other things extension of compulsory schooling and a growing number of students in vocational and academic educational programs. Netherlanders continued to be longer and better educated.

The economic decline of the 1980s and the recession after 2008 had an equivocal effect on unemployment. After 1980, unemployment quickly exceeded the ‘friction’ level of 4%. In the first half of the 1980s more than 10% of the workforce was out of work – a percentage that declined only very gradually to about 6% in the early 1990s. A period of economic growth, especially in the information and communications sector and in services, was responsible for a period of low unemployment around the turn of the century. After that unemployment rates again increased gradually (Graph 17.3). The decrease in the amount of free time per week is striking; work in particular took up an ever larger part of the day.Footnote 17 Developments between 1970 and 2010 exhibited a deterioration in the areas of employment and free time.

Other indicators of the personal life-world also show negative developments. The chance of becoming a victim of murder, for example, increased.Footnote 18 Other kinds of criminality like theft also increased. Theft accounted for about three quarters of the total number of registered crimes.Footnote 19 The total number of registered crimes grew from 2,65,000 in 1970 to 1,218,000 in 2006 (Graph 17.4).

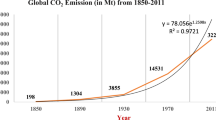

With respect to the natural environment there was an improvement in the domestic situation, but at the same time an entrenchment of the international problems. Air and water quality recovered in the course of the 1980s and thereafter.Footnote 20 The decline in biodiversity was arrested and after the 1990s there was even evidence of the beginnings of a turnaround, but in general the natural environment in the Netherlands continued to be under serious duress.Footnote 21 Per capita emissions of greenhouse gases continued to increase in this period. Measures to combat climate change did little more than stabilise emissions at 1980s levels. The consumption of fossil fuel energy and the per capita contribution to the global climate problem remained as high as ever. Dutch per capita emissions were higher than was the case in the surrounding countries of Belgium, Germany, France, Great Britain, Norway and Denmark.Footnote 22

Comparing indicators of well-being ‘here and now’ for 1970 with those of 2010 reveals a variegated picture. The problem of extreme poverty, the most important issue of well-being and sustainability in the past, became totally irrelevant to the issue of quality of life in this period. One of the last remnants, the housing shortage and in particular the elimination of slum-dwellings, was solved in this period. Instead of extreme poverty, other issues now came to the fore: like criminality, work, nature, environment and climate change. Improvements were situated mostly in the individual life-world; in the more inclusive societal and global context, indicators exhibited a deterioration or at best a stabilisation.

3 Well-being ‘Later’: Material Growth in a Cleverer and Cleaner Country, 1970 Versus 2010

The economic structure of the Netherlands changed radically after the mid-1970s. A wave of bankruptcies marked the industrial transition. Industries like shipping, textiles and many branches of manufacturing began to founder in heavy weather. The six multinationals in the economy, including Philips and AkzoNobel, relinquished some of their pre-eminence in the national economy. New key technologies like biotechnology, medical technology and information and communications technology became driving forces. Employment opportunities were increasingly found in knowledge-intensive sectors. New investments were called for in knowledge development, education, innovations and infrastructures.

Economic capital developed favourably thanks to the strong growth in investments, though at the cost of an increasing national debt. The growing stockpile of knowledge had a positive effect on economic capital. Investments in research and development acquired their own labels. At the end of the seventies investments were being channelled into ‘the information society,’ a Pollyanna that by the nineties had morphed into the ‘knowledge economy.’ Research expenditures by private firms and the government crowded close to the European average. In 2011 the Netherlands found itself in the European middle-bracket, spending a bit more than 2% of its gross domestic product on research.Footnote 23

These investments also had an impact on human capital. Expenditures for higher education increased in the 1990s in step with the European average. Between 1990 and 2010 the number of highly educated Netherlanders increased from 19% to 28% of the population.Footnote 24 Thanks to investments and new constraints on compulsory schooling, the number of students following secondary and tertiary (higher vocational and university) education increased – despite the demographic decrease. In 2010 the Netherlands boasted a better educated and (insofar as this can be deduced from life-expectancy) a healthier workforce. Insecurity about employment, however, was greater. Unemployment was higher than in 1970. More flexible work situations via employment bureaus, temporary contracts and part-time work increasingly became the norm.

Indicators for social capital exhibited no shifts. But behind the figures remarkable changes were afoot. While the social climate around 1970 was influenced by ‘left-wing, anti-authoritarian’ youth groups and environmental groups dedicated to preserving nature and the environment, by 2010 the political climate was dominated by so-called ‘right populism’ a movement that was deeply sceptical about environmental problems and climate change and that championed new issues like Dutch identity, the migrant problem and the issue of integration. We shall come back to the consequences below.

Natural capital exhibited a bifurcation. On the one hand improvements could be seen. After the 1970s, concern for the environment and the natural surroundings increased. Dutch air and water quality improved and the decrease in biodiversity was turned around. On the other hand, the incessant growth of consumption and production meant undiminished demands on energy, land-use and raw materials. Although in the 1980s there was increasing social and political concern about inter-regional, international and global environmental problems like acid rain and climate change, energy consumption in this period was still based largely on the combustion of fossil fuels. In 2010 only 4% of the energy consumption was derived from renewable sources.Footnote 25 An energy transition was still very much in the initial phases. With that, this period is characterised by an unmitigated negative development as regards the emission of greenhouse gases. The improvement in natural capital thus took place above all on the domestic front (Table 17.3 ).

4 Well-being ‘Elsewhere’: An International Trading Power, 1970 Versus 2010

Dutch support for the poorest countries continued to develop in a positive fashion. There was a substantive shift in development aid, in which the autonomy of the developing countries, but also Dutch industrial interests, acquired more leeway. Together with the Scandinavian countries, the Netherlands disbursed the most development aid per unit gross domestic product.Footnote 26

Between 1970 and 2010 economic and material growth translated into an undiminished increase in the import of raw materials. The percentage of raw materials imported from abroad increased in this period from 49% to 53%. 12,500 kilograms of raw materials were imported per capita. This flow of goods imposed an enormous burden on foreign sources of supply as well as on domestic and foreign transport facilities (Table 17.4).

5 Natural Capital and Material Flows: 1970–2010

A number of remarkable changes took place in the development of material flows between 1970 and 2010. Just as in previous periods, the flow of goods and products increased, in this case by no less than 60%. The growth was above all due to growth in biological (60%) and fossil (90%) raw materials. The most striking feature, however, was the enormous growth in the export of raw materials (230%) over against a minimal growth in import (20%) (see Table 17.5). A closer examination of the material flows can shed some light on these changes.

In absolute numbers this period experienced a substantial growth of raw materials. Per capita the growth of minerals and bio materials was modest. Solely the use of fossil resources increased with 50% (Table 17.5). This data concerns resources processed in the Dutch economy (i.e. domestic production and imports added together). In contrast data of domestic material consumption (i.e. domestic production and imports added together minus export) result in other conclusions. According to European reports the consumption of raw materials declined between 1970 and 2001 from 14.7 to 13.7 tons per capita.Footnote 27 National data show a decrease from 18 to 15.5 tons per inhabitant between 1996 and 2006.Footnote 28 These developments suggest a so-called de-materialisation of the Dutch economy. The reduction in the use of materials was above all due to a decreased consumption of mineral raw materials, the use of which declined between 2000 and 2004 from about 10 to 8 tons per inhabitant. In 2011 the Netherlands belonged to the group of European countries with a low per capita domestic consumption of materials.Footnote 29 In other words: the resource use per capita serving the economy (i.e. also serving export) tends toward stabilisation. In domestic material consumption per capita there seems a gradual de-materialisation. The situation is however more complex, the analysis of dematerialization ideally should also include complex final products (i.e. cars, machines, electronics). Possibly this dismisses dematerialisation trends, more research on this issue is necessary to come to final conclusions.Footnote 30

Another conclusion is that the Netherlands remained dependent on foreign supplies for important material flows, in some instances to a considerable degree (see Table 17.6). Almost 80% of grain consumed was still imported from foreign sources. Foreign dependency increased for mineral raw materials. Due to its geological structure, the Netherlands had long been dependent on foreign sources for ores and stone. In addition, foreign shipments of gravel – a commodity that was plentiful in the Netherlands – also increased (for the explanation see Chap. 19). Due to the closure of the coal mines, electric power plants were stoked with foreign coals. Petroleum was largely imported from overseas. It was only in natural gas that the Netherlands was a net exporter. The Netherlands was able to supply merely 47% of its material needs domestically (2008).Footnote 31

The effects of the industrial transition and the dematerialisation were visible in the material flows in two ways. A first indication was the relative decline in the processing of domestic raw materials and subsoil resources (see Table 17.7). Firms made progressively less use of domestic natural capital. This national uncoupling pertained particularly to processors of bio and fossil raw materials. These industries were fed by an increasing import of unprocessed raw materials from abroad. In the second place, total imports more than doubled in an absolute sense and exports almost tripled (see Table 17.8). Processed products formed the lion’s share. The figures sketch the rough contours of a changing industry that oriented itself less and less to domestic demand and increasingly became a link in international flows of trade and commodities.

The changes in the ten biggest flows of raw and processed products confirm this picture and reveal several core economic activities (see Tables 17.6 and 17.9). Among biological products, the material flows of raw maize fodder and mixed fodders are prominent. Both are largely for domestic consumption. These feed the strongly increased intensive livestock farming sector and its production of animal products like milk and meat. But the most striking change is the growth in the fossil raw materials and petrochemicals sector. In 2010 mineral oil and natural gas were by far the biggest material flows. The refining of mineral oil and gas also produces an enormous flow of organic chemical products like artificial rubber, plastics and other petroleum products. By contrast, the size of the flows of mineral subsoil resources decreased or grew only slightly. In 2010, in contrast to 1970, the Netherlands was no longer involved in big construction projects like the Delta Works or massive housing projects.

After 1970 the Netherlands commenced a new phase in its history and had to find an answer to new problems of well-being and sustainability. The country was confronted with the question how to combine the development of personal well-being with the collective interest in the natural environment and natural capital. It turned out to be a real struggle. We work this out in the following chapters. How could agriculture and food production achieve an equilibrium with natural values and sustainable nutritional patterns? How much room was there for the extraction of mineral resources? How should we deal with the globally shrinking sources of materials and energy? A complicating factor was the increasingly international scope of the issues, like acidification and climate change. These too demanded new answers in the subfields of biological, mineral and fossil material flows.

Notes

- 1.

Tasman, Louter Kabouter, Kroniek van een Beweging 1969–1974 (Amsterdam 1996), 401.

- 2.

Tasman, Louter Kabouter, 403.

- 3.

Roel van Duijn, Provo, de Geschiedenis van de Provotarische Beweging, 1965–1967 (Amsterdam 1985), 7.

- 4.

James C. Kennedy, Nieuw Babylon in Aanbouw, Nederland in de Jaren Zestig (Amsterdam 1995), 133.

- 5.

Roel van Duijn in Buiten de Perken, cited in Tasman, Louter Kabouter, 18–19.

- 6.

Kennedy, Nieuw Babylon in Aanbouw, Nederland in de Jaren Zestig, 136.

- 7.

D. Strijker and I.J. Terluin, ‘Rural Protest Groups in the Netherlands’ in Rural Protest Groups and Populist Political Parties, ed. D. Strijker, G. Voerman, and I.J. Terluin (Wageningen 2015).

- 8.

Leeflang was a former employee at Philips and worked as science editor for the national newspaper Algemeen Handelsblad. He was a prominent critic of nuclear energy and wrote critical articles on the petrochemical industry. Dick Hollander, ‘Tegen Beter Weten In’. de Geschiedenis van de Biologische Landbouw En Voeding in Nederland (Hurwenen 2012), 99. Egbert Tellegen and Jaap Willems, eds., Milieu-Aktie in Nederland (Amsterdam 1978), 155–59.

- 9.

Jacqueline Cramer, ‘Milieu’, Elementaire Deeltjes 16 (Amsterdam 2014), 14.

- 10.

“Sociaal Cultureel Rapport 1974” (Den Haag 1975), 83.

- 11.

There is little data on the development of biodiversity in the long term. Significant time series data is available for only a few animal and plant species. There is also data on the prevalence of flora and fauna in specific areas. The latter clearly show that the geographical range of many species is getting smaller. In 1989 a report entitled The State of Nature 2 concluded that: ‘On the average, rare species are getting rarer and common species are becoming even more common or are stable. On a regional level this is causing a decline in diversity. Overall at a national level there is an ongoing decline in biodiversity.’ cited in R.J. Bink et al., ‘Toestand van de Natuur 2’ (Wageningen 1994), p. 11; Jan Luiten van Zanden and S.W. Verstegen, Groene Geschiedenis van Nederland (Utrecht 1993), 81.

- 12.

Jan Pieter Smits, ‘Technologie, Productiviteit en Welzijn.’ in Techniek in Nederland in de Twintigste Eeuw, Techniek en Modernisering, Balans van de Twintigste Eeuw, J.W. Schot et al. eds., vol. 7, 7 vols., Techniek in Nederland in de Twintigste Eeuw (Zutphen 2003).

- 13.

Jan Luiten van Zanden and R.T. Griffith, Economische Geschiedenis van Nederland in de 20e Eeuw, (Utrecht 1989), 255. Table 10.1.

- 14.

Wiemer Salverda et al., ‘Nederlandse Ongelijkheid Sinds 1980: Loonvorming, Overheidsbeleid En Veranderde Samenstelling van Huishoudens’ in GINI Growing Inequalities´ Impacts (Amsterdam 2013); Wiemer Salverda et al., ‘Growing Inequalities and Their Impacts In The Netherlands’ in Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries´Experience, ed. Brian Nolan et al., vol. 20 (Oxford 2014), 459–87.

- 15.

Szilvia Borbély, The Netherlands: Gender Pay Gap (GPG) (Budapest 2016).

- 16.

Rutger Hoekstra and Jan Pieter Smits, ‘Monitor Duurzaam Nederland 2009.’ Monitor Duurzaam Nederland (Den Haag/Heerlen 2009), 53–55.

- 17.

Mariêlle Cloin et al., Met Het Oog op de Tijd, Een Blik op de Tijdsbesteding van Nederlanders (Den Haag 2013), 34–35.

- 18.

Paul Nieuwbeerta and Ingeborg Deerenberg, ‘Trends in Moord en Doodslag, 1911–2002.‘ Bevolkingstrends, Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek Bevolkingstrends, 1e kwartaal (2005): 56–63.

- 19.

Marcel Metze, De Staat van Nederland, Op Weg naar 2000 (Nijmegen 1996), 139–54.

- 20.

CBS, PBL, Wageningen UR (2016). ‘Vermesting in grote rivieren, 1970–2014’ (indicator 0249, version 10, 13 April 2016). www.compendiumvoordeleefomgeving.nl . CBS, Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving en Wageningen UR (2012). Milieucondities in water en natuurgebieden, 1990 – 2010 (indicator 1522, version 04, 20 September 2012). www.compendiumvoordeleefomgeving.nl.

- 21.

CBS, PBL, Wageningen UR (2015). ´Trend fauna – alle gemeten soorten – Living Planet Index Nederland, 1990–2014´ (indicator 1569, version 02 , 29 oktober 2015). www.compendiumvoordeleefomgeving.nl. PBL (2014). ´Natuur´ Website Balans van de Leefomgeving 2014. www.pbl.nl/balans2014. Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving, Den Haag.

- 22.

Data EU: Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) – CO2 time series 1990–2011 per capita for world countries (website: http://edgar.jrc.ec.europa.eu/overview.php?v=CO2ts_pc1990-2011) (consulted: 24-11-2016).

- 23.

CBS – Statistics Research & Development, 1970–1994 (via Statline), data R&D personnel en R&D investments. Walter Manshanden et al., ‘De Staat van Nederland Innovatieland, R&D: Impuls Voor Economische Groei,’ Special Issue, Strategy & Change (Den Haag 2013), 40–49.

- 24.

Data CBS Statline – Sociale Monitor; 1990–2011.

- 25.

André Meurink and Reinoud Segers, Hernieuwbare Energie in Nederland 2014 (Den Haag/Heerlen 2015), 18.

- 26.

A. Nekkers and P.A.M. Malcontent, eds., De Geschiedenis van Vijftig Jaar Nederlandse Ontwikkelingssamenwerking, 1949–1999 (Den Haag, 1999), 339–43.

- 27.

Helga Weisz, Development of Material Use in EU-15: 1970–2001, Material Composition, Cross-Country Comparison and Material Flow Indicators (Vienna 2006), 30.

- 28.

Sjoerd Schenau et al., Milieurekening 2008 (Den Haag/Heerlen 2009), 44.

- 29.

Rita Bhagethoe-Datadin and Roel Delahaye, ‘Materiaalstromen En Grondstofafhankelijkheid van de Nederlandse Economie,’ in De Nederlandse Economie 2013, ed. Hans Langenberg et al., De Nederlandse Economie (Den Haag/Heerlen 2013).

- 30.

One of the problems is the issue double counting. The Netherlands exports raw materials and processed (semi-finished) products (i.e. parts for the car industries). These partially return with the import of final products (i.e. cars).

- 31.

Sjoerd Schenau et al., Milieurekening 2008 (Den Haag/Heerlen 2009), 45–46.

Literature

Bhagethoe-Datadin, Rita, and Roel Delahaye. (2013). ‘Materiaalstromen En Grondstofafhankelijkheid van de Nederlandse Economie.’ In De Nederlandse Economie 2013, edited by Hans Langenberg, Rita Bhagethoe-Datadin, Frank Notten, and Marieke Rensman. De Nederlandse Economie. Den Haag/Heerlen: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek.

Bink, R.J., D. Bal, V.N. van den Berk, and L.J. Draaijer. (1994). ‘Toestand van de Natuur 2.’ Wageningen: Informatie- en KennisCentrum Natuur, Bos, Landschap en Fauna, Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuurbeheer en Visserij.

Borbély, Szilvia. (2016). The Netherlands: Gender Pay Gap (GPG). Budapest: WITA GPG.

Cloin, Mariêlle, Andries van den Broek, Remko van den Dool, Jos de Haan, Joep de Hart, Pepijn van Houwelingen, Annet Tiessen-Raaphorst, Nathalie Sonck, and Jan Spit. (2013). Met Het Oog Op de Tijd, Een Blik Op de Tijdsbesteding van Nederlanders. Den Haag: Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau.

Cramer, Jacqueline. (1985) ‘Milieu’. Elementaire Deeltjes 16. Amsterdam: AUP, 2014.

Duijn, Roel van. Provo, de Geschiedenis van de Provotarische Beweging, 1965–1967. Amsterdam: Meulenhoff.

Hoekstra, Rutger, and Jan Pieter Smits. (2009). ‘Monitor Duurzaam Nederland 2009.’ in Monitor Duurzaam Nederland. Den Haag/Heerlen: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek.

Hollander, Dick. (2012). ‘Tegen Beter Weten In.’ in de Geschiedenis van de Biologische Landbouw En Voeding in Nederland. Hurwenen: 4 Heuvels.

Irwin, G.A., J.J.M. Holsteyn, and J.M. de Ridder. (2005). ‘Dutch Parlementairy Election Study 2002–2003.’ NIWI-Steinmetz Archive. Amsterdam: Foundation for Electoral Research in the Netherlands, SKON.

Kennedy, James C. (1995). Nieuw Babylon in Aanbouw, Nederland in de Jaren Zestig. Amsterdam: Boom, 1995.

Manshanden, Walter, Marcel de Heide, Olaf Koops, and Tom van der Horst. (2013). “De Staat van Nederland Innovatieland, R&D: Impuls Voor Economische Groei.” Special Issue. Stratagy & Change. Den Haag: The Hague Centre for Stratagic Studies en TNO.

Metze, Marcel. (1996). De Staat van Nederland, Op Weg Naar 2000. Nijmegen: SUN.

Meurink, André, and Reinoud Segers. (2015). Hernieuwbare Energie in Nederland 2014. Den Haag/Heerlen: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek.

Nekkers, J.A., and P.A.M. Malcontent, eds. (1999). De Geschiedenis van Vijftig Jaar Nederlandse Ontwikkelingssamenwerking, 1949–1999. Den Haag: SDU Uitgeverij.

Nieuwbeerta, Paul, and Ingeborg Deerenberg. (2005). ‘Trends in Moord En Doodslag, 1911–2002.’ Bevolkingstrends, Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek Bevolkingstrends, 1e kwartaal, 56–63.

Salverda, Wiemer, Loes de Graaf-Zijl, Christina Haas, Bram Lancee, and Natascha Notten. (2013). ‘Nederlandse Ongelijkheid Sinds 1980: Loonvorming, Overheidsbeleid En Veranderde Samenstelling van Huishoudens.’ in GINI Growing Inequalities’ Impacts. Amsterdam: Gini-research.

Salverda, Wiemer, Christina Haas, Marloes de Graaf-Zijl, Bram Lancee, and Natascha Notten. (2014). ‘Growing Inequalities an Their Impacts In The Netherlands.’ In Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experience, edited by Brian Nolan, Wiemer Salverda, Daniele Checchi, Ive Marx, Abigail McKnight, István György Tóth, and Herman van de Werfhorst, 20:459–87. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schenau, Sjoerd, Roel Delahaye, Bram Edens, Isabel van Geloof, Cor Graveland, Maarten van Rossum, and Kees Jan Wolswinkel. (2009). Milieurekening 2008. Den Haag/Heerlen: Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek.

Siraa, H.T., A.J. van der Valk, and W.L. Wissink. (1995). Met Het Oog Op de Omgeving, Het Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening En Milieubeheer, 1965–1995. Den Haag: SDU Uitgeverij.

Smits, Jan Pieter. (2003). ‘Technologie, Productiviteit En Welzijn.’ In Techniek in Nederland in de Twintigste Eeuw, Techniek En Modernisering, Balans van de Twintigste Eeuw, edited by J.W. Schot, A. Rip, H.W. Lintsen, and A.A. Albert de la Bruheze, Vol. 7. Techniek in Nederland in de Twintigste Eeuw. Zutphen: Walburg Pers.

Sociaal Cultureel Rapport 1974. Den Haag: Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau, 1975.

Strijker, D., and I.J. Terluin. (2015). ‘Rural Protest Groups in the Netherlands.’ In Rural Protest Groups and Populist Political Parties, edited by D. Strijker, G. Voerman, and I.J. Terluin. Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers.

Tasman, Coen. (1996). Louter Kabouter, Kroniek van Een Beweging 1969–1974. Amsterdam: Babylon-De Geus.

Tellegen, Egbert, and Jaap Willems, eds. (1978). Milieu-Aktie in Nederland. Amsterdam: De Trommel/Vereniging MilieuDefensie.

Todoseijevic, Bojan, Kees Aarts, and Harry van der Kaap. (2010). “Dutch Parliamentary Election Studies, Data Source Book, 1971–2006.” DANS Data Guide 7. The Hague: DANS.

Weisz, Helga. (2006). Development of Material Use in EU-15: 1970–2001, Material Composition, Cross-Country Comparison and Material Flow Indicators. Vienna: Eurostat/IFF-Social Ecology.

Zanden, Jan Luiten van, and R.T. Griffith. (1989). ‘Economische Geschiedenis van Nederland in de 20e Eeuw’. Aula 190. Utrecht: Het Spectrum.

Zanden, Jan Luiten van, and S.W. Verstegen. (1993). Groene Geschiedenis van Nederland. Utrecht: Het Spectrum.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Veraart, F. (2018). The Point of Departure Around 1970: Overabundance and Discontent. In: Well-being, Sustainability and Social Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76696-6_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76696-6_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-76695-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-76696-6

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)