Abstract

The extent of economic analysis and evidence on which competition authorities and courts rely, in assessing whether specific conducts violate competition law, depends crucially on the legal standard adopted. In this article we examine the factors that influence the choice of legal standards, and hence determine the extent of economic analysis and evidence applied in competition law enforcement, focusing on the recent economic literature. We suggest a number of explanations on why the decisions of competition authorities in relation to the utilization of economic evidence may diverge from the social welfare-maximising decisions, stressing the role of substantive (or liability) standards adopted. Differences in substantive standards may be used to explain the significant divergence in the type of legal standards adopted in the EU and the USA. We also propose a practical methodology that can be used by competition authorities for identifying which legal standards minimise decision errors in the assessment of specific conduct.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The extent to which economic analysis and evidence is relied upon by competition authorities (CAs) and courts, in assessing whether specific conducts violate competition law (CL), depends crucially on the adopted legal standards, i.e. on the decision rules that provide the basis for assessment of the conducts. Broadly speaking, there are two types of decision rules that can be used: those that are effects-based and those that are object-based (to use the terminology common in the EU), which in US are referred to as rule of reason and per se rules, respectively, though the terms are not, strictly speaking, exactly equivalent.Footnote 1

Of course, a question that immediately emerges when considering the choice of legal standards, is related to the substantive (or liability) standard of the CA—the criterion on the basis of which the CA will make its decision about whether or not specific conduct violates the law.Footnote 2 In academic literature, to a large extent, the alternative substantive standards discussed are welfarist—that is, the debate relates to whether a consumer surplus or a total welfare substantive standard should be used.Footnote 3 However, in practice, a number of non-welfarist standards are common. In Europe, for example, it is often the case that the CA objective is just to “protect the economic freedom of market participants”—which would imply that any conduct that puts one or more competitors at a disadvantage would be considered unlawful, regardless of whether or not there are strong a priori grounds for making a judgement that such conduct has ultimately negative consequences/effects on consumer or total welfare. More generally, there has always been and there is still a lively debate revolving about the issue of public interest objectives especially—but not exclusively—related to the jurisdictions in BRICS and other developing countries.Footnote 4

The substantive standard adopted by a CA (or Court) will also have a significant influence on the extent to which economic analysis and evidence is relied upon by CAs in assessing whether there is liability when an effects-based legal standard is adopted. Under a welfarist substantive standard, the adoption of an effects-based legal standard will require the utilisation of a significantly greater amount of economic analysis and evidence than an effects-based legal standard would require if the substantive standard is not welfaristFootnote 5 (for details see below). This is illustrated by the exchange between WilsFootnote 6 and Rey & VenitFootnote 7 concerning the low legal standard adopted by the EU Court in the now famous Intel decision; the former commends this decision while the latter criticise it. Wils commends the decision for focusing on the effect of the conduct on “the preservation of undistorted competition”.Footnote 8 The meaning of “preserving undistorted competition” was actually made clear by the Court which, upholding the Commission’s decision in its entirety, argued that making it more difficult for a rival to compete “in itself suffices for a finding of infringement”. As we shall show below, such positions can be used in order to justify the use of a more object-based assessment for retroactive discounting by a dominant firm—which is exactly what Rey and VenitFootnote 9 consider to be the legal standard de facto adopted by the Commission and the Court.

Given these introductory remarks, we can now provide the following definitions of the two broad categories of legal standards.Footnote 10 These definitions aim to also clarify their relations to the concept of substantive standards.

Per se Legal Standard

Decisions about whether or not there is liability in the case of a specific conduct, undertaken by a firm or group of firms, are reached on the basis of a presumption about the general class (or a subclass) of conducts, within which the specific conduct falls,Footnote 11 without pursuing any investigation concerning the effects of the specific conduct, based on whatever criterion for liabilityFootnote 12 has been adopted by the CA—based on which criterion the “effects” are established.Footnote 13

Effects-Based Standards

Decisions about whether or not there is liability in the case of a specific action, undertaken by a firm, are reached after pursuing an investigation into the effects of the specific conduct, on whatever criterion for liability is adopted by the CA—on which criterion the “effects” are established. Based on what we know about the potential effects of the general class of conducts to which the conduct under investigation belongs, we do not consider that valid inferences (satisfying a sufficiently high standard of proof) can be made for the effects of the specific conduct.

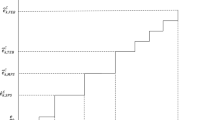

Obviously, in practice there are variations in the legal standards adopted and it is probably best to think of legal standards as forming a continuum, the extremes of which are the (strict) per se (or object-based) and the (“full”) rule of reason (or full effects-based) standards (these variants are discussed in more detail below).Footnote 14 Alternatively, an effects-based standard can be thought of as a series of per se standards, each one of which is applied to a successively more restricted class of conductsFootnote 15: in this sense, a strict per se standard, in order to establish liability or not, relies on a presumption about the most general class of conducts of the type considered, without any investigation concerning the specific conduct or more restricted subclasses to which the specific conduct belongs. Successive per se rules can be applied, relying on presumptions with respect to successively more restricted subclasses of conducts, with specific characteristics. A full effects-based standard can be thought of as a per se standard that relies on the presumption, on the specific conduct, established by a full investigation, taking into account the exact nature of the conduct and the specific market characteristics of the case under investigation.Footnote 16

Given the remarks above, we can consider of the difference between these two broad types of standards as follows. While for certain conducts a sufficiently high standard of proof can be achieved by applying a strict per se standard to the widest class of conducts to which the specific conduct belongs, under a wide range of market conditions,Footnote 17 for many other conducts this will not be the case. For these other conducts, the presumption of illegality that can be applied to the general class of conducts of this type is not very strong, therefore one needs to rely on presumptions that can be applied to subclasses of conducts and market conditions, to which the specific conduct belongs, with a more restricted set of characteristics, similar to the one under investigation,Footnote 18 in order to reach a sufficiently high standard of proof, as needed for the authority to reach the threshold for discharging its burden of proof and establishing its ultimate contention. A full effects-based legal standard must be applied in such cases, in order for the authority to reach the threshold for discharging its burden of proof and establishing its ultimate contention; a full investigation of the effects of the specific conduct must be carried out undertaken—no sufficiently strong presumption can be established by just considering the effects of a wider class of conduct similar to the specific one under investigation. While this implies that the extent and sophistication of the economic analysis and evidence utilised under a full effects-based standard is greater than under object-based rules, the extent to which economic analysis must be applied will depend on the exact variant of per se/object-based or effects-based rule that is being used.

In the literature we find references to: modified per se (or modified object-based) standards, where the application of the object rules requires the conducting of a (contextual) analysis of market and firm characteristics before it can be determined whether the specific conduct belongs to a subclass of conducts for which there is a strong presumption of illegality; structured rule of reason Footnote 19 where the conduct is assessed through a specific series of screens, to distinguish lawful from unlawful cases; in contrast to the (unstructured or) full or open rule of reason where all potentially anti-competitive and pro-competitive effects of the specific conduct are assessed and compared.Footnote 20

2 Considerations that Influence the Choice of Legal Standards and the Extent of Economic Analysis in CL Enforcement

Three sets of considerations that can influence the choice of legal standards, and hence the extent of economic analysis and evidence in CL enforcement, may be distinguished:

-

(i)

considerations that determine which legal standards are optimal, given the adopted substantive standard; literature generally examines these considerations assuming welfarist substantive standards, so below we refer to them as welfare-related considerations;

-

(ii)

hat is the substantive standard; and

-

(iii)

considerations that affect the reputation/public image of CAs.

2.1 Welfare-Related Considerations

We can categorise the first set of considerations into four distinct subsetsFootnote 21 related, respectively, to the:

-

costs of decision errors;

-

deterrence (i.e. indirect or incentive) effects of legal standards;

-

effects on predictability/legal certainty; and

-

administrative costs of enforcement.

These are the factors that have received the greatest attention in the literature. In a series of papers, Katsoulacos and Ulph (2009, 2011, 2015 and 2016a, b) used a maximization-of-welfare framework, extending the traditional error-cost-minimization approach, in an attempt to provide answers to how the considerations above affect the choice of the (optimal) legal standard.Footnote 22

According to the decision theoretic approach, the legal standard should minimise the cost of decision errors (of Type I and Type II). A formal analysis of decision errors under alternative legal standardsFootnote 23 suggests that this involves a comparison of the quality of the models/analysis available to the CA, when undertaking an effects-based investigation of a specific conduct type, in terms of the ability of the models to discriminate harmful from benign conducts, with the strength of the presumption of legality/illegality of that conduct type.Footnote 24 Katsoulacos and UlphFootnote 25 derive an explicit test for deciding whether the effects-based investigation will reduce decision errors: as expected, the discriminatory quality of the investigation must exceed the strength of presumption of illegality (or legality) of the conduct under investigation.

It is clear from this condition that it is certainly not generally true that under effects-based legal standards the welfare costs of decision errors will be lower than under per se legal standards. However, this is likely to be true in a large number of cases. Specifically, there will be an improvement in the overall welfare effect, through the lowering the costs of decision errors of enforcement, whenever a type of conduct potentially violating the law cannot be a priori considered as overwhelmingly harmfulFootnote 26 or overwhelmingly benignFootnote 27 to the welfare of those affected (so the presumption of illegality or legality is not very high) and assessment on the basis of economic evidence and economic modelling, related to the specific case, can discriminate between benign and harmful conducts with reasonable accuracy.

Most economists would argue that advances in theoretical, empirical and experimental economics in the last 25 years:

-

point quite strongly towards considering as less presumptively illegal many forms of conduct that in the past were considered as strongly presumptively illegal, including a wide class of potentially exclusionary conducts (related to bundling, rebates and exclusive contracts) and vertical restraints;

-

allow us to discriminate more accurately between harmful and benign conducts.

Both of these developments suggest that in the case of many conducts that were considered object-restrictions in the past, a move towards adopting effects-based standards would reduce decision errors, and is therefore justified.

Decision errors affect only the welfare consequences of legal standards for the cases that come to the attention of the CAs and are investigated. However, the choice of legal standards could also affect firms whose actions do not come to the attention of CAs, for example by influencing the decision of a firm to engage in potentially efficiency enhancing or anticompetitive conduct. The effects of deterrence (or incentives) on the behaviour of firms, when deciding whether or not to adopt a particular conduct, have been recognised for a long time, as probably the most important factor in legal rulemaking.Footnote 28 As Katsoulacos and UlphFootnote 29 demonstrate, effects-based rules generate, relative to per se standards:

-

absolute deterrence effects, which are too weak (too strong) when the conduct is presumptively illegal (legal), thus lowering welfare. For example, for the case of presumptively illegal conducts, all these conducts will be deemed illegal under a per se illegality rule, but some conducts will not be deemed illegal (even though they are genuinely harmful) and will be allowed under effects-based standards. This implies that absolute deterrence will be stronger under per se rules.

-

differential deterrence effects, whereby harmful actions are more heavily deterred than benign actions, thus increasing welfare. This will be so for as long as with effects-based standards the likelihood of condemning harmful conducts is greater than the likelihood of condemning benign conducts.

When a conduct is not very strongly presumptively illegal (or legal), this is sufficient for the differential deterrence effects to dominate, implying that then, in terms of deterrence effects, effects-based standards are superior. This reinforces the argument for using such rules for lowering costs of decision errors.Footnote 30

Finally, the argument that economics or effects-based standards are inferior because they generate legal uncertainty (LU)Footnote 31 does not seem to stand-up well to analytical scrutiny for several reasons. Katsoulacos and UlphFootnote 32 show that there is no monotonic link between LU and welfare. Effects-based standards do not necessarily imply legal uncertainty,Footnote 33 per se standards do not always guarantee legal certaintyFootnote 34 and, especially when the CA can adjust its penalty policy under alternative information structures, the superior deterrence effects of effects-based standards will make them the optimal choice even if they involve LU, while per se standards do not. When effects-based do generate LU they may still be superior to per se because of the superior deterrence effects that the uncertainty generates. Indeed, under some circumstances having some degree of LU (partial legal uncertainty) may be welfare-superior to having no LU.

Concerning administrative costs, it is clear that increasing the standard towards more effects-based rules will involve higher administrative costs.Footnote 35 Therefore, adopting higher standards needs to be justified by quite strong potential benefits, to compensate for the higher administrative costs.

As noted above, it is likely that for a range of conducts, now understood not to be strongly presumptively illegal (or legal), moving to effects-based standards would improve welfare due to a reduction in the costs of decision errors and an improvement in deterrence effects. Furthermore, we noted that the (potentially negative) implications of legal certainty may have been exaggerated. These factors suggest that the welfare gains from adopting effects-based standards could well compensate their higher administrative costs and that, therefore, adopting effects-based standards can be justified for conducts that were previously treated by per se rules.

2.2 The Role of the Substantive Standard (SS)

Where do the considerations examined above and the conclusions reached leave us? Although the above considerations suggest, assuming a welfarist substantive standard, that adopting effects-based standards would be justified, on the grounds of improving welfare, for many conducts that have traditionally been treated as object restrictions, the standards actually adopted remain close to per se and the extent of economic analysis applied by the vast majority of CAs today remains very low.Footnote 36 This implies that the arguments concerning decision errors, deterrence effects, legal uncertainty and administrative costs, may not be the only, or even the most important, influences in choosing legal standards and the extent of economic analysis in CL enforcement. In practice, other factors may be very important. One is the substantive standard of the authority or the court.Footnote 37

As noted in some detail in the Introduction, the SS adopted may not be that of consumer or total welfare, and this of course influences the extent of economic analysis and evidence in the assessment of potentially anticompetitive conducts. As explained, even if effects-based legal standards are adopted, the extent of economic analysis used, when the substantive standard is not welfarist,Footnote 38 would be limited or very limited. To clarify this further we need to take the following into account.

Non-welfarist SS, or non-welfarist liability criteria, can differ from welfarist SS in two ways:

-

(a)

A non-welfarist SS can be one of a continuum of criteria that need to be examined in order to form a judgement about the ultimate welfare criterion. Hence, for example, the criterion of “preservation of competition” or whether the type of conducts/market conditions under consideration have an “exclusionary effects”, becomes part of the process of reaching a judgement based on the welfare criterion. However, in the case of the latter, it is necessary to additionally examine whether the conducts could have substantial efficiency effects that in many cases might outweigh the potential exclusionary effects and thus increase consumer surplus and efficiency. We believe that the main difference in the liability standard applied in the EU and the US in recent years is of this type.

-

(b)

A non-welfarist SS may be one related to “public interest concerns”, which, as mentioned above, have been popular (perhaps increasingly so) in BRICS and developing countries. For example, the SS may focus on non-welfarist criteria such as inequality, employment or international competitiveness. These are not criteria that need to be examined when forming a judgement about the welfare criterion, i.e. they are distinct from the latter. CAs using these non-welfarist liability criteria can adopt per se or effects-based legal standards, in the sense we defined above,Footnote 39 in order to reach a decision concerning how the examined conducts/market conditions affect the selected criterion. When a CA emphasises a non-welfarist SS of this type then, of course, the extent to which it will rely on competition-related economic analysis and evidence will be very limited.

Focusing below on the case of a type-A non-welfarist SS (N-WSS), this is expected to lead to a limited application of economic analysis and evidence, for two reasons: first, as already mentioned, even if effects-based legal standards are used, under a N-WSS the extent of economic analysis will be limited, compared to the case where a welfarist SS (WSS) is used; second, with a N-WSS the likelihood of the CA adopting a per se standardFootnote 40 is higher than when the SS is welfarist. Below we explain why these statements are true. We assume that the N-WSS is that of “preserving competition” or whether the specific conduct “is likely to have exclusionary effectsFootnote 41”.

To start with, provided allegations that a specific conduct violates the law, we need to start by specifying the general population of conducts to which the specific conduct belongs and, in many cases, the market conditions that are relevant for this type of conducts, according to competition law and precedentsFootnote 42—e.g. the conditions under which dominance exists. Given this population of conducts/market conditionsFootnote 43 we can consider and compare the following alternatives:

-

A.1: WSS—per se: in this case the CA makes inferences, for example, about the effect of the specific conduct on consumer surplus (CS),Footnote 44 from the presumed effect of the population of conducts/market conditions on CS.

-

A.2: N-WSS—per se: in this case the CA makes inferences about the exclusionary effect of the specific conduct from the presumed exclusionary effect of the population of conducts/market conditions.

-

A.3: WSS—truncated effects-based (WSS TEB ): in this case the CA establishes whether the specific conduct has exclusionary effects and makes inferences about the effect of the specific conduct on CS, from the presumed effect on CS of the population of conducts/market conditions that have exclusionary effects.

-

A.4: N-WSS—effects-based (N-WSS EB): in this case the CA decides on the basis of whether the specific conduct has an exclusionary effect or not, following an investigation into it.

-

A.5: WSS—Effects-Based (WSS EB ): in this case the CA decides on the basis of whether the specific conduct has a negative effect on CS or not, following an investigation into it.

From the descriptions above, we first note that if the CA adopts a N-WSS, even if it chooses an effects-based standard (i.e. the above-mentioned alternative N-WSSEB) the extent of the economics applied would be limited relative to using an effects-based standard under a WSS (i.e. alternative WSSEB). Since, with WSSEB, additional economic analysis will have to be applied, on top of that applied under N-WSSEB, in order to show that the specific conduct does not just have an exclusionary effect, but also reduces CS.

Second, we note that since for the general population of conducts/market conditions the probability of a negative presumed effect on exclusion is higher than that of a negative presumed effect on CS (because the former is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the latter), we can say that the presumption of illegality is higher under the alternative A.2 (N-WSS—per se) than under the alternative A.1 (WSS—per se), so ceteris paribus, per se is more likely to be favoured under N-WSS. However, we need to examine this in more detail.

Note that under a WSS the CA may prefer WSSTEB to per se (alternative A.3 to A.1), because under the former the presumption of illegality is much greater (presumption of negative effect on CS is stronger for conducts that have exclusionary effects than for all conducts), given the quality (in terms of decision errors) of economic thinking and of models for establishing exclusionary effects under WSSTEB. Let us assume that this is the case.

However, under a N-WSS the CA may well prefer per se to N-WSSEB (i.e. alternative A.2–A.4) because under a per se legal standard the presumption of illegality is stronger with a N-WSS (than under WSS—per se), and the discriminatory quality of economic thinking and models for establishing exclusionary effects is the same under N-WSSEB (alternative A.4) as under WSSTEB (alternative A.3), as indicated above. Thus, under N-WSS the CA is more likely to choose per se than under WSS. Of course, this would tend to limit the extent of economic and evidence applied in enforcement when the CA uses N-WSS. Indeed, if under a WSS the CA were to prefer to adopt a WSSEB to a WSSTEB (as Rey and Venit (2015), believed should have been the case in the Intel case) then the reduction of the economics applied under a N-WSS (as that adopted in that case by the EU Court and the Commission DG COMP Legal Service) could be substantial.

2.3 The Effect of Reputation on the Choice of Standards

Competition authorities are government or independent organisations that typically have a certain degree of freedom to choose among different possible courses of action. While they are concerned with the welfare benefits that their activities bring to society, they are concerned with how their activities affect their public image and reputation. This is consistent with the widely recognised fact that, in many cases, CAs operate under performance criteria that are not always related to the welfare effects of their enforcement activities.Footnote 45

Recent work, by Katsoulacos (2017) and by Katsoulacos et al. (2016a, b) influenced by the work of Harrington (2011) and Schinkel et al. (2015), assumes that CAs maximise a utility function that depends both on a composite indicator of enforcement success and the welfare impact of the CA’s decisions, given the legal standards on the basis of which these decisions are made. The enforcement success (and thus the utility) of a CA is affected negatively by the decrease in the number of cases that the CA opens and concludes (independently of whether the decisions concern infringements) and by the increase in the number of reversals of its infringement decisions by the courts of appeal. The CA’s utility is affected positively by an increase in the welfare impact of its choices related to legal standards. A reputation-maximising CA, which does not take into account the welfare effect of its choice of legal standards, will not have incentive to adopt effects-based standards, which utilise more economic analysis and evidence, when this can lead to an increase in the likelihood that appealed infringement decisions will be annulled by the courts of appeal. On the other hand, welfare-maximising CAs will choose standards that are more effects-based and will be prepared to apply economic analysis and evidence to a greater extent than reputation-maximising CAs.

3 A Practical Approach to Choosing Legal Standards that Minimise Decision Errors

Consider a CA (and court) that adopts a welfarist SS, which has to decide whether some conduct by a firm or group of firms violates CL. How should it choose the best legal standard to apply in assessing the conduct in order to minimise decision errors Footnote 46?

We consider the CA deciding in several stages which standard is appropriate.

Stage 1

Verification and identification of the nature, object (or form) of the conduct; the CA undertakes an investigation that allows it to characterise fully the nature of the conduct.

As a result of this investigation the CA can locate the specific conduct, within a subset/subpopulation of conducts, with similar characteristics to the conduct that is alleged to violate the law, within a general category of potential anti-competitive conducts. Further, at this stage the CA is provided with or can obtain some basic information concerning market characteristics and can identify what established economic theory and available empirical evidence and case law suggest about the specific subpopulation of conducts identified. Based on what is learned in Stage 1, the CA can determine the frequency of (genuinely) harmful conducts \( \widehat{\gamma} \), the loss in welfare (negative harm) from falsely condemning benign conduct (\( -\kern0.5em {\widehat{h}}_B \)), and the loss in welfare from not condemning harmful conduct \( {\widehat{h}}_H \), for the subpopulation of conducts to which the conduct is found to belong, i.e. it can form a prior about the fraction of harmful and benign conducts in this subpopulation and the average harm across different potential market characteristics (or environments).

Thus the CA determines the average harm from this subclass of conducts

determining whether the subclass of conducts is presumptively legal or it is presumptively illegal:

presumptively legal (PL): \( \overline{h}<0 \)

presumptively illegal (PI): \( \overline{h}>0 \)

Also it can define indicators of the strength of the presumption of legality, s PL (illegality, s PI) as followsFootnote 47:

At the end of Stage 1, the CA can reach a decision on the case without any further investigation, using a per se legality (PSL) standard (thus allowing the conduct), or a per se illegality (PSI) standard (thus disallowing the conduct). This could be appropriate if the strength of the presumption of legality or illegality are very strong, so by using per se the CA can satisfy its standard of proof for establishing its ultimate contention (there is very little risk of substantial decision errors that could justify the use of an effects-based standard that would aim to discriminate whether the conduct in question is benign or harmful). For example, if \( \widehat{\gamma} \) is close to unity then this would be sufficient to make the strength of the presumption of illegality in Eq. (3) extremely large, something that would justify the use of a per se illegality standard (for example, this is the rationale for using this standard in the case of explicit horizontal price fixing).

However, assume that the values of \( \widehat{\gamma},\kern0.5em {\widehat{h}}_H,\kern0.5em {\widehat{h}}_B \) are such that the CA does not consider that the strength of the presumption of legality or illegality is sufficiently great to justify (without further analysis) the use of a per se standard—it expects that this could result in too many decision errors. In this case it would need to decide which standard to use by comparing the cost of the decision errors of the alternatives. We can define:

Costs of Decision Errors (CDE) = Costs of False Convictions (CFC) + Costs of False Acquittals (CFA).

In the case of per se, the CDE are:

with a per se legality standard, and:

with a per se illegality standard:

The CA assessment must now move to the second stage.

Stage 2

Detailed identification of the characteristics of the market environment. At the end of Stage 2 the CA may make a decision using a modified per se standard subject to a significant market power (SMP) requirement. This is provided so that the investigation in Stage 2 will allow the CA to revise the values of γ and h. it is assumed that these (revised) values are γ, h H, h B.

The CA can re-determine the average harm and the strength of the presumption of illegality for these revised values of γ and h, and may decide whether it should use a (modified) per se rule subject to SMP (if for example the revised value of γ is very high, it would be justified in using a per se illegality rule on the basis of the strength of the presumption for the restricted subpopulation of firms with SMP). Using a (modified) per se standard subject to a SMP requirement is consistent with the practice of CAs throughout the world (including the US) prior to the mid-1990s, when dealing with a number of business practices undertaken by dominant firms (bundling, royalty rebates, exclusive contracts with distributors, etc.).

However, even in the presence of SMP the CA could well consider the presumption of illegality not high enough to justify the adoption of per se rules and may consider to use an effects-based standard to make its assessment, although this does not imply that the CA would necessarily move to full-blown rule-of-reason. This is the situation relating to the mentioned practices in the US (and some other countries, e.g. Canada and the UK) in the past two decades.

This suggests a third stage of analysis for choosing the appropriate legal standard.

Stage 3

Undertaking an effects-based assessment, which implies showing how, given the market environment, the specific conduct can generate social harm, on the basis of additional economic analysis, modelling and empirical evidence.Footnote 48 The CA can only identify market characteristics and relate them and the characteristics of the conduct to harm by using economic analysis and evidence with certain errors. Whether or not an effects-based standard should be chosen turns on the comparison of the costs of the decision errors with those of staying with per se, and this requires comparing the strength of presumption of illegality (or legality) with the discriminatory quality of an effects-based economic analysis.

Assuming that if the CA adopts an effects-based (EB-type) standard, it considers that the economic models and evidence it can use for assessing the specific type of conduct will lead to the finding of a law violation with probability β, 0 < β < 1, therefore a finding of no-violation will emerge with probability 1 − β. This compares to the CA deciding that there is violation in all cases under a per se illegality standard and deciding that there is violation in none of the cases under a per se legality standard. β is a probability that is much easier to understand and try to estimate (see below) than probabilities associated with the errors that the CA makes when it adopts an EB standard. Also it is important to introduce this probability to capture the intuition that when the conduct is presumptively illegal then the higher β is, the lower the cost will be of decision errors of the EB standard, for any given propensity of this standard to make errors,Footnote 49 while oppositely, when the conduct is presumptively legal the lower β is, the lower the cost will be of decision errors of the EB standard for any given propensity of this standard to make errors.

Finally, assuming that the CA considers that the following hold, concerning errors in its decisions (to be discussed below):

-

Conditional on finding a violation, the probability that the conduct is in fact harmful is β H, 0 ≤ β H ≤ 1, while the probability that it is truly benign is (1 − β Η).

-

Conditional on a finding of non-violation, the probability that the conduct is not harmful is β B, 0 ≤ β B ≤ 1, while the probability that the conduct is harmful is (1 − β Β).

At a minimum the discriminatory quality of an EB standard must be such that:

Although, as we will see below, this is not a necessary condition for the CDE of an EB standard to be lower than the CDE of per se standards.

The first thing to note is that the various probabilities are related by the following consistency constraint. For harmful cases:

and for non-harmful cases:

These expressions make it clear that if the CA improves its ability to identify correctly harmful conducts, it will have improved its ability to correctly identify benign conducts. They can be used to express the value of β Η(β Β), which would satisfy the consistency constraint as follows, given β and γ and β Β(β Η):

The CA can infer γ from the investigations it undertook in Stages 1 and 2, of the exact characteristics of the conduct and the characteristics of the market and firm(s) under investigation, and from all the available economic analyses and empirical evidence that is related to this type of conduct.

It can also infer β based on information from its past investigations of this type of conduct (with EB-type standards), and from information of investigations and decisions reached by other authorities worldwide; indeed, the latter is a standard practice used by CAs to examine what other authorities have done in similar cases. Note that given γ and β, the CA has to form judgment about either β Η or β Β, in order to infer the value of the other (given the consistency constraints).

From Eqs. (8) and (9), for β Η ≥ 0 and β Β ≥ 0:

Or, given β and γ, for β Η ≥ 0,

and for β Β ≥ 0,

Comparison of Costs of Decision Errors

The CDE of the EB standard is given by the following expression:

so:

Let

-

(i)

By comparing the CDE under EB and per se we come to: for conducts considered to be presumptively legal (PL):

iff:

where q EB, PL is an indicator of the discriminatory quality of the EB standard under PL (ratio of the probability of not finding to the probability of finding that there is violation of competition law when the conduct is benign);

-

(ii)

for conducts considered to be presumptively illegal (PI):

iff:

where

is an indicator of the discriminatory quality of the EB standard under PI (ratio of the probability of finding to the probability of not-finding violation when the conduct is harmful).

Results and Observations:

-

1.

The smaller γ is and the greater h H is, relative to h B, the greater the presumption of legality and less likely it is that EB can dominate per se in decision error terms, for presumptively legal conducts.

-

2.

EB is more likely to dominate per se the less (more) likely it is to lead to findings of violation, i.e. the smaller (greater) β is, for presumptively legal (illegal) conducts; in fact, for sufficiently small (large) β, EB will have lower CDE for presumptively legal (illegal) conducts, as long as β H and β B are positive (see also below).

-

3.

When the presumption of legality (illegality) is low (RHS is small) the CDE under EB can be lower than per se, so EB standards will be superior to per se under many potential standards differing in β Hand in β B. That is, EB standards that are low in false convictions or EB standards that are low in false acquittals can be superior to per se standards. However, more importantly, from Eqs. (15) and (16):

-

4.

For any given β, Increasing β H and hence limiting false convictions, is the most efficient way to ensure that EB is superior in CDE terms when the conduct is considered presumptively legal.

-

5.

For any given β, Increasing β B and hence limiting false acquittals is the most efficient way to ensure that EB is superior in CDE terms when the conduct is considered presumptively illegal.

-

6.

Presumptively legal conducts: If β is sufficiently small, as long as the CA can avoid false acquittals to some extent (β B > 0), the CDE of the EB standard will be lower than under per se standard, irrespective of how bad the EB standard is at limiting false convictions (i.e. even with β H = 0).

-

7.

Presumptively illegal conducts: If β is sufficiently large, for as long as the CA can avoid false convictions to some extent (β H > 0), the CDE of the EB standard will be lower than under per se standard irrespective of how bad the EB standard is at limiting false acquittals (i.e. even with β B = 0).

It is straightforward to produce simulations based on the above expressions, which would allow a CA to use the above formulas in practice, in order to decide which standard minimises decision errors. Here is an example.

Assuming that the CA believes that γ is likely to be around 0.6, and that h H is likely to be twice −h B (m = 2). The conduct is considered quite strongly presumptively illegal (authors addressing tying arrangements by dominant firms would consider lower values for γ—see Ahlborn et al. (2004); on the other hand, for RPM a much higher value may be appropriateFootnote 50). The strength of the CA’s presumption can be measured by s PI, which is s PI = 3.

Assume also that given the information available to the CA (as mentioned above), it is believed that β = 0.8.

From Eq. (8), for β B = 0 the value of β H is β H = 0, 5. As β B increases the value of β H increases, and β H = 0, 75 when β B = 1. From Eq. (16), we can see that EB is superior in CDE terms even for the lowest β B and β H values, β B = 0 and β H = 0, 5, so it is superior for all β B and β H values that are consistent with the “more objectively” identified values of β and γ.

If the strength of the PI is higher, e.g. γ = 0.8, and β is lower, e.g. β = 0.6, then for β B = 0 the value of β H is β H = 0, 666 and as β B increases the value of β H increases and β H = 1 when β B = 0, 5. Now with β B = 0 and β H = 0, 666, the CDE under EB are less than under per se; it is only when β B > 0, 2 and β H > 0, 8 that the CDE of EB become lower than those under per se. However, if β = 0.9 then even with β B and β H values at the lowest end of the relevant ranges, the EB standard will have lower CDE than the per se standards.

The argument here is that if the CA can obtain the information and knowledge required to identify β, γ and m, then it can use these to examine for which ranges of β B and β H values the CDE of EB standards is lower than under per se. If these are “reasonable” in the sense that even at low β B and β H values in the relevant ranges the CDE is lower under EB, then the CA has a very strong case for using EB.

4 Concluding Remarks

We have examined the factors influencing the choice of legal standards, and hence determining the extent of economic analysis and evidence applied in competition law enforcement, focusing on recent economic literature. We have emphasised the analytical and practical usefulness of viewing legal standards as a continuum between strict per se and rule-of-reason. We have suggested explanations of why the decisions of CAs in relation to the utilization of economic evidence may well diverge from social welfare-maximising decisions. We have emphasised the very significant, but still underexplored, role played by the choice of substantive standards on whether per se or effects-based legal standards are adopted, and on the extent that economic analysis is utilised. We have also proposed a practical methodology that can be used by CAs for identifying which legal standards minimise decision errors in the assessment of specific conducts.

Notes

- 1.

Sometimes, a distinction is drawn by legal scholars between rules (a term they reserve for per se) and standards (e.g. the “rule of reason”)—see for example, Blair and Sokol (2012). Below we neglect this distinction.

- 2.

The notion of substantive standard seems to be sometimes confused with that of legal standard. The two notions are clearly distinct: the substantive or liability standard is the criterion used (e.g. impact on consumer welfare) in order to decide whether or not a conduct violates the law; The legal standards refer to how decisions are reached. Per se rules (or standards, such as the one applied in hard-core cartel cases) are perfectly consistent with welfare-based substantive standards (such as consumer surplus and total welfare), The term effects-based standard can, at least in principle, be used when the substantive standard is not welfarist—as is used by Wils (2014) in discussing the legal standard adopted by the European Commission and Court on the case of Intel. This is notwithstanding the fact that most people tend to associate the use of the term effects-based legal standard with the case where the substantive standard is welfarist. Indeed it must be recognized that, neglecting objectives related to public interest concerns, it would make sense to use a “full effects-based” legal standard or “rule of reason” only if the substantive standard is welfarist. See also discussion below for the role of substantive standards in the choice of legal standards.

- 3.

In this paper we will not examine the pros and cons of using consumer welfare or total welfare/efficiency as the right substantive standard. Some CAs are already using a total welfare standard (e.g. in Canada, Australia and New Zealand), although in the EU and the US the CAs lean towards the consumer welfare standard (and in EU, as noted below, often a weaker standard is used, such as that concerning the competitive process). There is currently quite an intense debate on this issue, with some eminent economists arguing in favor of a total welfare standard, e.g. D. Carlton (2007). For a recent contributions, as well as an extensive review of the recent debate, see Katsoulacos et al. (2016a, b).

- 4.

- 5.

But has a more restricted objective such as protecting the economic freedom of market participants (see also below).

- 6.

Wils (2014).

- 7.

Rey and Venit (2015).

- 8.

Wils (2014) considers that an effects-based standard was used but the effect assessed was not (rightly, according to Wils) related to a welfarist objective.

- 9.

Ibid.

- 10.

Below we will use the American term per se and the European term effects-based to refer to these two broad categories of legal standards.

- 11.

Thus, under (strict) per se, the anticompetitive effects are inferred from the conduct itself. See also below for the case of modified per se standards.

- 12.

There will of course be an investigation for establishing the specific characteristics/type of the conduct itself beyond reasonable doubt, e.g. an investigation relating to the evidence for establishing that a collusive agreement existed between a group of firms.

- 13.

This defines the CA’s substantive standard.

- 14.

See Gavil (2008), and Italianer (2013), referring to Justice Stevens, who was probably the first to point out that one should think of legal standards (for dealing with restraints under US Section 1) as forming a continuum with per se and rule of reason being at the opposite ends of this continuum. As Italianer /2013) notes, the US Supreme Court has explicitly recognized that “the categories of analysis cannot pigeonholed into terms like ‘per se’ or …. ‘rule of reason’. No categorical line can be drawn between them. Instead, what is required is a situational analysis moving along what the Court referred to as a ‘sliding scale’”. See also below.

- 15.

This concern restricts sets of characteristics that converge to the specific characteristics of the case under investigation—in terms of the exact characteristics of the conduct and the characteristics of the specific firm(s) and market.

- 16.

Note that, while in the US a per se offence concerns conduct that is necessarily and irretrievably unlawful, this is not necessarily the case in the EU, where the object-based standard may refer to a “rebuttable per se” rule; an effects-based standard is usually thought of as falling short of the full-blown rule of reason, in terms of the extent of discretion of the authority’s case-by-case decision-making approach. See Katsoulacos and Ulph (2009). Also, Gavil (2008), ibid. p.141. We will return to some of these distinctions below. For all intents and purposes we will treat per se as equivalent to object-based and rule of reason as equivalent to effects-based. In the EU, agreements under Art. 101 are rebuttable. However, there are cases in EU competition law that are strictly prohibited as such: RPM, parallel trade restrictions, and restrictions on cross-sales in vertical contracts.

- 17.

For example, for explicit horizontal price fixing agreements. The presumption of illegality is extremely strong for this wide class of conducts and therefore it is enough to know that the conduct belongs to this class, to infer with more or less certainty that its effects will be detrimental.

- 18.

This implies that the CA will have to carry out additional investigation, compared to when a strict per se rule is used, in order to identify the exact subclass of conducts to which the specific conduct belongs.

- 19.

For example, a structured rule of reason was proposed recently in the US (Supreme Court of California, In re Cipro Cases I and II, No. S198616 (Cal. May 7, 2015) for “pay-for-delay” settlements between the patent holder and generic manufacturers. Also a structured rule for reason was proposed by the US Supreme Court in dealing with RPM (in Leegin Creative Leather Products Inc. v. PSKS Inc.), 2007. and, different types of structured rules of reason have been proposed for dealing with predatory practices—see De la Mano and Durand (2005).

- 20.

- 21.

- 22.

Extensive references and reviews of the literature related to these issues are contained in these papers. See also Padilla (2011, p. 435). Of course, in principle, issues related to decision errors, deterrence and legal uncertainty could also be considered under non-welfarist substantive standards. However, in these cases it is not clear how one would measure the “costs” of errors, over- or under-deterrence, and legal uncertainty, which in the case of welfarist substantive standards are measured in terms of harm (welfare).

- 23.

Katsoulacos and Ulph (2009).

- 24.

A measure of how far the conduct is from the borderline of being legal/illegal—Katsoulacos and Ulph (2009).

- 25.

Ibid.

- 26.

Such as explicit horizontal price fixing agreements. For this type of actions, a per se illegality standard should be (and, indeed, it is) used.

- 27.

Such as certain information exchanges between firms which by their very nature and characteristics are highly unlikely to have adverse effects and hence a per se legality standard should be used—that is, a standard according to which all such exchanges are deemed as per se legal, without examining the welfare implications of each case, using economic analysis. Note that in the EU a conduct regarded as per se legal can still be rebutted by the authority. The relevant expression for presumptively Legal conducts can be found in Katsoulacos and Ulph (2009).

- 28.

Joskow (2002) argues that deterrence effects are more important than the costs of decision errors, as they include the (cost of) responses and adaptations that targeted firms, as well as other firms and markets in general make to antitrust rules. Kai-Uwe Kuhn (Kühn 2011) stresses the importance of deterrence effects (which he terms incentive effects) in the context of the debate on optimal standards for information exchanges between firms. See in particular page 416 of his contribution to the OECD (2011) report.

- 29.

Katsoulacos and Ulph (2009).

- 30.

The importance of deterrence and procedural factors is shown in Katsoulacos (2009) where the above framework is applied to the analysis of legal standards for refusals to license intellectual property rights. Katsoulacos and Ulph (2011) also show that it is important to take into account other certain procedural features of a CA’s operations: the coverage rate (i.e. the fraction of actions investigated by the CA), delays in decision-making, and the penalty regime. These procedural factors enter explicitly into the welfare comparison of different legal standards.

- 31.

Katsoulacos and Ulph (2016) make the important distinction between uncertainty generated by decision errors, which always reduces welfare, and uncertainty because firms do not know the assessment that the CA will make were their actions to be investigated. The latter is what is usually considered to be the legal uncertainty associated with effects-based standards.

- 32.

- 33.

Katsoulacos and Ulph (2015).

- 34.

Rey and Venit (2015).

- 35.

Though it should be recognized that the increase need not be substantial especially given the advances in information technology in recent years and the enhanced ability to gather and process big data sets.

- 36.

There are exceptions to this, such as the US and Canada, but the statement does in fact reflect the reality in the vast majority of other jurisdictions.

- 37.

Generally, the CA will recognize, from case law, and adopt the substantive standard that is used by the Courts.

- 38.

Such as the preservation of undistorted competition which require that conducts do not make it more difficult for a rival to compete).

- 39.

Meaning that with per se standards we rely on making inferences about the effects of a specific conduct from what we already know about the effects of populations of similar conducts; with effects-based standards we do not rely on making such inferences and try to identify the effects by investigating the specific conduct in detail.

- 40.

With very limited use of economics.

- 41.

Here we interpret the term exclusionary effects as making it more difficult for rivals to compete.

- 42.

Strictly speaking, in the case of conducts for which a contextual analysis of market conditions is important, the per se rule is not a “strict per se” rule—the latter being based purely on a presumption about the characteristics of the conduct. “Modified per se” is a more appropriate term for the case where market conditions are taken into account and it entails the population of conducts/market conditions where a presumption of illegality has to be made. Below we will refer simply to per se rules when considering either “strict per se” or “modified per se” rules.

- 43.

Tying-related conduct would be a good example. A number of alternative legal standards have been proposed for their assessment, ranging from per se (illegality) to full effects-based; see, Ahlborn et al. (2004) who favour an intermediate legal standard (structured rule of reason).

- 44.

The alternative SS could be total welfare.

- 45.

The performance criteria used to assess the activities of CAs are extremely heterogeneous. On one side there is the experience of UK’s OFT, which is subject to positive impact assessment in order to achieve a target of 5:1 (now 10:1) ratio of benefits to consumers relative to the cost to the taxpayers. On the other side, many authorities still use crude output indicators (e.g. the number of handled cases) or indicators of enforcement success (proportion of decisions supported by the courts) instead of welfare outcome indicators as important performance criteria. At the present, there is still no adequate design for a performance evaluation (Kovacic et al. 2011).

- 46.

For the remainder of this section we will assume that the choice is made on the grounds of decision-error minimization; we will also neglect all the other considerations that influence this choice (which were examined above).

- 47.

See also Katsoulacos and Ulph (2009).

- 48.

At this point we disregard the fact that the CA may choose a truncated or a structured effects-based standard.

- 49.

And therefore, the more likely that the CDE of EB will be lower than the CDE of Per Se—see also comparison below.

- 50.

See for example Katsoulacos and Ulph (2009), Section V.

References

Ahlborn C, Evans D, Padilla J (2004) The antitrust economics of tying: a farewell to per se illegality. Antitrust Bull 49(1):287–341

Alese F (2008) Federal antitrust and EC competition law analysis. Ashgate Publishing, Farnham, p 129

Baker JB, Salop SC (2015) Antitrust, competition policy and inequality. Georgetown University Law Center, Mimeo

Blair RD, Sokol DD (2012) The rule of reason and the goals of antitrust: an economic approach. Antitrust Law J 78(2):471–504

Carlton DW (2007) Does antitrust need to be modernized? Economic analysis group, discussion paper - EAG 07-03

De la Mano M, Durand B (2005) A three-step structured rule of reason to assess predation under article 82, DG COMP DP. http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/competition/economist/pred_art82.pdf. Accessed 09 Sep 2016

Fox EM, Sullivan L (1987) Antirust-retrospective and prospective: where are we coming from? Where are we going? NYUL Rev 62:936

Gavil AI (2008) Burden of proof in U.S. antitrust law. In: Issues in competition law and policy 1 125, ABA Section of Antitrust Law

Harrington J (2011) When is an antitrust authority not aggressive enough in fighting cartels? Int J Econ Theory 7:39

Huschelrath K (2009) Competition policy analysis: an integrated approach. ZEW Econ Stud 41:241

Italianer A (2013) Competitor agreements under EU competition law. 40th annual conference on international antitrust law and policy, Fordham Competition Law Institute, New York

Joskow PL (2002) Transaction cost economics, antitrust rules, and remedies. J Law Econ Org 18(1):95–116

Katsoulacos Y (2009) Optimal legal standards for refusals to license intellectual property: a welfare-based analysis. J Compet Law Econ 5:269

Katsoulacos Y (2017) Judicial review, economic evidence and the choice of legal standards by utility maximizing competition authorities, Mimeo. http://www.cresse.info/uploadfiles/Paper%20on%20EB%20vs%20PS%20YK%20New%20Model%2023052017.pdf

Katsoulacos Y, Ulph D (2009) Optimal legal standards for competition policy. J Ind Econ 57(3):410–437

Katsoulacos Y, Ulph D (2011) Optimal enforcement structures for competition policy: implications of judicial reviews and of internal error correction mechanisms. Eur Compet J 7:71–88

Katsoulacos Y, Ulph D (2015) Legal uncertainty, competition law enforcement procedures and optimal penalties. Eur J Law Econ 41(2):255–282

Katsoulacos Y, Ulph D (2016) Regulatory decision errors, legal uncertainty and welfare: a general treatment. Int J Ind Organ 53:326–352. (Available online 24 May 2016)

Katsoulacos Y, Avdasheva S, Golovaneva S (2016a) Economic analysis and competition law enforcement: lessons for developing countries from the case of Russia. Mimeo, New York (available from authors on request)

Katsoulacos Y, Metsiou E, Ulph D (2016b) Optimal substantive standards for competition authorities. J Ind Compet Trade 16(3):273–295

Kovacic WE, Hollman HM, Grant P (2011) How does your competition agency measure up? Eur Compet J 7:25–45

Kühn K-U (2011) Designing competition policy towards information exchanges – looking beyond the possibility results. In: Information exchanges between competitors under competition law, OECD Competition Committee, 11 July 2011

O’Donohue R, Padilla AJ (2008) The law and economics of art.82 EC. Hart Publishing, New York, pp 183–184

OECD (2011) Information exchanges between competitors under competition law. OECD Competition Committee, 11 July 2011

Padilla J (2011) The elusive challenge of assessing information sharing among competitors under the competition laws. In: Information exchanges between competitors under competition law, OECD Competition Committee, 11 July 2011

Rey P, Venit JS (2015) An effects-based approach to article 102: a response to Wouter Wils. World Compet 38:3–29

Schinkel MP, Tóth L, Tuinstra J (2015) Discretionary authority and prioritizing in government agencies. Amsterdam Center for Law & Economics, working paper no 2014-06. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2533894. Accessed 9 Sep 2016

Wils W (2014) The judgment of the EU general court in Intel and the so-called more economic approach to abuse of dominance. World Compet 37:405

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful to the participants of the International Conference on Institution Building of the Competition Authorities in South East Europe for many helpful comments and suggestions. The author is also grateful, for the helpful discussions on the subject of this article, to Svetlana Avdasheva, Svetlana Golovaneva, Joe Harrington, Frederic Jenny, Eleni Metsiou and David Ulph.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

<SimplePara><Emphasis Type="Bold">Open Access</Emphasis> This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.</SimplePara> <SimplePara>The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.</SimplePara>

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Katsoulacos, Y. (2018). Considerations Determining the Extent of Economic Analysis and the Choice of Legal Standards in Competition Law Enforcement. In: Begović, B., Popović, D. (eds) Competition Authorities in South Eastern Europe. Contributions to Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76644-7_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76644-7_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-76643-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-76644-7

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)