Abstract

There is nothing simple and straightforward about competition authorities, their design and operations. Even in the most developed countries, those with a long and uninterrupted tradition of market economy and competition policy enforcement, there are dilemmas about the role, organisation, leverage, accountability, and funding of the competition authorities, among other things. There is no blueprint for the first best design of competition authorities, but rather certain guidelines and best practices—and not all of them consistent over time. It is hardly surprising that in South-East Europe the dilemmas are multiplied, as the region does not have a long tradition of market economy and competition policy enforcement; for most of the countries in the Region competition policy is a novel notion, and rule of law is not exactly a regional hallmark. Clearly, challenges for institution building of competition authorities in South-East Europe are immense.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Competition Authorities

- Competition Policy Enforcement

- Uninterrupted Tradition

- South East Europe

- Competition Advocacy

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

There is nothing simple and straightforward about competition authorities, their design and operations. Even in the most developed countries, those with a long and uninterrupted tradition of market economy and competition policy enforcement, there are dilemmas about the role, organisation, leverage, accountability, and funding of the competition authorities, among other things. There is no blueprint for the first best design of competition authorities, but rather certain guidelines and best practices—and not all of them consistent over time. It is hardly surprising that in South-East Europe the dilemmas are multiplied, as the Region does not have a long tradition of market economy and competition policy enforcement; for most of the countries in the Region competition policy is a novel notion, and rule of law is not exactly a regional hallmark. Clearly, challenges for institution building of competition authorities in South-East Europe are immense.

This edited volume addresses two challenges. The first one is institutional design of the competition authorities, which takes into account specific features of the SEE countries, especially their economic structure and the lack of resources that can be allocated to the competition policy, specifically human capital. The second one is the role of economics in the competition law enforcement—the central job of competition authorities. That role is no longer controversial in the developed jurisdictions, but the introduction of economic methods into the operation of competition authorities of SEE countries is not straightforward.

Within the institutional design domain, three crucial questions were asked. The first one was about the character of the desirable competition policy for SEE countries since that very character greatly affects the design suitable for the given competition authority.

Paolo Buccirossi and Lorenzo Ciari examined the SEE economies to describe where they stand in terms of these characteristics, and to derive policy implications on how their competition policy should be designed and implemented, affecting the desirable design of the competition authorities. It was demonstrated that the existence of high barriers to entry and poor institutional quality points to the importance of an institutional set-up where the independence and transparency of the competition authorities is maximised within the context of an administrative model. Also, no sector or enterprise, including SOEs, should be excluded from competition law enforcement, and competition law provisions should ensure that the voice of the competition authority is heard whenever new legislation that could potentially affect competition is introduced, i.e. that competition advocacy should be vigorously pursued by the authorities. In terms of competition enforcement, while the role of advocacy emerges as crucial, along with the prosecution of entry-foreclosing abuses, a more lenient approach to merger control can be suggested, in the form of high notification thresholds. In short, a robust and focused competition policy is the recommendation for institutional building the competition authorities in SEE countries.

In his contribution Boris Begović asked, within the conceptual framework of middle-income convergence trap, whether competition policy is good for the growth of SEE countries, taking into account that different levels of economic development influence different engines of economic growth. The answer was that SEE countries are in the middle-income convergence trap and that they should base their growth on innovations and the increase of total factor productivity rather than on accumulation of production factors. Since vigorous competition is a precondition for innovation and productivity growth, there are ample reasons for competition policy to be enforced. Additionally, since most of these countries have a substantial legacy of non-market economy inefficiency, competition policy should be designed so as to enable removing of these efficiencies by restructuring and easing entry and exit. That means that mergers (which are inevitable for effective restructuring) should not be strictly controlled and that competition advocacy should be used for decreasing entry and exit barriers.

The conclusion from these two papers is that the institutional design of the competition authorities in SEE should provide a strong role for competition advocacy, which would make markets more competitive and that would allow for the restructuring of these economies, by focusing on competition law infringements rather than to the merger control.

The second dilemma encountered by the authors writing about the institutional design of competition authorities is related to the functions that the competition authority should encompass—the dilemma between the single-function, i.e. specialised competition authority, and authorities with multiple functions. The most prominent dilemma of than kind in SEE countries is the inclusion of the state aid control function within the competencies of the existing competition authorities.

Dušan Popović examined the institutional design of state aid monitoring authorities in SEE countries and concluded that, regardless of the model chosen, state aid control cannot presently be performed in an entirely independent manner. The reasons for this can be found in the instability of democratic institutions and the limited expertise that exists within the state apparatus, in the area of competition law and state aid. The author compares the current situation in SEE countries with the pre-accession experience of Central and Eastern European countries, and concludes that the efficiency of state aid control will improve only when the SEE countries near the end of their European integration process. Since the SEE countries established their state aid monitoring authorities at the beginning of their (ongoing) European integration process, and enlargement is no longer the European Union’s priority, it seems highly likely that the state aid authorities in SEE countries will, for the time being, only continue with their pro forma activities.

In his contribution Andrej Plahutnik analysed the requirements for an efficient competition authority. The author concluded that efficient institutions are not dependent on the number of staff, but on the level of the qualification, good management and full independence from political and economic influence. The author finds that political influence with regard to state aid most likely cannot be avoided. Therefore, merging the competition authority with the state aid authority may lead to greater political pressure even in the area of “pure” antitrust enforcement.

Both authors conclude that, at present level of democratic and economic development, specialised competition authorities are a better option for SEE countries than the establishment of a multifunctional authority.

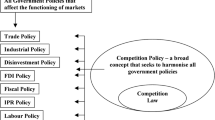

Finally, as competition policy includes both competition law enforcement and competition advocacy, the third dilemma is about allocation of the competition authority resources between the two. The previous papers demonstrated the significance and effectiveness of competition advocacy, hence the two following papers shed some light on the advocacy efforts and challenges of two specific cases: Greece and Serbia.

In his contribution Dimitris Loukas emphasises that the scope and intensity of the Greek competition authority’s advocacy agenda entailed certain risks in recent years. The first risk is related to the over–extension of scarce human resources, often to the detriment of expeditious and effective enforcement. The second risk pertains to the possibility of non-competition policy considerations creeping in to the authority’s decision making process in the area of advocacy. Such non-competition policy considerations usually stem from the Government efforts to resolve the difficult economic and financial situation that the country is dealing with.

Similarly, Ivana Rakić analysed the Serbian experience with competition advocacy. The author concluded that the authority’s advocacy activities were not fully recognised by policy makers and that it needed to gain more credibility and resources as an effective and impartial advocate for competition. The authority must therefore give continuous attention to building a competition culture, through aggressive public relations activities and dissemination of information. The evaluation of the effectiveness of competition advocacy in Serbia is hampered by the fact that there is no systematic information about implementation experience.

The conclusion is that competition advocacy is a very effective tool for competition policy, which in many cases is more efficient than competition law enforcement. This clears the way for consideration of the role of economics in competition law enforcement.

In his contribution Yannis Katsoulacos focused to the consideration of the extent of economic analysis and evidence in competition law enforcement, i.e. in the operation of competition authorities in this area. It was demonstrated that the extent crucially depends on the legal standard adopted by the competition authority and by the courts in charge of judicial revision of competition legal cases. The contribution examined the factors that influence the choice of legal standards, and hence determine the extent to which economic analysis and evidence are applied in competition law enforcement, focusing on the recent economic literature. A number of explanations were suggested as to why the decisions of competition authorities, in regard to the utilisation of economic evidence, may diverge from the social welfare-maximising decisions, stressing the role of the substantive (or liability) standards adopted. Differences in substantive standards may be used to explain the significant divergence in the type of legal standards adopted in the EU and the USA. The most important segment of this contribution, for the institution building of competition authorities in SEE, is a proposed practical methodology that can be used by authorities for identifying which legal standards minimise decision errors in the assessment of specific conduct.

Russell Pittman provided a non-economist guide to three economist’s tools for competition law enforcement, taking into account that the importance of economics in analysis and enforcement of competition policy and law has increased immensely in developed market economies in the past 40 years. Nonetheless, in most SEE countries competition law itself has a history of 20–25 years at most and economic tools that have proven useful to competition law enforcement in developed market economies, by focusing investigations and assisting decision makers in distinguishing central from secondary issues, are inevitably not as well understood. His paper presents a non-technical introduction to three economic tools that have become widespread in competition law enforcement, and especially in the analysis of proposed mergers: critical loss analysis, upward pricing pressure, and vertical arithmetic. The first is used primarily in the context of horizontal mergers for both market definition and the analysis of potential competitive effects of mergers, while the second and third are used primarily in the analysis of potential competitive effects: the second in horizontal mergers, and the third in vertical mergers. All of them are useful economic tools for competition law enforcement by competition authorities in SEE, improving the probability of success of the enforcement.

Virtually all cases of competition law enforcement related to the concentration of enterprises, restrictive agreements, and abuse of dominant position include the definition of relevant markets. Siniša Milošević et al. dealt in their contribution with different quantitative methods for defining relevant markets. It was demonstrated that the selection depends most importantly on the very nature of a specific product market and the availability of data. The paper presents the use of methods that are based on the price movement of the products under consideration: correlation, the stationarity test (unit root test), the cointegration test, and the Granger causality test, and it explores the reliability of these tests in the process of specifying the relevant market. As an example, the practical implementation of price-based tests was demonstrated on an analysis of monthly time-series data related to the price of three products during a 4-year period. The paper presented a set of economic/econometric tools that are rather simple, and therefore can be used even by less experienced competition authorities, such as those in SEE.

The last two contributions in this edited volume are focused on the merger control. In his paper Bojan Ristić developed a merger simulation model based on the application of Cournot’s theoretical competition model as a reduced form of two-stage competition in oligopoly markets, in the circumstances with limited capacities. This provides competition authorities a valuable tool for analysing the unilateral effects of horizontal mergers. The outcome of the two-stage competition, where firms chose to have a certain level of capacity, before the price competition, coincides with the outcome of the Cournot quantity competition model. The utilisation of the simulation method could be perceived as a complementary analytical tool for controlling concentrations, capable of decreasing the likelihood of common regulatory mistakes—false positive or false negative conclusions. It does not require significant additional time, data or other resources. If the relevant market was properly specified, all elements are most likely already available. The simulation method certainly allows significant influence of economic theory in merger control, which is in line with the wave of the so-called “more economic approach” in European Commission practice, by incorporating the intensity of the competition and merger efficiencies into one comprehensive economic model. Furthermore, calibration could be seen as a low-cost, and sometimes the only alternative to a full-scale merger analysis, by using econometry in equipping the selected economic model for estimating demand and cost functions. Of course, this does not exclude the possibility of using an econometric approach, when authorities have sufficient time, reliable data and resources for such an endeavour.

Finally, Radu Paun and Danusia Vamvu in their contribution used the difference-in-differences (DiD) methodology to econometrically ex-post assess the impact of a merger on the Romanian retail market in terms of price dynamics. In the merger review process, they identified five potentially problematic locations and accordingly selected suitable and representative time intervals, product categories, as well as the Treated and control groups. The implementation of the DiD technique through regression analysis rendered 55 case estimates, of which 49 match the DiD hypotheses and are thus considered reliable. In each of these cases they estimated the percentage change in the price of a product category in a certain store, due to merger clearance. The results indicate that the approved merger did not lead to general price increases: in 33 of the 49 cases the merger impact on prices is not statistically significant different from zero, and only 3 of the 49 cases show price increases. This example of the econometric ex-post analysis of merger effects proved to be useful for replicating such tests in SEE countries.

There are two main lessons to be learned from all the contributions in this volume. The first one is that SEE countries share some particular institutional and economic features that made institutional building of their competition authorities specific compared to developed jurisdictions, with a prominent role of competition advocacy and rather restricted merger control in the area of competition law enforcement. With substantial barriers to entry, there is ample ground for competition advocacy in SEE. The second lesson is that introduction of economic methods, though inevitable, should not be straightforward, but rather focused on simple solutions and the easy wins in building confidence and expertise of the competition authorities of the Region.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

<SimplePara><Emphasis Type="Bold">Open Access</Emphasis> This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.</SimplePara> <SimplePara>The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.</SimplePara>

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Begović, B., Popović, D.V. (2018). Introduction. In: Begović, B., Popović, D. (eds) Competition Authorities in South Eastern Europe. Contributions to Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76644-7_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76644-7_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-76643-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-76644-7

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)