Abstract

This chapter deals with a unique Basque invention—the gastronomic society, sometimes also referred to as the cooking society (in Spanish, sociedad gastronomica; in Basque, txoko). The author gives a brief overview of the historical origins of the txoko and its developments until the present time and discusses the formal and informal dimensions of the txoko that give life to the institution. He also notes the homogenization and differentiation processes that explain some of the cultural peculiarities of the Basque Country and its culinary geography and history. The chapter concludes with an attempt to contextualize the phenomenon of the gastronomic society, particularly in relation to the unique position that the txoko occupies as an institution between the public and the private sphere.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- gastronomic society

- sociedad gastronomica

- Basque Country

- culinary geography and history

- public and private sphere

The French statesman, thinker, and celebrated author of Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville (1835–1840/2000), thought that the art of association was crucial to any analysis of modern society. Since time immemorial, eating and drinking together and the socializing, cultural, and even educational effects surrounding such activities have been promoted and praised by its practitioners, ranging from Plato’s symposium to beer and sausage consumption in Bavarian beerhalls (the latter with detrimental political consequences, at least under the Nazis). In modern times some of these eating and drinking activities have become differentiated and have come to perform a number of functions. Some have taken on an institutionalized public form (as in restaurants); others have remained rather private in character (e.g., gatherings with friends and families at home). In this chapter I examine the history, development, and societal function of a unique Basque invention, the gastronomic society (Spanish, sociedad gastronómica; Basque, txoko, a diminutive of zoco, “corner”). It has both formal and informal aspects and combines private and public functions to great effect and to the pleasure of those who make use of it.

My investigation proceeds in three steps. I first trace the historical origins of the txoko and its development by the end of the twentieth century. I then delve into the formal and informal dimensions of the txoko that give life to the institution. I also note homogenization and differentiation processes that explain some cultural peculiarities of the Basque Country and its culinary geography and history. The chapter concludes with an attempt to contextualize the phenomenon of the gastronomic society, particularly in relation to the unique position that the txoko occupies as an institution between the public and the private spheres.Footnote 1

History of the Txoko

The origins of the gastronomic society lie in San Sebastián, a medium-sized city located on the Cantabrian coastline of a bahia (bay), only a few miles from the Spanish-French border (see Fig. 5.1). Thanks to this prime location, the city had developed into the administrative center of the Basque province of Gipuzkoa and had become its capital. San Sebastián’s geographical advantage and the ensuing improved communications (trains, electricity, the telegraph, and eventually the telephone had all arrived in a short period) attracted an influx of visitors during the nineteenth century and soon gave rise to early signs of a flourishing tourist industry. This process coincided with a change in the composition of San Sebastián’s working population. Rural migration from the countryside into town continued throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century, and by the late nineteenth century the migrants had already become an integral part of the city’s working population. The specific history I describe—the rise of the popular societies and especially the development of the gastronomic society—must be understood as the result of an accelerated process in which both the “plebeian” element of its working population and the portents of the tourist trade helped turn San Sebastián into a modern city with a cosmopolitan character (Aguirre Franco, 1983; Luengo, 1999).

Toward the mid-nineteenth century the city’s administration had already recorded the existence of a few dozen establishments in which sociability featured prominently. Some were cafés that tended to appeal to an upper-class clientele, offering billiards and facilities for tertulias (gatherings of a small group of like-minded people discussing culture as encountered in literature, the performing arts, or the press). However, most of these businesses were tabernas (taverns) and cidrerias (Basque, sagardotegis, “cider houses”), places where one could have a drink, customarily cider, with friends (Luengo, 1999, p. 45). This situation did not last. Increasingly, the café came to replace the tavern, notably in the city center. The cafés lost their elite and aristocratic character, and the urban space that used to be exclusively owned by a few became subject to “massification” (p. 47). The first popular society, La Fraternal, was founded in 1843, and its creation arguably symbolized that change. Its chief purpose was to bring its members together for the sole purpose of comer y cantar, “to eat and sing.” Soon, there were other societies, too, mainly of artisan background.

San Sebastián’s foremost chronicler, Felix Luengo (1999), recalled the social change that had occurred and that soon became evident culturally as well. That shift lay in the artisan sector, which had become an important sector of San Sebastián’s working population and which would emerge before long as the main protagonist in the organization of popular activities and events such as the drum parade, the tamborrada (p. 50). In the nineteenth century San Sebastián’s class and occupational divisions were manifested in spatially vertical and horizontal segregation, with the aristocratic elite occupying the city center’s high-rises and parts of the old town, and the rich seasonal visitors and tourists owning the beach chalets along the curve of the bahia (pp. 57−86). The not-so-well-off segments of the population lived in much smaller buildings in the surroundings and further from the center.

By the 1920s changing class structure had led to a new arrangement of urban space. Artisans and fishermen, who constituted the meanwhile plebeian majority of the working population, had moved into the old town, close to the harbor.Footnote 2 With a significant tourist industry having sprouted in San Sebastián in the latter half of the nineteenth century, the city’s development subsequently went beyond a few rich chalets. It increasingly encompassed the construction of tourist infrastructure, including casinos like the Gran Casino Kursaal (completed in 1887). San Sebastián witnessed a true boom in cafés and major hotels. Hotel de Londres, Hotel de Francia, and Hotel Continental all came on line in the 1880s, and more than a dozen new cafés opened their doors. The burgeoning tourist industry, together with the change in San Sebastián’s class structure, compelled a cultural change, too. San Sebastián’s leading festival and spectacular event was soon introduced: the Semana Grande (literally, the big week), which later also boasted a professionally organized tamborrada. The institutionalization of the Semana Grande was quickly followed by the construction of a new plaza de torros, “bull-fighting arena,” in Atocha (1876).

Both the tourist industry and the changing plebeian class structure eventuated in further differentiation of popular space. By 1868 the city council recorded the existence of 58 popular establishments, and the number grew to 106 in 1882 (Luengo, 1999, p. 74). The majority of these establishments, the aforementioned tabernas and cidrerias, were located in the old part of town, which by then was firmly in the hands of artisans and fishermen. One of the problems with the taverns and cider places, though, was their early statutory closing hours: no later than 10:30 p.m. A temporary solution consisted of turning taverns and cider houses into cafés, which were allowed to stay open until 1 a.m. A better, long-term solution was to have one’s own new mixed-purpose establishment that combined aspects of the tavern, the café, and eating places. For this purpose one had to invent a separate organizational form, the sociedad popular, or “popular society.” An early forerunner was the previously mentioned La Fraternal. Others rapidly opened thereafter. In the last three decades of the nineteenth century, a number of newly founded societies opened: Pescadores de San Sebastián (1869), Union Artesana (1870), La Armonia (1872), Neptuno (1878), Primero de Abril (1879), Union Obrera (1880), La Humanitaria (1892), and Euskalduna (1893). Membership ranged from 50 to 80 people, but the recruitment had a clear social profile in that all popular society members came from the environment of artisans and fishermen, and all the new establishments were intended to have inclusive democratic membership.Footnote 3

The new societies provided an infrastructure where people could drink, eat, sing, rehearse, and prepare cultural events, including plays, parades, and festivities such as the tamborrada. Some of the older societies also have had a small library or other facilities in which to read.Footnote 4 Another social function of the societies was to integrate migrants not only from the rural environment of San Sebastián but also from other parts of Spain. Later came the founding of entire societies whose names hinted at the regional origin of their members.

In the early twentieth century new political movements and parties arrived on the scene and changed the political landscape of the Basque Country. Both the social and the national question became more important and found expression in their own public infrastructure. In San Sebastián, socialists, nationalists, anarchists, republicans, but also various unions and social Catholic groups all established their own societies. As Luengo (1999) has explained, the growing industrialization, commercialization, and tourist infrastructure brought with it an increasing “democratization of recreation” (p. 102). Sports of all kinds reflected such democratization. Football, mountaineering, cars and car racing, pelota (the Basque ball game), and Atlantic rowing regattas were no longer restricted to an elite; they were henceforth open to the masses.

The activities described above led to a further democratization and popularization of the sociedades, including the participation of immigrants from other parts of Spain, and women. Most of the newly founded societies responded to the altered constituencies and the needs and demands of the increasing spectrum of the new leisure activities. The new wave of societies included prominent names that still exist: Union Artesana, Canyoyetan (1900), La Plata, Gaztelupe (1916), Umore-Ona (1906), Soka-Mutura, Euskal Billera (1901), Amaikak-bat (1907), Sporti Clai, and Ollagorra (1906). Whereas membership in the older societies had been dominated by artisans and fishermen, the societies that developed in the first two decades of the new century symbolized the rise of the new middle class in San Sebastián. These new societies were subject to increased regulation and had to communicate and collaborate with the city’s administration. On the whole these changes made perfect sense, largely because the Semana Grande, including the tamborrada, had developed into full-time activities and demanded long-term planning, official sponsoring, and maximum participation.

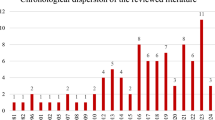

Between 1925 and 1936 San Sebastián witnessed a further major boom, the founding of 55 new societies dealing with a wide range of activities in the realms of music, sports, religious activities, and culture. But the most interesting aspect of the differentiation process was the development of gastronomic, or so-called cooking, societies—organizations whose primary purpose was to cook and consume food. To be sure, a few societies devoted solely to cooking had already been founded at the beginning of the twentieth century, most prominently Cañoyetan (1900) and Euskal Billera (1901). They were joined by societies that were initially more interested in sports but that then turned into cooking societies: Gimnastica de Ulia (1917), Sociedad de Caza y Pesca (1919), and Ur-Kirolak (1922). In the 1920s new cooking societies developed that had their origins first in republican and nationalist circles: Aizepe (1921), Gure Txokoa (1925), Sociedad Illumpe and Donosti Berri (both 1927), and C. D. Vasconia and Zubi Gain (both 1928). The advent of the republic was greeted by another wave of new establishments: Istingarra, Itzalpe, Aitzaki, Gizarta, and Ardatza (all founded in 1932), and Lagun Artea (1934).

The Spanish Civil War and Franco’s new regime slowed things down. By 1945 not a single new society had opened. The postwar development and new openings of popular and cooking societies have been described by Aguirre Franco (1983, p. 23) as less utilitarian and more aesthetic than their predecessors. But whatever happens in the future, it is now an acknowledged fact that San Sebastián’s cooking societies have not only had a remarkably successful history but have become the city’s distinctive modern trade mark. At the beginning of the new millennium, there were 120 cooking societies in San Sebastián, and the estimate is that one out of every 3.5 adults is a member of a sociedad (van Wijck, 2000). The popular society, especially the cooking society, has truly become the intersection of San Sebastián’s civic culture. Representing a form of being that includes many activities, it has even become a model for export.Footnote 5

The history of popular and gastronomic societies is somewhat different in Bilbao and its environs, located in the Basque province of Biscay (Basque, Bizkaia). Resulting from the long history of trade and commerce with England and the enormous affluence of Bilbao, popular establishments in this capital city first aspired to the ideal of the English Gentlemen’s club.Footnote 6

The difference between Bilbao and San Sebastián was indisputably one of both real and perceived wealth and class distinctions. A useful illustration is the history of Bilbao’s first popular society. Members of the Kurdin Club (established in 1899) tried to imitate the colonial lifestyle of the British (Aguirre Franco, 1983, pp. 60–61; Alonso Céspedes, 1996; Egin Monografias, 1996, pp. 2−3). Not only did they introduce sofas, boot stools, and marble tables to the society, but the drinks were also different, with cocktails and whiskies replacing cider and wine. That the whole enterprise was meant to be somewhat self-ironic and humorous becomes plain from the rituals of the members of the Kurdin Club. They had to wear caftans, imitate religious practices, and worship a certain holiness such as Martell, Hennessy, and Jimenez Lammothe (obviously, all brand names of hard liquor). The irony went even further, with clubs forming within the club: the Club de Hatchis, Club de Opio, and Club del Kiff. As the first rules of the Club stated, “Everyone does what he likes,” and the motto seems to be that one has to alienate oneself in order not to be alienated.

It would be wrong to assume from this example that class or wealth alone determined membership. True, the first wave of popular societies in Bilbao bore a greater mark of class distinction than the later waves have, but the subsequent development and history of the sociedades gastronómicas in the city and its environs still demonstrates that equal status within the society has remained the rule not the exception and that even the choice of a specific society has not been completely defined or determined by a particular class background. The difference between Bilbao and San Sebastián lies in a certain elevator effect. Class orientation in Bilbao has always been more pronounced than in San Sebastián. Places such as the Kurdin Club have been distinct and appealed, at least originally, to the rich bourgeoisie, a public very much apart.

The history of popular societies—above all, the cooking societies—in Biscay begins outside its capital, Bilbao. Their origins hark back to Biscayan seaside towns and harbors such as Ondarroa, Lekeitio, and Bermeo. As San Sebastián had done earlier, these settlements spread westward along the Cantabrian coastline (Alonso Céspedes, 1996, p. 28). Yet the first officially registered cooking society, Kili-Kolo, is further inland, in Durango. The oldest society in Bilbao, Gure Txoko, with 85 members, was founded fairly late in 1954. Shortly thereafter a second society was created, Txoko Bilboko Umore Ona. In the second half of the 1960s and early 1970s, a true boom ensued, the most prominent of these organizations being Achuritarra (founded 1965) with 200 members, Sociedad Recreativa Deusto (1967) with 150 members, and Abando (1970) with 100 members. At the turn of the previous century, Bilbao had 45 societies in total with an average of 30 to 60 membersFootnote 7 (Alonso Céspedes, 1996, p. 121). As in San Sebastián, most cooking societies in Bilbao can be found in the casco viejo (old part, old town) and in Uribarri and Santutxu. Elsewhere in the city, txokos seem to be evenly distributed, confirming again that popular space and related activities are not monopolized by a given urban elite. Outside Bilbao, cooking societies seem to be even more frequented than inside the Biscayan capital. Lekeitio, a small seaside resort, has 17 societies, whereas Bermeo, a slightly larger town than Lekeitio, has 33 (“Las 700 sociedades,” 1981).Footnote 8

Like Biscay, the province of Álava (Basque, Araba) and, most prominently, its capital, Vitoria-Gasteiz (hereafter referred to as Vitoria), took their lead and inspiration from Gipuzkoa and San Sebastián (Idroquilis, 1994). In contrast to cooking societies in Biscay, those in Vitoria developed as early as the 1930s. La Globa (founded in 1934 and having 100 members) was the first and largest cooking society, followed by El Rincon Amado with 30 members. Zaldibartxo was founded in 1941 in Sarria by Vitoria citizens; and Olarizu, founded in 1948, is known for a rather religious and aristocratic membership. In the 1950s there came Zaldiaran and San Juan-La Globa (both founded in 1953). Since 1988, Álava’s capital has been home to a federation of popular societies, Gasteizko Elkarteak, which started with eight societies and had grown to 27 societies as members by the end of the twentieth century. The overriding aim of the organization is to help organize the Fiesta de San Prudencia, including a tamborrada. Other activities include cooking competitions, wine competitions and tastings, and the Campeonato de Mus (Mus championship), the famous Basque card game. At the beginning of the twenty-first century there were 126 popular societies in Araba (including cooking and other recreational societies). Half of them are in Vitoria alone, mainly in the old part of this Basque capital (Idroquilis, 1994, p. 41).

In the province of Navarre (Basque, Nafarroako), the development of the sociedades conformed to the well-established cultural patterns of Basque settlements: more developed in the north and northeast and fizzling out or nonexistent in the south of the region (Aguirre Franco, 1983, p. 64). Navarre’s capital city, Pamplona has the highest number of these societies (15), the most prominent being Napardi and Txoko Pelotazale. Tafalla has 14; Tudela, 7; Elizondo, 5; and Alsasua, 4. Referring in Navarre almost entirely to cooking societies, the term sociedades is understood more narrowly there than in the provinces of Gipuzkoa and Biscay. In addition, the absence of women in the kitchens of Navarre’s cooking societies is conspicuous (Aguirre Franco, 1983).

In the late twentieth century the Basque Autonomous Community (Gipuzkoa, Biscay, and Álava) had 1,300 societies (Idroquilis, 1994, p. 17), but there are many more in Navarre and other Spanish cities and regions, especially in those locations where a significant number of Basques gather. In 1981 the Basque newspaper Deia reported that 50,000 Basques were members of cooking societies (“Las 700 sociedades,” 1981). The same newspaper reported that in one Biscayan seaside town, Lekeitio, around 80% of the male population attends a cooking society regularly. Today the cooking society has become a symbol of the Basque diaspora worldwide, and txokos can be found in almost any major capital or city that has a significant number of Basques, from Buenos Aires to New York City and London.

Formal and Informal Requirements: How the Txoko Comes to Life

For a common gastronomic society to function properly, basic institutional arrangements are necessary and a set of established rules have to be observed (Alonso Céspedes, 1996; Idroqilis, 1994; Luengo, 1999). In 1964 the Franco regime relaxed its attitude toward civil associations and organizations, introducing a new law of associations (ley de asociaciones). A 1965 by-law then specified possible applications and interpretations. Under the new rules each association or society had to state its place or location, the reasons or purposes for which the association or society existed, the social environment to which it appealed, the organization’s administrative structure, the rules of membership and access, and the rights and responsibilities of the members. The society or association also had to declare its nonprofit aims and specify the rules for its possible dissolution. The society or association also had to register officially as such with the Basque government, prove upon demand that it was adhering to the rules on such matters as official bookkeeping and documentation, and show, if necessary, that it was obeying the outlined regulations. The law of associations also used to require that the associations or societies abstain from politics, but today the democratic nature of societies and associations as a contribution to civil society is universally acknowledged.

The legal framework addresses only minimal formalities and structural requirements of a given society. What is absolutely essential for a society to function is a proper infrastructure. A gastronomic society affords an infrastructure like that of a restaurant, but it is not open to the public, only to the society’s members or their guests. Another difference is the arrangement between the kitchen and the dining area. The kitchen is usually open or semiopen, not completely separate or out of sight as in restaurants. The kitchen includes everything necessary to prepare food for sizable groups: two or three ovens, including open fireplaces or grills; cooking utensils; freezers; and refrigerators. Some societies have more than one kitchen and more than one room for the preparation and consumption of food.

Seating for relatively big groups is available at one long, square, or round table, though tables appropriate for smaller gatherings exist as well. A society also has cleaning equipment, bathrooms, and, most important, space to store the wherewithal regularly needed for preparing and consuming food (including the basics, such as salt, pepper, oil, and a well-stocked bodega, or wine cellar). Most societies also have full bar facilities, along with coffee and espresso machines.

The cooking itself is ordinarily done voluntarily and almost always rests on experience. In other words, the members with a history of excellence do the cooking. The cook’s experience often stems from performance in other circumstances, such as having cooked on a ship or other vessel, for ceremonies or fiestas, or at the baserri (Basque, “farmstead”). The cook’s only reward may be a common toast or word of acknowledgement from other members or guests.

After the preparation and the meal, the digestivo is served and a bill is written. The people who have partaken in the meal have to pay pro rata. Because the society has supplied the basic infrastructure for consumption and because all the work (buying, preparing, cooking) was voluntary and based on an honor system, the bill is far below the price of an average restaurant meal, probably even less than that of a home-cooked meal. Most of the purchases for the meal are handled through well-established contacts, for members of the society know their local providers and buy directly from them, avoiding the market. Members of the society often happen to be fishermen, happen to work in a baserri, or know somebody who does and who can thus sometimes offer the basic ingredients (the fish, the meat) for free or at cut-rate prices. Depending on individual expenses and purchase practices, the bill is sometimes split so that buyer-members can be reimbursed. Yet as a rule one pays pro-rata, and the money thereby collected is placed with an itemized bill into an envelope and is then sent to the treasurer of the society through the internal mail system or put into a cashbox, the cajetin (to be collected later by that person).

A society’s life needs a legal framework and a location. However, the txoko comes to life only because it is an institutional expression of a much more widespread social phenomenon: the cuadrilla (clique, circle of friends) (Arpal Poblador, 1985; Ramirez Goikoetxea, 1985). The cuadrilla is the result of a complex shift or transfer from a rural environment to complex urban structures. The interaction between the txoko and the cuadrilla deserves a detailed explanation.

To understand the phenomenon of the cuadrilla, it is first necessary to comprehend the part that the kale (street) plays in Basque culture (see Arpal Poblador, 1985, pp. 131−145). To do so, one must distinguish between a rural and an urban form of social life in the Basque Country (p. 132). In the countryside one finds the etxe (rural house, farmstead), which is agricultural and private in character. Its social type is the baserritarra, the man or woman who lives the rural life. Rural life generally denotes being somehow closer to nature or living in a natural environment that remains healthy and unspoiled. By contrast, life in the city or town is symbolized by the kale, which is by definition open to the public. This urban life is embodied mainly by the kaletarra, the man or woman who lives in the street. Life in an urban environment, be it the town or the city, denotes culture or civilization. It is regarded as artificial, not natural, and therefore associated with values that refer to less-than-wholesome aspects of life. Until the nineteenth century the people of the Basque Country were familiar with only very limited urban development typified by towns having but three streets: la de arriba, la de enmedio, and la de abajo (upper, middle, and lower street) and the houses along those streets (Arpal Poblador 1985, p. 132). Only three sizeable urban centers, developed (Bilbao, Vitoria, and San Sebastian), but even there the old quarters had no more than half a dozen streets, with the plaza (square) often being outside the casco viejo. Beyond the old center other urban settlements, the ensanches, did not form until later. Apart from the casa solar (isolated, free-standing rural home), many rather wealthy farmsteads had la casa en la calle, a house in the town, so the countryside often extended into town (Arpal Poblador, 1985, p. 134). This image of the street in front of the caserio (small farm) can be considered an indication of a continuous conflict that blurred some of the boundaries between countryside, village, town, and city. Only with the turn of the twentieth century did the situation change. But in an age when urban centers and urban life have come to dominate modern Basque society, one can still encounter symbolic representations of rural life in most Basque towns and cities. Analysts have referred to a complex situation in which “symbolic transfers” (Arpal Poblador, 1985, p. 135) from a rural to an urban environment are still common. Its symbol is the “urban villager,” who has emerged as a new social type and who combines elements of both baserritarra and kaletarra.

The urban villager’s key social reference point is the cuadrilla, a social formation defined by certain characteristics common to the individuals constituting the group: the same generational cohort, the same gender, or the memory of playing together in the same street or barrio (neighborhood, quarter) where they grew up. Crucial are those shared experiences or rites of passage that usually mark an individual for life but also foster the entire group’s collective memory, such as the ikastola (the Basque language school), military service, and important political events. However, the function of the cuadrilla has evolved and changed over time. During the Franco years and even during and after the post-Franco political transition, the cuadrilla constituted a social infrastructure, a civil-society response that functioned as a stable factor in an unstable political environment. The cuadrilla established a kind of parallel world engendering the trust, friendship, responsiveness, and equality in communication, a stability in everyday life that the Franco regime and the exceptionally turbulent post-Franco transition in the Basque Country could not grant (Perez-Agote, 1984, pp. 105−123). Since the late 1990s, however, the cuadrilla phenomenon has changed. Whereas the privatization of social life (Perez-Agote 1984, pp. 105−123) opened an escape route during the Franco era and the transition from it, functions other than sheer resistance to the political system have meanwhile become important.

According to sociologist Jesus Arpal Poblador (1985, pp. 136−154) in his brief phenomenology of a typical cuadrilla’s life today, the group, usually 5 to 10 people, gathers to spend time and go places as the collective ritual demands. The group meets regularly for drinks, the txikiteo or poteo, usually either before lunch or before dinner or on other occasions as determined by the festivity calendar or specific occasions such as birthdays or anniversaries. The txikiteo consists of making a round through the different bars of a specific zone or barrio, which in most cities is located in the casco viejo. Taking place almost daily, the poteo may seem almost compulsive to an outsider. The movement and appearances of some cuadrillas have sometimes become such an established pattern that the bartender no longer needs to hear the order.

Just as the cuadrilla leaves its mark on the vicinity, the vicinity, or a given spatial environment, marks facets of the group’s habit. One of the most interesting aspects of the cuadrilla phenomenon, though, is that it does not impose unanimity. It is a collective phenomenon that allows time and space for individual expression and creativity. As with any group, various roles evolve within the group; leaders arise who are more popular and acknowledged than others. In some cities and towns these persons have even acquired nicknames that have become so popular that the individual is known only by that name. To gain the respect of one’s friends, it is crucial to remain genuine and true to oneself. Some members are known only by their unique appearance, character, or other authentic attitude or history.

Txokos are manifestations of well-established social contacts, principally of the cuadrilla type. The txoko and the social relations that it represents are a means of reconstituting the reciprocity relations that have their origins in more traditional forms of life, yet they are essentially new in that they represent a modern form of social relations in a growing and increasingly influential urban environment. Originally a peculiar invention of San Sebastián’s bourgeoisie, the popular societies, notably the gastronomic societies (Arpal Poblador, 1985; Luengo, 1999), have, over roughly a century, become less class representative or class bound and are now a more inclusive and interclass phenomenon than ever before. The txoko in its ubiquity now fulfills a variety of positive societal functions. As argued by Arpal Poblador (1985, p. 138), mechanical solidarity and space that are created for the individual together with a communitarian dimension contribute to a social equilibrium. Txokos are thus an institutionalized measure and increasingly an “interclass phenomenon” (Arpal Poblador, 1985, pp. 140−141; Luengo, 1999) against the divisions of modern society, an attempt to introduce a form of integration based on what Habermas and others have called Lebenswelt (life world). Ranging somewhere between tradition and modernity, the life world is an attempt to respond to purely instrumental and systemic rationalization and integration. But the txoko not only has liberating functions; it also reproduces existing age and sex or gender constellations and often presents society as if it were a community (Arpal Poblador, 1985, pp. 140–141). Some commentators have interpreted the txoko as an institutional compensation device that exercises a cooling effect on an overheated society and lessens tensions through a collective group therapy almost resembling a psychodramatic setting. This interpretation suggests that the txoko offers an escape route from the necessities of daily life, implying not only a shift toward communality and commensality (the act of eating together) but almost an exit strategy (Aguirre Franco, 1983; van Wijck, 2000).

Yet it would be wrong to perceive the function of the txoko solely in extreme terms or in the light of total exit conditions. As an institution, it is as good (or bad) as the society and the members who support it. The fact remains that eating at the txoko, particularly during the fiestas, interrupts daily life and routine and definitely conveys what Simmel (1971) termed conviviality (pp. 127–129). But the txoko as an institution is more than that. As a symbolic reproduction of Basque society and identity, the txoko accommodates the transition from rural to urban life, exemplifying a historic reformulation of the community–society divide (Arpal Poblador, 1985; Ramirez Goikoetxea, 1985). As potential cells for reproducing nationalism, the cuadrilla and the txoko together can also be seen as models of sociability and commensality not bound by rigid class structures, as elements that link classes instead (Luengo, 1999; Perez-Agote, 1984). Lastly, if Luengo (1999) is correct that investigating the levels of sociability is almost like using a thermostat to analyze change in society, then the txoko phenomenon, particularly its recent enormous expansion, may indicate that Basque society is becoming more inclusive and thus more democratic than it has been. Enriching the public sphere, yet not in an anonymous, impersonal, or entirely privatized way, the txoko has helped reconstruct the social fabric of a community that is otherwise deeply politically divided. In the eyes of at least one commentator, it has also afforded a real alternative to the homogenization process of modern capitalist society (Ramirez Goikoetxea, 1985).

Between Homogenization and Differentiation

Having examined the history and microlevel operations of the cooking societies, I now look at broader issues, namely, the ways in which cooking, eating, and drinking together in the txoko are linked to some of the region’s physical, cultural, and historical features. It is impossible to discuss social aspects of the txoko such as conviviality and commensality unless the question of what the members actually eat and drink when they are together is combined with the historiogeographical question of why they do so particularly in the Basque Country. There is no human activity in which function and content are as interdependent as eating and drinking. Form is indeed condensed substance, and full appreciation of the formal aspects of eating together in the cooking society requires at least a brief historical account of alimentation, nutrition, and cooking, the content that is often linked to unique historiogeographical patterns in the Basque Country.

Overall, Basque cooking has always reflected the old division between the Atlantic North and the Mediterranean South (Iturbe & Letamendia, 2000, p. 48). Developed forms of agriculture have always been limited in the Atlantic zone, primarily because of its rugged terrain and humid climate. Fishing is omnipresent, and the supply of meat and fat generally comes from farm animals such as chickens, goats, lambs, and cows. Standard beverages are alcoholic drinks, apple cider, and some white wine (txakoli from microclimates and terroirs such as those in Getaria, Gipuzkoa). By contrast, the southern zone has a rather dry climate and a less rugged, more extensive and farmable terrain that allows for the development of sophisticated crops, such as asparagus, spinach, artichokes, and cereals. Inland, large-scale farming and a cattle industry emerged in the course of the nineteenth century. In terms of nutritional models and cuisine, the fat comes chiefly from olives, not animals. And unlike the Atlantic zone, the south has sophisticated wine-making, above all in parts of Álava and Navarre. The different geographical patterns explain the availability and the peculiar choice of food in the txokos of each zone or region. Fish and seafood are found everywhere in the Atlantic zone, whereas meat and vegetables are more likely to make it onto the menu in the southern zone (e.g., Álava and Navarre). By the same token, the choice of wine is distinct to each zone or region, white wine from Getaria or Galicia is more likely to be consumed in txokos located in coastal communities, whereas the top-rank red Riojas or the best Navarrese wines are more likely to be consumed where they have been produced.

Over time three main influences have changed food-consumption patterns in the Basque Country. First, alimentation changed radically through the discovery of the New World and the introduction of New World produce such as corn, potatoes, pepper, tomatoes, beans, sugar, and chocolate to the northern and southern zones. Corn, beans, and potatoes were exceptionally influential on nutritional patterns (Busca Isusi, 1987, pp. 13−17; Haranburu Altuna, 2000, pp. 161−162; Iturbe & Letamendia, 2000, pp. 50−52).

The second most important influence was the Catholic Church. It established a religious calendar, which prescribed what foods to avoid and what to eat at which times (Haranburu Altuna, 2000, pp. 118−165, pp. 201−202; Iturbe & Letamendia, 2000, pp. 52−57). Religious abstinence demanded the exclusion of meat, meat soup, eggs, milk products, and animal fat. Abstention was practiced on Wednesdays and Fridays, along with other selected days of the year. On the remaining days, fish was the alternative. Basque society and culture today are much more secularized than they used to be. But secularization does not mean that old consumption habits stemming from a Catholic background have completely disappeared. It is still the tradition in many household kitchens and txokos to have fish or seafood around Christmas and the New Year, whereas meat and related dishes are standard on some days of the fiesta. The calendar of festivals is full of days celebrating saints, occasions that call for a certain form of cooking. Additionally, there are birthdays, weddings, retirement, stag nights, and funerals, events that ordinarily determine the choice of what to eat and drink. However, the Catholic church emphasized and actively promoted communitarian habits of eating not only to mark such special events but also to ward off the threat of Protestant individualism. Eventually, eating together, religious belief, and social life developed into a custom, as illustrated by that institutional microcosm, the txoko.

The third impact on eating habits and food consumption in the Basque Country came with the modernization of the region’s society at the turn of the twentieth century. Especially important was the development of a modern infrastructure (installation and improvement of rail and road networks) and the means of communication (the telegraph, the telephone, and, later, radio and film). Such advances nurtured a modern tourist industry. Combined with industrialization, they resulted in the creation of an urban, industrialized environment and culture. Such changes immediately yielded a new landscape of political cultures. The liberals favored the nascent rationalized form of urban culture, notably in Bilbao and San Sebastián, whereas the traditional rural way of life was besieged by modernization and rationalization processes (Iturbe & Letamendia, 2000, pp. 59−63). The conflict between the two opposing forces eventually gave way to a new, third force, Basque nationalism. Blending aspects of both conservatism and modernization, it had a particular impact on the cuisine and food patterns. Basque nationalism aimed to reconstruct what it means to be Basque, so symbolic capital such as food and the act of eating together became a major focus (p. 62).

The traditional style of rural food preparation and consumption, the urban standardization of cooking in such places as hotels and restaurants, and the nationalist attempt at reconstructing culinary symbolic capital all played a part in producing a new common cuisine to which the new label cocina vasca truly applied and for which txoko cooking has become an institutional expression. What makes this new constellation so remarkable is the convergence of two processes: homogenization and differentiation (Haranburu Altuna, 2000, pp. 299−305). The homogenization process is unmistakable in the Mediterraneanization of food in the Basque Country, with the olive-based alimentation of the Ebro valley reaching the Cantabrian coast and now prevalent in the Atlantic provinces of Gipuzkoa and Biscay. At the same time, modern transportation and food preservation have made it possible for the fresh fruit and fish of the Atlantic to spread to Navarre and Álava—to such an extent that they are now thought of as staples. Such homogenization has not led to total monotony or dominance, though. Variety and diversity has always existed in the regions. In fact, some people have called for changing the label cocina vasca to its plural, cocinas vascas, to reflect regional differentiation (Haranburu Altuna 2000, p. 30).

With respect to the development of alimentation and cooking over the last twenty years, modernization and rationalization processes have culminated in what has been referred to as the new Basque cuisine, la nueva cocina vasca. The development of the new Basque cuisine is arguably a critique of the rationalization process as it has developed so far. For lack of anything new, adventurous, or surprising on the standard menu or ways of preparing and presenting it, this new movement has pressed for a return to culinary basics and an end to the process of saturation and stagnation. The demand has also been for fresh produce. The avant-garde of this culinary revolution has consisted largely of innovative restaurant chefs and cooking-society experts. (These roles often overlap in the Basque Country.) The history of the new Basque cuisine has been truly revolutionary and so successful that most of the more sophisticated Basque restaurants and txokos have incorporated its demands. Throughout the year (mainly during the fiestas but by no means limited to them), the Basque Country now has numerous competitions in which txoko cooks continue the innovation and refinement of Basque cooking. They are aided by thousands of txoko members and guests who all think they would not enjoy the cocina vasca if cooking and eating were isolated or solitary affairs.

Between Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft: Plebeian Culture, Moral Economy, and Commensality

In his writings on late eighteenth-century England, E. P. Thompson (1980, 1991) suggested that plebeian culture and moral economy are intrinsically linked. Plebeian culture was an auxiliary term that Thompson used to describe a situation in which class was not what classic Marxist theorists assumed it to be. Rather than forming nascent prototypes of the industrial working class, Thompson preferred to see classes as fields of gravity, as heterogeneous constellations of many dimensions and layers in which traditional popular customs played a major part. These common customs also facilitated the survival of a moral economy, one that could assume various meanings to the plebeian crowds, including shared rights, norms or obligations, day-to-day habits, and practices. Taken together, these meanings in many ways constituted a force alien and opposed to elite classes.

A closer look into the stratification of the Basque Country reveals few, if any, clear-cut class structures, except in the metropolitan region of Bilbao, its industrial environs, and a few industrial towns and industrial development zones such as Durango, Eibar, Elgoibar, Ermua, and Hernani. In many ways the Basque Country seems a prime illustration of Thompson’s (1980) main notion of plebeian culture. The work of social historians and historical anthropologists repeatedly cited in this chapter, such as Luengo (1999), Homobono Martínez (1987, 1990, 1997), and Arpal Poblador (1985), confirms the existence of such a plebeian cultural macroconstellation and the place that cooking societies play in its moral economy.

Whereas historians and social scientists have hinted at these kinds of macroconstellation and the moral economy that goes with them, the political economist Albert O. Hirschman has looked at microconstellations, by which he mainly meant institutional dimensions. In The Passions and the Interests (1977) he first hinted that passions and interests might be much more intrinsically linked in modern times than has often been assumed. Concepts derived from his approach to moral economy, above all the idea of commensality (Hirschman, 1998, pp. 11−32), allow the researcher to take a closer look at the microlevel and the peculiar links that exist between the public and the private sphere and between customs and morals (Hess, 1999).

In his seminal book Shifting Involvements: Private Interest and Public Action (1982), Hirschman addressed the problem of periodic shifts that have occurred in modern civil society. In this work he analyzed both the retreat into privacy and the inclination toward public action in wave-like appearances. He found that a sense of disappointment was the main motive behind both private retreat and public action. At that time Hirschman did not discuss social practices in which public concern mingles with private activities and thereby fosters an equilibrium in civil society. Going a step further, Hirschman maintained that merging the private and public spheres was seen as a potential threat to civil society. In his much later essay about commensality, Hirschman (1998) revisited some of his previous arguments. He asked the reader to think about occasions where the merging of the two spheres can actually have positive results and pointed out that “economists [and other social scientists] have often looked at the consumption of food as a purely private and self-centered activity” (p. 28).

Hirschman (1998, p. 29) continued his argument by stressing that social scientists usually forget about other dimensions: While people are consuming food and drink, they gather for the meal, engage in conversation and discussion, exchange information and points of view, tell stories, perform religious services, and so on. From the purely biological stance, there is no doubt that eating has a straightforward relationship to individual welfare. But once eating and drinking are done in common, they normally go hand in hand with a remarkably diverse set of public or collective activities.

Hirschman (1998) further stressed that the function of the common meal can, and really does, vary. He brought to mind Heinrich Mann’s novel Der Untertan (The Subject), in which the main character, Diederich Hessling, is drawn into a form of beer-drinking and pretzel-eating commensality that can be described only as reactionary in terms of its later outcome, National Socialism. In contrast to such negative examples and experiences, Hirschman then revealed the great potential of commensality: noninstrumental, ends-oriented interaction. It is exactly at this juncture that the Basque cooking society comes in. It seems to me that the txoko is a positive example of how commensality, at least when collectively organized and sensibly institutionalized, can cultivate loyalty and help maintain a civic equilibrium. In other words, when such commensality emerges, human beings are not treated merely as means to certain ends but rather as ends in themselves.

Constituting the microinstitutional framework for such ends-centered interaction, the txoko promotes the social equilibrium. Txokos are an institutionalized measure and increasingly an interclass phenomenon working against the divisions of modern society. In other words, they are an attempt at life-world integration (Arpal Poblador, 1985; Habermas, 1962; Luengo, 1999). Located somewhere between tradition and modernity, txokos are attempts to provide answers to purely instrumental and systemic rationalization or system integration. However, unlike public institutions and the public sphere in the roles that Habermas emphasizes and endorses, txokos are neither purely public nor purely private institutions. Instead, they occupy a unique space somewhere in the middle of that continuum. It is this intermediate position that enhances the success and popularity of the txokos.

Yet not all the txoko’s social functions are “progressive.” Ultimately, it is as an institution as good (or as bad) as the society and the members who constitute it. The txoko is clearly an expression of conviviality as meant by Simmel (Homobono Martínez, 1987). In that sense the txoko as an institution is also a symbolic reproduction of Basque society and identity and is especially accommodating of the transition from rural to urban life. It thus exemplifies a historic reformulation of the community–society divide (Arpal Poblador, 1985).

Whatever the details and the individual and collective enjoyment in the sociedades are, this institution has obviously become a backbone of modern Basque society. Unlike the disastrous experiences with certain forms of collectivity in the former Soviet Union and Nazi Germany (as totalitarian social and political regimes that tried to eliminate the distinction between private and public), Basque cooking societies exemplify interaction through which the public and the private actually enrich each other. It seems wrong to me to degrade these organizations as being part of an invented tradition or to consider them terrorist recruitment cells or nationalist inventions, as is sometimes implicitly suggested by commentators like Juaristi (1987) and Hobsbawm and Ranger (1983). The opposite is true. The sociedades gastronómicas are relatively modern institutions that allow the Basque Country to overcome some of the tensions that arise when an old civilization meets the modern conditions of the twenty-first century. The relationship between the private and the public is a delicate one, and has not always worked out well in modern times. The txoko, which uniquely connects both spheres, does appear to be the Basques’ most genuine and beneficial reply to the question of how a plebeian culture with a long history can survive under modern conditions.

As I have tried to show, the gastronomic society is unique to Basque society and its historical, cultural, political, and social conditions and its geographic environment. Although the Basque diaspora has partly transported such gastronomic practices to other parts of the world, it remains largely a Basque affair (visitors are always welcome). I therefore remain skeptical about the possibility of transplanting or copying such habits and practices. Emulation is always a possibility, of course. Yet with all the media hype about cooking in recent years, it remains to be seen whether the appropriate cultural and social forms and conditions can be found outside the Basque Country. After all, the purpose is not only that of consuming all that good food and drink but also of doing so for the beneficial and mutual effect on those who regard eating and drinking not just as solitary, entirely private affairs but as social and cultural acts.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

According to Luengo (1999), San Sebastián’s class structure in 1911 was made up of artisans (28.27%); members of the new working class (18.95%); employees and administrators (10.32%); proprietors, industrialists, and members of the independent professions (7.01%); and fishermen, rural employees, clerics, and military personnel (19.43%). The unique constellation, in which the classic industrial working class is underrepresented but various subaltern classes together constitute something like a working plebe, justifies reference to the term plebeian class structure (Thompson, 1980). For a detailed discussion of such class relations, see the final part of this chapter.

- 3.

Both Luengo (1999) and Aguirre Franco (1983) have stressed that the popular societies usually restricted only the overall size of their membership and that any class discrimination therein was unheard of. Gender- and sex-related exclusionary practices prevailed in the early history of the popular societies but became less restrictive over time (see this chapter’s discussion of the general function of the sociedades). Nonetheless, Unión Artesana, one of the oldest societies, remains exclusively and explicitly male.

- 4.

In one famous, well-documented anecdote, the famous Basque writer Pio Baroja had been invited to Gaztelupe, one of the best-known sociedades, but had found the experience wanting after he had been shown the library—the name that members had given to the society’s bodega.

- 5.

Historically, the phenomenon first spread to other Gipuzkoan towns, notably those just a short ride away from San Sebastián. The 1920s and early 1930s saw the opening of cooking societies in Tolosa (Gure Kaiola in 1927 and Gure Txokoa in 1931), Zumarraga (Beloqui in 1929), and Zarautz (Gure Kabiya in 1931).

- 6.

That the English represented an ideal is evident from the history of the city’s soccer club, Athletic Bilbao—not Atletico Bilbao.

- 7.

Contravening the overall tendency to include women, txokos in Bilbao seem to remain almost exclusively male. Meritxell Alonso Céspedes (1996) reported that only two of the 45 txokos that she visited officially welcomed women as members. This statement appears to be confirmed by a report filed by the Diputación Foral de Vizcaya, which researched how many women participated in voluntary associations. The group found that only 0.7% of all respondents stated they participated in a gastronomic society (as cited in Alonso Céspedes 1996, p. 121).

- 8.

In his ethnographic work on Bermeo, Homobono Martínez (1987; 1997) dated the first txoko back to the mid-1960s. Txokos spread with astonishing rapidity in the 1970s. In Bermeo alone, 36 of them were founded. According to the 1981 newspaper account in Deia, Bermeo had the second highest number of txokos in Biscay (after Bilbao). Homobono Martínez (1987) pointed out that most members came from the fishing sector (p. 350).

References

Aguirre Franco, R. (1983). Las sociedades populares [Popular societies]. Colección Guipúzcoa: Vol. 19. San Sebastián: Caja de Guipúzcoa.

Alonso Céspedes, M. (1996). El caso de los txokos vascos: Sociología de la fratría informal [Basque txokos: A sociological case study on informal fraternities] (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universidad de Deusto, Bilbao, Spain.

Arpal Poblador, J. (1985). Solidaridades elementales y organizaciones colectivas en el país Vasco (Cuadrillas, txokos, asociaciones) [Primal solidarities and collective organizations in the Basque Country (Cliques, gastronomic societies, associations)]. In P. Bidart (Ed.), Processus sociaux: Idéologies et practiques culturelles dans la société basque (pp. 129−154). Pau: Université de Pau et des pays de l’Adour.

Busca Isusi, J. M. (1987). Traditional Basque cooking. Reno: University of Nevada Press.

Habermas, J. (1962). Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit [The structural transformation of the public sphere]. Darmstadt: Luchterhand.

Haranburu Altuna, L. (2000). Historia de la alimentación y de la cocina en el País Vasco [History of food and cooking in the Basque Country]. San Sebastián: Hiria Liburuak.

Hess, A. (1999). ‘The economy of morals and its applications’—An attempt to understand some central concepts in the work of Albert O. Hirschman. Review of International Political Economy, 6, 338−359. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/096922999347218

Hess, A. (2007). The social bonds of cooking: Gastronomic societies in the Basque Country. Cultural Sociology, 1, 383−407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975507082056

Hess, A. (2009). Reluctant modernization: Plebeian culture and moral economy in the Basque Country. Oxford, UK: Peter Lang.

Hirschman, A. O. (1977). The passions and the interests: Political arguments for capitalism before its triumph. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hirschman, A. O. (1982). Shifting involvements: Private interests and public action. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hirschman, A. O. (1998). Crossing boundaries—Selected writings. New York: Zone Books.

Hobsbawm, E. J., & Ranger, T. (Eds.). (1983). The invention of tradition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Homobono Martínez, J. I. (1987). Comensabilidad y fiesta en el ambito arrantzale: San Martin de Bermeo. [Socializing and celebrating in the company of fishermen]. Bermeo, 6, 301−392.

Homobono Martínez, J. I. (1990). Fiesta, tradición e identidad local [Celebration, tradition, and local identity]. Cuadernos de etnología y etnografia de Navarra, 55, 43−58. Retrieved from http://www.vianayborgia.es/bibliotecaPDFs/CUET-0055-0000-0043-0058.pdf

Homobono Martínez, J. I. (1997). Fiestas en el ámbito arrantzale. Expresiones de sociabilidad e identidades colectivas [Celebrating in the fishing sector: Manifestations of commensality and collective identities]. Zainak, 15, 61−100. Retrieved from http://www.eusko-ikaskuntza.org/en/publications/fiestas-en-el-ambito-arrantzale-expresiones-de-sociabilidad-e-identidades-colectivas/art-9041/#small-dialog

Idroquilis, A. P. (1994). Comer en sociedad [Eating together]. Vitoria-Gasteiz: Diputación Foral de Álava.

Iturbe, J. A., & Letamendia, F. (2000). Cultura, politica y gastronomia en el País Vasco [Culture, politics, and gastronomy in the Basque Country]. In F. Letamendia & C. Coulon (Eds.), Cocinas del mundo—La politica en la mesa (pp. 45−78). Madrid: Editorial Fundamentos.

Juaristi, J. (1987). El linaje de Aitor. La invención de la tradición vasca [The lineage of Aitor: Inventing the Basque tradition]. Madrid: Taurus.

Las 700 sociedades gastronomicas en Euzkadi siguen siendo un coto privado para hombres [The 700 gastronomic societies in the Basque Country remain a private preserve for men]. (1981, October 30). Deia (Bilbao).

Luengo [Teixidor], F. (1999). San Sebastián—La vida cotidiana de una ciudad [San Sebastián—The daily life of a city]. San Sebastián: Editorial Txertoa.

Perez-Agote, A. (1984). La reproducción del nacionalismo. El caso Vasco [The social roots of Basque nationalism]. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Ramirez Goikoetxea, E. (1985). Associations collectives et relations interpersonelles au Pays Basque [Communal associations and interpersonal relations in the Basque Country]. In P. Bidart (Ed.), Processus sociaux: Ideéologies et practiques culturelles dans la société basque (pp. 119–128). Pau: Université de Pau et des pays de l’Adour.

Simmel, G. (1971). On individuality and social Forms (D. N. Levine, Trans.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Thompson, E. P. (1980). Plebeische Kultur und moralische Ökonomie [Plebeian culture and moral economy]. Frankfurt: Ullstein.

Thompson, E. P. (1991). Customs in common: Studies in traditional popular culture. London: Merlin Press.

Tocqueville, A. de (2000). Democracy in America (H. C. Mansfield & D. Winthrop, Trans). 2 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1835–1840)

van Wijck, A. (2000). Basque male cooking societies (Unpublished master’s thesis). Boston University, Massachusetts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

<SimplePara><Emphasis Type="Bold">Open Access</Emphasis> This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.</SimplePara> <SimplePara>The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.</SimplePara>

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hess, A. (2018). Gastronomic Societies in the Basque Country. In: Glückler, J., Suddaby, R., Lenz, R. (eds) Knowledge and Institutions. Knowledge and Space, vol 13. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75328-7_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-75328-7_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-75327-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-75328-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)