Abstract

This chapter undertakes the task of clarifying the composition and boundaries of the twilight zone of institutions, activities and behaviors that lie beyond the market, the state and the family and is variously called the “third sector,” “civil society,” or “social economy.” Building on a bottom-up process of consultation, literature review and analysis carried out by a broad team of European analysts, the chapter advances a conceptualization of this sector that embraces both institutional units and individual-action components that embody three underlying attributes: (a) they are private, (b) they are primarily oriented to the public good and (c) they are noncompulsory. These attributes are then translated into an operational definition that is suitable for incorporation into official statistical data gathering and that clearly identifies a broad in-scope array of nonprofit, cooperative, mutual and social-enterprise organizations as well as a parallel band of both organization-based and direct volunteer activity undertaken without pay for persons outside one’s family. The chapter then concludes with a discussion of the progress that has already been made toward institutionalizing this definition into the System of National Accounts, which guides the official assembly of comparable economic statistics in countries throughout the world.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

In calling for a study of the scope, scale and impact of the third sector in Europe, the authors of the tender that led to the present book wisely emphasized that “stock-taking presupposes conceptual clarification,” and set the project out on a search for a consensus conceptualization of the uncharted social space beyond the market, the state and the household thought to encompass the third sector. While there was some agreement about what this sector was not, however, there was no clear agreement about what it included, or what it should be called. An earlier first step toward clarifying the boundaries and content of this twilight zone focused on what is widely considered to be at its core—the set of institutions and associated behaviors known variously as associations, foundations, charitable giving and volunteering; or collectively as nonprofit, voluntary, voluntary and community, or civil society organizations and the volunteer activity that they help to mobilize (Salamon et al. 2004, 2011). Even this was a herculean conceptual task, however, given the bewildering diversity and incoherence of the underlying realities this concept embraced. But no sooner did a consensus form around how to define this core than a chorus of critics surfaced calling attention to an even wider network, not only of institutions and individual behaviors, but also of sentiments and values they claimed had legitimate claims to be considered parts of the third sector domain, at least in Europe if not the entire world (Evers and Laville 2004). And now, perhaps not surprisingly, a know-nothing perspective has surfaced in some quarters challenging the entire objective of conceptualizing and mapping this twilight zone on grounds that it is certain to serve chiefly the nefarious and anti-democratic objectives of state actors and therefore cause actual harm and offer little benefit to the institutions and individual behaviors included or those who benefit from their activities (Nickel and Eikenberry 2016: 392–408).

Against this background, the task to be undertaken in this chapter—to take the next steps in clarifying the composition and boundaries of the twilight zone of institutions, activities and behaviors that lies beyond the market, the state and the family—may appear to be a fool’s errand, unlikely to succeed and likely to tarnish the reputations of its authors and cause harm to its putative beneficiaries even if it does achieve its goal. While we certainly concede that conceptualizing and mapping what we here term the “third,” or the civil society, sector can serve the control objectives of states, we believe equally strongly that they are at least as likely to empower, legitimize, popularize and validate the behaviors and institutions that operate in this social space and potentially lead to public policies supportive of these institutions and behaviors, rather than only harmful ones.

More than that, we believe that clear and understandable conceptual equipment remains one of the sorest needs in the social sciences, and nowhere more than in the somewhat embryonic field of third sector studies. Indeed, as one of us has written in another context: “The use of conceptual models or typologies in thinking is not a matter of choice: it is the sine qua non of all understanding” (Salamon 1970: 85). Political scientist Karl Deutsch made this point powerfully in his Nerves of Government, when he wrote: “we all use models in our thinking all the time, even though we may not stop to notice it. When we say that we ‘understand’ a situation, political or otherwise, we say, in effect, that we have in our mind an abstract model, vague or specific, that permits us to parallel or predict such changes in that situation of interest to us” (Deutsch 1962: 12). It is for this reason that Deutsch argues that “progress in the effectiveness of symbols and symbol systems is thus basic progress in the technology of thinking and in the development of human powers of insight and action” (Deutsch 1962: 10).

Anyone who has followed the development of understanding of the third sector in all of its manifestations must recognize this need for “basic progress in the technology of thinking” in this field. Accordingly, this chapter describes an effort undertaken by a team of scholars to take the next step in conceptualizing this broad sphere of social activity. More specifically, it presents a consensus definition of what for the sake of convenience we refer to as “the third sector” and that later in this chapter we will propose referring to as the TSE sector for reasons that will become clear there.

This conceptualization took advantage of the widespread bottom-up investigation carried out in more than 40 countries scattered widely across the world in the process that led to the conceptualization of the “nonprofit sector” in the Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project, but supplemented this with a similar bottom-up investigation carried out in the context of this project in a broad cross-section of European countries—north, south, east and west—to tap understandings of the broader concept of a “third sector” and its various regional cognates, such as social economy, civil society and social entrepreneurship. Building on these bottom-up processes, a consensus conceptualization was hammered out through a vigorous set of discussions among representatives of 11 research institutes, and then further reviewed by the project’s advisory board, sector stakeholders and participants in two academic conferences. The goal was to provide as broad a consensus conceptualization as possible, and one that could provide a basis for systematic comparisons among European countries and between them and countries in other parts of the world, and that could be institutionalized in existing official statistical systems and used to generate reliable data on this sector on a regular basis.

To introduce this proposed conceptualization, the discussion here falls into five sections. Section 1, which follows, describes the basic challenge that stands in the way of developing a coherent, common conceptualization of the third sector that can work in a wide assortment of countries and regions, and explains why it might be important for this sector to overcome these challenges. Section 2 then outlines the strategy we employed to find our way around these challenges with the help of a team of colleagues. In Sect. 3, we summarize the major conclusions that emerged from the fact-finding and discussion processes undertaken in pursuit of this strategy. In Sect. 4, we present the key elements of the much-broadened consensus definition of the third sector that resulted, focusing first on the institutional components of this sector and then on the individual activity components. The final section outlines the next steps that will be needed to move toward the development of basic data on the third sector so conceptualized—both in Europe and more broadly—and the progress that has been made in this direction as of this writing.

1 The Challenge

1.1 A Diverse and Contested Terrain

The starting point for our conceptualization work was naturally the existing diversity of views over whether something that could appropriately be called the “third sector” actually exists in different parts of the world and, if so, what it contains. Even a cursory review of the literature makes it clear that the “third sector,” and its various cognates, is probably one of the most perplexing concepts in modern political and social discourse. It encompasses a tremendous diversity of institutions that only relatively recently have been perceived in public or scholarly discourse as a distinct sector, and even then only with grave misgivings given the apparent blurring of boundaries among its supposed components.

Some observers adopt a very broad definition that, in addition to organizations, includes the actions of individuals and societal value systems (Heinrich 2005). Others prefer more narrow definitions, focusing, for example, on “nongovernmental” or “nonprofit” or “charitable” organizations. Other definitions fix the boundaries of this sector on the basis of such factors as the source of organizational income, the treatment of organizational operating surpluses, who the organizations serve, how they are treated in tax laws, what values they embody, how they are governed, what their legal status is, how extensively they rely on volunteers, or what their objectives are (Salamon and Anheier 1997a, b; Salamon 2010; Evers and Laville 2004; Alcock and Kendall 2011; Cohen and Arato 1994; Edwards 2011; Habermas 1989). These conceptualizations also identify this sector using different terms—including civil society sector, nonprofit sector, voluntary sector, charitable sector, third sector and, more recently, social economy, social enterprise and many more (Teasdale 2010).

Underlying these different perspectives is the fact that conceptualization of the third sector is a contested terrain, a battlefield where different and often opposing views vie for ownership of the concept and its ideological, cultural, and political connotations (Chandhoke 2001; Defourny et al. 1999; Fowler 2002). Diverse and often conflicting interest groups—from left-wing social movements to conservative think tanks—claim proprietorship of the third sector concept because of the emotively desirable connotations it evokes, such as public purpose, freedom of association, altruism, civic initiative, spontaneity or informality. Regional pride also figures into the definitional tangle. When scholars in one major project focused on “nonprofit institutions” as the core of the third sector, colleagues in Europe accused it of regional bias and pointed to cooperatives and mutual associations as also appropriate for inclusion, notwithstanding the fact that it was often difficult to distinguish many of these latter institutions from regular profit-distributing corporations. Many popular perceptions of third sector activities appear to share an underlying ideological position that places a premium on individual entrepreneurship and autonomy, and opposes encroachment on that autonomy by state authorities, while others see this sector as a source of citizen empowerment (Howell and Pearce 2001; Seligman 1992). The third sector thus becomes the carrier of a wildly diverse set of ideological values—an expression of individual freedom, a buffer against state power, a vehicle for citizen promotion of progressive policies, a partner of government in the delivery of needed services and a convenient excuse for cutting government budgets.

1.2 A Sector Hidden in Plain Sight

One reflection of this conceptual confusion is the treatment of third sector institutions in the basic international statistical systems, such as the System of National Accounts (SNA), which guides the collection of economic statistics internationally, and the International Labour Organization (ILO) standards for labor force surveys, which guide the collection of data on employment and work. Although considerable data is actually assembled on third sector institutions, such institutions have long been largely invisible in these existing official statistical systems. This is so because the concepts used to organize these statistical data have not, until very recently, recognized even nonprofit institutions, let alone other potential third sector institutions, as a class around which data should be reported. Rather, in the System of National Accounts, these institutions are allocated to the corporations, government or “nonprofit institutions serving households” sectors based on whether they (a) produce goods or services for sale in the market, (b) are controlled by governmentFootnote 1 or (c) are financed wholly or mostly by charitable contributions from households. Since many potential third sector institutions, such as nonprofits, cooperatives, mutuals and social enterprises, do produce goods and services that are often purchased in the market or on government contracts (e.g. health care, education, day care), they get assigned to the corporation’s sector in national economic statistics, where they lose their identity as third sector entities. Other NPIs judged to be “controlled by” government get allocated to the government sector in economic statistics. The only nonprofit institutions that have been visible in these statistics are thus the so-called nonprofit institutions serving households (NPISH), which are not market producers, not controlled by government, and thus either purely voluntary or supported only by charitable gifts. But this turns out to be a very limited slice of third sector institutions.Footnote 2

When it comes to volunteer work, the situation has been even more problematic. Although the System of National Accounts makes provision for inclusion in basic economic statistics of volunteering done through organizations, it values that volunteer work at the actual cost to employers, which, for all practical purposes, is zero. In the case of direct volunteering, that is, volunteering done directly for other individuals or nonfamily households, the value of this volunteering is counted only if it leads to the production of goods that can be valued at the market cost of comparable products. But direct volunteering that produces services is treated as “household production for own use” and is consequently considered to be “outside the production boundary of the economy” and therefore not counted at all. While quite robust labor force surveys are regularly conducted in virtually all countries, they have historically not asked about volunteer work, and the handful of countries that do ask about such work—through labor force or other specialized surveys—have done so using significantly different definitions and questions, making comparisons across countries—and often even over time within countries—almost impossible. Similarly, time-use surveys (TUSs) ask for both kinds of volunteering defined in accord with the SNA conceptualization outlined above. To date, some 65 countries have implemented TUSs. The problem is that results are often reported at such a high aggregation level that volunteering is not visible in the reporting.

1.3 Why Address this Challenge? The Case for Better Conceptualization and Data

To be sure, as some critics have noted, there are certainly risks in having governments, or any other entity, in possession of data on third sector institutions and volunteer effort (Nickel and Eikenberry 2016). But aside from the fact that in most countries much of such data is already in government hands as a by-product of registration, incorporation or taxation requirements, making such data public can also bring important benefits to third sector organizations (TSOs), volunteering and philanthropy. For example, such data can:

-

Boost the credibility of the third sector by demonstrating its considerable scale and activity. As it turns out, that scale and breadth of activity are orders of magnitude greater than is widely recognized, justifying greater attention to this sector and its needs;

-

Expand the political clout of third sector institutions by equipping them to represent themselves more effectively in policy debates, and thereby help them secure additional resources to support their work;

-

Validate the work of third sector institutions and volunteers, thereby attracting more qualified personnel, expanded contributions and more committed volunteers;

-

Enhance the legitimacy of the third sector in the eyes of citizens, the business community and government;

-

Deepen sector consciousness and cooperation by making the whole of the sector visible to its practitioners and stakeholders for the first time; and

-

Facilitate the ability of the third sector to lay claim to a meaningful role in the design and implementation of policies of particular concern to it, including those involved in the implementation of the recently adopted UN Sustainable Development Goals and embodied in the UN’s 2030 Development Agenda.

At the end of the day, the old aphorism that “what isn’t counted doesn’t count” seems to hold. At the very least, other industries and sectors act in ways that seem to confirm the truth of this aphorism. They are therefore zealous in their demand for reliable data about their economic and other impacts. When existing official data sources fail to provide this, they mobilize to insist on it. This was the recent experience, for example, with the tourism industry, which, like the third sector, finds its various components—airlines, cruise ships, hotels, theme parks, national parks, restaurants and many more—split apart among sectors and industries in existing statistical systems, making them invisible in toto. To correct this, the tourism industry mobilized itself to pressure the official overseers of the System of National Accounts to produce a special handbook calling for the creation of regular Tourism Satellite Accounts by national statistical agencies and then mustered financial support to encourage the implementation of this handbook in countries around the world, precisely the objective that has already been successfully pursued for the nonprofit institution component of the third sector, and now, through the present report, is being proposed for a broader “third or social economy” sector, the TSE sector for short, embracing not only nonprofit institutions, but also social economy, social enterprise and civil society and volunteering elements.

2 Overcoming the Challenges: The Approach

To overcome the challenges in the way of formulating a meaningful conceptualization of the third sector and thereby allow this sector to secure the benefits that this can produce, we utilized a five-part strategy.

2.1 Establishing the Criteria for an Acceptable Conceptualization

As a first step in this process, decisions had to be made about the type of definition at which the conceptualization work was aiming. This was necessary because different types of definitions may be suitable for different purposes. In our case, the hope was that we could formulate a definition capable of supporting empirical measurement of the sector so defined. This meant that a basic philosophical conceptualization would not suffice. Rather, we needed one that could identify operational proxies that could translate the philosophical concepts into observable, operational terms capable of being verified in concrete reality. This led us to five key criteria that our target conceptualization had to embody:

-

Sufficient breadth and sensitivity to encompass as much of the enormous diversity of this sector and of its regional manifestations as possible, initially in Europe, but ultimately globally.

-

Sufficient clarity to differentiate third sector entities and activities from five other societal components or activities widely acknowledged to lie outside the third sector: (a) government agencies, (b) private for-profit businesses, (c) families or tribes, (d) household work and (e) leisure activities. Defining features or legal categories that embraced entities or activities with too close an overlap with these other components or activities thus had to be avoided.

-

Comparability, to highlight similarities and differences among countries and regions. This meant adopting a definition that could be applied in the broadest possible array of countries and regions. This is a fundamental precept of comparative work. The alternative would be equivalent to using different-sized measuring rods to measure tall people and short people so that everyone would come out seeming to be the same basic height.

-

Operationalizability, to permit meaningful and objective empirical measurement and avoid counterproductive tautologies or concepts that involved subjective judgments rather than objectively observable, operational characteristics. Although underlying conceptual or philosophical concepts would be needed to characterize the in-scope components, operational proxies for them would have to be found in order to facilitate actual identification and measurement

-

Institutionalizability, to facilitate incorporation of the measurement of the third sector into official national statistical systems so that reliable data on this sector can be generated on a regular basis as is done with other major components of societal life.

2.2 The Concept of a “Common Core”

In order to adhere to the comparability criterion, the project had to settle on a conceptualization that could be applied in a broad range of countries, including the Global South and not only the industrialized North. To achieve such comparability in the face of the great diversity of concepts and underlying realities, the work outlined here set as its goal not the articulation of an all-encompassing “definition,” but rather the identification of the broadest possible “common core” of the third sector. Central to the concept of a “common core” is the notion that particular countries may have elements in their conceptions of the third sector that extend beyond the common core. This makes it possible to identify a workable common conceptualization of the third sector without displacing other local or regional concepts around which research, data-gathering, policy development and other notions can be organized. Countries or regions can thus use the common core for cross-national comparative purposes and still report on a broader concept in country reports, so long as care is taken to label the different versions appropriately.

2.3 Retention of Component Identities

Consistent with the concept of a modular approach centered on a common-core conceptualization of the third sector is the need to preserve the component identities of the types of institutions and behaviors ultimately identified as belonging to the third sector. This approach opens the door to documenting the significant variations in the composition of the third sector in different locales and avoids lumping quite different collections of institutions and behaviors together in one misleadingly undifferentiated conglomeration.

2.4 Building on Existing Progress

Fortunately, our work was not completely “at sea” in setting out to conceptualize the third sector. Some important progress had already been made in clearly differentiating one set of likely third sector institutions—that is, associations, foundations and other nonprofit institutions (NPIs)—and one broad set of likely third sector individual activities—that is, volunteer work—in the official international statistical system.

2.4.1 Institutional Components

So far as the first is concerned, the United Nations Statistics Division in 2003 issued a Handbook on Nonprofit Institutions in the System of National Accounts (UNSD 2003) that incorporated an operational definition of NPIs into the guidance system for international economic statistics and called on statistical agencies to produce so-called satellite accounts that would better portray this one important potential component of the third sector in official national economic statistics. According to this UN NPI Handbook, such nonprofit institutions could be identified and differentiated from other societal actors on the basis of five defining structural or operational features. In particular, they were:

-

Organizations, that is, formal or informal entities with some meaningful degree of structure and permanence, whether legally constituted and registered or not;

-

Nonprofit-distributing, that is, governed by binding arrangements prohibiting distribution of any surplus, or profit, generated to their stakeholders or investors;

-

Self-governing, that is, able to control their own general policies and transactions;

-

Private, that is, institutionally separate from government and therefore able to cease operations on their own authority; and

-

Noncompulsory, that is, involving some meaningful degree of uncoerced individual consent to participate in their activities.

2.4.2 Individual-Action Component

Likewise, the International Labour Organization, in 2011, issued a Manual on the Measurement of Volunteer Work (International Labour Organization 2011) that established an internationally sanctioned definition of this form of work, which is one form of individual activity widely considered to be a component of the third sector. Specifically, volunteer work is defined as “unpaid non-compulsory work; that is, time individuals give without pay to activities performed either through an organization or directly for others outside their own family.”Footnote 3

The institutional units and activities identified by both definitions are clearly separated from for-profit businesses, government agencies and household activities. These definitions thus served as useful starting points from which to set out on a search for defining elements of a broader third sector concept. This search began in Europe because of research findings in that region suggesting that these initial components were not sufficient to embrace the full common core of the third sector concept in this vast and diverse region, but attention was paid to other possible components in other parts of the world as well.

2.5 A Bottom-up Strategy

Finally, to build a common-core, consensus conceptualization of the third sector broad enough to encompass all relevant types of institutions and behaviors in-scope of this sector, yet operational and clear enough to distinguish in-scope entities from ones that bear stronger resemblance to the other sectors, we devised a bottom-up strategy carried out as part of the larger FP7/TSI research project aimed at defining and measuring the third sector in Europe. With the aid of the research partners in this larger project and an agreed-upon research protocol, we reviewed existing literature and conducted interviews to identify national and regional conceptualizations of the third sector and its component parts in five sets of European regions,Footnote 4 assessed them against a potential consensus definition of the third sector flowing out of broader work and literature, and then analyzed the resulting observations to find whether common understandings could be discerned in these conceptualizations and manifestations.

This methodological approach was carried out in a collaborative and consultative manner allowing the project’s partners to present and discuss their unique regional perspectives and concerns at every stage of the investigation, and working to reconcile them with the overarching objective of developing a consensus conceptualization of the third sector that could be effectively applied both to the different regions of Europe, and more generally as well. Every proposed conceptual component was thoroughly reviewed by all project partners and tested against both the agreed criteria and the known realities on the ground. The results were then reviewed in a series of practitioner workshops and academic seminars, which served to help refine wording and clarify concepts. The upshot was a broad consensus on key features of the resulting conceptualization and operational features.

3 Key Findings and Implications

Two major conclusions flowed from this bottom-up review process.

3.1 Enormous Diversity

In the first place, this review confirmed the initial impressions of enormous diversity in the way the term “third sector” is used, and in the range of organizational and individual activity it could be conceived to embrace even within Europe, let alone in the world at large. Indeed, the range of variation was quite striking.

At one end of the spectrum is the UK, which holds to the concept of “public charities,” as recently articulated in the Charities Act of 2011, but with its real roots in the Elizabethan Poor Law of 1601. This concept is rather narrow and, though broadened a bit in recent legislation and policy debate, remains confined to a historically evolved concept of charity (Kendall and Thomas 1996; Alcock and Kendall 2011; Garton 2009; Six 6 and Leat 1997). To be seen as having charitable purposes in law, the objects specified in organizations’ governing instruments must relate to a list of 12 particular purposes specified in the Charities Act of 2011, and be demonstrably for the public benefit. Not all nonprofit organizations (NPO) are considered charities in the UK, though broader concepts such as “third sector,” “civil society,” “voluntary and community sector,” “volunteering” and “social economy” are sometimes used for policy purposes, but have no legal basis and no clear definitions (UK Office of the Third Sector 2006). The term “social economy” was not widely recognized in the UK until the 1990s (Amin et al. 2002) and is not widely used. In recent years, a robust “social enterprise” sub-sector has emerged, consisting of entities that use market-type activities to serve social purposes, but these take a variety of legal forms. In short, there is no commonly accepted concept of a third sector in the UK, and the plethora of terms and concepts in use raises questions about whether a coherent conceptualization of the third sector is possible, even in a single country, let alone across national borders. At the very least, different definitions may be appropriate for different purposes.

By contrast, in France and Belgium—as well as throughout Southern Europe (Portugal, Spain, Italy and Greece) and in parts of Eastern Europe, the Francophone part of Canada, and throughout Latin America—the concept of “social economy” has gained widespread attention.Footnote 5 In contrast to conceptions prevailing elsewhere in Europe—which underscore organizational features like charitable purpose, volunteer involvement or a nonprofit distribution constraint—the social economy conception focuses on social features, such as the expression of social solidarity and democratic internal governance. In its broad formulations, the concept of social economy embraces not only the voluntary, charitable, or nonprofit sectors, but also cooperatives and mutuals that produce for the market, and newly created “social cooperatives” that are even more clearly socially oriented.Footnote 6 Since many cooperatives and mutuals have grown into enormous commercial institutions, the social economy concept thus blurs the line between market-based, for-profit entities and the nonprofit—or nonprofit-distributing—entities that are central to many northern European and Anglo-Saxon conceptions of what forms the heart of the third sector.

Yet another conception of what constitutes the third sector can be found in Central and Eastern Europe, where the broad overarching concept of “civil society” is widely used in public discourse. Civil society consists of formal organizations and informal community-based structures as well as individual actions taken for the benefit of other people, including improvement of the community or natural environment, participation in elections or demonstrations, informal or direct volunteering and general political participation.Footnote 7 More narrow terms—third sector or nonprofit sector—are used to denote the set of organizations with different legal forms, including associations, foundations, cooperatives, mutual companies, labor unions, business associations, professional associations and religious organizations. The use of various terms changed during the political transformation following the dissolution of the Soviet bloc. The term “nonprofit sector” was very popular in the beginning of the transformation. However, accession to the EU introduced the concept of social economy in this region as well. Recently, the very broad and inclusive term “third sector” has been gaining popularity. It includes all kinds of civil society activities that have permanent or formal structure, including cooperatives and mutuals that allow profit distribution.

Other countries fall on a spectrum among these various alternatives. Some countries hew close to the “British” end of the spectrum, focusing on structured organizations that adhere to a nondistribution of profit constraint. This is the case, for example, in Germany and Austria, where the term “nonprofit organization (NPO)” is common, though the concept of “civil society” has also gained some traction in these countries. However, the values expressed by various actors in this latter sphere are frequently contested (Chambers and Kopstein 2001; Heins 2002; Teune 2008). And this term does not normally extend to the service-providing NPOs mentioned above. The boundaries between civil society and the NPO sector are often blurred, and “civil society,” “third sector” and “NPO sector” are often used synonymously (Simsa 2013), while research under the title of civil society is frequently limited to references to NPOs. In recent years, the term “social entrepreneurs” has gained importance—meaning innovative approaches to mainly social problems, with high market orientation, not necessarily nonprofit, not necessarily involving voluntary elements, and where financial gains can be at least as important as social mission. Cooperatives and mutuals, because they can distribute profit, would not be included in the concept of a third sector in Austria or Germany, though these institutions do exist as parts of the commercial sector. In the Netherlands as well there is also no single overarching concept of the third sector, but three mid-range conceptualizations—particulier initiatief (private initiatives); maatschappelijk middenveld (societal midfield); and maatschappelijk ondernemerschap (social entrepreneurship)—are used instead. These correspond roughly to nonprofit associations providing various services, advocacy groups and social ventures.

Likewise, there is no a single overarching concept of the third sector in the Nordic countries. Instead, different historically evolved types of institutions are commonly identified—voluntary associations, ideal organizations, idea-based organizations, self-owning institutions, foundations, social enterprises, cooperatives, mutual insurance companies and banks and housing cooperatives. Some of these have a legal basis while others do not. For-profit producer, sales or purchasing cooperatives, consumer cooperatives and housing cooperatives have important roles in certain markets in Scandinavia. Cooperatives in the Nordic countries typically distribute profit at a fixed rate according to each member’s stake. The cooperative form expanded in the inter-war period in an attempt to reduce the economic crisis, but Norway did not establish a law on cooperatives until 2008. Sweden has a category of “economic associations” (ekonomiska föreningar) and has recently developed the cooperative form in areas where the government until recently has been the main supplier. However, “social economy” is not widely used and most cooperatives are viewed as profit-distributing institutions. The Nordic countries stand out, however, with respect to the emphasis they place on volunteer work in culture, sports and recreation.

One other institutional element identified in several countries as potential components of the third sector are so-called social enterprises. As noted, these are enterprises that use market mechanisms to serve social purposes. Examples include catering firms that sell their products on the market but choose to employ mostly disadvantaged workers (e.g. persons with previous drug habits or arrest records), using the business to help rehabilitate these workers and prepare them for full-time employment (Nicholls 2006; Bornstein 2004). Special legal forms, such as “Community Interest Companies” in the UK and “Benefit Corporations,” or “B-Corps” in the USA, have been created for such enterprises in some countries, but not all such enterprises have chosen to seek such legal status, preferring to organize under laws that apply to NPOs or to organize as regular for-profit businesses (Lane 2011; and cicassociation.org.uk/about/what-is-a-cic).

3.2 Considerable Underlying Consensus

Despite the considerable disparities in conceptualizations of the social space connoted by the concept of a “third sector” even in this continent, it is good to remember that the third sector is not the only societal sector that has faced the challenge of dealing with diversity in finding a suitable conceptualization of itself. Certainly, the business sector has every bit as much diversity as the third sector, with multiple legal structures, radically different lines of activity, gross variations in scale, complex interactions with government funding and regulatory regimes and widely divergent tax treatments. Yet, scholars, policymakers and statisticians have found reasonable ways to conceptualize this complex array of institutions and distinguish it from other societal components, and popular usage has bought into this formulation.

And fortunately, as it turns out, a somewhat surprising degree of consensus also surfaced in the responses to our field guide search for clarification of the elusive concept of the third sector in its European manifestations, and it seems possible to imagine this consensus applying more broadly as well. The discussion below outlines four important components of this consensus.

3.2.1 Wide Agreement on Three Underlying Common Conceptual Features

Most importantly, while there was disagreement about the precise institutions or behaviors that the concept of the third sector might embrace, the review surfaced a considerable degree of consensus about some of the underlying ideas that the concept of a third sector evoked in Europe (and very likely beyond it). Three of these can be easily identified. They connect the third sector concept, by whatever term used for it, to three key underlying ideas:

-

1.

Privateness—that is, forms of individual or collective action that are outside the sphere or control of government;

-

2.

Public purpose—that is, undertaken primarily to create public goods, something of value primarily to the broader community or to persons other than oneself or one’s family, and not primarily for financial gain; exhibiting some element of solidarity with others; and

-

3.

Free choice—that is, pursued without compulsion.

3.2.2 NPIs are in

Second, there was general agreement that whatever else it embraces, the concept of the third sector certainly embraces the set of institutions defined in the United Nations Handbook on Nonprofit Institutions in the System of National Accounts as NPIs, or nonprofit institutions. As spelled out in that NPI Handbook, these are institutions or organizations, whether formally or legally constituted or not, that are private and not controlled by government, self-governing, nonprofit-distributing (viewed as a proxy for public purpose), and engaging people without compulsion. The defining elements of this component of the third sector have been tested already in more than 40 countries and incorporated into the latest (2008) edition of the methodological guidelines for the official System of National Accounts that guides the work of statistical agencies across the world. Several partners in the TSI Project reverted to this basic set of institutions in defining the core of the third sector concept.

3.2.3 More than NPIs: Cooperatives and Mutuals

While there was widespread agreement that nonprofit institutions are appropriately considered part of the “common core” of the third sector concept, there was also considerable agreement that they could not be considered to constitute the whole of it.Footnote 8 Rather, other types of institutions also needed to be considered. Most obvious were the cooperatives and mutuals that form the heart of the social economy conception so prominent in Southern Europe, but that are present in other parts of the continent and in other regions as well.

The problem here, however, was that some types of cooperatives and mutuals have grown to the point where they are hard to distinguish operationally from for-profit businesses, particularly if some type of limitation on the distribution of profit is taken as a proxy for the pursuit of public purpose, as suggested above and as used effectively in the identification of in-scope NPIs. This applies particularly to such organizations operating in the insurance and financial industries, but extends to some production cooperatives as well. Because of this, there was considerable resistance to embracing all cooperatives and mutuals within the common core concept of the TSE sector in Europe. What is more, there is little sign that it would be possible to convince statistical authorities to include these heavily commercial cooperatives and mutuals as parts of a construct eligible for being carved out of the corporations sector and incorporated into a TSE, satellite account.

3.2.4 More than NPIs: Social Enterprises

A similar situation surrounds the relatively recent concept of “social enterprises.” This type of enterprise that mixes social purpose with market methods has recently gained considerable prominence in a number of European countries, such as the UK, France and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, as well as in parts of Latin America, Asia and Africa. More even than cooperatives and mutuals, however, these entities raise difficult definitional challenges since they seek market returns and are often organized under laws that apply equally to for-profit businesses. In some countries, such as the UK, to be sure, special legal categories have been established for such entities to acknowledge their mixture of social and commercial objectives and activities, as noted earlier. In Italy, for example, a special class of “social cooperatives” has been established for enterprises that operate market production facilities but are required to employ a minimum of 30 percent of their workers from among persons who exhibit one of a list of legally defined forms of disadvantage. In other countries, as well, the cooperative form is also used for such enterprises while elsewhere they organize as NPOs.

There was general agreement that at least some cooperatives, mutuals and social enterprises belong within a concept of a TSE sector. But the fundamental problem facing the inclusion of these entities is the question of how to differentiate the units that should be properly included from those that ought to be excluded due to the fact that they are in fact fundamentally functioning like for-profit businesses and therefore legitimately considered part of the corporations sector in national accounts statistics. This required us to translate the concept of “public purpose” into operational terms that could perform this differentiation function and thus yield a consensus operational definition of the TSE sector amalgam that is consistent with our philosophical principles.

3.2.5 More than Institutions: The Individual Component

The prominence of two other key concepts within the body of thought associated with the “third sector” in Europe made it clear that confining the concept of the third sector to any particular set of institutions would not do full justice to the TSE sector concept in Europe (or elsewhere): (a) first, the concept of “civil society”—with its emphasis on individual citizen action, involvement in social movements, and the so-called public sphere, especially in Central and Eastern Europe; and (b) second, the emphasis on voluntarism as an important component of the third sector concept in the Nordic countries, the UK, and Italy. Accordingly, it was important to include individual activities of citizens within our conceptualization of the third sector. But clearly not all citizen actions could be included. Here, again, distinctions were needed to differentiate activities citizens engage in for their own enjoyment or as part of their family life from those carried out on behalf of others.

The task here was greatly simplified, however, by the existence of the International Labour Organization Manual on the Measurement of Volunteer Work, which offered an operational definition of volunteer work that includes many of the activities that could easily be interpreted as manifestations of civil society, including participation in demonstrations, other forms of political action, as well as other activities undertaken without pay for the benefit of one’s community, or other persons beyond one’s household or family.

3.2.6 Conclusion: Portraying the Third Sector Conceptually

Four more-or-less distinct clusters of entities or activities thus emerged from our bottom-up review process as potential candidates for inclusion within our consensus conceptualization of the third sector in whole or in part: (i) NPOs, (ii) mutuals and cooperatives, (iii) social enterprises and (iv) human actions, such as volunteering and participation in demonstrations and social movements that are undertaken without pay.Footnote 9

However, not all of the entities in each of these clusters seem appropriate to include within a concept of the third sector. This is so because many of them too significantly overlap with other institutional sectors, that is, government, for-profit businesses and household activities—from which the third sector must be distinguished in order to stay true to our basic philosophical conception of a set of institutions or activities that are private, primarily public serving in purpose, and engaging people without compulsion. This bottom-up review thus made it clear that formulating a consensus definition of the third sector required finding a way to differentiate those elements of these institutional and individual components that are “in-scope” of our proposed TSE sector from those that are “out-of-scope” by virtue of being much closer to for-profit businesses, government agencies or household activities.

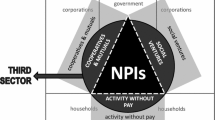

Figure 2.1 provides a pictorial representation of the conceptualization task that the project thus faced. The circular line marks the hypothesized boundary of what we can term the TSE sector, and differentiates the institutional and individual-action components that are in-scope of this sector from those that are out-of-scope. Several features of our conceptualization task stand out starkly in this figure:

-

First, the triangle in the middle represents the nonprofit institution set of entities that forms the core of the TSE sector. The centrality of this set of institutions to the TSE sector concept reflects the fact that the total prohibition on the distribution of profits under which these organizations operate in most European countries, coupled with their noncompulsory character, provides an exceptionally clear operational guide to the fact that these organizations embody the “public purpose” feature considered so central to the TSE sector concept. The central notion here is that a set of institutions in which individuals participate of their own free will without expectation of receipt of any distribution of profit must be perceived by them as serving an important public purpose. This roots the public purpose criterion in the actual behavior of a country’s people rather than being imposed from outside. Except for a relative handful of NPIs created by governments and fundamentally controlled by them, almost the entire class of NPIs consequently falls within the scope of this TSE sector, and the defining features of in-scope NPIs could thus serve as the starting point for building our “consensus definition” of the TSE sector.

-

Also notable in Figure 2.1 are the dotted lines separating NPIs from cooperatives, mutuals, social enterprises and activity without pay. These are intended to reflect the fact that some cooperatives, mutuals and social enterprises are also NPIs, and that some volunteer work takes place within NPIs.

-

Thirdly, the conceptual map also makes clear that the TSE sector is quite broad, potentially embracing cooperatives, mutuals, social enterprises and volunteer work in addition to the many types of NPIs. It does so, however, in modular fashion, separately identifying the different types of entities rather them merging them into one undifferentiated mass, thereby making it possible for particular stakeholders to gain insight into their particular types of organizations and making clear some of the bases for variation in the size and structure of the TSE sector in different regions.

-

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the figure graphically illustrates the significant conceptual and definitional work that still remains, since not all cooperatives, mutuals, social enterprises or individual activity can be considered in-scope of the TSE sector. This is so, as noted earlier, because they do not all embody the philosophical notions that underlie the common understanding of what truly constitutes the TSE sector. The task that remained, therefore, was to identify a set of operational features that could be used to differentiate the in-scope cooperatives, mutuals, and social enterprises from those that are out-of-scope. It is to our approach for completing this task that we therefore now turn.

4 Toward a Consensus Operational Conception of the TSE Sector

To carry out this task, we began with the existing consensus definitions of the NPI sector and volunteer work, respectively, and searched for ways to refine them to incorporate portions of these other potentially in-scope institutional and individual-action components while still adhering to the criteria of breadth, comparability, operationalizability and institutionalizability that we had set for ourselves at the outset. The resulting process was iterative, which means that it consisted of a series of rounds in which partners were asked to provide their input on a set of proposed operational characteristics, on the basis of which the defining features were modified or tweaked and submitted for additional review.

Two sets of hypothesized operational features emerged from this iterative review process: one for institutional units and one for individual human actions. The discussion below outlines these two sets of features separately and indicates how they came to be operationalized. Taken together, the result is a consensus operational definition of the TSE sector that rests on the firm ground of a bottom-up investigative process focusing on actually existing conceptualizations and manifestations of the third sector concept in many different European countries and regions, and that seems likely to work as well in other regions of the world.

4.1 Institutional Components

Following the strategy outlined above, we started our search for in-scope operational features of the institutional components of the TSE sector from the definition of the NPI sector already worked out and incorporated into the United Nations’ Handbook on Nonprofit Institutions in the System of National Accounts (2003) and subsequently integrated into the 2008 revision of the core System of National Accounts. This was possible, in part, because NPIs, at least those not controlled by government, have features that serve as useful embodiments of all three of the crucial philosophical notions central to the third sector concept—privateness, public purpose and uncoerced participation.

The first and third of these were reflected in the definitional requirement that in-scope NPIs be self-governing entities that individuals are free to join or not join voluntarily, and that are private, that is, institutionally separate from government, and not controlled by government, even though they may receive substantial financial support from government. The second was reflected in the fact that nonprofits are prohibited by law or custom from distributing any profits they may earn to their investors, directors or other stakeholders, and must operate under a “capital lock” that stipulates that any assets they accumulate must be dedicated to another nonprofit entity in the same or similar field in the event they cease operation or undergo a transformation into a for-profit entity. Along with the noncompulsory feature, this prohibition on the distribution of profit serves as a convenient and workable proxy for the notion of public purpose.Footnote 10

With this as a starting point, it was an easy jump to realize, based on the input from our bottom-up investigation, that the other potential in-scope institutional components of the TSE sector could be identified by relaxing just one of the key operational features of in-scope NPIs: the feature requiring complete limitation on the distribution of organizational profits to directors or other stakeholders. This is the case because virtually all organizations primarily engaged in the production of public goods or public benefits of any kind, one of the defining features of true TSE sector entities, willingly accept some limitation on their pursuit of profit in order to stay true to their public-purpose mission. Many such organizations provide their goods or services at reduced cost or free of charge. Others engage individuals with disabilities or other barriers to employment, which can affect their productivity and increase costs. Still other organizations cross-subsidize certain members or participants based on their need rather than their ability to pay for goods or services because serving these individuals, rather than maximizing profits, is central to their missions. All such practices significantly limit the ability of these organizations to generate and distribute profits. Relaxing the nonprofit distribution constraint to include organizations that can distribute some surpluses generated by their activities, but by law or custom are “significantly limited” in the extent of this distribution, can thus provide a suitable proxy for the concept of public purpose that is central to our philosophical concept of the third sector and hence offers the operational basis for differentiation between in-scope and out-of-scope cooperatives, mutuals, and social enterprises that we are seeking.

Still needed, however, was a further clarification of what it means to be “significantly limited” in the distribution of profits. For this, it was necessary to examine existing practice in a wide range of countries, from which a number of more specific and concrete specifications were derived.

Out of this set of considerations emerged a consensus definition of the institutional components of the third sector that focuses on five defining features, each of which is translated into operational terms. An institutional unit—whether a NPO, an association, a cooperative, a mutual, a social enterprise or any other type of institutional entity in a country—must meet all five of these features to be considered “in-scope” of the third, or TSE, sector.

In particular, to be considered part of the TSE sector, entities must be:

-

Organizations, whether formal or informal;

-

Private

-

Self-governed;

-

Noncompulsory; and

-

Totally or significantly limited from distributing any surplus they earn to investors, members or other stakeholders.

More specifically, each of these features was translated into operational terms as follows.

4.1.1 The Organization Feature

Organization means that the unit has some institutional reality. To be considered an organization, a unit need not be legally registered. What is important is that it possesses a meaningful degree of permanence, an internal organizational structure, and meaningful organizational boundaries. Informal organizations that lack explicit legal standing but involve groups of people who interact according to some understood procedures and pursue one or more common purposes for a meaningfully extended period (e.g. longer than several months) are included. Groupings that lack even these minimum features of permanence and understood operating procedures (e.g. ad hoc social movements or protest actions) can still be considered parts of the third sector under the individual-action component of the TSE sector discussed below.

4.1.2 The Private Feature

To be considered private, the organization must not be controlled by government. The emphasis here is not on whether the organization receives its income from government, even when this income is substantial; nor does it depend on whether the organization was originally established by a government unit or exercises government-like authority (e.g. issuing licenses to practice particular professions). The ultimate test of not being controlled by government is the ability of the organization’s governing body to dissolve the organization on its own authority. This attribute distinguishes TSE organizations from businesses and nonmarket NPIs that are controlled by government units.Footnote 11

4.1.3 The Self-governing Feature

To be self-governing, the organization must bear full responsibility for the economic risks and rewards of its operations. The need for this defining feature arises from the interconnectedness of various institutional units through legal ownership. Following SNA procedures, we distinguish between legal and economic ownership and put the emphasis on the latter rather than the former. While a TSE organization may be created by a corporation, it is not considered to be controlled by that corporation so long as it retains full responsibility for the economic risks and rewards entailed in its operations. Entities that assume the economic risks and rewards for their operations are “self-governed” and thus institutionally separate from other units that may legally own them. Such self-governed units are allocated to economic sectors based on their own economic activities rather than those of the units that may legally own them. Thus, a for-profit business that is fully responsible for the economic risks and rewards of its operations is not in-scope of the TSE sector even though it is legally owned by a unit that is in-scope. Likewise, a TSE unit that is fully responsible for its economic and risks and rewards is still treated as in-scope of the TSE sector satellite account, even if it is legally “owned” by a for-profit corporation.

4.1.4 The Noncompulsory Feature

To be considered noncompulsory, participation with the organization must be free of compulsion or coercion, that is, it must involve a meaningful degree of choice. Organizations in which participation is dictated by birth (e.g. tribes, families, castes), legally mandated or otherwise coerced, such as community service volunteering required to meet a court penalty or fulfill a military obligation, are excluded. Organizations in which membership is required in order to practice a trade or profession, or operate a business, can be in-scope so long as the choice of profession or business is itself a matter of choice.

This feature, combined with the limited profit-distribution requirement outlined below, serves as a proxy for a public-interest purpose, since organizations in which individuals freely choose to participate, but from which they can expect to secure only limited profit or none at all, must be organizations that serve some public purpose in the minds of those who are involved with them.

4.1.5 The Totally or Significantly Limited Profit-distribution Feature

To meet this condition, organizations must be prohibited, either by law, internal governing rules, or by socially recognized customFootnote 12 from distributing either all or a significant share of the profits or surpluses generated by their productive activities to their directors, employees, members, investors or others. This attribute distinguishes TSE sector organizations from corporations, which permit the distribution of surpluses generated to their owners or shareholders. TSE organizations may accumulate surplus in a given year, but that surplus or its significant share must be saved or plowed back into the basic mission of the agency and not distributed to the organizations’ directors, members, founders or governing board. In this sense, TSE organizations may be profitmaking but unlike other businesses they are nonprofit-distributing, either entirely or to a significant degree.

This condition embraces the full nondistribution-of-profit feature used to define “nonprofit institutions,” but broadens it to embrace organizations that permit some distribution of profit (e.g. cooperatives, mutuals and social enterprises), but still restricts it to those of these entities that are required by law or custom to place some significant limit on such distribution. While the prohibition on distribution of any profit is self-explanatory, the determination that an organization has a significant limitation on profit distribution is based on the following four indicators, as shown in Fig. 2.2 and elaborated more fully below:

-

4.1.5(a) Public-purpose mission. To be considered in-scope of the TSE sector, an organization must be bound by law, articles of incorporation, other governing documents or settled custom to the pursuit of a social purpose. What constitutes a public or social purpose may vary widely among countries and over time, but the central concept is that the organization is legally committed to a mission that prioritizes the production of public goods or other social or environmental benefits of value to broadly defined communities over the maximization of profit. Various attempts have been made to characterize the concept of public purpose with special terms, such as “charitable” or “in the public interest,” but these carry different meanings in different places and eras. Core concerns revolve around concepts of health, welfare, education, public safety, human and civil rights, overcoming inequalities, promoting employment, protecting human and civil rights and pursuing justice. The key, though, is to free organizations from the requirement to pursue profit maximization over the commitment to improving human or animal welfare, the environment or social solidarity.

-

4.1.5(b) Significant and binding limitation on distribution of profits. Important as a clear commitment to a public purpose is to the identification of organizations in-scope of the TSE sector, because of the diffuseness of conceptions of “public purpose,” this is at best a “necessary” but “not a sufficient” determinant of public-purpose activity. In the case of NPIs, this is achieved through the prohibition on distributing any profits, but since cooperatives, mutual societies and social enterprises are permitted to distribute some of the surpluses generated by their activities, a suitable alternative is to require some “significant” limitation on their profit distribution as a comparable tangible indicator of their meaningful pursuit of public purpose. The key test is that the limitation must be sufficient to differentiate in-scope entities clearly from for-profit firms. What that standard should be may be taken from the international consensus that appears to be emerging with respect to social enterprises, institutions that are even more like for-profit corporations than are cooperatives and mutual. Several recent European laws thus stipulate that to be considered true “social enterprises,” organizations must dedicate to the organization’s social mission, and therefore not distribute, at least 50 percent of any profits they might earn. This standard might appropriately be applied to cooperatives and social enterprises as well.

In all these cases, however, some adjustment of this specific figure may be appropriate where the valid social mission of the units involves activities that have the effect of reducing the amount of profit earned. This could be the case, for example, where part of the social mission of the organizations is to subsidize the cost of products or services by selling them below market prices to members, or employ substantial numbers of persons suffering from some disability or chronic disadvantage, thus boosting the costs of training and social support. Such subsidies or extra costs could be considered part of the retained earnings in support of the organizations’ social mission.

-

4.1.5(c) Capital lock. In addition to the requirement for a total or significant limitation on the distribution of profit, in-scope TSE units must also operate under laws, explicit governance provisions or, where such formal provisions were not in place when the organization was originally established, set social customs establishing a “lock” on any surplus retained. Such rules prohibit the distribution of the retained surplus and any other assets owned by the organization to its owners, directors or other stakeholders, in the event of the organization’s dissolution, sale or conversion to “for-profit” status. Rather, any such retained surplus or assets must be transferred to another entity set up for a similar social purpose and subject to the same requirements as those in-scope of the TSE sector.

-

4.1.5(d) Prohibition on any distribution of profits in proportion to capital invested or fees paid. This prohibition is one of the defining features of cooperatives and mutual societies that differentiates them from other market producers (e.g. joint stock corporations) that typically distribute surpluses in proportion to invested capital or fees paid. This prohibition does not apply to payment of interest on invested capital so long as the interest does not exceed prevailing market rates or rates on government bonds. The purpose of this indicator is to differentiate cooperatives that primarily serve some social or other public purpose from those primarily seeking returns on invested capital. Prohibition of profit distribution in proprtion to capital invested applies only to coops; social enterprises by definition are not coops within the framework of the UN Handbook.

Each of these requirements is based on existing laws or customs in existence in some European countries, among at least some cooperatives, mutuals or social enterprises, though each may need further refinement once the range of practice is further analyzed. Thus, for example, to be designated as a “social cooperative” in Italy, organizations must maintain a labor force 30 percent of which must be people with certain specified special needs. The prohibition on the distribution of profit on the basis of investment or fees reflects one of the defining features of “social cooperatives” found in a prominent analysis of European cooperatives (Barea and Monzón 2006). And social enterprise laws in Belgium and France set the “no more than 50 percent” standard as the limitation on distribution of profit required for designation as a social enterprise in these countries.

All four of these indicators should be met to qualify as an entity subject to a “significant limitation on profit distribution.” A decision based on the totality of these indicators will necessarily be judgmental in nature as, in some cases, some of these indicators may carry a different relevance and thus weigh differently on the final decision than others.

Summary. Taken together, therefore, this set of operational features meets the criteria we set for an acceptable conceptualization of the third sector that is at once broader than the nonprofit sector, consistent with the consensus philosophical precepts of the third sector concept that emerged from our bottom-up investigation and operationalizable enough to be integrated into existing statistical machinery. In the process, these features make it possible to foster the development of official “satellite accounts” on a TSE sector that is much broader than the one called for in the 2003 UN NPI Handbook, yet sufficiently differentiated from other institutional units to be integrated into national accounts statistical systems and win the support of national accounts officials. Reflecting this, the United Nations Statistics Division, working with one of the present authors, has approved for international review pending submission for final approval at a meeting of the United Nations’ Statistical Commission at its next meeting, a proposed Satellite Account on Nonprofit and Related Institutions and Volunteer Work that embodies this conceptualization

In-scope under this core definition of the TSE sector are thus:

-

1.

Virtually all NPIs as defined in the UN Handbook on Nonprofit Institutions in the System of National Accounts. This includes not only NPISH, but also “market NPIs” assigned to the corporations sectors in the System of National Accounts, so long as they embody the definitional features of NPIs. The only exceptions are those NPIs that are controlled by government (including official state churches) and units nominally registered as NPIs that de facto distribute profits (e.g. in the form of excessive compensation of directors or key stakeholders). Particular types of organizations—for example, hospitals, universities and cultural institutions—may be organized as “third sector” organizations in some countries and as governmental institutions or for-profit institutions in others. Indeed, all three forms of such institutions can exist in particular countries, but this definition makes it possible to determine which of these are truly NPIs and which not. Borderline cases can include political parties (in some countries, they may be controlled by government) and indigenous peoples’ associations (in some countries their membership may be decided by birth or the organizations may exercise governmental authority).

-

2.

Some, but very likely not all, cooperatives and mutuals. Cooperatives that are organized as nonprofits, or social cooperatives that operate under legal requirements stipulating a minimum of at least 30 percent of employees or beneficiaries that exhibit certain “special needs,” would be clearly in-scope. So are other types of cooperatives and mutuals that meet the significantly limited profit-distribution feature. As a general rule, cooperatives and mutuals in northern European countries (such as Belgium, Germany or the Scandinavian countries) tend to lack such clear limitations on their distribution of profits and are therefore likely to be out-of-scope of the TSE sector. By contrast, southern European countries (Bulgaria, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Spain and Portugal) more often impose conditions on cooperatives and mutuals that have the effect of significantly limiting their distribution of profit. These cooperatives are more likely to be in-scope of the TSE sector so long as they meet the operational criteria for limited profit-distribution identified above. By contrast, market-oriented cooperatives that operate as profit-distributing businesses and are free to distribute all profits are out-of-scope. As a general rule, cooperatives and mutuals in the financial services sector, such as banks and mutual insurance companies, would likely be out-of-scope since they have typically evolved into large-scale businesses that are hard to distinguish from regular, profit-seeking companies.

-

3.

Social enterprises that are registered as NPIs, social or mutual activity cooperatives, community benefit corporations in the UK, special B-Corps in the USA or other countries, and entities operating as officially designated social cooperatives or social economy institutions in Belgium or France are likely in-scope of the third sector as identified here. So, too, are enterprises that belong to social enterprise networks that require the pursuit of significant social or environmental benefits. Social enterprises registered as regular corporations are either borderline cases or out-of-scope, as are companies that operate corporate social responsibility programs but otherwise have no significant limitation on their generation or distribution of profits.

Finally, all privately owned for-profit businesses, and all government agencies and units controlled by them, are out of the TSE scope.

4.2 Informal and Individual Components

In addition to organizations, the TSE sector embraces a variety of individual and informal activities. That portion of such activity undertaken to or through organizations is naturally recorded as part of the workforce of the in-scope organizations. Strictly speaking, the additional portion is the portion done directly for individuals or other families. In both cases, however, the task here is to differentiate the in-scope individual activities from normal leisure activities and recreation and from unpaid household activity, such as performing household chores, or helping members of one’s close family.

Fortunately, much of the work of operationalizing this border has already been done and captured in the Manual on the Measurement of Volunteer Work issued by the International Labour Organization in 2011, and subsequently further ratified at the 19th International Conference of Labour Statisticians in 2013. The resulting conceptualization views the individual activity considered in-scope of the TSE sector as a form of unpaid work, thus differentiating it from activity one does for one’s own or one’s family’s enjoyment, edification or quality of life. Under the resulting official, internationally sanctioned definition, volunteer work is thus defined as “unpaid, non-compulsory work; that is, time individuals give without pay to activities performed either through an organization or directly for others outside their own household or family.”

We adopt this recommended definition here as suitable for identifying the individual activity considered in-scope of the TSE sector, with one difference: the TSE sector includes all direct volunteer work but only that organization-based volunteer work done through TSE organizations. Volunteer work carried out through government agencies or for-profit corporations are therefore not in-scope of the TSE sector.

More specifically, individual activities in-scope of the TSE sector as volunteer work under this definition must exhibit the following operational features:

-

They produce benefits for others and not just, or chiefly, for the person performing them. The test here is whether the activity could be replaced by that of a paid substitute. Thus, for example, time spent playing the piano for one’s personal enjoyment would not be considered a TSE sector activity, whereas playing the piano for residents of a nursing home would qualify.

-

They are not casual or episodic. Rather, the activity must be carried on for a meaningful period of time, typically defined as an hour in a certain “reference period.” Helping an elderly person across the street one time would thus not qualify as volunteer work, but serving as the unpaid crossing guard at a school would.

-

They are unpaid. That is, the person performing them is not entitled to any compensation in cash or kind. Although this feature is straightforward and self-explanatory, its application may be problematic in those circumstances where people performing these activities receive something of value that is not formally defined as compensation or wages. This may include token gifts of appreciation, accommodations, reimbursement of expenses or stipends. Under provisions embodied in a new regulation on the measurement of work issued by the ILO, receipt of pay that is less than one-third of the normal pay for a particular job does not disqualify such an activity from being in-scope of the TSE sector.

-

The activity is not aimed at benefiting members of one’s household or their close family or families (e.g. next of kin—brothers, sisters, parents, grandparents and respective children).

-

The activity is noncompulsory, which means it involves a meaningful element of individual choice. To be considered noncompulsory:

-

The person performing the activity must have the capacity to choose whether or not to undertake it.

-

This excludes activities undertaken by minors or the mentally challenged.

-

The person performing the activity must be able to cease performing it at any time if they so choose. If not, the activity is not noncompulsory.

-

Performing the activity is not required by law, governmental decree or other legal obligation.

-

If performing the activity is required to practice a trade, profession or similar economic activity or to complete educational requirements, then there must be a meaningful element of choice in the selection of that trade, profession, economic activity or educational program.

-

Responding to a social norm or religiously inspired sense of personal obligation does not violate this noncompulsory feature.

-

Summary. The human action in-scope of the TSE sector under this definition is quite broad. It includes all uncompensated work performed either directly for people outside of one’s close family or through an in-scope TSE organization to (i) improve a community; (ii) organize public, cultural, or religious events; (iii) promote public health, safety, or education; (iv) provide emergency relief or preparedness; (v) clean up the environment or rescue animals; (vi) help a person in need with food, assistance, or companionship; (vii) take part in, or organize, a demonstration or advocacy campaign; (viii) uncompensated pro-bono work undertaken in a professional capacity (e.g. legal or emotional counseling, review of scientific papers for publication, arbitration, etc.).