Abstract

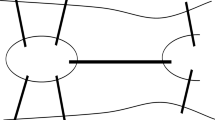

The trends discernible within the history of mathematics display a recurring one-sidedness. With an alternative non-reductionist ontology in mind this contribution commences by challenging the assumed objectivity and neutrality of mathematics. It is questioned by the history of mathematics, for in the latter Fraenkel et al. (Foundations of Set Theory, 2nd rev. ed., Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1973) distinguish three foundational crises: in ancient Greece with the discovery of incommensurability , after the invention of the calculus by Leibniz and Newton (problems entailed in the concept of a limit), and when it turned out that the idea of infinite totalities, employed to resolve the second foundational crisis, suffered from an inconsistent set concept. An alternative approach is to contemplate the persistent theme of discreteness and continuity further while distinguishing between the successive infinite and the at once infinite. Weierstrass, Dedekind, and Cantor define real numbers in terms of the idea of infinite totalities. Frege reverted to a geometrical source of knowledge while rejecting his own initial logicist position. Some theologians hold the view that infinity is a property of God and that theology therefore should mediate its introduction into mathematics. Avoiding the one-sidedness of arithmeticism (over-emphasizing number) and geometricism (over-emphasizing spatial continuity) will require that both the uniqueness of and mutual coherence between number and space is acknowledged. Two figures capture some of the essential features of such an alternative approach. Mediated by a Christian philosophy and a non-reductionist ontology, Christianity may therefore contribute to the inner development of mathematics.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

“Will man zum Schluß ein kurzes Schlagwort, welches den lebendigen Mittelpunkt der Mathematik trifft, so darf man wohl sagen: sie ist die Wissenschaft des Unendlichen ” (Weyl 1966, 89).

- 2.

“Lorsque les valeurs successivement attribuées à une même variable s’approchent indéfiniment d’une valeur fixe, de manière à finir par en différer aussi peu que l’on voudra, cette dernière est. appelée la limite de toutes autres”—quoted in Robinson (1966, 269).

- 3.

In general, a number l is called the limit of the sequence (x n ) when for an arbitrary rational number є > 0 there exists a natural number n 0 such that │x n –l│ < є holds for all n ≥ n 0 (see Heine 1872, 178, 179, and in particular page 184 where a limit is described in slightly different terms). Consider the sequence n/n + 1 where n = 1, 2, 3, … (in other words the sequence 1/2, 2/3, 3/4, …). This sequence converges to the limit 1.

- 4.

“Somit bleibt mir nichts Anderes übrig, als mit Hilfe der in §9 definierten reellen Zahlbegriffe einen möglichst allgemeinen rein arithmetischen Begriff eines Punktkontinuums zu versuchen ” (Cantor 1962, 192).

- 5.

“Die entscheidende Erkenntnis des Aristoteles war, dass Unendlichkeit wie Kontinuität nur in der Potenz existieren, also keine eigentliche Aktualität besitzen und daher stets unvollendet bleiben. Bis auf Georg Cantor , der in der 2. Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts dieser These mit seiner Mengenlehre entgegentrat, in der er aktual unendliche Mannigfaltigkeiten betrachtete, ist die aristotelische Grundkonzeption von Unendlichkeit und Kontinuität das niemals angefochtene Gemeingut aller Mathematiker (wenn auch nicht aller Philosophen) geblieben ” (Becker 1964, 69).

- 6.

“Aus dem Paradies, das Cantor uns geschaffen [hat], soll uns niemand vertreiben können ” (see Hilbert 1925, 170).

- 7.

“In der Arithmetik … liegt kein Motiv zur Einführung von Aktual-Unendlichen vor ” (Lorenzen 1972, 159).

- 8.

Nickel quotes Vern S. Poythress saying: “In exploring mathematics one is exploring the nature of God’s rule over the universe; i.e. one is exploring the nature of God Himself” (see Poythress 1976, 184).

- 9.

See the quotation given in n. 4 above.

- 10.

- 11.

At the young age of 25 Gödel astounded the mathematical world in 1931 by showing that no system of axioms is capable—merely by employing its own axioms—of demonstrating its own consistency (see Gödel 1931). Yourgrau remarks: “Not only was truth not fully representable in a formal theory, consistency, too, could not be formally represented ” (Yourgrau 2005, 68). The devastating effect of Gödel’s proof is strikingly captured in the assessment of Hermann Weyl : “It must have been hard on Hilbert , the axiomatist, to acknowledge that the insight of consistency is rather to be attained by intuitive reasoning which is based on evidence and not on axioms ” (Weyl 1970, 269).

- 12.

Note that Bernays employs the term factual in the sense in which we want to employ it—referring to what is given in reality prior to human cognition.

- 13.

Kattsoff defends a similar view where he discusses “intellectual objects” which are also characterized by him as “quasi-empirical” in nature (Kattsoff 1973, 33, 40).

- 14.

Frege correctly remarks “that counting itself rests on a one-one correlation, namely between the number-words from 1 to n and the objects of the set ” (quoted in Dummett 1995, 144).

- 15.

“Die hier gewonnenen Ergebnisse wird man auch dann würdigen, wenn man nicht der Meinung ist, daß die üblichen Methoden der klassischen Analysis durch andere ersetzt werden sollen. Zuzugeben ist, daß die klassische Begründung der Theorie der reellen Zahlen durch Cantor und Dedekind keine restlose Arithmetisierung bildet. Jedoch, es ist sehr zweifelhaft, ob eine restlose Arithmetisierung der Idee des Kontinuums voll gerecht werden kann. Die Idee des Kontinuums ist, jedenfalls ursprünglich, eine geometrische Idee. Der arithmetisierende Monismus in der Mathematik ist eine willkürliche These. Daß die mathematische Gegenständlichkeit lediglich aus der Zahlenvorstellung erwächst, ist keineswegs erwiesen. Vielmehr lassen sich vermutlich Begriffe wie diejenigen der stetigen Kurve und der Fläche, die ja insbesondere in der Topologie zur Entfaltung kommen, nicht auf die Zahlvorstellungen zurückführen.”

References

Becker, Oscar. 1964. Grundlagen der Mathematik in geschichtlicher Entwicklung. Freiburg: Alber.

Bernays, Paul. 1976. Abhandlungen zur Philosophie der Mathematik. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Beth, Evert. 1965. Mathematical Thought. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Boyer, Carl B. 1959. The History of the Calculus and Its Conceptual Development. New York: Dover.

Brouwer, Luitzen Egbertus Jan. 1964. Consciousness, Philosophy, and Mathematics. In Philosophy of Mathematics, Selected Readings, ed. Paul Benacerraf and Hillary Putnam, 78–84. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Cantor, Georg. 1962. Gesammelte Abhandlungen Mathematischen und Philosophischen Inhalts. Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlagsbuchhandlung.

Chase, Gene B. 1996. How Has Christian Theology Furthered Mathematics? In Facets of Faith and Science, The Role of Beliefs in Mathematics and the Natural Sciences: An Augustinian Perspective, ed. Jitse M. van der Meer, vol. 2, 193–216. New York: University of America Press.

Dooyeweerd, Herman. 1997. A New Critique of Theoretical Thought, The Collected Works of Herman Dooyeweerd, Series A. Vols. 1−4. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press.

Dummett, Michael A.E. 1978. Elements of Intuitionism. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

———. 1995. Philosophy of Mathematics. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Fern, Richard L. 2002. Nature, God and Humanity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fraenkel, Abraham. 1928. Einleitung in die Mengenlehre. 3rd ed. Heidelberg: Springer.

———. 1930. Das Problem des Unendlichen in der neueren Mathematik. Blätter für deutsche Philosophie 4 (1930/31): 279−297.

Fraenkel, Abraham A., Yehoshua Bar-Hillel, and Azriel Levy. 1973. Foundations of Set Theory. With the Collaboration of Dirk van Dalen. 2nd rev. ed. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Frege, Gottlob. 1903. Grundgesetze der Arithmetik. Vol. 2. Jena: Verlag Hermann Pohle.

———. 1979. Posthumous Writings. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Gödel, Kurt. 1931. Über formal unentscheidbare Sätze der Principia Mathematica und verwandter Systeme 1. Monatshefte für Mathematik und Physik 38: 173–198.

Grünbaum, Adolf. 1952. A Consistent Conception of the Extended Linear Continuum as an Aggregate of Unextended Elements. Philosophy of Science 19 (2): 288–306.

Heine, Eduard. 1872. Die Elemente der Functionenlehre. Journal für reine und angewandte Mathematik 74: 172–188.

Hersh, Reuben. 1997. What Is Mathematics Really? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heyting, Arend. 1949. Spanningen in de wiskunde. Groningen/Batavia: P. Noordhoff.

———. 1971. Intuitionism: An Introduction, 3rd rev. ed. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Hilbert, David. 1925. Über das Unendliche. Mathematische Annalen 95: 161–190.

Husserl, Edmund. 1979. Aufsätze und Rezensionen (1890–1910). Husserliana: Edmund Husserl – Gesammelte Werke 22. Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff.

Kattsoff, Louis O. 1973. On the Nature of Mathematical Entities. International Logic Review 7: 29–45.

Kline, Morris. 1980. Mathematics: The Loss of Certainty. New York: Oxford University Press.

Laugwitz, Detlef. 1986. Zahlen und Kontinuum: Eine Einführung in die Infinitesimalmathematik. Mannheim: B.I.-Wissenschaftsverlag.

Longo, Giuseppe. 2001. The Mathematical Continuum: From Intuition to Logic. ftp://ftp.di.ens.fr/pub/users/longo/PhilosophyAndCognition/the-continuum.pdf. Accessed 19 Oct 2010.

Lorenzen, Paul. 1972. Das Aktual-Unendliche in der Mathematik. In Grundlagen der modernen Mathematik, ed. Herbert Meschkowski, 157–165. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Nickel, James D. 2001. Mathematics: Is God Silent? Vallecito: Ross House Books.

Plotinus. 1956. The Enneads, 2nd ed. Trans. Stephen MacKenna, Revised by D.S. Page. London: Faber & Faber.

Poythress, Vern S. 1976. A Biblical View of Mathematics. In Foundations of Christian Scholarship: Essays in the Van Til Perspective, ed. Gary North, 158–188. Vallecito: Ross House Books.

Reidemeister, Kurt. 1949. Das exakte Denken der Griechen. Beiträge zur Deutung von Euklid, Plato und Aristoteles. Hamburg: Reihe Libelli.

Robinson, Abraham. 1966. Non-Standard Analysis. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Stegmüller, Wolfgang. 1970. Main Currents in Contemporary German, British and American Philosophy. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Strauss, Danie. 2011a. Bernays, Dooyeweerd and Gödel – The Remarkable Convergence in Their Reflections on the Foundations of Mathematics. South African Journal of Philosophy 30 (1): 70–94.

———. 2011b. Defining Mathematics. Acta Academica 4: 1–28.

———. 2014. What Is a Line? Axiomathes 24: 181–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10516-013-9224-5.

Wang, Hao. 1988. Reflections on Gödel. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Weyl, Hermann. 1919. Der circulus vitiosus in der heutigen Begründung der Analysis. Jahresberichte der Deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung 28: 85–92.

———. 1946. Mathematics and Logic: A Brief Survey Serving as Preface to a Review of The Philosophy of Bertrand Russell. The American Mathematical Monthly 53: 2–13.

———. 1966. Philosophie der Mathematik und Naturwissenschaft, 3rd rev. and exp. ed. Munich/Vienna: R. Oldenbourg.

———. 1970. David Hilbert and His Mathematical Work. In Hilbert. With an Appreciation of Hilbert’s Mathematical Work by Hermann Weyl, ed. Constance Reid, 243–285. New York: George Allen & Unwin.

Yourgrau, Palle. 2005. A World Without Time. The Forgotten Legacy of Gödel and Einstein. London: Penguin Books.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Strauss, D. (2017). Christianity and Mathematics. In: Glas, G., de Ridder, J. (eds) The Future of Creation Order. New Approaches to the Scientific Study of Religion , vol 3. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70881-2_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70881-2_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-70880-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-70881-2

eBook Packages: Religion and PhilosophyPhilosophy and Religion (R0)