Abstract

The entry of women into the labor market with an active and permanent presence is, today, a subject of a heated debate among scholars and policy makers that sees, on the one hand, diversity in gender relations and women’s employment and on the other hand the economic importance of women and increasing economic efficiency. At international level, greater economic and political role of women is recognized as a sign of economic vitality of the country. The increase in female education rates, the economic and cultural globalization, public policies favorable to families, and recent legislative impositions have enlivened this debate highlighting two crucial aspects: a greater integration of women meeting the equitable principles of equal opportunities and a greater integration of women responding to greater efficiency and economic growth. The main limitations and difficulties in the participation of women in the labor market are numerous and complex and often interconnected: direct discrimination, occupational segregation, stereotypes, conciliation of life and work, the service coverage rates, etc.

In this paper we use World Bank data on fertility rates around the world from 1960 to 2013, and we analyze the different time series related to fertility rates of different countries in order to detect different clusters. The classification of different countries considered in different clusters is performed by considering an appropriate clustering methodology and the dynamic time warping distance. At this point we interpret the different clusters in order to considering also the different labor markets and policies as a relevant determinant of the dynamic of the fertility rate over time and a relevant statistical reason of the formation of the cluster. The aim of this paper is to provide how and if greater attention to women considerations could lead to a greater understanding of the obstacles that prevent the full participation of women in the economy and in particular in the labor market. This recognition allows the creation of more targeted assistance programs to address these obstacles thus creating an environment for even better response from policy makers. This paper is organized as follows. In the first section, we present a recent review of the main literature on women in the labor market. The second section presents data. The third section presents the methodology used and the fourth all different statistical results. In the fifth section, we discuss all results obtained. Finally, we conclude.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ahn, N., & Mira, P. (2001). Job bust baby bust? Evidence from Spain. Journal of Population Economics, 14(3), 505–522.

Becker, G., & Lewis, H. G. (1973a). Interaction between quantity and quality of children. InEconomics of the family: Marriage, children, and human capital. Chicago, IL: Univeristy of Chicago Press.

Becker, G., & Lewis, H. G. (1973b). On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 82, S279–S288.

Becker, G. S. (1960). An economic analysis of fertility. InDemographic and economic change in developed countries. New York City, NY: Columbia University Press. isbn: 0-87014-302-6.

Butz, W. P., & Ward, M. P. (1979a). The emergence of countercyclical U.S. fertility. The American Economic Review, 69(3), 318–328.

Butz, W. P., & Ward, M. P. (1979b). The emergence of countercyclical US fertility American Economic Review, 69(3), 318–328.

Coleman D. (2006). Immigration and Ethnic Change in Low-Fertility Countries: A Third Demographic Transition. Population and Development Review. Vol. 32, No. 3 (Sep., 2006), pp. 401–446.

Del Boca, D. (2002). The effect of child care and part time opportunities on participation and fertility decision in Italy. Journal of Population Economics, 15, 549–573.

Devaney (1983B). An analysis of variation in U.S. fertility and female labor force participation trends. Demography, 20, 147–161.

Dunn, J. (1974). Well separated clusters and optimal fuzzy partitions. Journal of Cybernetics, 4, 95–104.

Engelhardt, H., Kogel, T., & Prskawetz A. (2001a). Fertility and Female Employment reconsidered. MPIDR Working Paper WP 2001-021 Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research.

Engelhardt, H., Kogel, T., & Prskawetz, A. (2001b). Fertility and female employment reconsidered: A macro-level time series analysis. MPIDR Working Paper WP 2001-021, Rostock: Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research. Devaney, 1983; Heckman and Walker, 1990.

EU Report. (2012). The impact of economic crisis on the situation of women and men and on gender equality policies. InSynthesis report. isbn: 978-92-79-28680-3. Brussels: European Commission.

Eurostat (2016). Fertility statisitics. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.phptitle=Fertility_statistics&oldid=282365

Eurostat (2013). Fertility statistics in relation to economy, parity, education and migration”. ISSN:2314-9647

Ferrera, M. (2008). Dal welfare state al welfare regions: la riconfigurazione spaziale della protezione sociale in Europa. In Rivista delle politiche sociali.

Ghererghi, M., & Andlauro, C. (2004). Appunti di analisi dei dati multidimensionali: Metodologia ed esempi. RCE edizioni.

Guinnane T. W. (2011). The Historical Fertility Transition: A Guide for Economists. Journal of Economic Literature. Vol. 49, No. 3, September 2011. (pp. 589–614).

Heckman J., Walker J. (1990). The relationship between wages and income and timing and spacing of births: evidence from Swedish longitudinal data. Econometrics, 58, 1411–1441.

ILO. (2014). The motherhood pay gap: A review of the issues, theory and international evidence. InConditions of work and employment series no. 57. Geneva: ILO.

Klasen, S. (1999). Does gender inequality reduce growth and development? Evidence from cross-country regressions. Policy research report on gender and development working paper series, No. 7.

Leibenstein, H. (1957). Economic Backwardness and Economic Growth, New York: Wiley.

Liao, T. W. (2005). Clustering of time series data—A survey. Pattern Recognition, 38(11), 1857–1874.

Livi, B. M. (2017). Dobbiamo anticipare l’età dell’autonomia per i nostri giovani. In Corriere della Sera.

Lutz, W., Skirbkk, V., & Testa, M. (2005). The Low Fertility trap hypothesis: Forces that may lead to further postponement and fewer births in Europe. In European Demographic Research Papers.

Matsui, K. (2005). Womenonomics: Japan’ s hidden asset. In Goldms Sachs Japanese Portfolio Strategies.

McKinsey Report (2015). The outlook for global growth in 2015.

Morgan, S. P., & Taylor, M. G. (2006). Low fertility at the turn of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Sociology, 32, 375–399. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122220.

OECD (2005). Women and Men in OECD countries.

The Economist. (2006). A guide to womeconomics. The future of the world economy lies increasingly in female hands.

UNAIDS. (2012). Impact of the global economic crisis on women, girls and gender equality. isbn: 978-92-9173-989-9.

United Nations (2010). Human Development Report 2010 20th Anniversary Edition. The Real Wealth of Nations: Pathways to Human Development.

Willis, R. (1973a). A new approach to the economic theory of fertility behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 81(2), S14–S64.

Willis, R. J. (1973b). A new approach to the economic theory of fertility behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 81(2), 3–18.

Wittemberg-Cox, C. A., & Maitlan, A. (2009). Rivoluzione Womenomics. Perchè le donne sono il motore dell’economia, Gruppo 24ore.

World Bank (2015). World Development Report: Mind, Society, and behavior

World Bank (2016) World Development Indicators. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-developmentindicators

World Economic Forum (2015). The Global Gender Gap Report

Zhao, Y., & Cen, Y. (Eds.). (2013). Data mining applications with R. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, Elsevier. isbn: 978-0-12-411511-8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

2.1.1 Nations Considered

-

1.

Afghanistan

-

2.

Albania

-

3.

Algeria

-

4.

Angola

-

5.

Antigua and Barbuda

-

6.

Argentine

-

7.

Armenia

-

8.

Aruba

-

9.

Australia

-

10.

Austria

-

11.

Azerbaijan

-

12.

Bahamas, The

-

13.

Bahrain

-

14.

Bangladesh

-

15.

Barbados

-

16.

Belarus

-

17.

Belgium

-

18.

Belize

-

19.

Benin

-

20.

Bhutan

-

21.

Bolivia

-

22.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

-

23.

Botswana

-

24.

Brazil

-

25.

Brunei Darussalam

-

26.

Bulgaria

-

27.

Burkina Faso

-

28.

Burundi

-

29.

Cabo Verde

-

30.

Cambodia

-

31.

Cameroon

-

32.

Canada

-

33.

Central African Republic

-

34.

Chad

-

35.

Channel Islands

-

36.

Chile

-

37.

Cinchona

-

38.

Colombia

-

39.

Comoros

-

40.

Congo, Dem. Rep.

-

41.

Congo, Rep.

-

42.

Costa Rica

-

43.

Cote d’Ivoire

-

44.

Croatia

-

45.

Cuba

-

46.

Cyprus

-

47.

Czech Republic

-

48.

Denmark

-

49.

Djibouti

-

50.

Dominican Republic

-

51.

Ecuador

-

52.

Egypt, Arab Rep.

-

53.

El Salvador

-

54.

Equatorial Guinea

-

55.

Eritrea

-

56.

Estonia

-

57.

Ethiopia

-

58.

Fiji

-

59.

Finland

-

60.

France

-

61.

French Polynesia

-

62.

Gabon

-

63.

Gambia, The

-

64.

Georgia

-

65.

Germany

-

66.

Ghana

-

67.

Greece

-

68.

Grenada

-

69.

Guam

-

70.

Guatemala

-

71.

Guinea

-

72.

Guinea-Bissau

-

73.

Guyana

-

74.

Haiti

-

75.

Honduras

-

76.

Hong Kong SAR, China

-

77.

Hungary

-

78.

Iceland

-

79.

India

-

80.

Indonesia

-

81.

Iran, Islamic Rep.

-

82.

Iraq

-

83.

Ireland

-

84.

Israel

-

85.

Italy

-

86.

Jamaica

-

87.

Japan

-

88.

Jordan

-

89.

Kazakhstan

-

90.

Kenya

-

91.

Kiribati

-

92.

Korea, Dem. Rep.

-

93.

Korea, Rep.

-

94.

Kuwait

-

95.

Kyrgyz Republic

-

96.

Lao PDR

-

97.

Latvia

-

98.

Lebanon

-

99.

Lesotho

-

100.

Liberia

-

101.

Libya

-

102.

Lithuania

-

103.

Macao SAR, China

-

104.

Macedonia, FYR

-

105.

Madagascar

-

106.

Malawi

-

107.

Malaysia

-

108.

Maldives

-

109.

Mali

-

110.

Malta

-

111.

Mauritania

-

112.

Mauritius

-

113.

Mexico

-

114.

Micronesia, Fed. Sts.

-

115.

Moldova

-

116.

Mongolia

-

117.

Montenegro

-

118.

Morocco

-

119.

Mozambique

-

120.

Myanmar

-

121.

Namibia

-

122.

Nepal

-

123.

Netherlands

-

124.

New Caledonia

-

125.

New Zealand

-

126.

Nicaragua

-

127.

Niger

-

128.

Nigeria

-

129.

Norway

-

130.

Oman

-

131.

Pakistan

-

132.

Panama

-

133.

Papua New Guinea

-

134.

Paraguay

-

135.

Peru

-

136.

Philippines

-

137.

Poland

-

138.

Portugal

-

139.

Puerto Rico

-

140.

Qatar

-

141.

Romania

-

142.

Russian Federation

-

143.

Rwanda

-

144.

Samoa

-

145.

Sao Tome and Principe

-

146.

Saudi Arabia

-

147.

Senegal

-

148.

Sierra Leone

-

149.

Slovak Republic

-

150.

Slovenia

-

151.

Solomon Islands

-

152.

Somalia

-

153.

South Africa

-

154.

South Sudan

-

155.

Spain

-

156.

Sri Lanka

-

157.

St. Lucia

-

158.

St. Vincent and the Grenadines

-

159.

Sudan

-

160.

Suriname

-

161.

Swaziland

-

162.

Sweden

-

163.

Switzerland

-

164.

Syrian Arab Republic

-

165.

Tajikistan

-

166.

Tanzania

-

167.

Thailand

-

168.

Timor-Leste

-

169.

Togo

-

170.

Tonga

-

171.

Trinidad and Tobago

-

172.

Tunisia

-

173.

Turkey

-

174.

Turkmenistan

-

175.

Uganda

-

176.

Ukraine

-

177.

United Arab Emirates

-

178.

United Kingdom

-

179.

United States

-

180.

Uruguay

-

181.

Uzbekistan

-

182.

Vanuatu

-

183.

Venezuela, RB

-

184.

Vietnam

-

185.

Virgin Islands (U.S.)

-

186.

Yemen, Rep.

-

187.

Zambia

-

188.

Zimbabwe

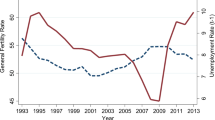

Group 1 European countries, Italy, Germany, Greece; Eastern European countries, Russia, Romania, Bulgaria; Japan.

Group 2 Anglo-Saxon countries, Scandinavia, France, Belgium, Netherlands.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Drago, C., Talamo, G. (2018). Fertility Rates Around the World: A Cluster Analysis of Time Series Data from 1960 to 2013. In: Paoloni, P., Lombardi, R. (eds) Gender Issues in Business and Economics. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65193-4_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65193-4_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-65192-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-65193-4

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)