Abstract

The experience of extreme macroeconomic instability in Africa has its origin in the inability to control fiscal dynamics and the effect that this has had on the overall policy stance. African countries are heavily dependent on volatile revenues (from aid, oil, exports, a small tax base) to finance their relatively huge total expenditure, making their budget vulnerable to fiscal shocks. This poses a serious threat both to the sustainability of the continent’s budget and to its macroeconomic stability. Oil and commodity windfalls and aid surges induce government spending that is difficult to retrench when these sources of revenue experience negative shocks, distorting government budget allocation patterns, cohesion, and stability, and increase deficits and debt stock that has often created an unfavourable environment for monetary policy. In the presence of such a highly volatile environment, current figures for revenues, expenditures, and the fiscal balances will convey a rather misleading picture of the underlying fiscal situation. Developing fiscal indicators which may provide a more reliable picture of the underlying sustainability of current fiscal policy is of paramount important. In 2004, Nigeria introduced an oil-price-based rule to deal with the revenue volatility challenge. The aim of the rule is to smooth government expenditure. The oil-price rule is designed to benchmark overall fiscal performance and the sustainability of public finances. In this chapter, we analyse the case of Nigeria’s post-2004 data to guide the development of fiscal sustainability indicators in economies with highly uncertain fiscal revenues such as Africa. In particular, we look at whether the oil-price-based rule is able to adequately address the macroeconomic conditions that affect fiscal sustainability in Africa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The special nature of oil revenue complicates evaluation of the macro-fiscal stance of oil-producing countries. An accurate assessment of this issue can be obscured by large and volatile oil revenue flows to the extent that uncertain and volatile flows complicate the management of macroeconomic policies in these countries. Given the exhaustibility of oil reserves, these countries need to address longer-term sustainability and intergenerational equity issues. Conventional fiscal indicators and tools, such as overall and primary balances and Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA), are not sufficient to make a full assessment of short-term fiscal stances or longer-term fiscal sustainability. The use of more comprehensive fiscal indicators can greatly aid addressing these notable challenges in economies with highly uncertain fiscal revenues such as those in Africa.

The design of sustainability indicators is particularly relevant when it comes to countries which operate in a highly volatile environment. Consider, for example, a temporary appreciation of the real exchange rate. In a country with a large foreign debt, a real appreciation may improve the current fiscal situation by reducing debt servicing in terms of non-tradable goods (i.e. in terms of public sector wages). In contrast, in an economy where the main source of fiscal revenue is a tradable good (such as oil), a real appreciation may well damage fiscal accounts by reducing revenues in terms of non-tradable goods. Hence, in the presence of large temporary fluctuations in the real exchange rate, a reading of the fiscal situation based on current fiscal indicators may lead to a severely distorted assessment of fiscal sustainability. This suggests a need to develop alternative fiscal indicators which may provide a more reliable picture of the underlying sustainability of current fiscal policy, particularly for Africa.

As Africa’s budgets and exports are mainly characterised by stochastic revenues, effective management of the continental fiscal revenues is critical for fiscal sustainability and macroeconomic stability.

African countries are heavily dependent on volatile revenues (from aid, oil, exports, and small tax bases) to finance their relatively large total expenditures, making their budgets vulnerable to fiscal shocks. This poses a serious threat both to the sustainability of the continent’s budget and to its macroeconomic stability.

“To deal with this volatility challenge, Nigeria, for instance, introduced an oil-price-based fiscal rule in 2004, which was later integrated into … the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) [that] was enacted in 2007” (Ibironke 2013). It was foreseen that this process would smooth government expenditure and stabilise budgetary revenue (Ibironke 2013).

However, a core question in the light of this intended stabilisation function is whether Nigeria’s oil-price-based rule can represent an adequate tool to address the macroeconomic conditions that affect fiscal sustainability in Africa. To answer this key question, an analysis of the extent to which the Nigerian oil-price-based fiscal rule has positively influenced the overall fiscal performance and sustainability of public finances in Nigeria post-2004 is essential. This chapter, therefore, evaluates the empirical relevance of the oil-price-based fiscal rule adopted by providing an analysis of post-2004 Nigerian data in order to potentially guide the development of fiscal sustainability indicators in economies with highly uncertain fiscal revenues, such as those in Africa. Analysing the case of Nigeria’s fiscal policy promises to be particularly appropriate as Nigeria is the largest country in the continent and it has relied greatly on highly volatile oil revenue since the 1970s.

The chapter is organised as follows. Section 2 “Fiscal Policy with Uncertain Revenues” analyses the implications of introducing fiscal policy rules to control budget dynamics and promote fiscal sustainability in economies with highly uncertain government revenues such as in Africa. Section 3 “Factors Responsible for the Nigerian Volatility Challenge” briefly presents the factors responsible for the challenge of volatility in Nigeria. Section 4 “Nigeria’s Oil-Price-Based Fiscal Rule” gives an overview of Nigeria’s oil-price-based fiscal rule. Section 5 “Assessment of the Effectiveness of the Oil-Price-Based Fiscal Rule” assesses the effectiveness of the oil-price rule. Section 6 “Conclusions” concludes the chapter.

Fiscal Policy with Uncertain Revenues

As a monetary policy rule intends to limit the ability of the monetary authority to act discretionally, fiscal policy rules will—if observed—mitigate the government’s tendency to abandon previous policy commitments. They seek to confer credibility on the implementation of macroeconomic policies by removing discretionary interventions. Their goal is to achieve trust by guaranteeing that fundamentals will remain predictable and robust regardless of the government in power. Thus, fiscal policy rules are particularly helpful if the government is not able to guarantee a prudent fiscal policy. It therefore seems appropriate to study the sustainability of simple fiscal rules in a case representative of many African countries, where the first source of macroeconomic instability is certainly the dynamics of fiscal policy.

Given the stochastic characteristics of government revenue in Africa, I analyse the implications of introducing fiscal policy rules to control budget dynamics and promote the necessary medium-term budget deficit stability and fiscal sustainability.

One possible way of modelling fiscal policy in Africa is to look at the effect of being dependent on natural resource revenues on the sustainability of two rules—a fixed rule and a variable rule. For example, consider a country in which about 80 per cent of its revenue comes from oil. In this case, we can safely assume that the total gross budgetary revenues for the country are equal to

where GR t is government revenue, \( {\overline{Q}}_t \) is the quantity of oil, assumed to be fixed,Footnote 1 and P t is its price. Thus, the primary surplus at the end of the budget year is equal to

Each year the government has to plan expenditure G t on the basis of a forecast of oil revenues for the period. If we assume that the price of oil follows a pure random walk, and therefore cannot be predicted, it implies that the best way to look at the predictability of the oil price changes is to assume that oil price equal to E t (P t ) = P t − 1. Following this, the expected primary surplus at the beginning of a budget year is

Inability to control fiscal revenue introduces a significant element of uncertainty into the budgetary process, equal to the volatility of oil prices v t . Any fiscal rule in this context should be tested using the budgetary process described by equation (13.3).

Once the government expenditure decision and oil prices are determined, the resulting primary surplus will give the following debt dynamic:

where R t is the real interest rate in period t and D t is the debt stock at the beginning of the period. Both PS t and D t are in real terms. In order to express equation (13.4) in terms of the output ratio, we assume a constant growth rate of output. The path of real output is then given by

where g t is the constant growth rate. Defining the debt-to-GDP ratio as d t = D t /Y t and combining equations (13.4) and (13.5),

where ps t = PS t /Y t .

Assuming too, as in Basci et al. (2004), that R t and g t have random components, we can define the random variable r t + ε t , the growth-adjusted real interest rate, using the following decomposition:

where r t is the deterministic component of the real growth-adjusted interest rate and є t is a zero-mean independently and identically distributed (iid) random variable which represents the interest rate and growth shocks.

Next, we assume that the deterministic component of the growth-adjusted mean real interest rate r(d t ) is an increasing function of the debt-to-GDP ratio (see Cantor and Packer 1996; Hu et al. 2001; Basci et al. 2004):

where r ’(d t ) represents the first derivative of r(d t ).

Combining (13.6), (13.7), and (13.8), we obtain

where d t denotes the debt-to-GDP ratio at the beginning of period t, and ps t denotes the ratio of the primary surplus to GDP in period t. It is assumed that the growth-adjusted mean real interest rate r(d t ) is an increasing function of the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Since the analysis here is limited to a developing country, a linear function of debt stock is assumed for reasons of simplicityFootnote 2:

where 0 < ρ < 1.

Now, by defining the critical or steady-state debt level (d c ) as

and combining (13.9), (13.10), and (13.11), we obtain

Given the dynamic process described by equation (13.9), we need to find the fiscal policy rule that minimises the probability of exceeding the critical debt level in equation (13.12). As in Basci et al. (2004), we consider two alternative policy rules: a policy rule that stipulates a fixed primary surplus relative to GDP, and one that adjusts the primary surplus required to the level of debt accumulated.

Fixed Fiscal Policy Rule

The fixed primary surplus rule is equal to a constant percentage of GDP, s, in every period: ps t = s for all t, as

By controlling for G t Footnote 3 our fixed expenditure rule now becomes

Equation (13.14) is the level of expenditure necessary to maintain a fixed primary surplus rule.

Variable Fiscal Policy Rule

A variable fiscal rule adjusts the expected level of fiscal surpluses to the outstanding level of debt so that a higher fiscal surplus (a tighter fiscal policy) is set as the debt stock increases. A simple linear expression of this could be

Substituting σd t for s in (13.14), our variable expenditure rule will look like

Again, equation (13.15) is the level of expenditure necessary to maintain a variable primary surplus rule.

As will be discussed in the next two sections, the Nigerian oil-price-based rule is a variable fiscal policy rule. According to the former Nigerian Minister of Finance, Ngozi Oknojo-Iweala (2013), this rule is a standard technique commonly used by commodity-dependent countries to protect themselves against the volatility of the oil price.

Factors Responsible for the Nigerian Volatility Challenge

In this section, I discuss some of the main characteristics of the Nigerian economy that have contributed to the country’s volatility problem, and which are also shared by many African countries, as identified in the literature.

The Country’s Dependence on Uncertain Oil Revenue

Nigeria is heavily dependent on oil revenue to finance over 80 per cent of its total expenditure, making its budget vulnerable to fiscal shocks. This poses a serious threat both to the sustainability of the country’s budget and to its macroeconomic stability. Oil windfall induces government spending that is difficult to retrench when the oil revenue falls, distorting government budget allocation pattern, cohesion, and stability, and increase deficits and debt stock that has often created an unfavourable environment for monetary policy (Odularu 2008; Akinlo 2012; Baunsgaard 2003; Obinyeluaku 2008; Ibironke 2013).

Due to a strong fiscal dominance in oil-producing countries, fiscal policy tends to be the main channel for propagating external shocks associated with oil price fluctuations into the non-oil economy. Empirical evidence points to a strong correlation between oil revenue and fiscal expenditure in Nigeria. Obinyeluaku (2014) shows that a higher oil revenue induces higher spending. Some studies show that higher spending exerts pressure on aggregate demand, prices, and the real exchange rate, undermining the non-oil economy (Fasano and Wang 2002). Moreover, oil price volatility transmitted to public expenditure through oil revenue has other undesirable consequences for the non-oil economy:

Macroeconomic Volatility

Sharp changes in government spending add to volatility in aggregate demand and prices, abrupt swings in the exchange rate, and increased risks faced by investors in the non-oil sector. Macroeconomic volatility has been shown to have an adverse impact on investment and economic growth (Aizemann and Marion 1993; Gavin 1997). Expenditure volatility associated with fluctuations in oil revenue is found to be a key factor explaining slower growth in oil-producing countries compared to resource-poor countries (Gelb et al. 1988; Auty and Gelb 2001; Bjerkholt 2002).

Expenditure Quality

A tendency for the quality of public spending to deteriorate during oil booms has been well documented. Introduction of large-scale new spending programmes during an oil boom can result in overstretched administrative capacity, a weakening of standards in project selection and evaluation, and even a circumvention of public financial management procedures. The result may be a rapid deterioration in the quality, efficiency, and productivity of public spending. During previous oil booms, some countries undertook ambitious investment projects with low rates of return, politically attractive payoffs, and inadequate screening and execution. Expenditure quality has also been weakened in a number of countries by a proliferation of energy subsidies.

Budget Flexibility

Expenditure increases during “good times” tend to benefit politically influential groups (e.g. civil servants, the military, farmers). For example, many oil-producing countries use oil windfalls to increase public sector wages. As these new spending programmes become entrenched, it may become difficult to curtail them when oil revenues drop sharply or dry out. In countries with high levels of statutory outlays, fiscal consolidation is often effected by cutting more productive spending categories, such as infrastructure investment and maintenance, with a possible adverse impact on growth. Another possible budget flexibility concern relates to a weakening of revenue-raising efforts during oil booms, which makes the budget more vulnerable to oil downturns.

The Small Size of the Economy

Nigeria, like any other economy in Africa, is a small open economy. It is a price taker in the world markets. Its domestic interest rate adjusts to that of the world. It has a small gross national income (GNI) per capita (Ibironke 2013).

Basically, small economies like Nigeria usually have difficulties managing external shocks. Unmanaged external shocks bring difficulties and costs to the Nigerian economy.

External imbalances, fiscal and monetary disequilibria, and inflation have been a recurrent problem because expenditure programmes have not been cut when oil prices have fallen. This has been either because the price falls were seen as temporary or because programmes were difficult to stop or reduce at the end of booms. In the 1970s and early 1980s, this problem was so severe that, even before oil prices began to fall, the excess of expenditure over revenue had become persistent, initiating the growth of Nigeria’s large stock of external debt. Given that external and internal imbalances cannot be maintained indefinitely, expenditure cuts have been unavoidable. But these cuts have been too late or too costly, or both.

Nigeria fell victim to the spending disease when oil prices and public revenues were high in the 1970s and early 1980s. Its emerging export revenues were spent on the domestic economy, particularly on non-tradable goods, increasing the relative prices of non-tradable goods and wages. Despite favouring the expansion of non-tradable sectors, such as services and construction, this response hurt the development of tradables (other than oil). Thus, Nigeria, a net exporter of agricultural products in the early 1970s, was importing more than US$ 2 billion a year in foodstuffs a decade later.

Private investment also suffered. With the public expenditure programme expanding and contracting at the whim of oil revenues, the volatility and uncertainty that plague oil earnings were channelled to the domestic economy through changes in relative prices and in the associated structure of production. If the oil shock had been permanent, the response would have been the correct one. However, because oil prices are uncertain and highly volatile, investors cannot predict when the next shock will take place. Neither can they predict the direction of the next shock or which sector will be favoured and which one hurt. This uncertainty increases the risk investors face in non-oil activities, reducing the volume of private investment and slowing the growth of the non-oil economy.

There are other macroeconomic costs too. Capital flight is often the private sector’s response to a fear that, once oil revenues fall, unsustainable budget deficits will bring inflation and higher future taxes. Moreover, there is often an unproductive political struggle among economic players trying to appropriate windfalls during the booms and to avoid losses during the busts. This process weakened decision-making in Nigeria.

A High Degree of Openness

“There are two sides to openness, namely trade openness… and financial openness...” (Ibironke 2013). Trade openness can be measured as the share of the sum of total exports and imports of merchandise goods and services in gross domestic product (GDP). “The level of Nigeria’s ... [trade openness] is relatively high (see, for example, Obinyeluaku 2008). On the other hand, the level of … [financial openness] may be estimated as the ratio of equity-based foreign liabilities to GDP (Calderon et al. 2005)” (Ibironke 2013). The recent shift in policy towards market-oriented systems has led to increasing attention to the development of efficient financial systems in developing countries. The financial sector has a key role in the savings-investment growth race by providing a channel to promote investment by raising and distributing capital. Liberalisation in Nigeria began with the relaxation of entry barriers into the financial services sector and was followed by a Central Bank relaxation of restrictions on capital inflows/outflows, interest rates, foreign exchange, and bank ownership. Since then, Nigeria has been characterised by trends of increasing liberalisation, greater openness to world trade, and higher levels of financial deepening and integration. This increased openness has motivated increases in private capital inflows and outflows, as is apparent in the fast growth of the country’s stock market capitalisation.

A High Degree of Global Integration

Nigeria’s economy is highly integrated into the global economy through the process of globalisation. The “country is currently ranked 97th in the overall globalisation rankings of the KOF Swiss Economic Institute” (Ibironke 2013).Footnote 4 This high degree of international integration, however, also leads to increased external exposure, as measured by the sensitivity of first and second moments of economic growth to openness and foreign shocks. This vulnerability is particularly important in Nigeria due to its production specialisation, non-diversified income sources, unstable policies, incomplete financial markets, and weak institutions.

The Emerging Market Feature

Nigeria has been described by the international financial institutions (the International Monetary Fund, IMF, and the World Bank) as one of the 11 countries to watch out for in the next decade (IMF 2013a, b). Lucrative investment ventures are rife, and their development potential continues to rise.

Impressive growth has been recorded in the emerging capital markets in this petrodollar-rich sub-Saharan nation of prestigious natural resources, offering very attractive opportunities for market operators and investors. Regarded as the second most impressive after South Africa, these markets, which had hitherto been closed to foreign investors (functioning solely as a government auction/trading post for treasury securities and equity shares of statutory corporations and foreign subsidiary companies), were restructured to allow for the participation of free market institutions after 1999 when the country returned to civilian rule. This was the best time to invest in the country, especially in the financial services industry as an engine of wealth creation. Several foreign companies lucratively partnered with indigenous brokers to trade in equities and government bonds. The problems that occurred in the advanced capital markets in the world—USA, Europe, and Asia—have generated compelling arguments for the participation of foreign investors in emerging capital markets. These markets offer profit-making opportunities for asset diversification. The market potential in the country is huge, with investment opportunities even in the real sector—power, housing, agriculture, transportation, and tourism.

Nigeria’s relevance in the oil market has brought it much attention. It is the 5th largest exporter of crude oil to the USA. In addition, the country’s GDP has grown at an average annual rate of 8 per cent for five consecutive years. Foreign investment has poured in, especially from the USA, which is Nigeria’s largest foreign investor. However, the bulk of investment is in the oil sector of the economy.

Nigeria’s Oil-Price-Based Fiscal Rule

Nigeria is heavily dependent on oil revenue to finance over 80 per cent of its total expenditure, making its budget vulnerable to fiscal shocks. A strong deficit and debt bias stemming from government revenue volatility hence poses a serious threat to the country’s budgetary sustainability. An oil windfall induces government spending, which in turn is difficult to reduce when the oil flow declines, distorting government budget allocation patterns and increasing deficits and debt.

To deal with this challenge of volatility, Nigeria, for instance, introduced an oil-price-based fiscal rule in 2004, which was later integrated into the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) that was enacted in 2007 (Nigerian National Assembly 2007). It was expected that this process would smooth government expenditure and stabilise budgetary revenue (Ibironke 2013).

Through the determination of a domestic crude oil benchmark for budgeting, various endogenous and exogenous factors became influential in pegging the benchmark in the Nigerian budgeting process. These factors include the social and economic objectives of the government, the costs of oil production, joint-venture agreement considerations, oil production during the contract period, non-oil sector viability, and the overall fiscal stance of the government. The interplay of these variables affects not only the crude oil benchmark for budgeting, but also the government’s revenue stream projections in its fiscal planning.

Put differently, the Nigerian oil-price-based fiscal rule stresses “that annual fiscal expenditure is restrained through a reference oil price” (Ibironke 2013). It uses projections of the oil price that are lower than the expected international price over the budget period. The benchmark price is a result of some rigorous analysis that develops a ten-year moving average oil price (Ibironke 2013). In 2004, based on these calculations, the government budgeted at a price of US$25. Subsequently, the figure was US$30 in 2005, US$35 in 2006, US$40 in 2007, US$72 in 2012, and US$75 in 2013.

When oil revenues are high such that the actual oil price is above the benchmark price, the resulting surplus “is kept in a special ‘Excess Crude Oil Account’ (ECA), which is also known as the ‘Sovereign Wealth Fund’” (Ibironke 2013). When oil revenues are low, the ECA would finance the shortfall (Ibironke 2013). According to the previous administration’s Minister of Finance, Ngozi Oknojo-Iweala (2013), this way of proceeding is a standard technique commonly used by commodity-dependent countries to protect themselves against oil price volatility.

The benchmark oil price is usually determined by the executive arm of the government. This method, and especially the role of the government within it, has, however, been criticised for being highly subjective, lacking transparency and not being based on generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). This has often resulted in heated debates and intensive negotiations between the executive and the legislative arms of government, and frequently led to delays in the release of the appropriation bill. For example, while legislative actors had proposed a US$79 per barrel oil price benchmark for the 2014 budget, the executive branch required US$75, but ended up with $77.5 in the final appropriation. The 2014 budget was delayed due to this mismatch.

Following consultations with various stakeholder groups, including governors and the National Assembly, the president finally approves the benchmark budgeted oil price, which in turn places a limit on government expenditure.

During the budget process, ministries, departments, and agencies (MDAs) of government receive “expenditure envelopes” from which they are to satisfy their financial needs, including salaries. These expenditure envelopes cater for the priority level accorded to the services to be delivered by the MDAs as articulated in their Medium-Term Sector Strategies (MTSS) against the background of the priorities of the federal government (FG) as documented in the National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The allocation of these envelopes is determined by the benchmark oil-price-based rule.

In general, government oil revenues are allocated to four main areas: (a) federal, state, and local budgets, and extra-budgetary funds; (b) cash calls from the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation, NNPC (to finance expenditure and investment in the oil sector); (c) the fuel subsidy; and (d) the Excess Crude Account (ECA). Allocations to the ECA can be either positive (accumulation) or negative (drawdowns), which augment the oil revenue allocated to other directions. The dynamics of the distribution of oil revenues reflect different factors and policies that form priorities in the year in question. For example:

-

In 2008, oil revenues surged due to record high prices, supporting exceptionally large collections to budgets and an accumulation to the ECA (3.4 per cent of GDP).

-

In 2009, in the light of a sharp decline in output and revenues, significant allocations from the Federation Account and fuel subsidy payments were financed by large drawdowns of the ECA (5.7 per cent of GDP).

-

In 2010, an increase in oil prices was not sufficiently significant to finance large increases in allocations to budgets and higher fuel subsidy payments, entailing another drawdown of the ECA of 2.7 per cent of GDP.

-

In 2011, oil prices and revenues increased notably. Large increases in allocations to budgets and a major surge in payments of the fuel subsidy (4.6 per cent of GDP) limited accumulation in the ECA to only 1.3 per cent of GDP.

-

In 2012, oil output and revenues dropped but the government did not deplete the ECA, which accumulated another 1.5 per cent of GDP.

A thorough analysis of the ECA from its inception in 2004 onwards shows that the FG has continuously augmented its distributable revenue from the ECA due to shortfalls in the production of petroleum products and tax income. Between 2005 and 2008, the savings in the ECA rose from $5.1 billion to $20 billion, but due to continual drawdowns the account cascaded down from US$20 billion to US$4.1 billion in 2014.

Assessment of the Effectiveness of the Oil-Price-Based Fiscal Rule

Whether an oil-price-based fiscal rule such as the Nigerian one can serve to address the macroeconomic conditions that affect fiscal sustainability in Africa also depends on the extent to which this rule is assessed to have positively influenced the macroeconomic performance of Nigeria after 2004. The following section looks at the post-2004 performance of the Nigerian oil-price-based fiscal rule with respect to its original objectives and its impact on fiscal outcomes. The analysis is based on (a) the extent of macro-fiscal vulnerabilities, (b) controllability and fiscal consolidation, (c) the cyclical properties of fiscal policy, (d) the balance of payments, and (e) inflation.

The Extent of Macro-Fiscal Vulnerabilities

Does Nigeria face a volatile macroeconomic environment? And, if so, is this environment more volatile than before the introduction of the oil-price-based fiscal rule in 2004? Tables 13.1 and 13.2 summarise differences in variability by listing the volatilities of government expenditure and revenue together with other macro variables, including annual consumer price inflation, the nominal effective exchange rate and GDP growth.

As one of the countries with the highest revenue volatilities, a key priority for fiscal policy should be to protect the budget from such volatility. In particular, the oil-price-based fiscal rule is expected to restrain government expenditure through oil revenue smoothing, which involves setting a volatility-absorbing reference oil price through which resource revenues will be channelled into the budget in order to avoid the destabilisation effect of fiscal shocks on monetary policy and macroeconomic stability. In practice, Nigeria has, on average, not only been able to limit volatility in expenditure since 2004 but revenue volatility has even exceeded expenditure volatility (see Table 13.1). This suggests that the oil-price rule is capable of limiting the impact of the volatility of revenue on the budget.

Furthermore, Table 13.2 shows that on average the volatilities of inflation, the nominal effective exchange rate, and output are lower after 2004 compared to the pre-2004 period, with the country almost doubling its GDP growth post-2004. As a result, Nigeria seems to have been facing a less volatile macroeconomic environment since the introduction of the oil-price rule in 2004.

Controllability and Fiscal Consolidation

A strong deficit and debt bias stemming from government revenue volatility poses a serious threat both to the sustainability of Nigerian fiscal policy and to macroeconomic stability. The oil-price rule is considered an important element of budgetary consolidation as it limits the political scope and reduces the deficit and debt bias while ensuring that a fiscal reserve of adequate size is accumulated to protect Nigeria from oil price volatility and prevent the government from losing control over its budget.

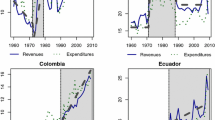

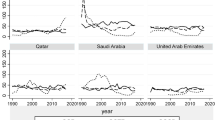

The evidence shown in the previous section suggests that low expenditure volatility seems to have coincided with better fiscal outcomes in Nigeria after the introduction of the oil-price rule. The post-2004 period has witnessed a persistent decline in fiscal deficit in Nigeria (Fig. 13.1).Footnote 5 Public revenue consistently exceeded expenditure except for 2010, 2013, and 2014. Government revenue increased from an average of 13.5 per cent of GDP before the introduction of the oil-price rule (pre-2004) to 16.4 per cent after 2004. At the same time, public expenditure declined to reach 13.5 per cent of GDP after 2004. Consequently, the fiscal deficit turned into a surplus and debt stock to GDP declined significantly over the same period under review (Fig. 13.1).

According to the IMF’s Debt Sustainability Analysis, the risk of debt distress remains low (IMF 2015). Total annual debt post-2004 (pre-2004) was 13.5 per cent (48.8 per cent) of GDP, with external debt, mostly from International Financial Institutions (IFIs) on concessional terms, at only 3.7 per cent (34.8 per cent) of GDP. However, about 30–40 per cent of the FG domestic debt was held by non-residents at the end of 2013. Moreover, FG debt servicing on total public debt was 5.6 per cent (9.6 per cent) of general government revenue.

However, a vital question remains whether the adjustments occurred on the right side of the budget. This is of importance as the composition of the adjustment affects the success and durability of government budget consolidation (Von Hagen et al. 2002; Perotti et al. 1998). Von Hagen et al. (2002) and Perotti et al. (1998) have demonstrated that consolidation relying on expenditure cuts is more likely to lead to a permanent reduction in deficit and ensure fiscal sustainability than consolidation based on raising additional revenue. This finding calls for disaggregation of the main deficit components in order to ascertain what is driving the adjustments in the post-2004 period. The results are presented in Table 13.3.

This table contains three clear messages. First, the size of the fiscal surplus (2.91 per cent) witnessed after the introduction of the oil-price rule (post-2004) is virtually driven by both expenditure cuts (−2.89 per cent) and increased revenue (2.95 per cent). The second message concerns the composition of the expenditure cuts. Cuts in capital expenditure contribute more than 100 per cent to the decline in expenditure after 2004. Recurrent expenditures, by contrast, behave in the opposite way, increasing overall expenditure by 1 per cent. The third point concerns disaggregation of revenue. The contribution of revenue to the fiscal surplus after 2004 is driven by oil revenues. However, non-oil revenues declined by 0.31 per cent over the same period. With oil production below the budget target of 2.38 million barrels per day (bpd) and the continual decline in oil prices, Nigeria needs to reduce its dependency on oil revenues and ensure there are measurable increases in non-oil revenues, and also reverse the trend of increasing recurrent expenditure and declining capital expenditure.

The Cyclical Properties of Fiscal Policy

A high dependence on resource exports is often associated with lower growth and greater economic instability due to “boom-bust” government spending resulting from highly volatile commodity prices. Countercyclical fiscal policy (expansionary when growth is below the trend and contractionary in good times) is generally desirable because it helps to smooth output volatility.

By introducing automatic revenue stabilisers, Nigeria’s oil-price rule and the resultant ECA are expected to ensure a more countercyclical fiscal policy. Positive allocations to the ECA (or accumulation) are likely to mitigate the overheating of the country’s economy from exceptionally high oil prices during “boom” periods, while negative allocation to the ECA (or drawdowns) can ensure macroeconomic stability during “bust” periods by maintaining strong growth in domestic demand and GDP.

The extent to which policies are countercyclical is typically measured by correlations between cyclically adjusted measures of government activity and the output gap.Footnote 6 The output gap is measured as deviations between output levels from their long-run trends using the Hodrick-Prescott filter (Kaminsky et al. 2004). Economic downturns or recessions are defined as periods where output gaps are negative (or where growth is below the trend). The opposite is the case for an economic boom. Table 13.4 summarises the resulting cyclical fiscal patterns.

Figure 13.2 indicates that fiscal policy in Nigeria remained mostly procyclical even after the introduction of the oil-price rule. Through the establishment of the ECA fiscal reserve, the country made a positive step during 2005–2008 that successfully insulated it from the sharp swings in oil prices during this period. However, despite the recovery in oil prices in 2010, Nigeria expanded its fiscal stimulus significantly, increasing consolidated spending by 21 per cent in real terms and drew down the ECA at the same time that many other exporters were building back their reserves.

The limited degree of accumulation undermined the ability of the country to ensure stability during the period of declining oil prices and output in 2013–2014. For example, the ECA reached $2.0 billion by the end of 2014—well below the $6.3 billion required to cover a one-half standard deviation shock to oil receipts.Footnote 7

The Balance of Payments

Nigeria’s high dependence on inherently volatile oil revenues presents major balance of payments risks to the country. A sharp decline in oil prices not only has a strong impact on its current account but on the capital account too, as the general attitude of investors towards the country critically depends on oil prices and the capacity to manage the risks of oil-price volatility.

Figure 13.3 shows that Nigeria’s balance of payments position has strengthened along with the improved management of fiscal policy since the introduction of the oil-price rule in 2004. Between 2005 and 2008, the balance of payments was in surplus, allowing the Central Bank to build its foreign reserve position from US$ 6.8 billion on average in 1995–2003 to US$ 43.7 billion in 2005–2008.

However, despite the recovery in oil prices in 2010–2011, which enabled many other oil-dependent emerging markets to restore a balance of payments equilibrium, Nigeria’s balance of payments remained in deficit and the country lost US$ 0.3 billion in foreign reserves. As previously discussed, with stronger oil prices, Nigeria actually expanded its fiscal stimulus in 2010–2011, drawing not only on higher oil revenues but also on the balance of its ECA. Consequently, imports recovered and the balance of payments declined, putting pressure on Nigeria’s currency, the Naira.

In 2012, the country began to re-accumulate its fiscal reserves, which had a notably positive effect on the expectations of investors. Combined with other factors, this development started attracting substantial foreign inflows to the government bond market. Portfolio investment inflows to Nigeria increased from 792.4 billion Naira in 2011 to 2.7 trillion in 2012. These inflows, against the backdrop of tighter fiscal policy, primarily explain the widening of the country’s balance of payments surplus in 2012, despite somewhat weaker oil prices.

By 2013 and 2014, the continued decline in oil prices and revenues had led to a limited degree of accumulation, and drawdowns, adversely affecting investor confidence, culminated in an abrupt reverse of the short-term inflows, thereby magnifying the oil-price-related balance of payments swings.

Nigeria faces a medium-term challenge in managing its balance of payments. Given the present declining oil prices and export demand, the pace of import growth is likely to exceed export growth for some years ahead. Thus, the prevailing balance of payments deficit is very likely to continue, and more exchange rate flexibility might be necessary over the longer term. Moreover, its economy needs to be diversified.

Inflation Performance and Monetary Policy

Consumer price inflation (CPI) has remained stubbornly high in Nigeria (Fig. 13.4). Contrary to some expectations, given the tightening of monetary policy, CPI (year-on-year) has been at an average of 11 per cent during the post-2004 period compared to 20 per cent between 1995 and 2003.

In a context of poor weather conditions in Nigeria and increases in world food prices, high food prices drove inflation up in 2008. Despite declining food and commodity prices, the continued high inflation in Nigeria in 2010 no doubt reflected the strong fiscal expansion in that year. Monetary policy was also eased in the context of the Nigerian banking crisis that unfolded in 2009, but without any corresponding rapid expansion in money supply or credit that could have been inflationary. The inflation rate dropped in 2011 in the context of both fiscal and monetary tightening, but increased again in 2012. Part of the explanation for this development concerns one-off effects on inflation of administrative increases in petrol prices (50 per cent reduction of the fuel subsidy) and electricity tariffs. In addition, severe flooding and security challenges in parts of the country reduced the supply and trading of some goods. Driven by the decline in food and commodity prices, the inflation rate began a steady fall again in 2013.

Conclusions

This chapter has analysed whether the Nigerian oil-price-based fiscal rule is able to adequately address the macroeconomic conditions that affect fiscal sustainability in economies with highly uncertain fiscal revenues, such as those in Africa. The findings show that it has been effective in Nigeria and that it therefore can assist in contributing to improved macroeconomic conditions in other similar economies in Africa. The rule introduces some element of flexibility in the way expenditure is planned, and offers a much less stringent constraint on the policy-maker. The high degree of macroeconomic stability in Nigeria in the past decade directly reflects important progress in this direction, but remaining institutional weaknesses still need to be addressed.

The country needs to overcome the political bias and private interests involved in the determination of the benchmark oil price. The government of Nigeria has been finding it increasingly difficult to adhere strictly to and accurately forecast revenue accruals based on the benchmark oil-price rule for each fiscal year. It sets a benchmark price that either overshoots or undershoots the level that is consistent with the expected revenue for the fiscal year or 3-year medium-term expenditure framework. Since the success of this fiscal rule is dependent on the consistency with which the benchmark mimics the volatile and exogenously determined international price of crude oil, an accurate forecast of this crude oil price is crucial to the continued achievement of the predetermined overall fiscal performance in Nigeria. It would be constructive to limit the yearly debate and conflicts surrounding budget preparation over the choice of an appropriate benchmark price through legislation that fixes the allocation rule for a longer period of time.

At present, Nigeria faces both the challenge of (highly likely) declining oil revenues relative to GDP and the imperative to build a sufficient fiscal reserve to ensure macroeconomic stability. Planning a high rate of real growth in the distribution of oil revenue to budgets and the resultant depletion of the oil savings account (ECA) would put fiscal sustainability at risk. As such, the recent withdrawal of the fuel subsidy is a step in the right direction. A sufficient reserve has to be accumulated to insulate the country from sharp swings in oil prices. International experience in oil-dependent countries suggests that countercyclical fiscal policy is the key to conquering the “oil curse” of periodic instability.

Having said that, non-oil revenue is just 4.5 per cent of non-oil GDP—compared to an average of 10–15 per cent of non-oil GDP for other oil producers. Given that oil revenues are due to become increasingly low relative to the size of the Nigerian economy, non-oil revenue mobilisation will become a key fiscal priority in the period ahead. The task of building a strong domestic tax system at the federal and subnational levels and efforts to diversify the economy become increasingly critical.

With the above lessons in mind, the Nigerian oil-price-based fiscal rule can function as a pan-African indicator of fiscal sustainability. It can play a role in stabilising expenditure programmes at levels consistent with the necessary medium-term deficit stability. The oil-price-based fiscal rule will, if observed, mitigate the tendency of democratic governments to abandon previous policy commitments as it introduces a long-term horizon to governments’ often short-sighted decision-making processes. It seeks to confer credibility on the conduct of macroeconomic policies by removing discretionary interventions. The goal is to achieve trust by guaranteeing that fundamentals will remain predictable and robust regardless of the government in power.

Notes

- 1.

As it is exogenous and determined by OPEC not the government.

- 2.

It is also assumed that the real interest rate is independent of the fiscal rule adopted.

- 3.

We cannot control for P t (Q t ) due to oil price volatility.

- 4.

The overall globalisation index comprises economic, social, and political globalisation. Nigeria ranked 82nd, 184th, and 25th, respectively, according to the 2015 study.

- 5.

The fiscal deficit consists of the primary deficit and interest payments on outstanding government debt.

- 6.

Measured as the difference between actual and potential growth.

- 7.

However, the fiscal authorities responded swiftly to the oil-price developments by submitting a revised 2015 Medium-Term Expenditure Framework (MTEF) in December, with a benchmark oil price of $65 per barrel (pb) compared to the $78 pb in the original MTEF (submitted in October).

References

Aizemann, J., & Marion, N. P. (1993). Policy Uncertainty, Persistence, and Growth. Review of International Economics, 1(2), 145–163.

Akinlo, A. E. (2012). How Important Is Oil in Nigeria’s Economic Growth? Journal of Sustainable Development, 5(4), 165–179.

Auty, R. M., & Gelb, A. H. (2001). Political Economy of Resource-Abundant States. In R. M. Auty (Ed.), Resource Abundance and Economic Development. Study Prepared for the World Institute for Development Economics Research of the United Nations University (pp. 126–146). New York: Oxford University Press.

Basci, E., Fatih Ekinci, M., & Yulek M. (2004). On Fixed and Variable Fiscal Surplus Rules (IMF Working Paper, WP04/117). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=17489.0

Baunsgaard, T. (2003). Fiscal Policy in Nigeria: Any Role for Rules? (IMF Working Papers, WP/03/155). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Retrieved from https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=16728.0

Bjerkholt, O. (2002). Fiscal Rule Suggestions for Economies with Non-Renewable Resources. Paper Prepared for the Conference “Rules-Based Fiscal Policy in Emerging Market Economies”, 14–16 February. Oaxaca.

Calderon, C., Loayza, N., & Schmidt-Hebbel, K. (2005). Does Openness Imply Greater Exposure? (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper WP/3733). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Cantor, R., & Packer, F. (1996). Determinants and Impact of Sovereign Credit Ratings. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, 2(2), 37–54.

Fasano, U., & Wang, Q. (2002). Testing the Relationship Between Government Spending and Revenue: Evidence from GCC Countries (IMF Working Paper 02/201). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Gavin, M. (1997). A Decade of Reform in Latin America: Has It Delivered Lower Volatility? (Inter-American Development Bank Working Paper Green Series, No. 349). Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Gelb, A., et al. (1988). Oil Windfalls: Blessing or Curse? New York: Oxford University Press for the World Bank.

Hu, Y. T., Kiesel, R., & Perraudin, W. (2001). The Estimation of Transition Matrices for Sovereign Credit Ratings. Journal of Banking and Finance, 26(7), 1353–1406.

Ibironke, A. (2013). How Effective Is the Nigerian Oil-Price-Based Fiscal Rule? (Research Paper). Newcastle: Newcastle University Business School. Retrieved from https://editorialexpress.com/cgi-bin/conference/download.cgi?db_name=CSAE2014&paper_id=888

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2013a). International Financial Statistics. Washington, DC: IMF. Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/en/Data

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2013b). World Economic Outlook. Washington, DC: IMF. Retrieved from www.imf.org

International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2015, February). Staff Report for the 2014 Article IV Consultation-Debt Sustainability Analysis. Washington, DC: IMF.

Kaminsky, G. L., Reinhart, C. M., & Végh, C. A. (2004). When It Rains, It Pours: Procyclical Capital Flows and Macroeconomic Policies (National Bureau of Economic Research, NBER, Working Paper No. 10780). Washington, DC: NBER. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w10780

Nigerian National Assembly. (2007, July 19). Fiscal Responsibility Act, 2007: Act No. 31. Abuja: Nigerian National Assembly.

Obinyeluaku, M. (2008). Fiscal Policy Rules for Managing Oil Revenues in Nigeria. Paper Presented at the CSAE Conference on Economic Development in Africa, 16–18 March. Oxford: St Catherine’s College, Oxford University.

Obinyeluaku, M. (2014). Monitoring Fiscal Sustainability in Africa. In A. B. Elhiraika (Ed.), Regional Integration and Policy Challenges in Africa (pp. 278–301). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Odularu, G. O. (2008). Crude Oil and the Nigerian Economic Performance. Oil and Gas Business Journal, (1). Retrieved from http://ogbus.com/article/crude-oil-and-the-nigerian-economic-performance/

Okonjo-Iweala, N. (2013). Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala Justifies Nigeria’s Budget Oil Price. African Spotlight. Retrieved from www.africanspotlight.com/2012/10/15/ngozi-okonjo-iweala-justifies-nigerias-2013-budgeted-oil-price/

Perotti, R., Strauch, R., & Von Hagen, J. (1998). Sustainability of Public Finances (No. 1781). Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Von Hagen, J., Hughes Hallet, A., & Strauch, R. R. (2002). Budgetary Consolidation in Europe: Quality Economic Conditions and Persistence. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 16(14), 512–535.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Obinyeluaku, M. (2018). Developing an Indicator of Fiscal Sustainability for Africa. In: Malito, D., Umbach, G., Bhuta, N. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Indicators in Global Governance. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62707-6_13

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62707-6_13

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-62706-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-62707-6

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)