Abstract

When looking at teaching and learning processes in mathematics education students with mathematical learning difficulties or disabilities are of great interest. To approach the question of how research can support practice, an important step is to clarify the group or groups of students that we are talking about. The following contribution firstly concentrates on the problem of labelling the group of students having mathematical difficulties as there does not exist a single definition. This problem might be put down to the different roots of mathematics education on the one hand and special education on the other hand. Research results with respect to concepts and models for instruction are multifaceted and related to specific content and mathematical topics as well as underlying views of mathematics. Taking into account inclusive education, a closer orientation to mathematical education can be identified and the potential of selected teaching and learning concepts can be illustrated. Beyond this, the role of the teacher and the corresponding teacher education programs are discussed.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction: Mathematics Learning, Special Education and Inclusion—Setting the Scene

The following paper reports part of the work of the survey team “Assistance of students with mathematical learning difficulties—How can research support practice?” for ICME-13. When starting the work, the important aspects of defining students with mathematical learning difficulties, the role of teachers and teacher education programs as well as effective teaching programs and concepts of what teacher effective means came into the focus. Looking back to the ICME conferences of the last 20 years, we identified contributions in the corresponding topic study groups or discussion groups. It became obvious that we would have to take into account different disciplines; alongside mathematics education, special education, psychology and pedagogy also play important roles. Our aim was

-

to describe definitions of mathematical learning difficulties and the problem of labelling,

-

to discuss findings related to effective teaching practices and intervention strategies,

-

to discuss concepts of assistance in the context of inclusive education, and

-

to draw conclusions for teacher education.

Our paper is organized as follows: First, we discuss various definitions and assumptions concerning mathematical learning difficulties or disabilities. In Section “Effective Mathematics Teaching for All Students”, we present a synthesis of results of selected meta-analyses and intervention studies, followed by some reflections upon the meaning of inclusive mathematics education and the kinds of learning environments that can support it. We conclude with implications for teacher education and perspectives for future research.

Mathematical Learning Difficulties: Definitions and Usage

In the title of this paper the term “students with mathematical learning difficulties” has been chosen to point to a group of learners perceived as being in particular need of assistance. But who is included in this group? In the first instance, we might interpret the term “students with mathematical learning difficulties” to be synonymous with terms such as “students with mathematical disabilities” or “students with special needs in relation to mathematics”, but a closer look at the terms and the contexts in which they are used reveals that they may be associated with different approaches to teaching and learning, and to whether difficulty in learning mathematics is seen essentially as an individual attribute or as a consequence of barriers imposed by society (for this discussion see also Gervasoni & Lindenskov, 2011).

When the question of diagnosis is at the forefront, it is medical models and models which posit achievement as something inherent to the individual that tend to dominate. For example, according to 10th International Classification of Diseases (ICD 10, WHO, 2016), amongst the entries associated with specific developmental disorders of scholastic skills, is the category specific disorder of arithmetical skills (F81.2). This disorder is described as a “specific impairment in arithmetical skills that is not solely explicable on the basis of general mental retardation or of inadequate schooling. The deficit concerns mastery of basic computational skills of addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division rather than of the more abstract mathematical skills involved in algebra, trigonometry, geometry, or calculus” (ICD 10, WHO, 2016).

This definition is used as a basis for the widespread, if heavily criticised, use of the IQ-discrepancy model, where a mathematical learning disorder is diagnosed as a result of a discrepancy between IQ and mathematics performance level. Critics of this model argue that it can lead to over-identification at upper levels and under-identification at lower levels of IQ and that it leaves unspecified the point at which a discrepancy becomes significant (Francis et al., 2005). They also question whether the differences in IQ levels, permit the identification of the particular characteristics of different student groups (Murphy et al., 2007).

In the light of such criticisms, another influential classification system, the fifth Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM V) published by the American Psychiatry Association (APA), no longer makes use of the discrepancy model. In previous versions, what was called a mathematics disorder was listed, however, in DSM V, this has been redefined as one of the subtypes of a “specific learning disorder”, that is, a neurodevelopmental disorder that impedes the ability to learn or use specific academic skills. The symptoms are described as follows:

Difficulties mastering number sense, number facts, or calculation (e.g., has poor understanding of numbers, their magnitude, and relationships; counts on fingers to add single-digit numbers instead of recalling the math fact as peers do; gets lost in the midst of arithmetic computation and may switch procedures). Difficulties with mathematical reasoning (e.g., has severe difficulty applying mathematical concepts, facts, or procedures to solve quantitative problems) (DSM V, 2016).

The changes from the DSM IV to the DSM V definitions of learning disorders reflect the lack of consensus as to the precise nature of the so-called specific learning disorders and the problems that arise when learning difficulties in mathematics are treated using exclusively neuropsychological perspectives. Healy and Powell (2013) reviewed some of the critiques and pointed to problems such as the lack of a robust consensus around characteristics of so-called disorders (Mazzocco & Myers, 2003; Gifford, 2005), the use of standard calculation procedures in diagnostic procedures (Ellemor-Collins & Wright, 2007; Gifford, 2005), the assumption that learning can be expected to be homogenous (Dowker, 2004; Ginsburg, 1997) and the failure to recognize environmental and socio-emotional factors (Kaufmann et al., 2013).

In the light of the difficulties associated with definitions which reside in the medical rather than educational community, recent publications of the Eurydice NetworkFootnote 1 suggest the use of a broader concept of mathematical difficulties, using the term to refer to any group of students with low achievement in mathematics:

Low achievement is the situation where a child fails to acquire basic skills while they do not have any identified disability and have cognitive skills within the normal range. In those cases, low achievement may be considered as a failure of the education system (European Commission, n. d., p. 4).

This definition stresses how, regardless of the causes, it is important to offer students with mathematical learning difficulties environments that enable them to thrive mathematically. How then might the teaching community intervene in ways that enable students to negotiate the difficulties they experience? To explore this question, the next section focuses on the results of studies into interventions aimed at improving the performance of students with mathematical learning difficulties.

Effective Mathematics Teaching for All Students

In this section we briefly review the results from meta-analyses and consider the findings of particular studies at various levels of schooling, that illustrate the complex conditions surrounding special education teaching before discuss inclusive education.

What Do We Know About Effective Teaching Practices in Mathematics Classrooms?—Intervention Studies

The absence of a generally accepted definition of mathematical learning disabilities implies a cautious approach is adopted when comparing results from different studies, particularly since intervention studies have pursued different objectives arising from different views of teaching and learning mathematics, the choice of the topics for the interventions, and the settings investigated.

According to the meta-analyses of Kroesbergen and Van Luijt (2003) and Gersten et al. (2009), direct instruction, self-instruction or explicit instruction led to practically and statistically important increases in effect size. However, it is not always clear what is meant by “guided instruction” or “explicit instruction”. Whilst some authors understand it in the sense of scaffolding, others understand explicit instruction in a narrow way.

Kroesbergen and Van Luijt (2003) observed that the majority of interventions studies have concerned the field of basic arithmetic skills. Some of these studies have examined only the impact of training for procedural competencies like retrieval (Fuchs et al., 2009, 2010). Long-term effects have not been investigated in these studies and no information is available as to whether the students actually improved with fact retrieval, or simply used counting strategies more quickly. Other research (e.g., Andersson, 2010) has underscored the importance of fostering the domains of conceptual knowledge (e.g., place value, base-ten system, relationships within and between arithmetic operations) and procedural knowledge. The research undertaken by Ennemoser and Krajewski (2007), Pedrotty Bryant et al. (2008), Wißmann et al. (2013) and Pfister et al. (2015) showed significant effects for such interventions with primary school students. Intervention studies at secondary level have often focused on direct instruction and “drill and practice” teaching (Maccini et al. 2007). Nevertheless, Woodward and Brown (2006) and Moser Opitz et al. (in press) reported having successfully implemented a middle school program emphasizing conceptual understanding of primary arithmetic and problem solving.

With regard to the settings in which interventions have been implemented, research results are inconsistent. For example, a meta-analysis by Ise et al. (2012) of studies from German-speaking countries showed one-to-one training to have advantages over small group interventions, computer-based programs, and interventions integrated into the classroom. However, Moser Opitz et al. (in press) found a significant effect for an intervention in middle school which was partly integrated in the classroom teaching.

Taken together these results present challenges: First, it is not always clear what is meant by “guided instruction” or “explicit instruction”. Second, even if some of the studies focus on conceptual understanding, the interventions reported do not cover the whole range of mathematical domains, but focus on topics that are known to be “stumbling blocks” for many—but not for all—students with learning difficulties in mathematics. Developing interventions for students with learning difficulties in mathematics is, therefore, a “balancing act” between giving guidance and taking into account the learners strategies and concepts; and focussing on well known “stumbling blocks” without forgetting that mathematics means more than arithmetic.

Inclusive Education

The UNESCO International Bureau of Education (2009) defined inclusive education is “an ongoing process aimed at offering quality education for all while respecting diversity and the differing needs and abilities, characteristics and learning expectations of students and communities, eliminating all forms of discrimination” (p. 18).

As with the terms “learning disabilities in mathematics” and “mathematical learning difficulties” there does not exist a common understanding of the term “inclusive education” (Ainscow, 2013) and there are many possible ways of viewing the notion of inclusion. For example, conceptions are likely to be mediated by factors such as the organisation of the school system (differentiated or comprehensive), legal regulations related to the provisions for students eligible for special education, policies related to the progression between grades (exam-based or age-based) and practices related to the organisation of classes (mixed-ability or streaming). Skovsmose (2015) has argued that inclusion represents an example of what he calls a contested concept, a concept that can be given different interpretations that operate in different ways in different discourses. For him, contested concepts represent controversies that can be of a profound political and cultural nature. His view of inclusion is one that rejects the idea of bringing learners into some (politically) presumed “normality”. “Instead inclusive education comes to refer to new forms of providing meetings among differences” (Skovsmose, 2015, p. 7). In the remainder of this section, we consider some attempts to construct learning situations that permit such meetings.

Substantial and Rich Learning Environments—Multiple Opportunities

Constructivist and socio-constructivist theories open ways of viewing “knowing” (Ernest, 1994; Von Glasersfeld, 1995) and learning in a social environment (e.g., Wittmann, 2001). For mathematics education, investigative learning and productive practicing are seen as the main elements of these paradigms (e.g., Wittmann, 2001). Productive practicing is to be understood in contrast to bare reproduction of knowledge. It should enable pupils to think, to construct and to extend their knowledge. The teacher has to offer learning situations, that enable the students to make discoveries but this requires that the student possesses powerful tools in the form of (context)-models, schemes, and symbols (Streefland & Treffers, 1990, p. 313f).

With respect to heterogeneous learning groups, several studies have confirmed that investigative learning combined with productive practicing is appropriate for all learners—especially for low achievers and children with special needs (e.g., Ahmed, 1987; Moser Opitz, 2000; Scherer, 1999, 2003; Scherer & Moser Opitz, 2010, p. 49 ff.; Trickett & Sulke, 1988; Van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, 1991). According to this view all learners should be confronted with complex learning environments characterised by investigative learning and productive practicing. Such holistic approaches to mathematics teaching and learning require all learners to see relationships between numbers, shapes, and so forth in order to understand mathematical structures (Trickett & Sulke, 1988, p. 112).

Taking into account some of the research reviewed in the Sections “What Do We Know About Effective Teaching Practices in Mathematics Classrooms?—Intervention Studies” and “Inclusive Education”, it seems that there still exists scepticism with respect to constructivist or socio-constructivist approaches for students with mathematical learning difficulties. For example, although the results of Kroesbergens’s and van Luijt’s meta-analysis (2003) suggest that direct instruction could be the most beneficial type of instruction for these students, this conclusion neglects the fact that students with mathematical learning difficulties profit from teaching specific cognitive learning strategies like self-regulated learning (see Mitchell, 2014).

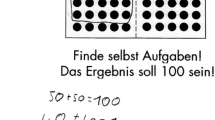

Moreover, to identify children’s existing difficulties, it is necessary to give them opportunities to show what they are capable of. More attention should be paid to the creation of substantial and rich mathematical learning environments for inclusive settings, in which different learning trajectories and different forms of interacting with mathematical objects are explicitly recognized (Fernandes & Healy, 2016). The development of such environments is crucially dependent upon differentiation. Learning tasks directed towards levels of difficulty predetermined by the teacher carry the risk that some students are overtaxed or misjudged or fixed at a specific level as viewed by the teacher. Research shows that learning environments that allow natural differentiation (ND) can reduce these risks (cf. Wittmann, 2001; Scherer & Krauthausen, 2010). Natural differentiation means that the learning environment provided is substantial and complex and offers multiple ways of learning and multiple strategies for solving a given problem.

Consistent with natural differentiation, learning environments allowing own productions or free productions (cf. Streefland, 1990) offer various opportunities for students’ use of their own strategies and provide their own solutions and thus support suitable differentiation. Examples show that especially students with mathematical learning difficulties often make use of the affordances of such environments and show unexpected competencies (e.g., DeBlois, 2014, 2015; Scherer, 1999).

This more open approach brings in specific requirements for the teacher: In general, classroom practice should require more than getting the correct result or being able to perform an algorithm but also explaining and reasoning about solution strategies, and considering solution strategies and associated reasoning. Teachers “need to know how to use pictures or diagrams to represent mathematics concepts and procedures for students, provide students with explanations for common rules and mathematical procedures, and analyze students’ solutions and explanations” (Hill et al., 2005, p. 372).

For a more detailed discussion of the complex field of teacher education—pre-service as well as in-service—teachers’ beliefs, their mathematical and didactical knowledge and the awareness of interactions in classroom see Scherer et al. (2016; also Beswick, 2008; Peltenburg and Van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, 2012).

Conclusions and Perspectives

In this paper various aspects of the situation of students with mathematical learning difficulties have been discussed. The separation of mathematics education and special education has given rise to specific requirements and problems for research which are further complicated by the different conditions in different countries.

Exploring the different ways in which students with mathematics learning difficulties are identified and described in different areas, suggests that many factors can interact to impede the mathematical development of learners and, rather than dichotomising learners into those who experience mathematical learning difficulties and those who do not, it might be more useful to adopt approaches to mathematics education that recognise and value the diversity of learners’ mathematical experiences. This is in contrast to treating differences in learning trajectories as evidence of a deficiency or disorder that necessarily impedes learning or justify segregation. A starting point in constructing a more inclusive mathematics curriculum, therefore, involves envisioning learning scenarios designed to facilitate multiple ways of interacting with mathematical objects, and relationships that respect the diverse experiences (sensory, cognitive, socio-emotional and cultural) and identities of the students with whom we work (Healy et al., 2013). There is need for more evidence-based research in this area.

For teacher education programs, first, it is necessary to distinguish between the needs of teachers and needs of pre-service teachers. For pre-service teachers, there is a need to create situations that help them to distance themselves from their own experiences of learning mathematics as school students (DeBlois & Squalli, 2002). In addition, curriculum, beliefs, personal decompression of mathematical knowledge (Proulx & Bednarz, 2008) and social activities must be discussed in order to manage needs of students with mathematics learning difficulties. The challenge for the teacher is to interpret the events that happen in the classroom in order to make pedagogical and didactical choices (DeBlois, 2006).

In this paper, the focus has mainly been on students, but the challenge of providing a quality mathematics education all goes way beyond the classroom level and involves a rethinking of the institutional structures which mediate both teaching and learning, structures such as curriculum and assessment for example. Experience tells us that it is more efficient to build an accessible building from scratch than to attempt to adapt inaccessible buildings. Can we learn from this as we attempt to build inclusive school mathematics? Perhaps the question is not how we can assist students with mathematical learning difficulties, but how we can learn to build a mathematics education system that no longer disables so many mathematics students.

Notes

- 1.

Network on education systems and policies in Europe http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/index_en.php.

References

Ahmed, A. (1987). Better mathematics. A curriculum development study. London: HMSO.

Ainscow, M. (2013). Developing more equitable education systems: Reflections on a three-year improvement initiative. In V. Farnsworth & Y. Solomon (Eds.), Reframing educational research (pp. 77–89). London: Routledge.

Andersson, U. (2010). Skill development in different components of arithmetic and basic cognitive functions: Findings from a 3-year longitudinal study of children with different types of learning difficulties. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(1), 115–134.

Beswick, K. (2008). Influencing teachers’ beliefs about teaching mathematics for numeracy to students with mathematics learning difficulties. Mathematics Teacher Education and Development, 9, 3–20.

DeBlois, L. (2006). Influence des interprétations des productions des élèves sur les stratégies d’intervention en classe de mathématiques. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 62(3), 307–329.

DeBlois, L. (2014). Le rapport aux savoirs pour établir des relations entre troubles de comportements et difficultés d’apprentissage en mathématiques. Dans Le rapport aux savoirs: Une clé pour analyser les épistémologies enseignantes et les pratiques de la classe. Coordonné par Marie-Claude Bernard, Annie Savard, Chantale Beaucher. http://lel.crires.ulaval.ca/public/le_rapport_aux_savoirs.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2016.

DeBlois, L. (2015). Classroom interactions: Tensions between interpretations and difficulties learning mathematics. Proceedings of the 37th Annual Meeting Canadian Group in Mathematics Education. University of Alberta, Edmonton (Alberta). 171–186. http://www.cmesg.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/CMESG2014.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2016.

DeBlois, L., & Squalli, H. (2002). Implication de l’analyse de productions d’élèves dans la formation des maîtres. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 50(2), 212–237.

Dowker, A. D. (2004). What works for children with mathematical difficulties? London, UK: Department for Children, Schools and Families.

DSM V. (2016). Diagnostical and statistical manual of mental disorders. (5th ed.). http://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm01. Accessed April 13, 2016.

Ellemor-Collins, D., & Wright, R. J. (2007). Assessing pupil knowledge of the sequential structure of number. Educational and Child Psychology, 24(2), 54–63.

Ennemoser, M., & Krajewski, K. (2007). Effekte der Förderung des Teil-Ganzes-Verständnisses bei Erstklässlern mit schwachen Mathematikleistungen. Vierteljahresschrift für Heilpädagogik und ihre Nachbargebiete, 76(3), 228–240.

Ernest, P. (1994). Constructivism: Which form provides the most adequate theory of mathematics learning? Journal für Mathematik-Didaktik, 15(3/4), 327–342.

European Commission (n. d.). Addressing low achievement in mathematics and science. Final Report of the Thematic Working Group on Mathematics, Science and Technology (2010–2013) http://ec.europa.eu/education/policy/strategic-framework/archive/documents/wg-mst-final-report_en.pdf. Accessed June 06, 2016.

Fernandes, S. H. A. A., & Healy, L. (2016). The challenge of constructing an inclusive school mathematics. Paper accepted for presentation in Topic Group 5: Activities for, and research on, students with special needs. 13th International Congress on Mathematics Education, Hamburg.

Francis, D., Fletcher, J. M., Stuebing, K. K., Lyon, R. G., Shaywitz, B. A., & Shaywith, S. E. (2005). Psychometric approaches to the identification of LD: IQ and achievement scores are not sufficient. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 38(2), 98–108.

Fuchs, L. S., Powell, S. R., Seethaler, P. M., Cirino, P. T., Fletcher, J. M., Fuchs, D., et al. (2010). The effects of strategic counting instruction, with and without deliberate practice, on number combination skill among students with mathematics difficulties. Learning and Individual Differences, 20(2), 89–100.

Fuchs, L. S., Powell, S. R., Seethaler, P. M., Cirino, P. T., Fletcher, J. M., Fuchs, D., et al. (2009). Remediating number combination and word problem deficits among students with mathematics difficulties: A randomized control trial. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(3), 561–576.

Gersten, R., Chard, D. J., Jayanthi, M., Baker, S. K., Morphy, O., & Flojo, J. (2009). Mathematics instruction for students with learning disabilities: A meta-analysis of instructional components. Review of Educational Research, 79(3), 1202–1242.

Gervasoni, A., & Lindenskov, L. (2011). Students with “special rights” for mathematics education. In B. Atweh, M. Graven, & P. Valero (Eds.), Mapping equity and quality in mathematics education (pp. 307–324). New York, NY: Springer.

Gifford, S. (2005). Young children’s difficulties in learning mathematics. Review of research in relation to dyscalculia. Qualifications and Curriculum Authority (QCA/05/1545). London, UK: Department for Children, Schools and Families.

Ginsburg, P. H. (1997). Mathematics learning disabilities: A view from developmental psychology. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 30(1), 20–33.

Healy, L., Fernandes, S. H. A. A. & Frant, J. B. (2013). Designing tasks for a more inclusive school mathematics. In Proceedings of ICMI Study 22—Task Design in Mathematics Education (vol. 1, pp. 63–70.). Oxford.

Healy, L., & Powell, A. B. (2013). Understanding and overcoming “Disadvantage” in learning mathematics. In M. A. Clements, A. Bishop, C. Keitel, J. Kilpatrick, & F. Leung (Eds.), Third international handbook of mathematics education (pp. 69–100). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

Hill, H. C., Rowan, B., & Ball, D. (2005). Effects of teachers’ mathematical knowledge for teaching on student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 42(2), 371–406.

Ise, E., Dolle, K., Pixner, S., & Schulte-Körne, G. (2012). Effektive Förderung rechenschwacher Kinder: Eine Metaanalyse. Kindheit und Entwicklung, 21(3), 181–192.

Kaufmann, L., Mazzocco, M. M., Dowker, A., von Aster, M., Göbel, S. M., Grabner, R. H., Henik, A., Jordan, N. C., Karmiloff-Smith, A. D., Kucian, K., Rubinsten, O., Szucs, D., Shalev, R., & Nuerk, H. C. (2013). Dyscalculia from a developmental and differential perspective. Frontiers in Psychology. 4, AUG, Article 516.

Kroesbergen, E. H., & Van Luit, J. E. H. (2003). Mathematical interventions for children with special educational needs. Remedial and Special Education, 24, 97–114.

Maccini, P., Mulcahy, C. A., & Wilson, M. G. (2007). A follow-up of mathematics interventions for secondary students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 22(1), 58–74.

Mazzocco, M. M., & Myers, G. F. (2003). Complexities in identifying and defining mathematics learning disability in the primary school age years. Annals of Dyslexia, 53, 218–253.

Mitchell, D. (2014). What really works in special and inclusive education. Using evidence-based teaching strategies. New York: Routledge.

Moser Opitz, E., Freesemann, O., Grob, U., Prediger, S., Matull, I., & Hußmann, S. (accepted). Remediation for students with mathematics difficulties: An intervention study in middle schools. Journal of Learning Disabilities. doi:10.1177/0022219416668323.

Moser Opitz, E. (2000). Zählen – Zahlbegriff – Rechnen Theoretische Grundlagen und eine empirische untersuchung zum mathematischen erstunterricht in sonderklassen. Bern: Haup.

Murphy, M. M., Mazzocco, M. M., Hanich, L. B., & Early, M. C. (2007). Cognitive characteristics of children with mathematics learning disability (MLD) vary as a function of the cutoff criterion used to define MLD. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 40(5), 458–478.

Pedrotty Bryant, D., Bryant, B. R., Gersten, R., Scammacca, N., & Chavez, M. M. (2008). Mathematics intervention for first- and second-grade students with mathematics difficulties: The effects of Tier 2 intervention delivered as booster lessons. Remedial and Special Education, 29(1), 20–32.

Peltenburg, M., & Van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, M. (2012). Teacher perception of the mathematical potential of students in special education in the Netherlands. European Journal for Special Needs Education, 27(3), 391–407.

Pfister, M., Stöckli, M., Moser Opitz, E., & Pauli, C. (2015). Inklusiven Mathematikunterricht erforschen: Herausforderungen und erste Ergebnisse aus einer Längsschnittstudie. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 43(1), 53–66.

Proulx, J., & Bednarz, N. (2008). The mathematical preparation of secondary mathematics schoolteachers: Critiques, difficulties and future directions. Topics Group 29. ICME 11. Monterrey (Mexico). http://tsg.icme11.org/document/get/83. Accessed 5 May 2016.

Scherer, P. (1999). Entdeckendes Lernen im Mathematikunterricht der Schule für Lernbehinderte—Theoretische Grundlegung und evaluierte unterrichtspraktische Erprobung (2nd ed.). Heidelberg: Edition Schindele.

Scherer, P. (2003). Different students solving the same problems—the same students solving different problems. Tijdschrift voor Nascholing en Onderzoek van het Reken-Wiskundeonderwijs, 22(2), 11–20.

Scherer, P., Beswick, K., DeBlois, L., Healy, L., & Moser Opitz, E. (2016). Assistance of students with mathematical learning difficulties: How can research support practice? ZDM—Mathematics Education, 48(5), 633–649.

Scherer, P., & Krauthausen, G. (2010). Natural differentiation in mathematics—the NaDiMa project. Panama-Post, 29(3), 14–26.

Scherer, P., & Moser Opitz, E. (2010). Fördern im Mathematikunterricht der Primarstufe. Heidelberg: Springer.

Skovsmose, O. (2015). Inclusion: A contested concept. In: Anais do VI Seminário Internacional de Pesquisa em Educação Matemática—VI SIPEM, Pirenópolis, Goiás, Brasil.

Streefland, L. (1990). Free productions in learning and teaching mathematics. In K. Gravemeijer, M. van den Heuvel, & L. Streefland (Eds.), Contexts free productions tests and geometry in realistic mathematics education (pp. 33–52). Utrecht: Freudenthal Institute.

Streefland, L., & Treffers, A. (1990). Produktiver Rechen-Mathematik-Unterricht. Journal für Mathematik-Didaktik, 11(4), 297–322.

Trickett, L., & Sulke, F. (1988). Low attainers can do mathematics. In D. Pimm (Ed.), Mathematics, teachers and children (pp. 109–117). London: Hodder and Stoughton.

UNESCO International Bureau of Education. (2009). Inclusive education: The way of the future. In International Conference on Education, 28th Session, Geneva, UNESCO Paris, November 25–28, 2008. Retrieved from http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Policy_Dialogue/48th_ICE/ICE_FINAL_REPORT_eng.pdf

Van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, M. (1991). Ratio in special education. A pilot study on the possibilities of shifting the boundaries. In L. Streefland (Ed.), Realistic Mathematics Education in Primary School. On the occasion of the opening of the Freudenthal Institute (pp. 157–181). Utrecht: Freudenthal Institute.

Von Glasersfeld, E. (1995). A constructivist approach to teaching. In L. P. Steffe & J. Gale (Eds.), Constructivism in education (pp. 3–15). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

WHO—World Health Organisation. (2016). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en#/F81.9. Accessed April 13, 2016.

Wißmann, J., Heine, A., Handl, P., & Jacobs, A. M. (2013). Förderung von Kindern mit isolierter Rechenschwäche und kombinierter Rechen- und Leseschwäche: Evaluation eines numerischen Förderprogramms für Grundschüler. Lernen und Lernstörungen, 2(2), 91–109.

Wittmann, E. C. (2001). Developing mathematics education in a systemic process. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 48(1), 1–20.

Woodward, J., & Brown, C. (2006). Meeting the curricular needs of academically low-achieving students in middle grade mathematics. The Journal of Special Education, 40(3), 151–159.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access Except where otherwise noted, this chapter is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

Scherer, P., Beswick, K., DeBlois, L., Healy, L., Moser Opitz, E. (2017). Assistance of Students with Mathematical Learning Difficulties—How Can Research Support Practice?—A Summary. In: Kaiser, G. (eds) Proceedings of the 13th International Congress on Mathematical Education. ICME-13 Monographs. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62597-3_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-62597-3_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-62596-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-62597-3

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)