Abstract

Research on bullying and harassment in Scandinavia has been going on for several decades, and is appearing in new frameworks and forms since the new categories of “cyber-harassment” or “cyber-bullying” have been introduced. Bullying is a phenomenon of great worry, as it seems to affect children and adolescents both on short and long term. A questionnaire on cyber-harassment was designed in this study, and answered by pupils and their parents and teachers, at five schools in the city of Tromsø, Norway. The questionnaire included a section of questions concerning traditional forms of harassment and bullying, as well as questions on quality of life (QoL), and the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). The main research questions were: (1) What is the prevalence of the three classical types of bullying and cyberbullying; (2) Are there gender or age differences; (3) What percentage of children bullied classically were also cyberbullied; (4) How and to what extend did those that were bullied also suffer a lower quality of life. The main novel contribution of this study to the ongoing research is that students who reported being cyber-harassed or cyberbullied, also reported significantly lower QoL-scores than their non-harassed peers.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

It is widely acknowledged that children’s experience on transactions with peers play an important part in children’s development and socialization (Hartup 1978; Harris 1998; Scarr 1992). Perceived positive relations with others are associated with the enhancement of social understanding (Dunn 1999) and social competency and positive adaptation in childhood and in school (Hartup 1983), but also with positive adaptation later on in life (Hartup 1976; Parker and Asher 1987). Parker and Asher (1987) found evidence of the fact that children experiencing poor adjustment with others were at high risk of developing serious problems in adulthood. Thus, experienced relationships to others in school are of fundamental importance for positive or poor adaptation later on in life.

1.1 Bullying and Harassment

Bullying of other children or being a victim of bullying have repeatedly been documented to exert negative influence on children’s development with serious long-term effects. In a large comparative study on the prevalence of bullying in various western countries involving 123,227 students aged 11, 13 and 15 uncovered the following: the lowest prevalence of bullying or being bullied was reported by Swedish girls (6.3%), while the highest came from boys in Lithuania (41.4%). Generally, girls were less involved in bullying compared with boys (Due et al. 2005). In a study from northern Norway involving 4167 girls and boys from 66 schools, about 5% reported being bullied (Rønning et al. 2004). Most of these were boys.

Olweus (1999) defines bullying as a situation when a child/student repeatedly experience negative reactions over time from one or more fellow students who intentionally apply these reactions and where the victim cannot defend him-/herself. Bullying is often divided into four categories: (i) direct/physical (physical attack or theft); (ii) direct verbal (threats, insults, calling names); (iii) indirect/relational (social exclusion, spreading of nasty rumors) and (iv) cyber bullying (text messages, posting pictures, spreading rumors, exclusion from social media like Facebook). Cyber bullying is a new phenomenon. Thus, knowledge of its prevalence and short and long-term effects is scarce. However, research on cyber bullying is increasing (Slonje and Smith 2008; Smith et al. 2006). Most studies report its prevalence and correlate to classical bullying. In this project we will report on all types of bullying and also relate them to the perceived quality of life and mental health.

Research (Frisén et al. 2008; Rønning et al. 2009; Smith 2002; Ybarra et al. 2012) has uncovered uncertainty about the definition of bullying and there is a disagreement between parents, teachers and children about its prevalence, and thus it’s prevention. With the introduction of cyber bullying, Slonje and Smith (2008) argue for a debate on the criteria for something to be called bullying. The debate is especially focused on the criteria for repetition. As an example, they discuss the event of posting of unpleasant pictures on the web. Even though only one picture is posted, many might see it, and it may stay on the web for a long time. Thus, it seems imperative to continue to conduct both qualitative and quantitative studies on how students, teachers and parents define bullying, improve the measurement of bullying and study both short and long-term effects of bullying on well-being.

1.2 Mental Health

To experience being bullied over a long time is considered to be one of the most stressful life events (Branwhite 1994), and those experiencing this are placed in a high-risk position regarding the development of a negative self-image and poor adaptation (Deković and Gerris 1994). It has also been uncovered that children bullying other children are more at risk of later psychiatric problems and criminality than their victims are (Kumpulainen and Raesaenen 2000; Sourander et al. 2007a, b). For example, Sourander et al. (2007a, b) uncovered that 28% of the boys in a representative sample of boys born in 1981 who were reported being bullies or bully-victims in the age of 8 years, had a psychiatric diagnosis 10 years later. Altogether 33% of these boys were found in the Finnish criminal registry when they were 16–20 years of age. However, this was relevant only for those boys reporting psychiatric symptoms when they were 8 years old. Thus, an early combination of bullying behavior and psychiatric problems is a very strong predictor/factor indicating later psychiatric disorders and criminality. A study in Norway (Rønning et al. 2004) found strong associations between being a victim and problems with friends and behavior problems. Another study (Salmon et al. 2000) found that victims were referred to mental health services due to depression and generalized anxiety, whereas bullies were referred because of behavior problems and ADHD.

Several studies have shown associations between problematic child – child relationships and later criminality (Roff et al. 1972), school refusal (Parker and Asher 1987), military records with serious behavior problems (Roff 1961), manic-depressive and schizophrenic disorders (Cowen et al. 1973; Kohn and Clausen 1955) and suicide (Stengel 1971). These problems have also been associated with parental problems like poverty, substance abuse, psychiatric problems, and child neuropsychological problems. All studies mentioned here have focused on the relationship between mental health and classical bullying. So far, we know very little about the relationship between cyber bullying and mental health.

1.3 The School Culture

The bystanders of bullying may have an essential influence on bullying. It has been uncovered that other students have been involved in 85% of bullying episodes, either as observers or as direct participants (Craig and Pepler 1995, 1997). In particular Salmivalli and associates (2004) have documented that bullying is reinforced by fellow students. This may lead to such behavior being regarded as acceptable and normative within the peer group. It is speculated that the main reason for the poor effect of anti-bullying programs is lack of understanding of the importance of the school culture (Swearer et al. 2009).

1.4 Quality of Life

Both bullying and victimization are associated with the experience of poor quality of life (Thorvaldsen et al. 2016). Quality of life is the individual’s experience of life being satisfactory. Quality of life is a multidimensional concept, which includes physical and emotional well-being, self-image, relationships within family and amongst friends and the daily functioning in school. Jozefiak et al. (2008) investigated the perceived quality of life (KINDL-r) of 1997 randomly selected students aged 8–16 in the middle of Norway (participation 71.2%) The study uncovered acceptable psychometric properties of the instrument; the children scored themselves lower than the parents, and girls lower than boys. This study will constitute a reference in the present study.

1.5 Research Questions

The main research questions in this study were: What is the prevalence of various types of bullying, and what are the associations to mental health and quality of life? Examples of various questions to be answered are the following:

-

1.

What are the percentage of bullies, bully-victims, victims and bystanders?

-

2.

Are those related to cyber bullying the same as those related to classical bullying?

-

3.

What characterizes the various bullying types?

-

4.

What is the relationship between the students’ well-being and their functioning in school?

-

5.

How is the mental health of students in the study?

-

6.

How do the students in the study perceive their quality of life?

-

7.

How do bullying influence the mental health and adaptation in school?

-

8.

Are there changes in the pattern of experienced peer relationships and mental health and quality of life across time?

In addition to these quantitative problems, it was of interest to collect qualitative data in order to better understand the school culture. Because the teacher education in Tromsø has been integrated into the University of Tromsø and became a Master’s degree program, involvement of students in answering research questions is an integrated aim of the project.

2 Methods

2.1 Design

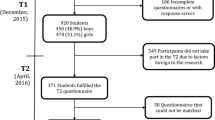

The study was designed both as a prospective longitudinal and as a cross-sectional time trend study starting in late fall 2013. In the prospective longitudinal part of the study, the same students will be followed for a period of up to 6 years. The long term study is still ongoing, as shown in Fig. 19.1.

2.2 Participants

A pilot project was carried out at one of the teacher training schools in order to establish the most effective logistics. The aim of the formal project was to include five teacher training schools (grade 4–10) a total number of ~1000 children/students (50% girls). These children will be followed up with the same questionnaires every year for a period of 6 years as a time trend study. The child/student, teacher and parents constitute the informants. On the perceived quality of life questionnaire (KINDLE-r) only the student and parents constitute the informants. It is of uttermost importance that the research project connects the researcher, student, teacher and parents and thus promotes the research and research-based knowledge in the education of teachers.

2.3 Instruments

Demographics

A questionnaire asking for gender, about parents’ occupations, and how many years of education they have was applied.

Classical Harassment

Classical harassment was divided into three categories: “physical aggression” – 4 questions; “verbal harassment” – 5 questions; and “social manipulation” – 6 questions. These categories and questions are derived from the study of Rønning et al. (2004). The instrument demonstrated very good psychometric properties.

Cyber Harassment

This part of the investigation builds on questionnaires developed by Smith et al. (2006) and Menesini el al. (2011). In the investigation it was asked how often participants have experienced cyber bullying during the last 2–3 months in the different areas of mobile phone and internet. The first questions are general about prevalence when they attended school and outside school, and to what degree the student had participated in the bullying. It was followed up with a series of questions covering ten types of cyber bullying (SMS, MMS, phone calls, e-mail, internet text, instant messages, chat, blogs, internet video, and exclusion from social media like Facebook).

A five point Likert scale was applied on all types of bullying (never, only once or twice, two or three times a month, about once a week, many times per week). It was also asked what reactions they had received when bullying is alerted, and to what degree the students themselves and the teacher tried to stop it.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

SDQ is a screening instrument for behavioral and emotional problems that consists of 25 questions distributed equally on the following dimensions: “emotional symptoms”, “behavior problems”, “hyperactivity”, “problems with friends” and “pro-social behavior”. A “total problem score” is calculated (Goodman 1997). The SDQ comes in different versions for children of different age, teachers and parents.

Quality of Life (KINDL-r)

KINDL-r measures perceived quality of life (Ravens-Siberer and Bullinger 2000). There were two versions; one where the parents evaluate the child, and one where the child evaluates own quality of life. Every version consists of 24 questions. Each question asked for the last week experiences, and was scored on a 5-point scale (“never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “often”, “always”). The psychometric properties of KINDL-r are considered as very good (Jozefiak et al. 2008), but for the Norwegian version more validation work is requested.

2.4 Ethics

The study was carried out digitally using the commercial online survey tool “Questback”. Only the project leadership of the University of Tromsø had access to the filled-in questionnaires. For student’s inclusion to the study, the parents must have given their signed informed consent. Students and parents were able to resign at any time from the study without grounds, and data that have not already been published will be deleted. A separate consent regarding those participating in the interview part of the study will be obtained.

Feedback to schools was submitted through annual dialog conferences, and each school received a report where it can be compared with the gross mean. If wanted, each school will also receive a report where data from each class was published. The project was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee for Medical Research (REK-Nord).

3 First Results from the Study

Pilot Study

The design, administration and the questionnaire of the project was tested out at one pilot school in 2012/2013. Analyses from the pilot study revealed several interesting results. There were differences on how students reported being bullied. Low occurrence was reported when asked how often they are being bullied, but at the same time, the students report higher frequencies of concrete harassment actions. In other words, they reported that they were not being bullied, but still they were quite often exposed to name-calling, teasing and various forms of negative physical actions. In addition, students at grade 7–9 reported significantly lower bullying than at younger grade (4–6). Monks and Smith (2006) point out that age is a factor how they define bullying. Older children (age 14) normally demonstrate a more differentiated understanding while the younger ones (age 6–8) often relate bullying to physical aggression. This is in line with other reports on this issue. Boulton et al. (2002) find that children do not necessarily regard social exclusion, name-calling and stealing as bullying, whereas the physical categories are more often defined as bullying by the children.

Long-Term Study

Some results from the first year of the study are recently reported in Thorvaldsen et al. (2016), and in Egeberg et al. (2016). It was found that, compared to traditional bullying, cyberbullying is less common, but it now affects some 3.5% of pupils, i.e. more than one third of the level of classical bullying, and most of it takes place outside of school. There are only small gender-related differences in incidence at both primary school (ages 10–13) and secondary school (ages 14–16), contrary to many earlier research reports.

Both “traditional” and cyber forms of bullying and harassment show significantly (p < 0.05) lower scores on their self-perceived quality of life factors. Non-victims reported a mean between 4.1 and 3.4 on a scale from 1 to 5, while those who reported having been bullied reported a mean between 3.7 and 3.0. Cyber-harassment and cyber-bullying share the same negative characteristics in relation to quality of life as classical harassment and bullying. Using Structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses, it was found that both cyber harassment and cyber bullying had a distinct and substantial impact on students’ academic achievements. However, this effect was largely mediated through a reduction in students’ perceptions of quality of life. Thus, it is important to address the issue of perceived quality of life, especially for those students being subjects to bullying and severe harassment.

To elaborate more about these issues and on how students perceive the term “bullying”, focus group interviews with students and with teachers were conducted. In the various interviews, the general term and the specific categories, and age variations (Egeberg et al. in press) of bullying were examined. Furthermore, the issues of perceived severity in specific negative conduct and point at differences between teachers and students were addressed in this regard.

4 Concluding Remarks

In order to determine whether the results obtained from this study are stable over time, and to produce a more detailed study of causalities between the variables, a longitudinal study is necessary, and this project will accomplish that in the near future (Fig. 19.1). The results obtained from long-term studies like this one may lead to a deeper understanding of student relations, and the development of much-needed policy and methods of preventing and intervening in cases of harassment and bullying.

References

Boulton MJ, Trueman M, Flemington I (2002) Associations between secondary school pupils’ definitions of bullying, attitudes towards bullying and tendencies to engage in bullying: age and sex differences. Educ Stud 28(4):353–370

Branwhite T (1994) Bullying and student distress: beneath the tip of the iceberg. Educ Psychol 14(1):59–71

Cowen EL, Pederson A, Babigian H, Izzo LD, Trost MA (1973) Long-term follow-up of early detected vulnerable children. J Consult Clin Psychol 41:438–446

Craig WM, Pepler DJ (1995) Peer processes in bullying and victimization. An observational study. Except Educ Can 5:81–95

Craig WM, Pepler DJ (1997) Observations of bullying and victimization in the school yard. Can J Sch Psychol 13:41–59

Deković M, Gerris JRM (1994) Developmental analysis of social cognitive and behavioral differences between popular and rejected children. J Appl Dev Psychol 15:367–386

Due P, Holstein BE, Lynch J et al (2005) The health behaviour in school-aged children bully working group. Bullying and symptoms among school-aged children: international comparative cross sectional study in 28 countries. Eur J Pub Health 15:128–132

Dunn J (1999) Siblings, friends, and the development of social understanding. In: Collins AW, Lauritsen B (eds) Relationships as developmental contexts. The Minnesota symposia on child psychology, vol 30. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New York, pp 263–279

Egeberg G, Thorvaldsen S, Rønning JA (2016) The impact of cyberbullying and cyber harassment on academic achievement. In: Digital expectations and experiences in education. Sense Publishers, Rotterdam, pp 183–204

Egeberg G, Thorvaldsen S, Rønning JA (Manuscript in press) Understanding bullying: how students and their teachers perceive terms of negative conduct

Frisén A, Holmqvist K, Oscarsson D (2008) 13-year-olds’ perception of bullying: definitions, reasons for victimisation and experience of adults’ response. Educ Stud 34(2):105–117

Goodman R (1997) The strenghts and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38:581–586

Hartup WW (1976) Peer interaction and behavioral development of the individual child. In: Schopler E, Reichler RJ (eds) Psychopathology and child development. Plenum Press, New York

Hartup WW (1978) Children and their friends. In: McGurk H (ed) Issues in childhood social development. Methuen, London, pp 130–170

Hartup WW (1983) Peer relations. In: Mussen P (series ed) & Hetherington E (vol ed), Handbook of Child Psychology, (vol 4): Socialization, personality and social development. Wiley, New York, pp 103–198

Harris JR (1998) The nurture assumption. Why children turn out the way they do. Parents matter less than you think and peers matter more. The Free Press, New York

Jozefiak T, Larsson B, Wichstrøm L, Mattejat F, Ravens-Sieber U (2008) Quality of life as reported by school children and their parents: a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 6:34

Kohn M, Clausen J (1955) Social isolation and schizophrenia. Am Sociol Rev 20:265–273

Kumpulainen K, Raesaenen E (2000) Children involved in bullying at elementary school age: their psychiatric symptoms and deviance in adolescence. An epidemiological sample. Child Abuse Negl 24:1567–1577

Menesini E, Nocentini A, Calussi P (2011) The measurement of cyberbullying: dimensional structure and relative item severity and discrimination. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 14(5):267–274

Monks CP, Smith PK (2006) Definitions of ‘bullying’; age differences in understanding of the term, and the role of experience. Br J Dev Psychol 24:801–821

Olweus, D. (1999). In: Smith PK, Morita Y, Junger-Tas J, Olweus D, Catalana R, & Slee P. (eds) The nature of school bullying. A cross-national perspective. Routledge, New York

Parker JG, Asher SR (1987) Peer relations and later personal adjustment: are low-accepted children at risk? Psychol Bull 102:357–389

Ravens-Siberer U, Bullinger M (2000) KINDL-R Questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life in children and adolescents – revised version 2000 (http://www.kindl.org)

Roff M (1961) Childhood social interactions and adult bad conduct. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 63:333–374

Roff M, Sells B, Golden MM (1972) Social adjustment and personality development in children. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis

Rønning JA, Handegård BH, Sourander A (2004) Self-perceived peer harassment in a community of Norwegian school children. Child Abuse Negl 28(10):1067–1079

Rønning JA, Sourander A, Kumpulainen K et al (2009) Cross-informant agreement about bullying and victimization among eight-year-olds: whose information best predicts psychiatric caseness 10–15 years later? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 44:15–22

Salmivalli C, Voeten M (2004) Connections between attitudes, group norms and behavior associated with bullying in schools. Int J Behav Dev 28:246–258

Scarr S (1992) Developmental theories for the 1990’s: development and individual differences. Child Dev 63:1–19

Salmon G, James A, Cassidy EL, Javaloyes AM (2000) Bullying a review: presentations to an adolescent psychiatric service and within a school for emotionally and behaviorally disturbed children. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 5:563–579

Slonje R, Smith PK (2008) Cyberbullying: another main type of bullying? Scand J Psychol 49(2):147–154

Smith PKP (2002) Definitions of bullying: a comparison of terms used, and age and gender differences, in a fourteen-country international comparison. Child Dev 73(4):1119–1133

Smith PK, Mahdavi J, Carvalho M, Tippett N (2006) An investigation into cyberbullying, its forms, awareness and impact, and the relationship between age and gender in cyberbullying, Research brief no RBX03-06. DfES, London

Sourander A, Jensen P, Rønning JA et al (2007a) What is the early adulthood outcome of boys who bully or are bullied in childhood? The Finnish “From a boy to a man” study. Pediatrics 120:397–404

Sourander A, Jensen P, Rønning JA et al (2007b) Are childhood bullies and victims at risk of criminality in late adolescence? The Finnish “From a boy to a man” study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161:546–552

Stengel E (1971) Suicide and attempted suicide. Penguin, Middelsex

Swearer SM, Espelage DL, Napolitano SA (2009) Bullying prevention and intervention: realistic strategies for schools. Guilford, New York

Thorvaldsen S, Stenseth AM, Egeberg G, Pettersen GO, Rønning JA (2016) Cyber harassment and quality of life. In: Digital expectations and experiences in education. Sense Publishers, Rotterdam, pp 161–182

Ybarra ML, Boyd D, Korchmaros JD, Oppenheim JK (2012) Defining and measuring cyberbullying within the larger context of bullying victimiza-tion. J Adolesc Health 51(1):53–58. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.031

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Rønning, J.A., Thorvaldsen, S., Egeberg, G. (2017). Well-Being in an Arctic City. Designing a Longitudinal Study on Student Relationships and Perceived Quality of Life. In: Latola, K., Savela, H. (eds) The Interconnected Arctic — UArctic Congress 2016. Springer Polar Sciences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57532-2_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57532-2_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-57531-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-57532-2

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)