Abstract

This chapter provides an analysis of structural transformations of the Lithuanian higher education landscape paying special attention to developments during Soviet times and in the period after 1990. Lithuanian higher education, which dates back to the sixteenth century, has changed from a traditional elite system to a mass system over time. Political, economic and social change, including the Soviet occupation of the country, the re-establishment of independence and Europeanization through the Bologna Process and accession to the European Union have had significant impact on the Lithuanian higher education landscape.

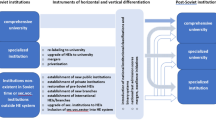

We have identified three periods of structural change. The first period from 1990 to 2000 is characterized by the re-establishment of universities and of academic autonomy and sporadic expansion of the system. During the second phase from 2001 to 2009, main system expansion and horizontal differentiation took place due to the establishment of the private higher education sector and a boom of the non-university higher education sector. Further, vertical differentiation within the system was reinforced through the availability of EU funding. The third phase, which started in 2010, has witnessed demographic decline, increasing competition and efforts of internationalization as well as more recently also attempts at consolidation of HEIs. The major challenges for the future of this system lie in increasing trust in public authorities, breaking from path dependencies of Soviet legacy, demographic changes, brain drain and increasing competition.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of transformation of the higher education landscape in post-Soviet Lithuania. Our special focus is on the vertical and horizontal system differentiation in an attempt to explain the main forces leading to such system dynamics. Lithuanian higher education has changed from an elite system with one flagship university towards a mass system with various institutions—both of university and non-university type. Vertical differentiation exists in terms of private higher education providers, regional providers as well as alliances between universities both on a national and international scale. Much of this differentiation was brought by political, economic and social changes, including the Soviet occupation of the country, the re-establishment of Lithuanian independence, the signing of the Bologna Declaration and the accession to the EU. Besides, a set of higher education reforms revealed the state’s ambition to boost higher education quality and to ensure access to higher education to various segments of population.

Emergence of the Higher Education System in Lithuania

Lithuanian Higher Education Before 1940

Lithuania has had a long-lived tradition of elite higher education. One of the oldest universities in Europe, Vilnius University, was established in the country’s capital in 1579. Yet, Lithuania’s turbulent history and political developments, on the one hand, and the nature of the industrialization and the dominance of agricultural sector in the country, on the other hand, had a significant impact on the development of the higher education system. Under the rule of the Russian Tsar, Vilnius University was shut down for almost a century from 1831 until 1919 and the Lithuanian language was banned. Lithuania regained independence in 1918, which led to the most important period for establishment and development of general, vocational and higher education in the country. New specialized professional training institutions, both regional and national, were central to the development of the Lithuanian nation state and were fostering Lithuanian culture, language and economy. After the end of World War I in 1918, Vilnius and the region surrounding it were annexed by Poland, but Vilnius University continued to function on Polish territory as Stefan Batory University until 1939. Therefore, a new ‘University of Lithuania’ (later named Vytautas Magnus University, VMU) was established in Lithuania’s interim capital, Kaunas (Bumblauskas et al. 2004; Mašiotas 1923).

By 1940, the time of the Soviet annexation, Lithuania had the following institutions of higher education: Vilnius University (VU, which became Lithuanian after the territory of Vilnius was returned to Lithuania in 1939), the Vilnius Art School (established in 1940 on the basis of an VU department), the Vytautas Magnus University (established as the University of Lithuania in 1922 in Kaunas), the Agricultural Academy (1924, Dotnuva), the Conservatoire of Kaunas (1933), the Institute of Commerce (1934, Klaipėda, 1939–1944 in Šiauliai), the National Pedagogical Institute (1935, Klaipėda), the Veterinary Academy (1936, Kaunas) and the Kaunas Art School (1922, renamed the Kaunas School of Applied Arts in 1940) (OECD 2002; Leišytė 2002).

Lithuanian Higher Education During the Soviet Period (1940–1941 and 1944–1990)

Based on a political agreement between the Soviet and German governments, the Baltic States became part of the Soviet Union in June 1940. Although the first period of Soviet control over Lithuania lasted only 1 year (1940–1941), it was the time when a formal restructuring of the Lithuanian higher education system based on the Soviet standards commenced (Procuta 1967; Šakalys 1985). Vytautas Magnus University lost its Faculties of Theology and Philosophy. Many academics were relieved from their duties, and those engaged in intellectual resistance were arrested and sent to Siberian Gulags (OECD 2002; Zulumskytė 2014, 118; Leišytė 2002; KTU 2016b; VMU 2016). Teaching and research activities were separated into different institutional settings with the establishment of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences. After the end of WWII, the higher education sector was redesigned according to the Soviet model and became subject to Moscow’s centralized control (Leišytė 2002). Vytautas Magnus University was closed in 1950, and its medical and technological faculties were re-established as independent institutes. However, many other higher education institutions that had existed before the war were re-opened and new faculties covering the Soviet agricultural and industrial needs were founded. A restructured Lithuanian higher education, which followed the Soviet model of higher education, was achieved by the mid-1950s and specialized institutions in the main cities and their subsidiaries in the regions performed the major task of preparing teachers, engineers and doctors for the Soviet-industrialized economy (Šakalys 1985). Universities, which traditionally acted as centres of teaching and research according to a Humboldtian model, were thus redefined as centres for professional training, and academic freedom and autonomy were eliminated, while the curriculum was controlled by the state (Suchodolski 1971; Želvys 2004). The goal of higher education was mainly focused on polytechnic education and training the ‘socialist man’, and the traditions of Lithuanian higher education aimed at educating Lithuanian citizens according to Christian values were eradicated (Leišytė 2002). Despite this, Lithuanian remained the main language of instruction (ibid.) (Fig. 11.1).

In Lithuania, industrialization was not as rapid and heavy compared to Estonia and Latvia (Willerton 1992). In the 1960s, however, industrialization in Lithuania started to pick up in the regions, which triggered the geographical spread of some of the higher education institutions. For example, to cater for the needs of electrical and mechanical engineering in the north of the country, which hosted a Soviet military airport, key factories producing electronics, as well as bicycles and naval engineering in the west of the country, Kaunas Technology Institute faculties or extramural programmes were established in the cities of Panevėžys, Šiauliai and Klaipėda. Thus, we can observe some horizontal differentiation in this period.

By the end of the Soviet era in 1989, the Lithuanian higher education system consisted of one university (Vilnius University, centrally funded from Moscow to prepare the academic and party elites), one music conservatory, five institutes, four academies and one Higher Party School. VMU, which was a symbol of independent Lithuania and its intellectual elite, was destroyed. The role of the state was severely interventional. All processes, including core academic activities, were controlled by the Ministries of Education either in Vilnius or in Moscow. Higher education in the Soviet period was free, while access to higher education was based on merits for the Communist party, affiliation to it being an important requirement. By 1990, the gross enrolment ratio in higher education was 33.25%, which is slightly higher than in the other Baltic states at that time: to compare, Estonia (24.75%) and Latvia (24.87%).

Lithuanian Higher Education in 1990

The Lithuanian higher education landscape in 1990 inherited the legacy of a diversified system from the Soviet period and pre-WWII Lithuania. In contrast to many other Soviet republics, Lithuania had already begun to act independently from the Soviet Union prior to its official dissolution in 1990. In the 1980s under the policy of glasnost, Lithuanian democracy movements started to weaken the Soviet institutional base of government establishments. It served as a foundation for and laying the basis for the new higher education system (OECD 2002). The first step towards transformation of the Soviet model of higher education in Lithuania took place in 1989–1990, when Vytautas Magnus University (VMU) in Kaunas was re-established. It was supported by Lithuanian expats who returned to their fatherland at that time, predominately from the USA and Canada. The institution was designed as a liberal arts university, adopted the US-American academic degree system with bachelor’s and master’s degrees and offered programmes in English. As such, the re-establishment of VMU was a symbol for both the imminent breakdown of the Soviet Union and the profound changes that would occur within the Lithuanian higher education system in the years to come. At that time, in 1989, many higher education establishments already prepared the new statutes (OECD 2002).

The first and most significant political step towards the restructuring of the Lithuanian higher education sector was to reform the higher education legal basis. The Constitution of Lithuania ensured the autonomy of universities and free higher education for qualified students. The first enacted laws were the Law of the Republic of Lithuania concerning the Approval of the Status of Vilnius University (1990), the Framework Law on Education and the Law on Higher Education and Science (LHE) (1991). The most important aspect for higher education institutions in Lithuania was to clear themselves from Soviet ideology and become autonomous from the state. The 1991 LHE defined the governance, autonomy and financing of higher education institutions in broad terms and showed confidence regarding quality and academic freedom of academics in Lithuania (OECD 2002). It allowed specialized institutes, which were preparing students for certain professions (such as medicine or engineering) to be renamed into universities or academies. In this way, the Academy of Music and Vilnius Art Academy were born. This trend of seeking prestige and rebranding into universities or academies was also noted as ‘universification’ (Želvys 2004), as it was rather obvious that the trend of relabelling the institutions could enhance their prestige. It also allowed some institutions to be ‘upgraded’ into universities, such as the former police professional school, which was reorganized into a university in Vilnius (Mykolas Romeris University at present). Regional institutes and technical colleges (‘technicums’) also took the chance to upgrade themselves. That is how two regional universities were created: Šiauliai University (based on former Pedagogical Institute and pre-war Commerce School moved from Klaipėda) and Klaipeda University (which had three faculties: Humanities and Education, Marine Technology, Social and Health Sciences). Further horizontal differentiation was allowed as the first private institutions appeared, although they were not officially recognized as part of the higher education sector until 2000. Another important development in 1990 in terms of horizontal differentiation was the establishment of religious higher education institutions, as well as Lithuanian Military Academy. These were institutions that embodied the economic, political and academic freedoms Lithuania regained: for instance, the military training was no longer taking place in Russia or Ukraine, at the bases for the Soviet Army, but in Lithuania for the Lithuanian Army. Lithuania, being a predominantly Catholic country, also got an opportunity to profess its religion, which meant that apart from the Catholic Seminary in Kaunas, Telšiai and Vilnius Seminaries were opened.

Thus, the preconditions for promoting the geographical spread of higher education institutions and horizontal differentiation were created in 1991 with the enactment of the first regulatory frameworks. At the same time, the system experienced chronic underfunding, low wages, high inflation and decreasing quality, although still having the features of elite higher education (with only 50,000 students in the system of 3.7 million population of Lithuania in 1990). The task of governing higher education institutions was given to a newly created Department for Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Lithuania and the government of Lithuania. The following table presents a typology of institutions in 1990 (Table 11.1).

Policy Developments and Other Factors Influencing Structural Change in Lithuanian Higher Education After 1990

Since 1990, significant changes have taken place within the Lithuanian higher education system in terms of horizontal and vertical differentiation as well as inter-organizational collaborations (Leišytė and Kiznienė 2006; Leišytė et al. 2015; Želvys 2004). The main advances of higher education transformation included system expansion in terms of the amount and types of higher education institutions, as well as the number of students, the creation of binary higher education system, the agglomeration of research institutes into universities and the mergers of faculties and institutions. These developments were partly caused by increasing competition between institutions, changes in funding models of higher education, demographic downturn and immigration partly facilitated by access to Western European higher education markets and academic mobility due to EU membership. Changes were brought about by incremental legislative changes (Laws on Science and Higher Education, 1991, 2000 and 2009), numerous bylaws, as well as constant policy developments related to the Europeanization of the system (Bologna Process, EU accession, EU Structural Funds availability), international donor influences (the World Bank, Nordic Council of Ministers, Soros Foundation in Lithuania), transformation of the academic system after the collapse of the Soviet Union (dismantling the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences research institutes), and the collapse of certain industries and a consequent lack of demand for certain graduates and certain types of research. In the following sections, we provide a policy development account during the main three periods of structural change of the system: 1990–2000, 2001–2009, 2010 to present.

Years 1990–2000: Regained Autonomy and Sporadic Expansion

The main changes in the Lithuanian higher education sector in the early 1990s were rather sporadic and focused on renaming and ‘re-establishment’ of universities and academies. The foundation of two regional universities followed the logic of regional revival, because due to the economic downturn, regional authorities were pressing for ‘having university in their city’. At the same time, the former technical institutes in Kaunas and Vilnius, which were training engineers and architects for the Soviet economy, were rebranded into Technology universities (in this way Kaunas University of Technology and Vilnius Gediminas Technical University were created). While in 1989, the majority of students in Central and Eastern European countries studied natural sciences and engineering, the 1990s saw a decrease in these fields and an increasing demand for programmes in the humanities and the social sciences (Scott 2015). As a consequence, some universities in Lithuania, such as Kaunas University of Technology, expanded their profiles by adding the social sciences and the humanities in order to absorb large numbers of fee-paying students, especially in management and business, as well as humanities.

In 1991, universities in Lithuania were granted a high degree of autonomy to relinquish the Soviet political grip on higher education. The Law on Science and Higher Education (1991) defined the boundaries of state regulation (Leišytė 2002). The two instruments which remained at the state’s disposal were the funding of higher education as well as the demand for certain type and number of graduates. The governmental bodies controlling universities were dispersed, which allowed a sporadic expansion of the system and led to chronic underfunding. This was soon compensated by the introduction of tuition fees (a merit-based system was established, where a certain number of study places at the entrance to higher education were state funded, while others could enter the university, but had to pay). From the mid-1990s onwards, student numbers started to increase substantially, as did the share of fee-paying students, which changed from 3.5% in 1995–1996 to 33.1% in 2000–2001. Universities started to compete for students, as they were bringing in extra cash. Due to sporadic expansion, the quality of higher education was deteriorating. As international support from the PHARE programme, the Council of Europe and foreign donors started coming in, the Centre for Quality Assessment in Higher Education was established in 1995 to ensure the quality as well as to accredit the study programmes (ibid.). The Centre also took over the role of recognizing foreign degrees, as this became a necessity due to increasing outgoing mobility of students. This development indirectly showed that the state was coming back into the game of supervising higher education sector and monitoring via intermediary agency.

The funding of foreign donors was highly important for the process of re-establishment and change not only in terms of global structural landscape but also for introducing institutional changes. Based on the US system, bachelor (4 years) and master’s (2 years) system was foreseen in study programmes of universities since 1991. In contrast to Soviet times, universities were expected to carry out research and grant doctoral degrees again, which increased their power vis-à-vis other higher education institutions and called for the implementation of a stronger teaching-research nexus than before. The governance of higher education in the 1990s was carried out between university rectors and the Department for Science and Higher Education (which was later incorporated into the Ministry of Education and Science of Lithuania) (ibid.). The Lithuanian Science Council acted as an advisory body, while the Parliament and its education committee were approving the budget. These were the actors with which university leaders had to constantly engage in discussions about the future of the system. The Academy of Sciences was restructured: it lost its research institutes and remained as a ‘club’ of elite professors. Nevertheless—although it did not possess its main instruments anymore, namely, research governance and funding—it continued to exert some of its power in the policy networks.

The University Rectors’ Conference has been a very central and powerful actor in higher education policy decision-making in Lithuania since 1990, lobbying the government and parliament committees to ensure that their interests were met (ibid.). It was strongly opposing the creation of a private sector in higher education and was initially successful. As shown by Leišytė (2002), attempts to introduce reforms in management and governance structures, funding and teaching methods in higher education remained rather unsuccessful. Universities also opposed the establishment of colleges to minimize competition. Consequently, in contrast to the other Baltic states (Estonia and Latvia), where the private sector had emerged at early stages of independence, the Lithuanian higher education sector initially saw a slow growth in private universities.

In 1999 and 2000, however, after many years of resistance by other actors, the first private universities gained official state recognition. Moreover—partly driven by the significant expansion of the number of students, which was caused both due to higher number of high school graduates and the entrance of older students, who needed new types of diplomas in order to requalify themselves for the new market—the LHE passed in 2000 fostered the expansion of the system by creating the non-university higher education sector. First plans to establish a non-university higher education sector and to reorganize technicums (technologically oriented professional schools established during Soviet times) and professional colleges, which were counted as post-secondary vocational education institutes back in the 1990s, into colleges were made. After long debates between the Rectors’ Conference, the Higher Education Department and the leaders of former technicums, the big structural change—the creation of a binary system of higher education—took place in 2000. The Law foresaw university (doctorate granting) and non-university (colleges or universities of applied sciences, providing undergraduate degrees) institutions of higher education. The non-university colleges were allowed to offer undergraduate level degrees. A high demand for new degree programmes, especially in the field of management and law studies, was filled in by private colleges, which started to mushroom after 2000.We can say that this Law set the conditions for deregulation and increased autonomy of higher education institutions towards the corporate state model to use Gornitzka and Maassen’s typology (2000). It also provided a framework for student fees within the auspices of the contract between the Ministry of Education and Science (MoES) and the higher education institutions according to different disciplines that covered the full costs of studies (Mockienė 2004). On October 1, 2000, there were 92,800 students in public higher education institutions of which 28,600 were self-financed (DeSHE 2001; Leišytė 2002).

Hence, we can observe that after regaining independence in 1990, Lithuanian higher education shifted between academic elite coordination and sporadic state interference. Student numbers were decreasing until 1995–1996 from 67,000 in 1990 to 54,000 in 1995 as many high school graduates preferred to go to the ‘new market’ and earn money as the prestige of higher education was dwindling. However, after the first worst transition period, the numbers of students rose sharply from 59,000 in 1996–1997 to 96,000 in 2000–2001 (Leišytė 2002). Though the OECD (2002) notes that the acceleration has not been as drastic as in other countries in the region, the demand for higher education has risen and even enhanced with the expansion and diversification of the system (OECD 2002). Due to the increase in the number of students and high demand for retraining, extramural courses flourished, which was a good source of funding for institutions, very often to the detriment of programme quality (Dobbins and Leišytė 2014).

Years 2001–2009: The Main System Expansion and EU Accession

Since the adoption of the LHE in 2000, no explicit strategic goals or priorities for higher education policy were formulated. At the same time, in 2001 the demand for higher education was rising: the gross enrolment ratio in the tertiary education in Lithuania was about 70% (UNESCO 2002/2003). This phenomenon was accompanied by concerns about the quality of higher education, the mismatch between market/society needs and university outputs (Leišytė and Kiznienė 2006). Various proposals how to address higher education’s problems were made by the Science Council of Lithuania, the Rectors’ Conference and the Ministry of Education. Policy rhetoric called for the more efficient use of scarce funding, for more accountability and better management (ibid.). According to Žalys (2004), the government programme of 2001–2004 envisaged a higher education development plan, outlining the state’s aims and objectives. However, the government did not approve the development plan drawn up by the Department of Higher Education and Science—allegedly due to a lack of political determination on the one hand and an inability to reach consensus among the main interest groups on the other. Thus, for five years higher education developed without clearly stated aims and without a clear government higher education policy except for the tacit aim of expansion.

An important development in the period of 2001–2009 included the expansion of the number of institutions as a number of private universities and colleges were created. The first private institution to be officially recognized as a university in 1999 was Vilnius St. Joseph Seminary, followed by the Lithuanian Christian College and ISM University of Management and Economics (1999), Vilnius University International Business School (2000) and Telšiai Bishop Vincentas Borisevičius Priest Seminary (2001). The real expansion of private sector did, however, take place in 2002, when the college sector saw the boom of private colleges. Traditionally, private colleges were rather small in size and narrowly oriented. They used to specialize in social sciences, management and economics offering law and business bachelor’s degrees or professional education, such as nursing. Recently, the focus of the colleges has however somewhat broadened. The private college sector served 20% of the Lithuanian college student body and was quite an important alternative in Lithuanian higher education. In the university sector, however, public universities had the majority of students, as only around 4,000 students were enrolled in private universities in 2005 (Leišytė and Kiznienė 2006).

Not only private colleges, but the whole college sector saw a boom in the early 2000s. The seven first public and private colleges were established in 2000. They offered 41 study programmes to about 3,500 students. By 2002, there were 16 public and private colleges which offered 242 study programmes to 26,000 students. A year later, the total number of colleges had grown to 27. A decrease in this number can be witnessed only after 2008/2009, when several colleges merged (Official Statistics Portal 2015).

After the first wave of significant system expansion and differentiation in early 2000, some new institutions also became part of the system. Despite the debates against private universities, one more specialized institution was created (Vilnius Academy of Business Law in 2003; renamed as Kazimieras Simonavičius University in 2012). Furthermore, two international universities became part of Lithuanian higher education system in this period. The European Humanities University (EHU) was initially founded in Minsk in 1994 in Belarus and—after having been shut down by the national authorities in 2004—was re-established in exile in Vilnius in 2005 with support from the European Union funds. The university has a strong sense of Belarusian identity and—while also admitting international academic staff and students—primarily serves as a ‘haven of academic freedom’ for Belarusian students and staff. Another example of international presence in Lithuanian higher education was the opening of a branch of the Polish University of Bialystok in Vilnius ‘Faculty of Economics-Informatics’ in 2007. It was opened following an initiative to increase the level of higher education among the Polish minority in Lithuania.

As Lithuania joined the EU in 2004, EU Structural Funds became available to the country’s higher education via the Ministry of Education and Science. As a result, a number of initiatives with implications for system differentiation and inter-organizational dynamics took place from 2006. First of all, to use the EU Structural Funds the Ministry established the Research and Higher Education Monitoring and Analysis Centre (MOSTA), which monitors the system dynamics and collects data on higher education trends in Lithuania. It has carried out various monitoring studies of higher education institutions and has provided information to the Ministry of Education and Science on demand. The most recent research evaluation of all fields in Lithuania using the methodology developed by consultants from Technopolis and carried out by MOSTA in 2014–2015 shows that the state uses this centre as a monitoring instrument which may contribute towards vertical stratification in the long run. Further, a crucial development based on the availability of the EU Structural Funds that had implications on vertical differentiation was the strengthening of the Lithuanian Research Council. Its budget was more than doubled and it has become the main provider of competitive basic research grants for academics and research groups at Lithuanian research institutions.

After 2009: Increasing Competition, Demographic Decline and Internationalization

The most recent reforms in the Lithuanian higher education were brought along by the 2009 Law on Higher Education and Research (2009). It extended the autonomy of universities even further and significantly increased competition for research funding and students due to a funding mechanism based on strong performance, as well as changed student financing system (Researchers’ Report, 2014). University status was changed into a not-for-profit institution, which entailed the need to approve new statutes of universities and to appoint rectors according to the new procedure. Besides, universities started to own their assets and became responsible for their maintenance. However, with regard to matters related to the curriculum and student admissions, academics and university management retained a strong say. Thus, academic elites still have considerable influence on the power balance of higher education governance in Lithuania, despite the indicated shifts towards the market-based paradigm. With European Union funding schemes as well as increased tuition fees, the institutions have diversified their funding base and do not depend as much on state budget allocations as they did in 2000. Given the above factors, competition in the system has significantly increased, and although we can still see the presence of the state in steering, there has also been a ‘discharging’ of state responsibility to the university management and stakeholders (Dobbins and Leišytė 2014).

In terms of institutional landscape, proposals for mergers became even more present on the policy agenda. In 2005–2006, policy rhetoric and some initiatives for an agglomeration of faculties as well as integration of research institutes into universities were observed (Žalys 2006). Imperatives of mergers of colleges and universities have been around also in 2008 (Valinčius 2008; Viliūnas 2009). After 2009, the MoES put forward financial incentives for universities from EU Structural Funds to facilitate mergers. A governmental committee was created to prepare scenarios for mergers of universities with two conflicting goals: to rescue the weak institutions which will massively loose students and, at the same time, to improve the quality of higher education. The proposal developed by the commission with the participation of the ministry basically implied a scenario of having one or two big institutions in each big city: Vilnius and Kaunas. Strong lobbies from certain university rectors were observed. However, this remained only a committee proposal, as the Minister was highly criticized for the overall reform process and did not pursue further implementation of this proposal. Especially the destiny of regional and small, specialized universities was questioned. Overall, the attempt to facilitate mergers of universities did not work as only two institutions stepped forward. In 2010, Kaunas University of Medicine and the Lithuanian Veterinary Academy merged to form the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. This happened both under pressure and with the financial assistance from the Lithuanian government (Švaikauskienė and Mikulskienė 2016).

However, mergers took place at a larger scale among research institutes, which also affected the university landscape. Mergers of research institutes into universities followed the carrot of the EU Structural Funds (e.g. the Vilnius University merger with the Biotechnology Institute). Clustering of science institutions as well as university faculties in ‘Valleys’ took place due to infrastructural financing from the EU Structural Funds in Vilnius, Kaunas and Klaipėda. After these mergers, the binary higher education system consists of 22 universities (14 public and 8 private) and 24 colleges (13 public and 11 private). Altogether, the higher education sector educated 148,389 students and employed 13,532 researchers in 2014 (Eurostat 2017a, 2017b).

In addition to these reforms, significant changes have taken place in the context of higher education institutions, including dynamics of student demand, internationalization and increasing competition for resources fuelled by demographic downturn as well as global rankings and prestige imperatives.

The student numbers in Lithuania peaked in 2008 with the prospects of a 40% demographic decline in the coming years. Partly due to this fact, internationalization has been influencing the policy agenda since the accession to the EU and the availability of the Structural Funds from 2006 onwards. A number of development plans at the MoES as well as policy discourses have focused on increasing internationalization. The acceptance of double-degree programmes, promotion of English language programmes as well as agreements between Lithuanian higher education institutions and the institutions abroad are the examples of these developments. Historically, among the private higher education institutions we have seen a strong influence of foreign institutions and funders, as well as the strong influence of Lithuanian diaspora in reviving the Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas. In terms of structures of higher education institutions, Mykolas Romeris University stands out as in the past couple of years it has strongly geared towards creation of double-degree programmes with foreign universities in France, Ukraine, Portugal, Austria, Finland, Latvia and Estonia.

The Higher Education Landscape in Contemporary Lithuania

The current Lithuanian higher education system follows to a large extent a ‘state supervision model’ (Leišytė 2002) where we have observed a policy shift in the state’s role from ‘sovereign state’ to a ‘corporate state’. Higher education institutions enjoy a high degree of organizational autonomy while facing lower levels of political and especially financial autonomy (Ritzen 2013). The European University Association (2012) has rated the Lithuanian higher education system as ‘medium low’ in financial and academic autonomy, ‘medium high’ in organizational autonomy and ‘high’ in staffing autonomy. The autonomy of universities is strongly influenced by the bureaucratic financial reporting rules as well as quality assurance arrangements, which have shifted from input- to output-based funding and from a priori to ex-post quality evaluation over the years (see Dobbins and Leišytė 2014). In terms of Gornitzka and Maassen’s (2000) typology, the state in the past decade has played a corporate role with some supermarket state features. Market-driven orientation and increased competition for resources and students were key features of the past decade (Leišytė and Kiznienė 2006; Dobbins and Leišytė 2014). In order to counteract quality deterioration, low institutional accountability during the phase of expansion and privatization in 1990s and 2000, the state “re-emerged as a monitor of quality, while at the same time trying to relinquish previous legacy of bureaucratic and procedural control” (Dobbins and Leišytė 2014).

Demographic change, fuelled by high levels of emigration, lead to increasing competition for students among a large number of higher education institutions in Lithuania (Rose and Leišytė 2017). Taking this into consideration, efforts to restructure the universities’ landscape are currently made by individual higher education institutions as well as politicians. Again, it is planned to propose higher education institutional mergers concentrating them in Vilnius and Kaunas. In 2016 Kaunas University of Technology decided to acquire shares of the private ISM University of Management and Economics. Furthermore, Kaunas University of Technology and the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences put forward the intentions to merge by 2020 with the declared goal of belonging to the top-250 universities worldwide in 2025 (KTU 2016b). Moreover, the International Business School, a private entity established by Vilnius University (IBS) became an integral part of Vilnius University in 2016. This shows that institutions are aware that competition is increasing and that institutional profiling and inter-organizational links are ever more important. While some institutions gain visibility and rankings by publications and research projects (VU is the leader here), the other ones, with no strong hard science base to compete, attempt to internationalize and find international alliances in order to strengthen their market position (e.g. Mykolas Romeris University).

Thus, today we observe the following higher education institutional types in Lithuania (see Table 11.2).

Conclusion

Over the past century, Lithuanian higher education has experienced a steady horizontal differentiation. It started with a moderate differentiation in the Soviet times and intensified after 1990 when two regional universities and new specialized universities were created, many universities opened new programmes, and Vytautas Magnus University was re-established. Horizontal differentiation was especially fostered by the Law on Higher Education and Science in 2000, as it created a binary higher education system and allowed the establishment of private universities and institutions of a non-university type. This development opened the door to a number of small private and public colleges which strongly focused on management, business and law—the subjects which were in high demand at that time. These subjects were also taught at different universities, with new management and social sciences programmes being introduced at all universities, even though they could be, for instance, specialized in sports or agriculture. This blossoming of programmes and rapid system expansion catered for the ever increasing number of students, when up to 70% of high school graduate cohorts were going to obtain higher education. Issues of quality as well as funding through tuition fees were often the topic of policy debates. The state used quality assurance instruments of programme accreditation as well as institutional evaluations to ‘tame’ the expansion of programmes and to ensure minimum quality. As the demographic reality started to change and student numbers started to drop (with the prognosis of 40% drop until 2020) the vertical differentiation started to increase even further. Some institutions in Lithuania have changed their names quite a few times, sometimes to ensure that the same rector will be in office for a longer period of time than usual (e.g. Lithuanian University of Educational Sciences, Mykolas Romeris University). At the same time, renaming institutions has served the symbolic purpose of ‘relabelling’ into a new profile, which may reflect institutions’ intentions to ‘abandon’ earlier legacies and specializations (in the case of Mykolas Romeris—former police school, and then law and social sciences orientation) and to signal that the profile of the institution has become broader.

The Lithuanian higher education system was vertically differentiated from the outset—with one main classical comprehensive university catering for the needs of the nation. This trend has been maintained after 1990. However, the stratification of the institutions has increased due to the creation of the binary system, as well as the appearance of private higher education institutions. The prestige of public traditional universities and technological universities has remained the same, with Vilnius University still being the top university in terms of research output and student numbers. The specialized public institutions are stratified into two main categories. The well-established and prestigious specialized Arts and Music Academies and the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences recruit students on a national basis and have good reputation both nationally and internationally. At the same time, regional universities as well as some private higher education institutions and public colleges serve regional needs. They enjoy moderate prestige and have certain research strengths, but their main focus is on teaching and contribution to regional economy and knowledge transfer. Recent national rankings, a variety of international rankings of study programmes and the attempt of the Ministry of Education and Science to evaluate research quality at Lithuanian universities in 2014–2015 show that the government is keen to identify ‘winners and losers’ in the system. Further, the Centre for Quality Assessment in Higher Education with its programme and institutional accreditations has indirectly sustained the system’s vertical differentiation. However, it is not that easy to establish a thoroughly stratified system in Lithuania as there are many lobby forces and a strong tradition of higher education funding on historical basis, which is not easy to uproot (Leišytė 2002). The main developments towards performance-based funding and especially the availability of science funding via Lithuanian Research Council for basic research using EU Structural Funds seem to be one of the main instruments to boost the prestige of researchers and research groups from Lithuanian universities. Teaching and research at universities have been ‘reconnected’ in stronger ways due to external research funding. In this respect, the role of the Lithuanian Research Council as well as EU funding in the stratification of the system should not be neglected.

A great number of policy actors played a crucial role in the dynamics of system expansion and contributed to horizontal differentiation. University rectors and college directors were extremely influential in lobbying the necessary amendments and opposing policy changes in order to not allow private universities to get established in Lithuanian higher education. Moreover, the binary system creation and the fact that colleges can offer only professional bachelor’s degree today demonstrate that the traditional university status is maintained. Over the years, the Ministry of Education and Science did not have much power over the higher education institutions due to the broad autonomy granted back in 1990. However, the laisser-faire period of 1990s showed that certain instruments of state steering, like the power of the purse and quality assurance, are important to try to ‘reign’ some of the system dynamics which went somewhat ‘out of hand’ in the period of 2001–2009.

The 2009 Law on Higher Education and Research was extremely important in terms of giving even more flexibility to universities in owning their assets, charging tuition fees and having the ability to act strategically and profile themselves. At the same time, it was buttressed with the power of the purse that has had an effect in terms of clustering scientific and educational base in big cities in Lithuania. Here we observe the role of the state shifting towards a corporate state as the power is given to students, their parents as well as other actors, such as the Lithuanian Research Council and university management.

However, brain drain to Western European universities as well as the demographic decline of young people in the Lithuanian higher education system call for significant policy initiatives as well as institutional actions. Students, their parents and employers are having their say in shaping the system of higher education in Lithuania. Students voting with their feet opting for certain universities or going abroad determine the destiny of quite a few higher education institutions which are at the bottom of the pecking order pyramid. Further, rankings and league tables of study programmes and universities appear to be increasingly significant for policymakers as well as institutional leaders. This is another impetus for competitive behaviour and strategic gaming for the institutions. We can see that in the past years, some rectors have been active in promoting mergers and alliances, thus contributing to vertical differentiation. In the years to come, it seems that the trend of agglomeration of faculties, programmes and further alliance building between institutions is inevitable, which will lead to even further vertical differentiation and agglomeration in the Lithuanian higher education system.

As shown in our earlier studies (Leišytė 2002; Dobbins and Leišytė 2014), many developments in higher education in the 1990s and early 2000 were strongly path dependent. Taking initiatives and introducing competitive funding were the notions that took time to be accepted in the higher education policy and practice. State steering approaches and governance arrangements took a lot of time to change. A lack of trust in governmental authorities and institutional resistance to change persisted. Initiatives to monitor the higher education system have always been perceived as a form of control by higher education institutions. At the same time, the notion of academic freedom and professional autonomy among Lithuanian academia has become stronger than ever, in this way placing the Soviet past aside.

References

Bumblauskas, A., B. Butkevičienė, S. Jegelevičius, P. Manusadžianas, V. Pšibilskis, E. Raila, and D. Vitkauskaitė. 2004. Universitetas Vilnensis 1579–2004 – Vilnius University 1579–2004. Vilnius: Vilnius University. http://www.vu.lt/site_files/InfS/Leidiniai/Vilnius_University_1579_2004.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2014.

DeSHE. 2001. Lietuvos aukstojo mokslo sistemos 2001–2005 metu pletros plano projektas [The Draft Development Plan of Lithuanian Higher Education System in the Period from 2001–2005].

Dobbins, M., and L. Leišytė. 2014. Analysing the Transformation of Higher Education Governance in Bulgaria and Lithuania. Public Management Review 16 (7): 987–1010.

Gornitzka, Å., and P. Maassen. 2000. Hybrid Steering Approaches with Respect to European Higher Education. Higher Education Policy 13 (3): 267–268.

KTU. 2016a. Kaunas University of Technology Virtual Museum. http://muziejus.ktu.lt/. Accessed 1 Sept 2016.

———. 2016b. Project of the Merger Between KTU and LSMU Was Introduced at the Ministry of Education and Science. January 22. http://ktu.edu/en/newitem/project-merger-between-ktu-and-lsmu-was-introduced-ministry-education-and-science

Leišytė, L. 2002. Higher Education Governance in Post-Soviet Lithuania, Studies in Comparative and International Education. Vol. 10. Oslo: Institute for Educational Research, University of Oslo.

Leišytė, L., and D. Kiznienė. 2006. New Public Management in Lithuania’s Higher Education. Higher Education Policy 19 (3): 377–396.

Leišytė, L., R. Želvys, and L. Zenkienė. 2015. Re-contextualization of the Bologna Process in Lithuania. European Journal of Higher Education 5 (1): 49–67.

Mašiotas, P. 1923. Švietimo reikalai Lietuvoje [Public Instruction in Lithuania]. In Visa Lietuva: Informacinė knyga 1923 metams [Lithuania: Information Book for 1923], ed. K. Pruida, 237–243. Kaunas: Centralinis Statistikos Biuras prie Finansų, Prekybos ir Pramonės Ministerijos.

Mockienė, B.V. 2004. Multipurpose Accreditation in Lithuania: Facilitating Quality Improvement, and Heading Towards a Binary System of Higher Education. In Accreditation and Evaluation in the European Higher Education Area, eds. S. Schwarz and D.F. Westerheijden, 299–322. Dordrecht: Springer.

OECD. 2002. Review of National Policies for Education: Lithuania 2002. Paris: OECD.

Official Statistics Portal. 2015. Database of Indicators: Number of Colleges. Last Modified May 15, 2015. http://osp.stat.gov.lt/en/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize1?epoch=ML

Procuta, G. 1967. The Transformation of Higher Education in Lithuania During the First Decade of Soviet Rule. Lituanus 13 (1): 71–92.

Ritzen, J. 2013. Challenges for University Policy in Lithuania. Presentation at the EIB Round Table on the Future of Higher Education, Vilnius, October 22.

Rose, A.-L., and L. Leišytė. 2017. Integrating International Academic Staff into the Local Academic Context in Lithuania and Estonia. In International Faculty in Higher Education: Comparative Perspectives on Recruitment, Integration, and Impact, eds. L. Rumbley, M. Yudkevich and P.G. Altbach. New York: Routledge.

Šakalys, J. 1985. Higher Education in Lithuania: An Historical Analysis. Lituanus: Lithuanian Quarterly Journal of Arts and Sciences 31 (4): 5–22.

Suchodolski, B. 1971. The East European University. In World Yearbook of Education 1971/2: Higher Education in a Changing World, eds. B. Holmes, D.G. Scanlon and W. R. Niblett, 120–134. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Švaikauskienė, S., and B. Mikulskienė. 2016. Autonomy Produces Unintended Consequences: Funding Higher Education Through Vouchers in Lithuania. In (Re)Discovering University Autonomy: The Global Market Paradox of Stakeholder and Educational Values in Higher Education, eds. R.V. Turcan, J.E. Reilly, and L. Bugaian, 137–147. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

UNESCO, Institute of Statistics. 2002/2003. Education: Gross Enrolment Ratio by Level of Education. http://stats.uis.unesco.org. Accessed 1 Sept 2016.

Valinčius, G. 2008. Mokslo ir studijų institucijų įrangos, žmogiškųjų išteklių koncentracijos teritorijų analizė [The Analysis of Infrastructure and Human Resources Concentration in Science and Higher Education]. Vilnius: Nacionalinės plėtros institutas.

Viliūnas, G. 2009. Kaip pertvarkyti Lietuvos universitetus [How to Reform Lithuanian Universities]. Section: Sankirtos. Bernardinai.lt. August 11. http://www.bernardinai.lt/straipsnis/-/2989

VMU. 2016. Vytautas Magnus University Now and Before. http://www.vdu.lt/en/about-vmu/vmu-now-and-before/. Accessed 1 Sept 2016.

Willerton, J.P. 1992. Patronage and Politics in the USSR. Vol. 82. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Žalys, A. 2004. Lietuvos mokslo ir studijų perspektyvos po gegužės 1-osios [Perspectives of Lithuanian Science and Higher Education After May 1]. Presentation at the DAAD Club Lietuvos mokslo ir mokymo politika, Lietuvai tampant Europos Sąjungos nare, April 17.

———. 2006. Kodėl vis dar naujai vertiname dešimties metų senumo vertinimo rezultatus? [Why Are We Evaluating the Ten Year Old Evaluation Results in a New Way?] Presentation at the Round Table Discussion “Ką pasiekėme ir ko siekiame?” [What Have We Achieved and What Are We Striving For?] at the Lithuanian Presidency, May 10.

Želvys, R. 2004. Development of Education Policy in Lithuania During the Years of Transformation. International Journal of Educational Development 24: 559–571.

Zulumskytė, A. 2014. Aukštųjų mokyklų sistema Lietuvoje 1940–1990 metais: raidos bruožai [The System of Higher Education Institutions in Lithuania in 1940–1990: Features of Development]. Tiltai 66 (1): 105–120.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Leišytė, L., Rose, AL., Schimmelpfennig, E. (2018). Lithuanian Higher Education: Between Path Dependence and Change. In: Huisman, J., Smolentseva, A., Froumin, I. (eds) 25 Years of Transformations of Higher Education Systems in Post-Soviet Countries. Palgrave Studies in Global Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52980-6_11

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52980-6_11

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-52979-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-52980-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)