Abstract

Levels of childlessness in Britain are higher than in many other European countries, with just under one in five British women currently reaching age 45 with no biological children of her own. This chapter provides new insights in two ways. First, by combining childbearing data from repeated rounds of the General Household Survey and the United Kingdom Household Panel Survey, the chapter examines how the educational gradient of childlessness has changed over birth cohorts. Second, the chapter investigates childlessness from a life course perspective among men and women born in 1970 who were followed up within the British Cohort Study. Focusing on cohort members who were childless at age 30, the relationship between fertility intentions expressed at age 30 and achieved childbearing by age 42 is examined. At age 42, the male and female respondents who remained childless were invited to give their reasons for remaining childless. Some reported that they did not have children “due to health reasons”, many more responded that they “did not ever want children”, while others said that they had “not met the right partner to have children with”. Only a few suggested that they “had been focused on their career”. We examine these responses in the context of the individuals’ partnership histories, and contribute to the debate on the question of whether the “perpetual postponement” of childbearing to later ages is acting to increase the proportion of the population who ultimately remain childless.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Interest in Britain in the causes and consequences of childlessness has grown since the 1980s in response to the increase in voluntary childlessness from very low levels in the 1960s and early 1970s (e.g., Baum and Cope 1980; Campbell 1985; Kiernan 1989). Some early authors characterised childlessness as “a mode of ultimate feminism” (McAllister and Clarke 2000), and early studies focused on women who had been married for at least 10 years but had had no children (e.g., Kiernan 1989). More recently, scholars have used a life course approach to investigate the parental background and life course factors associated with fertility intentions and outcomes (McAllister and Clarke 2000; Berrington 2004; Kneale and Joshi 2008; Simpson 2009; Berrington and Pattaro 2014). From the outset, researchers in this area have struggled with the difficulties inherent in defining and measuring voluntary and involuntary childlessness, in differentiating between those who wish to postpone childbearing and those who do not want children, and in understanding how individuals’ viewpoints change across the life course (Baum and Cope 1980; Iacovou and Travares 2011).

Relative to the rest of Europe, Britain is a particularly interesting case because it is one of the countries where overall aggregate levels of fertility are high (with a completed family size of around 1.9 births per woman), but levels of childlessness are also high (at around 20 %) (Coleman 1996; Berrington et al. 2015). This chapter provides new empirical evidence for Britain which can help us better understand this apparent contradiction. We add to the existing knowledge on this topic in a number of ways. First, we examine how the educational gradient of childlessness has changed over birth cohorts. Second, we examine childlessness trends for both men and women using a unique cohort study of individuals born in Britain in one week of April 1970. Using prospective data collected from this cohort during their adult years, we investigate how the childbearing intentions of individuals who are childless at age 30 are associated with the likelihood of remaining childless at age 42. Finally, we examine the reasons given for not (yet) having had children among those who are childless at age 42.

1.1 A Continuum of Childlessness

Traditionally, a distinction has been made between people who are involuntarily childless as a result of biological infertility, and people who are voluntarily childless. However, this distinction is not necessarily clear-cut, since, for example, individuals who are not fertile may be accepting of their childless situation (McAllister and Clarke 2000). Involuntary childlessness can arise for reasons other than health problems. The terms “childless by circumstance” or “social infertility” (which describe those who do not have a suitable partner, or who have a partner who does not want children) are used both in academic research (e.g., Carmichael and Whittaker 2007) and more generally (e.g., Black and Scull 2005; Day 2013). Indeed, while one member of a couple may be infertile or choose not to have children, for the other member this inability or unwillingness to have children may represent a circumstance which he or she has not chosen (Carmichael and Whittaker 2007). Several authors have suggested that there is a continuum of childlessness (Letherby 2002; McAllister and Clarke 2000). On one end of the continuum is a small group who report from a young adult age that they do not want to have children; the so-called “early articulators” (Houseknecht 1987). Qualitative research has suggested that such women often feel they do not have an affinity for babies or young children. There is less support for the idea that these women are making their decision to remain childless to protect a high-powered career (McAllister and Clarke 2000; Carmichael and Whittaker 2007). At the other extreme are women who are childless due to a medical condition. In between is a group of women who intended to have children, but who ended up with no children because of their circumstances (McAllister and Clarke 2000; Carmichael and Whittaker 2007; Keizer et al. 2008). There is also a category of women who never made a conscious decision about whether to have children. These women have sometimes been referred to as being “ambivalent” about childbearing. For these ambivalent women, childlessness is the consequence of having chosen to follow a particular life pattern, rather than of a decision made at an easily identified point in time.

Of particular relevance in the UK context is the association between the rise in childlessness and the increased mean age at entry into parenthood, particularly among more educated women (Berrington et al. 2015). As more couples delay childbearing, the issue of declining reproductive capacity with age becomes increasingly important. In addition, as more young adult women spend extended periods in education or pursuing career opportunities that have recently opened up to women, they may repeatedly decide to postpone childbearing, and thus drift into childlessness (Merz and Liefbroer 2012). Such individuals, who express a positive fertility intention but postpone childbearing until it is “too late”, are described by Berrington (2004) as “perpetual postponers”. Recent UK data confirm that very few individuals report that they wish to remain childless, including people who are still childless in their thirties (Ní Bhrolcháin et al. 2010; Berrington and Pattaro 2014). Some of these men and women will not be able to have the children they desire, due to age-related infecundability. It is difficult to quantify exactly what proportion of women who try to have their first baby at older ages will not succeed. Recent estimates show that rates of sterility rise after age 35 and especially after age 40, and that this increase is due not only to difficulties in conceiving, but to increased rates of fetal loss at higher ages (Leridon 2008; Eijkemans et al. 2014).

In summary, childless men and women are a very heterogeneous group. Both “active” and “passive” decision-making occurs across the life course which results in some individuals not having children (Gillespie 1999). Individuals can move along the childlessness continuum over time as their own life course develops (Baum and Cope 1980; McAllister and Clarke 2000). As Miettinen (2010: 20) noted: “For many, the decision not to have children may be a consequence of a process, where childbearing is postponed due to reasons related to relationship, personal considerations as well as financial and work-related constraints until it is too late to have children.”

There is a risk when studying childlessness that the researcher will inadvertently characterise men and women without children as somehow lacking or as deviating from the norm. Some commentators prefer to use the term “childfree” rather than “childless”, thereby emphasising that many couples who decide not to have children are making a positive choice to, for example, have more freedom and disposable income than families with children typically have (McAllister and Clarke 2000; Carmichael and Whittaker 2007). In this chapter, I use the term childlessness in its demographic sense to describe a person who has not had a biological child of his or her own, while noting that many individuals, especially men, act as social parents to children who may not be their own biological children.

Much of the previous work on childlessness has focused on women only. This is partly due to data constraints. The data published within the vital registration system generally only links births to the mother’s characteristics (ONS 2014), while in many surveys (e.g., the British General Household Survey) only female respondents are asked questions about their past fertility. It is, however, important to consider men’s experiences of childlessness as well (Jamieson et al. 2010). Choosing not to become a parent may not be equally socially acceptable for men and women (Rijken and Merz 2014). Furthermore, the factors associated with remaining childless are likely to differ by gender, as there are gender differences in, for example, the opportunity costs of childbearing. Moreover, although decisions about childbearing are often made jointly by a couple, the interaction of the partners’ desires and intentions is rarely examined. Qualitative research for the UK suggests that ambivalent women can be swayed either way by their partner’s views (McAllister and Clarke 2000), while quantitative research using longitudinal data indicates that when the intentions of the partners conflict, the probability of having further children is reduced (Berrington 2004). Among childless couples, research has generally shown that women’s intentions are stronger predictors of entry into parenthood than men’s intentions.

1.2 Aims of This Chapter

This chapter provides new insights into trends in childlessness by using an approach which compares findings for men and women and for individuals with different educational backgrounds. The following research questions are examined: How have childlessness levels changed across birth cohorts of women, and how do rates differ according to level of education? What proportion of childless individuals in their thirties say they intend to have children? Does this share differ by gender or level of education? What proportion of these “postponers” go on to have a child by age 42? How does this share vary by gender, education, and partnership history? What reasons do people give for not having had a child by age 42? How do these reasons vary by gender, level of education, and partnership history?

2 Data Sources

Three data sources are used: vital registration data, retrospective fertility histories from a series of cross-sectional surveys, and longitudinal prospective data collected within a national birth cohort study. Below, we describe the latter two data sources in more detail. The vital registration data are a long time series of data on the proportions of individuals who remain childless. The data, which are provided by the Office for National Statistics (ONS 2014), are based on births registered in England and Wales. However, these data are available for women only, and are not broken down according to any socio-economic characteristics.

2.1 Retrospective Fertility Histories from the General Household Survey and the United Kingdom Household Longitudinal Study

In order to examine how educational differentials in childlessness have changed over cohorts, we use a specially constructed dataset which combines data from repeated retrospective surveys of women carried out between 1979 and 2009 (General Household Survey Time Series dataset (Beaujouan et al. 2014)). This dataset is augmented by retrospective fertility data for recent cohorts collected within the first wave of the United Kingdom Household Panel Survey (UKHLS) (Knies 2014). Both the General Household Survey and the UKHLS collect information on respondents’ educational attainment upon leaving full-time education and their retrospective childbearing histories, and both surveys have been used to examine educational differentials in the timing and quantum of fertility in Britain (Ní Bhrolcháin and Beaujouan 2012; Berrington et al. 2015).Footnote 1 Childlessness estimates are based on responses from women aged 40–49 at the time of the survey. Women’s highest qualification upon first leaving education (i.e., at the end of continuous education) provides the best available indication of educational attainment prior to entry (or potential entry) into motherhood.Footnote 2 The analyses presented here use four categories of education: less than secondary level, secondary level, advanced level, and academic degree or equivalent. A secondary-level qualification is equivalent to a school-leaving qualification typically earned at age 16. An advanced-level qualification is typically earned at age 18, and is generally required for entry into a tertiary (university) educational institution. The interpretation of changing educational differentials in fertility over time is made more complex by the changing composition of the British population by education. The proportion of the female population who have either no qualifications or who failed to earn any secondary-level qualifications at the end of compulsory schooling (generally at age 16) decreased from 64 % of women born in 1940–1949 to just 18 % of women born in 1960–1968. Over the same cohorts, the proportion of women who earned an academic degree or another higher-level qualification increased from 9 to 20 %.

2.2 Prospective Data from 1970 British Birth Cohort

Prospective longitudinal data are needed to examine fertility intentions and their association with subsequent fertility behaviour. The UK is fortunate to have a number of birth cohort studies that have followed respondents from birth to adulthood. Data collected from people born in Britain in 1946 and 1958 have provided us with new insights into the parental background and life course factors associated with intentions to remain childless and childbearing outcomes (Kiernan 1989; Kneale and Joshi 2008; Berrington and Pattaro 2014). In this chapter, we use data for men and women born in Britain in one week of April 1970 (BCS70) who have been followed up in multiple waves of data collection through childhood and early adulthood to age 42 (Elliott and Shepherd 2006).Footnote 3 We focus on individuals who were childless at age 30 (3209 childless men and 2603 childless women). Overall, 60 % of men and 46 % of women born in 1970 were childless at age 30, but far higher proportions of academic degree-educated men and women were childless at age 30 (80 % of academic degree-educated men and 69 % of academic degree-educated women). This gap reflects the tendency among individuals with a higher level of education to postpone childbearing.

At age 30, the respondents were asked the following question: “Do you intend to have any children?” The possible answers were: “yes”, “no”, and “don’t know”. At age 42, the respondents were asked to provide details of their achieved fertility. The analyses in which we compare fertility intentions with outcomes are restricted to the respondents who were present in both the age 30 and the age 42 waves. Of those respondents who reported being childless at age 30, 73 % of the men and 80 % of the women also participated in the survey at age 42.Footnote 4 The respondents who were childless at 42 were given a showcard of possible reasons for not having had children (see Appendix). The respondents were invited to tick as many reasons as were applicable. Those who ticked more than one reason were then asked to identify the reason they consider most important. In this chapter, I focus on the most important reason given.

3 Childlessness Trends in the UK

3.1 Historical Trend in Childlessness

Figure 3.1 shows for England and Wales the percentages of women born between 1920 and 1983 who were childless at age 30 and at the end of their reproductive period. Levels of childlessness at the end of the childbearing period were very low among women born in the 1940s. Childlessness started rising among later cohorts, and then stabilised among women born in the 1960s. For example, just 9 % of women in the 1946 birth cohort, but 18 % of women born in 1968 (the most recent cohort to reach age 45), had not had a child by the end of their childbearing years. Childlessness first started to increase among the cohorts born in the 1950s, who were also the cohorts who first started postponing childbearing (Office for National Statistics 2014). These two trends are related, and later in this chapter we examine the achievement of fertility intentions among “postponers”.

Share of women who were childless at their 30th birthday and upon completion of childbearing, by year of birth of woman. England and Wales, in per cent (Source: ONS (2014))

The current levels of childlessness are not, however, historically unprecedented. As has been shown for many other European countries (Dykstra 2009) and the United States (Morgan 1991), there is evidence in the UK of a U-shaped pattern of childlessness among birth cohorts. Historically, more than one-fifth of the population of England and Wales were childless, largely as a result of non-marriage (Hajnal 1965).

Historically in Britain, there was a tradition of late marriage, and high proportions of the population never married. These trends were characteristic of the West European Marriage Pattern, as described by Hajnal (1965). In the early twentieth century, high levels of non-marriage were associated with imbalances in the sex ratio resulting from excess male emigration and male mortality during the First World War (Kiernan 1988; Dykstra 2009). Additionally, as noted by Holden (2005), non-marriage may have become economically feasible for middle- and upper-class women due to the availability of jobs in light industry, services, and businesses in urban areas.

What differentiates the patterns of contemporary cohorts from those of historical cohorts is that today the high levels of childlessness at age 30 are associated with the postponement of the start of parenthood to older ages. The share of women who were childless at age 30 rose from 18 % of those born in 1946, to 42 % of those born in 1968, and to 46 % of those born in 1983. The data suggest, however, that levels of postponement and childlessness are no longer increasing, and may have even gone into reverse, with the proportion women who are childless at 30 peaking among those born in the mid-1970s.

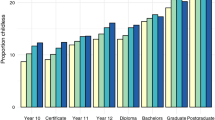

3.2 Educational Differentials in Childlessness in the UK

Figure 3.2 shows the proportions of British women who were childless at age 40 according to birth cohort and highest educational level upon first leaving full-time education. The positive educational gradient in childlessness existed in all birth cohorts starting with women born in the 1940s. The proportion childless among respondents with a tertiary education is roughly double that among respondents with no or less than secondary qualifications (i.e., the least educated). Over time, the educational gradient has increased very slightly as a result of faster increases in childlessness among women with tertiary education. Thus, among British women born in the 1960s, 22 % of university graduates, and 10 % of the least educated group remained childless.

These strong educational differences have tended to fuel discussions in the media, with commentators frequently asserting that many highly educated women in Britain are choosing to remain childless in order to “pursue a career”, or that they have postponed starting a family in response to the conflicting demands of their career, and “have left it too late” to have a child (McAllister and Clarke 2000; Hadfield et al. 2007). In the following sections, we examine the likelihood that highly educated women intend to remain childless, and how their intentions compare with those of their male counterparts.

4 Fertility Intentions and Childlessness

4.1 Fertility Intentions

Studies using a number of different data sources have consistently shown that very few British men and women intend to remain childless—at least if we take survey responses on intentions at face value (Berrington 2004; Ní Bhrolcháin et al. 2010; Berrington and Pattaro 2014). Research indicates that the proportion of individuals who intend to remain childless increases with age, as individuals adjust their intentions according to their lived experiences (Berrington 2004; Iacovou and Tavares 2011). Nevertheless, in the UK a large share of individuals who are still childless in their thirties express a strong desire to have children. This is consistent with the notion that individuals are postponing their childbearing to later ages, rather than rejecting parenthood altogether (Ní Bhrolcháin et al. 2010; Berrington and Pattaro 2014). Table 3.1 below presents the childbearing intentions at age 30 of childless men and women born in Britain in 1970, according to their highest level of qualification.

Around 3 % of men and 6 % of women said that either they or their partner were unable to have children. The percentage who reported infertility problems was much higher among respondents with lower levels of education, reflecting a selection effect whereby less educated men and women who remain childless at age 30 are a select subset of the population with lower levels of education, who typically start their childbearing at earlier ages (Kneale and Joshi 2008; Berrington et al. 2015).

Overall, the respondents’ childbearing intentions at age 30 differed little by gender: around two-thirds of both men and women who were childless expressed an intention to have at least one child, 12 % said they do not intend to have a child, while around 20 % said they are unsure. Tertiary-educated childless men and women were more likely to express a positive intention, while those with the least education were more likely to express a negative intention. The majority can therefore be classified as postponers i.e., they have a positive intention to have a child, but they remain childless. However, the fact that 20 % of the group are uncertain suggests that circumstances could easily play a role in shaping their decision.

4.2 Fertility Outcomes

Figure 3.3 examines the question of whether the respondents who were childless at age 30 had entered parenthood by the time they were interviewed in 2012, when they were age 42. Once again, there is remarkable consistency in the findings for childless men and women. Fertility intentions at age 30 were a good predictor of fertility outcomes: around 30 % of those who said they intend to have a child remained childless at age 42, compared to around one-half of those who said they are uncertain in their intentions, and around three-quarters of those who said they do not intend to have a child. Half of both male and female postponers—i.e., those who said they intend to have children—went on to have two or more children. Of those who did not intend to have any children, 11 % of men and 18 % of women went on to have at least one child. Thus, the fertility intentions of the respondents were both under- and overachieved, but the levels of underachievement were higher. Men and women with uncertain intentions appear to have behaved in a similar fashion: compared to respondents with positive intentions, they were more likely to have remained childless or to have had just one child, and they were less likely to have had a second child. In further analyses (not shown) highly educated men and women are found to be more likely than less educated individuals to achieve their positive intentions for childbearing at older ages. This is consistent with earlier findings (Berrington 2004; Berrington and Pattaro 2014), and is likely to be related to the selection effect whereby individuals from lower educational groups who remain childless at age 30 are more likely to have other socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., health problems) associated with a lower likelihood of becoming a parent.

Distribution of achieved family size at age 42, according to intentions at age 30. 1970 British Cohort Study members who were childless at age 30, in per cent. Sample size for men is: 1359 Yes, 441 Don’t know, 280 No. Sample size for women is: 1260 Yes, 345 Don’t know, 246 No (Source: Author’s analysis of BCS70)

4.3 Partnership Experience and the Likelihood of Achieving Intentions

An important pathway through which positive fertility intentions remain unrealised is partnership experience (McAllister and Clarke 2000; Berrington 2004; Carmichael and Whittaker 2007; Berrington and Pattaro 2014). To gain a better understanding of this dynamic, let us look at BCS70 cohort members who were childless and had never lived in a co-residential union at age 30, but who had a positive intention to have a child. Table 3.2 shows the percentage of this group who remained childless by their partnership status at age 42. Of course, we cannot tell from these data the extent to which partnership status had a causal effect on childlessness, since both partnership formation and childbearing are likely to be influenced by other factors, such as the respondent’s health status, work ambitions, and attitudes regarding family formation. Nevertheless, the table clearly shows that partnership experience plays a key role in childlessness over the life course. The vast majority (nine out of ten men and eight out of ten women) of those who were never married and did not have a co-residential partner at age 42 remained childless. By comparison, about half of those who were in a cohabiting relationship at age 42 remained childless. The group most likely to have achieved their fertility intentions were those who married after age 30 and remained married at 42; only one-fifth of this group remained childless. In comparison, levels of childlessness were higher among those who married after age 30 but subsequently separated.

5 Reasons for Remaining Childless

Of the BCS70 respondents at age 42, one-quarter of the men and just under one-fifth of the women had never had a biological child of their own. Consistent with our earlier findings for women based on the General Household Survey/Understanding Society Survey (Sect. 3.3.2), we observe a strong positive educational gradient in the proportion childless among women: one-quarter of female university graduates born in 1970 remained childless, compared to 15 % of women with less than secondary qualifications.Footnote 5 However, among the male cohort members, the differences by educational level in the proportion childless were much smaller (27 % of male university graduates were childless at 42, compared to 23 % of men with less than secondary-level qualifications).

5.1 Work and Careers Not Reported as the Main Reason

Table 3.3 shows the reasons given by childless respondents at age 42 for why they had not (yet) had children. Recall that respondents were asked to tick the possible reasons, which are shown in the Appendix. Three main reasons dominate the responses. The most common reason was that the respondent had not wanted children (cited by 28 % of men and 31 % of women). The second most common reason was that the respondent had never met the right person (cited by 23 % of men and 19 % of women). A similar share of women cited health reasons: i.e., that they or their partner were infertile, or had some other health problem. Men were less likely to cite their own infertility as a reason for childlessness.

Other reasons were less prevalent. A small share of respondents (3 % of men and 4 % of women) said their partner did not want children, which reminds us of the importance of the couple in childbearing behaviour. A significant minority, 18 % of male and 12 % of female childless respondents, did not tick any reason.

Some respondents agreed with the statement that they had wanted children, but had not got around to it, which suggests ambivalence about childbearing. Just 3 % of men and 2 % of women cited being focused on their career as their main reason for remaining childless. In further analyses (not shown), we compare the reasons given according to the highest level of education. While childless university graduates were slightly more likely than others to have responded that they were focused on their career, the shares were still only 4 % of men and 3 % of women. These findings are in stark contrast to the prevailing tone of media discussions, which often portray childless women as being too focused on their career.

In fact, we see two main differences in the distribution of reasons for childlessness based on the highest level of education. First, health reasons were cited by a higher proportion of the least educated women. Second, both male and female university graduates had a greater tendency than respondents with less education to report that they had never met the right person: 30 % of male and 34 % of female university graduates gave this response, compared with 19 % of men and 28 % of women with less than a secondary education.

5.2 The Importance of Having a Partner

Table 3.4 presents the reasons for remaining childless by legal marital status at age 42. We show the pattern for women only, since the findings for men are very similar. Those women who had been married but who had remained childless were more likely than women who had never married to say either that they had not wanted to have children, or that there were health reasons that had prevented them from having children. By contrast, among those who had never married, almost one-third said they had never met the right person, and another 30 % said they had not wanted to have children. Interestingly, the proportion of respondents who reported that their partner had not wanted children was slightly higher among those who were divorced or separated; at around 6 %. The divorced, separated, and widowed group were also quite likely to say they had not met the right person.

6 Discussion

This chapter has provided new insights into childlessness in Britain by showing how the overall trend masks considerable educational differences in the likelihood of not having children. Unlike in some other European countries, such as the Netherlands (van Agtmaal-Wobma and van Huis 2008) and Norway (Andersson et al. 2009), educational differentials in childlessness are not narrowing over time, but remain large, and are even increasing slightly. Today, tertiary-educated women are roughly twice as likely as women with low levels of education to remain childless. The co-existence in Britain of relatively large completed family sizes (of around 1.9 children per woman) with high levels of childlessness results from different childbearing patterns within different sub-groups of the population (Berrington et al. 2015). High levels of childlessness among tertiary-educated women are being offset by relatively high rates of progression to third and fourth births, especially among mothers with the lowest levels of education (Berrington et al. 2015). The cohort fertility rates for women born in the 1980s suggest that childlessness, both at age 30 and upon completion of childbearing, may no longer be increasing. Thus, we may not see in Britain the very high levels of childlessness currently observed in countries like Austria and Italy.

Levels of childlessness, at least at age 42, are higher among British men than among British women, although it is of course possible for men to enter fatherhood at older ages. Nevertheless, a significant minority of men will remain childless. Educational differentials in childlessness are much smaller among men than among women. The proportion of men without children is high both among more educated and less educated men, though we might speculate that the pathways through which this occurs differ according to socio-economic status. Consistent with Demey et al. (2014), we see a significant minority of socio-economically disadvantaged men who are not given the opportunity for family formation. Quantitative evidence from the 1970 and previous 1958 British cohorts (Berrington and Pattaro 2014) and qualitative evidence from Jamieson et al. (2010) suggest that for some men (particularly socio-economically disadvantaged men), finding a partner can be very difficult, which leads indirectly to unfulfilled childbearing intentions. While some women with low levels of education are unable to fulfil their childbearing intentions between ages 30 and 42, the share among women is much smaller than it is among men.

Our findings regarding fertility intentions and outcomes for the 1970 British birth cohort suggest that relatively few men and women are rejecting parenthood. In terms of the “continuum of childlessness”, this so-called “certain group” (or “early articulators”) who declare that they do not intend to have children are a minority (around about one in eight of those who are childless at age 30).Footnote 6 The majority of both men and women are “postponers”, as at age 30 just under two-thirds of childless men and women express a positive intention to have a child. There is a substantial group of childless men and women who report having uncertain fertility intentions. Some of these respondents would probably fall into the “ambivalent group”, as described by McAllister and Clarke (2000), who have not explicitly considered whether they intend to have children. Other uncertain respondents may have considered their ideal family size, but remain uncertain about having a child because they are unsure of their situation. For example, they may not know whether they will have a suitable partner who also wants children, or whether childcare will be available. The significance of uncertainty in fertility intentions has not received the attention it should (although see Berrington 2004; Ní Bhrolcháin et al. 2010; Ní Bhrolcháin and Beaujouan 2011). Evidence from the 1970 cohort suggests that those who are uncertain have an intermediate chance of having a first birth: i.e., in between those who have a negative intention and those who have a positive intention. Thus, if those who were uncertain had been included in the group with positive fertility intentions, there would have been a lower level of agreement between intentions and outcomes. Moreover, uncertain intentions might reflect the fact that intentions for childbearing can be affected by period circumstances, such as partnership status and the availability of childcare, some of which could be affected by social policy changes.

Consistent with findings from earlier UK and US cohorts, respondents both under- and overachieve their intended fertility (Morgan and Rackin 2010; Berrington and Pattaro 2014), but childless postponers are more likely to underachieve: overall, 30 % of those who were childless at age 30 and who said they intend to have a child were still childless at age 42. Interestingly, this share is almost identical for male and female postponers. It is of course possible that the respondents’ intentions were modified between ages 30 and 42 in response to circumstances such as partnership experiences and work situations. Consistent with Berrington (2004), we find that the percentage of postponers who achieved their intentions was higher among men and women with higher levels of education and those who married (and stay married). Over one-third of postponing men with no or secondary-level qualifications remained childless at age 42.

Morgan (1991) cautioned against viewing childlessness as a modern phenomenon, and suggested that the reasons why people are childless today may not be very different from those of previous generations. In this British cohort, childless respondents gave a variety of reasons for not having had a child at age 42: around three in ten said they “had not wanted children”, and two in ten said they had “never met the right person”. Health issues were also frequently cited, especially by women, who were more likely than men to have reported their own infertility problems. It would be useful to know the extent to which these health problems were associated with the postponement of fertility and age-related declines in fecundability. If health played an important role, the association between increased postponement and increased childlessness among cohorts born from the 1950s onwards may be partially causal.

Comparatively few men and women reported that they had not had children because they had “not got round to it” or were “focused on career”. The finding that career demands do not play a large role in the decision to remain childless is consistent with previous research for the UK, Australia, and Finland (McAllister and Clarke 2000; Carmichael and Whittaker 2007; Miettinen 2010). The reported reasons for childlessness are similar across genders and levels of education, but differ more by partnership history. Finding and staying together with an appropriate partner appears to be a key element in childbearing decisions.

This study has a number of limitations. The type of evidence collected in quantitative surveys is limited, and individuals’ statements about the number of children they want are likely to be subject to social desirability effects and post-hoc rationalisations. The chapter presents intentions as measured at age 30, and outcomes at age 42. It would be interesting to know how individuals’ intentions change between ages 30 and 42 in response to life course events. Second, while this study is novel in that childlessness data are available for both men and women, the data do not provide information about couples. As childbearing is generally a couple-level activity, one would ideally want to investigate the preferences and constraints of both partners. Finally, many of the reasons offered to respondents in the BCS70 questionnaire for not having had children are negative, such as being in poor health or not having found the right partner. Ideally, the reasons offered should also include positive pull factors of being childfree, such as having more freedom and disposable income (Gillespie 2003). Around 30 % of childless women ticked the “not wanted to have children” box but this still leaves open the question of why they did not want to have children.

In summary, childlessness increased first among the cohorts born in the 1950s, who were also the first cohorts to start postponing childbearing. Postponement and childlessness may be causally related, e.g. through reduced fecundity with age, but both are also manifestations of underlying changes in women’s lives, such as opportunities for women to develop a career, the availability of reliable contraception, and increased partnership postponement and instability (Murphy 1993; Hobcraft and Kiernan 1995; Thomson et al. 2012).

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

We recognise that the level of educational attainment among some women is a result of their childbearing patterns: i.e., some of the youngest mothers may have had to leave full-time education as a result of becoming pregnant.

- 3.

Since this is a birth cohort study of those born in Britain in 1970, the sample is primarily white British. No attempt is therefore made to examine ethnic differences in childlessness. Further details of the on-going study can be found here: http://www.cls.ioe.ac.uk/

- 4.

Response rates were slightly higher among degree-educated men and women (80 % and 85 %, respectively). Thus, more advantaged socio-economic groups may be over-represented in the reasons for childlessness.

- 5.

For this analysis only, educational attainment is measured at age 42 so as to maximise sample size.

- 6.

We note that there may be a social desirability effect whereby British respondents may be unwilling to express a desire to remain childless, as British society and media tend to have a pro-natalist bias (Hadfield et al. 2007).

Literature

Andersson, G., Knudsen, L. B., Neyer, G., Teschner, K., Rønsen, M., Lappegård, T., Neyer, G., Skrede, K., Teschner, K., & Vikat, A. (2009). Cohort fertility patterns in the Nordic countries. Demographic Research, 20, 313.

Baum, F., & Cope, D. R. (1980). Some characteristics of intentionally childless wives in Britain. Journal of Biosocial Science, 12, 287–300.

Beaujouan, E., Brown, J., & Ní Bhrolcháin, M. (2011). Reweighting the general household survey, 1979–2007. Population Trends, 145, 119–145.

Beaujouan, E., Berrington, A., Lyon-Amos, M., & Ní Bhrolcháin, M. (2014). User guide to the Centre for Population Change GHS database 1979–2009 (CPC working paper 47). Southampton: ESRC Centre for Population Change.

Berrington, A. M. (2004). Perpetual postponers? Women’s, men’s and couple’s fertility intentions and subsequent fertility behaviour. Population Trends, 117, 9–19.

Berrington, A., & Pattaro, S. (2014). Educational differences in fertility desires, intentions and behaviour: A life course perspective. Advances in Life Course Research, 21, 10–27.

Berrington, A., Stone, J., & Beaujouan, E. (2015). Educational differentials in timing and quantum of fertility: Evidence from 1940–1969 cohorts. Demographic Research, 33, 26.

Bhrolcháin, N., & Beaujouan, E. (2011). Uncertainty in fertility intentions in Britain, 1979–2007. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 9, 99–129.

Black, R., & Scull, L. (2005). Beyond childlessness: For every woman who ever wanted to have a child – And didn’t. London: Rodale International Ltd.

Campbell, E. (1985). The childless marriage: An exploratory study of couples who do not want children. London: Tavistock Publications.

Carmichael, G. A., & Whittaker, A. (2007). Choice and circumstance: Qualitative insights into contemporary childlessness in Australia. European Journal of Population, 23, 111–143.

Coleman, D. (1996). Europe’s population in the 1990s. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Day, J. (2013). Rocking the life unexpected: 12 weeks to your Plan B for a meaningful and fulfilling life without children. Seattle: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Demey, D., Berrington, A., Evandrou, M., & Falkingham, J. (2014). Living alone and psychological well-being in mid-life: Does partnership history matter? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 68, 403–410.

Dykstra, P. A. (2009). Childless old age. In P. Uhlenberg (Ed.), International handbook of population aging (pp. 671–690). Dordercht: Springer.

Eijkemans, M. J., van Poppel, F., Habbema, D. F., Smith, K. R., Leridon, H., & te Velde, E. R. (2014). Too old to have children? Lessons from natural fertility populations. Human Reproduction, 29, 1304–1312.

Elliott, J., & Shepherd, P. (2006). Cohort profile: 1970 British birth cohort (BCS70). International Journal of Epidemiology, 35, 836–843.

Gillespie, R. (1999). Voluntary childlessness in the United Kingdom. Reproductive Health Matters, 7, 43–53.

Gillespie, R. (2003). Childfree and feminine: Understanding the gender identity of voluntarily childless women. Gender & Society, 17(1), 122–136.

Hadfield, L., Rudoe, N., & Sanderson‐Mann, J. (2007). Motherhood, choice and the British media: A time to reflect. Gender and Education, 19, 255–263.

Hajnal, J. (1965). European marriage patterns in perspective. In D. V. Glass & D. E. C. Eversley (Eds.), Population in history. London: Arnold.

Hobcraft, J. N., & Kiernan, K. E. (1995, September). Becoming a parent in Europe. Plenary paper for European population conference (pp. 27–65). In EAPS/IUSSP Proceedings of European population conference Milan.

Holden, K. (2005). Imaginary widows: Spinsters, marriage, and the “lost generation” in Britain after the Great War. Journal of Family History, 30, 388–409.

Houseknecht, S. K. (1987). Voluntary childlessness. In B. Marvin & S. K. Steinmetz (Eds.), Handbook of marriage and the family (pp. 369–395). New York: Plenum Press.

Iacovou, M., & Tavares, L. P. C. (2011). Yearning, learning, and conceding: Reasons men and women change their childbearing intentions. Population and Development Review, 37, 89–123.

Jamieson, L., Milburn, K. B., Simpson, R., & Wasoff, F. (2010). Fertility and social change: The neglected contribution of men’s approaches to becoming partners and parents. The Sociological Review, 58, 463–485.

Keizer, R., Dykstra, P. A., & Jansen, M. D. (2008). Pathways into childlessness: Evidence of gendered life course dynamics. Journal of Biosocial Science, 40(06), 863–878.

Kiernan, K. E. (1988). Who remains celibate? Journal of Biosocial Science, 20, 253–264.

Kiernan, K. E. (1989). Who remains childless? Journal of Biosocial Science, 21, 387–398.

Kneale, D., & Joshi, H. (2008). Postponement and childlessness: Evidence from two British cohorts. Demographic Research, 19. http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol19/58/. Accessed 28 July 2015.

Knies, G. (2014). The UK household longitudinal study waves 1–4. User manual. https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/documentation/mainstage. Accessed 28 July 2015.

Leridon, H. (2008). A new estimate of permanent sterility by age: Sterility defined as the inability to conceive. Population Studies, 62, 15–24.

Letherby, G. (2002). Childless and bereft?: Stereotypes and realities in relation to ‘voluntary’ and ‘involuntary’ childlessness and womanhood. Sociological Inquiry, 72, 7–20.

McAllister, F., & Clarke, L. (2000). Voluntary childlessness: Trends and implications. In G. R. Bentley & C. G. Mascie-Taylor (Eds.), Infertility in the modern world. Present and future prospects (pp. 189–237). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Merz, E. M., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2012). The attitude toward voluntary childlessness in Europe: Cultural and institutional explanations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 587–600.

Miettinen, A. (2010). Voluntary or involuntary childlessness? Socio-demographic factors and childlessness intentions among childless Finnish men and women aged 25–44. Finnish Yearbook of Population Research, 45, 5–24.

Morgan, S. P. (1991). Late nineteenth-and early twentieth-century childlessness. American Journal of Sociology, 97, 779–807.

Morgan, S. P., & Rackin, H. (2010). The correspondence between fertility intentions and behavior in the United States. Population and Development Review, 36, 91–118.

Murphy, M. (1993). The contraceptive pill and women’s employment as factors in fertility change in Britain 1963–1980: A challenge to the conventional view. Population Studies, 47, 221–243.

Ní Bhrolcháin, M., & Beaujouan, E. (2012). Fertility postponement is largely due to rising educational enrolment. Population Studies, 66, 311–327.

Ní Bhrolcháin, M., Beaujouan, E., & Berrington, A. M. (2010). Stability and change in fertility intentions in Britain 1991–2007. Population Trends, 141, 13–35.

ONS (Office for National Statistics). (2014). Childbearing for women born in different years, England and Wales, 2013. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/fertility-analysis/childbearing-for-women-born-in-different-years/2013/stb-cohort-fertility-2013.html#tab-Childlessness. Accessed 28 July 2015.

Rijken, A. J., & Merz, E. M. (2014). Double standards: Differences in norms on voluntary childlessness for men and women. European Sociological Review, 30, 470–482.

Simpson, R. (2009). Delayed childbearing and childlessness in Britain. In J. Stillwell, D. Kneale, & E. Coast (Eds.), Fertility, living arrangements, care and mobility: Understanding population trends and processes (Vol. 1, pp. 23–40). Dordrecht: Springer.

Thomson, E., Winkler-Dworak, M., Spielauer, M., & Prskawetz, A. (2012). Union instability as an engine of fertility? A microsimulation model for France. Demography, 49, 175–195.

van Agtmaal-Wobma, E., & van Huis, M. (2008). De relatie tussen vruchtbaarheid en opleidingsniveau van de vrouw [The relationship between fertility and educational level of women]. Bevolkingtrends, 56, 32–41.

Acknowledgements

This work is part-funded by the ESRC Centre for Population Change (CPC). CPC is a joint initiative of the Universities of Southampton, St Andrews, Edinburgh, Stirling, Strathclyde; in partnership with the Office for National Statistics, and National Records for Scotland. The Centre is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) grant number RES-ES/K007394/1. The General Household Survey is conducted by the Office for National Statistics. The United Kingdom Household Longitudinal Study is conducted by the Institute for Social and Economic Research at the University of Essex. The CPC GHS time series data-file was constructed in collaboration with Máire Ní Bhrolcháin, Éva Beaujouan and Mark Lyons Amos. The 1970 British Birth Cohort (BCS70) is conducted by the Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute for Education, London. Access to all data is provided by the UK Data Archive. Neither the original data creators, depositors, or funders bear responsibility for the further analysis or interpretation of the data presented in this study. Thanks are due to Juliet Stone and Éva Beaujouan who commented on early versions of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix

Appendix

Most Important Reason for Remaining Childless Showcard.

1970 British Birth Cohort Study, Age 42 Questionnaire.

-

1.

Infertility problems

-

2.

Partner sterilized, had vasectomy/hysterectomy

-

3.

Other health reasons

-

4.

I have not wanted to have children

-

5.

I have wanted to have children but not got round to it

-

6.

I have been focused on my career

-

7.

I have never met the right person to have children with

-

8.

My partner has not wanted to have children

-

9.

My partner already has children and has not wanted more

-

10.

I have not wanted to compromise my relationship with my partner

-

11.

My financial situation would have made it difficult

-

12.

My housing situation would have made it difficult

-

13.

No particular reason

-

14.

Other reason – please write in:__________________________

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2017 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Berrington, A. (2017). Childlessness in the UK. In: Kreyenfeld, M., Konietzka, D. (eds) Childlessness in Europe: Contexts, Causes, and Consequences. Demographic Research Monographs. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44667-7_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-44667-7_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-44665-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-44667-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)