Abstract

Contingent convertible bonds (CoCos) are new hybrid capital instruments that have a loss absorbing capacity which is enforced either automatically via the breaching of a particular CET1 level or via a regulatory trigger. The price performance of outstanding CoCos, after a new CoCo issue is announced by the same issuer, is investigated in this paper via two methods. The first method compares the returns of the outstanding CoCos after an announcement of a new issue with some overall CoCo indices. This method does not take into account idiosyncratic movements and basically compares with the general trend. A second model-based method compares the actual market performance of the outstanding CoCos with a theoretical model. The main conclusion of the investigation of 24 cases of new CoCo bond issues is a moderated negative effect on the outstanding CoCos.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Contingent convertible bonds or CoCo bonds are new hybrid capital instruments that have a loss absorbing capacity which is enforced either automatically via the breaching of a particular CET1 level or via a regulatory trigger. CoCos either convert into equity or suffer a write-down of the face value upon the appearance of such a trigger event.

The financial crisis of 2007–2008 triggered an avalanche of financial worries for financial institutions around the globe. After the collapse of Lehman Brothers, governments intervened and bailed out banks using tax-payers money. Preventing such bail-outs in the future, and designing a more stable banking sector in general, requires both higher capital levels and regulatory capital of a higher quality. The implementation under the new regulatory frameworks like Basel III and Capital Requirement Directive IV (CRD IV) tries to achieve this in various ways, i.e. with the use of CoCo bonds (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision [1], European Commision [2]). CoCo bonds are allowed as new capital instruments by the Basel III guidelines. The Swiss regulators have forced their systemic important banks to issue large amounts of these instruments. Further, the European CRD IV which entered into force on 17 July 2013 enforces all new additional Tier 1 instruments to have CoCo features.

The specific design of a CoCo bond enhances the capital of a bank when it is in trouble in an automatic way. Hence, a loss-absorbing cushion is created with the aim to avoid or at least to reduce potential interventions using tax-payers’ money.

The first CoCos have been issued in the aftermath of the credit crisis. In December 2009 Lloyds exchanged some of their old hybrid instruments into this new type of bonds in order to strengthen their capital position after the bank had been hit very hard due to the financial crisis of 2008. Since then a lot of other banks have been issuing CoCos and one is expecting that many will follow in the next years. The market of CoCos is currently above USD 100 bn and is expanding very rapidly.Footnote 1

When an issuer has already some CoCos outstanding and is announcing the issuance of a new CoCo bond, there are at least two opposite forces at work. On one hand, a new issue means that the capital of the issuing institute is strengthened (at the additional Tier 1 or Tier 2 level). Due to the new issue, the losses in case of a future trigger event will be shared over a larger bucket and hence recovery rates are expected to be higher. On the other hand, there are the market dynamics and investors who often prefer to invest rather in the new CoCo than in the older ones. This can be just due to the fact that one prefers new things above old stuff, but also because one believes there is a basis spread to be earned on a new issuance. Some believe a new issuance is brought to the market with a certain discount, to attract investors and to make the whole capital raising exercise a success. Investors then will move out of the old bonds and ask for allocation in the new issue.

In this paper, we estimate the price impact on the outstanding CoCos via two methods. The first method compares the returns of the outstanding CoCo bonds after an announcement of a new issue with some overall CoCo indices. More precisely, we compare the performance with CS Contingent Convertible Euro Total Return index and the BofA Merrill Lynch Contingent Capital index. Here we basically compare the performance of the outstanding CoCos with the general market performance. However such a comparison does not take into account idiosyncratic movements; it basically compares with the general market trend. The issuing company is nevertheless exposed to market dynamics. Its stock price, its credit worthiness etc. can exhibit different timely evolutions compared with the respective quantities of their competitors. This can be especially the case around capital raising announcements since then financial details of the company are published and discussed at, for example road-shows around the new issuance. Therefore, we also deploy a second methodology taking into account idiosyncratic movements. Using an equity derivatives model, we compare the actual market performance of the outstanding CoCo bonds, with a theoretical model performance taking into account idiosyncratic effects, like movements in the underlying stock, credit default spreads or volatilities. The model is derivatives based and is taking as such forward-looking expectations into account.

In total, we investigate 24 cases of new CoCo bond issues. The main conclusion of the investigation is that there is a moderated negative effect on outstanding CoCo bonds. This is confirmed by both methodologies and the impact is an underperformance of about 25–50 bps on average in between the announcement date and the issue date. An extra negative impact of 40 bps was observed in the 10 trading days after the issue.

The analysis in this paper is constrained to CoCo bonds only, but a similar study could be done for other types of bonds as well. A comparative study for corporate bonds was, e.g. done in Akigbe et al. [3], where the authors investigate the impact of 574 outstanding debt issues. The investigation was divided by different reasons of a new debt issue. A significant negative impact on the price of the outstanding debt and equity was observed in case the public debt securities were issued to finance unexpected cash flow shortfalls. No significant reaction was observed when the new debt issues were motivated by unexpected increase in capital expenditures, unexpected increase in leverage or expected refinancing of outstanding debt.

This paper is organized as follows. We first provide in the next section the details of the equity derivatives model. In Sect. 3, we provide details on the data set used and in particular overview the new issuances of a whole battery of issuers that are part of our study. Next, we report on the exact methodology and results of our comparison with other CoCo indices. The final part of that section reports and discusses the results of the Equity Derivatives model. The final section concludes.

2 The Equity Derivatives Model

CoCos are hybrid instruments, with characteristics of both debt and equity. This gives rise to different approaches for pricing CoCos. Without considering the heuristic models, two main schools of thoughts exist, namely the structural models and market-implied models. Structural models are based on the theory of Merton and can be found in Pennacchi [4] and Pennacchi et al. [5]. We will apply a market-implied model where the derivation is based on market data such as share prices, credit default spreads and volatilities. The models were introduced in a Black–Scholes framework in De Spiegeleer and Schoutens [6] and De Spiegeleer et al. [7]. Pricing CoCos under smile conform models can be found in Corcuera et al. [8]. Based on the Heston model, the impact of skew is discussed in De Spiegeleer et al. [9]. In De Spiegeleer et al. [10] the implied CET1 volatility is derived from the market price of a CoCo bond. Further extensions and variations can be found in De Spiegeleer and Schoutens [11, 12], Corcuera et al. [13], De Spiegeleer and Schoutens [14], Cheridito and Zhikai [15], Madan and Schoutens [16].

The actual valuation of a CoCo incorporates the modelling of both the trigger probability and the expected loss for the investor. Notice that the trigger is defined by a particular CET1 level or decided upon a regulator’s decision. Since these trigger mechanisms are hard to model or even quantify, we project the trigger into the stock price framework as considered in the equity derivatives model of De Spiegeleer and Schoutens [6]. This means that the CoCo will be triggered under the model once the share price drops below a specified barrier level, denoted by \(S^\star \). We infer from existing CoCo market data the share price at the moment the CoCo bond gets triggered and we will call this the (implied) trigger level. As a result the valuation of a CoCo bond is transformed into a barrier-pricing exercise in an equity setting.

Under such a framework the CoCo bond can be broken down to several different derivative instruments. In first place, the CoCo behaves like a standard (non-defaultable) corporate bond where the holder will receive coupons \(c_i\) on regular time points \(t_i\) together with the principal N at maturity T. However, in case the share price drops below the trigger level \(S^\star \), the investor will lose his initial investment and all future coupons. This will be modelled by short positions in binary down-and-in (BIDINO) options with maturities \(t_i\) for each coupon \(c_i\) and a BIDINO with maturity T to model the cancelling of the initial value. After the trigger event has occurred, the investor of a conversion CoCo will receive \(C_r\) shares. We can model this with \(C_r\) down-and-in asset-(at hit)-or-nothing options on the stock. For a write-down CoCo, the investor does not receive any shares and we can just set \(C_r\) equal to zero in this case. Therefore, the price of a CoCo can be calculated with the following formula:

Under the Black–Scholes model, we can find an explicit formula for the price of the CoCo at time t:

with

where \(\varPhi \) is the cdf of a standard normal distribution, r is the risk free rate, q the dividend yield and \(\sigma \) the volatility.

Applying this equity derivatives pricing model, a CoCo price can be found for a trigger level \(S^\star \). However, the other way around is often more interesting. Knowing the market CoCo price, we can filter out an implied trigger \(\widehat{S^\star }\) in such a way that market and model price match. Since CoCos of one financial institution with the same contractual trigger should trigger at the same time, their implied trigger levels should theoretically also be the same. Hence the implied barriers give us a way to compare different CoCos in order to detect over- or undervaluation, irrespectively of different currencies and maturities.

Our goal is to compare the actual market performance of the outstanding CoCo bonds with the theoretical model performance. This theoretical price takes idiosyncratic effects into account. Any changes in the actual market performance compared to the theoretical model performance will be described to the effect of the announcement of a new CoCo issuance. The research can also be translated in terms of implied trigger levels. In case the new CoCo does not influence the outstanding CoCo, the implied barrier of the outstanding CoCo should remain constant. Whereas if its implied barrier derived from the market will change, this change will be caused by the new CoCo issuance.

3 Measuring the Price Performance of the Outstanding CoCos

3.1 New Issuances

The impact of a new CoCo issuance is investigated on the outstanding CoCos of the same issuing company. The issuers in our study contain UBS, Barclays, Crédit Agricole, Sociéty Général, Deutsche Bank, UniCredit, Credit Suisse, Santander, Rabobank, Danske and BBVA. The effect on the outstanding CoCos is investigated in the period between announcement and issuance of the new CoCo, which are summarised in Table 1. Notice that UBS, Barclays and Crédit Agricole all have issued different CoCos on the same day. Since it is not possible to distinguish their influence from each other, these new CoCos are assumed to have one general impact on all the outstanding CoCos of the same issuing company.

3.2 CoCo Index Comparison

The first analysis is based on indices as a benchmark to observe a certain impact. It basically compares the returns of the outstanding CoCo bonds after an announcement of a new issue with some overall CoCo indices. More precisely, we compare the performance with the CS Contingent Convertible Euro Total Return index and the BofA Merrill Lynch Contingent Capital Index (whenever the data is available). The methods are explained for one particular new CoCo issuance, namely the USF22797YK86 CoCo of Crédit Agricole. In the end, the overall results and conclusions are shown.

3.2.1 Method

In a first step, we analyse the impact of each new CoCo separately on all the outstanding CoCos of the same issuer. The simple returns are derived for the outstanding CoCos during the period between the announcement date and the issue date of the new CoCo. In a second step, we accumulate these simple returns and obtain the returns between announcement and issue date. As an example, the first steps are shown for two outstanding CoCos of Crédit Agricole in Fig. 1.

On each day, we calculate the (equally weighted) average of the cumulative simple returns of all outstanding CoCos. In a last step, we take the difference between these averages and the cumulative returns of the CoCo index on each day between the announcement date and issue date of the new CoCo.

3.2.2 Results

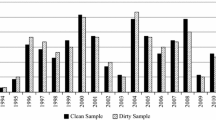

In Table 2, the difference in cumulative returns over the observation period, meaning the period between announcement and issuance, is shown. For some observation periods, the Merrill Lynch index did not yet exist. When the CoCo does show a significant change compared to the global index, we can assume that this change is due to the new CoCo issuance. The averaged difference over all new CoCos analysed is shown in Fig. 2. These averaged differences in cumulative returns are shown for one day until five days after the announcement of the new CoCo and also over the full period as was given in Table 2. As a conclusion, we see that on average the outstanding CoCos get a negative impact of around 25 bps on their return between announcement and issuance due to a new CoCo.

Multiple CoCo indices can be used for this analysis but CoCo indices are relatively new on the market. As such we are obliged to restrict our analysis to indices already available during the period of each analysis. Remark also that we need to handle these indices with care, in the sense that the indices are applied to give a global market view on the CoCos. A point of criticism to this approach can be that the indices are not that representative for the true market. There is also high concentration on some issuers in the indices, e.g. for the ML index the top 5 issuers almost make 50 % of the index (as of December 2014).

Furthermore, this comparison with the general market performance does not take into account idiosyncratic movements but compares with the general market trend. The issuing company is nevertheless exposed to individual dynamics. Its stock price, its credit worthiness, etc. can change differently from their competitors. This can be especially the case around capital raising announcements since then financial details of the company are published and discussed at, for example road-shows around the new issuance. Therefore, we move on to a second methodology taking into account idiosyncratic movements.

3.3 Model-Based Performance

As experienced by all CoCo investors, the difficulty in these financial products lies in their different characteristics which are hard to compare like the trigger type, conversion type, maturity, coupon cancellation, and so on. However, the implied barrier methodology can be used as a tool to compare CoCos with different characteristics. In this second approach, we will use the implied barrier to derive theoretical values for the outstanding CoCos under the assumption of no impact by the new CoCo issuance and compare them with the actual market values.

3.3.1 Method

The implied barrier can be interpreted as the stock price level (assumed by the market) that is hit (for the first time) when the CoCo gets converted or written down. If nothing changes, the market will keep the same idea about the implied barrier level and hence result in a constant implied barrier over time. In other words, when there is no impact due to this new CoCo, no change could theoretically be observed in the implied barrier. As such we can see in the levels of the implied barrier if there is an impact due to the announced new CoCo. This leads us easily to the second approach of our impact analysis. As an example, we show the implied barriers of the two outstanding CoCos of ACAFP from the previous section in Fig. 3a.

As from the previous section, the implied barriers can be translated into CoCo quotes. The theoretical CoCo price does not take any information of a new CoCo issuance into account by assuming a constant implied barrier. These values can be used as our reference. Any change in the market compared with this reference, is then due to the impact of the announcement of a new CoCo issuance. As such we can calculate the theoretical CoCo prices from a constant implied barrier and compare them with the market values. The results of our CoCo examples are shown in Fig. 3b. As a last step, we define cheapness as the difference between the market CoCo return and the theoretical CoCo return until the announcement date. In Fig. 3, the cheapness of the two outstanding CoCos of Crédit Agricole is shown.

3.3.2 Results

An overall view is derived for the cheapness by averaging the differences in theoretical and market CoCo prices for each outstanding CoCo during the observation period of the new CoCo. We averaged the differences of all the CoCos on one day until five days after the announcement and also on the issue date of the new CoCo (Table 3).

Clearly, from Fig. 4, on average the cheapness on each day of our observation period is negative, meaning that market price is below the theoretical price assuming no impact. As such we conclude also from this approach that there is a negative impact of about 42 bps on average on the outstanding CoCos when a new CoCo issuance is announced.

4 Impact After Issue Date

At this point, we investigated the impact of a new CoCo issuance between the announcement and issue date. In this section, we show the results for a longer observation period. More concrete, both analyses are extended to 10 trading days after the issue date.

From our first analysis, where we compare the outstanding CoCos with the CoCo indices, a downward trending impact is observed in Fig. 5a. The second analysis which compares the market and model prices of the outstanding CoCos is shown in Fig. 5b. In both analyses, the negative impact gets more significant after the issue dates. Hence until 10 trading days after the issue date, there is still a negative impact observable.

5 Conclusion

The price performance of outstanding CoCos was investigated after a new CoCo issue is announced by the same issuer. Based on two approaches, we estimated the price impact on the outstanding CoCos. The first method compared returns of the outstanding CoCos with some overall CoCo indices. As a conclusion, we found that the return of the outstanding CoCos, during the period between announcement and issuance, was slightly lower than the returns of the CoCo indices. There was an underperformance of about 22 bps compared with the Credit Suisse index and about 42 bps with the Merrill Lynch index (although with relative high standard deviations). Since this first study did not take idiosyncratic movements into account, we used also a second method based on the equity derivatives model for CoCos. In this method we compared the actual market performance of the outstanding CoCo bonds with a theoretical model performance taking into account idiosyncratic effects, like movements in the underlying stock, credit default spreads and volatilities. This second approach also concludes that the averaged market returns of the outstanding CoCos were about 42 bps lower than one would expect in case of no influence.

In total, we investigate 24 cases of new CoCo bond issues. The main conclusion of the investigation is that there is a moderated negative effect on outstanding CoCo bonds. This is confirmed by both methodologies and the impact is an underperformance of about 20–40 bps on average in between the announcement date and the issue date. During the period of 10 trading days after the issue date, an extra decrease of 40 bps was observed.

Notes

- 1.

Source: Bloomberg.

References

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision: Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems. Bank for International Settlements, Dec. 2010

European Commision: Possible Further Changes to the Capital Requirements Directive. Working Document. Commission Services Staff (2010)

Akigbe, A., Easterwood, J.C., Pettit, R.R.: Wealth effects of corporate debt issues: the impact of issuer motivations. Financ. Manag. 26(1), 32–47 (1997)

Pennacchi, G.: A Structural Model of Contingent Bank Capital (2010)

Pennacchi, G., Vermaelen, T., Wolff, C.: Contingent capital: the case for COERCs. INSEAD. Working paper (2010)

De Spiegeleer, J., Schoutens, W.: Contingent convertible contingent convertibles: a derivative approach. J. Deriv. (2012)

De Spiegeleer, J., Schoutens, W., Van Hulle, C.: The Handbook of Hybrid Securities: Convertible Bonds, CoCo Bonds and Bail-in. Wiley, New York (2014), Chap. 3

Corcuera, J.M., De Spiegeleer, J., Ferreiro-Castilla, A., Kyprianou, A.E., Madan, D.B., Schoutens, W.: Pricing of contingent convertibles under smile conform models. J. Credit Risk 9(3), 121–140 (2013)

De Spiegeleer, J., Forys, M., Marquet, I., Schoutens, W.: The Impact of Skew on the Pricing of CoCo Bonds. Available on SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2418150 (2014)

De Spiegeleer, J., Marquet, I., Schoutens, W.: CoCo Bonds and Implied CET1 Volatility. Available on SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2575558 (2015)

De Spiegeleer, J., Schoutens, W.: Steering a bank around a death spiral: multiple Trigger CoCos. Wilmott Mag. 2012(59), 62–69 (2012)

De Spiegeleer, J., Schoutens, W.: CoCo Bonds with Extension Risk (2014)

Corcuera, J.M., De Spiegeleer, J., Fajardo, J., Jönsson, H., Schoutens, W., Valdivia, A.: Close form pricing formulas for CoCa CoCos. J. Bank. Financ. (2014)

De Spiegeleer, J., Schoutens, W.: Multiple Trigger CoCos: contingent debt without death spiral risk. Financ. Mark. Inst. Instr. 22(2) (2013)

Cheridito, P., Zhikai, X.: A reduced form CoCo model with deterministic conversion intensity. Available on SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2254403 (2013)

Madan, D.B., Schoutens, W.: Conic coconuts: the pricing of contingent capital notes using conic finance. Math. Financ. Econ. 4(2), 87–106 (2011)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Robert Van Kleeck and Michael Hünseler for useful discussions on the topic.

The KPMG Center of Excellence in Risk Management is acknowledged for organizing the conference “Challenges in Derivatives Markets - Fixed Income Modeling, Valuation Adjustments, Risk Management, and Regulation”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, a link is provided to the Creative Commons license and any changes made are indicated.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

De Spiegeleer, J., Höcht, S., Marquet, I., Schoutens, W. (2016). The Impact of a New CoCo Issuance on the Price Performance of Outstanding CoCos. In: Glau, K., Grbac, Z., Scherer, M., Zagst, R. (eds) Innovations in Derivatives Markets. Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics, vol 165. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33446-2_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-33446-2_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-33445-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-33446-2

eBook Packages: Mathematics and StatisticsMathematics and Statistics (R0)