Abstract

In this chapter, we look at unmarried cohabitation in Canada with a focus on regional differences. The high level of unmarried cohabitation in Quebec is known since the 1980s. Consequently, a substantial part of the research on unmarried cohabitation in Canada has actually focused on Quebec, and most of the research that has not focused on Quebec has dealt with Canada as a single unit. We use data from census and two surveys to examine the individual factors that could explain the differences in the spread of unmarried cohabitation between Quebec and the rest of Canada. Analyses lead to conclude that the differences arise from the institutional settings rather than being related to individual characteristics. Quebec law uses unmarried cohabitation and marriage to accommodate two competing views of gender equality—one that rests on the assumption that spouses should be as economically independent as possible during and after marriage, while the other contends that equality implies dependence even after separation or divorce—whereas in the rest of Canada, law implements only the second one, more in marriage, but also in unmarried cohabitation. The analyses also point to differences within English Canada that, as far as we know, had not been noticed in previous research: unmarried cohabitation seems to be more common in Eastern Canada than in Western Canada, which might be related to immigration.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

Canada is a federation of ten provinces and, nowadays, three territories. Most of the population lives in the provinces. Table 3.1 shows the proportion of women cohabiting among women aged 15–49 living in a marital union in 1986, 1996 and 2006. This proportion has increased over time in all provinces and territories. The spread of unmarried cohabitation was larger from 1986 to 1996 than from 1996 to 2006. The increase has been more important in Quebec and in the territories. This conjugal arrangement remains more common in Quebec than elsewhere in Canada.

There is scarce research on unmarried cohabitation in the territories. A large fraction of their inhabitants are First Nations members. Most other inhabitants are people coming from other parts of the country who live there, usually for their work, for a limited time. The level of unmarried cohabitation has increased in the territories between 1986 and 2006; thus, the current level cannot easily be explained by the persistence of pre-European customs among members of First Nations. Part of the increase may be due to the increase of the proportion cohabiting among the people from the First Nations, maybe linked to the demise of Christian influence. Part may be due to an increase in the proportion cohabitating among people coming from other parts of Canada. In the latter case, unmarried cohabitation could be associated with internal migration and the fact that some of the people who live temporarily in the territories may find cohabitation better suited to their transitory situation than marriage.

The high level of unmarried cohabitation in Quebec is known since the 1980s. Consequently, a substantial part of the research on unmarried cohabitation in Canada has actually focused on Quebec. Most of the research that has not focused on Quebec has dealt with Canada as a single unit, with little attention to regional differences, and with the assumption that, outside Quebec, the spread and meaning of cohabitation are similar to what they are in the United States.

In this chapter, we look at unmarried cohabitation in Canada with a stress on regional differences. We begin with a review of previous research and an overview of the legal context of marriage and unmarried cohabitation in Canada. We use census data from 1986, 1996 and 2006 to explore the relations between age, education and unmarried cohabitation within the provinces and territories.

We then use data from census and two surveys to examine the individual factors that could explain the differences in the spread of unmarried cohabitation between Quebec and the rest of Canada. Analyses lead to conclude that the differences arise from the institutional settings rather than being related to individual characteristics. Quebec law uses unmarried cohabitation and marriage to accommodate two competing views of gender equality—one that rests on the assumption that spouses should be as economically independent as possible during and after marriage, while the other contends that equality implies dependence even after separation or divorce—whereas in the rest of Canada, law implements only the second one, more in marriage, but also in unmarried cohabitation.

The analyses also point to differences within English Canada that, as far as we know, had not been noticed in previous research: unmarried cohabitation seems to be more common in Eastern Canada than in Western Canada, which might be related to immigration.

2 Terminology: Language Matters

According to official demographic terminology, there are two kinds of marital unions: marriage and consensual union.Footnote 1 Marriage is typically solemnized and registered; consensual union is typically neither solemnized nor registered. Both are stable forms of relationships that involve cohabitation and both may have civil effects.

Sociologists and demographers routinely use the word “cohabitation” to refer to unmarried cohabitation, and “marital union” as a synonym of “marriage”. Using “cohabitation” for “unmarried cohabitation” seems to have roots in early modern studies on college students living together without being married. In today’s parlance, this was a form of transitory room sharing with benefits that might or might not have led to marriage, but obviously not a substitute for marriage (e.g. Macklin 1972). It was dubbed “premarital cohabitation” and, at some point, for convenience or otherwise, it became shortened to “cohabitation”.

Recently, “partner” and “partnership” have become common in English-speaking literature on unmarried cohabitation, but their meaning is uncertain. At times, partnership is used for what is “marital union” in the dictionaries, and there are two types of “partnership”: marriage and “cohabitation”. At times, “partnership” means unmarried cohabitation, maybe with a nuance of stability; in such a case, there is no word for the larger category of “marital union”.

Things would be less confusing if demographers abided by their dictionaries. They would allow brevity to anyone writing about Canada. Everything relevant would fit in two sentences:

-

In Canada, consensual union is a legal institution.

-

Canadian demographers do not abide by the dictionaries: they use “common-law union” for consensual union in English, and “union libre” in French.

3 Previous Research

Anecdotal evidence suggested that by the end of the 1970s, unmarried cohabitation was no more an isolated phenomenon in Canada. In the 1981 Census, Statistics Canada attempted to enumerate unmarried partners by instructing them to answer the question on the relation to the head of the household as if they were husband or wife. Spouses were to be distinguished from unmarried partners using marital status. Given that, at any time, some unmarried partners are still married to their “former” spouse, this strategy led to the misclassification of such individuals and the underestimation of unmarried partners (Dumas and Bélanger 1996). The 1986 Census used the same strategy, but since 1991, the Census form uses different categories for spouses and unmarried partners in the question on the relation to the head of the household, as well as a direct question on living or not in a common-law union, separate from the question on marital status.

In 1984, a research team led by academics and funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council conducted the National Fertility Survey, the first biographical survey of family events carried out using a probabilistic sample of the Canadian population (Balakrishnan et al. 1993). The same year, Statistics Canada conducted a somewhat similar survey, the Family History Survey (Burch and Madan 1986). Since then, Statistics Canada has conducted retrospective biographical surveys on family events in 1990, 1995, 2001, 2006 and 2011 as part of its General Social Survey program. Much if not most of the demographic research on unmarried cohabitation in Canada has been done using either census data or data from these biographical surveys.

Some of the research published in the 1990s—such as Dumas and Péron (1992), Balakrishnan et al. (1993) and Dumas and Bélanger (1996)—focused on documenting the rise of unmarried cohabitation. The main finding was that “living common-law” was more widespread in Quebec that in the rest of Canada. Others looked more specifically at the relation between living in a common-law union and sociodemographic characteristics (Turcotte and Bélanger 1997; Turcotte and Goldscheider 1998; Bélanger and Turcotte 1999). Kerr et al. (2006) conducted the most recent study of this type, which confirmed what had emerged over the previous decade or so: unmarried cohabitation is associated with lower social status in English-speaking provinces, but not in Quebec.

Given these results, it is no surprise that Quebec demographers got interested in the “meaning of cohabitation”. Early research investigated whether unmarried cohabitation was a prelude to marriage or an alternative to marriage, without providing a definitive answer (Lapierre-Adamcyk et al. 1987; Lapierre-Adamcyk 1989). Several years later, it had become clear that, at least in Quebec, unmarried cohabitation was not just premarital cohabitation (Le Bourdais and Marcil-Gratton 1996; Le Bourdais and Neill 1998; Le Bourdais et al. 2000; Le Bourdais and Lapierre-Adamcyk 2004). Comparative research showed that unmarried couples stayed together longer in Quebec than in Ontario, and were less prone to marry (Le Bourdais and Marcil-Gratton 1996; Lapierre-Adamcyk et al. 1999). Comparative research also showed differences in values. In Quebec, young people favoured values pointing towards a redefinition of the conjugal union: compared to young people from Ontario, they gave less importance to a stable couple relationship, less importance to marriage as a source of happiness, and more importance to work (Lapierre-Adamcyk et al. 1999). Péron (2003) summed up this line of research in the title of a book chapter he wrote on nuptiality in Quebec, stating that from the beginning to the end of the twentieth century, marriage went from being a necessity to being an option. Lachapelle (2007) added one important nuance to this synthesis: unmarried cohabitation is not more common in Quebec than in the rest of Canada, it is more common among French-speaking Quebeckers than among other Canadians.

Given that from the 1970s to the end of the 1990s, fertility had plummeted in Quebec, some looked into the relation between the diffusion of unmarried cohabitation and the decrease of fertility. The prevailing view was that Quebec low fertility was caused by Quebeckers’ fondness for cohabitation. Rochon (1989) found that within age groups, women who live or have lived in common-law union had fewer children, on average, than women who were married or had been married. According to Caldwell (1991) and Caldwell et al. (1994), the high proportion of Quebec women living in a common-law union and the instability of their chosen form of union explained their high level of childlessness. Dumas and Bélanger (1998) concluded that fertility is lower within common-law union than within marriage. Krull and Trovato (2003) found that low marriage rates among Quebec women were a key factor of Quebec low fertility in the 1990s. Lapierre-Adamcyk and Lussier (2003) also found that the overall impact of unmarried cohabitation in Quebec was to reduce general fertility. Caron-Malenfant and Bélanger (2006: 88) reported results in which fertility was lower for women living in a common-law union than for married women. This line of research ended recently, probably because since the mid-2000s, the TFR is higher in Quebec than in Ontario. The new difference is interpreted as an effect of family policies: the public provision of parental leave and childcare is more generous in Quebec than in Ontario (Beaujot et al. 2013). Interestingly, such an explanation assumes implicitly that fertility may be as high within unmarried cohabitation as within marriage, and that unmarried partners may be as responsive to policies as spouses. Recent work by Laplante and Fostik (2015) shows that among French-speaking Quebeckers, consensual union has become the main locus of fertility.

Recent research takes unmarried cohabitation as a given. Lachance-Grzela and Bouchard (2009) find little differences in the quality of the relationship between unmarried partners and spouses in Quebec. Laplante and Flick (2010) found that in Ontario, reported measures of health were significantly lower among unmarried partners than among spouses, but found little differences between the two groups in Quebec. Lardoux and Pelletier (2012) found that, in Quebec, having unmarried parents has no negative effect on educational outcomes for boys, and a positive outcome for girls.

Much of the research on unmarried cohabitation in Canada has focused on Quebec. Quebec demographers know the American literature and cite it, but they also know the French literature and it is no surprise that, on this topic, they seem to find more similarities between Quebec and France than between Quebec and the USA. The article by Villeneuve-Gokalp (1990), in which the diffusion of unmarried cohabitation in France in the1980s is documented, is widely cited by them. More recently, studies on the use, by opposite-sex couples, of PACS,—a form of “dependence free” registered partnership originally designed for same-sex couples—has attracted some interest for its practical similarity with common-law union (on PACS, see Rault 2009).

Some of the research on unmarried cohabitation in Canada as a whole has been done with an eye on the American experience. From this perspective, unmarried cohabitation is considered something that delays marriage, or a step in the formation of a new marriage after divorce. Pollard and Wu (1998), Wu (1995, 1996, 1999) as well as Wu and Balakrishnan (1995) are typical examples of this approach, in which “cohabitation” in Canada appears to be similar to “cohabitation” in the USA, once admitted that things are different in Quebec. Wu (2000) concludes the book in which he summed up the research he conducted in the 1990s by pleading for a legal framework of common-law union that would give it the same civil effects as marriage especially for the sharing of assets and spousal support.

The current dominant view is that in Quebec, or more precisely among French-speaking Quebeckers, living in a consensual union is as normal or mainstream as it is in France or in the Nordic countries, whereas outside Quebec and among non-French-speaking Quebeckers, it is either a convenient transient state for young adults or an alternative form of marriage for the poor, pretty much as it is held to be in the USA.

4 Legal Context

The regional differences in the spread of unmarried cohabitation across Canada are closely related to differences in legal systems. Canada is a federation formed by grouping together, from 1867 onwards, the British possessions in North America. Newfoundland, in 1949, was the last British colony to become a Canadian province. According to the 1867 Constitution, the federal Parliament has exclusive legislative authority over “Marriage and divorce”, whereas “the solemnization of marriage in the province” and “property and civil rights in the province” fall under the jurisdiction of each province. The legislative authority of the federal Parliament on marriage is limited to impediments. “Property and civil rights” include much of family law, especially marital property. The authority of the federal Parliament over divorce has been interpreted by the courts as including spousal support, child custody and support, as well as the grounds for divorce. However, judicial separation and annulment, which have consequences very similar to those of divorce, fall under provincial jurisdiction. All Canadian provinces have inherited English common law as the basis of their private law, except Quebec whose private law is based on French civil law.

The difference between Quebec and the rest of Canada involves language and religion as much as law. Quebec was predominantly Catholic whereas the rest of Canada, with the exception of Newfoundland and Labrador, was mainly Protestant. About 80 % of Quebeckers speak French as their first language, whereas English is the first or main language of the vast majority of the population in all other provinces and territories, except New-Brunswick, where French is the first language for a large fraction of the population and which is the only officially bilingual province. However, although language and the relation to religion are essential to understand how cohabitation may have become so widespread in Quebec, the values and mechanism that support cohabitation in Quebec nowadays are embodied in law and are best understood by focusing on legal issues.

Until 1969, divorce, although falling under federal jurisdiction since 1867, was actually regulated by the law as it existed in each province before 1867. Former colonies which had allowed courts to grant divorce before 1867 kept allowing it, whereas in the other provinces, such as Ontario and Quebec, divorce had to be granted by a private bill from the federal Parliament, as in the UK until 1857. In 1968, the federal Parliament passed the Divorce Act (S.C. 1967–8, c. 24), enforcing the same provisions for all of Canada. From that moment, divorce was granted by courts in all of Canada and became an important feature of family law and, so to speak, of everyday life.

As seen in Table 3.1, common-law union became statistically noticeable in the 1980s. Although common-law union remains limited in spread in English Canada, the legal situation of unmarried couples and their children was dealt with by the federal Parliament, the provincial legislatures and the courts. A series of rulings of the Supreme Court, changes in status law in the common-law provinces and to status law and the Civil Code in Quebec progressively reduced the differences between married and unmarried couples. In their dealings with the State and with third parties (employers, insurance companies, etc.), married and unmarried couples are treated in the same way. Legal rights and obligations between parents and children depend solely on filiation, not on the circumstances of birth. Furthermore, Canada’s welfare system is a mix of the liberal and the Nordic welfare regimes and, as in the Nordic welfare state regime, social rights largely depend on individual characteristics and not on marital status. Having access to health insurance or favourable taxation are no more incentives for marriage in Canada than in the Nordic countries (see Andersson et al. 2006). The legal recognition of consensual union is extended to foreigners: Canadian immigration law handles in the same way married couples and couples living in a consensual union. As we saw earlier, Statistics Canada gathers and publishes information on consensual unions since the 1980s, using the terms “common-law union” in English and “union libre” in French. The remaining legal differences between married and unmarried couples are mainly limited to the degree of economic dependence between the two persons who live together, and they are a consequence of competing visions of individual autonomy within the couple rather than a form of discrimination. In Canada, consensual union has become a social and a legal institution.

The prevailing view in the English-speaking provinces is that marriage is a relation based on mutual dependence. Within marriage, gender equality is best defined relative to divorce and implies the equal sharing of assets and spousal support that ideally allow the economically dependent spouse to maintain her standard of living. In principle, the same should apply to common-law union. In all common law provinces, legislatures have passed statutes on “domestic relations” that govern the economic relations between the spouses or partners, with some freedom to write agreements on the sharing of assets, the extent of the freedom being typically greater for partners than for spouses.

In Quebec, there are two competing views of what should be gender equality within the couple: the one that is prevailing in the English-speaking provinces, and one that says that gender equality first implies economic independence. According to the second view, property should be separate as a principle, spouses and partners being free to write down whatever agreement suits them best, and spousal support should not exist. The strength of the two competing views eventually led the Quebec government to implement a system that accommodates both, but significantly altered the meaning of marriage. Allowing spouses to keep their property separate if they wished so, and to write whatever contractual agreements suit them best had been a traditional feature of French and Quebec law. However, the Quebec government redrew marriage in such a way that, for most practical purposes, assets earned once married are deemed common and are split equally upon divorce; furthermore, private agreements that depart from that rule are void. From contemporary documents (e.g. CSF 1978, 1986), it was clear from the beginning that with such a redefinition of marriage, common-law union, which was already attracting many, should become the legal form of marital union for couples who want their relation based on economic independence. This was a drastic change, but was met with very little opposition.

How it became almost natural to implement a legal solution that would literally push a large fraction of the population away from marriage in a province traditionally as close to the Catholic Church as, say, Ireland or Poland, is dealt with in Laplante (2006, 2014) and Laplante et al. (2006). Basically, the French-speaking Catholics broke away from the Church almost instantly at the end of the 1960s, after a decade of rapid and deep social change. The Humanae Vitae encyclical, in which the Church restated its ban on contraception, acted as a catalyst. Until 1968, in Quebec, marriage had to be solemnized by a priest or some other religious minister and, despite all civil effects of marriage being detailed in the Civil Code, the common view was that marriage was a religious institution. The depth of the social change, the rise of feminism and the flurry of new issues related to sex and the family on which the Church was perceived as disconnected from modernity—divorce, abortion, homosexuality—debased the Catholic doctrine. Marriage became optional in this context. The process may have been similar to the one that led to the loss of meaning of marriage in East Germany after the rapid and deep changes that followed German reunification (Perelli-Harris et al. 2014).

Currently, in Quebec, spouses and unmarried partners receive equal treatment by the State and third parties, and children have equal rights in all respects whether or not their parents are married. The differences between spouses and unmarried partners are in the sharing of property and the right to spousal support after the breakdown of the union. Unmarried partners may keep all their property separate if they wish so, as spouses could do until 1989. Unmarried partners are not entitled to “spousal” support from a former partner. As before 1989, spouses may choose between two matrimonial regimes: separation as to property or partnership of acquests. However, since 1989, even for spouses who chose separation as to property, the accrued value of the home and second home, of pensions and retirement savings, the cars used by the family, the furniture and some others assets are shared equally upon separation or divorce. Whatever the matrimonial regime, spouses are entitled to spousal support after separation or divorce. Since 1989, separation as to property has little other use than allowing spouses to maintain their businesses assets separate.

The Quebec legal “balance” between the two competing views of gender equality has been challenged in court. The case opposed a former unmarried partner—born in a Latin American country where, under some circumstances, consensual union has all the civil effects as marriage—to one of Quebec most successful and richest businessmen. She asked for spousal support and the equal sharing of assets as if she had been married under the regime of partnership of acquests—something rather unlikely for married couples comprising a prominent businessperson. Given the Canadian legal context, to get in court, the case had to be framed as a form of discrimination. Not imposing the sharing of assets and the entitlement to spousal support to unmarried partners was thus argued to be a form of discrimination against unmarried partners.

Given the stakes, several third parties were involved, including the Quebec government, which insisted on keeping the balance it had painstakingly achieved in 1989. Interestingly, both the plaintiff and the Quebec government used demographers as experts. Thus, Céline Le Bourdais and Évelyne Lapierre-Adamcyk wrote reports and testified as experts for the Quebec government whereas Zheng Wu did so for the plaintiff.

The case was heard by the Supreme Court, which was asked to answer two questions: whether not imposing the sharing of assets and spousal support to unmarried partners was a form of discrimination and, if so, whether it was an acceptable form of discrimination. Five of the nine judges answered “yes” to the first question, and five answered “yes” to the second. The Chief justice is the one who answered “yes” to both (SCC 2013). This decision upheld Quebec law and probably avoided a constitutional crisis. Recently, the Conseil du statut de la femme, the Quebec government agency that advises the government on women’s rights, changed its position. After having advocated during decades for a strong economic dependence between spouses after divorce and freedom in these matters for unmarried partners, it now supports imposing the sharing of assets and “spousal” support for unmarried partners upon and after breakup (CSF 2014).

5 Consensual Union as a Function of Age and Education

Table 3.1 shows that, overall, in all Canadian provinces and territories, the proportion of women living in a marital union who live in a consensual union rather than being married has increased from 1986 to 2006. The question still at the core of most inquiries about the diffusion of consensual union is whether this phenomenon is primarily the outcome of a change in values—an ideational change—or the consequence of a change in the economic conditions of young people.

It is commonly assumed that if the diffusion of consensual union is primarily the consequence of a change in the economic conditions of young people, living in a consensual union should be negatively associated with education: the proportion of women living in a consensual union should be low among highly educated women and remain so across periods.

It is commonly assumed that if the diffusion of consensual union is primarily the outcome of an ideational change, the diffusion of consensual union should start among highly educated women and then spread to the less educated. Thus, living in a consensual union should be positively associated with education at the beginning of the process, and uncorrelated with it at the end, once it has become a socially accepted form of relationship or maybe even a new norm.

In both cases, the proportion of women living in a consensual union should decrease with age. As a “new” pattern of behaviour, it should be more common among the young than among the old and remain so until the end of the diffusion process. Furthermore, given that, over time, a couple may transform its consensual union into a marriage, but not its marriage into a consensual union, the proportion of women living in a consensual union among women living in a marital union should decrease with age even once the diffusion process is over.

Figure 3.1 reports the proportion of women living in a consensual union among women aged between 15 and 49 living in a marital union in each Canadian province and territory in 1986, 1996 and 2006. Looking at this figure leads to four main findings. In most provinces this proportion decreases with age. It increases from one census to the next for all ages in each province and territory. It is higher in Quebec and in the territories than in the rest of Canada. In most provinces and territories, the increase seems to have been larger between 1986 and 1996 than between 1996 and 2006.

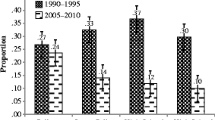

Figures 3.2a, 3.2b, 3.2c, 3.2d, 3.2e and 3.2f allow exploring the relation between consensual union and education. They report the proportion living in a consensual union among women living in a marital union according to level of education within 5-year age classes, for women aged between 20 and 49, in each Canadian province and territory in 1986, 1996 and 2006.

Percent of women living in a consensual union among women aged 20–24 living in a marital union by level of education

Note: < Sec Less than Secondary Completed, Sec Secondary Completed, Post-Sec Post-Secondary Completed, Uni University Completed

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on 1986, 1996, and 2006 Canadian census data

Percent of women living in a consensual union among women aged 25–29 living in a marital union by level of education

Note: < Sec Less than Secondary Completed, Sec Secondary Completed, Post-Sec Post-Secondary Completed, Uni University Completed

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on 1986, 1996, and 2006 Canadian census data

Percent of women living in a consensual union among women aged 30–34 living in a marital union by level of education

Note: < Sec Less than Secondary Completed, Sec Secondary Completed, Post-Sec Post-Secondary Completed, Uni University Completed

Source: Authors’ elabortion based on 1986, 1996, and 2006 Canadian census data

Percent of women living in a consensual union among women aged 35–39 living in a marital union by level of education

Note: < Sec Less than Secondary Completed, Sec Secondary Completed, Post-Sec Post-Secondary Completed, Uni University Completed

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on 1986, 1996, and 2006 Canadian census data

Percent of women living in a consensual union among women aged 40–44 living in a marital union by level of education

Note: < Sec Less than Secondary Completed, Sec Secondary Completed, Post-Sec Post-Secondary Completed, Uni University Completed

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on 1986, 1996, and 2006 Canadian census data

Percent of women living in a consensual union among women aged 45–49 living in a marital union by level of education

Note: < Sec Less than Secondary Completed, Sec Secondary Completed, Post-Sec Post-Secondary Completed, Uni University Completed

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on 1986, 1996, and 2006 Canadian census data

Among women aged 20–24, the proportion is high, it increases from one census to the next and there is no strong relation with education, except in 1996 in Saskatchewan, and in 1996 and 2006 in the Northwest Territories, where the proportion decreases as the level of education increases. In 2006, the levels are higher in Eastern Canada—Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Quebec—than in Western Canada—Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia.

Among women aged 25–29, the proportion is still high, but lower than among women aged 20–24. It increases from one census to the next. It is higher in Eastern Canada than in Western Canada, much higher in Quebec than in the other provinces, much higher in the territories than in all provinces but Quebec. In 2006, the proportion slightly decreases as the level of education increases in most provinces and territories, but clearly not in Quebec where there is no apparent relation between consensual union and education.

Among women aged 30–34, the proportion is still lower than among women aged 25–29. It tends to be higher in Eastern Canada than in Western Canada, even higher in the territories, and higher still in Quebec. In 2006, the proportion decreases as education increases, but the slope varies across provinces and territories, tending to be larger where the proportion is higher, except in Quebec where the slope is small despite the proportions being high. Among women aged 35–39, the proportion is lower. It tends to be higher in Eastern Canada than in Western Canada, again higher in the territories and still higher in Quebec. In 2006, the proportion decreases as education increases in the same fashion as among women aged 30–34. The levels are still lower among women aged 40–44, in all provinces but Quebec. They are higher in the territories; in 2006, in the territories, the association between consensual union and education appears to be strong. In Quebec, the proportion is higher and, in 2006, there is no clear relation between consensual union and education.

One final fact is worth noting. In Quebec, in 1986, the proportion of women living in a consensual union slightly increases as the level of education increases among women 25–29 and 30–34. Something similar can be seen among women aged 40–44 in 1996.

In Quebec, the pattern suggests that the diffusion of consensual union is the outcome of an ideational change. The proportion of women living in a consensual union is slightly higher among educated women in what could have been “leading” cohorts. In recent censuses, the proportion is high even among women aged between 40 and 44, with little variation across education levels.

Things are different in the rest of Canada. Despite interesting regional differences between East and West and between provinces and territories, the overall pattern is quite similar. The proportion of women living in a consensual union is comparatively high among young women, aged between 20 and 29, with little variation across education levels. The proportion is lower among older women, and decreases as education increases. The diffusion of consensual union among the young can be interpreted as the outcome of an ideational change allowing transitory relations similar to those of the 1970s college students. Among women aged over 30, the association between consensual union and education is consistent with an explanation involving the economic condition of the individuals.

Phrased this way, such an interpretation would lead to conclude that there has been little relation between the change in the economic conditions of the young, from 1976 onwards, and the diffusion of consensual union. Looking at the context offers a slightly alternative view in which the change in the economic conditions of the youth and the diffusion of consensual union as their preferred from of marital relationship are related through their common dependence on a more fundamental change.

Figure 3.3 reports the evolution of the median market income according to age class and sex for men and women aged 20–24 and 25 to 34 in Canada from1976 to 2011, expressed in thousands of Canadian 2011 constant dollars. Between 1976 and 1996, the real median income of young men and women aged 20–24 decreased annually by an average rate of 3.58 % and 3.44 % respectively, whereas the real median income of men aged 25–34 decreased annually by 1.83 % and the real median income of women of the same age class remained stable. From 1996 onwards, the real median income of all groups have been increasing by almost 1.5 % a year, except for men aged 25–35 for which the increase has been close to 1 %.

Median market income according to age and sex, men and women aged 20–24 and 25–34. Canada, 1976–2011 (Thousands of Canadian 2011 constant dollars)

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, CANSIM table 202-0407 (Income of individuals, by sex, age group and income source, 2011 constant dollars)

Although some other interpretation may be possible, from a demographic perspective, the decrease in the income of young men and women aged 20–24 is likely to be related the postponement of the transition to adulthood. Between 1976 and 1996, the proportion of men and women aged 20–24 engaged in postsecondary education has increased, leading to the decrease in median income, either because some do not have any market income at all, or because their market income comes from part time work or seasonal work combined with college or university attendance. From this perspective, living in a consensual union may be seen as associated with low income, but the association is somewhat spurious. Low income and potentially transitional marital relationship are likely two markers, outcomes or consequences of the postponement of the transition to adulthood. In other words, low income is likely not the cause of the prevalence of consensual union among the young. Apparently the diffusion of the postponement of adulthood ended around 1996. Since then, the median income of both men and women aged 20–24 has increased slowly, but steadily, likely because the proportion enrolled in postsecondary education has reached a plateau.

The evolution of the median income of men and women aged 25–34 tells a somewhat different story. The decrease in the real median wage of men is likely a consequence of the postponement of the transition to adulthood. Still in the 1970s, men were expected to have “real” jobs providing a real male breadwinner income, whereas women were not yet expected to work full time or even at all once married. Between 1976 and 1996, this has changed, more men becoming enrolled in postsecondary education in their late 20s and even early 30s, and more women adopting patterns similar to those of the men of the same age.

If this interpretation is correct, the diffusion of consensual union among the Canadian youth outside Quebec could be interpreted mainly as a consequence of the postponement of the transition to adulthood in a world that accepts marital relationships outside of marriage. The limited diffusion of consensual union among women aged at least 30 and its negative association with education would mean that after age 30, consensual union is somehow related with lower social status or lower economic conditions.

In Quebec, the postponement of adulthood is likely to have been related with the diffusion of consensual union among the young in the same way as in the rest of Canada, but the ideational change has been deeper and consensual union has become a mainstream form of marital union for women aged 30 or more. The narrowing difference between the real median income of men and women aged 25–34, which does not seem to be related to the diffusion of consensual union outside Quebec, is likely to have been a key factor in Quebec. More equal incomes across genders, and likely within many couples, have empowered women in a way that made them economically independent and thus favoured a form of marital union that does not enforce economic dependence between the partners. This did not happen in the rest of Canada, but it is consistent with the conception of gender equality within the couple on which the current Quebec legislation on consensual union is based.

6 Hypotheses

Consensual union is more common in Quebec than in the rest of Canada. The association between living in a consensual union, age and education is weak to non-existent in Quebec, but clear in the rest of Canada. The evolution of the median income of young men and women during the years from 1976 onwards and the pattern of the relation between living in a consensual union and age and education suggest that outside Quebec, consensual union is a widespread form of marital relationship, likely transitory, for the young, and a “cheap” form of marriage for people aged at least 30. In Quebec, consensual union among the young may be hard to distinguish from consensual union among the young in the rest of Canada; however, among women aged at least 30, it is not related to lower education, but, given the legal context and what is known from previous research, likely to be related with independence and gender equality within the couple. If this is true, economically independent women should be more likely to live in a consensual union than being married in Quebec, but not in the rest of Canada. Furthermore, favouring values related with individual autonomy should increase the probability of living in a consensual union rather than being married in Quebec, but not in the rest of Canada, or, at least, not as much in the rest of Canada as in Quebec. We perform three analyses related to these hypotheses.

In the first one, we focus on the economic role of the woman in the couple. We use being the main source of income in the family, combined with labour force status, as an indicator of one aspect of the level of economic independence of women. We expect women who are the main source of income in their family and are in the labour force to be more likely to live in a consensual union rather than being married in Quebec, but not as much or less so in the rest of Canada.

In the second analysis, we focus on the effect of the level of individual economic security provided by the job. We use holding a job in the public sector, in the private sector, being self-employed or being out of the labour force as an ordinal proxy of the level of economic security. In Canada, typically although not universally, jobs in the public sector are more stable and provide a higher level of social protection than jobs in the private sector. Obviously, the self-employed get less protection from their job than the employed. People out of the labour force are the most economically insecure. Previous research and the legal context of consensual union and marriage suggest that, in Quebec, consensual union could be used by some women as a way to ensure their independence during and after their marital union, whereas marriage could be used by other women as a strategy to secure resources in the event of the breakdown of their union. If this were true, the probability of living in a consensual union rather than being married should increase as the level of job-related economic security increases. There should not be such an effect in the other provinces. Given the nature of the hypothesis, we estimate similar equations for men.

In the third analysis, we focus on the role of values. Data on values are scarce in Canada. We use the limited data available on Canada in the World Value Surveys aggregate sample to study the effect of the level of the importance given to the autonomy of the individual on the probability of living in a consensual union rather than being married. We expect the probability of living in a consensual union to increase with the importance given to autonomy in Quebec, but not as much or less so in the rest of Canada.

In all analyses, we control for age and education, combining them when the size of the sample makes it possible. Additional controls depend on the availability of data in each source and are detailed in the next section.

7 Data and Methods

7.1 The Economic Role of the Woman in the Couple

In this analysis, we use individual level data from the 20 % sample of the population that filled the “long” form of the Canadian census in 1986, 1996 and 2006. We model the probability of living in a consensual union rather than being married among Canadian women aged 15–49 living in a marital union as a function of a series of characteristics using logistic regression. We estimate separate equations for each province and territory.

We measure the level of economic independence by combining two binary variables: being the main support of the family or not, being in the labour force or not. Combining these two variables defines a gradient of economic independence where being the main support and in the labour force implies the highest level of independence, being the main support and not being in the labour force the second, not being the main support and being in the labour force the third and not being the main support and not being in the labour force the last.

Age is grouped in 5-year classes. Education is measured as the highest level of education completed and grouped in four categories as in the figures: less than secondary, secondary, non-university post-secondary education and university. Preliminary analyses showed that the effect of education varies according to age; we estimate the effect of education within age classes.

The data allow examining the effect of several other relevant factors.

Taken together, having lived previously in Quebec and speaking French form a proxy of having been socialised within French-speaking Quebec, where consensual union is more common; this may have an effect, even for people who reside outside Quebec at the time of census. Having children or not may have an effect on the probability of living in a consensual union. Given that having children while living in a consensual union is more common in Quebec than elsewhere in Canada and that the size of the sample allows it, we combine language, having previously lived in Quebec and having children or not. Taken together, these variables define a series of combinations in which each category has its own effect. We report the results from a model in which these variables are combined as to define such a series.

Census data also allow estimating the effect of belonging to a First Nation.

We use the degree of freedom usually associated with the constant to estimate directly the odds of living in a consensual union rather than being married for each group resulting from the combination of age and education. This allows a direct and easy interpretation of the coefficient: if the coefficient for a given combination of age and education is 1, the base probability of cohabiting rather than being married is .5 If the coefficient is greater than 1, the base probability of cohabiting rather than being married is greater than .5 and if it is less than 1, the base probability of cohabiting rather than being married is less than .5.

The coefficients associated with the other variables are interpreted in the usual way: they increase or decrease the base odds. In the Tables 3.2, 3.3 and 3.4 the reference categories are written besides the name of the variable, between brackets. The reference category for the measure of economic independence is the highest level, “Being the main support and Being in the labour force”. The reference category for the combination of speaking French, having lived in Quebec and having children has been chosen to allow easy contextual interpretation: it is referring to a majority group within each province. Thus it is speaking French, having lived in Quebec and not having children in Quebec, but not speaking French, not having lived in Quebec and not having children in all other provinces and territories.

7.2 The Level of Economic Security

In this analysis, we use data from the 2012 Labour Force Survey (LFS) public use microdata file. This survey is used primarily to estimate the unemployment rate, but includes information on marital union and is the only source of data that includes a variable that allows differentiating employment in the public and the private sectors. The LFS uses rotating panels; we use the January and July samples to avoid using twice the same individuals. As explained in the previous section, we use information on job sector as a gradient of economic security. Thus, we model the probability of living in a consensual union rather than being married among Canadian men and women living in a marital union aged 20–49 as a function of the level of economic security measured through employment status, controlling for age, education and other relevant variables available in the survey: age of the youngest own child in the household and census metropolitan area. The LFS does not provide information on language. We use living or not in the main census metropolitan area (CMA) of the province as a proxy for language: in Quebec, the proportion of French-speaking people is lower in the Montreal CMA than elsewhere the province. We thus expect living in a CMA to decrease the probability of living in a consensual union in Quebec and to have no significant effect in the other provinces. We estimate separate equations for men and women and, given the number of equations, we limit the analysis to the four most populous provinces. We estimate the equations using logistic regression.

7.3 Values

We use data from waves 4 and 5 of the Word Values Survey (World Values Survey Association 2005), the only waves of this survey conducted in Canada. We measure the importance given to the autonomy of the individual using the Inglehart autonomy index (Inglehart 1997). We model the probability of living in a consensual union rather than being married among men and women aged 15–49 living in a marital union as a function of the importance they give to individual autonomy, controlling for age, education and the presence of children. The data allow estimating the effect of the economic role of the respondent in the same fashion as we do in our first analysis. Because of the limited size of the sample, we cannot estimate separate equations for each province. Instead, we estimate separate equations for French Quebec and English Canada. For the same reason, we cannot estimate separate equations for men and women. However, we estimate the effect of the autonomy index and of our proxy of the level of economic independence separately for men and women.

8 Results

8.1 The Economic Role of the Woman in the Couple

Although this analysis focuses on economic independence, the main sources of variation in the probability of living in a consensual union are age and education and we describe their effect first (see Table 3.2). Not surprisingly, the base odds of living in a consensual union rather than being married are higher than 1 for all levels of education among Quebec women up to and including ages 40–44. The coefficient associated with women aged 15–19 and completed university education is less than 1 but not significant, which does not come as a surprise since having completed even a one-year university diploma before age 20 is nearly impossible and the category is almost empty. Despite the odds being higher than 1 in all, but one age class, there is an education gradient within each age class. The base odds decrease with age within each education level.

In Ontario, the base odds are greater than 1 for all education levels in the two youngest groups, and for all education levels but university in the 25–29 group. The base odds are less than 1 for all education levels within older groups with the exception of the “Less than secondary group” among the 30–34. As in Quebec, there is an education gradient within age classes and the base odds decrease with age within each education level. The overall pattern is about the same as in Ontario in all other provinces, although a case could be made that the base odds are consistently higher up to and including age group 25–29 in the Atlantic provinces (Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) than west of Quebec. Table 3.3 reports the coefficients from the combination of age and education transformed into easier-to-read predicted probabilities.

The coefficients associated with the levels of economic independence are ordered according to the hypothesis and significant in Quebec and British Columbia. In Ontario and Alberta, the coefficients are ordered according to the hypothesis, but without a significant difference between the two highest levels. In the remaining provinces, the coefficients are not ordered as expected. In New Brunswick and Saskatchewan, being the main support and out of the labour force is associated with a higher probability of living in a consensual union than being the main support and being in the labour force. In Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and Manitoba, the coefficients point in the same direction, but are not significant. There is no sizeable difference between the coefficients associated with the two lowest categories in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan.

In Quebec, childless French-speaking women from Quebec have the highest odds of living in a consensual union; for these women, having children reduces the odds of cohabitation by about 25 %. The odds are about the same for childless French-speaking women from elsewhere; for these women, having children reduces the odds by about 50 %. The odds of living in a consensual union for childless non-French-speaking women from outside Quebec are about a third of those of childless French-speaking women from Quebec; for these women, having children reduces the odds by about 75 %. The odds for childless non-French-speaking women from Quebec are less than 20 % of those of childless French-speaking women from Quebec; for these women, having children reduces the odds by about 60 %. French-speaking women from Quebec have the highest odds of living in a consensual union and, among them, having children reduces these odds by only 25 %. All other women are less likely to live in a consensual union and; for these women, having children reduces the odds by a much larger proportion.

In Ontario, for non-French-speaking women from somewhere else than Quebec, having children reduces the odds of living in a consensual union by about 60 %. Childless French-speaking women from Quebec have the highest odds, more than four times those of non-French-speaking women from elsewhere; for these women, having children reduces the odds by about 66 %, much more than in Quebec. Childless non-French-speaking women from Quebec and childless French-speaking women from elsewhere have about the same odds of living in a consensual union, roughly 60 % higher than those of non-French-speaking women from somewhere else than Quebec; having children reduces the odds by about 75 % in the first group and by about 60 % in the second group. For French-speaking women from Quebec, having children has a stronger effect in reducing the odds of consensual union in Ontario than in Quebec. Speaking French or coming from Quebec increases the odds for childless women. In all groups, having children reduces them from 60 to 75 %.

Given the small number of French-speaking women and of women coming from Quebec in most provinces outside Quebec, many coefficients are not statistically significant despite their magnitude. In Alberta and British Columbia, where numbers are larger, the structure of the ratios between the coefficients is the same as in Ontario.

In all provinces and territories, belonging to a First nation increases the odds of cohabiting. Interestingly, this effect is smaller in Quebec, where the reference group is childless French-speaking women from Quebec, than in any other province and even than the two territories, where the proportion of the population belonging to a First nation is the highest.

8.2 The Level of Economic Security

The effects of age and education are similar to what we have seen in Table 3.2. As expected, among Quebec women, the odds of living in a consensual union decrease as the level of economic risk increases (see Table 3.4). There is no similar gradient for women in the other provinces, and no similar gradient for men in any province. Women out the labour force are more likely to be married in Alberta and British Columbia. Men out of the labour force are more likely to be married in Alberta, but more likely to be living in a consensual union in British Columbia.

In Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia, for men and women, having children reduces the odds of living in a consensual union by about two thirds, regardless of the age of the children. For Quebec women, the effect of having children decreases as the age of the youngest child increases. There is a similar trend among Quebec men, but not as strong as among women. This could be interpreted either as a consequence of having children while cohabiting still becoming more common in Quebec, or as marriage occurring as a “capstone” event.

In Quebec, but also in Ontario and British Columbia, the odds of living in a consensual union are lower for people living in the main metropolitan census area rather than elsewhere in the province. We were using this variable as a proxy for language and we were expecting it to have such an effect in Quebec, but not in the other provinces.

8.3 Values

The sample is small. Given its limited size, it seems appropriate to provide a description in Table 3.5. Table 3.6 shows that there is no striking difference in the distribution of the autonomy index within sociolinguistic groups and sex. However, Table 3.7 shows a clear association between the level of the index and the proportion living in a consensual union among both men and women in French Quebec.

We estimate three equations (see Table 3.8). In the first one, we look at the effect of economic independence net of those of age, education and the presence of children. In the second one, we estimate the gross effect of the autonomy index for men and women. In the third one, we look at the net effects of economic independence and of the autonomy index net of those of age, education and the presence of children:

-

Equation 1: In English Canada, living in a consensual union is associated with economic independence as hypothesized for women. There is no association for men, except for those who are not the main source of income in their family and are not in the labour force, who are much more likely to live in a consensual union rather than being married. There are no significant coefficients for economic independence in French Quebec, which could be a consequence of the small size of the sample. As expected, the odds of living in a consensual union decrease as age increases in both English Canada and French Quebec. Not surprisingly, they decrease as the level of education increases in English Canada; the coefficients are not significant in French Quebec, but this could be a consequence of the sample size rather than a real lack of association. Having children decreases the odds in English Canada and in French Quebec, apparently more in the latter than in the former.

-

Equation 2: In English Canada, the odds of living in a consensual union do not increase with the value of the index neither for women nor for men. In French Quebec, the odds increase with the value of the autonomy index for men and women, maybe more for men than for women.

-

Equation 3: In English Canada, once controlling for sociodemographic characteristics and economic independence, the effect of the level of autonomy becomes significant: the odds of living in a consensual union increase with the value of the autonomy index for women. There is still no association between the autonomy index and living in a consensual union for men. In French Quebec, the odds increase with the value of the autonomy index for men and women, maybe more for men than for women, as in Equation 2. Thus, they are robust to control by sociodemographic characteristics and especially economic independence.

9 Discussion

Both the descriptive figures and the linear models show that the main sources of variation in the probability of living in a consensual union rather than being married are age, education and the difference between French Quebec and English Canada. Figures 3.2a, 3.2b, 3.2c, 3.2d, 3.2e and 3.2f show that the gross probability of living in a consensual union rather than being married decreases with age, but the pattern is not the same in Quebec and elsewhere in Canada. In Quebec, the proportion living in a consensual union is high, close to 50 %, among women in their late 30s and even early 40s. Elsewhere in Canada, consensual union is not common after the late 20s. Among women aged at least 30, living in a consensual union decreases as education increases in most of Canada, but this relation looks much weaker in Quebec.

Linear models convey similar results. Some of the control variables provide additional understanding. Having children does not decrease the probability of living in a consensual union as much in Quebec as elsewhere in Canada, but, unlike elsewhere in Canada, the probability decreases as the age of the children increases. Given that this effect is net of that of age, it could be the hint of a cohort or period difference: vital statistics show that the proportion of children born to mothers living in a consensual union increased over the years in which these children were born. In Quebec, the net effect of education is larger in the linear models than what the gross effects depicted by Figs. 3.2a, 3.2b, 3.2c, 3.2d, 3.2e and 3.2f would suggest. The apparent paradox is easy to explain: the base odds, or the base probability, of living in a consensual union is so large in Quebec that even a “large” net effect of education does not lead to a sizeable change in the gross effect.

Our main focus was the effect of economic independence, economic security and the importance given to autonomy. We expected all three to increase the probability of living in a consensual union in Quebec and especially among Quebec women, but not as much or not at all elsewhere in Canada. Results basically look as expected. The probability of living in a consensual union is related to the level of economic independence of women as expected in Quebec, but also in British Columbia. In these two provinces, women who are the main source of income are more likely to live in a consensual union. This could be interpreted as an indirect effect of poverty or disadvantage. However, living in a consensual union is clearly related to the level of economic security among Quebec women, but not among men and not elsewhere in Canada. In Quebec, as expected, women who get less economic security from their job use marriage as a form of protection against the consequences of the breakdown of their couple. In Quebec, “women at risk” tend to be married, whereas “empowered women” tend to live in a consensual union. Net of our measure of economic independence—hence, net of their actual situation relative to income and participation—, the importance given to autonomy increases the probability of living in a consensual union among women from English Canada and among men and women in French Quebec.

The difference between French Quebec and English Canada is related to differences in the effects of economic independence, economic security and autonomy, but the differences in the effects of age and education as well as the difference in the net base odds are not altered by controlling the effect of these potential explaining variables. Individual characteristics and their effect do not explain much of the difference between the two sociolinguistic groups. This leads to concluding that the difference between French Quebec and English Canada is institutional, or macrosocial, rather than compositional or microsocial.

The analyses generated two new and unexpected results. First, living in a census metropolitan area does not behave as a proxy for language. Second, outside Quebec, consensual union seems to be more common in Eastern Canada than in Western Canada. As far as we know, this had not been observed yet.

One alternative interpretation of the effect associated with living in a CMA is considering it as a proxy for immigration. Canada has a large influx of international immigration, amounting each year to about 0.75 % of its population. Most immigrants choose to live in Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal. The results we got would suggest that people born abroad and children of immigrants are less likely to live in a consensual union than people born in Canada or born to parents born in Canada.

There is no obvious explanation for the difference between Eastern and Western Canada. One tentative explanation would involve immigration. Few immigrants choose to live in the Atlantic Provinces. Another one would involve a mix of religion and economy. Alberta, and to a lesser extent Saskatchewan, have received a significant influx of religious dissenters from German-speaking countries in the nineteenth century and are nowadays the home of the Canadian religious right. Furthermore, both provinces thrive on oil and offer highly paid blue-collar jobs that allow maintaining the traditional breadwinner-homemaker family model (Beaujot et al. 2013).

10 Conclusion

Family law and, more generally, the legal framework of family life changed in a deep way over the last decades in Canada. In a clearer way than in many other countries, these changes have created a context that provided unmarried couples with a legal institution that is best described as consensual union. While the details vary across provinces and despite larger differences between Quebec and the common law provinces, this is true all across the country. Such legal changes reflect a broad change in values.

This said, unmarried cohabitation did not become widespread in the same way in all of Canada. In all provinces, unmarried cohabitation has become common among women aged less than 30, and its diffusion among the young from the early 1980s onwards may be related to the postponement of the transition to the adulthood. Among women aged 30 or more, outside Quebec, unmarried cohabitation remains uncommon and clearly related to education. In Quebec, and probably more properly in French Quebec, unmarried cohabitation is common among women aged more than 30 and living in a consensual union is not primarily related to education.

The main legal difference between consensual union in Quebec and in the common law provinces is the level of mutual economic dependence the law imposes on the partners. In the common law provinces, consensual union is almost a form of “de facto” marriage. Typically, in the common law provinces, statute law assumes that partners should share some assets and allows the judges to impose “spousal” support after breakdown if circumstances seem to justify it even if both partners had waived their rights to such support in a written contract. In Quebec, marriage and consensual union differ radically in that the former imposes the sharing of assets and the possibility of spousal support, whereas the latter leaves all economic relations between themselves to the partners. Being married or not has more legal and economic consequences in Quebec than in the rest of Canada. As we explained earlier, this feature of Quebec law is related to the coexistence, in the Quebec society, of two different and competing views of gender equality within the couple, one that stresses the pooling and equal sharing of wealth and income and leads to economic dependence—which clearly prevails in the rest of Canada—and one that stresses independence and leads to keeping assets and income separate.

This radical difference between marriage and consensual union in Quebec law shapes a setting in which being married or not is associated with the actual level of dependence. Thus, in Quebec, economically dependent women tend to be married, whereas economically independent women tend to live in a consensual union. Other factors are associated with being married or not in Quebec as in the other provinces—such as the presence of children and education—, but not in the same way or not with the same strength as in the other provinces. The difference between English Canada and French Quebec is macrosocial rather than microsocial, more embedded in the institutions than in the distribution of individual characteristics, not so much related to the distribution of values as they may be recorded in a survey, but more to the values enshrined in the law through the political and legislative process.

This difference is not limited to the spread and use of consensual union. Moving away from traditional Christian doctrine towards a moral based on individual freedom, especially on contested issues, has become a distinctive characteristic of Quebec within Canada. Abortion is legal in Canada, but the provision varies greatly across provinces. Some provinces do not provide any abortion service, whereas Quebec is among the few provinces that provide them through a network of public and not-for-profit clinics; about 22 % of pregnancies end in abortion in Quebec, but only 16.5 % in the rest of Canada (Statistics Canada 2014; CIHI 2013). In early 2014, Quebec’s National Assembly passed an act on end-of-life care that allow terminally-ill patients to require medical aid in dying as in some European countries (NA 2014). It is the first Canadian province to do so.

The main difference in the spread of cohabitation in Canada is the difference between French Quebec and English Canada, but there are other differences. We found two that, as far as we know, had not been noticed before: outside Quebec, unmarried cohabitation seems to be more common in Eastern Canada than in Western Canada; unmarried cohabitation could be more common outside the larger census metropolitan areas than elsewhere. These findings were unexpected and the interpretation we provide is tentative. This said, we suggest that both could be related with immigration. Foreign-born Canadians could prefer marriage over unmarried cohabitation for a variety of reasons, among which—notwithstanding cultural or religious issues—more easily insuring the transmission of their original citizenship to their spouse and offspring. Furthermore, the low proportion of people living in a common-law union in Alberta and Saskatchewan is likely related to the combination of religious conservatism and an oil-based economy. Such interpretations are obviously a matter for further research.

More generally, doing research on unmarried cohabitation in Canada suggests that exploring the differences in the meaning of marriage could help understanding differences in the spread and circumstances of unmarried cohabitation. In common law provinces, there is little legal difference between marriage and consensual union, and this similarity seems to be rooted in a strong consensus on economic dependence being the real meaning of a couple relationship. In Quebec, competing views lead to a large difference in some of the civil effects of marriage and consensual union, and to choices that lead themselves to different outcomes in the event of a breakdown. For migrants and immigrants, marriage may have a very practical meaning that has little to do with romance or culture, and more with legal issues. From this perspective, the association between marriage and education, when it exists, could as well be interpreted as a practical issue. Educated people tend to move across larger labour markets than less educated people, and a couple in which both partners are highly educated is more at risk of being affected by career moves that involve moving across large distances, making difficult choices about who will take the risk of losing his or her job to accommodate the other’s career, or choosing to maintain separate residences in different cities or provinces or even countries. For such couples, marriage may provide a safe and simple way of maintaining the legal status of the relationship and ensure protection in case of a breakdown.

Notes

- 1.

See, for instance, the Multilingual demographic dictionary, 2nd ed. (Liège: Ordina: 1982), or the Population Multilingual Thesaurus, 3rd ed. (Population Information Network, Paris: CICRED: 1993).

References

Andersson, G., Noack, T., Seierstad, A., & Weedon-Fekjær, H. (2006). The demographics of same-sex marriages in Norway and Sweden. Demography, 43(1), 79–98.

Balakrishnan, T. R., Lapierre-Adamcyk, E., & Krotki, K. J. (1993). Family and childbearing in Canada: A demographic analysis. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Beaujot, R., Du, C. J., & Ravanera, Z. (2013). Family policies in Quebec and the rest of Canada: Implications for fertility, child-care, women’s paid work, and child development indicators. Canadian Public Policy, 39(2), 221–240.

Bélanger, A., & Turcotte, P. (1999). L’influence des caractéristiques sociodémographiques sur le début de la vie conjugale des Québécoises. Cahiers québécois de démographie, 28(1–2), 173–197.

Burch, T. K., & Madan, A. K. (1986). Union formation and dissolution: Results from the 1984 family history survey. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. (Catalogue No. 99-963).

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2013). Induced abortions reported in Canada 2012. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information.

Conseil du statut de la Femme. (1978). Pour les Québécoises. Égalité et indépendance. Quebec: Éditeur officiel du Québec.

Conseil du statut de la Femme. (1986). Le partage des biens familiaux en cas de divorce. Quebec: Conseil du statut de la femme.

Conseil du statut de la femme. (2014). Pour une véritable protection juridique des conjointes de fait. Quebec: Conseil du statut de la femme.

Dumas, J., & Bélanger, A. (1996). Common-law unions in Canada at the end of the 20th century. In Demographic situation in Canada (pp. 123–181). Ottawa: Statistics Canada. (Catalogue No. 91-209-XIE).

Dumas J., & Péron, Y. (1992). Marriage and conjugal life in Canada. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. (Catalogue No. 91-534).

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kerr, D., Moyser, M., & Beaujot, R. (2006). Marriage and cohabitation: Demographic and socioeconomic differences in Quebec and Canada. Canadian Studies in Population, 33(1), 83–117.

Lachance-Grzela, M., & Bouchard, G. (2009). La cohabitation et le mariage, deux mondes à part? Un examen des caractéristiques démographiques, individuelles et relationnelles. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 41(1), 37–44.

Lachapelle, R. (2007). La montée des unions de fait. Un phénomène québécois ou francophone? Colloque de l’Association des démographes du Québec, Congrès de l’ACFAS, 7–11 May.

Lapierre-Adamcyk, E. (1989). Le mariage et la famille: mentalités actuelles et comportements récents des femmes canadiennes. In K. J. Krotki, & R. P. Beaujot (Eds.), The family in crisis: A population crisis?/Crise de la famille: crise démographique? (pp. 94–104). Ottawa: Société Royale du Canada.

Lapierre-Adamcyk, É., Balakrishnan, T. R., & Krotki, K. J. (1987). La cohabitation au Québec, prélude ou substitut au mariage? Les attitudes des jeunes Québécoises. In R. B. Dandurand (Ed.), Couples et parents des années quatre-vingt (pp. 27–46). Québec: Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture.

Lapierre-Adamcyk, E., Le Bourdais, C., & Marcil-Gratton, N. (1999). Vivre en couple pour la première fois. La signification du choix de l’union libre au Québec et en Ontario. Cahiers québécois de démographie, 28(1-2), 199–227.

Laplante, B. (2006). The rise of cohabitation in Quebec. Power of religion and power over religion. Canadian Journal of Sociology, 31(1), 1–24.

Laplante, B., & Flick, C. (2010). Le mariage, l’union de fait et la santé des conjoints au Québec et en Ontario. Cahiers québécois de démographie, 39(1), 1–26.

Laplante, B., & Fostik, A. L. (2015). The recent evolution of fertility within marriage and consensual union in two Canadian provinces: Disentangling the Quebec fertility paradox. Canadian Studies in Population, 42(2), 81–101.

Laplante, B., Miller, C., & Malherbe, P. (2006). The evolution of beliefs and opinions on matters related to marriage and sexual behaviour of French-speaking Catholic Quebecers and English-speaking Protestant Ontarians. Canadian Studies in Population, 33(2), 205–235.

Lardoux, S., & Pelletier, D. (2012). Trajectoires conjugales des parents et rendement scolaire des enfants en première année du primaire. Cahiers québécois de démographie, 41(2), 369–412.

Le Bourdais, C., & Lapierre-Adamcyk, E. (2004). Changes in conjugal life in Canada: Is cohabitation progressively replacing marriage? Journal of Marriage and the Family, 66(4), 929–942.

Le Bourdais, C., & Marcil-Gratton, N. (1996). Family transformations across the Canadian/American border: When the laggard becomes the leader. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 27, 415–436.

Le Bourdais, C., & Neill, G. (1998). Are mom and dad married? And does it matter for the future of the family? In Contributions to family demography: Essays in honour of Dr. Wayne W. McVey, Jr. (pp. 75–97). Edmonton: Department of Sociology, University of Alberta.

Le Bourdais, C., Neill, G., & Turcotte, P. (2000). The changing face of conjugal relationships/L’évolution des liens conjugaux. Canadian Social Trends/Tendances sociales canadiennes, 56, 14–17.

Macklin, E. D. (1972). Heterosexual cohabitation among unmarried college students. The Family Coordinator, 21(4), 463–472.

National Assembly. (2014). An act respecting end-of-life care (S.Q. 2014, c. 2). Quebec City: Quebec Official Publisher.

Perelli-Harris, B., Mynarska, M., et al. (2014). Towards a new understanding of cohabitation: Insights from focus group research across Europe and Australia. In Session 212: Cohabitation and marriage, 2014 annual meeting of the Population Association of America (PAA), Boston, USA, 1–3 May.

Péron, Y. (2003). Du mariage obligatoire au mariage facultatif. In V. Piché, & C. Le Bourdais (Eds.), La démographie québécoise. Enjeux du XXI e siècle (pp. 110–143). Montréal: Presses de l’Université de Montréal.

Pollard, M. S., & Wu, Z. (1998). Divergence of marriage patterns in Quebec and elsewhere in Canada. Population and Development Review, 24(2), 329–356.

Rault, W. (2009). L’invention du PACS. Pratiques et symboliques d’une nouvelle forme d’union. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Statistics Canada. (2014). Table 051-0004 - Components of population growth, Canada, provinces and territories, annual (persons). Ottawa: CANSIM (database), Statistics Canada.

Supreme Court of Canada. (2013). Quebec (Attorney General) v. A, 2013 SCC 5, [2013] 1 S.C.R. 61.