Abstract

The first 10 years of the 2000s were the worst decade of job-creating performance experienced by the United States in the entire post-World War II era. The unemployment rate skyrocketed as high as 9.6 %, tied with 1982 and 1983 as the highest unemployment rates since the end of the Second World War. Yet the unemployment rate only provides part of the story of the United States’ weak labor market. This chapter goes well beyond the official unemployment statistics to look at the total pool of underutilized labor, including those who are working part time but cannot obtain full-time work (the underemployed) and those who have stopped looking for a job but want to be in the full-time work force (the hidden unemployed). It also rigorously examines the full array of labor market problems among U.S. workers in various education and income groups in 2013–2014 as well as providing relevant comparisons dating back to 1999–2000. We find that widening labor market outcome gaps have contributed to the growth of earnings and income disparities over the decade and a half since 1999–2000. Groups at the top end of the educational and income scales have come to experience virtually full employment and high earnings, while those at the bottom are dealing with unemployment and poverty that have sunk to levels last seen during the Great Depression.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Unemployment

- Underemployment

- Hidden unemployment

- Underutilized labor

- Labor market

- Educational attainment

- Household income

- Inequality

Introduction

Even with an unemployment rate that stood only a little above 5 % in early 2015, in reality, the labor markets of the nation began performing poorly starting with the arrival of the 2000s and have yet to fully recover. The first 10 years of the 2000s decade hit the nation’s workers particularly hard, with some economists and other social science analysts referring to 2000–2010 as the “Lost Decade.” (Chinn and Frieden 2011). After achieving full employment in its labor markets in 2000, the nation experienced a recession in early 2001 that lasted 8 months. It was followed by a largely jobless recovery marked by rising unemployment and other labor market problems that lasted close to 2 years (NBER 2015). Four years of job growth were then followed by the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and a slow jobs recovery that sharply increased the national unemployment rate and other labor underutilization problems through 2010.

It was the worst decade of job-creating performance experienced by the United States in the entire post-World War II era. The aggregate number of payroll wage and salary jobs over the decade fell by approximately 1.9 million, a stark contrast to the gains of 22.4 million jobs in the 1990s and nearly 19 million in the 1980s. After beginning the 2000s with an unemployment rate of only 4.0 % in 2000, the lowest since 1969, it skyrocketed to 9.6 %, which was tied with 1982 and 1983 as the highest unemployment rates since the end of the Second World War.Footnote 1 Yet the reason we say that the recovery has been weak is that the unemployment rate only provides part of the story. A serious understanding requires going well beyond the official unemployment statistics to look at the total pool of underutilized labor , including those who are working part time but cannot obtain full-time work (the underemployed ) and those who have stopped looking for a job but want to be in the full-time work force (the hidden unemployed ).Footnote 2 It also requires going beyond just the averages to include a careful examination of labor market problems as distributed by educational attainment and household income .Footnote 3

This report is devoted to performing such an analysis, rigorously examining the full array of labor market problems among U.S. workers in various education and income groups in 2013–2014 as well as providing relevant comparisons dating back to 1999–2000. The findings will examine the extent to which the combined underutilization problems among the nation’s workers have increased in recent years and the distribution of such labor market problems across key socioeconomic classifications of workers as represented by their educational attainment and household income groups.

This report also studies how many Americans fared in the labor market, including those with incomes below the official poverty threshold, as well as taking a broader look at those struggling economically—examining statistics on income inadequacy for the “near poor ” (those between 100 and 125 % of the poverty line) and those considered low income (those earning a maximum of double the official poverty line).

These widening labor market outcome gaps have contributed to the growth of earnings and income disparities over the decade and a half since 1999–2000. Groups at the top end of the educational and income scales have come to experience virtually full employment and high earnings, while those at the bottom are dealing with unemployment and poverty that have sunk to levels not seen since the Great Depression.

Defining Labor Underutilization

First, let us define the labor underutilization categories that we will examine regarding U.S. workers. Our estimates of these labor underutilization problems among workers in recent years (2013–2014) are based on findings of the Current Population Survey (CPS) of American households (Fig. 7.1). The CPS is sponsored jointly by the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and is the primary source of national labor force statistics.

The unemployed are those who did not work for pay or profit in the reference week of the survey but had actively looked for a job in the past 4 weeks and could have taken one if offered. Those persons who were not classified as employed or unemployed are placed into the “not in labor force” category.

The estimates of the numbers of the employed and unemployed are combined to form an estimate of the civilian labor force (Fig. 7.1). By dividing the number of unemployed persons by the civilian labor force, an estimate of the unemployment rate can be obtained. The unemployment rate is the most widely cited measure of labor underutilization in the national and local media, but it covers only a fraction of the labor market problems encountered by workers, especially less educated and low-income workers.

A second labor market problem is that of underemployment. An underemployed person is one who worked part time (under 35 h in the reference week) but desired and was available for full-time work.Footnote 4 Nationally, the numbers of underemployed increased sharply during the Great Recession and remained high (7–8 million persons per month) in the early years of the recovery. On average, the underemployed typically work only 21–22 h per week, barely half the mean number of weekly hours worked by the full-time employed. They receive less per hour in wages and thus less than half the mean weekly earnings of the full-time employed. There is a more than a short-time cost to being underemployed. Recent national research evidence has shown that working part time has no statistically significant effect on increasing one’s hourly earnings over the long term, which means being underemployed not only leads to earnings losses in the short run but perpetuates them for years to come.Footnote 5

A third measure of labor underutilization is the so-called “hidden unemployed,” or the labor force reserve . This is a fairly sizable group of individuals within the “not in labor force” population. Individuals in this group have not actively looked for a job in the past 4 weeks but expressed a desire for immediate employment at the time of the CPS. Their absence from the labor force reduces their current earnings and future incomes from work.

A subset of this group of the hidden unemployed is referred to by the Bureau of Labor Statistics as the marginally attached . These individuals must have looked for a job at some time in the past 52 weeks and been available to take a job in the reference week. Their numbers are typically only 40 % as high as the total number of the hidden unemployed. But we are focused on measuring the entire pool of hidden unemployed, not just the marginally attached.Footnote 6

Finally, in this chapter, we develop a count of the total pool of underutilized workers in the nation (for a review of the BLS alternative measures of labor underutilization, see U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2008). The underutilized represents the sum of the official unemployed, the underemployed, and the hidden unemployed. We also estimate a labor underutilization rate. This underutilization rate is calculated by dividing the number of underutilized workers by the adjusted civilian labor force. The adjusted civilian labor force represents the sum of the civilian labor force and the numbers of hidden unemployed.

In this report, we will provide estimates of four labor underutilization measures (unemployment rate , underemployment rate , hidden unemployment rate , and labor underutilization rate ) for all workers 16 and over.

Defining the Educational Attainment and Household Income Groups

The report is organized primarily around presenting these numbers in relation to the following:

-

Educational attainment groups: Workers are assigned to one of six educational attainment groups, ranging from those with no high school diploma or GED to those with a master’s or higher degree, including a professional degree (law, medicine, etc.)

-

No high school diploma or GED certificate

-

High school diploma or GED, no college

-

13–15 years of schooling, no college degree (some college)

-

Associate’s degree

-

Bachelor’s degree

-

Master’s or higher degree

-

-

Household income groups: Workers are categorized into six household income groups, ranging from a low of $20,000 in annual income to a high above $150,000

-

Under $20,000

-

$20,000 to $40,000

-

$40,000 to $75,000

-

$75,000 to $100,000

-

$100,000 to $150,000

-

$150,000 and over

-

-

Combinations of educational attainment/household income group

Disparities in the incidence of each of the four labor market problems across these groups will be presented and highlighted. The size of these disparities in labor market outcomes in 2013–2014 across socioeconomic groups will be shown to be far higher than those prevailing in 1999–2000, at the end of the labor market boom years of the 1990s. First, we will look at the unemployment rate.

Identifying Labor Underutilization Problems across Education and Household Income Groups in the U.S.

Unemployment Problems Among Workers Across Education and Income Groups in 2013–2014

The average unemployment rate of U.S. workers between January 2013 and December 2014 was 6.8 %.Footnote 7 But there is much more to the story. Around that average rate of unemployment stands a significant degree of inequality . Findings in Figs. 7.2, 7.3, and 7.4 show these socioeconomic disparities in unemployment rates in 2013–2014.

By Educational Attainment Group

When looking at educational attainment groups, unemployment rates varied quite widely. The unemployment rate was highest by far for those workers who did not have a high school diploma or GED , decreasing steadily with increased years in school (see Fig. 7.2). Workers that were high school dropouts or without a GED fared the worst with an unemployment rate of 13.9 %. The rate fell to 8.4 % for those that were high school graduates or held a GED, continuing downward to 4.1 % for those with a bachelor’s degree and a low of 2.9 % for those with a master’s degree or higher . The least educated workers were almost five times more likely to be unemployed than those with the highest levels of formal educational attainment.

To illustrate the degree to which workers in different educational groups were affected by the rise in unemployment rates, we compared their unemployment rates in 2013–2014 with those in 1999–2000 (see Table 7.1). Unemployment rates rose for members of each of the six educational groups; however, the absolute size of these increases was higher the less education one had completed. High school dropouts and graduates with no college experienced unemployment rate increase of about 4 percentage points, while workers with a bachelor’s or higher degree saw unemployment rates rise by 2 percentage points or less. The unemployment rate gap between high school graduates and bachelor’s degree holders widened from only 2.3 percentage points in 1999–2000 to 4.3 percentage points in 2013–2014.

By Household Income Group

Unemployment rates of workers also varied quite considerably across household income groups.Footnote 8 Unemployment rates were highest among lower-income workers and fell steadily and steeply as household income increased (see Fig. 7.3). Workers in the lowest household income group (under $20,000) had an unemployment rate of 19.2 %, with the rate falling to under 9.2 % for those with household incomes of $20,000–40,000. Workers in households with low-middle to middle incomes ($40,000–75,000) had unemployment rates of 5–6 %, with the rate under 3 % for workers in the most affluent households (those with annual incomes of $150,000 or more). Workers in the lowest income group were seven times more likely to be unemployed than those in the most affluent households in 2013–2014.

By Separate Educational Attainment/Household Income Groups

To identify the link between unemployment rates, educational attainment and household income, workers were combined into 36 separate educational attainment and household income groups, with unemployment rates calculated for each. The groups ranged from high school dropouts in households with low incomes ($20,000 per year) to workers with a master’s or higher degree that were in the most affluent households ($150,000 or more per year). The range in unemployment rate proved extraordinarily broad. The unemployment rates for these workers ranged from a high of 22.6 % for workers from low-income households and no high school diploma, to 9.4 % for high school graduates with below average incomes ($20,000–$40,000,) to a low of only 1.4 % for workers in the most affluent households ($150,000 and over) that held a master’s or higher degree. Workers from the lowest income households who did not have a high school diploma were 16 times more likely to be unemployed than the best educated workers from the most affluent households (see Fig. 7.4). Well-educated Americans from high-income families lived in a super full employment labor market, while less educated, low-income workers were facing Depression-level unemployment rates.

Underemployment Problems Among U.S. Workers

Underemployment problems of U.S. workers rose substantially during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and its early aftermath, setting new record highs (Sum and Khatiwada 2010, pp. 3–10). In 1999–2000, there was an average of only 3.3 million persons per month who worked part time but desired full-time work. By 2013–2014, this number had risen by more than 130 % to 7.6 million.Footnote 9

By Educational Attainment Group

Underemployment rates of workers were strongly associated with individuals’ educational attainment ; with the rates being the highest for the least educated workers and falling progressively for those with more education (see Fig. 7.5). The underemployment rate for workers without a high school diploma or GED was 9.9 %, falling to 6.8 % for those with a diploma or GED. Rates dropped to 3.1 % for those with a bachelor’s degree and only 2.0 % for those with a master’s or higher degree . The least educated workers were five times more likely to experience underemployment problems than the best educated workers during 2013–2014.

By Household Income Group

The incidence of underemployment among workers also varied considerably by the level of household income. Underemployment rates were highest for workers in the least affluent households, with rates decreasing steeply as annual household income grew (see Fig. 7.6). Workers in the least affluent households (earning less than $20,000 per year) had an underemployment rate of 14.2 %, with the rate falling sharply to 7.7 % and 3.9 % for low-middle and middle-income workers and dropping to 2.6 % for workers in families earning $100,000–$150,000 per year. The most affluent workers (income above $150,000) had an underemployment rate of just 2 %. Low-income workers were seven times more likely to be underemployed than the most affluent workers.

By Separate Educational Attainment/Household Income Groups

The underemployment rates of workers in 2013–2014 varied sharply and systematically across the various educational attainment/household income groups (see Fig. 7.7). The lowest income workers who had not completed high school had an underemployment rate of 17.7 %. The underemployment rate fell sharply to 7.8 % for low-income workers who were high school graduates and reached a low of only 1 % for the highest income workers with a master’s or higher degree. The least educated and lowest income workers were 17 times more like to be underemployed than the most affluent workers who held graduate and professional degrees.

The overall level and incidence of underemployment problems increased substantially between 1999–2000 and 2013–2014 (see Table 7.2). In 1999–2000, the underemployment rate was only 2.4 % but rose sharply to 5.2 % in 2013–2014. In both time periods, underemployment problems were strongly linked to combinations of unemployment and household income. In each of these groups, the underemployment rate rose over this time period; however, the size of these percentage-point increases varied quite widely across those groups. At the bottom, the underemployment rates of low income without a high school diploma/GED increased by nearly 9 percentage points from 8.8 to 17.7 % between 1999–2000 and 2013–2014; among low-income-high school graduates, the underemployment rate doubled from 4.3 to 9.9 % over the same time period. At the top of the education ladder (bachelor’s degree and above) with incomes over $75,000, the underemployment rates rose by only 1.4 percentage points or less. The size of the percentage point increase in underemployment among low-income high school dropouts and graduates was 4–12 times as high as that at the top. Underemployment rates have become massively more unequal over time. The steep weekly wage losses from being underemployed took a severe toll at the bottom of the wage distribution, creating more wage inequality over time.

The Problems of Hidden Unemployment Among Workers in 2013–2014

A third set of labor market problems facing workers is that of the hidden unemployed, or members of the so-called labor force reserve (for a discussion of this concept, see Ginzberg 1978). The number of persons in the labor force reserve and the marginally attached tend to rise sharply during recessions and jobless recoveries .Footnote 10 Although they do not count toward official unemployed figures, their joblessness contributes to personal wage losses and output losses just as if they were unemployed. Their more limited work experience resulting from these periods of hidden unemployment will also have negative effects on future employability and earnings.

Hidden Unemployment Rates Among Workers

By Educational Attainment Group

Hidden unemployment rates were strongly associated with the educational attainment of workers in 2013–2014 (see Fig. 7.8). The incidence of hidden unemployment was highest for workers with no high school diploma or GED, with the likelihood of being part of the hidden unemployed decreasing as the level of educational attainment increased (see Fig. 7.8). Workers who were the least educated (those with no high school diploma or GED) had a hidden unemployment rate of just under 9 %, with rates dropping to 4 % for those who had graduated from high school or completed some college but were without a degree.Footnote 11 Those workers with a bachelor’s or higher degree had a 2 % or lower rate of incidence of hidden unemployment. Workers with the lowest educational attainment were four and five times more likely to suffer hidden unemployment problems than the best educated.

By Household Income Group

The likelihood of being a member of the hidden unemployed in 2013–2014 also was strongly linked to the household incomes of potential workers. As with the unemployed and underemployed, the lowest income individuals in the adjusted labor force were the most likely to be members of the hidden labor force. Nearly one in every ten individuals with household incomes below $20,000 was in the ranks of the hidden unemployed (see Fig. 7.9). The probability of hidden unemployment continued to decline as household income grew, dropping to 3 % for middle-income workers and under 2 % for those with household incomes over $100,000. Workers in the lowest income groups were between five and six times more likely to suffer a hidden unemployment problem than the nation’s most affluent workers in the 2013–2014 time period.

By Separate Educational Attainment/Household Income Groups

The rates of hidden unemployment among workers in 2013–2014 varied considerably across the 36 different educational attainment/household income groups. Hidden unemployment problems were most prevalent among high school dropouts in the lowest income group, who had a hidden unemployment rate just under 13 %, which dropped to 4.4 % for lower-middle income high school graduates (see Fig. 7.10). The most affluent, best educated workers had a hidden unemployment rate under 1 %. Workers with the lowest educational attainment living in the lowest income households were 15 times more likely to suffer a hidden unemployment problem than the most affluent and most highly educated workers in 2013–2014. Hidden unemployment was virtually an unknown phenomenon among the most affluent and educated.

Labor Underutilization Problems in the U.S. in 2013–2014

The three labor market problems of unemployment, underemployment, and hidden unemployment can now be combined to form a pool of “underutilized labor .”Footnote 12 The estimated average monthly number of unemployed in 2013–2014 was 10.6 million (see Fig. 7.11). That number, however, was exceeded by the combined total of underemployed and hidden unemployed (7.6 million underemployed and 5.8 million hidden unemployed, or 13.4 million altogether). The joint pool of underutilized labor was equal to 24.1 million, or 14.9 % of the adjusted resident labor force of the nation in 2013–2014.Footnote 13 Thus, approximately one of every six members of the resident labor force experienced some type of labor underutilization problem.

Labor Underutilization Rates Among Workers

By Educational Attainment Group

The rates of labor force underutilization among workers in 2013–2014 varied widely by educational attainment. Given our previous findings on each individual labor market problem, it should come as no surprise to discover that the highest rate of underutilization was found among the least educated workers and declined as educational attainment increased (see Fig. 7.12). Those workers who did not possess either a high school diploma or GED had an underutilization rate of 29.4 %, which dropped to 18.1 % for those with a high school diploma. Four-year college graduates had an underutilization rate of just under 9 %, while those workers holding a master’s or higher degree had only a rate of 6.5 %. The least educated workers were between three and four times more likely to be part of the underutilized labor force than the best educated workers in the 2013–2014 time period.

Comparisons of the labor underutilization rates of workers by educational attainment in 1999–2000 with those for 2013–2014 are presented in Table 7.3. These underutilization rates increased over time in every educational group, but the percentage point sizes of these increases were substantially greater at the bottom of the education distribution than at the top. The size of these increases was highest among those lacking a high school diploma/GED (9 %), stayed at 8 % for high school graduates and those with some college but no degree, and rose by only 4.4 and three percentage points for bachelor’s degree holders and those with a master’s or higher degree, respectively. In 1999–2000, there was only a five-point gap between the underutilization rates of high school graduates and those workers with a bachelor’s degree. By 2013–2014, this gap had widened to nine points.

By Household Income Group

Labor force underutilization problems among workers during the 2013–2014 time period also were strongly associated with household income. The rate of labor force underutilization was greatest for low-income workers (under $20,000), with rates falling sharply and steadily as household income grew (see Fig. 7.13). The labor underutilization rate for workers in households with an annual income below $20,000 was 37 %, with the rate falling to 20 % and 13 % for low-middle and middle-income workers and finally dropping to 6 % for members of the highest income households ($150,000 or more per year). Workers in low-income households were roughly six times more likely than the most affluent to experience a labor underutilization problem in 2013–2014. Their labor market problems are clearly massively different from one another, with a gap of 31 percentage points.

By Separate Educational Attainment/Household Income Groups

Labor underutilization rates also were calculated for 36 educational attainment/household income groups. There was tremendous variability in these rates across these 36 separate groups of workers. Underutilization problems were most severe by far for the lowest income and least educated workers, easing as both household income and educational attainment increased (see Fig. 7.14). Workers without a high school diploma or a GED and from families with incomes under $20,000 had an underutilization rate of nearly 44 %. This rate fell to 20 % for low-middle-income, high school graduates and to 13 % for those with some college and in a middle-income household, dropping to only 3 % for workers that held a master’s or higher degree in a household with annual earnings of $150,000 or more. The least educated and lowest income workers were nearly 14 times more likely to suffer labor underutilization problems than the most affluent and best educated workers were in 2013–2014.

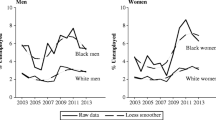

We also identified the degree to which these patterns of labor force underutilization across educational attainment and household income groups may have varied across gender and race-ethnic group , estimating such rates for both men and women and for Blacks, Hispanics, and White non-Hispanics separately (see Table 7.4). The overall underutilization rates of men and women followed similar patterns to the overall numbers.

But across the three major race-ethnic groups, the overall labor underutilization rates varied widely from a low of under 12 % for White non-Hispanics to 19 % for Hispanics to 23 % for Blacks. The patterns of these findings across educational attainment and household income groups are quite similar. All three groups experienced substantial drops in labor underutilization rates as their household income and educational attainment improved. In Fig. 7.15, we present findings for two groups at both extreme portions of the distribution for each race-ethnic group. Hispanic and Black low-income high school dropouts faced underutilization rates of 37 % and nearly 60 %, respectively.Footnote 14 In contrast, those with a master’s or higher degree in the highest income group had underutilization rates of only 3–4 % for each race-ethnic group. The large disparities in labor underutilization rates across socioeconomic groups are, thus, common to both men and women as well as across Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites, with Blacks facing the highest underutilization rates overall. (Appendix 7A contains a number of tables regarding labor underutilization rates by gender and race-ethnic groups, illustrating the depth of family income inadequacy problems. For detail about associations between educational attainment/household income groups by gender and race-ethnicity, see Appendix 7B).

The Findings of Logistic Probability Models to Predict Labor Underutilization among Workers in 2013–2014

The above findings on the labor market problems of adults have primarily focused on variations in these problems across educational attainment and family income groups with a few separate breakouts of key findings for gender and race-ethnic groups. To illustrate the independent effects of other demographic variables on the underutilization rates of workers in 2013–2014, we have estimated a set of logistic probability models of their underutilization status over this 2-year period (for a description of this process and full detail about the logistic probability regression model, see Appendix 7C, including Table 7C.2).

The findings of the logistic probability regression model of the underutilized status of workers in 2013–2014 can be used to predict the probability of a given labor force participant with specific demographic and socioeconomic traits being underutilized at the time of the CPS household surveys in 2013–2014. The predicted probabilities of being underutilized in the labor market of six male individuals with very different demographic and socioeconomic backgrounds are presented in Table 7.5 (the specific formula used to generate these probability estimates is explained in Appendix 7D).Footnote 15

The first individual was a young (16- to 24-year-old) Black, native born male who was a high school dropout and lived in a low-income household (annual income under $20,000). His predicted probability of being underutilized in the labor market was an extraordinarily high 66.7 %. If this individual had been White and had a high school diploma and lived in a low-income family, his predicted probability of being underutilized was also quite high at 45.5 %. As the age of the respondent and family income increased, the predicted probability of being underutilized declined. A 25- to 34-year-old White, male high school graduate from a low-middle-income family ($20,000–$40,000) had a 14 % probability of being underutilized.

If the respondent’s age rose to 35–44, his education increased to 13–15 years with no formal degree, and his family income increased to the $40,000–75,000 range, then his probability of being underutilized declined to 8.2 %. A native born 55- to 64-year-old male with a bachelor’s or higher degree who lived in an affluent family ($150,000 or higher) had only a 4.5 % probability of being underutilized.

The findings of the above analyses are quite clear. Young, poorly educated adults from low-income families faced underutilization rates of historic proportions. They encountered Depression-era unemployment and other labor market problems in 2013–2014. Even young high school graduates from low-middle-income families faced high rates of labor underutilization. In contrast, older males (45–64) with a bachelor’s or higher degree and above average incomes experienced very low labor underutilization rates that would have to be considered the equivalent of super full employment in the labor market. America’s labor markets have become extremely stratified by age, education, and family income since 2000. Gaps in labor underutilization rates between the top and bottom of the distribution exceeded 60 percentage points, representing more than 15 times difference in relative terms.

The Labor Underutilization Problems of the Nation’s Young Adults (16–29) in 2013–2014

Since the end of the nation’s labor market boom years of the 1990s, national labor markets have been characterized by a “great age twist” in the structure of employment rates.Footnote 16 While the nation’s older adults (57 and older) had higher employment rates in 2010–2011 than they did in 1999–2000, all younger adults had lower employment rates. These declines were sharpest with the youngest age groups. As was the case in many other OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries, U.S. teens fared the worst in the labor market by far, followed by 20–24 year olds, and 25–29 year olds (Sum et al. 2014a).

The annual average employment rates of the nation’s teens (16–19 years old) fell from 45 % in 1999–2000 to only 28 % in 2013–2014 (see Fig. 7.16).Footnote 17 Steep declines in employment rates were experienced by the nation’s teens in every age, gender, race-ethnicity, and family income group, but employment rates remained lowest among the youngest teens (16–17), Blacks and Hispanics, high school students and dropouts, and low-income youth.

The employment/population ratio (E/P) of the nation’s young adults (20–24) fell by 10 percentage points over the same time period, creating a new historical low for young U.S. adult men, while the ratio for 25–29 year olds dropped from 81 to 74 %, a seven percentage point decline. The deteriorating employment prospects for teens have had negative impacts on their employability as young adults here and in most other OECD nations. They have seen reduced ability to form independent households, leading more to remain living at home with one or both parents (for estimates of earnings losses among young unemployed workers, see Ayres 2013). These same factors also have led to a reduction in marriage rates among the young, which has helped raise the share of new births taking place out of wedlock to all-time highs.Footnote 18 With that said, part of the decline in employment for young people can be attributed to more young people being enrolled in colleges/schools. But the largest decline occurred among teens who were not enrolled (Table 7.6).

These income and family formation developments have contributed in an important way to declining real incomes of young families with children and to higher rates of poverty among them. Young families’ incomes (a family head under 30 years of age) have been subject to widening inequality over the past few decades, with the top decile (one-tenth) of families’ gains equaling close to half of all young family incomes (McLaughlin et al. 2010). Wealth gaps among young households have increased to an even greater degree, with the top 10 % capturing 86 % of the net worth of young households in 2007 (Sum and Khatiwada 2009).

Given the high and rising degrees of labor underutilization among the nation’s teens and young adults, we also estimated a logistic probability model of labor underutilization among those labor force participants under age 30 in 2013–2014. For full detail, see Appendix 7E.

We have picked five young males (from ages 16–19 to 25–29) with different race-ethnicity, educational attainment, and family income backgrounds and used the logistic probability model to estimate their predicted probability of being underutilized in 2013–2014 (see Table 7.7).

Our first individual is a teenaged Black male, who was a high school dropout and lived in a low-income family. His predicted probability of being underutilized was an astonishingly high 73 %. If we made this young man a White male and raised his age to 20–24 but kept his education and family income status unchanged, his estimated probability of being underutilized still remained at 47 %. If this same young man’s educational attainment was raised to that of a high school graduate and his family income raised to $20,000–$40,000, then his probability of being underutilized fell to 26.8 %.

If his educational attainment was increased to that of an associate’s degree and his family income increased to a middle-income level, his probability of being underutilized dropped to 14.2 %. Our final individual is a 25- to 29-year-old White non-Hispanic male who was native born, had a bachelor’s or higher degree, and lived in an upper middle-income family ($75,000–100,000). His predicted probability of being underutilized was only 6.8 %, or basically only one-eleventh as high as that of our first individual (the Black, male, teen dropout from a low-income family). The distribution of labor underutilization rates among our nation’s young adults in 2013–2014 was extraordinarily varied, with potentially severe adverse consequences for future family formation, income and earnings inequality, and the economic and social well-being of children in these families.

Trends in Labor Underutilization Rates Among Adults (16 and Over) by Educational Attainment and Household Income, 1999–2000 to 2013–2014

In our prior analyses of the labor underutilization rates of the nation’s working-age population, we tracked variations in these rates across educational attainment and household income groups in 2013–2014. In this section of our chapter, we compare key findings from the 2013–2014 surveys with those for 1999–2000, when the national economy was operating under full employment conditions in its labor markets (see Table 7.8).

In 1999–2000, the overall labor underutilization rate was 9.1 %, varying from a high of about 30 % among low-income dropouts to only under 3 % for bachelor’s and higher degree holders with household incomes above $75,000.

By 2013–2014, the aggregate labor underutilization rate had increased to 14.9 %. Each demographic, educational attainment, and household income group of labor force participants encountered an increase in its labor underutilization rates, but the percentage point sizes of these increases varied quite widely across these groups (see Fig. 7.17). Low-income workers with a high school diploma or less in formal schooling saw their labor underutilization rates rise by 14–16 percentage points. At the lower end of the distribution of underutilization rates were bachelor’s or higher degree recipients from upper-income families. Their underutilization rates rose by only to two to three percentage points over this 14-year period. Adults with a master’s or higher degree and a family income greater than $75,000 faced a labor underutilization rate of only 4 % in 2013–2014, two percentage points higher than in 1999–2000.

America’s adults clearly faced a deep set of widening gaps in their labor underutilization rates since 1999–2000. At the top of the distribution are low-income adults with only a high school diploma or less education with underutilization rates of 38–44 %—a Depression-era labor market environment. High school graduates from low-middle-income families faced a 20 % labor underutilization rate, equivalent to several points above the worst during the Great Recession of 2007–2009. At the bottom of the distribution are college graduates (bachelor’s and above) with affluent family incomes who live in a world characterized by super full employment. These are radically different labor market worlds.

Income Problems of Underutilized Workers, 2012–2013

The previous sections of this chapter have been focused on the labor underutilization problems of workers in an array of educational attainment and household income groups, also looking at gender, age, and race-ethnic groups. This section of the chapter now assesses another set of issues related to the impact on income of underutilized workers.

A labor underutilization problem by itself does not have to automatically lead to poverty or low-income status. For example, an unemployed worker may experience only a short duration of unemployment (2–4 weeks) that does not have a major impact on annual income. The unemployed worker may be a young household member who does not contribute to household income in a substantive way, or the unemployed or underemployed persons may be a secondary earner whose temporary loss of income does not reduce the household’s income below the poverty line or low-income standard.

But labor underutilization problems following the 2007–2009 recession were accompanied by steep increases in the mean durations of unemployment, with long-term unemployment problems (26 weeks or more) increasing in share to over 37 % in 2014.Footnote 19 These long-term unemployment spells create higher mean annual earnings losses despite the existence of unemployment benefits. The steep rise in underemployment with its high weekly wage losses also sharply reduces the earnings of this group, placing individuals at risk of income inadequacy.

We will begin our analysis of the links between labor underutilization problems and income inadequacy problems with a brief overview of the three measures of income inadequacy and their values for selected families and individuals in 2012–2013. This will be followed by an examination of the links between labor underutilization and incidence of income inadequacy problems both overall and for workers in each major educational attainment subgroup (for a review of the official poverty measures of the federal government and alternative measures of poverty, see U.S. Census Bureau 2010). We will also provide separate breakouts of these income inadequacy problems by combinations of educational attainment and labor underutilization status, showing the degree to which U.S. labor markets today are affected.

The Three Income Inadequacy Measures

Three separate measures of income inadequacy are used in this report, which are the poverty income thresholds of the federal government: those who are poor, near poor, or low income. These are defined as follows:

-

Poor: Annual money income, pretax, below the official poverty line for persons or families by family size and age composition.

-

Poor or near poor: Annual money income below 125 % of the official poverty line.

-

Low income: Annual money income below 200 % of the official poverty line.Footnote 20

For 2013, the values of the income thresholds defining each of these measures for a single individual and three types of families are displayed in Table 7.9. The poverty income thresholds ranged from $12,119 for a single nonelderly individual to $23,624 for a four-person family with two children under 18. By definition, the values of the low-income thresholds were twice the value of the poverty line, ranging from $24,238 to $47,248 in our examples.

The Poverty Rates of Workers by Underutilization Status and Educational Attainment

The poverty rates of workers (including the hidden unemployed) by labor force underutilization status in March 2013–2014 are displayed in Table 7.10.Footnote 21 Findings are presented for all workers and for men and women separately by educational attainment for our six educational groups.

Overall, slightly over 9 % of all workers were members of poor families in March 2013–2014. The underutilized, however, were nearly 4.7 times as likely to be poor as their counterparts who were not underutilized (27.1 % vs. less than 5.8 %) (see Fig. 7.18). Clearly, being underutilized substantially increases the probability of poverty among workers. Among the underutilized, the likelihood of being poor also was associated with educational attainment Slightly more than 38 % of the underutilized without a high school diploma or GED were poor (Fig. 7.19). The poverty rate fell to 29 % for those with a high school diploma, and to only approximately 15 % for those with a bachelor’s or higher degree.

Data on the underutilization status of workers was combined with findings on their educational attainment to produce estimates of these joint factors on the probability of being poor (see Fig. 7.20). Of those underutilized workers with no high school diploma, 38 % were poor. This poverty rate declined to 29 % for those underutilized workers with a high school diploma. Of those workers not underutilized, the poverty rate fell to only 2.5 % for those with a bachelor’s degree and to only 1.5 % for those with a master’s or higher degree. America’s best educated workers who were not underutilized faced close to a zero rate of poverty, while the less educated, underutilized individuals faced extremely high rates of poverty in the 30–40 % range.

Poverty/Near Poverty Problems of the Underutilized

Our second measure of income inadequacy focuses on those persons with annual family incomes below 125 % of the poverty line: the poor and near poor. Overall, from March 2013 to March 2014, approximately one of every eight workers (12.5 %) was a member of a poor or near-poor family (see Table 7.11 and Fig. 7.21). Among the underutilized, however, one-third were poor or near poor versus only 8.6 % of the not underutilized, a relative difference of nearly four times.

Among the underutilized, the poverty/near poverty rates of workers varied across educational attainment groups, being highest for those with the least education and falling with the level of educational attainment (see Fig. 7.22). Those underutilized workers lacking a high school diploma or GED faced a poverty/near poverty rate of 47 %. This rate declined to 30 % for those with 1–3 years of college, and to a low of 16 % for those with a master’s or higher degree. The least well educated underutilized workers were about 2.3 times as likely to be poor or near poor as their counterparts with a four-year or higher college degree.

The findings on the underutilization status of workers were combined with their educational attainment to estimate poverty/near poverty rates for various subgroups of such workers. The poverty/near poverty rates of these workers ranged quite widely across these various subgroups (see Fig. 7.23). Close to 50 % of underutilized, high school dropouts were poor/near poor versus slightly more than one-third of high school graduates. Among those workers who were not underutilized, just 11 % of high school graduates were members of poor/near poor families and under 3 % of those with a bachelor’s or higher degree. Poverty/near poverty rates of underutilized high school dropouts were 17 times greater than those of the college educated who were not underutilized.

Low-Income Problems of Workers by Labor Underutilization and Educational Attainment

Our final measure of the income inadequacy problems of workers is that of their low-income status; that is, a family income that is twice the poverty line or less. Approximately one in four workers was living in low-income families in March 2013–2014 (see Fig. 7.24). Among those with an underutilization problem, one-half (51 %) had household income below our low-income threshold. In comparison, among those who were not underutilized, the incidence of such low-income problems was only 19 %, or less than two-fifths that of the underutilized.

Again, the incidence of income inadequacy problems among underutilized workers varied across educational groups, being highest for the less educated and falling with additional levels of educational attainment. Two-thirds of the underutilized who lacked a high school diploma or GED were low income versus 55.6 % of high school graduates and 33 % of those with a bachelor’s degree (see Fig. 7.25). Clearly, even among the well educated, labor underutilization creates severe low-income problems, though they fare far better than their less educated peers.

In the final set of analysis, we generated estimates of low-income problems among various groups of workers categorized by their educational attainment and labor underutilization status. Both factors together have a massive impact on the likelihood of being low income in 2013–2014. At the upper end of the distribution of low-income rates are high school dropouts who were underutilized in the labor market. Two-thirds of these individuals were low income. Even among high school graduates, a majority (55.6 %) of the underutilized had household income below the low-income threshold (see Fig. 7.26).

Among those who were not underutilized, the incidence of low-income problems was only 8.8 % for those with a bachelor’s degree and only 4.7 % for those with a master’s or higher degree (see Table 7.12). The least well-educated members of the underutilized were 14 times as likely to be low income as the best educated members of those workers who were not underutilized in the labor market. Clearly, the division of American workers into a low-income/not-low-income status is substantially influenced by formal schooling and labor underutilization status. Being underutilized by itself was also found to be significantly influenced by educational attainment.

Conclusion

From 2000 to 2014, the labor market problems of U.S. workers were characterized by a massive degree of inequality across socioeconomic strata. The nation’s labor market problems were very unevenly distributed across workers based on differences in household incomes and educational attainment. In comparison to college-educated and affluent workers, younger, race-ethnic minority, less educated, lower-income workers faced extraordinarily high rates of labor underutilization in the form of unemployment, underemployment, and hidden unemployment. We found that on every labor market outcome measure, the gap between affluent, college-educated and low-income, less-educated groups have widened. Both during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 as well as the subsequent weak GDP and jobs recovery through 2014, workers at the lower end of the socioeconomic ladder have faced labor market problems similar to that of the Great Depression era, while those at the higher end of the socioeconomic ladder experienced near full employment labor market conditions. Unsurprisingly, we found that the income inadequacy status of U.S. workers was heavily influenced by their formal schooling and labor force underutilization status.

These findings make it abundantly clear that labor market problems across educational groups interact substantially with household income. Being less educated and low income places one at a sharply higher risk of labor market underutilization, while for America’s best educated and affluent workers, the problem isn’t nonexistent, but nearly so. These findings make it quite clear that it is difficult to talk about the “average” unemployment rate or the “average” labor underutilization rate in such labor markets. As economic analysts often agree, “the average is over” (Cohen 2013).

Limitations of the U.S. labor market in recent years have taken a tangible toll on the nation's less educated and low-income workers; contributing to growing earnings and wage inequality and family income inequality, and to poverty and other problems associated with low incomes. A full employment economy similar to that of the 1994–2000 period helped raise weekly wages, annual earnings, and family incomes, bringing rising family income inequality at least temporarily to a halt, and reduced poverty problems, including among children. Restoring economic opportunity in the United States cannot take place without a much more favorable labor market environment.

Notes

- 1.

For an overview of national unemployment rates from 1947 to 2000, see U.S. Council of Economic Advisers 2002.

- 2.

For a recent review of the labor market problems of young college graduates in obtaining jobs related to a college degree, see Katherine Peralta, “College Grads. Taking Many Low Wage Jobs,” Boston Globe, March 10, 2014.

- 3.

See Sum and Khatiwada 2012 for a more careful explanation of these labor underutilization measures.

- 4.

For an overview and assessment of the rising incidence of underemployment problems during the Great Recession, see Sum and Khatiwada 2010, pp. 3–13.

- 5.

- 6.

The labor force reserve or hidden unemployed is typically more than twice as large as the marginally attached labor force. For example, in July 2013, the number of persons in the labor force reserve was 6.86 million, while the marginally attached labor force was only 2.53 million.

- 7.

In 2009 and 2010, the unemployment rate of U.S. workers was 9.5 %.

- 8.

These statistics come from monthly Current Population Surveys, where respondents are asked to report total combined income received by the household members during the past 12 months. The incomes are reported in categorical form. The income includes wage and salary income, farm/nonfarm, self-employment incomes, Social Security/Supplemental Security Incomes, pensions/interests/dividends incomes, net rental income, cash public assistance income, unemployment or workers’ compensation incomes, pension or retirement incomes, and all other incomes.

- 9.

In 2009–2010, on average, 8.9 million persons per month were working part time but desired full-time work.

- 10.

The members of the marginally attached and discouraged workers tend to rise during recessions and jobless recoveries. See Cohany (2009).

- 11.

High school students not reported separately also had a very high hidden rate of unemployment. Close to 22 % of these individuals in the labor force were hidden unemployed in 2013–2014.

- 12.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics U-1 through U-6 framework for estimating labor problems includes a measure (U-6) that is somewhat similar to ours. It counts in the numerator the sum of the unemployed, the underemployed, and the marginally attached, which are a subset of the hidden unemployed. See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2008, 2014.

- 13.

In 2009–2010, representing the labor market trough of the Great Recession, 29.1 million persons were members of the labor force underutilized pool (14.7 million unemployed, 8.9 million underemployed, and 5.5 million hidden unemployed).

- 14.

The labor force underutilization rate among native-born Hispanics without a high school diploma or a GED was much higher than their foreign-born peers. In 2013–2014, the underutilization rate among native-born Hispanics was 36 % compared to 22 % among their foreign-born peers.

- 15.

The estimated impact of gender on the probability of being underutilized was quite small (<1 percentage point), thus, we have limited our analysis to males only though the results for women would be quite similar.

- 16.

For a detailed review and assessment of the changing labor market experiences of teens and young adults (20–24) in the U.S., see Sum et al. 2014b.

- 17.

See Josh Sanbum, “Fewest Young Adults (18–24) in 60 Years Have Jobs,” Business.com, February 9, 2012.

- 18.

Over 50 % of all births to women under 30 in 2011 were out of wedlock, the first time ever that a majority of such births took place outside of marriage.

- 19.

In 2010–2011, more than 47 % of the nation’s unemployed had been out of work for 26 weeks or longer.

- 20.

A number of poverty researchers and income analysts began using this definition of low income in the late 1990s. See Acs et al. (2000).

- 21.

Poverty status is based on the annual income received by the respondent’s family in the prior calendar year; i.e., 2012 or 2013.

- 22.

With the exception of members of the labor force reserve, all other nonparticipants in the civilian labor force are excluded from the analysis.

- 23.

The logistic coefficients on the independent variables were converted into estimated marginal probability effects. A standard practice in the literature is to calculate these marginal probability effects at the means of all right hand side variables. We can convert the logit regression coefficients (Bs) into a set of marginal effects by multiplying the value of each logistic coefficient (B) by (P) and (1-P), where P is the percent of workers in the sample who were underutilized in 2013–2014.

- 24.

The expected probability of labor underutilization among the base group was only 5.9 percentage points.

- 25.

Male teens and those 20–24 were heavily hit by changing employment developments over the 2000–2014 time period, including the high loss of blue-collar jobs that impacted young men more than young women.

References

Acs, Gregory, Katherin R. Phillips, and Daniel McKenzie. 2000. Playing the rules but losing the game: America’s working poor. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Ayres, Sara. 2013. The high cost of youth unemployment. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

Blau, Francine, and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2013. The feasibility and importance of adding measures of actual experience to cross-section data collection. Journal of Labor Economics 31(April): S17–S58.

Census Bureau, U.S. 2010. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2009. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Chinn, Menzie D., and Jeffrey Frieden. 2011. Lost decades. New York: W.W. Norton and Co.

Cohany, Sharon. 2009. Ranks of discouraged workers and other marginally attached to the labor force rise during recession, Issues in labor statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April.

Cohen, Tyler. 2013. Average is over: Powering America beyond the age of the great stagnation. New York: Penguin Group.

Ginzberg, Eli. 1978. Good jobs, bad jobs, and no jobs. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McLaughlin, Joseph, Andrew Sum, Ishwar Khatiwada, and Sheila Palma. 2010. Trends in the levels and distribution of young family incomes, 1979–2009. Washington, DC: Children’s Defense Fund.

NBER (National Bureau of Economic Research). 2015. U.S. business cycle expansions and contractions. www.nber.org/cycles.

Sum, Andrew, and Ishwar Khatiwada. 2009. The wealth of the nation’s young. Challenge (November/December): 96–100.

Sum, Andrew, and Ishwar Khatiwada. 2010. The nation’s underemployed in the great recession of 2007–2009. Monthly Labor Review (November): 3–13.

Sum, Andrew, and Ishwar Khatiwada. 2012. Endnotes: Going beyond the unemployment statistics: The case for multiple measures of labor underutilization. Mass Benchmarks 14(2): 19–24.

Sum, Andrew, Ishwar Khatiwada, and Walter McHugh. 2014a. Deteriorating labor market fortunes of teens: Consequences for future young adult employment in our nation, Challenge (May/June).

Sum, Andrew, Martha Ross, Ishwar Khatiwada, and Mykhaylo Trubskyy. 2014b. The changing labor market fortunes of teens (16–19) and young adults (20–24) years old in the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan areas during the lost decade. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, March.

Tienda, Marta, V. Joseph Hotz, Avner Ahituv, and Michelle Bellessa. 2010. Employment and wage prospects of Black, White, and Hispanic women. In Economics and public policy, ed. Human Resource, 129–160. Kalamazoo: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2008. The unemployment rate and beyond: Alternative measures of labor underutilization. Washington, DC, June.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2014. The employment situation: February 2014. Released March 8. Washington, DC.

U.S. Council of Economic Advisers. 2002. Economic report of the president, February. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendices

Appendix 7A: Labor Underutilization Rates by Gender and Race-Ethnic Groups

In the main part of the chapter, we analyzed variations in an array of labor market problems (unemployment, underemployment, hidden unemployment, and labor underutilization) across workers in various educational and household income groups in labor markets in 2013 and 2014. For gender and race-ethnic groups, we also presented selected findings for combinations of educational attainment and household income.

This appendix provides more detailed findings on the labor underutilization rates of workers in each gender and five race-ethnic groups (Asian, Black, Hispanic, Other, White, not Hispanic). For each of these seven groups as well as all workers, we provide estimates of labor underutilization rates in 2013–2014 for six educational attainment groups cross-tabulated by household income in seven income categories ranging from a low of under $20,000 (which we refer to as low income) to a high of $150,000 or more, which we refer to as the most affluent group of workers in the U.S.

Table 7A.1 provides the estimates of these labor underutilization rates for all workers (16 and over), including the hidden unemployed. As revealed in the main report, the labor underutilization rates of workers varied widely across educational attainment groups, ranging from a high of 29 % among those lacking a high school diploma, to 18 % for high school graduates with no college, to a low of just 6.5 % for those workers holding a master’s or higher degree (see Table 7A.1).

For each gender and race-ethnic group, we have compared the estimates of labor underutilization rates from those workers lacking a high school diploma and those with a master’s or higher degree (see Table 7A.2) and taken the ratio of these two estimates (see Column C). The labor underutilization rate of high school dropouts was 29 % versus slightly below 6 % for those with a master’s or higher degree. The relative difference in underutilization rates for these two groups of workers was between four and five times.

Very similar ratios prevailed among both men and women. Across the five race-ethnic groups, these relative differences in labor underutilization rates ranged from lows of 3.0–3.2 among Asian and Hispanic workers to highs of 5–6 among Black and other races, including Native American and those of mixed races. With the exception of Asians, where high school dropouts faced a labor underutilization rate of 21 %, dropouts in both gender and other four race-ethnic groups often experienced underutilization rates in the 25–46 % range. Such high underutilization rates sharply reduce their expected annual earnings, and when combined with low incomes of other family members, they often place such individuals at high risk of poverty and other income inadequacy problems.

The underutilization rates of workers in seven household income groups were calculated separately, both overall and for gender and race-ethnic groups. In Table 7A.3, we compare these labor underutilization rates for workers in low-income (under $20,000) and affluent households ($150,000 and over). Overall, 37.2 % of the workers from low-income households were underutilized versus only 6.2 % in affluent households, a relative difference of six times.

These large absolute and relative gaps in labor underutilization rates between affluent and low-income workers prevailed among both gender groups and each race-ethnic group in 2013–2014. Thirty-seven percent of both low-income male and female workers faced labor underutilization problems, five to six times as high as those encountered by affluent workers of both genders. Among the five race-ethnic groups, low-income workers faced underutilization rates of 32–46 % in four of these race-ethnic groups (the rate for Asians was 32 %), with relative differences typically in the four to six times range. Across the board, low-income workers in every demographic group clearly experienced labor underutilization rates well above those of the nation’s most affluent workers, contributing to rising earnings and family income inequality and to widening gaps in family income inadequacy problems.

The incidence of problems of labor underutilization across educational groups was strongly, positively correlated with household income differences in labor underutilization rates. As a consequence, there are very large differences in labor underutilization rates across combinations of educational attainment/household income groups among workers, both overall and within each gender and race-ethnic group (see Table 7A.4).

Forty-four percent of low-income workers who lacked a high school diploma were underutilized in 2013–2014 (Table 7A.4). As educational attainment rose, even low-income workers were less likely to experience such labor market problems. Among the nation’s most affluent workers with a master’s or higher degree, only 3.2 % were underutilized in 2013–2014. The absolute percentage point gap between these two radically different groups of workers was 41 percentage points, or 14 times in relative terms. For each gender and race-ethnic group, the relative difference in labor underutilization rates between these two groups of workers was in the double digits range and came close to or exceeded 15 times for men, Black, White, non-Hispanic workers, and other races, including Native American and those of mixed races. Tables 7A.5, 7A.6, 7A.7, 7A.8, 7A.9, 7A.10, and 7A.11 break down the labor underutilization rates of gender and race-ethnicity separately by household income level and education. Tables 7A.12, 7A.13, and 7A.14 display labor force underutilization rates of Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic White workers broken out by poverty, poverty/near poverty, and low-income status in six educational groups.

Appendix 7B: Associations Between Educational Attainment/Household Income by Gender and Race-Ethnic Groups

Findings on the unemployment rates of workers have focused on the links between educational attainment/household income and unemployment status for all workers combined. We also looked at the associations between educational attainment/household income and unemployment status to see whether they prevailed among both gender groups and across major race-ethnic groups. We estimated unemployment rates of workers in seven selected educational attainment/household income groups by gender and for Black, Hispanic, and White non-Hispanic workers. Key findings are displayed in Table 7B.1.

For men and women, the unemployment rate patterns were very similar. Both male and female workers with limited formal schooling and low incomes faced extremely high unemployment rates ranging from 21 to 24 %, while those with a high school diploma and below average incomes ($20,000–40,000) encountered unemployment rates between 8 and 10 %, and those with a bachelor’s or higher degree and incomes above $100,000 experienced unemployment rates of 2 %.

In the aggregate, unemployment rates across these three major race-ethnic groups varied from a low of 5.5 % among White non-Hispanics to a high of 12.3 % among Black non-Hispanics. In each race-ethnic group, however, the unemployment rates of workers were strongly linked to their educational attainment and household incomes. Among low-income high school dropouts and high school graduates with no college, unemployment rates varied from 16 to 38 %. They fell steadily and steeply with additional education and income for each race-ethnic group, falling to 6–8 % for those with some college and low-middle incomes to lows of 1–2 % for affluent workers with a master’s or higher degree. These gaps in unemployment rates across workers by schooling/household income were substantial for each race-ethnic group.

Appendix 7C: Logistic Probability Models Showing Effects of Demographics on Underutilization Rate of Workers

We have estimated a set of logistic probability models to illustrate the independent effects of various demographic variables on the underutilization rates of workers in 2013–2014.

The dependent variable in this logistic probability model is UNDERUTIL, a dichotomous variable that takes on the value of 1 if the respondent was underutilized at the time of the CPS and the value of zero if he or she was an active member of the labor force but was not underutilized.Footnote 22 The right-hand side predictor variables include the gender, age, race-ethnic origin, nativity status, disability status, educational attainment, and the annual family income category of the household. The base group of labor force participants for this analysis consists of White non-Hispanic, native born males, who were 55–64 years old, faced no physical or mental disability limiting their work ability, held a bachelor’s or higher degree, and lived in a family with an income above $150,000. Members of the base group faced an expected probability of being underutilized of 4 %. Definitions of each of these predictor variables are displayed in Table 7C.1.

The findings of the logistic probability regression displayed in Table 7C.2 reveal that the probability of a labor force participant being underutilized in 2013–2014 was significantly associated with age, race-ethnicity, disability status, educational attainment, and family income background (see Table 7C.2).Footnote 23 The youngest members of the labor force (those under 25 years of age) were significantly and substantially more likely than the older members of the base group (55–64) to be underutilized. Those participants 25–44 years of age (key members of the so-called prime aged work force) faced a labor underutilization probability less than three percentage points above the base group. Older adults (65 and over) faced a 1.8 percentage point greater probability of being underutilized relative to the base group of 55–64 year olds.

The gender of respondents had only a modest independent impact on the likelihood of being underutilized. Women with traits similar to those of men were about one percentage point more likely to be underutilized than males. Members of each minority race-ethnic group were more likely to be underutilized than comparable, White non-Hispanic peers; however, the impact was substantially higher for Black non-Hispanics than for Asians or Hispanics. Holding all other background traits constant, Black labor force participants were nearly 8.4 percentage points more likely than White non-Hispanics to be underutilized in the labor market.

The educational attainment of these labor force respondents had strong independent impacts on their probability of being underutilized. Relative to members of the base group who held a bachelor’s or higher degree, persons in each other educational group were more likely to be underutilized, with the size of the impacts being considerably higher for the less educated. High school students were nearly 20 percentage points more likely to be underutilized than four-year or higher college graduates. High school dropouts were between 14 and 15 percentage points more likely to be underutilized than those with bachelor’s or higher degrees. The likelihood of being underutilized fell to seven percentage points for high school graduates and to only two percentage points for those holding an associate’s degree.

The annual family income of the respondent had significant impacts on their probability of being underutilized in the labor market. Relative to the affluent members of the base group (those living in families with incomes above $150,000), members of each other income group were significantly more likely to be underutilized, with the size of these impacts declining with family income. Those labor force participants living in the lowest income households (an annual income under $20,000) were 32 percentage points more likely to be underutilized than the most affluent group. This impact fell to 18 percentage points for those in families with incomes between $20,000 to $40,000, to 10 percentage points for those with incomes between $40,000 and $75,000, and to only 2–5 percentage points or less for those with family incomes between $75,000 and $150,000.

Appendix 7D: Estimating the Probability of a Person with Given Background Traits Being Underutilized in 2013–2014

The logistic regression coefficients can be used to estimate the probability of a person with given characteristics being underutilized in 2013–2014. The procedure for estimating the probability of a person being underutilized with given traits is relatively straightforward. The probability that a given person being underutilized is equal to the following:

To calculate the values of Pi, we begin by calculating the value of α + βx for an individual with given traits, X i (e.g., gender, race-ethnic origin, age, education, nativity, disability, family income level). The values of the α and β’s are those generated by the logistic regression model. We then calculate the value of eα+βxi. The value of the denominator is simply equal to 1+ eα+βxi. The ratio of these two values would then yield the estimated probability of college attendance for this individual.

Appendix 7E: Logistic Probability Model of Labor Underutilization for Labor Force Participants Under 30

The following are details regarding estimates of a logistic probability model of labor underutilization among labor force participants under 30 in 2013–2014 (see Table 7E.1). The base group for this analysis is a 25- to 29-year old White non-Hispanic male who was not disabled, held a bachelor’s or higher degree and lived in a family with an income over $150,000.Footnote 24

Similar to our findings for all working-age adults (16 and over), gender had only a very modest impact on the labor underutilization rate of teens and young adults. Holding all other demographic and socioeconomic traits constant, young women were slightly under one percentage point less likely than males to be underutilized.Footnote 25 Teens and young adults (20–24 years old) faced much higher rates of labor underutilization than their older peers (25–29 years old). A teen labor force participant (or a member of the labor force reserve) was nearly 11 percentage points more likely than his or her peers 25–29 years old to be underutilized, while a 20–24 year old was about six percentage points more likely to be underutilized than his older peers.

Members of each race-ethnic group were significantly more likely than White non-Hispanics to be underutilized. The estimated sizes of these independent impacts of race-ethnic group varied from lows of two to three percentage points among Asians and Hispanics to a high of nine percentage points among Black non-Hispanic youth. The educational attainment of these youth also had frequently strong impacts on the probability of being underutilized at the time of the 2013–2014 surveys. Relative to their base group peers with a bachelor’s or higher degree, those young adults who lacked a high school diploma or GED were nearly 14 percentage points more likely to be underutilized. High school graduates were 10 percentage points more likely to be underutilized than bachelor’s degree holders. The impact drops to only 5 percentage points for those with 13–15 years of schooling but no degree and to under three percentage points for those with an associate’s degree.

Family income of respondents also affects an independent impact on the probability of young adults being underutilized in the labor market, but the negative impacts are primarily concentrated among low-income and low-middle-income youth. Those young adults with household incomes under $20,000 had a probability that was 12 percentage points higher of being underutilized than their affluent peers, and those young adults with incomes between $20,000 and $40,000 had a five to six percentage point higher probability of experiencing an underutilization problem. There were no significant differences between upper-middle-income youth and the most affluent families.

The above findings illustrate quite dramatically that among the young as well as among all workers, age, race-ethnic origin, educational attainment, and family income status played jointly large roles in shaping the incidence of underutilization problems in 2013–2014.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/) which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 Educational Testing Service

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Khatiwada, I., Sum, A.M. (2016). The Widening Socioeconomic Divergence in the U.S. Labor Market. In: Kirsch, I., Braun, H. (eds) The Dynamics of Opportunity in America. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25991-8_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25991-8_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-25989-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-25991-8

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)