Abstract

There is a considerable shortage of improved seed in Ethiopia. Despite good reasons to invest in this market, private sector investments are not occurring. Using an institutional economics theoretical framework, this chapter analyzes the formal Ethiopian seed system and identifies transaction costs to find potential starting points for institutional innovations. Analyzing data from more than 50 expert interviews conducted in Ethiopia, it appears that transaction costs are high along the whole seed value chain and mainly born by the government, as public organizations dominate the Ethiopian seed system, leaving little room for the private sector. However, recent direct marketing pilots are a signal of careful efforts towards market liberalization.

An earlier version of this chapter has previously been published as: Husmann C (2015) Transaction costs on the Ethiopian formal seed market and innovations for encouraging private sector investments. Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture Vol. 54(1):59–76

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

About 80 % of the Ethiopian popu lation depend as smallholder farmers on agriculture for their livelihoods (CSA 2012a). These smallholders suffer from a very low productivity (see, e.g., Seyoum Taffesse et al. 2011). To increase productivity, improved inputs like seeds, fertilizer and better farming practices are crucial (see, e.g., von Braun et al. 1992; Conway 2012).

Despite the presence of several seed companies, the agricultural input sector in Ethiopia is currently unable to satisfy the demand for improved seed in the country (Ministry of Agriculture (MoA) 2013). However, there are several reasons to invest in Ethiopian agricultural input markets: not only is the market large in terms of the number of people, high rates of economic growth and investments in infrastructure indicate huge potential, especially in the middle and long runs. Furthermore, in the last two decades, innovative business approaches have emerged that add social as well as financial returns to a company’s bottom line, and thus augment the reasons for companies to invest in poor countries and poor people (Baumüller et al. 2013).

Empirical studies suggest that the current situation in Ethiopian agricultural input markets is not the efficient outcome of demand and supply m eeting at a certain price, but that institutions drive up transaction costs, i.e., the “costs of coordinating resources through market arrangements” (Demsetz 1995, p. 4), leading to insufficient supply of and unmet demand for agricultural inputs (Alemu 2011, 2010; Bishaw et al. 2008; Louwaars 2010; Spielman et al. 2011). From a theoretical perspective of allocation, this situation is a market failure, since the lack of supply of agricultural inputs at current prices implies welfare outcomes below an achievable optimum. Thus, the current lack of inputs can be defined as a market failure in this sense (see Arrow 1969; Bator 1958 for detailed discussions of this argument).

Market failures are a result of high transaction costs. Transaction costs , however, are determined by the institutional structure of an economy (North 1989). North (1990) defines institutions as “the rules of the game in a society, or more formally, the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction” (North 1990, p. 3).

The free market cannot serve as the fictive first best option whose approximation can guide the design of an institutional setting, since transaction costs drive a wedge between producer and consumer prices such that, even in theory, ‘free markets’ do not lead to Pareto efficient results when transaction costs are taken into account (Arrow 1969; Demsetz 1969). Thus, a comparative approach evaluating real alternative institutional arrangements based on the identification of the relevant transaction costs that determine economic performance is appropriate for studying transaction costs and the functioning of markets (Williamson 1980; Demsetz 1969; Acemoglu and Robinson 2012).

Against this background, an analysis of the institutional setting and the transaction costs arising for agricultural input markets is carried out to get a better understanding of the reasons for the observed market failure and to assess possible solutions for th ese frictions. Only if these costs are reduced is there a chance that the private sector can expand activities to make improved seed accessible to the poor as well.

Transaction cost economics has been applied to study many different problems of economic organization. Masten (2001) stresses the importance of transaction cost economics for the analysis of agricultural markets and policy , as well as vice versa, the potential that the analysis of agricultural markets has for refining transaction cost theory (see also Kherallah and Kirsten 2002).

Transaction costs are generally found to be high on agricultural markets in poor countries and have a considerable influence on farmers’ marketing decisions. Several studies show that transaction costs are closely related to distance and that distance from markets negatively influences market participation and thus incomes (Alene et al. 2008; de Bruyn et al. 2001; Holloway et al. 2000; Kyeyamwa et al. 2008; Maltsoglou and Tanyeri-Abur 2005; Ouma et al. 2010; Rujis et al. 2004; Somda et al. 2005; Staal et al. 1997; Stifel et al. 2003). More specifically, Staal et al. (1997) find that transaction costs rise in greater proportion than transportation costs due to factors such as increasing costs of information and risk of spoilage of agricultural products. Furthermore, costs of information and research are found to impact smallholders’ marketing decisions (Gabre-Madhin 2001; Staal et al. 1997; de Bruyn et al. 2001; De Silva and Ratnadiwakara 2008; Kyeyamwa et al. 2008; Key et al. 2000; Maltsoglou and Tanyeri-Abur 2005).

However, Holloway (2000) and Staal et al. (1997) find a positive effect from organizations of collective action, such as cooperatives, in reducing transaction costs. These benefits accrue to both producers and buyers, as cooperatives reduce the cost of information for both sides and take advantage of economies of scales in collection and transport.

Less is known about transaction costs arising on the side of the private sector when companies try to market to poor smallholders. Recent studies engaged in initial analysis of constraints for companies entering agricultural markets in poor countries remain vague, but indicate that “(a) laws, policies or regulations that constrain business operations; (b) government capacity to respond quickly; and (c) access to capital” are the main hurdles named by the private sector to realizing investments in African agriculture (New Alliance for Food Security & Nutrition 2013, p. 6).

Against this background, the following chapter begins to fill this knowledge gap by analyzing the institutional setting and the resulting transaction costs that arise when selling improved seed to poor farmers in Ethiopia. The study uses primary data obtained through expert interviews that were conducted by the author in Ethiopia in 2011, 2012 and 2013. These interviews are analyzed concerning the importance of different types of transaction costs in providing incentives and disincentives to expand seed production. To ensure anonymity for the informants, only the stakeholder group of the informant is provided in the text in square brackets. Thus, if one or more experts from a stakeholder group provided information , this is indicated in the citation in the following way: [1] manager of an international seed company; [2] manager of a private Ethiopian seed company; [3] manager of a public Ethiopian seed company; [4] member of a farmer’s organization; [5] government employee; [6] employee of a public research organization; [7] employee of another organization (banks, Agricultural Transformation Agency, etc.).

Results show that the formal Ethiopian seed system is largely controlled by the government and public organizations. Based on a de facto monopoly of breeder seed, the government forces seed companies to market all seed through one government-controlled distribution channel, at prices determined by the government. This limits profit margins and incentives to expand seed production. The only exception to this system are the international seed companies that operate in Ethiopia, as these produce their own varieties and are thus not dependent on the breeder seed provided by the public research institutions. Thus, the government bears especially high transaction costs to sustain a system that does not lead to satisfactory outcomes. However, direct marketing pilots have been started that allow Ethiopian seed companies to market their seed directly to farmers for the first time, which may indicate a first step towards market liberalization.

Seed Production in Ethiopia

In the following, only the case of seeds of major crops is discussed. These major crops are 18 crops selected by the Ethiopian government: teff, barley, wheat, maize, sorghum, finger millet, rice, faba (fava) bean, field pea, haricot bean, chickpea, lentil, soybean, niger seed, linseed, groundnut, sesame and mustard. Institutions differ for other seeds, such as fruit and vegetable seeds, and for other agricultural inputs like fertilizer or agrochemicals. However, due to space l imitations, only the circumstances concerning the 18 major crops are discussed below.

Only 2.9 % of the farmers in Ethiopia reported using improved seed in 2011 (CSA and MoFED 2011, p. 20). The contribution of the formal seed sector as a percentage of cultivated land was only 5.4 % in 2011, with considerable variability among different crops (Spielman et al. 2011). Low technology adoption rates can occur for many reasons (Degu et al. 2000; Feder and Umali 1993). In Ethiopia, one important reason is the substantial lack of improved seed (see MoA 2013).

In 2011/2012, seed supply covered only 51 % of stated demand for barley, 24 % for wheat, 16 % for rice, 30 % for millet and 60 % for faba bean (MoA 2013). The supply of maize, wheat and teff seeds has improved considerably over recent years. But still, only 20 % of the area cultivated with maize, 4 % of the wheat area and less than 1 % of the teff area are cultivated with seed from the formal sector (CSA 2012b).

In the Ethiopian case, it is important to distinguish between different types of seed companies. Generally, in this chapter, a private seed company is understood as a firm with a business and a seed producing license, producing seed on its own account and bearing the full risk of the business. Thus, cooperative unions or farmers employed as seed producers by seed companies, or other organizations such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs ), do not fall into this category. However, this does not imply that seed companies produce all their seed themselves, companies can also hire farmers to produce the seed on their behalf.

For the following analysis, it is helpful to differentiate between public seed enterprises, private Ethiopian seed enterprises and international (private) seed enterprises . There are five public seed companies in Ethiopia: the Ethiopian Seed Enterprise (ESE) , the Amhara Seed Enterprise (ASE ) , the Oromia Seed Enterprise (OSE), the South Seed Enterprise (SSE) and the Somali Seed Enterprise. The ESE was the only seed company in the country for several decades before some private seed companies entered the market. The regional public seed enterprises were established recently, starting with ASE and OSE in 2009. Their statutes foresee them producing different kind of seeds for Ethiopian farmers without profit-making being a primary goal (Amhara Regional State 2008).

The number of private Ethiopian seed enterprises is not clear. In 2004, 26 firms were licensed to produce seed but only eight firms were active in seed production (Byerlee et al. 2007). Other sources mention 33 seed producing companies but without specifying who they are (Atilaw and Korbu 2012). In 2011, 16 private seed enterprises were listed in the business directory, but it is not clear whether they were all operating at that time.

Two international seed enterprises are producing some of the selected major crops (as at July 2013), Hi-Bred Pioneer and Seed Co. Both focus on the production of hybrid maize, while one of them also produces smaller quantities of wheat, teff and beans ([1]).

Why Is There Not More Investment in Seed Production?

If the stated demand is much higher than seed production, the question arises as to what is preventing private seed companies from increasing investments in seed production to tap this market. The answer to this question lies in the institutional setting governing seed production and distribution in Ethiopia.

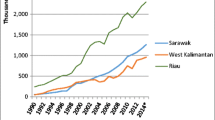

As illustrated in Fig. 8.1, the Ethiopian seed system is quite complex. The process of seed production starts with an assessment of seed demand, which is carried out by the Development Agents (DAs) on kebele (village) level. Information about seed demand is then passed up the governmental administrative ladder and collected by the Bureaus of Agriculture (BoA) and the MoA . On the basis of this information, the MoA orders production of quantities of various crops at the ESE, while the BoAs determine production portfolios for the regional public seed enterprises and the private seed companies in the area.

All Ethiopian seed companies – public and private – get their pre-basic and basic seed from public research institutes (see also Fig. 8.1). Only the two international seed companies operate with their own varieties. This is of great importance, because getting pre-basic seed from national research institutes comes with a contract entailing a clause that obliges the companies t o sell all produced seed back to the government – at prices to be determined by the government and often announced on short notice.

The MoA determines the quantities of seed to be distributed to each region on the basis of the demand assessment; the BoAs define the quantities for each zone, and so forth. Seed distribution is usually managed by farmer cooperative unions, who bring the seed to the zones and the primary (multipurpose) cooperatives that pick the seed up in the zonal warehouses and bring it to the woredas (districts) and kebeles. Unions charge for transport, uploading and unloading, but they make only small profits from seed distribution, with profit margins being determined by the regional governments ([3]; [4]).

An important implication of this seed system is the lack of agro-dealers , as seed distribution is organized in one government-controlled distribution channel. This also has important implications for other agro-dealers, as it makes it extremely difficult and expensive for them to market agricultural inputs outside larger agglomerations.

The private seed enterprises in Ethiopia mainly focus on hybrid maize production because it offers the highest profit margins. For this reason, supply of hybrid maize seeds has improved considerably since the regional seed enterprises started operation, from 88,000 quintals in 2006/2007 to 357,000 quintals (1 quintal = 100 kg) in 2010/2011 (Dalberg Global Development Advisors 2012). Private companies now produce about 40 % of the hybrid maize seed sold in the country (Alemu 2011).

Some companies also produce varieties of wheat, teff, beans, rice, soybean, sesame and sorghum. But all of these crops except hybrid maize are only produced in very small quantities, despite large cultivation areas. Thus, there are large untapped markets for these crops where demand is substantially higher than supply (see Table 8.1; MoA 2013). However, with the limited size of land for seed production, companies focus on the production of the seed with the highest profit margin as long as there is demand for that seed.

Institutions Preventing the Private Sector from Increasing Seed Production

Various institutions in the current seed system prevent private seed companies from increasing seed production and making it available to smallholders. Important constraints for the private Ethiopian seed enterprises result from the fact that none of them do their own breeding. Some managers express the intent of importing new parental lines for breeding to escape the strict government interference. However, breeding is a difficult business that requires additional land and high-skilled and experienced plant breeders , as well as technical facilities. Accordingly, seed producers need to get more land assigned by the government to start their own breeding, which takes a long time and is insecure. Additionally, it is difficult to hire experienced plant breeders in Ethiopia because, currently, plant breeders are government employees enjoying secure jobs and other privileges. Thus, it is difficult to attract them to private companies. This problem is aggravated by the fact that areas dedicated to plant breeding are always remote because breeding requires isolated land plots. These circumstances oblige companies to pay high salaries to plant breeders, since skilled people often do not want to live in remote areas ([2]). Moreover, the installation of the necessary technical facilities requires additional working capital, which is difficult to get.

On the other hand, several experts assume that some seed enterprises are quite content with the present form of the contracts, because they minimize risks as long as the government commits itself to buying all produced seed ([7]).

Another institution disadvantaging p rivate Ethiopian seed companies is related to the distribution of seed. Farmers can select the varieties they want to purchase, but they are usually not given the choice to opt for one particular source. It even often happens that the farmer cooperative unions or the primary cooperatives mix seed or refill bags from one seed with another to make transportation easier, which confuses farmers about the quality of seed of different producers ([2]). Two problems arise as a result: first, this prevents companies from establishing a brand name, and second, it hampers response to complaints by farmers about seed quality because the producer of the seed is not clearly identifiable.

Price determination is another point posing major difficulties for the private Ethiopian seed companies. Compared to other Sub-Saharan African countries , the seed prices determined by the government are relatively low in Ethiopia. At first glance, this seems to be beneficial for the farmers but it also has considerable disadvantages concerning users’ efficiency (Alemu 2010, p. 24) and can lead to a crowding out of the private sector ([2]). The prices of major crop seeds are negotiated by the BoAs, the board and the management of the public seed enterprises. These prices are then binding for maximum prices for the seed of all Ethiopian seed enterprises. Prices are based on estimations of farmers’ willingness to pay for seed, but there is no systematic assessment of farmers’ willingness or ability to pay (Alemu 2010). Prices vary considerably across regions and from year to year. In 2011, e.g., hybrid maize BH-540 was sold at 2000 Ethiopian Birr (ETB) per quintal in Oromia, while in Amhara, the price was 1500 ETB per quintal ([2]; [3]). In the 2010–2011 cropping season, Pioneer Hi-Bred sold its hybrid maize at 2784 ETB per quintal and sold all its stock ([1]).

What Is the Nature of Transaction Costs Arising in the Ethiopian Seed System?

Although it is not possible to quantify transaction costs resulting out of the presented institutions in the seed system, since neither the companies nor the government keep detailed records of their costs, the nature of the transaction costs involved and the distribution of these costs can be identified.

Costs for market entry have not been high in the past. Until now, it was not difficult for private companies to start a seed business. Business owners need (1) an investment license, (2) a competence license and (3) a business license if they produce the seed on their own land. If the company does not operate on its own land but hires farmers to produce the seed, it does not need the business license. Requirements to get the licenses are clear and the application procedure usually takes only a few weeks ([2]). However, private sector stakeholders fear that procedures will become more tiresome and lengthy, as the government might want to suppress additional competition for the regional public seed enterprises ([2]).

International seed enterprises that bring their own varieties face very high transaction costs for market entry ([1]). Bureaucratic procedures are unclear and lengthy. New varieties that are brought to the country need to get registered in a procedure that usually takes 3–4 years ([1]; Dalberg Global Development Advisors 2012).

Costs for market information and pricing are moderate, since demand is still very high for improved seed of all crops. For international seed companies marketing their own varieties, considerable costs arise for promotional activities, since it takes several years to gain the farmers’ confidence in a new brand. Many field days, demonstration plots and gratis seed packages are needed to convince farmers of the benefits of improved seed ([1]).

For Ethiopian seed enterprises, pre-contractual activities are organized by the government. Although there is no law or regulation fixing it, a de facto monopoly of the public research institutes implies a monopsony for seed, as the government obliges the seed companies to sell all seed back to it. The government is then responsible for the marketing of the seed. In terms of transaction costs, this means that, for the companies, costs for searching for customers and costs for information about the market do not arise, because their product portfolio is largely determined by the government and they have to sell the produced seed to the government. This is changing with the direct seed marketing pilots (see next section), in which companies are responsible for demand assessment themselves.

Advertisement costs do not arise for Ethiopian seed companies, since marketing is done by the government with the help of farmers’ cooperatives, and farmers cannot chose the source of their seed.

For the government, pre-contractual transaction costs are considerable. Government employees spend much time collecting data about seed demand and distributing seed. The typical time the head of extension in a woreda spends on collecting seed demand per season is 1 month, i.e., 2 months a year for both cropping seasons, and 45 days on distributing seed to the farmers ([5]). In the regional BoA of the Southern National, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region (SNNP ), for example, five full-time employees are charged with organizing seed supply and distribution ([5]). Additionally, employees in the zonal departments of agriculture and in the MoA are involved, but it is not clear how many people dedicate their working time to seed distribution there.

Contract formation (bargaining) is similarly simplified for companies, since the prices of major crop seed are negotiated by the BoA, the board and the management of the public seed enterprises. Since government regulations avoid direct contact and contracts between seed companies and farmers, there is no room for negotiations between customers and companies about prices or other parts of the contract ([2]).

The post-contractual transaction activities of contract execution, control, and enforcement are also minimized for seed companies by the actual government regulation. The theory of self-enforcing agreements (Furubotn and Richter 2005) ceases to be valid, since the seller of the seed is not the producer and complaints are usually not transferred back to the producer. The farmer cannot retaliate by ceasing to purchase the product if the product turns out to be of bad quality because, first, he cannot identify the producer, and secondly, because he cannot choose between different producers, such that the only alternative is not to buy improved seed at all.

As a result, it appears that, in the current situation, transaction costs are mainly born by the government. Governmental agencies assess demand and organize distribution of seed, and public banks finance the time elapsed between seed delivery by the seed enterprises and payments of the farmers. Promotional activities are done by the DAs, if at all. These transaction costs are very high and are not justified by satisfying outcomes in terms of quantities of seed produced, seed quality and timeliness of delivery.

Rather, the system has considerable disadvantages : cooperatives have to carry the burden of transporting seed, which keeps them away from other tasks, such as training for farmers or output marketing, on which they should actually focus ([7]). The current distribution network is also the reason for the lack of agro-dealers in the country, which is detrimental for the international seed companies and for other traders of agricultural inputs.

The Direct Seed Marketing Pilots

Increased pressure from private seed companies and other stakeholders led to the first trials in which Ethiopian seed companies could directly sell their seed to farmers. Starting in the Amhara region in 2011 and followed by Oromia and SNNP in 2012, Ethiopian seed companies were allowed for the first time to directly market their seed. These pilots have been scaled up in 2013. While in Amhara and Oromia, the direct seed marketing was restricted to hybrid maize, other varieties such as wheat could also be directly marketed in five woredas in SNNP.

Preliminary results of the Amhara pilot suggest that seed availability and timely delivery was better in project woredas than in non-project woredas (Astatike et al. 2012). The pilot also revealed that demand estimations for the pilot woredas were quite inaccurate. The project was not reiterated in Amhara in 2012, since the ASE was left with a lot of unsold seed that the government decided to sell preferentially in 2012 in the framework of the normal seed distribution system.

Concerning the 2012 direct seed marketing pilot in Oromia and SNNP, preliminary results indicate that all companies were able to sell almost all their seed. Participating companies in both regions even felt that they could have sold more seed if they would have had better demand information and fewer difficulties with transportation and storage in the woredas ([2]; Benson et al. 2014).

Still, in both woredas, more improved seed was sold than in any other year before, and more than was initially foreseen (ISSD 2013). This might have various reasons. First, the shops of agro-dealers were open 7 days a week and during the whole day, while the cooperatives distributing the seed usually only open for two afternoons a week due to the lack of full-time employees. Secondly, seed was available on time before planting and until planting was finished. Thus, previously well-known problems of late arrivals of seed were avoided. Third, agro-dealers are said to provide good technical advice to farmers. This, together with some promotion by the companies, might have increased awareness and trust in the seed. Finally, some farmers reported that they also bought seed for their relatives living in neighboring woredas who saw the benefits of early seed arrival and technical advice from the agro-dealers ([2]; [5]).

The main benefits of the pilots can be summarized as:

-

Traceability of the seed, and thus increased accountability for seed quality, which increases farmers’ trust;

-

Time resources saved by DAs and Subject Matter Specialists, who were previously occupied with seed distribution and can now concentrate on training and advisory services for farmers;

-

Farmers do not hold DAs responsible for seed failure, since seed distribution is now managed by agro-dealers, which considerably improves the relationship between DAs and farmers;

-

Companies are rewarded for better quality, and thus have an incentive to improve on quality in the future;

-

There is less seed fraud and storage damage as the value chain is much shorter.

The direct seed marketing trials can be seen as an important step towards market liberalization. However, the cessation of the pilot in Amhara shows how fragile such changes are. Improvements in the methodology and careful evaluations of the project will be needed to smooth the way towards market liberalization for companies, as well as for farmers.

Despite the generally very positive experience with the recent direct seed marketing pilots, some difficulties remain. An especially crucial point is the cost for transportation and agro-dealers. In 2012, sales prices were determined by the government and companies were not allowed to add up transportation costs and agro-dealer commissions, despite considerable expenses for long stretches of transport, which drove their profit margins towards zero or even below that. These problems led some companies to step out of the process. Other challenges are the lack of storage facilities in the woredas and a lack of trained agro- dealers.

Institutional Innovations to Improve Seed Supply and Access to Improved Seed

It can be doubted that the relationship between the sum of transaction costs and outcomes in terms of efficiency of seed production and distribution is optimal in the Ethiopian system. Of course, it is difficult to evaluate efficiency without a counterfactual. Yet, the analysis of the seed system reveals that institutions do not govern the seed market in an optimal manner: despite the high investments of time and other resources, inaccuracies in the demand assessments regularly lead to deficient outcomes that distort optimal seed production and distribution . High costs of capital and other burdens imposed by the government, e.g., concerning variety registration, prevent Ethiopian seed companies from investing in their own breeding, which could improve the availability of high-quality seed in the country. Incentives for optimizing seed quality are distorted, since farmers cannot identify the source of their seed and prices are independent from quality. Thus, access to pre-basic seed and/or support for their own breeding efforts, which would include the assignment of appropriate land plots and the availability of plant breeders and access to finance at reasonable costs combined with price incentives, could considerably improve incentives for private seed companies to increase production, and thus ameliorate the seed shortage in the country. The direct seed marketing pilots show that the government has recognized the need for change and may slowly deregulate the market.

To ensure supply of improved seed of all crops, contributions from the private sector will be needed. Even if the new regional seed enterprises expand and optimize their production in the near future, it is unlikely that they can satisfy the seed demand of all farmers in the country. This is also acknowledged by the government (World Economic Forum 2012).

In the current system, there is no strong incentive for many seed producers to begin making themselves more independent from the government. It is uncertain (for some even unlikely) that their profits would increase much, but business would become much riskier

To incentivize domestic as well as foreign investment, a well-designed and stepwise market liberalization is needed. Incremental institutional changes are required that provide incentives for the private sector to increase seed production and diversity in the product portfolio and to improve seed quality. Yet, the costs of such changes in terms of welfare losses of other stakeholders must be carefully evaluated. Some concrete innovations that are most likely to increase incentives for the private sector and result in better input supply for farmers in the middle- and long run are discussed below:

A central aspect for Ethiopian seed companies is that they need access to pre-basic seed of the varieties and in the quantities of their choice and the ability to market it in areas and at prices according to their firm strategy. Since public seed companies are not obliged to make profits according to their statutes, these enterprises can ensure that even the marginalized poor have access to improved seed in case the private companies develop strategies that focus on other market segments.

Microfinance institutions (MFIs ) or farmer cooperatives need to provide credits to the farmers. Without a credit facility, a rise in seed production will hardly benefit the majority of the peasants. MFIs are already serving many farmers but are still far from being omnipresent. However, extended coverage is needed to back up the want for improved inputs with purchasing power. The extension of coverage, however, needs to be accompanied by lending methodologies that ensure repayments to avoid the high default rates that have eroded the credit system in the past.

Access to credit is a decisive factor not only for the farmers but also for the seed companies if they are to increase seed production and the diversity of varieties. Collateral requirements and costs for negotiations with the banks need to be lowered such that seed companies have a rea listic chance of accessing finance at reasonable costs.

Another fundamental precondition for a more vibrant private sector is the assignment of more land for seed production and breeding efforts. Yet, more seed production and especially independent breeding efforts that would free Ethiopian companies from most governmental control along the value chain also require high-skilled plant breeders. The education of such people is a long-term task that needs to be taken care of by the government in the form of support for universities and higher learning institutes.

Additional to these ‘enabling changes’, it seems adequate to abolish the security for private seed enterprises that all produced seed is bought by the government. As long as seed companies do not need to use entrepreneurial spirit and design competitive firm strategies, many of them may remain in their cushy position in which no huge profits are made but the government organizes the marketing and covers much of the risks.

If seed markets are liberalized and the centralized distribution system is replaced by free market competition, access to seed for the poorest may be at stake. Thus, in a transition phase in which seed supply is not enough to meet demand and the private sector focuses on farmers who are better-off and easier to reach, the public seed enterprises can cater to the poorest, as, according to their statutes, they do not need to make profits. Alternatively, subsidies for the marginalized poor and investment incentives for companies may be temporary measures to ameliorate inequalities.

In the long term, however, private and public seed companies should compete for better quality and lower prices, both catering to the marginalized poor and to non-poor farmers. However, since the poor are the largest customer group in the country in terms of the number of people and, if they have access to credit, also in terms of the amount of inputs bought, it will be crucial for companies to cater to the poor if the largest part of the Ethiopian market is to be developed for the future.

How Can These Changes Be Brought About?

Having identified some potentially fruitful institutional innovations, the question arises as to how these changes could be brought about. It is unlikely that the private seed companies can establish a lobby group that bargains with one voice for market liberalization any time soon. Yet, to change institutions, a critical mass of agents is needed that together can reach a certain size in terms of market share or political importance and collectively work towards an institutional change (Acquaye-Baddoo et al. 2010). At the moment, the private seed companies do not seem to have this critical mass and it is not clear whether or how many of them really aim at changing the system.

Thus, while companies can still be expected to push for changes, the current situation and the self-conception of the Ethiopian government require the government to be in the lead. This then entails the question as to what could motivate the GoE to enact market liberalizing changes. Several factors may be important in this regard, most notably successful role models, support by other stakeholders and successes with investment incentive schemes in other sectors in the country.

Successful role models are certainly conducive for the government to enact changes. However, while neighbouring countries operate under similar initial conditions, so far, they have not successfully managed the transition to a liberalized market either (Ngugi 2002; Tripp and Rohrbach 2001). A more promising example would be China, which also comes closer to the development path aspired to by the Ethiopian government. China started from similar preconditions and was successful in increasing seed production by encouraging private sector investments and ensuring a division of labour between public and private enterprises for tasks like seed breeding and training of breeders (Cabral et al. 2006; Meng et al. 2006; Park 2008; Peoples Republic of China State Council 2013).

Not only the Chinese but also the German seed sector may be of some relevance for Ethiopia. The German seed industry is – similar to the Ethiopian case – built up of mainly medium-sized companies. About 130 plant breeding and seed trading companies operate in Germany, 60 of them with their own breeding programs. Most of the seed producing and trading companies are organized in regional associations and under a national umbrella association, the German Plant Breeders’ Association . This umbrella association is the central part of a network that serves as a platform for pre-competitive joint research projects, patent issues, and public variety testing, as well as for safeguarding plant variety protection (http://www.bdp-online.de/en/). The German example is relevant to the Ethiopian case in as much as it shows that market consolidation can be avoided (Fernandez-Cornejo 2004).

Apart from learning from role models, cooperation between governments can help to facilitate the entry of private companies into the market. Furthermore, support can be expected from international organizations like AGRA (http://agra-alliance.org) and the Integrated Seed System Development Project (http://www.issdethiopia.org), or initiatives like the New Vision for Agriculture, the New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition and Feed the Future (http://www.feedthefuture.gov) that are ready to support the government in market liberalization efforts .

In addition to these sources of support, cooperation and support from NGOs is needed as well. The distribution of free seed by relief organizations or even by public entities in the context of agricultural development programs has been identified as one of the most serious constraints to seed system development (Tripp and Rohrbach 2001).

And finally, successful experiences from other sectors of the economy, especially other subsectors of agriculture, may motivate the government to support private sector investments. Such positive experiences can be drawn from the flower sector, where investments have been attracted by the government. Thanks to these programs, flower production increased significantly in the last two decades (Ayele 2006; see also e.g. The Embassy of Ethiopia in China 2013).

Another very important factor is the change in informal institutions . In Ethiopia, many parts of society are still considerably shaped by the country’s socialist past. Entrepreneurial spirit is not very common ([5]), and scepticism concerning business and the belief in a state-directed economy are still common among government employees. But if the private sector is meant to increase operations, support needs to come from all levels of government and other parts of society, from universities to banks to consumers.

References

Acemoglu D, Robinson J (2012) Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty, 1st edn. Crown Publishers, New York

Acquaye-Baddoo NA, Ekong J, Mwesige D, Neefjes R, Nass L, Ubels J, Visser P, Wangdi K, Were T, Brouwers J (2010) Multi-actor systems as entry points for capacity development. Capacity.org. A gateway for capacity development, pp. 4–5

Alemu D (2010) Seed system potential in Ethiopia. Constraints and opportunities for enhancing the seed sector. International Food Policy Research Institute, Addis Ababa/Washington, DC

Alemu D (2011) The political economy of Ethiopian cereal seed systems: state control, market liberalisation and decentralisation. IDS Bull 42(4):69–77. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.2011.00237.x

Alene AD, Manyong VM, Omanya G, Mignouna HD, Bokanga M, Odhiambo G (2008) Smallholder market participation under transactions costs: maize supply and fertilizer demand in Kenya. Food Policy 33(4):318–328. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2007.12.001

Amhara Regional State (2008) Document for establishment of Amhara seed enterprise. Government of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

Arrow KJ (1969) The organization of economic activity: issues pertinent to the choice of market versus nonmarket allocation. In: The analysis and evaluation of public expenditure: the PPB system, vol 1. US Joint Economic Committee of Congress, Washington, DC, pp 59–73

Astatike M, Yimam A, Tsegaye D, Kefale M, Mewa D, Desalegn T, Hassena M (2012) Experience of direct seed marketing in Amhara region (unpublished report). Local Seed Business, Addis Ababa

Arrow KJ (1969) The organization of economic activity: issues pertinent to the choice of market versus nonmarket allocation. In: The analysis and evaluation of public expenditure: the PPB system, vol 1. US Joint Economic Committee, Washington, DC, pp 59–73

Ayele S (2006) The industry and location impacts of investment incentives on SMEs start-up in Ethiopia. J Int Dev 18(1):1–13. doi:10.1002/jid.1186

Bator FM (1958) The anatomy of market failure. Q J Econ 72(3):351. doi:10.2307/1882231

Baumüller H, Husmann C, von Braun J (2013) Innovative business approaches for the reduction of extreme poverty and marginality? In: von Braun J, Gatzweiler FW (eds) Marginality. Addressing the nexus of poverty, exclusion and ecology. Springer, Dordrecht/Heidelberg/New York/London, pp 331–352

Benson T, Spielman D, Kasa L (2014) Direct seed marketing program in Ethiopia in 2013. An operational evaluation to guide seed-sector reform. International Food Policy Research Institute, Addis Ababa

Bishaw Z, Yonas S, Belay S (2008) The status of the Ethiopian seed industry. In: Thijssen MH, Bishaw Z, Beshir A, de Boef WS (eds) Farmers, seeds and varieties: supporting informal seed supply in Ethiopia. Wageningen International, Wageningen, pp 23–31

Byerlee D, Spielman DJ, Alemu D, Gautam M (2007) Policies to promote cereal intensification in Ethiopia: a review of evidence and experience. IFPRI discussion paper 707, Washington, DC

Cabral L, Poulton C, Wiggins S, Xhang L (2006) Reforming agricultural policies: lessons from four countries. Futures agricultures futures agricultures working paper 002. Future Agricultures, Brighton

Conway G (2012) One billion hungry. Cornell University Press, New York

CSA (2012a) Household Consumption and Expenditure (HCE) survey 2010/11. Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa

CSA (2012b) Agriculture – 2011, national abstract statistics. Central Statistical Agency, Addis Ababa

CSA, MoFED (2011) Agricultural sample survey 2010–11. Study documentation. Central Statistical Agency and Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, Addis Ababa

Dalberg Global Development Advisors (2012) Amhara seed enterprise strategy refresh. Dalberg Global Development Advisors, unpublished document

De Bruyn P, de Bruyn JN, Vink N, Kirsten JF (2001) How transaction costs influence cattle marketing decisions in the northern communal areas of Namibia. RAGR 40(3):405–425. doi:10.1080/03031853.2001.9524961

De Silva H, Ratnadiwakara D (2008) Using ICT to reduce transaction costs in agriculture through better communication: a case study from Sri Lanka. LIRNEasia, Colombo

Degu G, Mwangi W, Verkuijl H, Wondimu A (2000) An assessment of the adoption of seed and fertilizer packages and the role of credit in smallholder maize production in Sidama and North Omo Zones, Ethiopia. International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, Mexico DF

Demsetz H (1969) Information and efficiency: another viewpoint. J Law Econ 12(1):1–22. doi:10.1086/466657

Demsetz H (1995) The economics of the business firm: seven critical commentaries. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Feder G, Umali DL (1993) The adoption of agricultural innovations. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 43(3–4):215–239. doi:10.1016/0040-1625(93)90053-A

Fernandez-Cornejo J (2004) The seed industry in U.S. agriculture: an exploration of data and information on crop seed markets, regulation, industry structure, and research and development. Agric Inf Bull AIB-786:1–81

Furubotn EG, Richter R (2005) Institutions and economic theory: the contribution of the new institutional economics, 2nd edn. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Gabre-Madhin E (2001) Market institutions, transaction costs, and social capital in the Ethiopian grain market. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Holloway G, Nicholson C, Delgado C, Staal S, Ehui S (2000) Agroindustrialization through institutional innovation transaction costs, cooperatives and milk-market development in the east-African highlands. Agric Econ 23:279–288. doi:10.1111/j.1574-0862.2000.tb00279.x

ISSD (2013) Direct seed marketing: additional channel to enhance seed marketing and distribution system in Ethiopia. ISSD, Addis Ababa

Key N, Sadoulet E, Janvry A (2000) Transactions costs and agricultural household supply response. Am J Agric Econ 82(2):245–259

Kherallah M, Kirsten JF (2002) The new institutional economics: applications for agricultural policy research in developing countries. Agrekon 41(2):111–134

Kyeyamwa H, Speelman S, van Huylenbroeck G, Opuda-Asibo J, Verbeke W (2008) Raising offtake from cattle grazed on natural rangelands in sub-Saharan Africa: a transaction cost economics approach. Agric Econ 39(1):63–72. doi:10.1111/j.1574-0862.2008.00315.x

Louwaars N (2010) The formal seed sector in Ethiopia. A study to strengthen its performance and impact. Local Seed Bus Newsl 3:12–13

Maltsoglou I, Tanyeri-Abur A (2005) Transaction costs, institutions and smallholder market integration: potato producers in Peru, ESA working paper. FAO, Rome

Masten SE (2001) Transaction-cost economics and the organization of agricultural transactions. In: Baye R (ed) Industrial organization, vol 9, Advances in applied microeconomics. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 173–195. doi:10.1016/S0278-0984(00)09050-7

Meng ECH, Hu R, Shi X, Zhang S (2006) Maize in China. Production systems, constraints and research priorities. International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, Mexico

Ministry of Agriculture (2013) Data on demand and supply of improved seed of different crops. MoA, Addis Ababa

New Alliance for Food Security & Nutrition (2013) New alliance for food security and nutrition 2013 progress report. DFID, AU Commission and WEF, London

Ngugi D (2002) Harmonization of seed policies and regulations in East Africa. In: Rohrbach D, Howard J (eds) Seed trade liberalization and agro-biodiversity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Presented at the workshop on impacts of seed trade liberalization on access to and exchange of agro-biodiversity, International Crop Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, Matopos Research Station, Bulawayo, pp. 101–120

North DC (1989) Institutions and economic growth: an historical introduction. World Dev 17(9):1319–1332. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(89)90075-2

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Ouma E, Jagwe J, Obare GA, Abele S (2010) Determinants of smallholder farmers’ participation in banana markets in Central Africa: the role of transaction costs. Agric Econ 41(2):111–122. doi:10.1111/j.1574-0862.2009.00429.x

Park A (2008) Agricultural development in China: lessons for Ethiopia. Briefing note prepared for the DFID funded study “understanding the constraints to continued rapid growth in Ethiopia: the role of agriculture”. DFID, London

Peoples Republic of China State Council (2013) National plan for development of the modern crop seed industry (2012–2020). Unofficial translation, Peoples Republic of China State Council, Beijing

Rujis A, Schweigman C, Lutz C (2004) The impact of transport-and transaction-cost reductions on food markets in developing countries: evidence for tempered expectations for Burkina Faso. Agric Econ 31(2–3):219–228. doi:10.1111/j.1574-0862.2004.tb00259.x

Seyoum Taffesse A, Dorosh P, Asrat S (2011) Crop production in Ethiopia: regional patterns and trends, ESSP working paper 0016. IFPRI, Addis Ababa

Somda J, Tollens E, Kamuanga M (2005) Transaction costs and the marketable surplus of milk in smallholder farming systems of the Gambia. Ooa 34(3):189–195. doi:10.5367/000000005774378784

Spielman DJ, Kelemwork D, Alemu D (2011) Seed, fertilizer, and agricultural extension in Ethiopia. Ethiopia Strategy Support Program II (ESSP II) 20. IFPRI, Addis Ababa

Staal S, Delgado C, Nicholson C (1997) Smallholder dairying under transactions costs in East Africa. World Dev 25(5):779–794. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(96)00138-6

Stifel DC, Minten B, Dorosh P (2003) Transactions costs and agricultural productivity: implications of isolation for rural poverty in Madagascar, IFPRI MSSD discussion paper 56. IFPRI, Addis Ababa

The Embassy of Ethiopia in China (2013) Horticulture and floriculture industry: Ethiopia’s comparative advantage [WWW Document]. http://www.ethiopiaemb.org.cn/bulletin/05-1/003.htm. Accessed 26 Feb 2014

Tripp R, Rohrbach D (2001) Policies for African seed enterprise development. Food Policy 26(2):147–161. doi:10.1016/S0306-9192(00)00042-7

von Braun J, Bouis H, Kumar S, Pandya-Lorch R (1992) Improving food security of the poor: concept, policy, and programs. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Williamson OE (1980) The organization of work a comparative institutional assessment. J Econ Behav Organ 1(1):5–38. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(80)90050-5

World Economic Forum (2012) Accelerating infrastructure investments – world economic forum on Africa 2012. http://www.weforum.org/videos/accelerating-infrastructure-investments-world-economic-forum-africa-2012. Accessed 16 Aug 2012

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/) which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Husmann, C. (2016). Institutional Innovations for Encouraging Private Sector Investments: Reducing Transaction Costs on the Ethiopian Formal Seed Market. In: Gatzweiler, F., von Braun, J. (eds) Technological and Institutional Innovations for Marginalized Smallholders in Agricultural Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25718-1_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25718-1_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-25716-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-25718-1

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)