Abstract

This chapter is divided into four parts according to an ideal division of the Tentamen. In the first part Leibniz dealt with harmonic circulation and introduced paracentric motion; in the second one he analysed the properties of paracentric motion; in the third one he dealt with the inverse square law and the elliptic movements of the planets; in the fourth one Leibniz provided a summary of his model. Every paragraph is divided into two subparagraphs: 1. Leibniz’s assertions; 2. commentaries.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

Translation drawn from Bertoloni Meli (1993, pp. 129–130). Original latin text: “Circulationem voco Harmonicam, si velocitates circulandi, quae sunt in aliquo corpore, sint radiis seu distantiis a centro circulationis reciproce proportionales, vel (quod idem) si ea proportione decrescant velocitates circulandi circa centrum, in qua crescunt distantiae a centro, vel brevissime, si crescant velocitates circulandi proportione viciniarum.” (Leibniz 1689, 1860, 1962, VI, pp. 149–150).

- 2.

Translation drawn from Bertoloni Meli (1993, p. 130). Original latin text: “Cum enim arcus isti elementarium circolationum sunt in ratione composita temporum et velocitatum, tempora autem elementaria assumantur equalia, erunt circulationes ut velocitates, itaque et velocitates reciproce ut radii erunt, adeoque circulatio dicetur harmonica.” (Leibniz 1689, 1860, 1962, VI, p. 150).

- 3.

LSB, III, 5, p. 337. Original French text: “Il est certain que les pesanteurs des Planetes estant posees en raison double reciproque de leurs distances du soleil, cela, avec la vertu Centrifuge, donne les Eccentriques Elliptiques de Kepler. Mais comment en substituant vostre Circulation Harmonique, et retenant la mesme proportion des pesanteurs, vous en deduisez les mesmes Ellipses, c’est ce que je n’ay jamais pu comprendre par vostre explication qui est aux Acta de Leipsich; ne voiant pas comment vous trouvez place à quelque espece de Tourbillon deferant de des Cartes, que vous voulez conserver; puisque la dite proportion de pesanteur, avec la force Centrifuge produisent elles seules les Ellipses Keplerienes selon la demonstration de Mr Newton. Vous m’aviez promis il y a longtemps d’eclaireir cette difficulté”.

- 4.

Aiton (1964, p. 112).

- 5.

Aiton (1972, p. 136).

- 6.

Huygens’ and Aiton’s aims are, however, different, which is obvious: Huygens seems to invite Leibniz to abandon the harmonic circulation, while Aiton has the intention to prove that the mathematical treatment of the paracentric motion is independent of harmonic circulation.

- 7.

Leibniz (1690a, 1860, 1962, VI, pp. 189–190). This is a letter written in October 1690 and edited by Gerhardt in Ivi, pp. 187–193. This letter was never sent to Huygens. On this see Aiton (1964, p. 114, note 16). Original French text: “El le même corps aussi est mû dans l’ether comme s’il y nageoit tranquillement sans avoir aucune impetuosité propre, ny aucun reste des impressions precedentes, et ne faisoit qu’obeïr absolument à l’ether qui l’environne […] Mais quelque autre circulation qu’on suppose hors l’harmonique, le corps gardant l’impression precedente […]”.

- 8.

Ivi, p. 192. See also Aiton (1964, pp. 113–115). Original French text: “Vous dirés peutestre d’abord, Monsieur que l’hypothese de quarrés des vistesses reciproques aux distances ne s’accorde pas avec la circulation harmonique. Mais la réponse ast aisée: la circulation harmonique se rencontre dans châque corps a part, comparant les distances differentes qu’il a, mais la circulation harmonique en puissance (où le quarrés des velocités sont reciproques aux distances) se rencontre en comparant des differens corps, soit qu’ils décrivent une ligne circulaire, ou qu’on prenne leur moyen movement […] pour l’orbe circulaire qu’ils décrivent”.

- 9.

Translation drawn from Bertoloni Meli (1993, p. 132). Original Latin text: “Hunc conatum metiri licebit perpendiculari ex puncto seguenti in tangentem puncti praecedentis inassignabiliter distantis.” (Leibniz 1689, 1860, 1962, VI, p. 152).

- 10.

Translation drawn from Bertoloni Meli (1993, p. 133). Original latin text: “ […] aequatur perpendiculari ex uno extremo arcus circuli puncto in tangentem alterius ductae […].” (Leibniz 1689, 1860, 1962, VI, p. 153).

- 11.

See Leibniz (1689, 1860, 1962, VI, paragraph 11, p. 153).

- 12.

Leibniz wrote “[…] differentia vel summa solicitationis paracentricae […] et dupli conatus centrifugi […]” (my italics, Leibniz 1689, 1860, 1962, VI, p. 154), referring to the double centrifugal conate and not to the simple centrifugal conate. This is a mistake highlighted by Varignon. For an explanation see next Sect. 2.2.2. Commentaries.

- 13.

Translation drawn from Bertoloni Meli (1993, p. 134). Original Latin: “Solicitatio paracentrica, seu gravitatis vel levitatis exprimitur recta M 3 L ex puncto curvae M 3 in puncti praecedentis inassignabiliter distantis M 2 tangentem M 2 L (productam in L) acta, radio praecedenti ΘM 2 (ex centro Θ in punctum precedens M 2 ducto) parallela”. (Leibniz 1689, 1860, 1962, VI, p. 154).

- 14.

I remind the reader that the two triangles are congruent because: a) \( {M}_3{D}_2={M}_1N \); b) they are right triangles; c) For the angles the following identities are valid: \( {M}_1{M}_2N={D}_2{M}_2L \) and \( {D}_2{M}_2L={D}_2G{M}_3 \), because of the parallels M 3 G and M 2 L. Thus, \( {M}_1{M}_2N={D}_2G{M}_3 \). Hence, the thesis follows.

- 15.

The explanation of the centrifugal force in terms of A) and B) could be called an inertial interpretation of a non-inertial reference frame. Historically, Leibniz did not resort to it. However, this explanation is useful to catch the situation from a physical point of view and to better understand the correct reasoning of Leibniz as to the centrifugal force.

- 16.

- 17.

The documents in which Newton and Keill criticized Leibniz are three: 1) Newton’s writing titled “Epistola cujusdam ad amicum“, published in Edleston 1850. Edleston claims that, probably this letter was written in 1712; 2) a second document sent by Newton to Keill and titled “Notae in Acta Eruditorum an. 89 p. 84 et sequ”, available in the University Library of Cambridge, Add. MS 3985 f. 6; 3) the only published work on this question, that is Keill (1714). Keill’s work is almost completely based upon Newton’s ideas. For a complete report on these critics, see Aiton (1962).

- 18.

Newton in Edleston 1850, p. 311. Original latin text: “Undecima Tentaminis Propositio est haec: Conatus centrifugus exprimi potest per sinum versum anguli circulationis. Et vera quidem est haec propositio ubi circulatio fit in circulo sine motu paracentrico. Sed ubi fit in Orbe excentrico propositio vera non est. Conatus centrifugus semper equalis est vi gravitatis et in contrarias partes dirigitur per tertiam motus Legem in Principiis Mathematicis Newtoni, et vis gravitatis esprimi non potest per sinum versum anguli circulationis, sed est reciproce ut quadratum radii”. Italics in the text.

- 19.

Ivi, p. 313. Original latin text: “Propositio vigesima (sic) prima et vigesima quinta, minorem exhibent vim centrifugam quam gravitatem Planetae in Solem ideoq: falsae sunt. Motus Planetae in orbe non pendet ab excessu gravitatis supra vim centrifugam (ut credit Leibnitius) sed Orbis incurvatur a gravitatis actione sola, cui vis centrifuga (ut reactio vel resistentia) semper est equalis et contraria per motus Legem tertiam a Newtono positam”.

- 20.

See Gregory (1702, pp. 99–104).

- 21.

Newton in Edleston 1850, p. 312.

- 22.

- 23.

In his work Nova Methodus pro Maximis et Minimis, itemque tangentibus […] (see Leibniz 1684, 1858, 1962, V, p. 223), Leibniz explicitly claimed that the tangent can be considered as the ordinary Euclidean tangent or as the prolongation of the side of the infinitangular polygon which can be thought as equivalent to the curve, at least as far as some mathematical considerations are concerned. For, Leibniz wrote: “to find the tangent is to draw the straight line which joins two points of a curve, whose distance is infinitely small, or the prolonged side of the infinitangular polygon, which, for us, is equivalent to the curve”. Original Latin text: “[…]tangentem invenire esse rectam ducere, quae duo curvae puncta distantiam infinite parvam habentia jungat, seu latus productum polygoni infinitanguli, quod nobis curvae equivalet.” (I am grateful to Professor Dr. Eberhard Knobloch for this indication). In the case I am analysing, the two representations of the tangent as ordinary tangent or as prolongation of the infinitangular polygon, are not equivalent as the mathematical consequences are different, according to which representation one uses. However: Leibniz had already spoken of the two representations, as the mentioned passage confirms, hence this makes Aiton’s interpretation quite plausible.

- 24.

Leibniz (1706, 1860, 1962, VI, p. 261). Original latin text: “Porro generatim concipiendo (fig. 31) duo Latera polygon curvam constituentis M 1 M 2 et M 2 M 3, et unum ex illis M 1 M 2 continuando in L ita, ut recta M 2 L celeritatem repraesentet, quo mobile post percursam M 1 M 2 in eadem recta pergere tendit[…]”.

- 25.

Varignon to Leibniz 6 December 1704 in Leibniz (1859, 1962, IV, pp. 113–127).

- 26.

Leibniz (1706, 1860, 1962, VI, pp. 264–266).

- 27.

- 28.

Up to now, the most complete report of the Zweite Bearbeitung is in Bertoloni Meli (1993, pp. 155–161).

- 29.

Leibniz (1790?, 1860, 1962, VI, p. 174). Original latin text: “Si quid moveatur in Ellipsi, velocitas circulandi circa focum est ad velocitatem paracentricam, nempe descendendi ad focum vel a foco recedendi, ut axis minor seu transversus est ad latus differentiae inter potestatem distantiae focorum inter se et potestatem differentiae distantiarum mobilis a focis”. At the end of the quotation, Leibniz used the Euclidean language to indicate the segments. I have provided a modern translation of “[…] ad latus differentiae inter potestatem distantiae focorum inter se et potestatem differentiae distantiarum mobilis a foci”. It is, obviously, possible to give a translation, which is more faithful to Euclid’s tradition: “[…] at the side of the difference between the power of foci’s distance and the power of the difference of mobile’s distances from the foci”.

- 30.

Leibniz (1790?, 1860, 1962, VI, p. 175). This is an important relation between the radial and transverse velocity, which, in modern terms, can be proved like this:

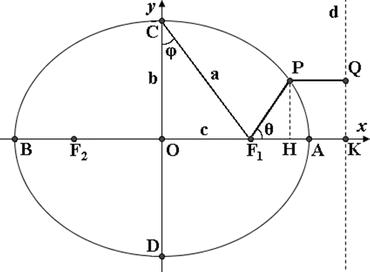

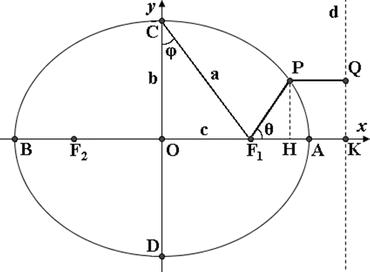

the radial velocity is \( {v}_r=dr/dt \) and the transverse velocity is \( {v}_{\theta }=r\cdot d\theta /dt \), therefore \( {v}_r/{v}_{\theta }=dr/r\cdot d\theta \). Since the orbit is an ellipsis, its polar equation is \( r=\frac{ed}{1+e \cos \theta } \), where e is the eccentricity and d is the distance F 1 K of the focus F 1 from the directrix d. Differentiating this expression one gets \( \frac{dr}{d\theta }=\frac{r^2 \sin \theta }{d} \); therefore \( \frac{v_r}{v_{\theta }}=\frac{r\mathrm{s}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\theta }{d} \); but d is a constant and rsenθ = PH; this is the corollary of Leibniz (diagram drawn from www.fmboschetto.it/tde2/gravit4.htm).

- 31.

The two theorems which Leibniz proved and used to prove the inverse square law by means of the conatus excussorius are: 1) in every straight line the solicitation of gravity M 2 G is at the excussorius conate M 2 K as M 3 G (that is M 2 M 3, which is the element of the curve or the orbital velocity) is at the velocity of circulation M 3 D 2 (Leibniz 1690?, 1860, 1962, VI, pp. 178–179); 2) in every line of motion, it is \( {M}_2K=\frac{M_3{K}^2}{SM} \), namely, to tell à la Leibniz: the conatus excussori are as the duplicate ratio of the orbital velocities directly and the simple ratio of the radii of the osculating circle inversely (Ivi, p. 179).

- 32.

Bertoloni Meli (1993, p. 159).

- 33.

In Newton’s Principia, one could speak of “infinitesimal geometry” because Newton needs the instantaneous physical quantities, but his resort to calculus is—at least explicitly—limited enough in his masterpiece. He provides geometrical demonstrations in which the infinitesimal segments and areas are described as part of a figure. Since in many cases these segments represent potentially infinite quantities, it is possible to speak of infinitesimal geometry. The literature on this subject is conspicuous. I provide here only five references in which the problem is faced and explained: Bussotti and Pisano (2014a), in particular pp. 35–37; Bussotti and Pisano (2014b), in particular p. 435; De Gandt (1995), Guicciardini (1998, 1999, 2009). Leibniz uses here a similar technique.

- 34.

Leibniz (1790?, 1860, 1962, VI, p. 180). Original latin text: “[…] prorsus ut antea in hoc ipso praesente articulo per viam diversam, nempe ope calculi nostri differentialis et theorematis articulo 15 propositi inveneramus”.

References

Aiton EJ (1960) The celestial mechanics of Leibniz. Annals of Science, 16, 2, pp. 65–82. 11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00033796000200059.

Aiton EJ (1962) The celestial mechanics of Leibniz in the light of Newtonian criticism. Annals of Science, 18, 1, pp. 31–41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00033796200202682.

Aiton EJ (1964) The celestial mechanics of Leibniz: A new interpretation. Annals of Science, 20, 2, pp. 111–123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00033796400203014.

Aiton EJ (1972) The vortex theory of planetary motions. American Elsevier Publishing Company, New York.

Bertoloni Meli D (1993) Equivalence and priority: Newton versus Leibniz. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Bussotti P, Pisano R (2014a) On the Jesuit Edition of Newton’s Principia. Science and Advanced Researches in the Western Civilization. Advances in Historical Studies, 3, 1, pp. 33–55. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ahs.2014.31005.

Bussotti P, Pisano R (2014b) Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica “Jesuit” edition: The tenor of a huge work. Rendiconti Lincei Matematica e Applicazioni, 25, pp. 413–444.

De Gandt F (1995) Force and Geometry in Newton’s Principia . Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Gregory D (1702) Astronomiae physicae et geometricae elementa. Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford.

Guicciardini N (1998). Did Newton use his calculus in the Principia? Centaurus, 40, 303–344. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0498.1998.tb00536.x

Guicciardini N (1999). Reading the Principia. The debate on Newton’s mathematical methods for natural philosophy from 1687 to 1736. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Guicciardini N (2009) Isaac Newton on Mathematical Certainty and Method, MIT Press, Cambridge (Mass.).

Keill M (1714) Response de M Keill, M. D. Professeur d’Astronomie Savilien aux auteurs des Remarques sue le Different entre M. de Leibniz et M. Newton, publiées dans le Journal Litéraire de la Haye de Novembre et Decembre 1713. Journal Litéraire, 4, pp. 319–352.

Leibniz GW (1684, 1858, 1962) Nova Methodus pro Maximis et Minimis, itemque Tangentibus, quae nec fractas nec irrationales quantitates moratur, et singulare pro illis calculi genus. In Leibniz ([1849–1863], 1958), V volume, pp. 220–226.

Leibniz GW (1689, 1860, 1962) Tentamen de Motuum Coelestium Causis (Erste Bearbeitung). In Leibniz ([1849–1863], 1962), VI volume, pp. 144–161.

Leibniz GW (1690?, 1860, 1962) Tentamen de Motuum Coelestium Causis (Zweite Bearbeitung). In Leibniz ([1849–1863], 1962), VI volume, pp. 161–187.

Leibniz GW (1690a, 1860, 1962), Beilage to the Tentamen (letter to Huygens). In Leibniz ([1849–1863], 1962), VI volume, pp. 187–193.

Leibniz GW (1706, 1860, 1962) Illustratio Tentaminis de Motuum Coelestium Causis, Pars I et Pars II plus Beilage. In Leibniz ([1849–1863], 1962), VI volume, pp. 254–280.

Newton I (1712?, 1850) Epistola cujusdam ad amicum, in Correspondence of Sir isaac Newton and Professor Cotes, including letters of other eminent men (Ed. J Edleston). Parker, London, pp. 308–314.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bussotti, P. (2015). Description of the Most Important Elements of Leibniz’s Planetary Theory. In: The Complex Itinerary of Leibniz’s Planetary Theory. Science Networks. Historical Studies, vol 52. Birkhäuser, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-21236-4_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-21236-4_2

Publisher Name: Birkhäuser, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-21235-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-21236-4

eBook Packages: Mathematics and StatisticsMathematics and Statistics (R0)