Abstract

Self-service technology could be argued as creating less personal transactions when compared to traditional checkouts involving a sales assistant for the entire transaction process, which may affect customer behavior. The aim of our study was to investigate the perceived influence of social presence at self-service checkouts by staff and its perceived effect on dishonest customer behavior. Twenty-six self-service checkout staff took part in a series of semi-structured interviews to describe customer behaviors with self-service. With respect to actual physical social presence, staff reported that more customer thefts occurred when the self-service checkouts were busy and their social presence was reduced. Staff also reported that perceived and actual social presence is likely to reduce thefts. Future research will elaborate to which extent the perceived social presence via technological systems might support staff in their task to assist customers and reduce dishonest behavior.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The wide implementation of self-service technology (SST) in retail provides a growing area of interest to assess social and psychological effects on consumers and staff. Retailers are replacing many traditional service delivery positions, usually conducted by a sales clerk, with self-service technology [21]. Such SSTs comprise technological interfaces that enable customers to engage in service transactions independent of direct employee involvement [9]. Self-service technologies can assist transactions such as placing an order, and scanning or paying for items [23], and can reduce costs and raise productivity, as they utilize the consumers as co-producers [14]. Examples of such SSTs include multimedia kiosks, express order terminals and self-service kiosks within retail [17, 31]. Self-service checkouts (SSCOs) within supermarkets (see Fig. 1) typically involve a customer scanning or weighing their selected items, bagging them and paying for them, without the assistance of a store employee. Supermarkets within the UK tend to have designated areas for self-service terminals, usually within close proximity to the store exit, containing between 4 and 10 self-service terminals and one member of staff supervising them. In the following sections we briefly review the role of SST use, followed by a discussion of the role of social presence in technology and a brief review of theories of dishonest behavior, before describing our study.

1.1 Retailers and Consumers

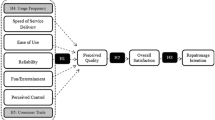

Kallweit et al. [17] investigated why customers choose to use SSTs within retail, focusing on the technology acceptance model (TAM) [10]. An essential component of TAM is the notion that the perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use influences customer decisions to use technology, which, in the case of SST, is associated with perceived service quality. The perceived likelihood of requiring assistance in the absence of staff is a critical variable influencing perceived service quality and has an effect on customer attitudes towards using or the intention to use SST. Convenience perceptions, defined as the perceived time and effort to complete a transaction, are the strongest influence on the potential use for users and non-users of SSTs according to Collier and Kimes [8]. If customers’ perceptions and expectations are not met when using SST then they will be less likely to use them in the future [8]. This theory is consistent with the Resource Matching Perspective, which suggests the expected resources needed to complete a transaction must be met during execution in order for the behavior to reoccur [1, 8]. As customer benefits are crucial to technology acceptance [17, 19], it is important for retailers to promote the convenience that the SSTs can provide, which may include quicker transactions with easy to use interfaces that employ well-known control elements and gestures.

While many studies have focused on the identification of factors that influence consumers’ use of SSTs, such as convenience, ease of use and satisfaction [8, 21], there is a dearth of research on the perceptions of employees who work with the SST. Pietro, Pantano and Virgillo [27] noted that employees and consumers are the effective users of SSTs, thus, it is important for research to consider both perspectives. Using a qualitative approach, Pietro et al. [27] investigated employees’ views on the use of self-service technology; self-service checkouts (SSCOs) were reported to have resulted in an increased number of sales, and do a faster job than the traditional checkout, which enhances the service for the customer. Staff also reported enjoyment with increasing their knowledge and personal skills associated with the use of the technology, resulting in better support of customers in their interactions, which in turn provides benefits for the quality of the final service. This is also consistent with the work by Meuter [22, 23] who described staff’s personal growth in their abilities as intrinsic motivation, resulting from the use of SST. Interacting with customers at self-service checkouts is a good way of maintaining the personal interaction that was a fundamental part of the traditional sales clerk role. However, if self-service checkouts are busy, then this might affect how employees can interact with customers. This may result in reduced customer service and/or reduced level of social presence – a variable which may influence customer behavior at self-service checkouts.

1.2 Social Presence

Social presence is a sense of being with another [7] and creates the illusion in the mind of the perceiver that another intelligence, be it human or artificial, exists within the environment [30]. A review of the research literature suggests that the presence (real or imagined) of others could elicit thoughts that one is being evaluated [24]. Bateson, Nettle and Roberts [2] explored the effects of social presence on behavior by alternating a picture next to an honesty box in which office staff placed money for tea and coffee. In the high social presence condition there was an image of a pair of eyes presented next to the box; in the low social presence condition, an image of a bunch of flowers was shown next to the box. High social presence induced people to behave less dishonest compared to the low social presence condition: there was three times more money in the box when the poster with the eyes was shown compared to when the poster of a bunch of flowers was shown next to the box. Thus, even a perceived social presence in the form of eyes on a poster is sufficient to modify dis/honest behavior and it is reasonable to suggest that this effect might transfer to interaction with technology, as people treat computers as social actors [29], i.e., as if it were human. The perception of social presence can enhance human computer interaction and is especially important for technology that is designed to have limited human contact, while still maintaining a high standard of customer service [18]. The quality of quasi-social interactions is often measured in terms of perceived social presence, which may modify an individual’s behavior [33] to, for example, communicate a positive self-impression [3]. Thus, customer perceptions of social presence may be a useful way for reducing potential dishonest behaviors occurring at SST.

1.3 Dishonest Behavior

Goodenough and Decker [12] discuss theories behind what makes good people steal with respect to the nature/nurture debate. Nature theories suggest people steal as a result of innate motives that encourage them to enhance their property; nurture theories suggest that people learn social behaviors, moral values and laws and it is their learning that influences how they behave. They suggest that emotions, such as empathy, play a part in the consideration of property, as we foresee how we would feel if our property were to be taken from us. Wispé [32] described empathy as “the process whereby one person feels her/himself into the consciousness of another person” (p42). Lower levels of empathy have been linked to an increase in dishonest behaviors such as vandalism and theft [16]. There is a vast amount of research which suggests empathy is an essential component within customer service [20, 26, 28]. However, it is not clear whether the customer experiences empathy when using SST, especially when perceived social presence of the technology (or staff) is low. This may impact on dis/honest behaviors at self-service checkouts.

Harmon-Jones and Mills [13] suggested that creating a sense of personal responsibility results in people modifying their behavior to align with their attitudes. Customers may feel less accountable for dishonest behavior at SSCOs, as they are not interacting with a sales assistant (a social presence), but instead are relying on technology to confirm they have paid for their shopping. Mohr et al. [25] state that there must be a social presence in order for there to be accountability; thus, incorporating a social presence within SST may reduce the likelihood of dishonest behaviors occurring, as social presence may induce similar feelings to those experienced during a typical sales assistant interaction, i.e., personal responsibility for payment.

As part of a wider study into the investigation of dishonest customer behavior, we conducted an exploratory study to assess staff perceptions on social presence, as perceived social presence appears to be a critical factor in customer behavior, which has as yet not been explored in detail at self-service checkouts (SSCOs) typically found in supermarkets. We were particularly interested in how staff perceive their own presence and its effect upon customers, but also how supported staff would feel in their ability to supervise checkouts with the incorporation of an additional social presence, for example, induced by technology. Specifically, the aim of the present study was to investigate the perceived influence of a social presence at self-service checkouts by staff, and its perceived effect on dishonest customer behaviors.

2 Method

An ethnographic approach was adopted involving prolonged immersion within four supermarkets. Semi-structured interviews provided the flexibility of working with the key themes as interviews allowed participants’ insights and attitudes to emerge, allowing for inductive thematic analysis to take place. Interviews with self-service checkout staff explored their views on the effect of actual and perceived social presence on customer behavior. Responses were grouped into two categories, i.e. regarding actual, physical staff presence at self-service and perceived social presence as created by technology, e.g., via cameras. Ad -hoc observations were made to create a fuller picture of behaviors at self-service checkouts.

2.1 Participants

Twenty-six self-service checkout staff, with an age range of 18-63 (8 male, 18 female, with 7 years to 6 months experience in supervising SSCOs) from four supermarkets in the UK were interviewed during June-September 2014.

2.2 Materials and Apparatus

An Olympus VN-713PC Voice Recorder and an Olympus LS-20 M HD Recorder were used to record participants’ responses. A semi-structured interview was used to guide the interview. Verbatim transcription of all interviews was conducted enabling detailed inductive analysis. The supermarkets had designated self-service checkout areas, positioned in a rectangular layout. Two of the supermarkets had six SSCOs and the other two had ten SSCOs.

2.3 Procedure

Ethical Approval was received from Abertay University’s ethics committee. Before conducting the study, store managers from four major supermarkets within the UK were contacted via telephone, to request permission to access their store for the research to take place. Several meetings took place with various members of staff including personnel, managers and supervisors in order to explain what the research was about and permission to interview self-service checkout staff was granted. In the actual interviews, participating staff were also given the opportunity to pose questions to the researcher to explore the context of the study. All volunteering participating staff were asked to read and complete the information and informed consent forms before being interviewed. Participants were initially asked about general customer behaviors at self-service checkouts for example, “What are the most common mistakes made by customers at self-service checkouts” or “Do you feel self-service checkouts have affected customers at all”? Specific questions on dishonest behavior were then asked such as “Have you noticed whether or not people steal at SSCOs?” and “Do you feel various factors affect the likelihood of thefts occurring at SSCOs?”. Interviews took place in staff rooms, medical rooms, store cafes, and customer service desks or areas within their works premises in-line with the ethnographic approach, collecting data within the setting of our group of participants. Interviews were paused if customers approached the area where the staff member was being interviewed. Participants were debriefed at the end of the interview. With the permission of participants, interviews were recorded; a typical interview lasted about 20 min.

3 Results

The findings are described in relation to actual (physical) and perceived social presence in relation to dishonest customer behavior. The findings for generic questions relating to customer behavior at self-service are to be reported elsewhere. For each category, the relevant questions are listed in the graphs with frequencies of mentions by staff and shop.

3.1 Physical Social Presence

Figure 2A shows responses to the question “Have you noticed whether people steal at self-service checkouts?”. The majority of the staff had noticed people stealing even when there is an actual social presence of the staff member. Most staff spontaneously added that busyness at SSCOs is one major component for the likelihood of thefts occurring. Typical comments were that staff are “too busy watching other checkouts” (male, 25), and that it was “too hard for one person to watch all self-service checkouts when it is busy” (female, 52). Another participant stated “only one member of staff present at the self-service checkout, it can be hectic and can affect theft because you can only look after 2 at most” (male, 65). This indicates that staff feel the task attention demanding, and are aware of the gap in customer supervision – or lack of social presence - related to the likelihood of thefts occurring.

When asked “Do you feel various factors affect the likelihood of thefts occurring at self-service checkouts?”, the majority of responses reflected busyness as the most critical factor (Fig. 2B), consistent with the answers to the previous questions. All staff interviewed said that it was “easier for customers to steal when the shop is busy” even when there was an actual social presence and most stated that “more thefts occur when it is busy”. It was suggested that it is “too hard for one person to watch all of the self-service checkouts when it is busy” (male, 23). Staff also reported feeling pressured when the SSCOs are busy as their attention is engaged elsewhere, for example, when helping an individual customer, thus, they are unable to watch for potential thefts occurring and this “creates opportunity for theft” (female, 22).

We also wanted to explore the observed methods customers applied to steal items at self-service (Fig. 2C). While most of the listed methods clearly indicate customer intent to be dishonest, the last method “usually innocent”, points to thefts occurring without intent from the customer. Figure 2C shows that the most common reported method of stealing was customers walking away without paying for their items. It was reported that many of the customers walking away without paying have initially put their payment card in the card terminal within the SSCO, either in an attempt to pay or to deceive the staff member into thinking they were paying. Staff reported being distracted by other customers and state that it is “impossible to watch them all at the same time” (male, 45). The second most common method of theft reported by staff was customers scanning cheap items but bagging expensive items in their place. Customers were reported to be scanning items really fast in attempt to steal items so that their weights would not be detected. Customers also put reduced stickers from one item onto a more expensive item that has not been reduced.

Staff also reported that some innocent mistakes were made by customers in relation to weighing products at SSCOs; for example, one comment was that stealing was committed “not on purpose - it was caused by weight issues” (female, 24).

To summarize, three major components are reflected in the data: staff perceive most but not all customer thefts as intentional, even in the actual presence of staff; staff are aware that attending many customers imposes attentional limitations on their ability to meet the supervisory or customer assistance demands, due to a lack of social presence; and finally, staff perceive a grey area where customers are not intentionally stealing; instead their behaviors are explained as being a result of the SSCO’s technological setup.

It could be suggested, that identified attempts to steal items with intent suggests that customers do not feel they will be accountable, which is consistent with the various theories [11, 25] on the occurrence of dishonest behavior that explain thefts, not only at SSCO, but also during traditional sales interactions [16]. It is noteworthy that staff acutely perceive that their actual presence is insufficient to deter thefts.

Staff were also asked “Do you feel you can tell when someone is going to steal at a self-service checkout?”. This highlighted some behaviors shown by customers which staff associate with an increased likelihood of thefts occurring. For example, some staff members reported certain customers’ “body language is an indicator”, as people can “become shifty, looking around the SSCOs” (female, 26). Some staff members stated that if a customer were to go to the furthest checkout away from the staff member that it would make them more aware of that customer’s behavior, and more likely to keep a closer eye on them. Customers who state that they no longer want an item after there has been a weight issue, due to an item not being scanned properly and then bagged, were reported by staff to have been likely to have been trying to act dishonestly. Staff reported that they can ask to check customers’ shopping bags if they suspect dishonest behavior, however, if the customer has not left the shop with an unpaid item then it is not considered to be theft and they cannot be prosecuted without clear evidence of an intent to behave dishonestly.

3.2 Perceived Social Presence

In order to gauge how staff would assess the effect of a perceived social presence on customers they were initially asked “Do you feel that if customers felt they were being watched it would have any effect on the likelihood of thefts occurring?” (Fig. 3A).

The majority of staff reported that this might reduce thefts. More specifically, staff reported that if customers felt they were being watched then it would reduce thefts occurring as they would feel “less likely to get away with it” (female, 46) or “would feel paranoid they will get caught” (female, 26). This suggests that staff perceive customers’ perceptions of being watched can modify behavior to reduce the likelihood of thefts occurring, and raises questions as to how this social presence can be induced – either by the presence of more staff, or via technological implementations.

To explore the latter, staff were asked “Do you feel that an onscreen camera showing what was being scanned and bagged would have any effect on the likelihood of thefts occurring?” (Fig. 3B). The majority of staff reported that they felt an onscreen camera would reduce thefts at SSCOs, which was illustrated by the comment that “if customers could see it and were more aware they were being watched it definitely would reduce thefts” (male, 53).

To summarize, there were two major components reflected in the data: staff believe that the general perception of being watched (social presence) can modify behavior to reduce the likelihood of thefts occurring; staff also perceived a potential for the technological implementation of social presence at SSCO to be helpful, for example, via an onscreen camera.

4 Discussion

Although there is always an actual social presence with a member of staff at SSCOs, the present study found that staff perceive themselves to be limited in their capacity to create the same sense of social presence when SSCOs are busy, which they perceive leads to a greater risk of thefts occurring. Staff also reported feeling under pressure when self-service checkouts are busy as they are impaired in their ability to watch for thefts and customer problems occurring, and maintain a high level of social presence at the same time, assisting customers. Pietro et al.’s [27] study found staff reporting feeling more satisfied at work when working with SSCOs as they could provide a “better” final service. This may not be possible if staff are feeling pressured due to the perceived high risk of thefts at SSCOs when they are busy. Implementing a social presence within a self-service interface may increase the sense of social presence but also maintain a high level of customer service, as the customers can feel supported throughout their transaction by it providing the impression that help is at hand. This may also enhance the likelihood of staff feeling satisfied with their work and increase levels of employee job performance, as they may feel supported in giving assistance to customers.

Most staff agreed that theft would be reduced if customers felt they were being watched generally. This is consistent with Baumeister’s [3] theory which stated feeling the presence of others can lead individuals to alter their behavior in a manner that communicates a positive self-impression. This view was underlined when the majority of staff agreed that an onscreen camera on SSCOs would reduce the likelihood of theft. Thus, staff perceive that they could be assisted by a social presence implemented in technology. It is noteworthy that a social presence may be created via CCTV in stores and, thus, should already be perceived by customers. However, only two members of staff made references to CCTV in relation to the question “Do you feel that if customers felt they were being watched it would have any effect on the likelihood of theft occurring?”, although all participating stores in this study used CCTV supervision. This suggests that most staff do not perceive CCTV to induce an effective social presence on customers. There is considerable research to suggest that CCTV has become over-familiar to customers and that it no longer upholds its crime reduction effects [4, 15]. An onscreen camera at self-service checkouts may be a more effective way of reminding people that they are under direct, i.e., one-to-one, surveillance and create an effective sense of social presence to result in less theft occurring.

Within this context it is also important to point out that the perception of one’s own presence can affect behavior. The self-focused attention theory refers to an individual considering their internal standards and making sure their behavior is consistent with these standards [5]. Beaman et al. [5] conducted an experiment on Halloween whilst children were trick-or-treating. Children were asked to take only one sweet and were then left alone with the sweets. Children were significantly more likely to only take one sweet when there was a mirror placed behind the sweet bowl than without the mirror. This suggests that their reflection increased their self-awareness and perhaps sense of social presence, encouraging them to behave in a manner that was consistent with the standards associated with the setting [5]. An onscreen camera at SSCOs displaying the customer’s interaction with the SSCO via its interface may likewise enhance customers’ self-awareness and sense of social presence.

Staff reported that some thefts were actually innocent mistakes made by the customer due to the interactions with the SSCO, mainly weighing items. Genuine mistakes can happen when using SSCOs, perhaps due to lack of experience with the system, thus clear instructions on how to use SSCOs may prevent this from happening. The potential for more challenging transaction processes at SSCOs may be encouraging thefts, however, as the customer can blame any un-scanned items on the technology, masking their intention to steal, and reducing the feeling of responsibility. Frustration may be experienced by the customer if the SSCOs are not operating in a straightforward manner, which may lead to dishonest behavior such as bagging un-scanned items, consistent with the “frustration factor” (p14) stated by Beck [6]. It is reasonable to assume that frustration potentially provides the customer with a reason to justify their dishonest behavior, which Beck [6] defines as the “self-scan defence” (p14). It could be argued that customers who do not pre-plan to act dishonestly at self-service checkouts, but may be influenced by frustration, would be likely to be guided by a social presence, as it would encourage them to behave in a socially accepted manner, reducing the likelihood of thefts [13]. A social presence in the form of an onscreen camera at SSCOs may result in customers feeling accountable for their actions, as social presence induces a sense of accountability [25]. Future research will address the aspects of social presence and possible manifestation in the context of technology.

4.1 Conclusions

The findings from this study suggest that the effect of social presence on customer behaviors deserves more exploration. Actual staff presence should consistently induce a sense of social presence, however, this is not perceived by staff to be sufficient within self-service. The present study found that the presence of numerous customers increases the perceived likelihood of theft. Arguably, it can be suggested that a greater number of staff members would reduce the likelihood of thefts occurring. Therefore, the effects of staff density and perceived identity (staff or customer) within a SSCO area on social presence require to be further investigated. There is also uncertainty as to whether or not customers are intentionally stealing at SSCOs or whether thefts occur due to aspects of the technological setup, providing justification for dishonest behaviors. Future research will elaborate to what extent the perceived social presence via technological systems might support staff in their task and will explore customer views. This may benefit future interactions for the retailer, staff and customers, and encourage businesses to obtain SST to enhance their productive potential.

References

Anand, P., Sternthal, B.: Ease of message processing as a moderator of repetition effects in advertising. J. Mark. Res. 27(3), 345–353 (1990)

Bateson, M., Nettle, D., Roberts, G.: Cues of being watched enhance cooperation in a real-world setting. Biol. Lett. 2, 412–414 (2006)

Baumeister, R.F.: A self-presentational view of social phenomena. Psychol. Bull. 91, 3–26 (1982)

Beck, A., Willis, A.: Context-specific measures of CCTV effectiveness in the retail sector. In: Surveillance of Public Space: CCTV, Street Lighting and Crime Prevention. Crime Prevention Studies Series, pp. 251–269 (1999)

Beaman, A.L., Klentz, B., Diener, E., Svanum, S.: Self-awareness and transgression in children: two field studies. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 37(10), 1835–1846 (1979)

Beck, A.: Self-scan checkouts and retail loss: understanding the risk and minimising the threat. Secur. J. 24(3), 199–215 (2011)

Biocca, F., Harms, C., Burgoon, J.K.: Towards a more robust theory and measure of social presence: review and suggested criteria. Presence: Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 12(5), 456–480 (2003)

Collier, J.E., Kimes, S.E.: Only if it is convenient understanding how convenience influences self-service technology evaluation. J. Serv. Res. 16(1), 39–51 (2013)

Chen, K.J.: Technology-based service and customer satisfaction in developing countries. Int. J. Manag. 22(2), 307–318 (2005)

Davis, F.D.: Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 13(3), 319–340 (1989)

Dooley, J.J., Pyżalski, J., Cross, D.: Cyberbullying versus face-to-face bullying. J. Psychol. 217(4), 182–188 (2009)

Goodenough, O.R., Decker, G.: Why do Good People Steal Intellectual Property? The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection (2008). http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1518952

Harmon-Jones, E., Mills, J.: Cognitive Dissonance: Progress on a Pivotal Theory in Psychology. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC (1999)

Hilton, T., Hughes, T., Little, E., Marandi, E.: Adopting self-service technology to do more with less. J. Serv. Mark. 27(1), 3–12 (2013)

Honess, T., Charman, E.: Closed Circuit Television in Public Places. Home Office, London (1992). (Police Research Group Crime Prevention Unit Series Paper, #35.)

Jolliffe, D., Farrington, D.P.: Examining the relationship between low empathy and self-reported offending. Leg. Criminological Psychol. 12(2), 265–286 (2007)

Kallweit, K., Spreer, P., Toporowski, W.: Why do customers use self-service information technologies in retail? The mediating effect of perceived service quality. J. Consum. Serv. 21, 268–276 (2014)

Kang, M., Gretzel, U.: Differences in social presence perceptions. In: Fuchs, M., Ricci, F., Cantoni, L. (eds.) Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2012, pp. 437–447. Springer, New York (2012)

Kinard, B.R., Capella, M.L., Kinard, J.L.: The impact of social presence on technology based self-service use: the role of familiarity. Serv. Mark. Q. 30(3), 303–314 (2009)

Korczynski, M.: The contradictions of service work: call centre as customer-oriented bureaucracy. In: Customer Service: Empowerment and Entrapment, pp. 79–101 (2001)

Lee, H.J., Yang, K.: Interpersonal service quality, self-service technology (SST) service quality, and retail patronage. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 20(1), 51–57 (2013)

Meuter, M.L., Bitner, M.J., Ostrom, A.L., Brown, S.W.: Choosing among alternative service delivery modes: an investigation of customer trial of self-service technologies. J. Mark. 69(2), 61–83 (2005)

Meuter, M.L., Ostrom, A.L., Roundtree, R.I., Bitner, M.J.: Self-service technologies: understanding customer satisfaction with technology-based service encounters. J. Mark. 64(3), 50–64 (2000)

Miller, R.S., Leary, M.R.: Social Sources and Interactive Functions of Emotion: The Case of Embarrassment (1992)

Mohr, D.C., Cuijpers, P., Lehman, K.: Supportive accountability: a model for providing human support to enhance adherence to ehealth interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 13(1), e30 (2011)

Parasuraman, A., Berry, L.L., Zeithaml, V.A.: Understanding customer expectations of service. Sloan Manag. Rev. 32(3), 39–48 (1991)

Pietro, L., Pantano, E., Virgillo, F.: Frontline employees’ attitudes towards self-service technologies: threats or opportunity for job performance. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 21(5), 844–850 (2014)

Siddiqi, K.O.: Interrelations between service quality attributes, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty in the retail banking sector in bangladesh. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 6(3), p12 (2011)

Reeves, B., Nass, C.: The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media like Real People and Places. Cambridge University Press, New York (1996)

Romano, D.M., Sheppard, G., Hall, J., Miller, A., Ma, Z.: BASIC: A believable, adaptable socially intelligent character for social presence. In: PRESENCE 2005, The 8th Annual International Workshop on Presence, 21–22, September, 2005. University College London, London (2005)

Wang, M.C.H.: Determinants and consequences of consumer satisfaction with self-service technology in a retail setting. Managing Serv. Qual. 22(2), 128–144 (2012)

Wispé, L.: History of the concept of empathy. In: Eisenberg, N., Strayer, J. (eds.) Empathy and its Development, pp. 17–37. Cambridge University Press, New York (1987)

Zhao, S.: Toward a taxonomy of copresence. Presence 12(5), 445–455 (2003)

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the participating supermarkets and their staff for accommodating and agreeing to participate in this research. We would also like to thank NCR for their on-going support with our research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Creighton, S., Johnson, G., Robertson, P., Law, J., Szymkowiak, A. (2015). Dishonest Behavior at Self-Service Checkouts. In: Fui-Hoon Nah, F., Tan, CH. (eds) HCI in Business. HCIB 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 9191. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20895-4_25

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20895-4_25

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-20894-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-20895-4

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)