Abstract

The aim of the paper is to analyze the relationship between educational research and its use in the policy-making process in Romania. We examine the ways in which research influences educational policy, the mechanisms by which this influence operates and whether it can be improved. We focus firstly upon research production, looking to identify the researchers’ perception regarding the quality and the potential of their research with respect to the policy-making process. Secondly, we analyze policy makers’ opinions regarding research and its incorporation into policy-making. Finally, we discuss the obstacles and opportunities presented by the transfer of research into policy making, and make some suggestions as to how this can be improved. We used qualitative methods based on in-depth interviews with researchers and policy-makers in Romania. The results show that, in general, policy makers are not using research results, and we identify the causes of this situation. We identify different types of causes, from the quality and visibility of research activity to the structural and institutional obstacles which research activity and transfer have to face. The implications are discussed at three different levels: the micro level represented by the individual researcher, the mezzo level, represented by the organization and the macro level – the systemic context. The conclusions offer researchers and policy-makers opportunities to consider opportunities and constraints, in order to improve the relationship between the educational research and its potential users.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Over the last few years, there has been an increase in interest in European countries in the issue of how evidence is used to inform educational policy, and how these processes might be improved. Evidence informed policy and practice in education is one of the immediate priorities of the European Commission as described in, for example, the ET2020 strategic framework (European Commission 2009).

A growing interest in strengthening the link between research and educational policymaking has been reported in a number of European countries. There is evidence, for example, that in Denmark research has become more widely used in deciding policy (Bugge Bertramsen 2007). In the Netherlands, evidence-based strategies are present in the national policy agenda, and a new unit within the Ministry of Education Culture and Science, called the “Knowledge Chamber” (Kenniskamer), has been created with the aim of producing properly researched information which can be used by policy makers (Stegeman 2007), while in Finland the role of evaluation has assumed a greater importance within public administration (Jakku-Sihvonen 2007).

However, there is still a clear perception that in the field of education and research the evidence base for policies is much less substantial than for other areas covered by the Lisbon Strategy, such as economic growth (GDP) or the labour market (employment). It has been observed that, in contrast with technological or medical research, in education research there is a low level of R&D expenditure and success in knowledge production, and a correspondingly slow rate in the dissemination and implementation of research (European Commission 2007).

Most of the attention in the literature on the impact of research for policymaking focuses on research production. The research will not impact useless users are willing and able to benefit from its findings. The capacity of users is therefore a significant, but largely uninvestigated issue (Lavis et al. 2003).

The potential range of people and organizations interested in research in education is wide. They include all the teachers, students, administrators and policy-makers who are directly involved in education and governments as key bodies responsible for the educational system. Beyond that, almost every group in society—parents, employers, workers and their organizations, and the non-profit sector—has an interest in education in one way or another and thus, stands to benefit from research (Levin 2004).

A number of issues have been identified, concerning the limited impact of the knowledge produced by educational research:

-

Relevance and quality. Recent writing on educational research has argued that short-term, small-scale “consultancy-style” funding and the “turbulence” of higher education and higher education policy encourage “reductionist, even myopic, research into higher education” (Scott 2000). Higher education research is thus regarded as “weakly institutionalized” (Scott 2000) and as lacking “stability and quality” (Teichler 2000). As Locke (2009) has put it, ‘On the one hand, efforts to make higher education research more relevant to decision-makers may render it less rigorous in the eyes of academic peers, and therefore even less likely to result in publication in prestigious journals. On the other, attempts to build a firmer intellectual foundation, a more critical and sharper analytical edge and a stronger institutional base within higher education itself, all risk eroding its influence on national policy making and institutional practice.’ (Locke 2009).

-

Lower levels of education research funding compared to other policy fields (OECD 2000, 2003).

-

Diversity of educational research and researchers. As a field of enquiry rather than a discipline in its own right, ‘educational research relies on different disciplines and therefore may follow very different methodologies to reach different or even contradictory results on the same issues’ (European Commission 2007: 15).

Difficulties in the process of knowledge transfer from research into policy are not unique to education. A recent report from the MASIS project (Monitoring Policy and Research Activities on Science in Society in Europe) on the knowledge transfer between research and policy in fields other than education suggest that a number of structural, contextual and cultural circumstances play a key role.

However, many of the challenges for research-policy transfer relate to the communication mechanisms and practices used (Bultitude et al. 2012; Cherney et al. 2012). Studies in educational research and practice indicate that policy-makers often perceive the use of technical and complex language in research reports as barriers (Vanderlinde and Van Braaka 2010). As has emerged in a series of interviews and surveys undertaken in 2008 by EC-DG Research with European policymakers, senior advisers and knowledge transfer specialists, among the main factors hindering the take-up of research-based evidence by policy-makers reported by the three groups are differing time scales and imperatives for communication between policy-makers and researchers, the absence of appropriate channels for communicating between both groups and filters for translating results (European Commission 2008).

These remarks essentially point towards the process linking research findings to educational policy-making, and indicate the need to re-examine the role of the networks connecting educational research and decision-making (Levin 2004; Saunders 2007; Sebba 2007).

OECD has coined the term “brokerage” to define “the processes by which information is mediated between stakeholders”; the processes include formal and informal mechanisms, and, in some instances, agencies specifically set up to carry out this function. The 2007 EC Staff Working Document employs the term “knowledge mediation” as synonym of “brokerage”, defined as ‘the translation and the dissemination of knowledge and findings of research so that they can inform and influence the policymaking dimension’ (European Commission 2007: 6). Mediation can take an “active” or an “interactive form”, providing resources directly accessible to decision-makers (e.g. databases and websites) or mechanisms that actively engage the decision makers in the process, for example through forms of partnership (European Commission 2007: 42).

The dimension of “knowledge mediation” or “brokerage” for educational research has been flagged up by both EC and OECD as the weakest link in the research-policy transfer.

According to a survey conducted by the EIPEE project (Evidence-informed Policy-making in Education in Europe) in 2011, of 269 identified examples of linking activities in education in 30 of the 32 target countries in Europe, only 10 % of the activities identified occurred at the mediation level, compared with 67 % predominantly concerned with producing research (Gough et al. 2011).

In most Member States, web portals, databases and conferences exist to act as a communication channel between research results and policy-makers. These instruments are usually the responsibility of public education authorities or research institutions. The EC experts, however, are still waiting for conclusions about their actual dissemination and therefore their relevance and usefulness (European Commission 2007: 46).

A number of countries are seeking to achieve a closer and more stable relationship between research and policy through new forms of partnership between the communities. Some Member States have created regional institutions to create a consensual approach to policy development at local level (e.g. DE, ES, FR, IT). Brokerage agencies have been established in Denmark, Netherlands and United Kingdom with the aim of providing independent reviews, creating agreed methods of evaluation, and presenting the research results in ways which fit better with the needs of end-users. New research/analysis units have been developed within education ministries in, for example, Malta, the Netherlands, Spain, France, and the UK, and ‘policy-facing research centres’ in Finland, Austria, and Denmark (European Commission 2007: 46–51).

Furthermore, the correlation between the presence of brokerage arrangements and the extent to which research-based knowledge has a real impact on decision-making is found to be particularly weak in Romania and Albania. Though brokerage arrangements are in place, the de facto impact of the scientific evidence on decision-making processes appears to be modest (MASIS 2012). In Romania, implementation and regulation mechanisms have not led to planned, systematic and predictable outcomes in the long run. For example the problems within Romanian scientific research have been addressed in numerous articles, many of them appearing in the Science Policy Review. Kappel and Ignat (2012) claim that, in Romania, research faces particular difficulties.

-

In Romania, both theoretical and applied research do not engage in dialogue with each other. Rather, they are based on flows of communication, information or knowledge that takes the form of a vertical transfer from science to technology.

-

There is no need to examine the process of technological transfer;

-

Issues about the quality of applied research are still unaddressed in Romania, and aspects of research relating to design and micro- production are not financed by the state.

Moreover, Lupei (2012) identifies further problems in the field of Romanian research: “In spite of some positive aspects, such as the elaboration of Romanian research strategy in line with the European Union framework and national research-development plans, the outcomes are below expectations”.

Although it ranks very low, research results have improved in the last 5–6 years. There has been a growth in investment in infrastructure and an increase in the number of publications and patents (although it is still small compared to other former socialist countries).

The aim of this paper is to identify the major issues linked to the use of educational research, and the relationship between research in education and education policy insofar as they emerge through the attitudes and preoccupations of education researchers and policy makers. Does research influence educational policy? In what way? How well? In order to answer these questions, we focus first on research production, trying to identify the researchers’ perception about the quality and the potential of their research for the policy making process. Secondly, we analyze the policy makers’ attitudes towards research products and transfer. Finally, we discuss the obstacles and opportunities of research transfer to policy making, and offer some suggestions as to how it can be improved.

2 Methods

A qualitative approach, through the use of in-depth interviews, was adopted (Denzin and Lincoln 2005). The interview guideline was validated by pilot testing, evaluation and consultation with senior professional colleagues.

2.1 Method and Instrument

The use of interviews meant that data could be collected directly from the key figures within the university and policy making field. The interviews were conducted over a period of 6 months with the questions being determined by the nature of the research objectives and the theoretical framework identified in the introduction.

Internal validity was ensured by the selection of informants using the following criteria: length of experience in their position, type of institutional body (individual or collective), training and academic standing. This ensured that our interviewees conformed to a wide variety of profiles. The interviews took between 40 and 50 min and were conducted at each participant’s workplace. The selection of the respondent sample was based on their representativeness, established using non-probability criteria and using the theoretical sampling of Flick (2004). In order to act as a control on the consistency of the responses, 6 of the participants were interviewed a second time.

The present study used interviews organized with two different key figures involved in the process of disseminating educational research results for policy-making: decision-makers and researchers. For decision-makers, a semi-structured interview was employed. The participants were asked about the following topics:

-

their perceptions of the impact of educational research in the interviewees’ department or institution in the last 2–3 years

-

their perceptions about the areas in which recently performed research was most widely used

-

their opinion regarding factors that favour/inhibit the use of research in decision making.

Data from researchers were collected through structured interviews that included open-ended questions. The questions examined the functioning of the research system in Romania, the characteristics of research production, research dissemination, obstacles and opportunities regarding research in education, and its transfer into the policy making sphere. The questions also focused on the involvement of key social groups and the structures and processes which serve to enhance the use of the research results in education.

2.2 Participants

Interviews were conducted at four public universities in Romania: University of Bucharest (UB), Alexandru Ioan Cuza University in Iasi (UAIC), the Babes Bolyai University of Cluj (UBB) and Transylvania University of Brasov (UTB). These are ones of the most important universities across Romania, according to the classification of the universities in the Romanian higher education system.Footnote 1 UB, UAIC and UBB are the first three universities according to “the advanced research and teaching” classification and UTB is the first one according to the “research and teaching based universities” classification.

We also interviewed key figures involved into policy making from the national educational agencies and the Ministry of Education. The participants were:

-

1.

Academics performing research and engaged in decision-making in universities, departments or faculties. This category comprised in-depth interviews with university vice-rectors in charge of quality assurance, faculty deans and heads of departments.

-

2.

Leading analysts of higher education governance and management. This comprised interviews with senior academics and experts in higher education management, as well as academics currently engaged in senior managerial roles, such as chancellor or vice-chancellor.

-

3.

Researchers. In this category we interviewed researchers working at university level and at research centres’ level. The participants’ profiles are detailed in Table 1.

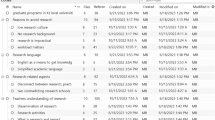

Table 1 Participants’ description

2.3 Data Analysis

Data from the interviews were analyzed and systematized using Maxqda 11 software. A preliminary report was drafted, identifying the key themes that emerged from the interviews, as well as any issues or themes that could be considered contentious. This report then formed the basis for the second phase of data collection, involving a group of nine academics. These participants were selected on the basis of their expertise in management in the context of higher education in Europe.

The data analysis was conducted on three levels. At the preliminary level the key units of meaning were identified. The second level of analysis involved the identification of single units of meaning through an axial coding system linking the dimensions of analysis with a set of complex significance topics. The third level of analysis extended the process of synthesis in order to extract the textual units.

The strategy used to ensure internal validity was the selection of informants using a criteria system incorporating such aspects as: experience in management positions, type of institution (individual or collective), training, academic standing, and so on. This ensured that there was variety in our informants’ profiles.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 The Research in Higher Education in Romania

Over the past few years, the Romanian Higher Education System has developed an interest in scientific research, covering all fields of study, except educational practices and policies. Both researchers and policy-makers welcome the recent governmental focus on financing research activity, as well as on upgrading it to a high standard so as to gain a high position in the academic rankings of world universities. The impetus for this derives from the most recent assessment of Romanian universities, an important criterion being the quality of the scientific outcomes.

In an attempt to define the context of research in Romania, participants showed an interest in the issue and identified the factors preventing the efficient production and transfer of research. Insufficient financing and low quality research evaluation criteria are offered as possible causes.

A key observation is the growing interest in research shown by those willing to take part in this kind of activity: There is a favourable context for research in Romania and, like any crisis situation, it fosters innovation. On the contrary, as far as financing is concerned, research activity must be reconsidered to be the backbone of any developing university. For the past year and a half, I have noticed a real interest in research on the part of academics and teaching staff preparing for their teaching grade I.” (I6)

In spite of this favourable period, research activity faces structural and organizational difficulties. For instance, one of the researchers, a vice-rector, declared: At the moment, in Romania, research is struggling. There are numerous legal and administrative barriers within the institution. People are extraordinary, but they are not given enough freedom to exercise their initiative. (I8)

The questions to be posed are what are the causes leading to such a situation, and what can be done to improve the links between scientific research and decision-making processes in education? To answer these questions, we identify aspects of academic research and the transfer strategies used.

3.2 Research Production

One aspect of the research transfer process is research production and its producers. It should be stressed that the results of research must be transferred to policies based on high quality research.

3.2.1 Scientific Research—Between Relevance and Stringency

Most of the participants in the survey define the current context of the research production within the universities as being segmented and ambiguous, incoherent and fragmented. This is mainly due to the wide range of objectives and to the gap between research and politics. With regard to the first point, the target group believes that: I would stress the idea that in Romania, researchers adopt European, rather than national policy determinants. (I1)

Likewise, research production is not based on the real needs of the system or local context, but rather on international priorities, or they are imposed by the national or European financing organizations. In this sense: Research should be based on the researcher’s thirst for knowledge. It seems to me that, nowadays, researchers proceed according to financial and research opportunities. (I10)

Furthermore, researchers believe that research activity is less institutionalized and lacks sustainability and quality as a result of a lack of financial resources. Thus, the interviewees consider that: There is little to complain about it. There should be loud voices, more focused, less divergent. The existence of a scientific community becomes a “must”, a community bound together by adults’ training and education and prepared to speak up for educational policies. (I11)

Apart from this, there are also structural and organizational drawbacks hampering the management of research and highlighting the financial difficulties: First, it is the research budget and reductions, and this is always tough for the university budget. In the case of LLL projects, based on a fixed budget, Romanian legislation prevented some activities from being carried out. Even if money is not a problem, the parameters of Romanian legislation and some exaggerated interpretations make it difficult for research activities to be performed. Moreover, there has been a reduction in finance at the European level for some time now. (I8)

Besides, university managers believe that, even if it has become a priority, scientific research is still an unequal structured and disorganized domain. Research is part of any academic field of activity. In the field of research, however, there is little research, besides the scarcity of financial resources. (I12)

Another limit on research development is incoherent management (characterized by the lack of coherent politics and strategies promoted from top management), and a poorly developed culture of research (“poor interest in research”, “the value given to the research activity in the academic life” among others factors, as participants stated). From a structural point of view, I believe that organizational culture plays a vital role. Any organization is represented by the culture it promotes. (I3)

3.2.2 Research Activity Between Duty and Vocation

Various answers helped to sketch the profile of the researcher, as the centre of any research activity. On the one hand, universities and public organizations expect researchers to produce high quality knowledge likely to have social application and, on the other hand, their activity is deterred by cumbersome institutional mechanisms and the lack of resources, and the balance between research and teaching in the case of academics in universities. Actually, researchers tend to focus more on the importance of research than on teaching. Illustrative of this is the comment: Research is moving towards an international standard. Most universities exert a lot of pressure on the teaching staff to carry out research. Eight years ago, the focus was on teaching. Academic management considers research to be a prospective source of finance. This trend can now be found in the Romanian education system. The pressure is even greater due to academic ranking. (I11)

In order to survive, as a researcher, you need to be “strategic”, “goal-oriented so as to meet the social and academic demands regarding current interdisciplinary approaches promoted by the national and international research strategies” as argues one of the researchers.

The pressure to publish and the amount of research-teaching activity detract researchers’ attention from the business of applying research results to educational policies. In this sense: First, research only meant public dissemination at a conference and publication of one article, no more. Now, things have changed. We must publish only ISI articles. (I4)

The teaching-research relationship is frequently raised by the interviewees, who mainly emphasized the value of research for institutional accreditation and personal assessment. Another key observation is the teaching workload that will influence the scientific profile of the research in education: Most people in education are overloaded with tasks other than research. The regular teaching workload does not include time for research activities. Obviously, the amount you can produce is insignificant. There is not enough time for research. Cross-disciplinary teams are required. I hope there will be sufficient time and resources to motivate people. (I10)

The evaluation system of the teaching personnel prioritizes research activity. Nevertheless, it brings about a conflict of roles at a personal level and causes frustration since your job is purely didactic, whereas your evaluation is based on research. The teaching workload is too high, and the effort expended on daily tasks leaves little time for research (I3).

All in all, the research system needs to be improved from the very beginning, starting with its production stages. All the participants in the research agreed on this. Other possible solutions are the balancing of teaching and research activities, and generating high motivation for the latter, as well as taking into account the impact that scientific research must have on the local educational practices.

3.3 Research Activity Between Duty and Vocation

Frameworks and policies developed by education systems have a great influence on schools. Despite the general move towards greater school-level responsibility over the past 15 years, it is still the case in government school systems that central policy makers have a significant influence on school staffing and resourcing, curriculum development, assessment, and shaping the environment within which schools operate. Central government educational policies also influence the conduct of schools and the work of teachers in other ways. The most obvious is through resource allocation in terms of staffing, and the provision of discretionary funding.

Research therefore can have an impact on schools not only through the direct take-up of new ideas and findings by principals and teachers, but also through developments initiated by government educational policy makers that are derived from research, and through information that is disseminated to schools by the central government.

Both researchers and decision-makers agree on the relationship between research and education, claiming there is no systematic transfer of research results to education. Researchers do not consider the transfer of research a priority, as within the field of education there is a general conservativism and a reluctance to change (I8). Lack of interest in research transfer is also due to lack of financing for the dissemination of project outcomes.

Bureaucracy is one of the main obstacles faced by researchers with regard to research transfer, as well as the lack of specialized academic structures likely to ensure the effectiveness of the process (I3).

Another reason is the researchers’ “laziness”. According to a researcher’s opinion: “One cause is laziness. People tend to feel more comfortable with what they already know. Obviously, there is some reluctance to undertake a research program, so much so financing is uncertain. You can launch a research project only to end up empty handed, with the project being suspended” (10)

There are also barriers at the level of organizations and structures in charge of implementing the outcomes of research programmes, such as the Ministry of Education. Researchers consider it may not be interested enough in the research results and the participants emphasize the reasons why:

Another problem is the frequent and rapid changes taking place within the Ministry. One politician may adopt a particular measure and then he/she leaves and somebody else steps in and no longer wants to implement it. Thus, there is change for the sake of change. There is no consistency and continuity in decision-making. For example, the Baccalaureate exam and admission to the pre first grade program. (I9)

Nevertheless, most of the limits of research transfer deal with the language barriers between the two sectors or limits of discourse reception, which, sometimes, can be too technical or scientific. The causes of such difficulties in the discourse between the two educational sectors, as well as the possible impact on educational practices are discussed below: There is also a language and motivation problem. Some research results do not need to be interpreted by the decision-maker before reaching the practitioner. For instance, methodologically speaking, some results may not need validation by a decision-maker so as to be implemented by a practitioner. However, when these results are presented in difficult or incomprehensible language, the practitioner will always be reluctant to adopt them. (I3)

The researcher plays a crucial role in this process; it is up to him/her to adapt the whole process and communication strategies to the needs of the beneficiary:

I may be suspected of using too much theory. Nevertheless, I have learned to identify and shape my own audience as a researcher, so that, the moment I design and plan the research activity, I keep in constant contact with my prospective beneficiaries. [..]I have done this and I know it is possible. When I claimed there were no results regarding the subject the decision maker was interested in, within very short time and with no institutional support, I managed to convince him/her not to make a decision. I think this shows how it should be. (I5)

Success in communication is due to the decision-makers’ responsiveness and willingness to trust the experts: To be responsive to a certain category of people. Not all results are research results. (I3)

Research is disseminated through various channels and the language is extremely important: All persons are affected by this educational activity. Hence, you must pay attention to the language you use, to the communication channels, the instruments meant to bring about change, that’s why research in education is so difficult. It is very easy to gather data. However, it becomes difficult to carry out research in order to make a change. (I4)

With regard to the means of research transfer in education, the respondents were of the opinion that the best strategy to merge research with the decision-making process is the creation of collaboration networks between researchers and decision-makers, the dissemination of research to educational institutions, as well as the publication of articles.

While these conditions are essential to ensure the wide influence of research, they must be supported by ease of access to research findings. This ease of access depends on the active dissemination of research findings, but also depends on the form this takes. A range of suggestions to improve research dissemination arises from this project. Most of these are based on the view that the dissemination of research findings should be an integral part of the research process for all researchers, including postgraduate students. Such dissemination, while including publication in academic journals, should take a wider range of forms. Generally, single studies do not have a significant impact. Literature reviews, and papers that synthesize research in a form that is accessible to decision-makers are needed. Programmes and applications based on research are a means of actively involving both researcher and decision-makers together.

4 Discussion

The results of the research have emphasized the links between education and the decision-making process in the field of education. The aim was to characterize the two contexts and identify the corresponding elements of continuity or discontinuity.

The results of the study show a disconnection between the researchers’ and decision-makers’ expectations. The researchers require more attention from the decision makers and expect to be involved directly in the decision making process. This is due to a lack of quality caused by the poor research culture within higher education, as well as by lack of a systematic approach in disseminating research results (Simon 2012). First, participants in the present research highlighted the importance of financing as a key element in producing good quality results and in being able to produce sufficient research. The issue of financing is not typical of the Romanian context. The financing bodies in Romania either fail to provide the necessary budget for the research activity (Ion and Iucu 2012; Simon 2012), or do not use solid and transparent assessment criteria when considering the results of the research (Kappel and Ignat 2012).

Secondly, the results of our research underline the fact that research carried out within universities is inadequate to meet the needs of the decision makers, as shown by Scott as early as 2000, taking into account both research production, and research use in policy making. This leads to at least two opposite positions in higher education. One is related to the research environment with implication on the research production and supported by leading researchers, with implications for academic management and for teaching and research balance in higher education. The other addresses the decision-makers environment with reference to the research use and claims that scientific research is capable of “meeting” the political objectives, with implications for financing and control.

The present research identifies some of the causes of the gap between the research and decision-making process. Some of these causes are related to the production of research and draw attention to the fact that the results do not always meet the needs of society. First of all, researchers consider that their research activity is influenced by the priorities of the financial bodies and claims for a real relationship between research results and political trends in order to create the necessary conditions for the transfer of results to policy. They have low expectations of the contribution of research to the decision-making process and regarding the quality of their studies. For this reason, our research is in line with the studies carried out in Australia by Smith (2000), who claims that research is just one of the information sources and not the only one. Likewise, the results of the current research agree with the studies done by Kappel and Ignat (2012) who claim that one of the causes of inefficient implementation of research in Romania is the small number of applied research studies and Romanian researchers’ mentality, namely, an unwillingness to accept internationally accepted quality criteria.

Another barrier to research transfer is the procedure. As argued by Scott (2000), research projects, due to their long time scale, fail to address promptly political issues that require swift solutions. Hence, Huberman (1990) claims that the interaction between the two domains brings about areas of collaboration between research results and political issues. Moreover, these links may be facilitated by the institutional structures of the parties involved (Selby-Smith et al. 1992).

In addition, the present study sheds light upon the issue of language incompatibility. Most of the research results focus on dissemination and the transfer of research. The literature in the field highlights the need for harmonization of the two contexts, in so far as language is concerned. Both researchers and decision makers live in separate worlds, observe different norms and speak different languages (Ungerleider 2012). Our study shows that the “laws” governing research activity and decision making processes are different (Levin 2004), and focuses on the importance of mediation between the two domains. According to Huberman (1990), there is a need for ‘sustained interactivity’, through which we can generate changes, data flows and stimulate research competencies.

National studies carried out by authorized and accredited bodies showed that universities failed to plan their institutional mission in accordance with the professional roles and structures of staff. It may be possible that a higher education institution, whose mission is to focus on its educational objectives, may fail to fulfil its national mission, and thus have negative effects on the whole system. The relationship between quality assurance and research production cannot be ignored, so much so that just one university in Romania is responsible for almost 10 % of the entire scientific research output. Accuracy and seriousness in the reporting of scientific data is one of the most significant proposals for the improvement of national policies.

5 Conclusions

Considering the participants’ opinion, we provide some guidelines for researchers and policy-makers in the field of education. These tentative guidelines are illustrated according to three levels:

5.1 At the Micro or Researcher’s Level

The results of our research may have implications for various levels. Firstly, researchers’ responsibilities for research production and transfer are highlighted. As professionals, researchers must provide good results and contribute to the development of improved performance in education. Another key observation relates to the training system within the field of Romanian research. In order to obtain good results, applicable to educational policies, solid expertise and a new academic researcher’s profile are needed, so that the balance between teaching, research and administrative tasks can be reconsidered.

5.2 At an Intervention—Organizational Level

Our research paves the way for an in-depth analysis of organizational factors likely to affect research production and transfer: engagement—interpreted as the attitude of organizations and their members towards research, the political and managerial context likely to promote and favour research transfer, and the financial context needed to foster quality results. Moreover, these institutional mechanisms may facilitate the production and transfer of research. Thus, there is a growing need for a clearer academic mission, focused on high quality research, well developed transparency and social responsibility mechanisms, as well as including the “third mission” as an academic priority. A key observation is that academic management needs to promote efficient research structures and their corresponding social transfer.

5.3 At the Macro Systemic Level of Educational Policies

The role of research is analyzed, and the focus shifts from the symbolic use of research results to a policy based on evidence. Likewise, the transparency policies promoted by Romanian higher education system are still vague and incoherent. Policy-makers are responsible for engaging as active partners in research production and use. The political implications may address the QA mechanisms likely to assess and approve research results. This should stimulate the transfer of research locally, regionally and internationally. Moreover, “mapping” mechanisms must be implemented, as well as there being fair opportunities to access research funds and infrastructures.

The links between the two contexts, at both formal and informal levels, may add value to the linkage between research production and its transfer and use. Thus, it may improve the sense of responsibility of the parties, as long as this is based on equality and mutual respect and shared responsibilities.

Notes

- 1.

According to Romanian Education Act (nr. 1/2011) the universities are divided into “advanced research and teaching” “research and teaching based universities” and “teaching based universities” (this classification was published in the HG 789/2011).

References

Bugge Bertramsen, R. (2007). National Experience Report: The Danish Case—Institutional concentration. In K. Eckhard (Ed.), Knowledge for action—Research Strategies for an Evidence-Based Education Policy. Frankfurt am Main: German Institute for International Educational Research.

Bultitude, K., Rodari, P., & Weitkamp, E. (2012). Bridging the gap between science and policy: the importance of mutual respect, trust and the role of mediators. Journal of Science Communication, 11(3), 1–4.

Cherney, A., Poveyb, J., Headb, B., Borehamb, P., & Fergusonb, M. (2012). What influences the utilisation of educational research by policy-makers and practitioners? The perspectives of academic educational researchers. International Journal of Educational Research. 56, 23–34.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (Eds.). (2005). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

European Commission (2007). Towards more knowledge-based policy and practice in education and training, SEC(2007) 1098.

European Commission (2008). Scientific evidence for policy-making. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

European Commission (2009). Consultation on the future “EU 2020” strategy. COM(2009) 647 final.

Flick, U. (2004). Introducción a la investigación cualitativa. An introduction to qualitative research. Madrid, Spain: Fundación Paideia Galiza.

Gough, D., Tripney, J., Kenny, C., & Buk-Berge, E. (2011). Evidence Informed Policy in Education in Europe: EIPEE final project report. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

Huberman, M. (1990). Linkages between researchers and practitioners: a qualitative study. American Educational Research Journal, 27(2), 363–391.

Ion, G., & Iucu, R. (2012). Impactul cercetării în ştiinţele educaţiei: perspective de studiu. Revista De Politica Ştiintei şi Scientometrie—Serie Noua, 1(2), 99–107.

Jakku-Sihvonen, R. (2007). Use of evidence: development of an evaluation culture in education. In E. Klieme (Ed.), Knowledge for action—Research strategies for an evidence-based education policy (pp. 65–98). Frankfurt am Main: German Institute for International Educational Research.

Kappel, W., & Ignat, M. (2012). Some problems of the Romanian applicative research. Revista De Politica Ştiintei şi Scientometrie—Serie Noua, 1(2), 137–141.

Lavis, J., Robertson, D., Woodside, J. M., Mcleod, C. B., & Abelson, J. (2003). How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers? Milbank Quarterly, 81(2), 221–248.

Levin, B. (2004). Making research matter more. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 12(56), 1–22.

Locke, W. (2009). Reconnecting the research—policy-practice nexus in higher education: “Evidence-Based Policy” in practice in national and international contexts. Higher Education Policy, 22, 119–140.

Lupei, V. (2012). Romanian research—where? Revista De Politica Ştiintei şi Scientometrie—Serie Noua, 1(1), 15–29.

MASIS. (2012). Monitoring Policy and Research Activities on Science in Society in Europe.

OECD (2000). Knowledge management in the learning society. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2003). New challenges for educational research. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Saunders, L. (2007). Go-betweens, gofers or mediators? Exploring the role and responsibilities of research managers in policy organisations. In L. Saunders (Ed.), Educational research and policy-making: Exploring the border country between research and policy (pp. 106–126). Oxon/New York: Routledge.

Scott, P. (2000). Higher education research in the light of a dialogue between policy-makers and practitioners. In U. Teichler & J. Sadlak (Eds.), Higher education research: its relationship to policy and practice (pp. 43–54). Oxford: Pergamon and IAU Press.

Sebba, J. (2007). Enhancing impact on policymaking through increasing user engagement in research. In L. Saunders (Ed.), Educational research and policy-making: Exploring the border country between research and policy (pp. 127–143). Oxon/New York: Routledge.

Selby-Smith, C., et al. (1992). National health labour force research program (Vols. 1–2). Melbourne: Monash University.

Simon, Z. (2012). Considerations concerning scientific education in Romania. Revista De Politica Ştiintei şi Scientometrie—Serie Noua 1(1), 69–70.

Smith, C. S. (2000). The relationships between research and decision-making in education: An empirical investigation. In: The Impact Of Educational Research Research Evaluation Programme. Commonwealth of Australia: Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs Higher Education Division.

Stegeman, H. (2007). National experience report: The Netherlands. In E. Klieme (Ed.), Knowledge for action—Research Strategies for an Evidence-Based Education Policy (pp. 65–90). Frankfurt am Main: German Institute for International Educational Research.

Teichler, U. (2000). The relationships between higher education research and higher education policy and practice: The researchers’ perspective. In U. Teichler & J. Sadlak (Eds.), Higher education research: Its relationship to policy and practice (pp. 104–135). Oxford: Pergamon/IAU Press.

Ungerleider, C. (2012). Affairs of the smart. In T. Fenwick & L. Farrell (Eds.), Knowledge mobilization and educational research (pp. 89–120). London: Routledge.

Vanderlinde, R., & Van Braaka, J. (2010). The gap between educational research and practice: views of teachers, school leaders, intermediaries and researchers. British Educational Research Journal, 36(2), 299–316.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Executive Unit for Financing Higher Education, Research, Development and Innovation (UEFISCDI) under Grant 94/2011.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License, which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Copyright information

© 2015 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ion, G., Iucu, R. (2015). Does Research Influence Educational Policy? The Perspective of Researchers and Policy-Makers in Romania. In: Curaj, A., Matei, L., Pricopie, R., Salmi, J., Scott, P. (eds) The European Higher Education Area. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0_52

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0_52

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-18767-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-20877-0

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawEducation (R0)