Abstract

Economies that thrive most on their ambitions, innovative and productive firms are due to grow and develop. Our motivation is thus to uncover who are these fast-growing firms and where they operate. These interrogations provide the foundation for an exploration into what are the different choices for policy, and an opportunity to engage afresh with why and if they ought to receive support in the first place, infusing the discussion as to when and how it could be provided and what could the intended results be. We use the dataset Quadros de Pessoal to provide a stronger twofold measurement, according to the employment and turnover growth criteria. We find among Portugal’s distinctive characteristics its high share of SMEs in the population of fast-growing firms, the narrowing down of the difference between measurements according to the employment and turnover criteria and the disproportionate amount of employment generated by the largest segment of fast-growing firms. We find that gazelles are outstanding job creators, having a disproportionately larger impact in job creation than high-growth firms. Accordingly, it is the rapid growth of a few large firms, combined with the entry of a higher number of firms of a higher average size that generates positive net job creation in Portugal. A more thorough understanding of fast-growing firms ought to lead to adjustments in government policies to heighten their exceptional contribution to economic growth. We provide a conceptual framework for tapping into how to design policies for firms which are growing at a faster pace and a roadmap for tackling some of its most controversial issues.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

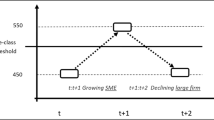

According to the European definition, (SME’s are considered firms below the 250 employees’ threshold).

- 2.

In Portugal, the estimated median duration of a newborn enterprise lies between 5 and 6 years, which is below that verified in other countries (Nunes and Sarmento 2012).

- 3.

There are, however, other theorizations. For instance, Wennekers and Thurik (1999) put forward an economic development typology based upon new enterprise formation and growth.

- 4.

A growth trigger is a “systematic change to the structure and workings of a firm which provides a critical opportunity for altering that firm’s growth trajectory” (Brown and Mawson 2013).

- 5.

In this chapter, we shall use the term “fast growing” firm to include both “high-growth” and “gazelle” enterprises.

- 6.

A minimum of 20 % growth a year for 3 consecutive years represents a minimum of 72.8 % growth over 3 years ((1.2 × 1.2 × 1.2)−1 = 0.728). According to this methodology, a firm which might have grown 72.8 % (either in turnover or in employment) within a single year with no growth in the following two does not qualify as high-growth.

- 7.

Settling the period over which growth is measured is determinant for defining what makes a high-growth firm. If the measurement period is too short (e.g., a year), firms with short-term contracts or seasonal employees might be classified as such even though their employment growth is temporary. Also, firms can live short lives and die before the start of the new measurement period, thus not being accounted for. Conversely, the period for defining high-growth firms should be long enough such that changes of a transitory nature are not erroneously accounted for as high growth. The OECD definition thus recommends a 3-year growth threshold.

- 8.

In 2007, more than 81 % of Portuguese employer enterprises had fewer than ten employees. The OECD definition thus excludes an average of approximately 175,512 firms (of a total of 215,905 firms) with fewer than ten employees from being classified as high-growth firms over the period.

- 9.

Some authors have pointed out that growth is first consummated in terms of turnover and only later on feeds into employment. From the visible fluctuations of our data, we have no account of that phenomenon, but it is an issue worth looking at in subsequent work.

- 10.

Please refer for instance to Sarmento and Nunes (2010c) for more information.

- 11.

This means that if a firm which started with the minimum required of ten employees and has to grow a minimum of 20 % during the following 3 years, it has to recruit at least two extra workers in the first year, 2.4 in the second and 2.88 in the third, ending up with a minimum required of around 17 workers at the end of the 3-year period.

- 12.

Caution must be employed when interpreting these results, as this might also be due substantially to the fact that a considerable amount of firms’ headquarters are located in the Lisbon area and that we are using enterprise and not establishment data.

- 13.

The turnover definition tends to heighten the manufacturing sector.

- 14.

During this period, high-growth firms and gazelles have been emerging considerably more in service and commerce sectors. According to the employment criteria, we observed a clear shift in the distribution of high-growth firms away from manufacturing (34 % in 1995, down to 20 % in 2007) to services and commerce (49 % in 1995 up to 56 % in 2007), as well as construction (15 % in 1995, up to 20 % in 2007). A similar pattern is observed for gazelles, although the drop in manufacturing sector is higher, it falls sharply by over a half in 13 years (42 % in 1995 to 20 % in 2007). A significant number of high-growth firms in Portugal operated in the construction sector, which was particularly hit by variations in the business cycle. This sectoral rebalancing reflects trends already perceived in the overall population of employer enterprises (Sarmento and Nunes 2010b, c).

- 15.

The challenge arises from the number of firms being a stock variable, measured at a single point in time whilst job creation, as a flow is measured between two different points in time. Consequently, this relationship also depends on the length of the measurement period.

- 16.

In the case of the present data, it refers to employees in employer enterprises in the size-class of over ten employees.

- 17.

As absolute contributions are the product of net job creation rates and the share that a category occupies in total employment.

- 18.

More static analysis account for net job creation as the difference between job gains and job losses in any given year.

- 19.

Business cycles could explain part of the dynamism of European firms (Biosca 2010).

- 20.

The pool of high-growth firms contain on average older firms than the pool of gazelles. This is also verified for Portugal using another information source applying a similar methodology (Informa D&B 2011). Stylized facts of firm dynamics also indicate that established firms, are on average, of a bigger size than new entrants.

- 21.

High-growth average firm size is larger than that of gazelles’ throughout the period.

- 22.

We cannot fully evaluate size vis-à-vis with age, as the methodology we employ restricts the analysis to firms with over ten employees. This excludes 20–30 % of Portuguese employer enterprises from the analysis.

- 23.

This can be due to data paucity, data quality constrains, and a variety of methodological issues, amongst which diversity of measurements which can disregard gross job flows in favor of a narrower emphasis on net job contribution and regression-to-the-mean effects (Haltiwanger and Krizan 1999).

- 24.

The Gazelle growth program, for instance, assists the best Danish growth companies to expand to international markets. For Finland, consider the VIGO programme Lilischkis (2013) and for Sweden Bornefalk and Du Rietz (2009). For France, see Betbèze and Saint-Étienne (2006), for Germany consider the IMProve project, for instance. For Scotland consider Brown and Mawson (2013) and for Canada, Herman and Williams (2013). For the United States, consider the initiative Start-up America and for New Zealand see Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2013) and New Zealand Government (2013).

- 25.

From the 87 % of Portuguese micro-firms existing between 1991 and 2009 in the Bank of Portugal’s Central de Balanços database, only ten grew into large firms (Banco de Portugal 2010).

- 26.

Stam et al. (2012) labels an “ambitious entrepreneur” as someone who engages in the entrepreneurial process with the aspiration to create as much value as possible. Schoar (2010) contends that only a small percentage of entrepreneurs are likely to succeed in scaling-up their businesses towards increasing profits and creating jobs, putting forward a distinction between “subsistence” and “transformational” entrepreneurs.

- 27.

- 28.

Since 2011, it has been replaced by the Conselho Estratégico de Internacionalização da Economia or CEIE.

- 29.

This is particularly important for gazelles, as its growth tends to be highly concentrated over a short period of time.

- 30.

The aim and focus of the intervention also influences the choices of targets made later on, and the former also influences subsequently the type of resource allocation. Traditional SME focused policies are mostly supported by public funds, with a little support going to many agents, thus privileging quantity instead of quality. Focusing on fast-growing firms entails a somehow different focus, on quality and on the allocation of relatively more funds to a fewer number of firms, possibly through a mix of public and private funding.

- 31.

This has also been the principle applied by the European Union, where policies designed at the supranational level can be left to be adapted regionally, making use of the principle of subsidiarity.

- 32.

- 33.

An analysis of Swedish firms suggests that the strict application of the Eurostat/OECD definition excluded about 95 % of all surviving firms, creating 39 % of all new jobs during the period (Daunfeldt et al. 2012).

- 34.

- 35.

References

Acevedo GL, Tan HW (eds) (2011) Impact evaluation of small and medium enterprise programs in Latin America and the Caribbean. World Bank, Washington, DC

Acs ZJ, Mueller P (2008) Employment effects of business dynamics: mice, gazelles and elephants. Small Bus Eco 30(1):85–100

Acs ZJ, Parsons W, Tracy S (2008) High impact firms: gazelles revisited. Research summary 328. Office of Advocacy, U.S. Small Business Administration, Washington, DC

Ahmad N (2008) A proposed framework for business demography statistics. In: Congregado E (ed) Measuring entrepreneurship: building a statistical system, vol 16. Springer, New York, pp 113–174. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-72288-7_7

Anyadike-Danes M, Bonner K, Hart M, Mason C (2009) Measuring business growth: high-growth firms and their contribution to employment in the UK. NESTA research report, Oct 2009. NESTA, London

Anyadike-Danes M, Hart M, Du M (2013) Firm dynamics and job creation in the UK—taking stock and developing new perspectives White Paper 6. Enterprise Research Centre, Warwick Business School, Coventry

Audretsch DB, Feldman MP (1996) R&D spillovers and the geography of innovation and production. Am Econ Rev 86(4):253–273

Autio E, Kronlund M, Kovalainen A (2007) High-growth SME support initiatives in nine countries: analysis, categorization and recommendations. Edita, Finland

Baldwin JR, Dupuy R, Picot G (1996) Have small firms created a disproportionate share of new jobs in Canada? A reassessment of the facts, vol 71, Analytical studies branch. Statistics Canada, Ottawa

Banco de Portugal (2010) Estrutura e dinâmica das Sociedades não financeiras em Portugal. Estudos da Central de Balanços. Banco de Portugal, Lisboa

Barbosa N, Eiriz V (2011) Regional variation of firm size and growth: the Portuguese case. Growth and Change 42(2):125–158

Bartelsman E, Scarpetta S, Schivardi F (2005) Comparative analysis of firm demographics and survival: evidence from micro-level sources in OECD countries. Ind Corp Change 14(3):365–391

Basu K (2013) The method of randomization, economic policy, and reasoned intuition. Policy research working paper 6722. World Bank, Washington, DC

Betbèze JP, Saint-Étienne C (2006) Une stratégie PME pour la France. Conseil d’Analyse Economique, La Documentation française

Biosca AB (2010) Growth dynamics, exploring business growth and contraction in Europe and the US. NESTA and FORA Research Report. NESTA, London

Birch DL (1979) The job generation process. MIT program on neighborhood and regional change, 302. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge

Birch DL (1981) Who creates jobs? Public Interest 65:3–14

Birch DL (1987) Job creation in America: how our smallest companies put the most people to work. Free Press, New York

Birch DL, Haggerty A, Parsons W (1995) Who is creating jobs? Cognetics, Boston

Birch DL, Haggetty A, Parsons W (1997) Corporate almanac. Cognetic, Cambridge

BIS (2011). The plan for growth. Department of Business, Innovation and Skills. BIS—Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, HM Treasury, England

Bornefalk A, Du Rietz A (2009) Entrepreneurship policies in Denmark and Sweden—targets and indicators. Swedish Network for European Studies in Economics and Business, Stockholm, http://www.snee.org/publikationer_search_eng.asp

Bornhäll A, Daunfeldt S, Rudholm N (2013) Sleeping gazelles: high profits but no growth. HUI Working Papers 91. HUI Research, Stockholm

Bos J, Stam E (2011) Gazelles, industry growth and structural change. Research Memoranda 18. Maastricht Research School of Economics of Technology and Organization (METEOR), Maastricht

Bosma N, Schutjens V (2007) Patterns of promising entrepreneurial activity in European regions. Tijdschrift voor ecconomische en sociale Geografie 98(5):675–686

Bosma N, Schutjens V (2011) Understanding regional variation in entrepreneurial activity and entrepreneurial attitude in Europe. Ann Reg Sci 47(3):711–742

Bosma N, Stam E (2012) Local policies for high-employment growth enterprises. In: Report prepared for the OECD/DBA international workshop on high-growth firms: local policies and local determinants, Copenhagen

Brown R, Mawson S (2013) Trigger points and high-growth firms: a conceptualisation and review of public policy implications. J Small Bus Enterprise Dev 20(2):279–295

Brüderl J, Preisendörfer P (2000) Fast-growing businesses: empirical evidence from a German study. Int J Sociol 30(3):45–70

CPA Australia/CGA-Canada (2010). Report of the forum on SME issues: unlocking the potential of the SME sector. CPA Australia/CGA-Canada

Câmara de Comércio Americana em Portugal (2012) Intrapreneurship Portugal. CCAP, Lisboa

Capital GE (2013) PME-ETI: sommet pour la croissance, les secrets de ces entreprises de taille moyenne qui font la France. EPCE, França

Caves RE (1998) Industrial organization and new findings on the turnover and mobility of firms. J Econ Lit 36(4):1947–1982

Chandler GN, Lyon DW (2001) Issues of research design and construct measurement in entrepreneurship research: the past decade. Entrepren Theory Pract 25(4):101–113

Churchill NC, Lewis VL (1983) The five stages of small business growth. Harv Bus Rev 61(3):30–50

Commission E (2010) Europe 2020: a strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth: communication from the Commission. Research report. European Commission, Brussels

Dalton S, Friesenhahn E, Spletzer J, Talan D (2011) Employment growth by size-class: comparing firm and establishment data. Monthly Labor Review 1–12 Dec

Daunfeldt S, Halvarsson D, Johansson D (2012) A cautionary note on using the Eurostat-OECD definition of high-growth firms HUI Working Papers 65. HUI Research, Stockholm

Davidsson P, Delmar F (2006) High-growth firms and their contribution to employment: the case of Sweden 1987-96. In: Davidsson P, Delmar F, Wiklund J (eds) Entrepreneurship and growth of the firm. Edward Elgar, Chelten, pp 7–20

Davidsson P, Wiklund J (2000) Conceptual and empirical challenges in the study of firm growth. In: Sexton D, Landström H (eds) The Blackwell handbook of entrepreneurship. Blackwell Business, Oxford, pp 26–44

Davidsson P, Achtenhagen L, Naldi L (2005) Research on small firm growth: a review. In: European Institute of Small Business

Davidsson P, Achtenhagen L, Naldi L (2010) Small firm growth. Found Trends Entrepren 6(2):69–166

Davis SJ, John CH, Scott S (1996) Job Creation and Destruction. The MIT Press, Cambridge. MA

Delmar F, Davidsson P, Gartner W (2003) Arriving at the high-growth firm. J Bus Ventur 18:189–216

ECB (2012) Euro area labour markets and the crisis, vol 138, Occasional paper series. European Central Bank, Frankfurt

Ernst & Young (2013) L’efficacité des aides publiques aux entreprises, Quelles priorités pour la compétitivité française? Ernst & Young, France

Europe INNOVA (2011) Gazelles, high-growth companies. Final Report, Consortium Europe INNOVA Sectoral Innovation Watch: European Commission

European Cluster Observatory (2009). Priority sector report: knowledge intensive business services. Center for Strategy and Competitiveness, Stockholm School of Economics, Europe INNOVA Initiative.

European Investment Bank (2005) Evaluation of SME global loans in the enlarged Union. Evaluation report, operations evaluation. EIB, Luxemburg

European Parliament (2011) Glasgow: Directorate General for Internal Policies. Directorate General for Internal Policies, Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies, EPRC, Glasgow

Eurostat/OECD (2007) Eurostat-OECD manual on business demography statistics. OECD, Paris

Entrepreneurship indicators: Employer business demography and high-growth enterprises in Europe, 21st Meeting of the Wiesbaden Group on Business Registers — International Round Table on Business Survey Frames, Session 6A: Entrepreneurship indicators, Business Demography and SMEs (Nov 2008), Paris

Felício JA, Rodrigues R, Caldeirinha VR (2012) The effect of intrapreneurship on corporate performance. Manage Decis 50(10):1717–1738

Financial Times (2014) British business bank to target SMEs with potential. Accessed Jan 5, 2014. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/8fe98c74-6969-11e3-89ce-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2pueHPul2

Fritsch M (2011) The effect of new business formation on regional development: empirical evidence, interpretation, and avenues for further research. In: Fritsch M (ed) Handbook of research on entrepreneurship and regional development (Chapter 4). Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 58–106

Fritsch M, Mueller P (2006) The evolution of regional entrepreneurship and growth regimes. In: Fritsch M, Schmude J (eds) Entrepreneurship in the region (Chapter 11). Springer Science, New York, pp 225–244. doi:10.1007/0-387-28376-5_11

Garnsey E, Stam E, Heffernan P (2006) New firm growth: exploring processes and paths. Ind Innov 13(1):1–20

GEM (2012) GEM Portugal 2012: estudo sobre o empreendedorismo. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Portugal

Gibrat R (1931) Les inegalités économiques. Recueil Sirey, Paris

Gilbert B, McDougall P, Audretsch D (2006) New venture growth: a review and extension. J Manag 32:926–950

Gilbert BA, McDougall P, Audretsch DB (2008) Clusters, knowledge spillovers and new venture performance: an empirical examination. J Bus Ventur 23(4):405–422

Goldman Sachs (2013) Stimulating small business growth, Progress Report on the Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses UK Programme. Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses in a joint collaboration with the University of Oxford, Aston Business School, University of Leeds, Manchester Metropolitan University and UCL

Greiner LE (1972) Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. Harv Bus Rev 76(3):37–46

Haltiwanger J, Krizan CJ (1999) Small business and job creation in the United States: the role of new and young businesses. In: Acs ZJ (ed) Are small firms important? Their role and impact (Chapter 5). Kluwer Academic, Boston, pp 79–97

Haltiwanger JC, Jarmin RS, Miranda J (2013) Who creates jobs? Small vs. large vs. young. Rev Econ Stat 95(2):347–361. doi:10.1162/REST_a_00288

Henrekson M, Johansson D (2009) Competencies and institutions fostering high-growth firms. Found Trend Entrepren 5(1):1–80

Henrekson M, Johansson D (2010) Gazelles as job creators—a survey and interpretation of the evidence. Small Bus Econ 35(2):227–244

Herman D, Williams AD (2013) Driving Canadian growth and innovation: five challenges holding back small and medium-sized enterprises in Canada. Centre for Digital Entrepreneurship and Economic Performance, Canada

Hölzl W (2009) Is the R&D behaviour of fast-growing SMEs different? Evidence from CIS III data for 16 countries. Small Bus Econ 33(1):59–75

Informa D&B (2011) Crescimento do tecido empresarial 2006–2009. 1º Conferência sobre crescimento empresarial e empresas de elevado crescimento em Portugal, Lisboa

Jaffe AB, Trajtenberg M, Henderson R (1993) Geographic localization of knowledge spillovers as evidenced by patent citations. Q J Econ 108(3):577–598

KPMG (2012) Voyage au cœur des entreprises de taille intermédiaire (ETI): une stratégie de conquêtes. KPMG, France

KPMG & CGPME (2012). Panorama de l’évolution des PME depuis 10 ans. Cahier Préparatoire. KPMG, France

KPMG (2013) Les ETI, leviers de la croissance en France, cinq ans après leur création, quel bilan et quelles perspectives? KPMG, France

Lawless M (2013) Age or size? Determinants of job creation. Research Technical Paper 2/RT/13. Central Bank and Financial Services Authority of Ireland, Dublin

Lechner C, Dowling M (2003) Firm networks: external relationships as sources for the growth and competitiveness of entrepreneurial firms. Entrepren Reg Dev 15(1):1–16

Lerner J (1999) The government as a venture capitalist: the long-run effects of the SBIR program. J Bus 72(3):285–297

Levie J, Lichtenstein BB (2010) A terminal assessment of stages theory: introducing a dynamic states approach to entrepreneurship. Entrepren Theory Pract 34:317–350

Lilischkis S (2013) Policies in support of high-growth innovative SMEs. Discussion paper for the 2013 ERAC mutual learning seminar on research and innovation policies, Brussels

McKinsey Global Institute (2010) Beyond austerity: a path to economic growth and renewal in Europe. McKinsey, Chicago

Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (2013) High-growth business in New Zealand. Research evaluation and analysis branch. Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, Wellington

Mitusch K, Schimke A (2011) Gazelles—high-growth companies. Task 4 Horizontal Report 5 (Final Report). Europe INNOVA Sectoral Innovation Watch for DG Enterprise and Industry, European Commission

Morris M, Stevens P (2009) Evaluation of the growth services range: statistical analysis using firm-based performance data. Ministry of Economic Development, Government of New Zealand, New Zealand

NESTA (2009) The vital 6 per cent: how high-growth innovative businesses generate prosperity and jobs. NESTA Research Summary (Oct 2009). NESTA, London

NESTA (2011) Vital growth: the importance of high-growth business to the recovery. NESTA Research Summary (March 2011). NESTA, London

New Zealand Government (2013) Information and communications technology. The New Zealand Sectors Report 2013. Ministry of Business, Innovation, and Employment, Wellington

Nordic Council of Ministers (2010) Nordic entrepreneurship monitor 2010. NCM, Copenhagen

Nunes A, Sarmento EM (2012) Business demography dynamics in Portugal: a non-parametric survival analysis. In: Bonnet J, Dejardin M, Madrid-Guijarro A (eds) The shift to the entrepreneurial society: a built economy in education, sustainability and regulation (Chapter 18). Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 260–272. doi:10.4337/9780857938947.00027

OECD (1997) Small business, job creation and growth: facts, obstacles and best practices. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris

OECD (2002) High-growth SMEs and employment. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris

OECD (2007) OECD framework for the evaluation of SME and entrepreneurship policies and programmes. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris. doi:10.1787/9789264040090-en

OECD (2008) Measuring entrepreneurship: a digest of indicators. OECD-Eurostat Entrepreneurship Indicators Programme. OECD Statistics Directorate, Paris

OECD (2009) Measuring entrepreneurship: a collection of indicators (2009 edn) OECD-Eurostat Entrepreneurship Indicators Programme. OECD Statistics Directorate, Paris

OECD (2010) High-growth enterprises: what Governments can do to make a difference. OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris. doi:10.1787/9789264048782-en

OECD (2011) Entrepreneurship at a Glance 2010, Paris

OECD (2012) OECD economic surveys: Portugal 2012. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris. doi:10.1787/eco_surveys-prt-2012-en

OECD (2013a) Key findings of the work of the OECD LEED programme on high-growth firms—interim report. Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs and Local Development, CFE/LEED, Paris

OECD (2013b) Entrepreneurship at a glance 2013. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris. doi:10.1787/entrepreneur_aag-2013-en

Parker SC, Storey DJ, Van Witteloostuijn A (2010) What happens to gazelles? The importance of dynamic management strategy. Small Bus Econ 35(2):203–226

Picot G, Dupuy R (1998) Job creation by company size class: the magnitude, concentration and persistence of job gains and losses in Canada. Small Bus Econ 10(2):117–139

Porter ME (1998) Clusters and competition: new agendas for companies, governments, and institutions. In: Porter ME (ed) On competition. Harvard Business School Press, Boston, pp 197–299

Santander (2013) Growth Britain: unlocking the potential of our SMEs. Santander report 2013

Salas OA, Francolí, Gascón JFJM, Stoyanova A (2010) High-growth firmsand gazelles in Catalonia, Generalitat di Catalunya

Sarmento EM, Nunes A (2010a) Getting smaller: size dynamics of employer enterprises in Portugal. In: Lechman E (ed) Enterprise in modern economy—SMEs and entrepreneurship, vol 2. Gdańsk University of Technology Publishing House, Poland, pp 118–138

Sarmento EM, Nunes A (2010b) Entrepreneurship performance indicators for active employer enterprises in Portugal. Temas Económicos 9/2010. Gabinete de Estratégia e Estudos, Ministério da Economia, da Inovação e do Desenvolvimento, Portugal

Sarmento EM, Nunes A (2010c) Business demography in Portugal. Statistical publications. Gabinete de Estratégia e Estudos, Ministério da Economia, da Inovação e do Desenvolvimento, Lisboa

Sarmento EM, Nunes A (2012) The dynamics of employer enterprise creation in Portugal over the last two decades: a size, regional and sectoral perspective. Notas Económicas 36:6–22

Schoar A (2010) The divide between subsistence and transformational entrepreneurship. Innov Pol Econ 10:57–81

Schreyer P (1996) SMEs and employment creation: overview of selected quantitative studies in OECD Member Countries. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, 1996/04. OECD, Paris. doi:10.1787/374052760815

Schreyer P (2000) High-growth firms and employment. OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, 2000/3. OECD, Paris. doi:10.1787/861275538813

Siegel D, Westhead P, Wright M (2003) Science parks and the performance of new technology-based firms: a review of recent UK evidence and an agenda for future research. Small Bus Econ 20(2):177–184

Stam E (2005) The geography of gazelles in the Netherlands. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Social Geografie 96(1):121–127

Stam E, Stel A (2011) Types of entrepreneurship and economic growth. In: Szirmai A, Naudé W, Goedhusys M (eds) Innovation, entrepreneurship and economic development (Chapter 4). Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 78–95

Stam E, Hartog C, Van Stel A, Thurik R (2011) Ambitious entrepreneurship and macro-economic growth. In: Minniti M (ed) The dynamics of entrepreneurship. Evidence from the global entrepreneurship monitor data (Chapter 10). Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 231–250

Stam E, van Bosma N, Witteloostuijn A, de Jong J, Bogaert S, Edwards N, Jaspers F (2012) Ambitious entrepreneurship: a review of the state of the art. Studie Reeks 23. Vlaamse Raad voor Wetenschap en Innovatie, Flemish Council for Science and Innovation, Brussels

Stangler D (2010) High-growth firms and the future of the American economy, vol 2, Kauffman Foundation research series: firm formation and economic growth. Kauffman Foundation, Kansas City

Steffens P, Davidsson P, Fitzsimmons J (2009) Performance configurations over time: implications for growth- and profit-oriented strategies. Entrepren TheoryPract 33(1):125–148

Storey D (1994) Understanding the small business sector. Routledge, London

Sutton J (1997) Gibrat’s legacy. J Econ Lit 35:40–59

Swedish Agency for Growth Policy Analysis (2011) Entrepreneurship and SME-policies across Europe—the cases of Sweden, Flanders, Austria and Poland. Report 2010/31, Swedish Agency for Growth Policy Analysis

Tamásy C (2006) Determinants of regional entrepreneurship dynamics in contemporary Germany: a conceptual and empirical analysis. Reg Stud 40(4):364–384

Tilford S, Whyte P (eds) (2011) Innovation, how Europe can take off. Centre for European Reform, London

Van Praag MC, Versloot PH (2008) The economic benefits and costs of entrepreneurship: a review of the research. Found Trends Entrepren Res 42(2):65–154

Wennekers S, Thurik R (1999) Linking entrepreneurship and economic growth. Small Bus Econ 13(1):27–55

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento of the Portuguese Ministry of Labor and Social Security for the provision of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

de Morais Sarmento, E., Nunes, A. (2015). Entrepreneurship, Job Creation, and Growth in Fast-Growing Firms in Portugal: Is There a Role for Policy?. In: Baptista, R., Leitão, J. (eds) Entrepreneurship, Human Capital, and Regional Development. International Studies in Entrepreneurship, vol 31. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12871-9_17

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12871-9_17

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-12870-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-12871-9

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsBusiness and Management (R0)