Abstract

Lowland and montane forests can be distinguished as being distinct floristically and by their structural characters. Soil and climatic factors are primary determinants of changes in community structure and species composition. Field surveys were undertaken in the pristine forests of Imbak Canyon, Sabah and Mount Ledang, Johor, Malaysia. While these areas provide long-term maintenance and fully protected habitats of biological diversity, the floristic composition still remains rather insufficiently known. Therefore, this study has three objectives: (1) to identify the major forest types and tree communities, (2) to study changes in species composition along altitudinal gradients, and (3) to document the list of tree species collected in the study areas. The survey in Imbak Canyon resulted in the documentation of 40 families of the Angiosperms and Gymnosperms comprising 85 genera and 149 taxa. The areas are rich with tree species from the families of Dipterocarpaceae, Guttiferae, Lauraceae, Leguminosae, and Myristicaceae. Trees from Podocarpaceae family are common montane taxa occurred in highest peak of ridge trail such as Podocarpus neriifolius, Dacrydium elatum, Phyllocladus sp., and Falcatifolium falciforme. An interesting finding was the occurrence of Shorea monticola (Dipterocarpaceae) in the summit zone of montane heath forest, whereas in Mount Ledang, a total of 62 tree families were encountered which consist of 62 families, 143 genera, and 222 taxa. Overall, Mount Ledang is rich with the tree species from the families of Myrtaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Moraceae, Dipterocarpaceae, and Rubiaceae. Common montane taxa encountered include trees from Podocarpaceae family (i.e., Podocarpus neriifolius, Dacrydium elatum, and Dacrydium beccarii). An interesting finding was the discovery of Maesa fraseriana (Maesaceae) in the upper montane forest of Mount Ledang which can potentially be a new record for the area. Information from this survey may provide a valuable reference for forest assessments, and improving our knowledge in identification of ecologically useful species as well as species of special concern, thus identify conservation efforts for sustainability of forest biodiversity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

19.1 Introduction

Due to the variation in biogeography, habitat, and disturbance, tree species in tropical forest varies greatly from place to place in terms of composition and diversity (Whitmore 1998). Altitudinally, the changes in community structure and species composition are influenced by the variation of soil and climatic factors. In addition, other factors such as historical processes, biotic interaction, competition, natural disturbance, and microclimatic are being recognized to play important roles.

In Malaysia, five forest zones are developed from climatic climax formations, i.e., lowland Dipterocarp forest (0–300 m above sea level, (a.s.l.)), hill Dipterocarp forest (300–800 m a.s.l.), upper hill Dipterocarp forest (800–1100 m a.s.l.), oak laurel forest (1100–1600 m a.s.l.) and montane ericaceous forest (above 1600 m a.s.l.), and (Symington 2004). These forests are characterized by species composition. The first three forest types are mostly dominated by trees from the Dipterocarpaceae family, hence they are termed as dipterocarp forests. Montane ericaceous and oak-laurel are characterized by an abundance of trees from Fagaceae–Lauraceae and Ericaceae families, respectively. They can be distinguished by a number of structural characters which include the size of canopy height, canopy layer, leaves, and the presence of vascular and nonvascular epiphytes and climbers (Table 19.1). The montane forest also differs from lowland in having fewer and smaller emergent trees, flattish canopy surfaces, gnarled limbs, and denser sub-crowns (Whitmore 1984). The montane ericaceous and oak-laurel forests are moist and are characterized by a thick layer of moss and bryophytes.

In Peninsular Malaysia, montane rainforest communities are scattered and few. With the exception of Cameron Highlands and Fraser’s Hill, they are mainly minimally disturbed, undisturbed, or totally protected such as Gunung Benom in Krau Wildlife Reserve (Latiff and Mohd Shaffea 2011) and Gunung Tahan in Taman Negara Pahang. While both montane ericaceous and oak-laurel forests occupy a relatively small land area in the country, according to Soepadmo (1987), about 25 % of flora in Peninsular Malaysia is confined to these forests. This suggests that floristic composition of montane can be considered as rich in species which is partly due to endemism.

Despite being recognized as among the oldest pristine tropical rain forests in Malaysia, the uniqueness and endemic variety of flora of Imbak Canyon and Mount Ledang have not been fully explored and is scientifically documented. In recognizing the need of providing an inventory of tree species occurring in this area, this chapter aims at identifying the major forest types and tree communities in these areas, studying changes in tree species along altitudinal gradients and presenting the list of tree species collected in the these two areas ranging from lowland forest extending to hill, upper hill, montane, and oak-laurel forest trails. Such basic information is of importance to the understanding of the species distribution, conservation requirements, and economic potential of tree resources which may contribute towards developing and managing the available resources on a sustainable basis.

19.2 Material and Methods

19.2.1 Study Areas

19.2.1.1 Imbak Canyon, Sabah

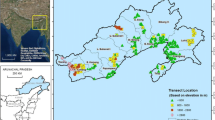

Imbak Canyon is located on the south of Telupid (5°6ʹ34.49″°N, 117°0ʹ9.01″ E) within the Sabah Foundation Conservation Area in the state of Sabah, Malaysia (Fig. 19.1). Landscape of Imbak Canyon is varied from nearly flat, low undulating with river valleys to the hill and montane forest habitats (Fig. 19.2). The orientation and shape of the canyon follow the main river system of Imbak River. The floor of the 25-km canyon lies about 150 m a.s.l., whereas the rim of Canyon rises to more than 1500 m a.s.l. Imbak Canyon is part of Borneo, the third largest island in the world and has been acknowledged as one of the most well-known centers of plant diversity in the world (Soepadmo and Wong 1995). In certain localities in Sabah, where extensive botanical exploration has been conducted, much has been written that the species diversity is extremely high. For example, according to Beaman and Beaman (1990), the Mount Kinabalu Park contains not less than 4000 species of vascular plants in 180 families and 980 genera.

19.2.1.2 Mount Ledang National Park, Johor

Mount Ledang, also known as Mount Ophir, is a mountain situated at Gunung Ledang National Park (2°22′27″ N, 102°36′28″ E) in the state of Johor, Malaysia (Fig. 19.1). The mountain is standing at an altitude of 1276 m a.s.l. in the area of 8675.2 ha, and is located between the states of Johor and Malacca. Mount Ledang was gazzetted as a National Park in 2003. The park holds four distinct vegetation types which include lowland dipterocarp forest, hill dipterocarp forest, lower montane, and montane ericaceous.

19.2.1.3 Specimen Collection

Specimen collections in Imbak Canyon were conducted in three localities, viz: (1) the vicinity of the principal base camp of Mount Kuli Research Station, (2) along the riparian forests from the base camp to waterfall (referred to as Riverine trail), and (3) along the forest trail from base camp to the highest point of heath montane forest (known as Ridge trail) (Fig. 19.1). In Mount Ledang, botanical specimens were collected at two trails. These were (1) the forest trail from dam base camp to the upper montane forest at the plateau base camp and continued to the highest point where the telecommunication tower was erected (Fig. 19.3), and (2) along the riparian forest from the park rangers’ office.

During the surveys in both locations, attempts were made to make a collection of fresh leaves along with flowers or fruits with the assistance from tree climbers. As collecting complete specimens from canopy tree is often difficult, fallen leaves, fruits, and flowers were collected from the ground. Specimens collected, where possible, were identified during the collection. A GPS receiver was used to determine the topographic elevation of the specific points in the trails. Trail elevation profiles for Imbak Canyon and Mount Ledang were then produced to study the altitudinal changes in tree species distribution along the gradients.

All botanical specimens collected were deposited in the herbarium laboratory of the Centre of Biodiversity and Sustainable Development, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Puncak Alam, Malaysia. Whenever possible, the conservation status of the species was cross-checked with the information from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red Listdatabase (IUCN 2013). The IUCN red list provides taxonomic, conservation status, and distribution information on taxa that are facing a risk of extinction.

19.3 Results and Discussion

All tree species collected from Imbak Canyon and Mount Ledang were identified and are alphabetically listed in Appendix 1. For Imbak Canyon, the Sabah’s vernacular names in the list were referred from the Preferred Check-List of Sabah Trees (Sabah Forestry Department 2005). Whenever possible, the conservation status for the species listed were included based on the information from the IUCN Red List (IUCN 2011).

19.3.1 Tree Communities of Imbak Canyon

From the analysis, it was observed the pristine Imbak Canyon forest holds a high diversity of trees. In all study sites combined, the total number of tree families enumerated along the study trails amounted to 40. Figure 19.4 shows the distribution of tree families found in the study areas in relation to the number of taxa they belong to. Detailed analysis on individual specimens revealed that the families consist of a total of 85 genera and 149 taxa. In terms of tree family, the areas surveyed are rich with the species from the family of Dipterocarpaceae. Specifically, a total of 38 taxa from Dipterocarpaceae family were encountered in the study trails. The second common family is Guttiferae with 13 taxa, followed by Lauraceae (9 taxa), and Leguminosae and Myristicaceae, both account for 8 taxa from the total taxa encountered during the survey periods. Other important families that occur in the study trails include Burseraceae, Euphorbiaceae, Myrtaceae, Rubiaceae, Sterculiaceae, and Podocarpaceae.

19.3.1.1 Riverside Forest and Stream Vegetation

Within and outside the principal base camp in Imbak Canyon are riparian forests that harbor some interesting plant life. Elevation profile of riverine trial associated with the common tree species encountered in the expedition trails is shown in Fig. 19.5. Smaller trees and treelets that are especially common in the riparian forests include Psychotria sp., Rennellia speciosa (Rubiaceae), Calophyllum obliquinervium (Guttiferae), Canarium denticulatum (Burseraceae), and Dillenia excelsa (Dilleniaceae). Tree species from Dipterocarpaceae (i.e., Dipterocarpus kunstleri, Shorea macrophylla, Shorea parvifolia, and Parashorea tomentella) are common big trees encountered on both flat ground and farther away from the stream. Besides these, Hopea nervosa was frequent and easy to identify by its stilt roots. Below canopy level, the medium-sized to smaller tree species found include Casearia clarkei (Flacourtiaceae) and Neesia sp. (Bombacaceae). Joining the medium-sized trees are a number of canopy-height trees including Octomeles sumatrana (Datiscaceae), Lithocarpus curtisii (Fagaceae), and Duabanga moluccana (Sonneratiaceae), the latter is characterized by its monopodial branching. A common emergent non-dipterocarp tree species along the riverside is Koompassia excelsa (Leguminosae). In openings or gaps of the stream banks, it is not usual to find pioneer species of Artocarpus anisophyllus (Moraceae), Macaranga triloba, Macaranga hypoleuca, and Macaranga gigantea (Euphorbiaceae). Along some open banks and forest edges, the small tree Vitex pinnata (Verbanaceae) and Leea indica (Leeaceae) are occasionally found.

19.3.1.2 Lowland, Hill, and Upper Dipterocarp Forests

Figure 19.6 shows an elevation profile of the ridge trail that shows altitudinal changes of tree species. Lowland dipterocarp forests in the expedition areas of Imbak occur from 270 m a.s.l. As the name implies, an interesting character of the lowland dipterocarp forest is the occurrence of dipterocarps within six out of nine genera. These include Shorea johorensis, Dipterocarpus caudiferus, Parashorea tomentella, Hopea nervosa, Vatica maingayi, and Dryobalanops lanceolata.

Many other groups of plants contribute to the complexity of the forest in Imbak Canyon. A variety of palms (tall palms, understorey palms, and rattans) are especially common, while lianas and epiphytes are frequently encountered in the lowland forests. Small trees that are common in this area include Glochidion borneensis (Euphorbiaceae), Magnolia sp. (Magnoliaceae), Actinodaphne pruinosa (Lauraceae), and Fordia curtisii (Leguminosae), whereas the common medium-sized trees include Knema stenophylla subsp. longipedicellate, Horsfieldia polyspherula (Myristicaeae), Heritiera javanica (Sterculiaceae), Mezzettia leptopoda (Anonaceae), and Garcinia sp. (Guttiferae). Horsfieldia and Knema can be identified by their red sap from the inner bark. Along the trail, different tree communities were observed towards higher elevation to ridge trail. Here, Tristaniopsis whiteana (Myrtaceae) is common, distinctive by its peeling barks with mixed reddish brown to gray-white hues. Diospyros wallichii (Ebenaceae) grows occasionally and is conspicuous in this forest by its black bark. Other tree includes Gluta aptera (Anacardiaceae), which can be identified among other trees by its black sap from the inner bark.

Within the hill dipterocarp forests, tree species from the genus of Shorea (Dipterocarpaceae) are common big trees encountered along the trails. These include Shorea obscura, Shorea laevis, Shorea maxwelliana, and Shorea guiso. They are much encountered on the upper hill dipterocarp forests. Together with these emergent dipterocarps are a number of big non-dipterocarp trees such as Lithocarpus ewyckii (Fagaceae), Parinari oblongifolia (Chrysobalanaceae), Campnosperma squamatum (Anacardiaceae), and Sindora echinocalyx (Leguminosae). Smaller trees occasionally encountered along the upper hill forests include Lasianthus sp. (Rubiaceae), Dysoxylon sp. (Meliaceae), Payena maingayi (Sapotaceae), and Polyalthia cauliflora (Anonaceae). At the time of the study, Polyalthia cauliflora was among a few flowering trees with the inflorences borne on the main trunk.

19.3.1.3 Lower Montane Forest

Lower montane forest was observed before the peak of ridge trails with the presence of lower montane vegetation at 895 m a.s.l. At this elevation, dipterocarps and other common lowland families such as Leguminosae, Euphorbiaceae, and Myristiceae begin to diminish and replace by a diversity of species from tree families such as Myrtaceae, Fagaceae, and Lauraceae. At this elevation, Syzygium sp. (Myrtaceae), and Calophyllum nodusum, Calophyllum depresinervosum (Guttiferae), and Schefflera sp. (Araliaceae) form the main tree association. At 950 m altitude, the forest is mossy and is characterized with low-statured vegetation and devoid of emergent trees.

19.3.1.4 Summit Zone of Ridge Trail

The summit zone occurs on the ridge trail (1080 m a.s.l), among highest peaks in Imbak Canyon. The forest type in summit zone is montane heath forest. Heath forest, also known as kerangas forest occurs on acidic sandy soils that are result of the area’s siliceous parent rocks. Within the summit zone, trees from the family of Podocarpaceae are very common montane taxa such as Podocarpus neriifolius, Dacrydium elatum, Falcatifolium falciforme, and Phyllocladus sp. The first two species are much encountered before the summit, whereas Falcatifolium falciforme and Phyllocladus sp. are distinctly common around the summit zone. This elevation zone also supports a large variety of pitcher plants. Other montane taxa such as Acronychia sp. (Rutaceae) as well as Lindera montanoides (Lauraceae) also occur. An interesting finding of the montane health forest of Imbak Canyon is the occurrence of the only dipterocarp Shorea monticola in the summit zone despite its absence in the lower elevation (Fig. 19.5).

19.3.2 Tree Species of Special Interest in Imbak Canyon

Imbak Canyon is an interesting conservation area in terms of landscape variation and conservation potential. It shelters species that are endemic to the area although they may be found in other parts of Borneo. Of all trees documented, four taxa are reported to be endemic to Borneo. These include Knema stenophylla subsp. longipedicellate, Dryobalanops lanceolata, Actinodaphne montana, and Shorea monticola (Appendix 1). Knema stenophylla subsp. longipedicellate normally occurs in lowland dipterocarp forest to lower montane forests (de Wilde 2000). In this survey, the species was found at the ridge trail of about 795 m a.s.l. Ashton (2004) reported that Dryobalanops lanceolata is common and widespread in Sabah, Sarawak, and Brunei. In this study, this taxon was observed to form abundant saplings under the closed canopy mostly on the lowland areas and lower slopes up to 700 m altitude.

Shorea monticola is another endemic species of Borneo commonly found in the upper limits of upper dipterocarp forests at 600–1500 m altitude. In Imbak Canyon area, this species is found at the peak of ridge trail of 1080 m altitude. Ashton (2004) reported that this taxon also commonly occurs in Kinabalu National Park and Mulu National Park in Sarawak.

The IUCN Red List data were used to provide the information on the conservation status of some of listed tree species collected from this survey. Based on the list, five species from the family of Dipterocarpaceae, viz, Parashorea malaanonan, Vatica maingayi, Dipterocarpus grandiflorus, Dipterocarpus kunstleri, and Shorea johorensis, are reported to be critically endangered (Appendix 1) which may require a combination of sound research and some conservation attention.

19.3.3 Forest Communities and Tree Flora of Mount Ledang

19.3.3.1 Family of Trees

Mount Ledang equally holds a high diversity of trees with a total number tree families enumerated from all study areas amounting to 62. Figure 19.7 shows the distribution of tree families that occur in the study area in relation to the number of taxa. Observations of specimens indicated that the tree families consist of 143 genera and 222 taxa. Generally, the areas surveyed are rich with the species from the family of Myrtaceae. Overall, a total of 24 taxa which belong to Myrtaceae family were encountered in the study trails. The second was the family of Euphorbiaceae with 21 taxa, followed by Moraceae (18 taxa), Dipterocarpaceae (17 taxa), and Rubiaceae (15 taxa). The next five important tree families that occur in the study trails include Theaceae, Guttiferae, Apocynaceae, Leguminosae, and Hypericaceae, with a number of taxa ranging from 10 to 13. Twelve families recorded the number of taxa between 5 and 9, and the remaining 40 families with the range of 1–4 taxa (Fig. 19.7).

19.3.3.2 Tree Communities in the Riparian Forests of Mount Ledang

Riparian forests are narrow, ribbon-like corridors that occur adjacent to many streams (Baker et al. 2002). The ecological structure and function of riparian forests and the associated streams are profoundly intertwined. According to Damasceno-Junior et al. (2005), variations in topography, landform, and soils in riparian forests have strong effects on species composition, distribution, and structure. Near the park rangers’ office of Mount Ledang National Park are riparian forests that harbor some interesting plant life. The river flows down through rocky mountain and many cascades at different heights which created many small pools. Smaller trees and treelets that are especially common in the moist areas include Ixora sp., Rennellia elliptica, Canthium didymium (Rubiaceae), Barringtonia macrostachya (Lecythidaceae), Baccaurea parviflora (Phyllanthaceae), and Microcos latifolia (Tiliaceae). Besides these, Saraca multiflora (Leguminosae) was frequent and easy to identify by its purple young leaves hanging from the ends of the branchlets.

Tree species from Dipterocarpaceae (i.e., Shorea multiflora), Moraceae (i.e., Artocarpus elasticus), Sapotaceae (i.e., Palaquium obovatum), and Leguminosae (i.e., Sindora coriacea and Dialium platysepalum) are big trees encountered on farther away from the stream. Dillenia reticulata (Dilleniaceae) can be identified from its big obovate leaves and stilt roots. Other medium-sized tree species found include Knema scortechinii (Myristicaceae), Diospyros styraformis (Ebenaceae), and Ixonanthes reticulata (Ixonantaceae). Knema is distinguished by its red sap produced from the stem from a slight incision made on the bark, whereas Diospyros by its distinctive black bark, and Ixonanthes by its bole which often fluted. In the openings or gaps of the stream banks, it is not usual to find pioneer species from Euphorbiaceae (i.e., Croton argyratus, Croton laevifolius, and Macaranga sp.).

19.3.3.3 Lowland, Hill, and Upper Hill Dipterocarp Forests

The expedition trail and its elevation profile for the journey to the peak of Mount Ledang are presented in Figs. 19.3 and 19.8, respectively. The exploration began from the lowland dipterocarp forest zone at 257 m altitude. As the name implies, the Dipterocarpaceae are mainly lowland rainforest trees. Trees from this family are the most important timber in Malaysia. A number of Dipterocarpus and Shorea were found in this area. These include Dipterocarpus crinitus, Dipterocarpus cornutus, Dipterocarpus kerrii, and Dipterocarpus kunstleri. Five species of Shorea encountered along the trails were Shorea leprosula, Shorea macroptera, Shorea parvifolia, Shorea pauciflora, and Shorea ovalis. Other dipterocarps found within this elevation include Anisoptera curtisii. Trees from Dipterocarpaceae can be identified from the barks which usually produce resins. Other emergent trees from non-dipterocarp group found in this area include Koompassia malaccensis (Leguminosae), Ochanostachys amentacea (Olacaceae), and Dyera costulata (Apocynaceae).

Small and medium-sized trees that are common in this area include Cinnamomum iners (Lauraceae), Gardenia tubifera (Rubiaceae), Gnetum gnemon (Gnetaceae), Memecylon cantleyi (Melastomaceae), and Pimeleodendron griffithianum (Euphorbiaceae). Cinnamomum can be identified by its aromatic smell from the inner bark and its trinerved leaf characters. Other than timber trees, many other groups of plants contribute to the complexity of the lowland dipterocarp forests. For example, a variety of bamboo, rattans, and palms are especially common as well as climbers and epiphytes.

Different tree communities occurred in the higher elevation along the trail to the peak of Mount Ledang. In the hill dipterocarp forests, Shorea platyclados (Dipterocarpaceae) is common. Tree non-dipterocarp species such as Cratoxylum formosum (Hypericaceae), Syzygium filifrome (Myrtaceae), Calophyllum sp. (Guttiferae), and Gluta wallichii (Anacardiaceae) grow occasionally in this zone. Cratoxylum is distinctive from its iodine-colored sap from the inner bark and its prickly stem. Syzygium can be indentified from its simple opposite leaf arrangement and jambu smell characters, whereas Calophyllum also from its simple and opposite leaf arrangement but with parallel secondary veins. Meanwhile, Gluta can be distinguished from other trees by its black sap from the inner bark.

In the open sites of hill dipterocarp forest, some pioneer species such as Macaranga gigantea, Macaranga triloba, Sapium baccatum, Endospermum diadenum (all from Euphorbiaceae), and Cratoxylum cochinchinense (Hypericaceae) are common. Together with these secondary species, a number of medium-sized non-dipterocarp trees such as Lithorcarpus sp. (Fagaceae), Scaphium macropodum (Sterculiaceae), and Artocarpus scortechinii (Moraceae) were encountered along the hill dipterocarp forests.

Within the upper hill dipterocarp forest, tree species of Shorea (Dipterocarpaceae) are very common big trees along the trails. These include Shorea curtisii and Shorea exelliptica. Shorea curtisii is a typical member of upper hill forest habitat, specifically in valleys of the hill. It is a large emergent tree with a straight and fissured bole. Together with these emergent dipterocarps are a number of non-dipterocarp trees such as Gynotroches axillaris (Rhizophoraceae), Elaeocarpus floribundus (Elaeocarpaceae), and Tristaniopsis razakiana (Myrtaceae). Tristaniopsis is distinctive in terms of its peeling barks with mixed reddish brown to gray-white hues. Smaller trees occasionally encountered along the upper hill trails include Randia scortechinii, Timonius wallichianus (Rubiaceae), Scutinanthe brunnea (Burseraceae), and Gynotroches axillaris (Rhizophoraceae).

19.3.3.4 Lower Montane Forest

During the expedition, lower montane forest was observed before the peak of trails with the presence of lower montane vegetation (e.g., Ploiarium alternifolium—Bonnetiaceae) at 1018 m altitude. At this altitude, dipterocarps and other common lowland families such as Leguminosae, Euphorbiaceae, and Myristiceae begin to diminish and are replaced by a diversity of species from tree families such as Myrtaceae and Theaceae At this elevation, Baeckea frutescens, Leptospermum flavescens (Myrtaceae), and Eurya nitida (Theaceae) form the main tree association. At 1030 m altitude, the forest is mossy and is characterized with low-statured vegetation and devoid of emergent trees.

19.3.3.5 Upper Montane Forest

The upper montane zone occurs on area of telecommunication tower at the end of the trail (1190 m altitude) which is among the highest peaks in Mount Ledang. Within the zone, trees from the family of Podocarpaceae are very common montane taxa such as Podocarpus neriifolius, Dacrydium elatum, and Dacrydium beccarii. They are also much encountered along the trails before the summit. Together with these communities are Magnolia montana (Magnoliaceae), Ardisia retinervia (Myrcinaceae), and Mastixia retinervia (Cornaceae) which distinctly common around the summit zone. This elevation zone also supports a large variety of pitcher (Nepenthacaeae) and ginger (Zingiberaceae) plants. Other montane taxa such as Clerodendrum sp. (Lamiaceae), Schima wallichii (Theaceae), Leptospermum flavescens (Myrtaceae), as well as Ficus cf. sinuata (Moraceae) also occur.

19.3.4 Maesa fraseriana: A Potential New Record for Mount Ledang

Maesa fraseriana, belonging to Maesaceae, is a small shrub (up to 2 m tall) or woody climbers (up to 7 m tall) that is endemic to montane forest of Fraser’s Hill (Fig. 19.9). Utteridge (2012) reported that this species is known from five localities based on ten collections. All collection was from Fraser’s Hill except for a single outlier from Ulu Klang. However, according to Utteridge (2012), it is possible that Maesa fraseriana is found within the central range of Peninsular Malaysia with an extent of occurrence of the collection within 1000 km2. Due to the evidence of habitat decline in Fraser’s Hill, this species was assigned a rating of Endangered B1 ab (iii).

It is interesting to note that, during this expedition, this taxon was found at the moist forest edge (1048 m altitude) near the roadside of plateau base camp, together with other montane taxa such as Dacrydium elatum, Eurya nitida, and Podocarpus neriifolius. Identification of this species was made possible from a consultation with Forest Research Institute Malaysia’s (FRIM’s) herbarium personnel and a thorough literature review. According to Kiew (1992), as compared to lowland forests, endemic species in montane forest may only be confined to a single mountain peak or group of peaks in which in this expedition, this phenomenon is illustrated by the discovery of Maesa fraseriana. In contrast, the geological distribution for the species in the lowland forests is wider. Therefore, the discovery of a new record from the montane forest may have profound implications of conservation as disturbance in the small habitat could affect the survival of the species.

19.3.5 Other Species of Interest

Mount Gunung is an interesting area in terms of geographical variation, species composition, and conservation potential. It shelters species that are endemics and endangered not to the area but also from other parts of Malaysia. The IUCN Red List data were used to provide the information on the conservation status of the listed tree species collected from this survey. In terms of conservation status, among all trees documented, Anisoptera curtisii and Dipterocarpus cornutus are assigned as Critically Endangered (IUCN 2013). The other four species from the family of Dipterocarpaceae, viz, Shorea leprosula, Shorea platyclados, Shorea pauciflora, and Dipterocarpus kerrii, are reported to be endangered (Appendix 1) which may require a combination of sound research and some conservation attention.

19.4 Conclusion

Imbak Canyon and Mount Ledang cover a diverse range of landscape elements and natural vegetation communities from streamside vegetation, lowland, hill, and upper hill mixed dipterocarps up to lower montane heath forests. While information from this survey may provide reference for ecologically useful species as well as species of special concern, sufficiently large-range surveys are still required to gather more comprehensive information to identify conservation efforts for sustainability of forest biodiversity. The areas are likely to harbor a significant number of endemic species; however, the data collected from this expedition were inadequate to document comprehensive information on species richness, endemism, and checklists of rare and endangered species for the area. While information from this survey may provide reference for ecologically useful species as well as species of special concern, follow-up plant inventories are necessary to assess the conservation importance of a particular species.

References

Ashton PS (2004) Dipterocarpaceae. In: Soepadmo E, Saw LG, Chung RCK (eds) Tree flora of Sabah and Sarawak, vol 5. Sabah Forestry Department, Forest Research Institute Malaysia and Sarawak Forestry Department, Malaysia, pp 65–388

Baker JR, Ringold PL, Bollman M (2002) Patterns of tree dominance in coniferous riparian forests. For Ecol Manage 166:311–329

Beaman JH, Beaman RS (1990) Diversity and patterns in the flora of Mount Kinabalu. In Baasetal Dordecht P (ed) The plant diversity of Malesia. Kluwer Academic, Netherlands, pp 147–160

Damasceno-Junior GA, Semir J, Santos FAMD, Leitȃo-Filho HF (2005) Structure, distribution of species and inundation in a riparian forest of Rio Paraguai, Pantanal, Brazil. Flora 200:119–135

IUCN (2011) The IUCN red list of threatened species. Web page, available at http://www.iucnredlist.org/amazing-species. Accessed 4 June 2011

IUCN (2013) The IUCN red list of threatened species. Web page, available at http://www.iucnredlist.org/amazing-species. Accessed 27 Aug 2013

Kiew R (1992) The montane flora of peninsular Malaysia: threats and conservation. Background paper, Malaysian national conservation strategy. Economic Planning Unit, Kuala Lumpur

Latiff A, Mohd Shaffea L (2011) Introduction. In: Benom G (ed) Krau wildlife reserve geology, biodiversity and socio-economic environment. Academy of Science Malaysia and Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Malaysia, pp ix–xii

Sabah Forestry Department (2005) Preferred check-list of Sabah trees, 93 pp

Soepadmo E, Wong KM (eds) (1995) Tree flora of Sabah and Sarawak, vol 1. Sabah Forestry Department, Forest Research Institute Malaysia and Sarawak Forestry Department, Malaysia

van Stennis CGGJ (1984) Floristic altitude zones in Malesia. Bot J Linn Soc 89:289–291

Symington CF (2004) Foresters’ manual of dipterocarps. In Ashton PS, Appanah S (Revised by), Barlow HS (ed), 2nd edn. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, 519 pp

Utteridge TMA (2012) Four new species of Maesa Forssk. (Primulaceae) from Malesia. Kew Bull 67(3):367–378

Whitmore TC (1984) Tropical rain forests of the far east, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 352 pp

Whitmore TC (1998) An introduction to tropical rain forests, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York

de Wilde WJJO (2000) Myristicaceae. In: Soepadmo E, Saw LG (eds) Tree flora of Sabah and Sarawak, vol 5. Sabah Forestry Department, Forest Research Institute Malaysia and Sarawak Forestry Department, Malaysia, pp 335–474

Wyatt-Smith J (1963) Lower montane and upper montane forest. In manual of Malayan silviculture for inland forests. Malay For Records 23, vol II, Chap. 7:23–24

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix 1: List of Trees in Alphabetical Order Documented for the Imbak Canyon and Mount Ledang, Malaysia

Appendix 1: List of Trees in Alphabetical Order Documented for the Imbak Canyon and Mount Ledang, Malaysia

No. | Scientific name | Local name | Family | IUCN Status/remarks | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | Acronychia porteri | Rutaceae | Lower risk/least concern | ML/IC | |

2 | Acronychia sp. | Rutaceae | IC | ||

3 | Actinodaphne montana | Medang paying | Lauraceae | Lower risk/least concern/endemic | IC |

4 | Actinodaphne pruinosa | Medang payung gunung/Medang serai | Lauraceae | Lower risk/least concern | IC/ML |

5 | Actinodaphne sp. | Medang serai | Lauraceae | IC | |

6 | Adinandra dumosa | Tetiup | Theaceae | ML | |

7 | Adinandra maculosa | Bawing | Theaceae | IC | |

8 | Aglaia eximia | Bekak | Meliaceae | ML | |

9 | Aglaia sp. | Bekak | Meliaceae | ML | |

10 | Agrostistachys longifolia | Jenjulong | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

11 | Alstonia angustiloba | Pulai/Pulai bukit | Apocynaceae | IC/ML | |

12 | Alstonia macrophylla | Pulai penipu bukit | Apocynaceae | ML | |

13 | Anaxagorea javanica | Bunga pompun | Annonaceae | ML | |

14 | Anisoptera cutisii | Mersawa durian | Dipterocarpaceae | Critically endangered | ML |

15 | Aporusa microstachya | Phyllanthaceae | ML | ||

16 | Aquilaria malaccensis | Gaharu | Thymelaeaceae | Vulnerable | IC |

17 | Ardisia retinervia | Myrcinaceae | ML | ||

18 | Ardisia sp. | Serusop | Myrsinaceae | IC/ML | |

19 | Arthrophyllum diversifolium | Terentang | Araliaceae | ML | |

20 | Artocarpus anisophyllus | Terap ikal | Moraceae | IC | |

21 | Artocarpus dadah | Tampang | Moraceae | ML | |

22 | Artocarpus elasticus | Terap nasi | Moraceae | IC/ML | |

23 | Artocarpus heterophyllus | KeML tampng bulu | Moraceae | ML | |

24 | Artocarpus lanceifolius | KeML tampng bulu | Moraceae | ML | |

25 | Artocarpus scortechinii | Terap hitam | Moraceae | ML | |

26 | Arytera littoralis | Sapindaceae | ML | ||

27 | Austrobuxus nitidus | Picrodendraceae | ML | ||

28 | Baccaurea parviflora | Kunau-kunau/Rambai hutan/Setambun taik | Euphorbiaceae | IC/ML | |

29 | Baeckea frutescens | Chuchor atap | Myrtaceae | ML | |

30 | Barringtonia macrostachya | Putat | Lecythidaceae | ML | |

31 | Bouea oppositifolia | Kudang daun kecil | Anacardiaceae | ML | |

32 | Brackenridgea palustris | Mata ketam | Ochnaceae | Lower risk/near threatened | ML |

33 | Breynia sp. | Phyllanthaceae | ML | ||

34 | Brownlowia peltata | Pinggau-pinggau | Tiliaceae | IC | |

35 | Buchanania sessifolia | Otak udang daun tajam | Anacardiaceae | ML | |

36 | Callerya atropurpurea | Tulang dalang | Leguminosae | ML | |

37 | Calophylllum tetrapterum | Bintangor | Guttiferae | Lower risk/least concern | IC |

38 | Calophyllum sp. | Bintangor | Guttiferae | ML | |

39 | Calophyllum depresinervosum | Bintangor | Guttiferae | IC | |

40 | Calophyllum dioscurii | Bintangor | Guttiferae | IC | |

41 | Calophyllum macrocarpum | Bintangor | Guttiferae | ML | |

42 | Calophyllum nodosum | Bintangor | Guttiferae | IC | |

43 | Calophyllum obliquinevium | Bintangor | Guttiferae | IC | |

44 | Calophyllum sp. 1 | Bintangor | Guttiferae | IC | |

45 | Calophyllum sp. 2 | Bintangor | Guttiferae | IC | |

46 | Calophyllum wallichianum var wallichianum | Bintangor | Guttiferae | IC | |

47 | Camnosperma auriculatum | Terentang daun besar | Anacardiaceae | IC/ML | |

48 | Campnosperma squamatum | Terentang daun kecil | Anacardiaceae | IC | |

49 | Canarium denticulatum | Kedondong | Burseraceae | IC | |

50 | Canarium littorale | Kedondong gergaji | Burseraceae | Lower risk/least concern | IC/ML |

51 | Canarium pilosum | Kendondong | Burseraceae | IC | |

52 | Canthium didymum | Rubiaceae | ML | ||

53 | Carallia brachiata | Meransi | Rhizophoraceae | ML | |

54 | Casearia clarkei | Flacourtiaceae | IC | ||

55 | Castanopsis megacarpa | Beranggang gajah/getek tangga | Fagaceae | ML | |

56 | Castanopsis sp. | Gertik tangga | Fagaceae | ML | |

57 | Chisochiton ceramicus | Berindu | Meliaceae | IC | |

58 | Cinnamomum iners | Kayumanis/Medang teja | Lauraceae | IC/ML | |

59 | Cinnamomum javanicum | Kayu manis | Lauraceae | IC | |

60 | Cinnamomum sp. | Medang | Lauraceae | IC | |

61 | Clerodendrum sp. | Lamiaceae | ML | ||

62 | Clerodendrum villosum | Lamiaceae | ML | ||

63 | Cratoxylum cochinchinense | Geronggang | Hypericaceae | Lower risk/least concern | ML |

64 | Cratoxylum formosum | Geronggang derum | Hypericaceae | Lower risk/least concern | ML |

65 | Cratoxylum sp. | Geronggang | Hypericaceae | ML | |

66 | Croton argyratus | Hujan panas | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

67 | Croton laevifolius | Hujan panas | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

68 | Croton sp. | Hujan panas | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

69 | Crotoxylum formosum | Geronggang | Hypericaceae | Lower risk/least concern | ML |

70 | Cryptocarya ferrea | Medang | Lauraceae | IC | |

71 | Cyathocalyx pruniferus | Annonaceae | ML | ||

72 | Dacrydium beccarii | Ekor tupai | Podocarpaceae | Least concern | ML |

73 | Dacrydium comosum | Ekor | Podocarpaceae | Endangered | IC |

74 | Dacrydium elatum | Ekor kuda | Podocarpaceae | Lower risk/least concern | ML |

75 | Dacryodes rostrata | Kedondong kerut | Burseraceae | Lower risk/least concern | ML |

76 | Dacryodes rubiginosa | Kedondong | Burseraceae | IC | |

77 | Desmos chinensis | Pisang monyet | Annonaceae | IC | |

78 | Dialium platysepalum | Keranji kuning besar | Leguminosae | ML | |

79 | Dillenia borneensis | Simpoh gajah | Dilleniaceae | IC | |

80 | Dillenia excelsa | Simpoh laki | Dilleniaceae | IC | |

81 | Dillenia reticulata | Simpoh gajah | Dilleniaceae | ML | |

82 | Diospyros andamanica | Kayu arang | Ebanaceae | ML | |

83 | Diospyros buxifolia | Meribut | Ebanaceae | ML | |

84 | Diospyros rigida | Kayu arang | Ebanaceae | ML | |

85 | Diospyros sp. | Kayu arang | Ebanaceae | IC/ML | |

86 | Diospyros styraformis | Kayu arang | Ebanaceae | ML | |

87 | Diospyros wallichii | Kayu malam | Ebanaceae | IC | |

88 | Dipterocarpus sp. | Keruing | Dipterocarpaceae | ML | |

89 | Dipterocarpus caudiferus | Keruing putih | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

90 | Dipterocarpus crinitus | Keruing mempelas | Dipterocarpaceae | ML | |

91 | Dipterocarpus grandiflorus | Keruing belimbing | Dipterocarpaceae | Critically endangered | IC |

92 | Dipterocarpus kerrii | Keruing gondola | Dipterocarpaceae | Endangered | ML |

93 | Dipterocarpus kunstleri | Keruing rapak | Dipterocarpaceae | Critically endangered/near streams | IC |

94 | Dracaena sp. | Asparagaceae | ML | ||

95 | Dryobalanops lanceolata | Kapur paji | Dipterocarpaceae | Endangered/Endemic | IC |

96 | Duabanga moluccana | Megas | Sonneratiaceae | Wet area | IC |

97 | Durio griffithii | Durian kuning | Bombacaceae | IC | |

98 | Durio oxleyanus | Durian | Bombacaceae | IC | |

99 | Dyera costulata | Jelutong/Jelutong bukit | Apocynaceae | Lower risk/least concern | IC/ML |

100 | Dysoxylon sp. | Olop-olop | Meliaceae | IC | |

101 | Elaeocarpus floribundus | Mendung | Elaeocarpaceae | ML | |

102 | Elaeocarpus nitidus var. nitidus | Mendung | Elaeocarpaceae | ML | |

103 | Elaeocarpus palembanicus | Mendung | Elaeocarpaceae | ML | |

104 | Elaeocarpus sp. | Mendung | Elaeocarpaceae | ML | |

105 | Elateriospermum tapos | Perah | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

106 | Endospermum diadenum | Sesenduk | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

107 | Erythroxylum cuneatum | Erythroxylaceae | ML | ||

108 | Eucalyptus deglupta | Kayu putih | Myrtaceae | ML | |

109 | Eurya nitida | Podo kebal musang | Theaceae | ML | |

110 | Eurycoma longifolia | Pahit-pahit | Simaroubaceae | IC | |

111 | Fagraea crenulata | Tembusu | Loganiaceae | ML | |

112 | Falcatifolium falciforme | Podo | Podocarpaceae | Lower risk/least concern | IC |

113 | Ficussp. | Ara | Moraceae | IC/ML | |

114 | Ficus cf. sinuata | Ara | Moraceae | ML | |

115 | Ficus deltoidea | Mas cotek | Moraceae | ML | |

116 | Ficus fulva | Ara | Moraceae | ML | |

117 | Ficus glossularioides | Ara | Moraceae | ML | |

118 | Ficus vasculosa | Kayu ara | Moraceae | IC | |

119 | Ficus xylophylla | Ara | Moraceae | ML | |

120 | Fordia curtisii | Leguminosae | IC | ||

121 | Fordia sp. | Leguminosae | IC | ||

122 | Garcinia malaccensis | Manggis hutan/Kandis | Guttiferae | IC/ML | |

123 | Garcinia sp. | Kandis | Guttiferae | IC/ML | |

124 | Gardenia tubifera | Mentiong bukit | Rubiaceae | ML | |

125 | Gironniera subaequalis | Ampas tebu/Hampas tebu | Ulmaceae | IC/ML | |

126 | Glochidion borneensis | Ubah nasi | Euphorbiaceae | IC | |

127 | Glochidion superbum | Gerumong jantan | Euphorbiaceae | IC | |

128 | Gluta aptera | Rengas/Rengas kerbau jalang | Apocynaceae | IC/ML | |

129 | Gluta elegans | Rengas | Apocynaceae | ML | |

130 | Gluta wallichii | Rengas | Apocynaceae | ML | |

131 | Gnetum gnemon | Meninjau | Gnetaceae | Least concern | ML |

132 | Gonocaryum gracile | Icacinaceae | ML | ||

133 | Gordonia concentricicatrix | Semak pulut | Theaceae | ML | |

134 | Gordonia sp. | Samak pulut | Theaceae | ML | |

135 | Gymnacranthera forbesii | Lanau | Myristicaceae | IC | |

136 | Gynotroches axillaris | Rhizophoraceae | ML | ||

137 | Helicia sp. | Proteaceae | IC | ||

138 | Heritiera elata | Kembang | Sterculiaceae | IC | |

139 | Heritiera javanica | Kembang | Sterculiaceae | IC | |

140 | Homalium longifolium | Telur buaya | Sterculiaceae | Lower risk/least concern | ML |

141 | Hopea nervosa | Selangan jangkang | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

142 | Hopea sp. 1 | Selangan | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

143 | Hopea sp. 2 | Selangan | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

144 | Hopea vesquei | Selangan bukit karangas | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

145 | Horsfieldia guatteriifolia | Darah-darah | Myristicaceae | IC | |

146 | Horsfieldia polyspherula | Darah-darah | Myristicaceae | IC | |

147 | Horsfieldia sp. | Darah-darah | Myristicaceae | IC | |

148 | Ilex cymosa | Mensirah | Aquifoliaceae | ML | |

149 | Ilex macrophylla | Mensirah | Aquifoliaceae | ML | |

150 | Ilex sp. | Mensirah | Aquifoliaceae | ML | |

151 | Ilex triflora | Mensirah | Aquifoliaceae | ML | |

152 | Irvingia malayana | Pauh kijang | Irvingiaceae | Lower risk/least concern | IC |

153 | Ixonanthes icosandra | Pagar anak | Ixonanthaceae | ML | |

154 | Ixonanthes reticulata | Inggir burung | Ixonanthaceae | ML | |

155 | Ixora sp. | Kiam/Jejarum | Rubiaceae | IC/ML | |

156 | Ixora sp. | Kiam | Rubiaceae | IC | |

157 | Knema laurina | Darah-darah | Myristicaceae | IC | |

158 | Knema malayana | Darah-darah | Myristicaceae | Lower risk/least concern | IC |

159 | Knema patentinervia | Penarahan | Myristicaceae | ML | |

160 | Knema scortechinii | Penarahan | Myristicaceae | ML | |

161 | Knema stenophylla subsp. longipedicellate | Darah darah | Myristicaceae | Endemic | IC |

162 | Koilodepas longifolium | Euphorbiaceae | ML | ||

163 | Kokoona reflexa | Mata ulat | Celastraceae | ML | |

164 | Koompasia malaccensis | Kempas | Leguminosae | Lower risk/conservation dependent | ML |

165 | Koompassia excelsa | Mengaris | Leguminosae | Lower risk/conservation dependent | IC |

166 | Lasianthus sp. | Rubiaceae | IC | ||

167 | Leea indica | Mali-mali | Leeaceae | IC | |

168 | Leptospermum flavescens | Cina maki | Myrtaceae | ML | |

169 | Leucostegane latistipulata | Mempisang | Leguminosae | Vulnerable | IC |

170 | Lindera montanoides | Medang pawas | Lauraceae | IC | |

171 | Lithocarpus curtisii | Mempening | Fagaceae | Vulnerable | IC |

172 | Lithocarpus encleiscarpus | Mempening | Fagaceae | IC | |

173 | Lithocarpus ewyckii | Mempening | Fagaceae | IC | |

174 | Lithocarpus sp. | Mempening | Fagaceae | ML | |

175 | Lithocarpus wallichianus | Mempening | Fagaceae | ML | |

176 | Litsea sp. | Medang | Lauraceae | ML | |

177 | Lophopetalum sp. | Mata ulat | Celastraceae | ML | |

178 | Macaranga gigantea | Mahang gajah | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

179 | Macaranga hypoleuca | Sedaman putih/Mahang kapur | Euphorbiaceae | IC/ML | |

180 | Macaranga laciniata | Mahang | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

181 | Macaranga triloba | Sedaman/Mahang merah | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

182 | Maclurodendron porteri | Rutaceae | ML | ||

183 | Maesa fraseriana | Maesaceae | New record for Mount Ledang | ML | |

184 | Magnolia montana | Magnoliaceae | ML | ||

185 | Magnolia sp. 2 | Cempaka | Magnoliaceae | IC | |

186 | Mallotus griffithianus | Balik angin | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

187 | Mallotus macrostachyus | Balik angin | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

188 | Mallotus oblongifolius | Balik angin | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

189 | Mallotus sp. | Balik angin | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

190 | Mallotus stipularis | Mallotus | Euphorbiaceae | IC | |

191 | Mangifera griffthii | Rawa | Anacardiaceae | ML | |

192 | Maranthes corymbosa | Merbatu | Chrysobalanaceae | ML | |

193 | Mastixia pentandra | Tetebu | Cornaceae | ML | |

194 | Melastoma malabatricum | Senduduk | Melastomataceae | ML | |

195 | Memecylon amplexicaule | Nipis kulit | Melastomataceae | ML | |

196 | Memecylon cantleyi | Nipis kulit | Melastomataceae | ML | |

197 | Memecylon minutiflorum | Nipis kulit | Melastomataceae | ML | |

198 | Memecylon pubescens | Nipis kulit | Melastomataceae | ML | |

199 | Memecylon sp. | Nipis kulit | Melastomataceae | ML | |

200 | Mesua kochummeniana | Penaga bayan | Guttiferae | ML | |

201 | Mesua racemosa | Penaga | Guttiferae | ML | |

202 | Mesua sp. | Penaga | Guttiferae | ML | |

203 | Mezzettia leptopoda | Mempisang | Annonaceae | IC/ML | |

204 | Microcos antidesmifolia | Kerodong | Tiliaceae | IC | |

205 | Microcos latifolia | Chenderai | Tiliacea | ML | |

206 | Microcos sp. | Tiliacea | ML | ||

207 | Monocarpia marginalis | Mempisang | Annonaceae | ML | |

208 | Myrica esculenta | Myricaceae | ML | ||

209 | Nauclea albicinales | Rubiaceae | ML | ||

210 | Nauclea sp. | Rubiaceae | ML | ||

211 | Nauclea subdita | Bangkal kuning | Rubiaceae | IC | |

212 | Neesia sp. | Durian monyet | Bombacaceae | IC | |

213 | Norrisia malaccensis | Loganiaceae | ML | ||

214 | Ochanostachys amentacea | Tanggal/Petaling | Olacaceae | IC/ML | |

215 | Octomeles sumatrana | Benuang | Datiscaceae | Lower risk/least concern | IC |

216 | Oxyspora sp. | Melastomaceae | IC | ||

217 | Palaquium maingayi | Nyatoh durian | Apocynaceae | ML | |

218 | Palaquium obovatum | Nyatoh | Apocynaceae | ML | |

219 | Pangium edule | Kepayang | Salicaceae | ML | |

220 | Parashorea melaanonan | Urat mata daun licin | Dipterocarpaceae | Critically endangered | IC |

221 | Parashorea tomentella | Urat mata beludu | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

222 | Parinari elmeri | Merbatu | Chrysobalanaceae | ML | |

223 | Parinari oblongifolia | Merbatu | Chrysobalanaceae | IC | |

224 | Parkia javanica | Kupang/Petai kerayong | Leguminosae | IC/ML | |

225 | Parkia speciosa | Petai kerayong | Leguminosae | ML | |

226 | Payena lucida | Nyatoh | Sapotaceae | ML | |

227 | Payena maingayi | Nyatoh | Sapotaceae | Lower risk/least concern | IC |

228 | Pentace laxiflora | Takalis daun halus | Tiliaceae | IC | |

229 | Phyllocladus sp. | Podocarpaceae | IC | ||

230 | Pimeleodendron griffithianum | Perah ikan | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

231 | Pinus carribea | Pine | Pinaceae | ML | |

232 | Pittosporum ferrugineum | Pitosporaceae | ML | ||

233 | Ploiarium alternifolium | Riang riang | Bonnetiaceae | ML | |

234 | Ploiarium sp. | Riang riang | Bonnetiaceae | ML | |

235 | Podocarpus neriifolius | Podo bukit | Podocarpaceae | Least concern | ML |

236 | Podocarpus neriifolius | Kayu china | Podocarpaceae | Lower risk/least concern | IC |

237 | Polyalthia clauliflora | Kerai larak | Annonaceae | IC | |

238 | Polyalthia rumphii | Mempisang | Anonaceae | ML | |

239 | Polyalthia sumatrana | Mempisang | Anonaceae | ML | |

240 | Popowia pisocarpa | Mempisang | Annonaceae | ML | |

241 | Porterandia anisophylla | Tinjau belukar | Rubiaceae | ML | |

242 | Pouteria malaccensis | Nyatoh nangka kuning | Sapotaceae | ML | |

243 | Premna corymbosa | Leban | Verbanaceae | ML | |

244 | Prunus sp.1 | Pepijat | Rosaceae | ML | |

245 | Prunus sp.2 | Stone fruits | Rosaceae | ML | |

246 | Pternandra coerulescens | Sial menahun | Melastomataceae | ML | |

247 | Pternandra echinata | Sial menahun | Melastomataceae | ML | |

248 | Pterospermum javanicum | Bayur bukit | Malvaceae | ML | |

249 | Pterospermum sp. | Bayor | Sterculiaceae | IC | |

250 | Randia scortechinii | Tinjau belukar | Rubiaceae | ML | |

251 | Rapanea porteriana | Myrcinaceae | ML | ||

252 | Rennellia elliptica | Tepejat | Rubiaceae | ML | |

253 | Rennellia speciosa | Rubiaceae | IC | ||

254 | Rhodamnia cinerea | Mempoyan/poyan | Myrtaceae | ML | |

255 | Rinorea anguifera | Sentil tembakau | Violaceae | ML | |

256 | Santiria griffithii | Kedondong | Burseraceae | ML | |

257 | Santiria laevigata | Kerantai/Kedondong kerantai lichin | Burseraceae | Lower risk/least concern | IC/ML |

258 | Santiria tomentosa | Kerantai bulu | Burseraceae | Lower risk/least concern | IC |

259 | Sapium beccatum | Ludai | Euphorbiaceae | ML | |

260 | Saprosma sp. | Rubiaceae | ML | ||

261 | Saraca cauliflora | Gapis | Leguminosae | ML | |

262 | Sarcotheca griffithii | Belimbing pipi | Oxalidaceae | ML | |

263 | Scaphium linearicarpum | Kembang semangkok bulat | Sterculiaceae | ML | |

264 | Scaphium macropodum | Kembang semangkok jantung | Sterculiaceae | Lower risk/least concern | IC/ML |

265 | Schefflera sp. | Araliceae | IC | ||

266 | Schima wallichii | Gegatal | Theaceae | ML | |

267 | Schoutenia accrescens | Bayur bukit | Tiliacea | ML | |

268 | Scorodocarpus borneensis | Bawang hutan | Olacaceae | IC | |

269 | Scutinanthe brunnea | Kedondong sengkuang | Burseraceae | Lower risk/least concern | ML |

270 | Shorea agentifolia | Seraya daun emas | Dipterocarpaceae | Endangered | IC |

271 | Shorea atrinervosa | Selangan batu hitam | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

272 | Shorea ciliata | Dipterocarpaceae | Endangered | IC | |

273 | Shorea curtisii | Meranti seraya | Dipterocarpaceae | Lower risk/least concern | ML |

274 | Shorea excelliptica | Balau tembaga | Dipterocarpaceae | ML | |

275 | Shorea fallax | Seraya daun kasar | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

276 | Shorea flaviflora | Seraya daun besar | Dipterocarpaceae | Critically endangered | IC |

277 | Shorea guiso | Selangan batu merah | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

278 | Shorea johorensis | Seraya majau | Dipterocarpaceae | Critically endangered | IC |

279 | Shorea laevis | Selangan batu kumus | Dipterocarpaceae | Lower risk/least concern/ridges | IC |

280 | Shorea leprosula | Seraya tembaga/Meranti tembaga | Dipterocarpaceae | Endangered | IC/ML |

281 | Shorea macroptera | Meranti melantai | Dipterocarpaceae | ML | |

282 | Shorea Maxwelliana | Selangan batu asam | Dipterocarpaceae | Endangered | IC |

283 | Shorea microphylla | Kawang jantung | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

284 | Shorea monticola | Seraya gunung | Dipterocarpaceae | Endemic, mountains | IC |

285 | Shorea multiflora | Damar hitam pipit | Dipterocarpaceae | ML | |

286 | Shorea obscura | Dipterocarpaceae | Hills | IC | |

287 | Shorea ovalis | Meranti kepong | Dipterocarpaceae | ML | |

288 | Shorea ovata | Seraya punai bukit | Dipterocarpaceae | Endangered | IC |

289 | Shorea parvifolia | Meranti sarang punai | Dipterocarpaceae | ML | |

290 | Shorea parvifolia | Seraya punai | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

291 | Shorea parvistipulata | Seraya lupa | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

292 | Shorea patoiensis | Seraya kuning pinang | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

293 | Shorea pauciflora | Meranti nemesu | Dipterocarpaceae | Endangered | ML |

294 | Shorea platyclados | Meranti bukit | Dipterocarpaceae | Endangered | ML |

295 | Shorea sp. | Seraya/Meranti | Dipterocarpaceae | IC/ML | |

296 | Sindora beccariana | Sepetir | Leguminosae | IC | |

297 | Sindora coriacea | Sepetir lichin | Leguminosae | ML | |

298 | Sindora echinocalyx | Sepetir daun nipis | Leguminosae | IC | |

299 | Sloanea javanica | Mendong | Lauraceae | IC | |

300 | Stemonurus malaccensis | Katok | Icacinaceae | IC | |

301 | Sterculia parvifolia | Kelumpang | Sterculiaceae | ML | |

302 | Streblus elongatus | Tempinis | Moraceae | ML | |

303 | Swintonia sp. | Merpauh | Anacardiaceae | ML | |

304 | Symplocos adenophylla | Symplocaceae | ML | ||

305 | Symplocos sp. | Symplocaceae | ML | ||

306 | Syzygium filiforme | Kelat | Myrtaceae | ML | |

307 | Syzygium griffithii | Kelat | Myrtaceae | ML | |

308 | Syzygium politum | Kelat | Myrtaceae | ML | |

309 | Syzygium pustulatum | Kelat | Myrtaceae | ML | |

310 | Syzygium sp. 1 | Kelat serai | Myrtaceae | ML | |

311 | Syzygium sp. 1 | Obah | Myrtaceae | IC | |

312 | Syzygium sp. 2 | Kelat | Myrtaceae | ML | |

313 | Syzygium sp. 3 | Obah | Myrtaceae | IC | |

314 | Syzygium sp. 4 | Obah | Myrtaceae | IC | |

315 | Syzygium sp. 5 | Kelat | Myrtaceae | ML | |

316 | Syzygium stapfianum | Obah | Myrtaceae | IC | |

317 | Syzygium subdesugata | Kelat | Myrtaceae | ML | |

318 | Tarenna sp. | Rubiaceae | ML | ||

319 | Terminalia sp. | Telisai | Combretaceae | IC | |

320 | Ternstroemia tectandra | Langkubak | Theaceae | IC | |

321 | Timonius wallichianus | Kaum kopi | Rubiaceae | ML | |

322 | Trigonostemon malaccanus | Euphorbiaceae | ML | ||

323 | Tristaniopsis merguensis | Pelawan | Myrtaceae | ML | |

324 | Tristaniopsis razakiana | Pelawan | Myrtaceae | ML | |

325 | Tristaniopsis whiteana | Pelawan | Myrtaceae | IC | |

326 | Urophyllum sp. | Rubiaceae | ML | ||

327 | Vatica dulitensis | Resak bukit | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

328 | Vatica maingayi | Resak daun merah | Dipterocarpaceae | Critically endangered | IC |

329 | Vatica sp. | Resak | Dipterocarpaceae | IC | |

330 | Vitex longisepala | Leban | Verbanaceae | ML | |

331 | Vitex pinnata | Leban | Verbanaceae | ML | |

332 | Vitex pubescence | Leban | Verbanaceae | ML | |

333 | Vitex sp. 1 | Kulimpapa | Verbenaceae | IC | |

334 | Vitex sp. 2 | Kulimpapa | Verbenaceae | IC | |

335 | Weinmannia fraxinea | Cunoniaceae | ML | ||

336 | Xanthophyllum affine | Minyak berok | Polygalaceae | IC | |

337 | Xanthophyllum eurhynchum | Minyak berok | Polygalaceae | ML | |

338 | Xanthophyllum sp. | Minyak berok | Polygalaceae | IC/ML | |

339 | Xerospermum noronhianum | Rambutan pacat | Polygalaceae | ML | |

340 | Xylopia sp. | Jangkang | Annonaceae | ML |

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Suratman, M., Hamid, N., Sabri, M., Kusin, M., Yamani, S. (2015). Changes in Tree Species Distribution Along Altitudinal Gradients of Montane Forests in Malaysia. In: Öztürk, M., Hakeem, K., Faridah-Hanum, I., Efe, R. (eds) Climate Change Impacts on High-Altitude Ecosystems. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12859-7_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12859-7_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-12858-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-12859-7

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)