Abstract

The paper has proposed a theory of structural focus which analyzes focus movement as the establishment of a syntactic predicate–subject structure, expressing specificational predication. The subject of the specificational construction, an open sentence, determines a set, which the predicate (the focus-moved constituent) identifies referentially. The subject of predication is associated with an existential presupposition (only an existing set can be referentially identified). The referential identification of a set consists in the exhaustive listing of its members—hence the exhaustivity of focus. It is claimed that this analysis also accounts for properties of focus movement constructions that current alternative theories cannot explain.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

Mikkelsen (2004) argues that the predicate of a specificational construction is, nevertheless, more referential than its subject.

- 4.

Although in subsequent stages of the derivation, Q-raising and topicalization can remove certain constituents of the postfocus unit (the subject of predication), they remain represented by their copies in postverbal position.

- 5.

NNP stands for Non-Neutral Phrase; it is a term of Olsvay (2000).

- 6.

- 7.

According to Geurts and van der Sandt (2004), the background is associated with an existential presupposition in all types of focus constructions. They call the following rule ‘the null hypothesis’

(i) The Background-Presupposition Rule

Whenever focusing gives rise to a background λx.φ(x), there is a presupposition to the effect that λx.φ(x) holds of some individual.

- 8.

Delin and Oberlander (1995) make a similar claim about the subordinate clause of cleft sentences: they count as presuppositional also when they convey information that is expected to be known.

- 9.

The English equivalents of (7b) and (16b) are called comment-clause clefts by Delin and Oberlander (1995).

- 10.

Puskas (2000:342) claims that this does not hold in Hungarian, on the basis of examples like.

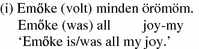

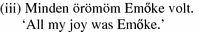

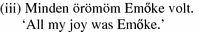

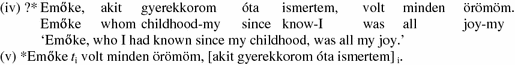

According to Surányi (2002), the constraint formulated by Giannakidou and Quer (1995) does not apply to all-type universal quantifiers. However, in Hungarian, every and all-type quantifiers do not seem to differ in the relevant respect (neither of them can be focussed). In my analysis, Emőke is the predicate nominal in (i), and minden örömem is the subject. If minden örömem were a predicate nominal, it ought to be able to precede the verb volt (occupying first Spec, PredP, and then Q-raised into a PredP-adjoined position). Furthermore, if Emőke were the subject, it ought to be able to undergo topicalization, i.e., to occupy an unstressed clause-initial position. Both of these moves are impossible

According to Surányi (2002), the constraint formulated by Giannakidou and Quer (1995) does not apply to all-type universal quantifiers. However, in Hungarian, every and all-type quantifiers do not seem to differ in the relevant respect (neither of them can be focussed). In my analysis, Emőke is the predicate nominal in (i), and minden örömem is the subject. If minden örömem were a predicate nominal, it ought to be able to precede the verb volt (occupying first Spec, PredP, and then Q-raised into a PredP-adjoined position). Furthermore, if Emőke were the subject, it ought to be able to undergo topicalization, i.e., to occupy an unstressed clause-initial position. Both of these moves are impossible Cf.

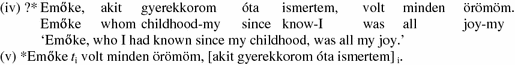

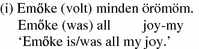

Cf.  A reviewer mentions that if Emőke is the predicate of this sentence, it will reject a nonrestrictive relative clause. This is, indeed, the case:

A reviewer mentions that if Emőke is the predicate of this sentence, it will reject a nonrestrictive relative clause. This is, indeed, the case: The reviewer also mentions that in the English She is my every dream, where the quantifier occurs inside (rather than on the edge of) the predicate nominal, the noun phrase my every dream is not outwardly quantificational: Someone made my every dream come true does not support a distributive reading. This does not hold for Hungarian; in example (vi), the noun phrase is Q-raised, and is interpreted distributively

The reviewer also mentions that in the English She is my every dream, where the quantifier occurs inside (rather than on the edge of) the predicate nominal, the noun phrase my every dream is not outwardly quantificational: Someone made my every dream come true does not support a distributive reading. This does not hold for Hungarian; in example (vi), the noun phrase is Q-raised, and is interpreted distributively

- 11.

In fact, a semantically incorporated theme or goal argument occupying Spec, PredP, the position of secondary predicates, can be represented by a bare nominal.

- 12.

Hungarian verbs of (coming into) being and creation also have particle verb counterparts, which denote the change of their theme, whose existence is presupposed. These particle verbs, as opposed to their bare V equivalents, select a [+specific] theme

References

Behaghel, Otto. 1932. Deutsche Syntax IV. Heidelberg: Carl Winters.

Delin, Judy J., Jon, Oberlander. 1995. Syntactic constraints on discourse structure: the case of it-clefts. Linguistics 33/3.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 1995. Definiteness effect revisited. In: Levels and structures. Approaches to Hungarian, ed. István Kenesei, Vol. 5, 65–88. Szeged: JATE.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 1998. Identificational focus versus information focus. Language 74: 245–273.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 2006a. Apparent or real? On the complementary distribution of identificational focus and the verbal particle. In: Event structure and the left periphery. Studies on Hungarian, ed. É. Kiss, Katalin, 201–224. Dordrecht: Springer.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 2006. Focussing as predication. In The architecture of focus, ed. Valéria Molnár, and Susanne Winkler, 169–193. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 2008. Free word order, (non–)configurationality, and phases. Linguistic Inquiry 39: 441–475.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 2009. Structural focus and exhanstivity. In Information structure: theoretical, typological, and experimental perspectives, ed. Caroline Féry, and Malte Zimmermann. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fanselow, Gisbert. 2006. On pure syntax. In Form, structure and grammar, ed. P. Brandt, and E. Fuss. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Geurts, Bart, and Rob Sandt. 2004. Interpreting focus. Theoretical Linguistics 30: 1–44.

Higgins, Roger F. 1973. The pseudo-cleft construction in English. PhD diss., MIT

Horn, Laurence R. 1972. On the semantic properties of logical operators in English. Ph.D. diss., UCLA

Horvath, Julia. 2005. Is “Focus Movement” driven by stress? In: Approaches to Hungarian 9. Papers from the Düsseldorf Conference, eds. Christopher Piñón and Péter Siptár, 131–158. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Horvath, Julia. 2006. Separating “Focus Movement” from focus. In Clever and Right: A Festschrift for Joe Emonds, ed. V.S.S. Karimi, et al. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Huber, Stefan. 2000. Es-Clefts und det-Clefts. Stockholm: Almquist and Wiksell.

Kadmon, N. 2001. Formal pragmatics. Oxford: Blackwell.

Levinson, S.C. 2000. Presumptive meanings. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mikkelsen, Line H. L. 2004. Specifying who: on the structure, meaning, and use of specificational copular clauses. PhD diss., University of California Santa Cruz

Olsvay, Csaba. 2000. Formális jegyek egyeztetése a magyar nemsemleges mondatokban. In A mai magyar nyelv leírásának újabb módszerei IV, ed. László Büky, and Márta Maleczki, 119–151. Szeged: SZTE.

Partee, Barbara. 1987. Noun phrase interpretation and type-shifting principles. In: Studies in discourse representation theory and the theory of generalized quantifiers, GRASS 8, eds. J. Groenendijk, D. de Jongh, and M. Stokhof, 115–143. Dordrecht: Foris

Peredy, Márta. 2009. Obligatory adjuncts licensing definiteness effect constructions. In: Adverbs and adverbial adjuncts at the interfaces, ed. Katalin É. Kiss, 197–230. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter

Piñón, Christopher. 2006a. Definiteness effect verbs. In: Event structure and the left periphery, ed. Katalin É. Kiss, 75–90. Dordrecht: Springer

Piñón, Christopher. 2006b. Weak and strong accomplishments. In: Event structure and the left periphery, ed. Katalin É. Kiss, 91–106. Dordrecht: Springer

Puskás, Genovéva. 2000. Word order in Hungarian: the syntax of A–bar positions. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1995. Interface strategies. OTS Working Papers (TL-95-002).

Surányi, Balázs. 2002. Multiple operator movements in Hungarian. Utrecht: LOT.

Szabolcsi, Anna. l981. The semantics of topic–focus articulation. In: Formal methods in the study of language, eds. J. Groenendijk et al., 513–540. Amsterdam: Matematisch Centrum.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1986. From the definiteness effect to lexical integrity. In Topic, focus, and configurationality, ed. Werner Abraham, and Sjaak de Meij, 321–348. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Szendrői, Kriszta. 2003. A stress-based approach to the syntax of Hungarian focus. The Linguistic Review 20: 37–78.

Wedgwood, Daniel. 2005. Shifting the focus. From static structures to the dynamics of interpretation. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Zubizarreta, Maria. 1998. Prosody, focus, and word order. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kiss, K.É. (2017). Deriving the Properties of Structural Focus. In: Lee, C., Kiefer, F., Krifka, M. (eds) Contrastiveness in Information Structure, Alternatives and Scalar Implicatures. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, vol 91. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10106-4_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10106-4_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-10105-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-10106-4

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)

According to Surányi (

According to Surányi ( Cf.

Cf.  A reviewer mentions that if Emőke is the predicate of this sentence, it will reject a nonrestrictive relative clause. This is, indeed, the case:

A reviewer mentions that if Emőke is the predicate of this sentence, it will reject a nonrestrictive relative clause. This is, indeed, the case: The reviewer also mentions that in the English She is my every dream, where the quantifier occurs inside (rather than on the edge of) the predicate nominal, the noun phrase my every dream is not outwardly quantificational: Someone made my every dream come true does not support a distributive reading. This does not hold for Hungarian; in example (vi), the noun phrase is Q-raised, and is interpreted distributively

The reviewer also mentions that in the English She is my every dream, where the quantifier occurs inside (rather than on the edge of) the predicate nominal, the noun phrase my every dream is not outwardly quantificational: Someone made my every dream come true does not support a distributive reading. This does not hold for Hungarian; in example (vi), the noun phrase is Q-raised, and is interpreted distributively