Abstract

Organizational transformation is a complex and multifaceted process that involves a fundamental change in the way an organization operates and delivers value to its stakeholders. It can be triggered by a variety of internal and external forces, such as technological change, shifts in the competitive landscape, or changes in market demand. To successfully manage organizational change, organizations must be able to adapt and respond to changing circumstances in a proactive and strategic manner. This chapter reviews important concepts and theories of organizational change from the perspective of management research and examines selected theories and frameworks that have been developed to understand and manage organizational change. Overall, this chapter provides insights and lessons for practitioners and researchers alike. It aims to help readers understand the complexities and challenges of organizational transformation, but also to provide an overview of strategies and approaches to successfully navigate a transformation process.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Keywords

- Organizational transformation

- Effectuation

- Institutional theory

- Change management

- Digital transformation

1 Organizational Change and Transformation

Organizational transformation refers to the process of fundamentally changing the way an organization operates and delivers value to its stakeholders, and may require major changes in the way work is done. It may involve changes to the organization’s structure, culture, business processes, governance, and/or external relationships. There are many reasons why an organization may undergo a transformation. For example, it may seek to respond to a rapidly changing market, new technological opportunities, changing regulatory requirements, or changing norms and expectations in the society in which the organization operates. Consider, for example, the current rise of Generative Artificial Intelligence. Transformer language models (BART, ChatGPT), AI that generates software code (Copilot), or AI that generates images of all kinds (Midjourney, Dall-E) require profound changes not only in higher education institutions, but also in companies of all kinds, for example, in the way marketing copy is written (Peres et al. 2023), in the way innovation processes are organized (Piller et al. 2023), but also in the way job applications are processed. More generally, the rapid growth of available data combined with better machine learning algorithms is changing the way management decisions are made, how operational processes can be automated, and leading to the emergence of entirely new business models. Generative AI thus contributes to the overall demand for digital transformation—the process of using digital technologies to fundamentally change the way an organization operates and delivers value to its stakeholders (Vial 2019; Nambisan et al. 2019). At the same time, digitization is also enabling new ways of working that address individuals’ changing preferences for their workplace and work processes. In parallel with this ongoing digital transformation, organizations need to sustainably transform all aspects of their current business models into new, future-proof approaches. As discussed in more detail in other chapters of this book, the mandate for companies to respond to the threat of climate change and related sustainability challenges is probably the biggest driver of organizational transformation today. Overall, we are truly living in “transformational times” (Gruber 2023).

Regardless of its trigger, organizational transformation seeks to make an organization better able to compete effectively in a changing competitive environment (Newman 2000). A related but often distinct concept is organizational change, which refers to any change in an organization’s structure, processes, or practices (Hage 1999; Weick and Quinn 1999). It can range from small, incremental changes to more significant shifts in the way the organization operates. In general, the term organizational transformation is used to refer to a broader and more far-reaching process than organizational change. Organizational transformation typically involves a deeper level of change and has a greater impact on the organization and its stakeholders. Organizational change, on the other hand, may be more focused and limited in scope and may have a more modest impact on the organization.

Previous research has addressed this difference by distinguishing between first-order and second-order change (Newman 2000). According to Meyer et al. (1993), first-order change refers to changes that involve incremental adjustments to an organization’s existing structures, processes, and practices, but do not involve fundamental changes in strategy, core values, or corporate identity (Dutton and Dukerich 1991; Fox-Wolfgramm et al. 1998). These changes are often modest in scope and impact and do not fundamentally alter the way the organization operates. Examples of first-order change include the implementation of new technologies or processes, or the reorganization of existing work teams. First-order change is most likely to occur during periods of relative environmental stability and is likely to occur over extended periods of time (e.g., Tushman and Romanelli 1985). It improves the fit and consistency between an organization and its competitive and institutional contexts, but does not produce fundamental change.

Second-order change, on the other hand, refers to more fundamental and transformative changes that involve a significant shift in the way the organization operates. These changes are often broader and more far-reaching in their impact. Examples of second-order change include the introduction of new business models, the adoption of new technologies that fundamentally change the way the organization operates, or the introduction of new governance structures. Second-order change “takes organizations out of their familiar domains and alters the bases of power” (William 1983: 99). It is a strategic reorientation, an organizational metamorphosis (Meyer et al. 1993), or a change in organizational templates or archetypes (Greenwood and Hinings 1996). Paradoxically, the more adapted firms are to their competitive and institutional context, i.e., the better they are at implementing first-order change, the more difficult it is for them to achieve second-order change (Granovetter 1985; Greenwood and Hinings 1996). Strategies for balancing these two poles have thus become a central topic in contemporary management research (for example, the extensive literature on organizational ambidexterity, e.g., O’Reilly and Tushman 2008; Raisch and Birkinshaw 2008, but also the recent emphasis on paradox theory, e.g., Carmine and Smith 2020; Lewis 2000; Moschko et al. 2023).

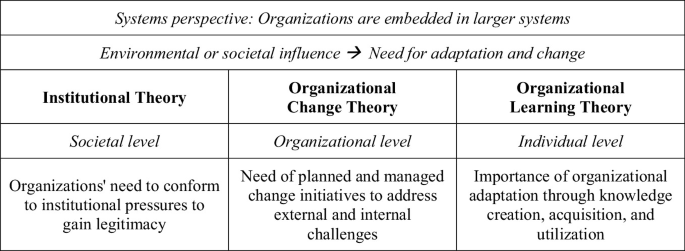

In the management literature, three theoretical perspectives for studying organizational transformation (second-order change) can be distinguished (Newman 2000): institutional theory, organizational change theory, and organizational learning theory. We will briefly review these broad schools in Sect. 2. This prepares Sect. 3, where we review selected concepts that have been widely used in previous management research to explain and manage organizational change. In Sect. 4, we then provide a deep dive into a transformation domain that has received a lot of attention in management research over the last decade, namely digital transformation. This focus may serve as an illustration of the theories and approaches described before. We conclude with a brief reflection and outlook in Sect. 5.

2 Three Classic Theories to Study Organizational Transformation

Newman (2000) highlights three theoretical perspectives for studying organizational transformation (second-order change): institutional theory, organizational change theory, and organizational learning theory. These three theories are closely related and overlapping. Their level of analysis can serve as a simplified distinction (Fig. 1): While institutional theory argues at the level of a society (industry), work using organizational change theory is predominantly located at the level of the organization (business unit). Organizational learning emphasizes the role of individuals in an organization where learning ultimately takes place.

Institutional theory is a framework for understanding how organizations conform to societal norms and expectations (DiMaggio and Powell 1983; Greenwood and Hinings 1996; Meyer and Rowan 1977; Zucker 1987). It is based on the idea that organizations are influenced by a set of institutional forces arising from the social, political, and economic context in which they operate, and that they adopt certain practices and behaviors in order to gain legitimacy and fit into the broader institutional environment. When these societal norms, which include laws, regulations, professional standards, and cultural norms, change (suddenly), organizations must change as well. Thus, institutional theory is often used to understand how organizations adapt to and shape the institutional environment in which they operate, and how they navigate the tensions and trade-offs that can arise between competing institutional logics. This term refers to the underlying values and assumptions that guide organizational behavior and shape the way organizations understand and interact with their environment (Alford and Friedland 1985). Finally, institutional work refers to the actions that organizations take to align their practices and behaviors with institutional expectations and norms (Zietsma and Lawrence 2010). This may involve conforming to existing norms or creating new ones in order to gain acceptance and legitimacy.

Organizational change theory examines the process of change within organizations, which in the context of this chapter can be understood as a process of institutional work to achieve second-order change (Armenakis and Bedeian 1999; Beer and Walton 1987). It is concerned with understanding how and why organizations change, as well as the factors that influence the change process (Meyer et al. 1993; Tushman and Romanelli 1985). Some of the key issues commonly addressed in organizational change theory include leadership, resistance to change, communication, power dynamics, and the role of culture in the change process. Accordingly, a number of frameworks have been developed to explain and understand the process of organizational change. While taking different perspectives, most of these frameworks build on the same few key ideas. Change is seen as a continuous process, a constant and ongoing process rather than a one-time event. This means that organizations must be able to adapt and respond to changing circumstances in order to remain relevant and successful—a perspective that refers to first-order change rather than transformation (Tushman and Romanelli 1985). Organizational change can involve both technical and social aspects. Technical change may involve the adoption of new technologies or processes, while social change may involve changes in the way people work together or interact with each other. Much of the change literature emphasizes the importance of considering these aspects together when implementing change (Hanelt et al. 2021). Effective change often requires strong leadership to guide and direct the process. This may include providing a clear vision for the change, communicating the benefits of the change to stakeholders, and building support for the change (Konopik et al. 2021; Eisenbach et al. 1999). Leadership is also needed because change can be difficult. Changing the way an organization operates can be a challenging process, and it is not uncommon for people to resist or be resistant to change. Understanding and managing this resistance is an important aspect of the change process (Kotter 1995).

Finally, organizational learning theory focuses on how organizations acquire, process, and apply new knowledge and information to adapt and improve. It is based on the idea that organizations are open systems that interact with their environment and can learn from their experiences (Levitt and March 1988; Schulz 2002). Organizational learning refers to the process by which organizations, and especially the individuals who make up that organization, acquire, process, and apply new knowledge and information in order to adapt and improve (Schulz 2002). Organizational learning can take many forms, such as learning from past experiences, learning from the experiences of others (e.g., through collaboration or benchmarking), or learning from new technologies or processes. It involves the integration and application of new knowledge and information in ways that help the organization adapt and improve. Organizational learning is an ongoing process that takes place throughout the life of the organization, continuously adapting and improving based on new information and experience. As a broad field of study, there are a variety of different approaches to organizational learning, each with its own unique perspective on how organizations learn and how that learning can be facilitated. But again, most approaches share some key ideas, including the perspective of learning as a social process. Organizational learning involves the interaction and communication of individuals within the organization. It is not just an individual process, but rather a collective process involving the sharing and integration of knowledge and ideas (Levitt and March 1988). Therefore, learning is influenced by the culture of the organization: An organization’s culture plays a significant role in shaping its capacity to learn. A culture that values learning and encourages experimentation and risk-taking is more likely to facilitate learning than a culture that is resistant to change (Cook and Yanow 2011). At the same time, learning is contextual. The specific context in which learning takes place can have a significant impact on the process and outcomes of learning. Finally, organizational learning requires reflective practices, i.e., the deliberate and systematic examination of one’s own experiences and actions. It allows organizations to critically evaluate their experiences and identify opportunities for improvement.

Overall, institutional theory, organizational change theory, and organizational learning theory are complementary perspectives that try to explain how firms respond to change: Institutional theory focuses on the influence of external change and pressures on organizations. Organizational change theory then explains how organizations react to external influences by adapting their existing structures. Lastly, organizational learning describes how organizations learn from past failure and success and thus have the ability to apply this knowledge on upcoming situations, in which organizations need to rethink their existing structures and strategies in order to successfully perform change.

3 Selected Concepts and Frameworks Supporting Organizational Transformation

In this section, we complement the general theoretical overview from the last section by reviewing three streams of literature that we believe provide representative insights into different theoretical approaches in management research to studying change at the organizational level: dynamic capabilities, effective decision making, and transformational leadership. As noted in the introduction, the prior literature often does not distinguish between first-order and second-order change. However, we are confident that the following selection of concrete approaches can contribute to a holistic understanding of transformation research.

The three concepts selected for review in this section have been widely used in previous management research to explain and manage organizational change. We acknowledge that our choice of these concepts is our own and rather subjective. We have tried to cover different aspects of management research that can provide the readers of this interdisciplinary book—which is primarily aimed at an audience beyond the field of management and economics—with a “representative” introduction to how previous research in our field (management research) has investigated the broad field of “transformation.” We have tried to select three complementary perspectives: Dynamic capabilities added the notion of second-order change to the strategic management literature. Their level of analysis is the firm or business unit. Effectuation, on the other hand, is a relatively new concept that originated in the entrepreneurship literature to explain change and transformation in start-ups. It has only recently been transferred to the context of managing change in established organizations. Its level of analysis is the way entrepreneurs and managers (teams) deal with uncertainty and use transformations in their environment as a driver for change. Transformational leadership, finally, recognizes the importance of leadership behavior as a facilitator of organizational change and transformation and takes an individual-level perspective of a company’s top leaders.

3.1 Dynamic Capabilities

Firms are constantly in the process of adapting, reconfiguring, and recreating their organizational resources and capabilities in order to remain competitive (Wang and Ahmed 2007). In this context, the notion of dynamic capabilities has been widely explored in the strategic management literature. Dynamic capabilities refer to “organizational and strategic routines by which firms achieve new resource configurations as markets emerge, collide, divide, evolve, and die” (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000: 1107). Conceptually, they extend the established resource-based view (RBV) of the firm, a theoretical framework that explains how competitive advantage is achieved within a firm and sustained over time (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). The RBV views an organization as a set of resources. These resources are heterogeneously distributed across firms. Resource differences between firms persist over time and can explain differences in competitive advantage across firms (Amit and Schoemaker 1993). While the RBV has been seen as a key addition to the previously dominant market-based view of the firm (Porter 1980) and has received much general agreement and attention in the management literature, a key criticism of the RBV has been that it is based on the assumption that the market is static and does not address dynamic developments (Teece et al. 1997; Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). The traditional set of resources captured by the RBV explains when and why a firm can gain competitive advantage due to its unique set of capabilities among a set of given competitors in a market. But the traditional RBV could not explain how firms compete in dynamic markets, how and why certain firms have competitive advantage in unstable environments and situations of unpredictable change. In the seminal paper introducing the idea of dynamic capabilities, Teece et al. (1997) argue that in dynamic markets where the competitive landscape is changing, a different set of resources and capabilities forms the source of sustainable competitive advantage, dynamic capabilities.

Conceptually, dynamic capabilities are organizational and strategic routines that allow firms to effectively sense and shape their environment in order to pursue new opportunities and respond to changing circumstances (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). These capabilities include the ability to continuously learn, adapt, and innovate to create and exploit new sources of value (Grant 1996; Teece and Pisano 1994). Dynamic capabilities include both the creation and use of resources, such as knowledge, skills and organizational structures, and the processes by which these resources are managed and mobilized (Teece et al. 1997). They include the ability to reconfigure and redeploy resources in response to changing environments and opportunities, and to build new capabilities as needed. Teece (2007) describes the development of dynamic capabilities as an unfolding process of sensing, harnessing, and reconfiguring firm resources. This conceptualization of dynamic capabilities suggests that firms should have the capacity for the process to first sense and shape opportunities and threats, second seize opportunities, and third maintain competitiveness by enhancing, combining, protecting, and, when necessary, reconfiguring the firm’s intangible and tangible assets (Teece 2007).

The sensing mechanism identifies customers with unmet needs and develops technological opportunities. The capabilities required are therefore threefold. Before directing innovation efforts, organizations must identify target market segments and customer needs, and they must be able to assess developments in the business ecosystem. Organizations also need to harness internal innovation and manage internal innovation processes. Accordingly, external sources of innovation must also be tapped, which are suppliers and complements, exogenous science, and customer engagement in open innovation (Teece 2007; Schoemaker et al. 2018).

Seizing capabilities refer to the ability to mobilize resources, address needs, and exploit business opportunities to create value and mitigate risk for the organization. Seizing capabilities pay special attention to the value of partnerships, realigning the boundaries of the firm and integrating these concepts into the business model (Teece 2007, 2014). With the integration of external partners and information sources, the need for decision-making protocols emerges. The organization must also determine the boundaries within which it operates. This includes decisions about the design of alliances to develop capabilities, as well as the management of integration, in- and outsourcing, and the value of co-specialization within the value network, all while protecting intellectual property and designing an organizational culture for innovation (Teece 2007, 2014).

The final building block, transforming or reconfiguring capabilities, refers to the continuous recombination and reconfiguration of resources and structures under changing environments to support business models (Teece 2007). This mechanism highlights the need for organizations to continuously renew their resource base. Effective management of internal and external resources, as well as knowledge management, enables effective and continuous realignment of resources (Teece 2007, 2014). To be successful, top management teams must possess entrepreneurial skills to adapt to and influence an ever-changing business environment. Effective decision making and transformational leadership, which will be explored in the next sections of this chapter, can be seen as constituting such entrepreneurial capabilities.

Overall, dynamic capabilities are a key factor in a firm’s ability to compete and succeed in today’s rapidly changing business environment. Empirical research on dynamic capabilities has mostly examined the relationship between a firm’s dynamic capabilities and firm performance. It is generally supported that all three mechanisms of dynamic capabilities, namely sensing, seizing, and transforming, have an effect on the firm’s long-term success (Rindova and Kotha 2001; Torres et al. 2018). They enable firms to continuously learn, adapt, and innovate to create and exploit new sources of value. We believe that the core idea of dynamic capabilities can also be applied to the higher level of transformation research as conceptualized in this book. Future interdisciplinary research needs to apply the concept of dynamic capabilities to higher level domains where transformation takes place: an industry, a region, a society—or the world.

3.2 Effectual Decision Making

While dynamic capabilities is a theory that developed in the context of strategic management in established organizations, another theory that can contribute to the study and management of organizational change is effectuation (Sarasvathy 2001, 2008; Fisher 2012). The term describes a decision-making approach that is particularly relevant in contexts where the future is uncertain and available resources are limited. It involves focusing on the resources and capabilities that are already available and using these resources to actively shape and create opportunities, rather than simply reacting to them. Effectuation involves taking calculated risks, being flexible and adaptable, and building a network of relationships and collaborations (Fisher 2012). Effectuation logic can be applied at different times in a firm’s development depending on what type of change the firm is going through (Ko et al. 2021).

Effectuation is often explained in contrast to causation, the typical decision-making approach traditionally taught in management schools. Causation involves identifying a clear goal or objective and then developing a plan to achieve that goal based on a clear understanding of the causal relationships between different variables (Sarasvathy 2008). Competitive advantage in these models is conceptualized as largely determined by competencies related to the exploitation of opportunities and resources controlled by the organization (Chandler and Jansen 1992).

In a now famous example, Sarasvathy (2008) further explained the dichotomous concepts of effectuation and causation. She suggests the metaphors of a jigsaw puzzle for the causation approach and a patchwork quilt for the effectuation approach. In the puzzle, an entrepreneur’s task is to take an existing market opportunity and use resources to create a competitive advantage. In the puzzle builder’s view, all the pieces are there, but they need to be put together in the right way. In the patchwork quilt approach, the entrepreneur is asked to develop an opportunity by experimenting and incorporating new information as it becomes available. The patchwork quilter sees the world as a changing state shaped by human action (Sarasvathy 2008). Overall, the key difference between effectuation and causation is the level of uncertainty and predictability in the context in which they are used. Causation is more relevant to predictable and stable contexts, while effectuation is more relevant to uncertain and unpredictable contexts-such as those typical of organizational change and transformation. Effectuation assumes that an overall strategic goal is not clear from the outset. Decision-makers use a logic of non-predictive control and focus on “choosing between possible effects that can be created with given means” (Sarasvathy 2008).

Originally developed as a theory to explain the success of serial entrepreneurs, effectuation has received considerable scholarly attention in recent decades (Perry et al. 2012). Its application has been extended far beyond entrepreneurship circles to fields such as creativity and innovation (Blauth et al. 2014), marketing (Coviello and Joseph 2012), and operations and project management (Midler and Silberzahn 2008). Effectuation has also received attention in the field of research and development processes. Brettel et al. (2012) suggest that mobilizing an effectual mode of decision making can positively affect R&D performance, especially when innovativeness is high. Based on this study, Blauth et al. (2014) find that the use of an effectual decision-making logic has a positive impact on practiced creativity, while the use of a causal logic seems to have a negative impact on creativity. These relationships become stronger as the level of uncertainty increases. Nevertheless, recent research suggests that effectuation and causation even complement each other in the pursuit of highly innovative projects (Yusuf and Sloan 2015).

Future research has yet to establish a formal link between effectuation and organizational change. However, both concepts involve the process of adapting and responding to change in order to create value. Organizational transformation often involves significant changes in the way an organization operates, which can be difficult and uncertain. In these situations, an effectuation-based approach can be useful to help the organization focus on the resources and capabilities it already has, and to use those resources to actively shape and create new opportunities in the face of uncertainty. We see great potential for establishing effectual decision making as a core concept for transformation management as understood in the context of this book. However, future research needs to establish the links between these concepts in greater detail.

3.3 Transformational Leadership

While dynamic capabilities explain how a specific set of resources can enable organizations to implement second-order change, and the establishment of an effectual decision-making logic can enable an incumbent organization to cope with the uncertainty typical of organizational change, the final concept discussed in this section as a potentially fruitful framework from management research to establish an interdisciplinary transformation framework is transformational leadership. In recent decades, an increasing number of researchers have recognized the importance of leadership behavior as a facilitator of organizational change and transformation (Higgs and Rowland 2008; Oreg et al. 2011). Our brief review of key concepts in the three foundational theories of managing organizational change, as described in the introduction to this chapter, also pointed to the role of leadership. A wide range of expectations have been proposed for the role of a leader in an organization undergoing change: For example, leaders should act as visionaries, advisors, change agents, or consultants (Felfe 2006). Thus, there is no clear definition of the concept of leadership in past and current research, but rather a variety of definitions. These definitions differ not only in terms of the leader’s role within the organization, but also in terms of various factors such as the characteristics of leadership behavior, the leader’s influence on organizational goals, organizational success, culture, and employee performance and satisfaction (Yukl 1989).

Past research has been consistent in assigning organizational leaders the primary responsibility of directing followers toward the achievement of organizational goals (Zaccaro and Klimoski 2002). A pragmatic definition by Northouse (2021: 24) builds on a core assumption, a leader’s significant influence on followers, and defines leadership as “a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goals.” Leaders are considered to have a broad ability to influence employee performance and well-being (Lok and Crawford 2004). In this regard, studies have shown a relationship between organizational outcomes and different leadership styles (Waldman et al. 2001). This research proposes that leaders exhibit a specific (leadership) style, which is a combination of personal characteristics and behaviors of leaders when interacting with their team members. For example, Bommer et al. (2005) suggest that leaders’ values are reflected in employees’ attitudes toward change. The authors find that leaders’ openness values are negatively related to followers’ intentions to resist organizational change. Higgs and Rowland (2008) argue that group-focused leadership practices and behaviors have a positive impact on change success. Berson and Avolio (2004) find a link between a leader’s style and communication skills and his or her ability to raise the organization’s awareness of organizational change. Thus, there is growing evidence that leadership traits and behaviors influence the success or failure of organizational change (Higgs and Rowland 2008).

Within the literature on leadership styles, the theoretical concept of Bass (1985), which distinguishes between transactional and transformational leadership, deserves recognition in the context of this chapter. Bass’ theoretical model groups the behavioral patterns of supervisors toward their employees into two different dimensions. According to Bass (1985), leadership behavior can first be described by comparing two leadership styles, transformational leadership and transactional leadership. Transformational leadership is characterized by the adaptability of the leader. The leader is able to identify current challenges and respond to them in a timely manner (Bass et al. 2003). It is also characterized by the “transformation” of the values and attitudes of employees and the resulting increase in employee motivation and performance (Felfe 2006; Waldman et al. 2001). Thus, transformational leadership focuses on inspiring and motivating followers to not only achieve their goals, but also to strive for personal and professional growth. Transformational leaders seek to engage followers in a shared vision and empower them to take responsibility for their work and development.

Transformational leadership involves four key components—the “four Is”: idealized influence, intellectual stimulation, intellectual input, and individualized consideration. Idealized influence describes the behavior of transformational leaders who serve as role models and inspire their followers to strive for excellence. They demonstrate integrity, honesty, and authenticity and are able to earn the respect and trust of their followers. This component describes leaders as both professional and moral role models (Felfe 2006). Inspirational motivation proposes that transformational leaders are able to inspire and motivate their followers by articulating a compelling vision and helping them see the purpose and meaning behind their work and the change required. Leaders motivate followers by instilling optimism and enthusiasm for achieving set goals and the organization’s mission and values (Bass et al. 2003). Intellectual stimulation means that leaders encourage their followers to question established tasks, think critically, challenge assumptions, and seek new and creative solutions to problems. Transformational leaders encourage creativity and innovation in their followers (Bass et al. 2003). Finally, individualized consideration suggests that transformational leaders provide individualized support and development to their followers, encouraging them to identify and develop their strengths and potential in a targeted manner. Leaders take on the role of a mentor (Bass et al. 2003). Research has shown that transformational leadership can be effective in a variety of settings and can lead to improved performance, job satisfaction, and commitment among employees (Liu et al. 2010). However, transformational leaders must be authentic and genuine in their interactions with followers, as insincere or manipulative behavior can undermine trust and effectiveness (Felfe 2006).

Transactional leadership, on the other hand, is a leadership style that focuses on establishing clear expectations and rewards for achieving specific goals and objectives. Transactional leaders use a system of rewards and punishments to motivate and direct their followers and provide feedback and guidance to help them achieve their goals. Thus, transactional leadership is characterized by a clearly regulated exchange relationship between leaders and followers (Felfe et al. 2004; Felfe 2006). Transactional leadership has two key components. First, transactional leaders use contingent rewards such as praise, recognition, and tangible incentives to motivate and reward followers for achieving specific goals and objectives (Felfe 2006). Second, transactional leaders engage in management by exception. That is, they use a system of monitoring and feedback to identify and correct deviations from expected standards and performance (Bass et al. 2003).

Transactional leadership can be effective in situations where there is a clear and defined set of goals and tasks, and where there is a need for stability and predictability. However, it may be less effective in situations where there is a need for creativity, innovation, or adaptability. However, when comparing transformational and transactional leadership styles, transformational and transactional leadership should not be seen as opposing behaviors, but can be used simultaneously by leaders depending on the situation (Felfe et al. 2004). Transformational leaders promote a common understanding of strategic goals that align with the organization’s vision. In addition, they create a learning environment that encourages employees to question ways of working in order to translate specific goals into actions. The effectiveness of strategic goal implementation depends on how well leaders in an organization perceive and clarify the goals, translate them into more specific goals tied to the respective units, and then foster an open learning environment to facilitate the pursuit and successful completion of the goals (Felfe et al. 2004). Transactional leaders, on the other hand, as a more instrumental leadership style, provide a concrete platform from which leaders can actively engage with followers in implementing change. The reinforcing and rewarding nature of transactional leadership would underpin specific engagement behaviors, such as providing information that emphasizes personal impact. Thus, transformational and transactional leadership styles are thought to be complementary, albeit situational, during organizational change (Tushman and Nadler 1986).

Overall, the theoretical concepts of transformational leadership and organizational transformation are strongly related. Transformational leaders are able to inspire and motivate their followers to embrace change and strive for excellence, and to build the skills and resources needed to successfully manage organizational transformation. As a result, they play a critical role in driving and managing organizational transformation efforts.

4 Digital Transformation

Digital transformation is challenging executives across industries (Correani et al. 2020). Most recently, COVID-19 urged leaders to rethink existing internal systems and move toward digital transformation, recognizing the strategic importance of technology in their organizations. Current research has not reached a consensus on what exactly digital transformation is (Warner and Wäger 2019). Despite the lack of an explicit definition, digital transformation is always associated with organizational change: Organizations need to adapt to the general expansion of digital technologies—defined as the combination and interconnection of myriad, distributed information, communication, and computing technologies (Bharadwaj et al. 2013). Thus, digital transformation can be linked to the organizational change initiated by the proliferation of digital technologies (Hanelt et al. 2021).

Digital transformation refers to the process of using digital technologies to fundamentally change the way an organization operates and delivers value to its stakeholders (Vial 2019; Nambisan et al. 2019). It involves the integration of digital technologies into all areas of the organization, including its business models, processes, and operations, to enable new forms of value creation and improve performance (Hanelt et al. 2021). The core proposition is that digital technologies enable new forms of value creation. Digital technologies, such as the Internet, mobile devices, and artificial intelligence, enable organizations to create new forms of value that were not previously possible. For example, they can be used to improve customer experiences, create new products and services, or streamline operations. These technologies also have the potential to disrupt traditional business models and create new opportunities for organizations (Hinings et al. 2018). They can enable organizations to reach new markets, create new revenue streams, and challenge established players in their industry. In this section, we use the domain of digital transformation as an example to review the state of research in the management discipline on organizational transformation.

Prior research has established that digital transformation requires a holistic approach (e.g., Appio et al. 2021; Hanelt et al. 2021; Vial 2019). Digital transformation is not just about implementing new technologies, but rather about fundamentally rethinking and changing the way an organization operates. It requires a holistic approach that considers the impact of digital technologies on all aspects of the organization. This often involves a change in the culture of the organization, as it requires a different way of thinking and working. It also requires new skills, new ways of collaborating and communicating, and a willingness to embrace change and take risks. Accordingly, the concept of dynamic capabilities has been specified for digitalization, as we will review in the next subsection. Previous research has also derived a number of process models for digital transformation that capture the need for a holistic process. Finally, at the end of this section, we discuss how the state of transformation can be measured by introducing the idea of a digital maturity model—which can be seen as prototypical examples to inspire future research on organizational transformation.

4.1 (Dynamic) Capabilities for Digital Transformation

The emergence of new technologies, and thus new opportunities for organizations, has reshaped business models across industries (Liu et al. 2011). Hence, digital transformation is more complex than just integrating new digital technologies into the existing organizational structure and processes. In this context, the idea of dynamic capabilities has been adapted to the field of digitalization (Konopik et al. 2021), building on the notion in previous research in strategic management that the existence of dynamic capabilities has a positive impact on competitive advantage in dynamic environments (Drnevich and Kriauciunas 2011; Li and Liu 2014). For digital transformation, Warner and Wäger (2019), for example, found that firms need to build a system of dynamic capabilities to be successful in digital transformation. Hanelt et al. (2021) proposed that firms with high levels of dynamic capabilities have higher levels of digital maturity than firms with low levels of dynamic capabilities. In addition, Konopik et al. (2021) state that organizational capabilities relevant to digital transformation are equivalent to the dynamic capability approach of three mechanisms: sensing, seizing, and transforming. Companies rely on a specific set of dynamic capabilities along their digital transformation process, namely strategy and ecosystem formation, innovation thinking, technology management, data management, organizational design, and leadership. We briefly review these aspects in the following.

Capabilities related to strategy and ecosystem formation refer to the adaptation of existing business models during the digital transformation process (Warner and Wäger 2019). They also include the formation and management of ecosystems that span multiple organizations, functions, and industries initiated by digital transformation (Berman and Marshall 2014; Hanelt et al. 2021). The formation and management of digital ecosystems requires the ability to identify the key stakeholders and partners involved in the ecosystem and to establish clear roles, responsibilities, and expectations. This may involve creating governance structures and mechanisms to facilitate collaboration and coordination among stakeholders. Second, it is important to establish the technical infrastructure and platforms that will support the ecosystem, such as cloud computing, data analytics, and API management. Finally, companies need the ability to design business models and revenue streams to support the ecosystem and ensure that the ecosystem’s value proposition creates value for all stakeholders (Matt et al. 2015).

Innovation thinking refers to organizational capabilities that enable the emergence of innovations from within or outside the organization (open innovation). Innovation thinking enables organizations to identify and explore new possibilities, challenge assumptions and existing ways of doing things, and experiment with new ideas. It also involves the ability to think creatively and see problems and challenges from multiple perspectives, which can help generate novel solutions (Hinings et al. 2018). Involving the customer in the innovation processes (co-creation) is a key element here, especially by focusing efforts on improving the customer experience (Elmquist et al. 2009). This also includes the development capacity to enhance products with digital technologies (Warner and Wägner 2019).

Digital Technology Management. Intuitively, digital technologies play a critical role in the digital transformation process. Technology management as a digital transformation capability therefore involves the strategic planning, acquisition, and deployment of technology resources, as well as the ongoing management and optimization of these resources to deliver maximum value. This includes activities such as technology roadmap development, vendor management, and technology portfolio management (Konopik et al. 2021). Effective technology management is a critical capability for digital transformation because it enables organizations to identify and adopt the most appropriate technologies for their needs, integrate these technologies into their operations, and continuously optimize and evolve their technology stack in response to changing business needs and the evolving digital landscape (Besson and Rowe 2012).

Data management refers to organizational capabilities related to the handling, security, and capitalization of data. It is critical to digital transformation because it enables organizations to collect and analyze data from a variety of sources, including internal systems, customer interactions, and external sources. This data can be used to optimize business processes, improve decision making, and identify new opportunities (Haffke et al. 2016). Data management also includes ensuring the quality, integrity, and security of data, as well as the governance and compliance of data-related activities. This is important because organizations rely on accurate and reliable data to make decisions and maintain the trust of their stakeholders. A specific capability discussed in this context is managing the tension between sharing data with third parties, enabling better decisions at the system level, and maintaining competitive advantage at the firm level (Konopik et al. 2021).

Organizational design. The structural and procedural organization must adapt to support digital transformation strategies. Changes may be triggered by new or adapted business models or new technologies (Hess et al. 2016). Effective organizational design is critical to digital transformation because it enables organizations to align their structure, processes, and systems with their strategic goals and objectives and create the conditions for innovation and agility. This may involve redesigning roles and responsibilities, implementing new processes and systems, or introducing new governance structures (Hinings et al. 2018).

Leadership finally involves creating a culture and leadership style that supports digital transformation and encourages collaboration, creativity, and continuous learning. This is important because digital transformation often requires significant changes in the way work is done, and a supportive culture and leadership style can help facilitate these changes (Eisenhardt and Martin 2010; Matt et al. 2015). Interestingly, the leadership construct has been largely neglected in the general dynamic capabilities literature (Schilke et al. 2018). However, an appropriate leadership style is a key requirement for the successful transformation of organizations (Nadkarni and Prügl 2021) and for overcoming internal resistance from various stakeholders during the transformation processes (Matt et al. 2015).

In conclusion, dynamic capabilities are an important consideration for organizations seeking to undertake digital transformation. Dynamic capabilities refer to an organization’s ability to continuously adapt and evolve in response to changing circumstances and opportunities. They include the ability to sense and respond to change, to learn and innovate, and to recombine and leverage resources and capabilities in new ways. Dynamic capabilities help organizations navigate the uncertainty and complexity of digital transformation and continuously adapt and evolve in response to changing circumstances and opportunities. However, developing dynamic capabilities is not easy and requires a significant investment of time and resources. It also requires a culture and leadership style that supports change and continuous learning, and encourages collaboration, creativity, and experimentation.

4.2 Digital Transformation Process Models

A second stream of research has focused on providing frameworks and process models to address the question of how organizations can successfully undertake digital transformation. It is widely recognized that digital transformation is a process consisting of various stages (Hess et al. 2016; von Leipzig et al. 2017; Sebastian et al. 2017). Process models for digital transformation refer to frameworks or approaches that organizations can use to guide their digital transformation efforts. These models typically provide a structured approach for identifying and prioritizing digital opportunities, implementing new technologies and processes, and measuring and tracking progress. This process model perspective is consistent with earlier change management literature, which suggests that transformation is a process that evolves through stages, rather than a short-term response to external events. Among these well-established models, four are particularly noteworthy:

-

Kotter’s eight-step change model outlines a process for leading organizational change that includes creating a sense of urgency, forming a guiding coalition, creating a vision, communicating the vision, empowering others to act on the vision, creating short-term wins, consolidating gains, and embedding new approaches in the organizational culture (Kotter 1995, 1996).

-

Lewin’s change management model is based on the idea that change involves moving from one state (the “unfreeze” stage) to another (the “refreeze” stage) and involves three steps: unfreezing, changing, and refreezing. Unfreezing involves breaking down the existing state and creating a willingness to change. Changing involves implementing the new ideas or processes. Refreezing involves reinforcing the changes and making them the new norm (Lewin 1947).

-

The ADKAR model, developed by Jeff Hiatt (2006), is a goal-oriented change management model that focuses on the individual and helps organizations understand and manage the change process from the individual’s perspective. The model consists of five elements that form the acronym of its name: Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, and Reinforcement.

-

According to the six-step change management model (Beer et al. 1990), change is realized by solving concrete business problems. The first step is to diagnose the specific problem. The definition of the problem situation then helps to create commitment to change. Then, a vision of change is developed that defines new roles and responsibilities. Next, the vision should be properly communicated to stakeholders to gain support and consensus. The change is now implemented and, in a next step, institutionalized with formal systems. Finally, the progress of the change process is monitored and adjustments are made if necessary.

Most change models proposed for digital transformation combine elements of these classic models. For example, Hess et al. (2016) identify four dimensions of a digital transformation framework. These four dimensions are the use of technology, changes in value creation, structural changes, and financing digital transformation. First, the firm should determine a strategy for the use of technology: Companies can either create their own technology standards and become market leaders, or serve and adapt to already established standards. Then, using new technologies means changing the value proposition of the company. Structural changes, i.e., “variations in a firm’s organizational setup” (Hess et al. 2016, p. 341), have to be considered, as digitizing products or services requires a recalculation of the existing business scope, as potentially new customer segments are taken into account. Subsequently, an assessment of whether products, processes, or capabilities are primarily affected by the changes will further determine the scope of the restructuring. Substantial changes may require the creation of a separate division within the company, while limited changes are more likely to require the integration of new activities into the existing company structure. Finally, taking into account these three dimensions of the transformation process, the financial aspects, which are both drivers and constraints of the transformation, are analyzed (Hess et al. 2016). An assessment of all these four dimensions helps companies to formulate a company-specific strategy for digital transformation.

The model proposed by von Leipzig et al. (2017) also focuses on the initial phase of developing a digital strategy as a starting point for digital transformation. Following Deming’s Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle (Deming 1982), it postulates an iterative rather than a linear process for initiating digital transformation. To successfully overcome the challenges of digital transformation, in the first stage, managers should be aware of the need to change their existing business plan by analyzing customers, the market, competitors, as well as other industries, as customers may expect the same level of digital services regardless of the industry (von Leipzig et al. 2017). In the second stage, benchmarks should be used to compare their position with other companies and analyze strengths and weaknesses. In the third stage, an assessment of the costs resulting from selected changes in the business model will then prepare the implementation of the digital strategy. In the fourth stage, feedback mechanisms include customer and employee perceptions and comparisons with peers. With each subsequent iteration, the company should elaborate on the feedback and adjust its capabilities.

Sebastian et al. (2017) propose a process model of digital transformation for large incumbents based on two distinct strategic priorities: a customer engagement strategy and a digital solutions strategy. A customer engagement strategy aims to deliver a superior, innovative, personalized, and integrated customer experience through an omnichannel experience that allows customers to order, inquire, pay, and receive support in a consistent manner from any channel. A digital solutions strategy, on the other hand, is appropriate when the company’s value proposition is reimagined through the integration of products, services, and data. The core of this digital strategy is anticipating customer needs rather than reacting to them. In the first phase of a digital transformation process, companies must therefore make the right assumption about their future by choosing one of the two strategic priorities. The second stage is to build an appropriate operational digital backbone, such as a customer database to access customer data and/or a supply chain management system to provide transactional visibility. The third step is to build a digital services platform, which means setting up APIs to access the necessary data. With the help of IT partners, companies can then build the infrastructure to analyze and support the digital services. In Phase IV, the digital services platform is further deployed, integrating the needs of customers and stakeholders. Finally, in Phase V, a service culture should be instilled from the top down. It is crucial that business and IT teams work together to create and deliver business services, as “designing around business services will become the way most companies do business” (Sebastian et al. 2017).

In summary, process models are an important consideration for organizations seeking to undertake digital transformation. Process models provide a structured approach to guide digital transformation efforts and can help organizations identify and prioritize digital opportunities, implement and scale digital initiatives, and measure and track progress. It is important for organizations to carefully select and tailor a process model that aligns with their specific needs and goals, and to be aware of the limitations and challenges of each model. Process models should also be flexible and adaptable in the face of changing circumstances in order to continuously learn and improve the model as needed.

However, even when following a specific process model for digital transformation, established organizations can fail (Brenk et al. 2019). In a recent study, Moschko et al. (2023) investigate why organizations fail to achieve their initial ambitions for a digital transformation process. They build on the observation that managers often perceive tensions when engaged in a transformation process (Appio et al. 2021; Brenk et al. 2019; Moschko et al. 2013). To examine these tensions, Moschko et al. (2023) turn to paradox theory (Hahn and Knight 2021; Lewis and Smith 2014). Paradoxes are “contradictory yet interrelated elements that exist simultaneously and persist over time” (Smith and Lewis 2011, p. 382). These paradoxes cause actors to experience tensions, “defined as stress, anxiety, discomfort, or tightness in making choices and moving forward in organizational situations” (Putnam et al. 2016, p. 68). For leaders, tensions are problematic trade-offs that need to be resolved or avoided during a change process. Attempts to resolve one of these tensions and paradoxes often create others, resulting in what are known as knotted paradoxes (Smith and Lewis 2022), which can occur at multiple levels—from the individual to the organization to society. As Moschko et al. (2023) show, the notion of (knotted) paradoxes can help managers shift their conceptual frameworks to better understand the complexity and interdependent dynamics of transformation processes. Thus, the development of a paradoxical mindset supports managers in successfully executing a digital transformation process.

4.3 Digital Maturity

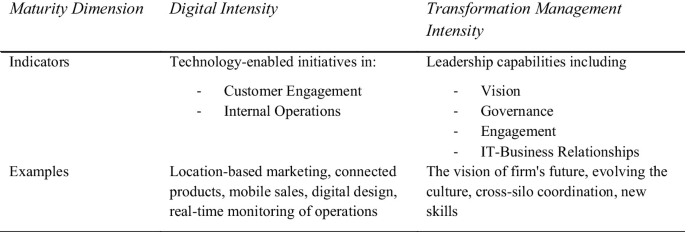

A final concept from the digital transformation discourse is the idea of digital maturity assessments. The term digital maturity refers to “the ability to respond to the environment in an appropriate manner through (digital) management practices” (Bititci 2015). Digital maturity models are frameworks that assess an organization’s current level of digital maturity and provide a roadmap for improving digital capabilities. The models typically distinguish different levels of digital maturity, each representing an increasingly advanced level of digital capabilities. One of the most prominent models was developed by MIT’s Center for Information Systems Research (CISR), based on research into the digital practices of leading companies (Westerman et al. 2011). It differentiates digital maturity into two dimensions, digital intensity and transformation management intensity. Companies that are mature in the digital intensity dimension invest in technology-enabled initiatives with the goal of changing the way the company operates, i.e., customer engagement and internal operations (see Fig. 2). The second dimension, transformation management intensity, addresses the creation of leadership capabilities needed to successfully execute a digital transformation. Transformation intensity involves a strategic vision of the planned digitalization, the necessary governance and commitment, and the relationships with IT and business partners implementing technology-driven change (Westerman et al. 2011).

Digital maturity dimensions (Westerman et al. 2011)

Depending on the level of digital maturity along these two dimensions, the authors differentiate five different maturity stages, each representing a progressively more advanced level of digital capabilities:

-

Level 1: Digital Novice: These are organizations with only limited digital capabilities, focused on automating existing processes.

-

Level 2: Digital Apprentice: At this level, organizations are starting to explore new digital technologies and are beginning to integrate them into their operations.

-

Level 3: Digital Practitioner: These are organizations that have established a strong foundation of digital capabilities and are actively seeking out new digital opportunities.

-

Level 4: Digital Experts are organizations that have fully integrated digital technologies into their operations and are continuously innovating and experimenting with new digital initiatives.

-

Level 5: Digital Leader: At this level, organizations are a leader of digital practices in their industry (“lighthouse sites”) and are driving industry-wide digital transformation.

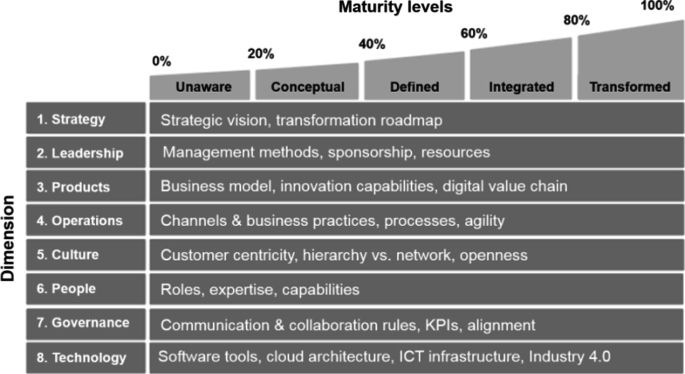

Organizations can use a digital maturity model to assess their current level of digital maturity, identify areas for improvement, and develop a roadmap for improving their digital capabilities. The model is particularly useful for organizations that want to understand how their digital capabilities compare to those of their peers and competitors, and to identify areas for investment and improvement. Figure 3 shows another maturity model for digital transformation, based on different dimensions of an organization that are impacted as the transformation progresses (Azhari et al. 2014). The authors depict eight dimensions of digitalization, namely strategy, leadership, products, operations, culture, people, governance, and technology. Organizations are assigned to one of five maturity levels, depending on the extent to which the dimensions are met. Companies classified as unaware are those with little or no digital capability. They lack awareness of the need for digital transformation. Companies at a conceptual level are typically those that offer a few digital products but do not yet have a digital strategy. Those with a defined level of digitalization are companies that have already gained experience with pilot implementations and have partially formed a digital strategy. At the point where a clear digital strategy is developed, an organization is classified as integrated. Finally, a transformed company is one that has fully implemented the digital strategy into its operations and business processes.

Digital maturity of an organization (Azhari et al. 2014)

In the more specific context of the manufacturing sector, the term Industry 4.0 has been used to describe the digital transformation of manufacturing. Increasingly, research examines digital readiness in the context of Industry 4.0 to assess whether manufacturing firms have the necessary capabilities to undertake this transformation. The “Industry 4.0 Maturity Index” (2016), developed by the FIR Institute at RWTH Aachen University, illustrates a step-by-step approach to implementing Industry 4.0. The maturity model has already been validated in manufacturing companies. It integrates the entire value creation process within the company, including development, logistics, production, as well as service and sales. In each of these areas, a comprehensive analysis of the respective Industry 4.0 maturity level is carried out. The steps that move a company from Industry 3.0 to Industry 4.0 are based on its use of data and analytics to gain visibility into its manufacturing processes, transparency into what is happening and why, predictability of future states and events, and finally adaptability, i.e., the ability to generate data-driven prescriptions for future behavior.

Another maturity model in the context of Industry 4.0 is the “IMPLUS—Industry 4.0 Readiness” model (Lichtblau and Stich 2015). The authors distinguish six levels of readiness, ranging from “Level 0: Outsiders” to “Level 5: Top Performers.“ The authors developed a questionnaire as a tool to measure the structural characteristics of the companies, their knowledge about Industry 4.0, their motivations and obstacles during the Industry 4.0 journey. Furthermore, the companies are grouped into high-level categories as newcomers (level 0 and 1), learners (level 2), and leaders (level 3 and above). Newcomers consist of companies that have never initiated any projects, learners are companies that have initiated their first projects related to Industry 4.0, and leaders are companies that are compared to other advanced companies in their projects to implement Industry 4.0 initiatives. The dimensions of the questionnaire are: “smart factories,” “smart products,” “data-driven service,” “smart operations,” and “employees.” Using the model, company profiles and main barriers in the listed dimensions are identified, which serve as a basis for creating action plans for companies to improve their Industry 4.0 readiness (Lichtblau and Stich 2015).

Inspired by this stream of digital transformation research, future research could develop an organizational transformation maturity model to assess an organization’s current level of readiness and capability to undertake organizational transformation efforts, and to provide a roadmap for improving these capabilities. Such a model could be particularly useful for organizations seeking to understand how their transformation capabilities compare to those of their peers and competitors, and to identify areas for investment and improvement. The model would consist of different levels of maturity, each representing an increasingly advanced level of readiness and capability for organizational transformation. However, simply translating Westerman et al.’s or other digital maturity models into an organizational transformation setting is probably not enough. A more sophisticated approach would also take into account the goals of the transformation process, i.e., the realization of societal goals (e.g., sustainability goals), and the extent to which the transformation progress has enabled novel approaches to achieving these goals. In a further step, such a model could also enable an ex-ante simulation of potential transformation activities, predicting the impact of their successful implementation on these overall objectives. However, building such a model is a complex undertaking that requires a large interdisciplinary research consortium.

5 Conclusion

Organizational transformation can be a complex and challenging process, as it often involves significant changes to the way work is done and can have a major impact on employees, customers, and other stakeholders. While there is a large body of existing research, our review of selected literatures indicates a number of areas where more research could be fruitful. One important question for future research is how organizations can sustain transformational change over the long term. Many organizations initiate change programs that are successful in the short term, but fail to achieve sustained change over the long term and reach their initial higher ambitions (Moschko et al. 2023). It is important to understand the factors (and their antecedents) that contribute to successful long-term transformation, like leadership commitment, employee engagement, and alignment of organizational culture with the desired change.

Secondly, research is required how to effectively manage resistance to change. Resistance to change is a common phenomenon in organizations and can significantly impede the success of transformational initiatives (Antons and Piller 2015). Understanding the sources of resistance, as well as effective strategies for managing it, is critical for successful organizational transformation. Related to this issue is future research how to effectively measure the impact of organizational transformation in order to steer the change initiative, but also to measure the effectiveness of countermeasures against resistance to transform. Measuring the success of organizational transformation is challenging, and traditional metrics such as financial performance may not provide a complete picture of the impact of transformation on the organization. Future research should focus on developing more comprehensive measures of the impact of transformation on organizational culture, employee engagement, customer satisfaction, and other key performance indicators.

Another important question is how to effectively manage the human side of organizational change at the micro-level. Transformational change can be stressful for employees, leading to anxiety, uncertainty, and resistance. Future research should focus on identifying effective strategies for managing the human side of organizational change, including communication, training, and support for employees. Related to this is the question of how to effectively manage the cultural aspects of organizational change. Organizational culture is a critical factor in the success of transformational initiatives. Future research should focus on identifying effective strategies for managing the cultural aspects of organizational change, including leadership development, communication, and employee engagement.

Answering these and many other questions will provide management scholars and the audiences they address (academia, but especially corporate managers and stakeholders) with the insights needed to manage the complex process of organizational change and transformation. Given the need for organizations to master the current digital (AI) revolution alongside their mandatory sustainability transformation (and addressing all 17 of the United Nations’ social development goals), we believe that those organizations that strive and succeed will be those that have first acquired the skills and behaviors to master second-order change.

To conclude our chapter, we asked the institution that is perhaps most transforming our personal lives as academics these days, the ChatGPT Transformer Language Model (Bouschery et al. 2023), to list the top five success factors for organizational transformation. We'll end our chapter with its response—because we couldn't have summed it up better:

In summary, these are the top five success factors for organizational transformation:

-

Resistance to change: People are often resistant to change, especially if it involves significant disruptions to their work or lifestyle. Organizations may need to overcome this resistance by communicating the benefits of the transformation and helping employees understand how it will impact them.

-

Communication: Ensuring that all stakeholders are kept informed about the transformation and its progress is crucial. This can be particularly challenging in large organizations with multiple levels of management and employees working in different locations.

-

Managing the change process: Effective change management is key to ensuring that the transformation is successful. This includes identifying the steps needed to implement the changes, establishing a timeline for the transformation, and providing resources and support to those affected by the changes.

-

Maintaining momentum: It is important to keep the momentum going during the transformation process. This can be challenging, especially if there are setbacks or delays.

-

Measuring success: Establishing clear metrics for measuring the success of the transformation is important. This can help organizations determine whether they are achieving their goals and make necessary adjustments as needed.

References

Alford RR, Friedland R (1985) Powers of theory: capitalism, the state, and democracy. Cambridge University Press

Amit R, Schoemaker PJ (1993) Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strateg Manag J 14(1):33–46

Antons D, Piller F (2015) Opening the black box of “not invented here”: attitudes, decision biases, and behavioral consequences. Acad Manag Perspect 29(2):193–217

Appio FP, Frattini F, Petruzzelli AM, Neirotti P (2021) Digital transformation and innovation management: a synthesis of existing research and an agenda for future studies. J Prod Innov Manag 38(1):4–20

Armenakis AA, Bedeian AG (1999) Organizational change: a review of theory and research in the 1990s. J Manag 25(3):293–315

Azhari P, Faraby N, Rossmann A, Steimel B, Wichmann K (2014) Digital transformation report 2014. Neuland, Köln

Bass BM (1985) Leadership: good, better, best. Organ Dyn 13(3):26–40

Bass BM, Avolio BJ, Jung DI, Berson Y (2003) Predicting unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional leadership. J Appl Psychol 88(2):207–218

Beer M, Walton AE (1987) Organizational change and development. Annu Rev Psychol 38:339–367

Beer M, Eisenstat RA, Spector B (1990) Why change programs don’t produce change. Harv Bus Rev 68(6):158–166

Berman S, Marshall A (2014) The next digital transformation: from an individual-centered to an everyone-to-everyone economy. Strategy Leadership 42(5):9–17

Berson Y, Avolio BJ (2004) Transformational leadership and the dissemination of organizational goals: a case study of a telecommunication firm. Leadersh Quart 15(5):625–646

Besson P, Rowe F (2012) Strategizing information systems-enabled organizational transformation: a transdisciplinary review and new directions. J Strateg Inf Syst 21(2):103–124

Bharadwaj A, El Sawy OA, Pavlou PA, Venkatraman NV (2013) Digital business strategy: toward a next generation of insights. MIS Q:471–482

Bititci US (2015) Managing business performance: the science and the art. John Wiley and Sons

Blauth M, Mauer R, Brettel M (2014) Fostering creativity in new product development through entrepreneurial decision making. Creativ Inno Manage 23(4):495–509

Bommer WH, Rich GA, Rubin RS (2005) Changing attitudes about change: longitudinal effects of transformational leader behavior on employee cynicism about organizational change. J Organ Behav 26(7):733–753

Bouschery S, Blazevic V, Piller F (2023) Augmenting human innovation teams with artificial intelligence: exploring transformer-based language models. J Prod Innov Manag 40(2):139–153

Brenk S, Lüttgens D, Diener K, Piller F (2019) Learning from failures in business model innovation: solving decision-making logic conflicts through intrapreneurial effectuation. J Bus Econ 89(8):1097–1147

Brettel M, Mauer R, Engelen A, Küpper D (2012) Corporate effectuation: entrepreneurial action and its impact on R&D performance. J Bus Ventur 27(2):167–184

Carmine S, Smith WK (2020). Organizational paradox. In: Oxford bibliographies

Chandler GN, Jansen E (1992) The founder’s self-assessed competence and venture performance. J Bus Ventur 7(3):223–236

Cook SD, Yanow D (2011) Culture and organizational learning. J Manag Inq 20:362–379

Correani A, De Massis A, Frattini F, Petruzzelli AM, Natalicchio A (2020) Implementing a digital strategy: learning from the experience of three digital transformation projects. Calif Manage Rev 62(4):37–56

Coviello NE, Joseph RM (2012) Creating major innovations with customers: insights from small and young technology firms. J Mark 76(6):87–104

Deming DE (1982) Out of the Crisis. MIT Press, Cambridge

DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW (1983) The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organisational fields. Am Sociol Rev 48(2):147–160

Drnevich PL, Kriauciunas AP (2011) Clarifying the conditions and limits of the contributions of ordinary and dynamic capabilities to relative firm performance. Strateg Manag J 32(3):254–279

Dutton JE, Dukerich JM (1991) Keeping an eye on the mirror: image and identity in organizational adaptation. Acad Manag J 34(3):517–554

Eisenbach R, Watson K, Pillai R (1999) Transformational leadership in the context of organizational change. J Organ Chang Manag 12(2):80–89

Eisenhardt KM, Martin JA (2000) Dynamic capabilities: what are they? Strateg Manag J 21(10):1105–1121

Eisenhardt KM, Martin JA (2010) Rewiring: cross-business-unit collaborations in multibusiness organizations. Acad Manag J 53(2):265–301

Elmquist M, Fredberg T, Ollila S (2009) Exploring the field of open innovation. Eur J Innov Manag 12(3):326–345

Felfe J (2006) Transformationale und charismatische Führung: stand der Forschung und aktuelle Entwicklungen. Zeitschrift für Personalpsychologie 5(4):163–176

Felfe J, Tartler K, Liepmann D (2004) Advanced research in the field of transformational leadership. German J Human Res Manage 18(3):262–288

Fisher G (2012) Effectuation, causation, and bricolage: a behavioral comparison of emerging theories in entrepreneurship research. Entrep Theory Pract 36(5):1019–1051

Fox-Wolfgramm SJ, Boal KB, Hunt JG (1998) Organizational adaptation to institutional change: a comparative study of first-order change in prospector and defender banks. Adm Sci Q 43(1):87–126

Granovetter M (1985) Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness. Am J Sociol 91(3):481–510

Grant RM (1996) Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strateg Manag J 17(S2):109–122

Greenwood R, Hinings CR (1996) Understanding radical organizational change: bringing together the old and the new institutionalism. Acad Manag Rev 21:1022–1054

Gruber M (2023) An innovative journal during transformational times: embarking on the 23rd editorial term. Acad Manag J 66(1):1–8

Haffke I, Kalgovas BJ, Benlian A (2016) The role of the CIO and the CDO in an organization’s digital transformation. In: Proceedings of the thirty seventh international conference on information systems (ICIS), Dublin.

Hage JT (1999) Organizational innovation and organizational change. Ann Rev Sociol 25(1):597–622

Hahn T, Knight E (2021) The ontology of organizational paradox: a quantum approach. Acad Manag Rev 46(2):362–384

Hanelt A, Bohnsack R, Marz D, Antunes C (2021) A systematic review of the literature on digital transformation: insights and implications for strategy and organizational change. J Manage Stud 58(5):1159–1197

Hess T, Matt C, Benlian A, Wiesböck F (2016) Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy. MIS Q Exec 15(2):123–139

Hiatt JM (2006) ADKAR: a model for change in business, government and our community. Prosci Research, Loveland, CO

Higgs M, Rowland D (2008) Change leadership that works: the role of positive psychology. Organisations and People 15(2):12–20

Hinings B, Gegenhuber T, Greenwood R (2018) Digital innovation and transformation: an institutional perspective. Inf Organ 28(1):52–61

Ko G, Roberts DL, Perks H, Candi M (2021) Effectuation logic and early innovation success: the moderating effect of customer co-creation. Br J Manag 33(4):1757–1773